Abstract

Yeast have been extensively used to model aspects of protein folding diseases, yielding novel mechanistic insights and identifying promising candidate therapeutic targets. In particular, the neurodegenerative disorder Huntington disease (HD), which is caused by the abnormal expansion of a polyglutamine tract in the huntingtin (htt) protein, has been widely studied in yeast. This work has led to the identification of several promising therapeutic targets and compounds that have been validated in mammalian cells, Drosophila and rodent models of HD. Here we discuss the development of yeast models of mutant htt toxicity and misfolding, as well as the mechanistic insights gleaned from this simple model. The role of yeast prions in the toxicity/misfolding of mutant htt is also highlighted. Furthermore, we provide an overview of the application of HD yeast models in both genetic and chemical screens, and the fruitful results obtained from these approaches. Finally, we discuss the future of yeast in neurodegenerative research, in the context of HD and other diseases.

Key words: Huntington disease, yeast, neurodegeneration, genetic modifiers, prions

The single-celled eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae has long been involved with the technological advancement of mankind. Commonly known as baker's yeast, for millennia this organism has been employed for the requisite fermentation in the production of bread, wine, beer and other food products.1 Louis Pasteur first described the critical role of yeast in fermentation in 1860, and conclusively showed that living yeast cells are required for this process.2 Since this time, yeast have been used extensively in biological sciences to explore the fundamental properties of the cell, and have become a vital genetic weapon in the arsenal of modern day medical scientists. This review provides an overview of the development, characterization and utilization of yeast models of Huntington disease (HD). These simple models have provided striking insights into the mechanisms underlying cellular toxicity in this disease, and have also uncovered many promising candidate drug targets for HD, several of which have been validated in animal models and hold great therapeutic promise.

Huntington Disease

HD is a fatal, late onset autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by the expansion of a CAG repeat tract in the IT15 gene, which encodes an N-terminal polyglutamine (polyQ) stretch in the huntingtin (htt) protein.3 PolyQ expansion beyond a critical length causes htt to misfold and aggregate,4 and leads to cellular toxicity. Clinical features include motor symptoms such as chorea, psychiatric changes and cognitive decline.5 HD pathology is characterized by the presence of intranuclear htt inclusions and neuronal cell loss, with medium spiny neurons in the striatum being particularly vulnerable.6,7

Expansion of the IT15 CAG tract above 39 repeats is fully penetrant for HD, with intermediate repeat lengths of 36–39 being incompletely penetrant.8–10 Although the age of onset is inversely correlated to the length of the repeat tract it only accounts for ∼44–72% of the variation in age of onset observed in HD patients.11 Genetic factors are thought to account for ∼40% of the remaining variation in age of onset and several disease modifying alleles of genes have been identified, including HAP112 and PGC1-α.13

Although misfolding of mutant htt is required for toxicity it is still unclear which misfolded species is primarily responsible. Much current research suggests that toxicity is mediated by an aggregation intermediate, potentially oligomers, whose incorporation into large aggregates is protective.14,15 Mutant htt causes widespread cellular dysfunction resulting in a range of phenotypes including transcriptional dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, defects in vesicle trafficking and autophagy, and altered energy metabolism.16,17 Although loss of a functional wild-type htt allele likely contributes to HD, the primary cause of most disease phenotypes is thought to be a toxic gain of function caused by expansion of the polyQ tract.18

To help elucidate the mechanisms causing HD and aid in the development of effective therapeutic compounds a wide array of mammalian cell and rodent models have been developed.19–22 HD research has also been aided by modeling the disease in other model organisms including the zebrafish Danio rerio,23 Drosophila melanogaster24,25 and Caenorhabditis elegans.26 Below we discuss the development, application and utility of yeast models of HD.

Yeast as a Model Organism

The baker's yeast S. cerevisiae is one of the best characterized eukaryotes and has been extensively used to model higher organisms. Indeed, much of our fundamental knowledge of processes such as the cell cycle originated from studies in yeast.27 In particular, the powerful genetics and well-characterized genomics of yeast have greatly aided biologists in recent decades. S. cerevisiae was the first eukaryotic organism to have its genome completely sequenced.28 The yeast genome is ∼12 Mb in size and contains 6,607 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) on 16 chromosomes. Classical approaches and high throughput studies have provided a wealth of information on the vast majority of yeast ORFs, including protein localization, genetic and physical interactions, deletion and overexpression phenotypes, and expression profiles.29 This data is integrated into several robust databases—such as the Saccharomyces genome database (SGD)—which contain extensive data, arguably making the yeast genome the best annotated amongst eukaryotes.29 Sequence comparisons and classical genetic and biochemical approaches have shown that many of the major biological processes such as lipid, DNA, protein and energy metabolism are highly conserved between yeast and humans.30,31 Conservation is not restricted to the pathway level, as many mammalian genes are able to complement mutations in their yeast orthologs.32 This has been exploited to elucidate the function of mammalian genes without clear yeast orthologs via analysis of complementation phenotypes in large panels of yeast deletion strains.

Another advantage of yeast is that this model is relatively inexpensive to maintain, easy to culture, and has a fast generation time (∼1–2 h). Yeast are extremely tractable to genetic manipulation and an amazing array of molecular and genetic tools have been developed by the yeast community. Resources include collections of yeast strains containing individual gene deletions33 and constructs for the overexpression of the vast majority of predicted ORFs.34 The development of automated screening platforms has made performing high-throughput yeast screens using these collections extremely facile and rapid. The capability of yeast to be maintained as haploids or mated to form diploids, and the ability to easily analyse the four products of meiosis, also makes yeast an extremely powerful tool for genetic studies. For example, the ability to mate and sporulate yeast in a high-throughput manner has been exploited in synthetic lethal screens to create a global map of yeast genetic interactions.35

While there are many advantages to using yeast as a model organism it is important to acknowledge that there are some limitations. As yeast is a unicellular organism it is not possible to model cellular processes which involve complex interactions between multiple specialised cell types, such as inflammation and synaptic transmission. Studies in yeast can, however, elucidate the underlying causes of cellular dysfunction which contribute to defects in these processes. Another limitation is the absence of some specific cellular pathways and proteins involved in disease pathogenesis, as well as the evolution of pathways and proteins to fulfil different functions in the cell. However, while cellular functions such as neurotransmitter release are not found in yeast, many important aspects of these processes are highly conserved, such as endocytosis and vesicle trafficking. Studies have also shown many mammalian genes without a clear yeast ortholog are functional in yeast,32 including several disease-relevant proteins discussed below. Furthermore, when protein function has diverged, or to study the effect of mutations in human proteins, “humanized” yeast can be created by replacing endogenous genes with their mammalian ortholog.36 Thus, while yeast models provide an invaluable tool for the study of human disease, it is vital to validate findings in higher organisms.

Yeast Models of Disease

In the past two decades a number of human disorders have been successfully modeled in yeast, including several neurodegenerative diseases with a protein misfolding component (Table 1). Early work focused on the effect of disease causing mutations or gene deletions of the yeast orthologs of human genes such as mitochondrial metalloproteases37 and frataxin.38 In recent years, many human disease-causing proteins without yeast orthologs have been successfully expressed in yeast, generating novel yeast models of disease.39–46 Indeed, the lack of an ortholog can be beneficial as it allows one to ascertain whether mutations cause a toxic gain of function or a decrease in wild-type cellular functions. In diseases where both scenarios are complicit, it allows the determination of the relative contribution of the two mechanisms to toxicity.

Table 1.

Yeast models of neurodegenerative disease

| Disease | Protein | Yeast Ortholog | References |

| Huntington disease | Huntingtin | No | This review |

| Parkinson disease | α-synuclein | No | 45, 110 |

| LRRK2 | No | ||

| Alzheimer disease | APP | No | 111 |

| Tau | No | ||

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Sod1 | Yes | 39, 41, 42, 46, 112–114 |

| Tardbp | No | ||

| Fus | No | ||

| Frontotemporal lateral sclerosis | Tardbp | No | 39–42, 46 |

| Fus | No | ||

| Prion disorders | Prp | No | 115, 116 |

| Friedrich's ataxia | Frataxin | Yes | 38, 117 |

| Niemann-Pick disease | NPC1 | Yes | 118 |

| Batten disease | CLN3 | Yes | 119 |

| PPT1 | Yes | ||

| Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia | AAA-proteases | Yes | 37, 120 |

Importantly, many yeast models faithfully recapitulate disease relevant phenotypes, with several key findings in yeast having been successfully validated in mammalian models and patients.47,48 They have provided valuable insights into disease relevant mechanisms of cellular toxicity and identified therapeutically viable strategies and compounds. Among the most extensively characterized yeast models of disease are those for HD and α-synucleipathies.47

Modeling HD in Yeast

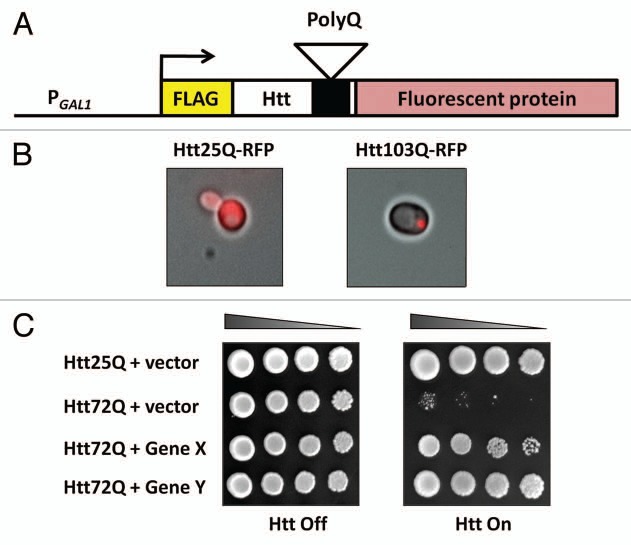

As the S. cerevisiae genome does not contain an ortholog of htt, HD has been modeled in yeast by expressing different portions of the human htt protein. The majority of yeast HD models express a short fragment of htt exon 1 encoding the first 17 amino acids followed by the polyQ tract (Fig. 1A).49 To prevent expansion and contraction of the polyQ tract the coding CAG repeats have been stabilised by the addition of interrupting CAA codons. Although these constructs only contain a small fraction of the htt protein, similar constructs are known to cause disease-relevant phenotypes in cultured cells and mice.19,50,51 Underscoring the relevance of htt fragment models, the expression of either a mutant htt exon 1 fragment or full length mutant htt results in similar phenotypes in mice, although disease progression is much faster and symptoms more severe in the fragment model.50

Figure 1.

A yeast model of Huntington disease. (A) The most widely-used yeast model of HD utilizes constructs containing the first 17 amino acids of htt, the polyQ tract, an N-terminal FLAG tag and a C-terminal fluorescent protein. To allow the routine culturing of strains expression is usually under the control of an inducible promoter, such as the galactose inducible GAL1 promoter. (B and C) Expression of a htt fragment with a polyQ tract within the normal size range (Htt25Q) leads to diffuse cytoplasmic distribution and no impairment of growth. In contrast a htt fragment containing a polyQ tract in the disease range (Htt103Q) forms large intracellular inclusions (both cytoplasmic and nuclear) and results in cellular toxicity, which can be suppressed by the co-expression of modifier genes (Gene X and Y).

Initial attempts to create yeast models of HD recapitulated the polyQ-dependent aggregation of htt but failed to reproduce the toxicity observed in mammalian systems.52–54 These early models were used to study htt aggregation and showed that overexpression of several yeast chaperones reduced mutant htt aggregation and increased the proportion of soluble htt.53,54 Interestingly, in some cases members of the same class of chaperones can have opposite effects, with increased levels of the Hsp40 chaperone Sis1 reducing aggregation and toxicity, while Ydj1 exacerbates toxicity and increases aggregate size when overexpressed.55 The strongest chaperone dependent effect was observed upon deletion of HSP104, which completely abolished mutant htt aggregation.53 The first yeast HD model to show cellular toxicity was created by Meriin et al. who expressed an amino-terminal FLAG-tagged construct containing the first 17 amino acids of htt followed by the polyQ tract and green fluorescent protein (GFP).44 Importantly, htt aggregation and toxicity increased in a polyQ dependent manner (Fig. 1B and C). Intriguingly, toxicity was not only reduced in hsp104Δ and sis1Δ strains but was strongly dependent on the yeast Rnq1 protein being present in its insoluble prion conformation [RNQ+]. The relevance of these observations will be discussed later in the review.

Subsequent studies have shown that the toxicity of mutant htt is heavily influenced by sequence context, explaining the lack of toxicity in the early yeast HD models.56,57 A series of elegant experiments demonstrated that the endogenous htt proline-rich region adjacent to the polyQ tract prevents toxicity,56–58 possibly by targeting mutant htt to the aggresome.59 Mutant htt constructs containing the proline-rich region have been observed to form a single large aggregate which co-localizes with aggresome markers, in contrast to toxic constructs lacking the proline-rich region which form multiple small aggregates.59 Furthermore, chemical or genetic perturbation of aggresome formation unmasks toxicity.59 The incorporation of mutant htt into the aggresome requires a number of factors including the 14-3-3 protein Bmh1, which interacts with soluble mutant htt oligomers and targets them to the aggresome, and the ATPase Cdc48 and its interacting partners Ufd1 and Nlp4, which act downstream of Bmh1 in aggresome formation.

In addition to the removal of the proline-rich region a FLAG-tag is required to unmask toxicity.57 It is thought that the acidic nature of the FLAG tag may mimic sumoylation of htt,57 which is required for toxicity in mammalian models.60 Intriguingly the proline-rich region and FLAG tag are capable of influencing htt toxicity both in cis and trans.58 For example, coexpression of a non-toxic FLAG-tagged Htt25Q construct with a benign Htt103Q construct lacking a FLAG tag results in cellular toxicity. Interestingly, toxicity requires the presence of an otherwise protective proline-rich region in the Htt103Q constuct. The expression of Htt25Q constructs containing a proline-rich region also recruits Htt103Q lacking the proline-rich region to the aggresome, ameliorating toxcity.59 The influence of these sequences in cis and trans suggests that in addition to altered protein conformation protein-protein interactions are required for toxicity. Differences in the cellular distribution of these htt interacting proteins may also play a role in mediating the toxicity of mutant htt. When mutant htt is localized to the nucleus by the addition of a nuclear localisation signal (NLS) it forms insoluble aggregates much more slowly, significantly increasing its toxicity.52,61 This may be due to differences in the type and abundance of chaperones and other proteins between cellular compartments.

Expression of Htt103Q in yeast leads to widespread cellular dysfunction resulting in death with apoptotic markers,62 recapitulating many of the phenotypes observed in mammalian models and HD patients.16,17 It is important to note that as the yeast genome does not contain an ortholog of htt, all phenotypes observed are independent of wild-type function. Phenotypes observed in yeast include defects in vesicle transport caused by sequestration of essential components of the endocytic machinery.63 Endocytic defects precede changes in several other cellular pathways and occur prior to the inhibition of growth, suggesting that they are not the result of a general decrease in cellular function. Alterations in the actin cytoskeleton have also been observed in yeast models of HD62–66 and may be caused by defects in vesicle trafficking, which is important for its maintenance and integrity.67 Importantly the htt-mediated defects in vesicle transport in yeast are consistent with observations in cultured mammalian cells and neurons where they contribute to defects in synaptic dysfunction.68,69 Early defects in the microtubule and actin cytoskeleton network are also observed in HD model mice and may contribute to toxicity by disrupting the mitochondrial network.70

Transcriptional dysregulation is a well documented phenomenon in HD16 and approaches aimed at correction of gene expression changes via histone deacetylase inhibitors have shown promising results in Drosophila, cultured cell and mouse models of HD.71 Similar alterations in the expression of genes involved in a wide array of cellular processes are observed in yeast following expression of mutant htt.52,72,73 The dysregulated genes are enriched for targets of the yeast Rpd3 histone deacetylase and treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors or deletion of the gene encoding the Rpd3 regulatory subunit Ume1, suppresses mutant htt toxicity.52,72

Defects in the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) have been observed in cultured cells and mice expressing mutant htt.74–76 Protein degradation is selectively impaired in yeast models of HD, with an increase in ER stress due to defects in endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) being one of the earliest defects observed in cells.77 Impairment is caused by sequestration of the yeast ortholog of p97 (Cdc48) and other proteins that are essential for ERAD. Alterations in ERAD contribute to htt toxicity in yeast as increased expression of components of the ERAD pathway, or upregulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), improves growth. Similar defects in ERAD were observed in PC12 cells,77 suggesting that this pathway is disease relevant and its modulation may have therapeutic value.

Several defects in mitochondrial function have been reported in yeast models of HD including decreased respiration, reduced complex II and III activity, altered mitochondrial membrane composition, decreased mitochondrial protein synthesis, and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, in addition to alterations in mitochondrial morphology and distribution.62,65,66 Increasing mitochondrial biogenesis partially suppresses mutant htt toxicity indicating that mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to, but is not the sole cause of toxicity.65 The exact mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction are unclear, but mutant htt may play a direct role as it associates with yeast mitochondrial membranes.65 The most harmonious explanation is that several pathways contribute to dysfunction; for example alterations in the actin cytoskeleton can account for changes in mitochondrial distribution and morphology.62,63,65,66 Increased ROS production caused by defects in ERAD77 and alterations in the kynurenine pathway78 may also negatively impact on mitochondrial function. The importance of mitochondrial dysfunction in HD is well established in mammalian models of HD and patients.79,80 Defects in yeast are strikingly similar to those observed in mammalian models and patients where the interaction of mutant htt with mitochondria causes widespread dysfunction, resulting in a cellular energy deficit that contributes to cell death.

Thus, detailed analyses of yeast HD models have shown that mutant htt causes widespread cellular dysfunction, including defects in transcriptional regulation, cell cycle, protein folding/homeostasis, vesicle trafficking and mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in apoptotic cell death.44,52,62,63,66,72,73,77,78,81 Yeast models therefore recapitulate many of the phenotypes observed in patients and mammalian models of HD,16,17 suggesting that the mode of toxicity is conserved between species and findings in yeast are relevant to disease.

Polyglutamine Proteins in Yeast: The Prion Link

In common with their mammalian counterparts yeast prions are self propagating infectious proteins that are inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion.82 A number of proteins capable of behaving as prions have been identified in yeast, with the best characterized being Sup35 [PSI+], Rnq1 [RNQ+] and Ure2 [URE3].82 Interestingly, the toxicity of mutant htt in yeast is dependent on cellular prion status.44 During the initial characterization of yeast models of HD it was noted that the deletion of genes encoding the chaperones Sis1 or Hsp104, as well as overexpression of Hsp104, altered the aggregation pattern of mutant htt and reduced toxicity.44,53 Both Hsp104 and Sis1 are required for the maintenance of yeast prions by mechanisms including the fragmentation of amyloidogenic prion aggregates into multiple small seeds, which act as templates for the conversion of newly synthesised proteins into their prion conformation.83–85 It was subsequently shown that in [rnq−] and [psi−] strains mutant htt is diffusely distributed and fails to produce robust cellular toxicity.44,55,57 A series of elegant experiments has shown that the effect of [RNQ+] and [PSI+] on mutant htt toxicity is additive, with an enhanced level of toxicity observed in [RNQ+] [PSI+] strains.55 Subsequent studies have confirmed that Hsp104 primarily suppresses mutant htt toxicity by altering prion formation, whereas the effect of excess Sis1 may be independent of prion status.55 It has been proposed that the observed prion dependent toxicity is due to the ability of amyloidogenic prions to act as a seed for the aggregation of htt.44 This is consistent with the observation that [RNQ+] and other prions act as templates for the conversion of proteins into their prion conformation.86,87 Conversely, mutant htt promotes the formation of [PSI+] and causes conformational changes in many glutamine (Q) and glutamine/asparagine-rich (Q/N-rich) proteins.86,88

Deletion of a number of putative yeast prions and Q-rich proteins has been found to reduce htt toxicity.58,78 Conversely a mild increase in the dosage of some Q-rich proteins, which causes many of them to aggregate, unmasks the toxicity of benign htt constructs in [RNQ+] cells.58 These proteins, including Rnq1, colocalize, and in many cases, co-purify with mutant htt aggregates. 58,61,63,89 This is consistent with the observation that many Q and Q/N-rich proteins interact and facilitate conformational changes in similar proteins.86,88 The association of Q and Q/N-rich proteins with htt aggregates has also been observed in mammalian systems, with sequestration of Q and Q/N-rich proteins into htt aggregates perturbing their normal biological function, potentially contributing to toxicity.90–92

The results of several studies investigating modulators of prion formation have implications for the interpretation of modifiers of mutant htt toxicity. A recent screen examined whether Rnq1-GFP was in the insoluble prion [RNQ+] or soluble [rnq−] form by monitoring formation of inclusion bodies in the 5,100 strains comprising the yeast genome deletion collection.93 A total of 58 strains were completely [rnq−], with an additional 83 containing a mixed population of [RNQ+] and [rnq−] cells. However, following introduction of constructs for the restoration of [RNQ+] status only hsp104Δ and rnq1Δ deletion strains were unable to propagate the prion, suggesting that prion loss in the majority of strains was due to chance and not as a result of the gene deletion. Though this study did not analyze aggregation of Rnq1 biochemically, it suggests that care should be taken to confirm that gene deletion strains which modulate mutant htt toxicity do so independently of [RNQ+] status (see below). Nonetheless, comparison of the above strains to known gene deletion suppressors of mutant htt toxicity finds that the majority of these suppressors do not function by directly altering [RNQ+] status78 (Clapp J and Giorgini F, unpublished data). It should also be noted that there appears to be some heterogeneity in [RNQ+] status between strain collections.73,78 Interestingly, the overexpression suppressors of mutant htt toxicity thus far characterized in yeast do not appear to modulate [RNQ+] status.73

Another link between prion formation and htt was recently revealed in a study showing that gene deletions which alter the induction of the prion form of Sup35 [PSI+] modulate mutant htt toxicity.94 Using a targeted genetic screen the authors identified two distinct classes of genes that modify [PSI+] induction. In class I mutants Sup35 formed characteristic ring structures, which are indicative of [PSI+] cells,95 while ring formation was inhibited in class II deletions. Interestingly, class I deletions (bem1Δ, bug1Δ, arf1Δ and hog1Δ) enhanced mutant htt toxicity and altered aggregation of the mutant protein. Mutant htt in class I deletions produced multiple small htt aggregates instead of the few large aggregates observed in wild-type cells. In class II deletions, by contrast, mutant htt was diffusely distributed and toxicity was reduced (las17Δ, vps5Δ and sac6Δ). The authors propose that class I genes prevent the effective transmission of [PSI+] to daughter cells and reduce the incorporation of toxic mutant htt intermediates into large cellular aggregates,94 which are generally thought to be protective.14,15 In contrast class II genes are important for the initial formation of the prion ring structures and misfolding of mutant htt into toxic species that are incorporated into large aggregates.94 The authors speculate that the formation of prions and protein misfolding may share several steps. The observation that many of the modifiers are involved in actin organization,94 and that drugs and mutations which alter actin organisation disrupt [PSI+] formation,96,97 further suggests that the formation and propagation of aggregated proteins is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton.

Genetic and Chemical Modifier Screens in HD Model Yeast

A distinct advantage of yeast is the ease with which genetic and chemical screens can be performed. The availability of constructs producing varying levels of toxicity has aided in these screens, allowing the identification of genes and compounds that suppress or enhance toxicity and/or aggregation. A non-toxic model was initially employed to identify 52 genes whose deletion enhanced mutant htt toxicity in a polyQ length dependent manner.98 The suppressors were enriched for proteins involved in ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism, protein folding and response to stress. A complementary gene deletion suppressor screen identified 28 genes involved in processes including vesicle transport, vacuolar degradation and transcription.78 Among the suppressors was bna4Δ, which encodes for kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), an enzyme in the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan degradation. KMO is essential for the production of the neurotoxic metabolites 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) and quinolinic acid (QUIN), levels of which were found to be elevated in the yeast model, paralleling observations in mammalian models and HD patients.99 In the bna4Δ strain 3-HK and QUIN were eliminated, and a mutant htt dependent increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) was abolished.78 Treatment with a chemical inhibitor produced similar protective results. The efficacy of inhibiting KMO has subsequently been validated by both genetic and chemical approaches in Drosophila and mouse models of HD.100,101

A number of screens have identified chemical compounds that modulate mutant htt toxicity and/or aggregation in yeast.102–104 Several promising therapeutic compounds have been identified, including the potent aggregation inhibitor C2-5, whose efficacy has been validated in mammalian cell, Drosophila and mouse models of HD.104,105 The efficacy of the aggregation inhibitor (−)-epigallocatechin (EGCG) was also validated in yeast following its identification in screens using purified htt protein, and was subsequently shown to be protective in Drosophila.103

Yeast genetic screens with HD models have thus provided valuable insights into the pathological mechanisms contributing to cellular dysfunction and death. Interestingly, there is very little overlap with genetic modifiers of Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or frontotemporal lobar degeneration identified using similar approaches,41,46,98,106–109 suggesting that the mechanism of toxicity is sequence specific and not simply the result of the accumulation of aggregated protein, a hallmark of all these diseases. This is further underscored by the observation that the majority of suppressors are not known to modulate protein misfolding.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Since their development, yeast models of HD have been extensively characterized and recapitulate many disease relevant phenotypes. Phenotypic analysis and genetic screens have highlighted the importance of cellular pathways including ERAD,77 endocytosis,63,77 mitochondrial dysfunction,62,65,66,101,105 and the kynurenine pathway72,78 in HD. Furthermore, screens employing yeast models of HD have also provided great therapeutic insight with the identification of promising therapeutic compounds such as KMO inhibitors,78 C2-5,104 and EGCG.103 Critically, the subsequent validation of genetic and chemical modifiers in Drosophila, mammalian cell and mouse models demonstrates the validity of using HD yeast models as a primary screening tool.63,77,101,105

The functional diversity of the genetic modifiers identified suggests that htt affects a broad range of cellular processes, with improvements in a single pathway being sufficient to reduce toxicity. Thus it is likely that modulating several pathways simultaneously may provide added protection, adding weight to the argument that combinational therapy may be beneficial for the treatment of HD. The successful validation of the above compounds and genes that modulate mutant htt toxicity in higher systems highlights the relevance and benefits of using yeast to model neurodegenerative diseases. The value of genetic modifiers of mutant htt toxicity identified in yeast is further supported by the observation that as much as ∼20% of variation in the age of disease onset in HD is determined by genetic factors. It is therefore of great interest to ascertain if human alleles of these genes modulate HD onset or progression.

A wealth of high throughput data has been generated in yeast models of HD including modifiers of toxicity63,77,78,98 and htt-mediated transcriptional changes.52,72 Integrating these kinds of data with similar screening data from other HD models will provide added insights into mechanisms of toxicity and may help identify potential therapeutic approaches. Indeed, functional integration of differentially expressed genes and genetic modifiers in yeast models of HD reveals a central role for protein translation and rRNA processing in disease.70 This integrative approach was also recently used in yeast models of α-synucleinopathy where analyses gave a global view of α-synuclein toxicity in yeast, showing transcriptional changes preferentially reveal metabolic changes, while genetic modifiers highlight regulatory changes.108 Thus the facile nature of both genetic and genomic approaches in yeast, combined with the power of modern bioinformatics approaches, will likely shed further light on HD. As these analyses are generated and cataloged, it will be critical to compare these observations with data obtained from similar efforts studying other protein misfolding diseases in yeast, which may ultimately provide insight into therapeutic approaches with general relevance for neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

F.G. acknowledges the Medical Research Council and the CHDI Foundation, Inc., for funding yeast research in our laboratory in the Department of Genetics, University of Leicester, UK. The authors thank Mariaelena Repici and Alexandra Woodacre for comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviation

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HD

Huntington disease

- 3-HK

3-hydroxykynurenine

- htt

huntingtin

- NLS

nuclear localisation signal

- ORF

open reading frame

- QUIN

quinolinic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

References

- 1.Sicard D, Legras JL. Bread, beer and wine: yeast domestication in the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex. C R Biol. 2011;334:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasteur L. Mémoire (memoire) sur le fermentation alcoolique. Annales de Chimie. 1860;58:323–426. (Fre). [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group, author. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Turmaine M, Mangiarini L, Hollenbach B, Hasenbank R, et al. Huntingtin-encoded polyglutamine expansions form amyloid-like protein aggregates in vitro and in vivo. Cell. 1997;90:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin JB, Gusella JF. Huntington's disease. Pathogenesis and management. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1267–1276. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611133152006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graveland GA, Williams RS, DiFiglia M. Evidence for degenerative and regenerative changes in neostriatal spiny neurons in Huntington's disease. Science. 1985;227:770–773. doi: 10.1126/science.3155875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, et al. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeil SM, Novelletto A, Srinidhi J, Barnes G, Kornbluth I, Altherr MR, et al. Reduced penetrance of the Huntington's disease mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:775–779. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quarrell OW, Rigby AS, Barron L, Crow Y, Dalton A, Dennis N, et al. Reduced penetrance alleles for Huntington's disease: a multi-centre direct observational study. J Med Genet. 2007;44:68. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langbehn DR, Brinkman RR, Falush D, Paulsen JS, Hayden MR. A new model for prediction of the age of onset and penetrance for Huntington's disease based on CAG length. Clin Genet. 2004;65:267–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wexler NS, Lorimer J, Porter J, Gomez F, Moskowitz C, Shackell E, et al. Venezuelan kindreds reveal that genetic and environmental factors modulate Huntington's disease age of onset. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3498–3503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308679101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzger S, Rong J, Nguyen HP, Cape A, Tomiuk J, Soehn AS, et al. Huntingtin-associated protein-1 is a modifier of the age-at-onset of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1137–1146. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weydt P, Soyal SM, Gellera C, Didonato S, Weidinger C, Oberkofler H, et al. The gene coding for PGC-1alpha modifies age at onset in Huntington's Disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatters DM. Protein misfolding inside cells: the case of huntingtin and Huntington's disease. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:724–728. doi: 10.1002/iub.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landles C, Bates GP. Huntingtin and the molecular pathogenesis of Huntington's disease. Fourth in molecular medicine review series. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:958–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross CA, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington's disease: from molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:83–98. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubinsztein DC. Lessons from animal models of Huntington's disease. Trends Genet. 2002;18:202–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apostol BL, Kazantsev A, Raffioni S, Illes K, Pallos J, Bodai L, et al. A cell-based assay for aggregation inhibitors as therapeutics of polyglutamine-repeat disease and validation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5950–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628045100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates GP, Gonitel R. Mouse models of triplet repeat diseases. Mol Biotechnol. 2006;32:147–158. doi: 10.1385/MB:32:2:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrante RJ. Mouse models of Huntington's disease and methodological considerations for therapeutic trials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:506–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trettel F, Rigamonti D, Hilditch-Maguire P, Wheeler VC, Sharp AH, Persichetti F, et al. Dominant phenotypes produced by the HD mutation in STHdh(Q111) striatal cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2799–2809. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xi Y, Noble S, Ekker M. Modeling neurodegeneration in zebrafish. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 11:274–282. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh JL, Pallos J, Thompson LM. Fly models of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:187–193. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambegaokar SS, Roy B, Jackson GR. Neurodegenerative models in Drosophila: polyglutamine disorders, Parkinson disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker JA, Connolly JB, Wellington C, Hayden M, Dausset J, Neri C. Expanded polyglutamines in Caenorhabditis elegans cause axonal abnormalities and severe dysfunction of PLM mechanosensory neurons without cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13318–13323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231476398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartwell LH, Culotti J, Reid B. Genetic control of the cell-division cycle in yeast. I. Detection of mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;66:352–359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.2.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, et al. Life with 6,000 genes. Science. 1996;274:546–563. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie KR, Hong EL, Cherry JM. Functional annotations for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome: the knowns and the known unknowns. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karathia H, Vilaprinyo E, Sorribas A, Alves R. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model organism: a comparative study. PLoS One. 2011;6:16015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petranovic D, Tyo K, Vemuri GN, Nielsen J. Prospects of yeast systems biology for human health: integrating lipid, protein and energy metabolism. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:1046–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang N, Osborn M, Gitsham P, Yen K, Miller JR, Oliver SG. Using yeast to place human genes in functional categories. Gene. 2003;303:121–129. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelperin DM, White MA, Wilkinson ML, Kon Y, Kung LA, Wise KJ, et al. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the yeast proteome with a movable ORF collection. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2816–2826. doi: 10.1101/gad.1362105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldred PM, Borts RH. Humanizing mismatch repair in yeast: towards effective identification of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer alleles. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1525–1528. doi: 10.1042/BST0351525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nolden M, Ehses S, Koppen M, Bernacchia A, Rugarli EI, Langer T. The m-AAA protease defective in hereditary spastic paraplegia controls ribosome assembly in mitochondria. Cell. 2005;123:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foury F, Cazzalini O. Deletion of the yeast homologue of the human gene associated with Friedreich's ataxia elicits iron accumulation in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1997;411:373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fushimi K, Long C, Jayaram N, Chen X, Li L, Wu JY. Expression of human FUS/TLS in yeast leads to protein aggregation and cytotoxicity, recapitulating key features of FUS proteinopathy. Protein Cell. 2011;2:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson BS, McCaffery JM, Lindquist S, Gitler AD. A yeast TDP-43 proteinopathy model: Exploring the molecular determinants of TDP-43 aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6439–6444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ju S, Tardiff DF, Han H, Divya K, Zhong Q, Maquat LE, et al. A yeast model of FUS/TLS-dependent cytotoxicity. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kryndushkin D, Wickner RB, Shewmaker F. FUS/TLS forms cytoplasmic aggregates, inhibits cell growth and interacts with TDP-43 in a yeast model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Protein Cell. 2011;2:223–236. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunst CB, Mezey E, Brownstein MJ, Patterson D. Mutations in SOD1 associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cause novel protein interactions. Nat Genet. 1997;15:91–94. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meriin AB, Zhang X, He X, Newnam GP, Chernoff YO, Sherman MY. Huntington toxicity in yeast model depends on polyglutamine aggregation mediated by a prion-like protein Rnq1. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:997–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Outeiro TF, Lindquist S. Yeast cells provide insight into alpha-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science. 2003;302:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.1090439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun Z, Diaz Z, Fang X, Hart MP, Chesi A, Shorter J, et al. Molecular determinants and genetic modifiers of aggregation and toxicity for the ALS disease protein FUS/TLS. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:1000614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braun RJ, Buttner S, Ring J, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Nervous yeast: modeling neurotoxic cell death. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winderickx J, Delay C, De Vos A, Klinger H, Pellens K, Vanhelmont T, et al. Protein folding diseases and neurodegeneration: lessons learned from yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1381–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duennwald ML. Monitoring polyglutamine toxicity in yeast. Methods. 2011;53:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodman B, Butler R, Landles C, Lupton MK, Tse J, Hockly E, et al. The Hdh(Q150/Q150) knock-in mouse model of HD and the R6/2 exon 1 model develop comparable and widespread molecular phenotypes. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Apostol BL, Illes K, Pallos J, Bodai L, Wu J, Strand A, et al. Mutant huntingtin alters MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 and striatal cells: ERK1/2 protects against mutant huntingtin-associated toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:273–285. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes RE, Lo RS, Davis C, Strand AD, Neal CL, Olson JM, et al. Altered transcription in yeast expressing expanded polyglutamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13201–13206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191498198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krobitsch S, Lindquist S. Aggregation of huntingtin in yeast varies with the length of the polyglutamine expansion and the expression of chaperone proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1589–1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muchowski PJ, Schaffar G, Sittler A, Wanker EE, Hayer-Hartl MK, Hartl FU. Hsp70 and hsp40 chaperones can inhibit self-assembly of polyglutamine proteins into amyloid-like fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7841–7846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140202897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gokhale KC, Newnam GP, Sherman MY, Chernoff YO. Modulation of prion-dependent polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity by chaperone proteins in the yeast model. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22809–22818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dehay B, Bertolotti A. Critical role of the proline-rich region in Huntingtin for aggregation and cytotoxicity in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35608–35615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. Flanking sequences profoundly alter polyglutamine toxicity in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11045–11050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604547103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Giorgini F, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. A network of protein interactions determines polyglutamine toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11051–11056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604548103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Meriin AB, Zaarur N, Romanova NV, Chernoff YO, Costello CE, et al. Abnormal proteins can form aggresome in yeast: aggresome-targeting signals and components of the machinery. FASEB J. 2009;23:451–463. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steffan JS, Agrawal N, Pallos J, Rockabrand E, Trotman LC, Slepko N, et al. SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington's disease pathology. Science. 2004;304:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1092194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Douglas PM, Summers DW, Ren HY, Cyr DM. Reciprocal efficiency of RNQ1 and polyglutamine detoxification in the cytosol and nucleus. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4162–4173. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sokolov S, Pozniakovsky A, Bocharova N, Knorre D, Severin F. Expression of an expanded polyglutamine domain in yeast causes death with apoptotic markers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meriin AB, Zhang X, Miliaras NB, Kazantsev A, Chernoff YO, McCaffery JM, et al. Aggregation of expanded polyglutamine domain in yeast leads to defects in endocytosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7554–7565. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7554-7565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muchowski PJ, Ning K, D'Souza-Schorey C, Fields S. Requirement of an intact microtubule cytoskeleton for aggregation and inclusion body formation by a mutant huntingtin fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:727–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022628699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ocampo A, Zambrano A, Barrientos A. Suppression of polyglutamine-induced cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by enhancement of mitochondrial biogenesis. FASEB J. 2010;24:1431–1441. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-148601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Solans A, Zambrano A, Rodriguez M, Barrientos A. Cytotoxicity of a mutant huntingtin fragment in yeast involves early alterations in mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes II and III. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3063–3081. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Engqvist-Goldstein AE, Drubin DG. Actin assembly and endocytosis: from yeast to mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:287–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.093127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qin ZH, Wang Y, Sapp E, Cuiffo B, Wanker E, Hayden MR, et al. Huntingtin bodies sequester vesicle-associated proteins by a polyproline-dependent interaction. J Neurosci. 2004;24:269–281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1409-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truant R, Atwal R, Burtnik A. Hypothesis: Huntingtin may function in membrane association and vesicular trafficking. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:912–917. doi: 10.1139/o06-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trushina E, Dyer RB, Badger JD, 2nd, Ure D, Eide L, Tran DD, et al. Mutant huntingtin impairs axonal trafficking in mammalian neurons in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8195–8209. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8195-8209.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gray SG. Targeting histone deacetylases for the treatment of Huntington's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16:348–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Giorgini F, Moller T, Kwan W, Zwilling D, Wacker JL, Hong S, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition modulates kynurenine pathway activation in yeast, microglia and mice expressing a mutant huntingtin fragment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7390–7400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tauber E, Miller-Fleming L, Mason RP, Kwan W, Clapp J, Butler NJ, et al. Functional gene expression profiling in yeast implicates translational dysfunction in mutant huntingtin toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:410–419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.101527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science. 2001;292:1552–1555. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bennett EJ, Shaler TA, Woodman B, Ryu KY, Zaitseva TS, Becker CH, et al. Global changes to the ubiquitin system in Huntington's disease. Nature. 2007;448:704–708. doi: 10.1038/nature06022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holmberg CI, Staniszewski KE, Mensah KN, Matouschek A, Morimoto RI. Inefficient degradation of truncated polyglutamine proteins by the proteasome. EMBO J. 2004;23:4307–4318. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duennwald ML, Lindquist S. Impaired ERAD and ER stress are early and specific events in polyglutamine toxicity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3308–3319. doi: 10.1101/gad.1673408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giorgini F, Guidetti P, Nguyen Q, Bennett SC, Muchowski PJ. A genomic screen in yeast implicates kynurenine 3-monooxygenase as a therapeutic target for Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2005;37:526–531. doi: 10.1038/ng1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bossy-Wetzel E, Petrilli A, Knott AB. Mutant huntingtin and mitochondrial dysfunction. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oliveira JM. Nature and cause of mitochondrial dysfunction in Huntington's disease: focusing on huntingtin and the striatum. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bocharova NA, Sokolov SS, Knorre DA, Skulachev VP, Severin FF. Unexpected link between anaphase promoting complex and the toxicity of expanded polyglutamines expressed in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3943–3946. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Shewmaker F, Nakayashiki T, Engel A, McCann L, et al. Yeast prions: evolution of the prion concept. Prion. 2007;1:94–100. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.2.4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aron R, Higurashi T, Sahi C, Craig EA. J-protein co-chaperone Sis1 required for generation of [RNQ+] seeds necessary for prion propagation. EMBO J. 2007;26:3794–3803. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Douglas PM, Treusch S, Ren HY, Halfmann R, Duennwald ML, Lindquist S, et al. Chaperone-dependent amyloid assembly protects cells from prion toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7206–7211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802593105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tipton KA, Verges KJ, Weissman JS. In vivo monitoring of the prion replication cycle reveals a critical role for Sis1 in delivering substrates to Hsp104. Mol Cell. 2008;32:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Derkatch IL, Uptain SM, Outeiro TF, Krishnan R, Lindquist SL, Liebman SW. Effects of Q/N-rich, polyQ and non-polyQ amyloids on the de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion in yeast and aggregation of Sup35 in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12934–12939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404968101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN(+)] Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Urakov VN, Vishnevskaya AB, Alexandrov IM, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Interdependence of amyloid formation in yeast: implications for polyglutamine disorders and biological functions. Prion. 4:45–52. doi: 10.4161/pri.4.1.11074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Y, Meriin AB, Costello CE, Sherman MY. Characterization of proteins associated with polyglutamine aggregates: a novel approach towards isolation of aggregates from protein conformation disorders. Prion. 2007;1:128–135. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.2.4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Furukawa Y, Kaneko K, Matsumoto G, Kurosawa M, Nukina N. Cross-seeding fibrillation of Q/N-rich proteins offers new pathomechanism of polyglutamine diseases. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5153–5162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0783-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nucifora FC, Jr, Sasaki M, Peters MF, Huang H, Cooper JK, Yamada M, et al. Interference by huntingtin and atrophin-1 with cbp-mediated transcription leading to cellular toxicity. Science. 2001;291:2423–2428. doi: 10.1126/science.1056784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schaffar G, Breuer P, Boteva R, Behrends C, Tzvetkov N, Strippel N, et al. Cellular toxicity of polyglutamine expansion proteins: mechanism of transcription factor deactivation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Manogaran AL, Fajardo VM, Reid RJ, Rothstein R, Liebman SW. Most, but not all, yeast strains in the deletion library contain the [PIN(+)] prion. Yeast. 2010;27:159–166. doi: 10.1002/yea.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Manogaran AL, Hong JY, Hufana J, Tyedmers J, Lindquist S, Liebman SW. Prion formation and polyglutamine aggregation are controlled by two classes of genes. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:1001386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou P, Derkatch IL, Liebman SW. The relationship between visible intracellular aggregates that appear after overexpression of Sup35 and the yeast prion-like elements [PSI(+)] and [PIN(+)] Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:37–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bailleul-Winslett PA, Newnam GP, Wegrzyn RD, Chernoff YO. An antiprion effect of the anticytoskeletal drug latrunculin A in yeast. Gene Expr. 2000;9:145–156. doi: 10.3727/000000001783992650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ganusova EE, Ozolins LN, Bhagat S, Newnam GP, Wegrzyn RD, Sherman MY, et al. Modulation of prion formation, aggregation and toxicity by the actin cytoskeleton in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:617–629. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.617-629.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Willingham S, Outeiro TF, DeVit MJ, Lindquist SL, Muchowski PJ. Yeast genes that enhance the toxicity of a mutant huntingtin fragment or alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;302:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.1090389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Thevandavakkam MA, Schwarcz R, Muchowski PJ, Giorgini F. Targeting kynurenine-3-monooxygenase (KMO): implications for therapy in Huntington's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:791–800. doi: 10.2174/187152710793237430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Campesan S, Green EW, Breda C, Sathyasaikumar KV, Muchowski PJ, Schwarcz R, et al. The Kynurenine Pathway Modulates Neurodegeneration in a Drosophila Model of Huntington's Disease. Curr Biol. 2011;21:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zwilling D, Huang SY, Sathyasaikumar KV, Notarangelo FM, Guidetti P, Wu HQ, et al. Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase inhibition in blood ameliorates neurodegeneration. Cell. 2011;145:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bodner RA, Outeiro TF, Altmann S, Maxwell MM, Cho SH, Hyman BT, et al. Pharmacological promotion of inclusion formation: a therapeutic approach for Huntington's and Parkinson's diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4246–4251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511256103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ehrnhoefer DE, Duennwald M, Markovic P, Wacker JL, Engemann S, Roark M, et al. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity in Huntington's disease models. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2743–2751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang X, Smith DL, Meriin AB, Engemann S, Russel DE, Roark M, et al. A potent small molecule inhibits polyglutamine aggregation in Huntington's disease neurons and suppresses neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:892–897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408936102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chopra V, Fox JH, Lieberman G, Dorsey K, Matson W, Waldmeier P, et al. A small-molecule therapeutic lead for Huntington's disease: preclinical pharmacology and efficacy of C2-8 in the R6/2 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16685–16689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707842104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, et al. Alpha-synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science. 2006;313:324–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1129462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liang J, Clark-Dixon C, Wang S, Flower TR, Williams-Hart T, Zweig R, et al. Novel suppressors of alpha-synuclein toxicity identified using yeast. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3784–3795. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yeger-Lotem E, Riva L, Su LJ, Gitler AD, Cashikar AG, King OD, et al. Bridging high-throughput genetic and transcriptional data reveals cellular responses to alpha-synuclein toxicity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:316–323. doi: 10.1038/ng.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zabrocki P, Bastiaens I, Delay C, Bammens T, Ghillebert R, Pellens K, et al. Phosphorylation, lipid raft interaction and traffic of alpha-synuclein in a yeast model for Parkinson. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1767–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xiong Y, Coombes CE, Kilaru A, Li X, Gitler AD, Bowers WJ, et al. GTPase activity plays a key role in the pathobiology of LRRK2. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1000902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bharadwaj P, Martins R, Macreadie I. Yeast as a model for studying Alzheimer's disease. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010;10:961–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gunther MR, Vangilder R, Fang J, Beattie DS. Expression of a familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutant human superoxide dismutase in yeast leads to decreased mitochondrial electron transport. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;431:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Johnson BS, Snead D, Lee JJ, McCaffery JM, Shorter J, Gitler AD. TDP-43 is intrinsically aggregation-prone and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations accelerate aggregation and increase toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20329–20339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nishida CR, Gralla EB, Valentine JS. Characterization of three yeast copper-zinc superoxide dismutase mutants analogous to those coded for in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9906–9910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chernoff YO. Stress and prions: lessons from the yeast model. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3695–3701. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Knight SA, Kim R, Pain D, Dancis A. The yeast connection to Friedreich ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:365–371. doi: 10.1086/302270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Berger AC, Hanson PK, Wylie Nichols J, Corbett AH. A yeast model system for functional analysis of the Niemann-Pick type C protein 1 homolog, Ncr1p. Traffic. 2005;6:907–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Phillips SN, Muzaffar N, Codlin S, Korey CA, Taschner PE, de Voer G, et al. Characterizing pathogenic processes in Batten disease: use of small eukaryotic model systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:906–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pearce DA. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: mitochondrial metalloproteases of yeast. Hum Genet. 1999;104:443–448. doi: 10.1007/s004390050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]