Abstract

Background

Prior studies show that men are more likely than women to defer essential care. Enrollment in high-deductible health plans (HDHP) could exacerbate this tendency, but sex-specific responses to HDHPs have not been assessed. We measured the impact of an HDHP separately for men and women.

Methods

Controlled longitudinal difference-in-differences analysis of low, intermediate, and high severity emergency department visits and hospitalizations among 6,007 men and 6,530 women for 1 year before and up to 2 years after their employers mandated a switch from a traditional health maintenance organization (HMO) plan to an HDHP, compared with contemporaneous controls (18,433 men, 19,178 women) who remained in an HMO plan.

Results

In the year following transition to an HDHP, men substantially reduced emergency department visits at all severity levels relative to controls (changes in low, intermediate, and high severity visits of −21.5%, [−37.9 to −5.2], −21.6%, [−37.4 to −5.7], and −34.4%, [−62.1 to −6.7], respectively). Female HDHP members selectively reduced low severity emergency visits (−26.9%, [−40.8 to −13.0]) while preserving intermediate and high severity visits. Male HDHP members also experienced a 24.2% [−45.3 to −3.1] relative decline in hospitalizations in year 1, followed by a 30.1% [2.1 to 58.1] relative increase in hospitalizations between years 1 and 2.

Conclusions

Initial across-the-board reductions in ED and hospital care followed by increased hospitalizations imply that men may have foregone needed care following HDHP transition. Clinicians caring for patients with HDHPs should be aware of sex differences in response to benefit design.

Introduction

High deductible health plans (HDHPs) are the fastest-growing health insurance products in the U.S.1 HDHPs generally have lower premiums compared with traditional plans. These low premiums result from many services being subject to high annual deductibles, which are generally paid by members out-of-pocket.2 HDHP membership tripled between 2006 and 2012,1–3 and 34% of workers now have health plans with deductibles of at least $1000.1,2 The Affordable Care act will likely accelerate both the availability and uptake of HDHPs through both employer-sponsored and exchange-based health insurance because of their greater up-front affordability, and disincentives in the Act for purchasing more generous (“Cadillac”) health plans.4 By charging patients directly for certain types of care, HDHPs are intended to reduce discretionary health care such as lower severity visits to the emergency department (ED), while simultaneously maintaining appropriate use such as preventive visits, screenings, and high acuity care.5 Previous research has found that ED utilization follows this pattern in the overall population,6–8 but it is not known whether these effects are the same among both men and women. Alongside growth in HDHP plans, ED utilization has also increased in recent years, with the largest increases among those who may face financial barriers to access.9

Prior research has not examined sex-specific impacts of high cost sharing but evidence suggests a need for such analyses. Although men generally have higher socioeconomic status than women, they are less likely to seek and receive needed health care.10–14 Sex differences in health care utilization are well documented; females use more preventive care and prescription medications than males.12,15,16 Women also use emergency care with greater frequency15 and resource intensity than men.16 These discrepancies in care patterns may be partially explained by sex differences in health care needs across the age spectrum, and sex-specific types health care services (reproductive health care, sex-specific cancers, etc.).14,15 But other factors are also at play. Behavioral and attitudinal differences (such as masculinity beliefs) also influence healthcare use and health seeking behaviors13,17–19 Because impacts of clinical and policy interventions may differ for males and females, the Institute of Medicine has recommended reporting sex-specific findings in clinical and translational research.20 Therefore, we investigated the impact of transition to an HDHP and changes in ED care and hospitalizations separately for men and women.

Methods

Setting

Harvard Pilgrim Health Care is a health insurance plan that covers approximately one million individuals in New England that began offering HDHPs in 2002. These HDHPs had individual deductibles ranging from $500–$2000 and family deductibles from $1000–$4000. Full coverage is available after exceeding the individual deductible or if the family’s combined expenses exceed the family deductible. ED and hospital care (and most other institution-based services) are subject to the deductible. After exceeding the deductible, members also have $100 copayments for ED visits, but these are waived if they are admitted to the hospital from the ED. The HDHP benefits structures analyzed here have been discussed in detail in prior studies,7,21,22 and are similar to those for HDHPs nationally.2 We estimate that fewer than 2% of the HDHP members studied had health reimbursement accounts, and none had health savings accounts. The traditional HMO members we studied faced copayments for in-network ED care (between $30–$100) and outpatient visits (between $5–$25). Inpatient copayments for HMO members ranged from $0 to $1000, with a median of $250.

Study Groups

HDHP Group

We identified Harvard Pilgrim members who were insured between April 2001 and February 2008 with at least one year of continuous traditional HMO enrollment followed by at least 6 months in the HDHP. We chose members whose Massachusetts-based employers offered only one health plan and who remained with the same employer for the entire period. Because their employers offered a single choice of plans and switched all employees to an HDHP, members in the HDHP group were unable to self-select their health plan. We identified an index date for each member (the date of the employer-mandated switch to an HDHP), a 12-month baseline period, and a 6- to 24-month follow-up period. Members with missing descriptive data or fewer than 6 months of follow up (N=130) were excluded from the analysis. After restricting our analysis to adults age 18–64, our final HDHP cohort included 12,537 members.

HMO Group

We identified Harvard Pilgrim members from Massachusetts employers enrolled in traditional HMO plans during the same 2001–2008 eligibility period and whose employers did not offer HDHPs, any other plan type, or non-Harvard Pilgrim plans, and we used 3:1 nearest neighbor propensity score matching methods (described in detail elsewhere) to construct an HMO control group of 37,611 contemporaneously-enrolled members age 18–64.8,21,23,24 The propensity score models used logistic regression to predict the likelihood of switching to an HDHP versus remaining in a traditional HMO based on age, sex, Adjusted Clinical Groups score, neighborhood education and poverty levels (from census-based geocoded data, below), family versus individual plan, index date, employer size, and baseline outpatient, ED, and hospital copayments. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using 2:1 and 1:1 matches. The HDHP and control groups had access to the same network of physicians and faced the same Harvard Pilgrim utilization controls.

ED Utilization

We identified ED visits from Harvard Pilgrim’s administrative claims database and used a validated7,25 modification of the Billings ED visit classification algorithm26 to categorize visits as low, intermediate, or high severity based on the probability that the diagnosis required ED-level care. Prior research has established that such visits are associated with corresponding low, intermediate, and high likelihood, respectively, of death25 or hospitalization.7 High severity visits were considered necessary care, and low severity visits were considered discretionary use of emergency care, consistent with previous studies.7,8 Among the men and women in our study population, the most common reasons for high severity ED visits were kidney stones, depressive disorders, and cardiac dysrhythmias/irregular heartbeat, and for intermediate severity visits, the most common reasons were chest pain, finger wounds, and abdominal pain. The most frequent reasons for low severity visits were headache, discomfort in legs, arms, elbows or knees, and sore throat.

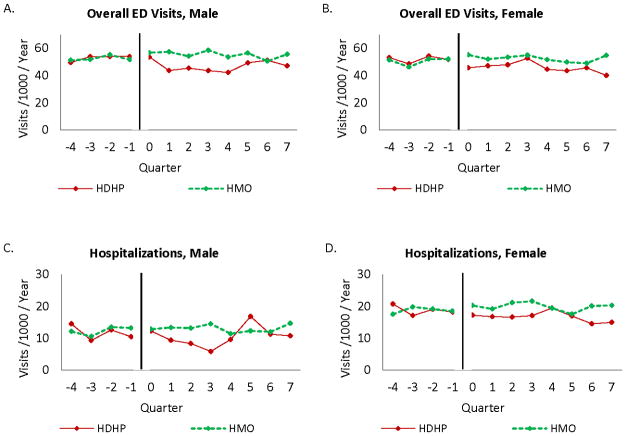

We summed ED visits on an annual basis for each member starting 1 year prior to the index date. Quarterly visit rates for the baseline and follow-up years, among men and women and calculated for both HDHP and HMO members, are presented in Figure 1. We calculated total annual ED expenditures, the sum of Harvard Pilgrim and member out-of-pocket expenditures as listed on claims.

Figure 1.

Quarterly rates of overall ED visits and hospitalizations for HDHP members and HDHP members and HMO controls for the year prior to and two years following transition to an HDHP, for males and females.

Hospital Utilization

We identified hospitalizations based on Harvard Pilgrim’s claims and summed annual hospitalizations per member. To exclude lower acuity day hospitalizations that often represent planned procedures (such as colonoscopy or arthroscopy), we included only admissions directly from the ED and overnight hospitalizations. We calculated total annual hospital expenditures using all claims during members’ hospitalization dates after excluding ED and outpatient claims. Both HDHP and control group members could have more than one ED visit or hospitalization accrue toward the total each year, and our methods adjust for within-person correlation using clustered standard errors (described below). Quarterly visit rates for HDHP members and HMO controls are shown for males and females in Figure 1.

Control Variables

Members’ sex (male or female) is based on enrollment data in Harvard Pilgrim’s administrative claims. To create measures of socioeconomic status, we linked members’ residential street addresses to their 2000 US Census block group and generated a socioeconomic status index based on neighborhood poverty and high school education levels. To estimate comorbidity, we applied the Adjusted Clinical Groups algorithm,27 to each member’s 12-month baseline period. The Adjusted Clinical Groups score is a validated methodology based on age, sex, and International Classification of Diseases, 9th-Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic codes derived from claims.28 Other covariates included age, employer size, and whether members were in individual or family plans.

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline characteristics of our study groups using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for bivariate comparisons. We used a difference-in-differences analysis with the individual member as the unit of analysis to examine whether changes in ED and hospital utilization during follow-up years 1 and 2 compared with baseline differed between HDHP members and HMO controls. We used Poisson regression to model the independent association between HDHP status and visit count and expenditure outcomes after controlling for age, employer size category, ACG score, and whether members were in individual or family plans.29 We included the index date in models to adjust for secular trends over time in healthcare utilization, and we adjusted for follow-up duration. All statistical models used generalized estimating equations to adjust for clustering of events within individuals between the baseline and follow-up years.30,31 We also created regression models that adjusted for employer-level clustering, and the results supported the main analysis, which accounts for clustering at the individual level. Models were stratified by patient sex and used interaction terms between study group and follow up years 1 and 2 to assess impacts of HDHP transition. Analyses were conducted using SAS Statistical Software, version 9.2.

The study was approved by the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care institutional review board and exempted from review by relevant boards at the University of Minnesota and the University of British Columbia.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The gender mix between the HDHP group and the control group was similar (HDHP group, 47.9% male; control group, 49.0% male), and characteristics of males and females were broadly similar across demographic, health insurance, clinical, and socioeconomic variables (Table 1). Among males, the HDHP and control groups had comparable rates of family plan participation (HDHP, 60.8%; control, 61.2%). However, the HDHP group was less likely to be insured through a small firm with fewer than 50 employees (71.6% vs. 79.4% p<0.001). Among females, HDHP members were less likely to participate in a family plan (HDHP, 57.4%; control, 61.3%; p<0.001) and less likely to be insured through a small firm compared with HMO controls. Socioeconomic status was similar for males and females, reflecting an upper-middle class population with over half of members living in neighborhoods with fewer than 5% of households living in poverty and approximately 3/4 living in neighborhoods where at least 85% of adults have a high school education. For both sexes, the members in the control group resided in neighborhoods with relatively higher levels of income and education, compared with the HDHP group (p<0.001 for neighborhood income and education levels, among both males and females).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for male and female members who switched to an HDHP, compared with an HMO control group

| Characteristic | Male Members | Female Members | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| HDHP Group | Control Group | P-value | HDHP Group | Control Group | P-value | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| n=6,007 | n=18,433 | n=6,530 | n=19,178 | |||||||

| In family plan - percent | 3652 (60.80) | 11285 (61.22) | 0.566 | 3747 (57.38) | 11746 (61.25) | <0.001 | ||||

| Small employer– no. (percent) | 4299 (71.57) | 14643 (79.44) | <.001 | 4475 (68.53) | 14901 (77.70) | <0.001 | ||||

| Diabetes - no. (percent) | 205 (3.41) | 543 (2.95) | 0.068 | 153 (2.34) | 351 (1.83) | 0.009 | ||||

| Asthma - no. (percent) | 82 (1.37) | 203 (1.10) | 0.098 | 126 (1.93) | 397 (2.07) | 0.487 | ||||

| Hypertension - no. (percent) | 486 (8.09) | 1352 (7.33) | 0.054 | 457 (7.00) | 1119 (5.83) | 0.007 | ||||

| Adjusted Clinical Groups Score - mean (SD) | 0.93 (1.58) | 0.98 (1.74) | 0.038 | 1.21 (1.57) | 1.31 (1.79) | 0.0491 | ||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Number (percent) living in neighborhoods with | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| < 5 percent below poverty | 3315 (55.19) | 10693 (58.01) | 3552 (54.40) | 11185 (58.32) | ||||||

| 5–9.9 percent below poverty | 1504 (25.04) | 4568 (24.78) | 1693 (25.93) | 4796 (25.01) | ||||||

| 10–19.9 percent below poverty | 889 (14.80) | 2270 (12.31) | 968 (14.82) | 2332 (12.16) | ||||||

| >=20 percent below poverty | 299 (4.98) | 902 (4.89) | 317 (4.85) | 865 (4.51) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Number (percent) living in neighborhoods with | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| <15 percent with < high school education | 4512 (75.11) | 14292 (77.53) | 5000 (76.57) | 14959 (78.00) | ||||||

| 15–24.9 percent with < high school education | 950 (15.81) | 2605 (14.13) | 980 (15.01) | 2730 (14.24) | ||||||

| 25–39.9 percent with < high school education | 392 (6.53) | 1160 (6.29) | 398 (6.09) | 1156 (6.03) | ||||||

| >=40 percent with < high school education | 153 (2.55) | 376 (2.04) | 152 (2.33) | 333 (1.74) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Emergency department copayment (percent) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| $25–$30 | 509 (8.47) | 1939 (10.53) | 468 (7.17) | 2071 (10.81) | ||||||

| $50 | 4516 (75.18) | 14648 (79.53) | 4887 (74.84) | 15077 (78.72) | ||||||

| $75–$100 | 982 (16.35) | 1831 (9.94) | 1175 (17.99) | 2004 (10.46) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean inpatient copayment - dollars (SD) | 304.44 (222.29) | 286.87 (231.59) | <0.001 | 278.20 (233.21) | 300.57 (220.99) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean annual expenses - dollars (SD) | 1590.53 (6170.91) | 1811.93 (8041.53) | 0.0507 | 25929.21 (9139.22) | 2166.29 (6113.73) | <.0001 | ||||

Notes: cell values are numbers and (percentages); except for ACG score and expenditures which are score/dollars (SD).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HDHP, high-deductible health plan; ED, emergency department

Utilization among male members who switched to an HDHP

Table 2 presents baseline levels of study outcomes and adjusted estimates of changes between baseline and follow up years 1 and 2 for HDHP members compared with matched HMO controls. Results are stratified by patient sex. At baseline, men who later transitioned to an HDHP averaged 211 emergency visits and 51 hospitalizations per 1000 members per year, while male HMO controls averaged 225 and 57, respectively. Difference-in-differences analysis (Table 2) demonstrated that male HDHP members decreased overall ED visits, from baseline through year 1 (−19.0% [−29.2 to −8.8]) and year 2 (−16.8% [−30.4 to −3.3]) when compared with controls. This decrease came via significantly decreased rates across all severity levels between baseline and the first follow-up year (low severity, −21.5% [−37.9 to −5.2], intermediate severity, 21.6%, [−37.4 to −5.7], and high severity −34.4% [−62.1 to −6.7], respectively). By the second follow up year, the relative reductions in emergency visits at each of the severity levels were no longer statistically significantly different than baseline levels. These results are also illustrated in Figure 1, panels A and C, which show unadjusted quarterly visit rates for ED care and hospitalization for male HDHP members compared with HMO controls, in the baseline and follow-up years.

Table 2.

Baseline levels and change from baseline to follow-up for emergency department and hospital visit rates and expenditures per year among male and female HDHP members and HMO control members.

| Baseline | Change From Baseline to Follow-up HDHP Group vs Controls, % (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to Year 1 | Baseline to Year 2 | |||

|

| ||||

| Male Members

| ||||

| HDHP Group n=6,007 |

Control Group n=18,433 |

|||

|

|

||||

| ED (No.) | 210.8 (1266) | 224.8 (4143) | −19.0% [−29.2%, −8.8%] | −16.8% [−30.4%, −3.3%] |

| Low Severity | 73.5 (442) | 82.4 (1518) | −21.5% [−37.9%, −5.2%] | −19.6% [−40.8%, 1.6%] |

| Intermediate | 86.0 (517) | 89.5 (1650) | −21.6% [−37.4%, −5.7%] | −9.6% [−29.7%, 10.5%] |

| High Severity | 27.0 (162) | 25.3 (467) | −34.4% [−62.1%, −6.7%] | −19.6% [−53.7%, 14.5%] |

| Hospital (No.) | 50.9 (306) | 57.3 (1057) | −24.2% [−45.3%, −3.1%] | 7.4% [−19.3%, 34.0%] |

| ED Expenditures (total $ in thousands) | 107.9 (647,865) | 107.8 (1,987,564) | −16.2% [−31.2%, −1.2%] | −7.6% [−26.7%, 11.5%] |

| Hospital Expenditures (total $ in thousands) | 920.3 (5,528,226) | 1076.4 (19,840,438) | −4.0% [−26.8%, 18.7%] | 6.0% [−25.0%, 36.9%] |

|

| ||||

| Female Members | ||||

|

| ||||

|

HDHP Group n=6,530 |

Control Group n=19,178 |

|||

|

|

||||

| ED (No.) | 206.7 (1350) | 228.1 (4375) | −10.9% [−20.2%, −1.5% | −12.8% [−26.7%, 1.2%] |

| Low Severity | 93.6 (611) | 96.4 (1848) | −26.9% [−40.8%, −13.0%] | −17.0% [−35.8%, 1.8%] |

| Intermediate | 71.2 (465) | 83.3 (1597) | 7.1% [−7.9%, 22.0%] | −8.6% [−30.7%, 13.5%] |

| High Severity | 18.1 (118) | 19.7 (377) | −3.2% [−30.7%, 24.3%] | −18.7% [−58.3%, 20.9%] |

| Hospital (No.) | 82.7 (540) | 93.3 (1790) | −18.2% [−33.7%, −2.6%] | −10.0% [−30.2%, 10.1%] |

| ED Expenditures (total $ in thousands) | 103.2 (673,995) | 111.6 (2,139,753) | −11.5% [−24.5%, 1.4%] | −21.2% [−40.4%, −2.1%] |

| Hospital Expenditures (total $ in thousands) | 1249.9 (8,161,607) | 1550.5 (29,735,324) | −7.8% [−23.4%, 7.8%] | −7.1% [−28.2%, 14.1%] |

Notes: Cell values are point estimates and (numbers) for HDHP and Control groups. Cell values are % changes and [95% confidence intervals] for changes between baseline and years 1 and 2.

Unadjusted rates measured in per 1000 per member per year for visits and dollars per member per year for expenditures. Adjusted differences in differences are from Poisson models with generalized estimating equations that included age, sex, employer category, index date, socioeconomic status, individual vs. family plan, and morbidity.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HDHP, high-deductible health plan; ED, emergency department.

ED expenditures also declined among HDHP males from baseline to year 1, compared to controls (−16.2% [−31.2 to −1.2]), but these expenditure reductions were not sustained through the second follow up year. In follow up year 1, total hospitalizations decreased dramatically among men who transitioned to an HDHP (−24.2% [−45.3 to −3.1]), compared with HMO controls. By year 2, the hospitalization rate had returned to baseline levels for male HDHP members. Between follow up years 1 and 2, hospitalizations of male HDHP members increased by 30.1% [2.1 to 58.1, p=0.0354, data not shown] compared with HMO controls. There were no measurable impacts of HDHP transition on hospital expenditures for men in either of the two follow up years.

Utilization among female members who switched to an HDHP

At baseline, HDHP females had 207 emergency visits (compared with 228 among controls) and 83 hospitalizations (compared with 93 among controls) per 1000 members per year. Between baseline and follow up year one, female HDHP members decreased their overall number of ED visits (−10.9% [−20.2 to −1.5]), compared with HMO controls. This decrease was not uniform across severity levels. In contrast to men, female HDHP members reduced low severity emergency visits (−26.9% [−40.8 to −13.0]) but maintained intermediate and high-severity visit rates. By the second follow-up year, utilization of emergency care was no longer statistically significantly different from baseline levels for female HDHP members, compared with HMO controls. However, ED expenditures decreased by 21.2% between baseline and follow-up year 2 (−40.4 to −2.1) among female HDHP members, compared with HMO controls. Female HDHP members also reduced hospitalizations in year 1 (−18.2%, [−33.7 to −2.6]), but this reduction was not sustained into the second year after transition to an HDHP. Patterns in ED visits and hospitalizations among women in the HDHP and control groups are also shown in Figure 1, panels B and D. Comparing women with men in Figure 1 highlights similar pre-treatment trends in HDHP and HMO groups for both men and women. The figure also shows sex-specific patterns of care in response to transition to a HDHP, with differences being particularly notable for and hospitalizations (C vs. D).

Discussion

Our results suggest that male and female members follow different health care utilization patterns after transition to an HDHP, with men’s response of an across-the-board reduction in emergency visit being of particular concern. Studies that do not separately analyze HDHP impacts by sex or ED visits by severity may mask important differences in how men and women respond to health plan benefit designs. These differences have important implications for clinicians who are increasingly caring for patients with high levels of cost sharing. They also have health and cost implications for employers, health plans, and beneficiaries themselves.

HDHPs aim to incentivize members to reduce inappropriate health care (e.g. utilizing the ED for low-severity visits) while maintaining appropriate use of preventive and necessary services.5 In our study, the HDHP appeared to act as a “blunt instrument” among men, reducing emergency visits across all severity levels as well as hospital care in the year following transition to an HDHP. This is a previously unknown effect of high-level cost sharing; past studies—that have not done sex-stratified analysis—have always detected selective reductions of lower severity ED visits in the overall population.7,8,32 The initial across-the-board reduction in care among men was followed by a year in which emergency care did not differ appreciably from baseline levels but hospitalizations increased by 30.1%, which is also illustrated in Figure 1, panel C. This substantial swing in hospital utilization (and ED utilization to a lesser degree) are consistent with the hypothesis that men who transition to HDHPs may forego needed care in the immediate term, resulting in delays or increased severity of illness when care is later sought and received. While hospital visits increased for male HDHP members between follow up years 1 and 2, there was no measurable impact on hospital expenditures, perhaps indicating less intensity of hospital care or shorter length of stay. It is important to note that some of the ED visit reductions experienced by male HDHP members, especially those for low-severity visits, may comprise a clinically appropriate and value-enhancing modification of health care utilization patterns. The most concerning aspect of men’s response patterns to HDHPs is that ED utilization was not differentially impacted by visit severity.

In contrast, women seemed to respond to the HDHP largely as intended, maintaining stable rates of intermediate and high severity care and limiting reductions in ED utilization to low severity visits. Utilization patterns in their second follow-up year might be more likely to represent a learning effect as opposed to a more predominant deferred care effect among men. The baseline visit rates and expenditures for males and females shown in Table 2 indicated that women had comparatively higher rates of low-severity emergency visits at baseline, which might have allowed for greater reduction of such care following transition to an HDHP. More frequent hospitalizations and greater hospital expenditures among women at baseline, compared with men (Table 2), likely reflect the role of maternity-related hospitalizations in driving higher utilization rates. The reduction in hospitalizations among female HDHP members compared with controls in follow up year 1 may reflect changes in childbirth-related plans following transition to an HDHP. Injury-related emergency care, including self-inflicted injury, is more frequently required and sought by men, compared with women, and is also associated with higher rates of hospitalization among men vs. women;33,34 however, childbirth is distinguished by the possibility of planning and prevention in way that high acuity injury care is not.

While no prior studies have focused on the impact of HDHP transition on males and females separately, extensive qualitative and exploratory research documents lower levels of health care utilization of among males and suggests that adult men’s health care avoidance is due in part to masculinity ideals that link “manhood” with a reluctance to ask for help; studies in population-based samples confirm that masculinity beliefs manifest in males exerting independence and self-reliance by not seeking needed care.13,18,35–37 Our findings suggest that the substantial financial barriers of HDHPs might exacerbate the tendency of men to delay or forego needed care, possibly leading to adverse health consequences. As such, clinicians may play an important mitigating role by cultivating professional awareness of how changes in health plans may impact utilization, especially for males. Health care providers may also use clinical encounters as an opportunity to emphasize the importance of seeking appropriate care and to discuss patient concerns regarding out of pocket costs.

These results are also important in a policy context. A primary aim of HDHPs is to slow the growth in health care costs and to reduce overall expenditures by exposing patients to some of the costs of care. Our analysis showed that transition to an HDHP has mixed results on producing cost savings via reduced expenditures, with evidence of potential cost savings by year 2 for ED visits among women but not among men or for hospital care; however, further research on financial impacts is needed. HDHPs are rapidly expanding, especially among employer-sponsored health insurance plans,1,2 and the Affordable Care Act may accelerate this growth.4 Starting in 2014, the plans most affordable to small employers and individuals in state-based exchanges (the “bronze plans,” with a 60% actuarial value) will likely be HDHPs,38 and our analysis indicates that male HDHP members may seek to reduce out-of-pocket spending by avoiding needed emergency care, resulting in potentially greater future health care needs rather than the cost savings that the HDHP is intended to promote. To address this, health plans, employers, or clinicians may want to develop educational interventions to inform HDHP patients about their benefit structures, the risks of avoiding needed care due to costs, and to identify HDHP members at high risk of delaying or foregoing necessary services. Employers that primarily hire men might want to carefully consider whether HDHPs are the optimal choice of coverage. Sex-specific strategies may be developed to account for the role of masculinity beliefs in contributing to the patterns of care uncovered in this analysis.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. The administrative data used in our analysis contain few direct measures of health and socioeconomic status. We selected a population whose employers mandated a switch to an HDHP, thus reducing the potential for selection bias on the part of the member; however, it is possible that employers may have chosen plans based on employee preferences, health status, or prior expenditures. Even so, there are limited threats to the internal validity of this study as any such factor would have to differentially impact HDHP male and female members, compared with male and female HMO controls, at the time of the transition to HDHP. Generalizability is limited by several factors including the specific deductibles of the plans we studied, which –while common during the time period of this study39 - are not as high as some current commercial plans and the focus on employer-based coverage as well as our focus on primarily small employers, though these represent the fastest growing segment of HDHP growth. The findings we uncovered may even be more pronounced in benefits plans or settings with a lesser focus on prevention. The potential generalizability is strengthened by the fact that the ED utilization rates in our study population (210.8 visits per 1000 members/year at baseline for male HDHP members and 206.7 for women in HDHP plans) are comparable to national estimates of 188.7 (95% CI [152.3–225.1]) among privately-insured U.S. adults in 2007.9

Conclusion

Men appeared to have a concerning response to a HDHP transition. Initial across-the-board reductions in ED and hospital care followed by increased hospitalizations might indicate that male HDHP members postponed needed care in the first follow-up year. Female HDHP members appeared to respond more appropriately, reducing low severity emergency visits and preserving high and intermediate severity visits in the first follow-up year. Although the U.S. health reform debate has appropriately highlighted challenges women face in receiving appropriate care,20,40 less attention has focused on how men will fare. As the health care environment undergoes substantial change in the coming years, it will be essential for policy research to separately evaluate effects on men and women. Absent such a lens, researchers, policymakers, and clinicians risk overlooking a surprisingly vulnerable group (insured males) that might benefit from novel and targeted interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgment: This work was supported by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant (K12HD055887) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute on Aging, at the National Institutes of Health, administered by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health (Dr. Kozhimannil, Ms. Blauer-Peterson) and by a Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation grant to Dr. Wharam. Dr. Law receives salary support through a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Career Investigator Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Drs. Wharam and Zhang receive salary support from the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

Contributor Information

Katy B. Kozhimannil, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Michael R. Law, Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Cori Blauer-Peterson, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Fang Zhang, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA

J. Frank Wharam, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, MA, USA

References

- 1.Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al. Health Benefits in 2012: Moderate premium increases for employer-sponsored plans; young adults gained coverage under ACA. Health Aff. 2012 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0708. doi:1-.1377/hlthaff.2012.0708 published online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Education Trust. Employee Health Benefits Survey 2012. Washington, DC: 2012. [Accessed December 13, 2012.]. Available at: http://ehbs.kff.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo H. January 2011 Census Shows 11.4 Million People Covered by Health Savings Account/High-Deductible Health Plans (HSA/HDHPs) Washington, DC: America’s Health Insurance Plans, Center for Policy and Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) [Accessed December 13, 2012.];State Health Insurance Mandates and the PPACA Essential Benefits Provisions. 2012 Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/issues-research/health/state-ins-mandates-and-aca-essential-benefits.aspx.

- 5.Herzlinger RE. Let’s put consumers in charge of health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2002;80(7):44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newhouse J. Consumer-directed health plans and the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Health Aff. 2004;23(6):107–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.6.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wharam J, Landon B, Galbraith A, Kleinman K, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1093–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wharam JF, Landon BE, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. High-Deductible Insurance: Two-Year Emergency Department and Hospital Use. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(10):e410–e418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA. 2010;304(6):664–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. Int J Men’s Health. 2003;2(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J Pub Health. 2003;93(5):724–31. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owens GM. Gender differences in health care expenditures, resource utilization, and quality of care. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(3 Suppl):2–6. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.S6-A.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer KW, Mouzon DM. “Macho Men” and Preventive Health Care Implications for Older Men in Different Social Classes. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):212–227. doi: 10.1177/0022146510393972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaidya V, Partha G, Karmakar M. Gender differences in utilization of preventive care services in the United States. J Womens Health. 2012;21(2):140–145. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinkhasov RM, Wong J, Kashanian J, et al. Are men shortchanged on health? Perspective on health care utilization and health risk behavior in men and women in the United States. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(4):475–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Family Pract. 2000;49(2):147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychol. 2003;58(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien R, Hunt K, Hart G. ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Soci Sci Med. 2005;61(3):503–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green CA, Pope CR. Gender, psychosocial factors and the use of medical services: a longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(10):1363–72. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Sex-Specific Reporting of Scientific Research - Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozhimannil KB, Huskamp HA, Graves AJ, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. High-deductible health plans and costs and utilization of maternity care. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):e17–e25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wharam J, Galbraith A, Kleinman K, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D, Landon B. Cancer screening before and after switching to a high-deductible health plan. Ann Int Med. 2008;148(9):647–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wharam JF, Graves AJ, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Landon BE. Two-year Trends in Cancer Screening Among Low Socioeconomic Status Women in an HMO-based High-deductible Health Plan. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27(9):1112–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2057-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wharam JF, Graves AJ, Landon BE, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Two-year trends in colorectal cancer screening after switch to a high-deductible health plan. Med Care. 2011;49(9):865–871. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b35d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballard DW, Price M, Fung V, et al. Validation of an algorithm for categorizing the severity of hospital emergency department visits. Med Care. 2010;48(1):58–63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd49ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Commonwealth Fund; 2000. Emergency department use in New York City: a substitute for primary care? [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Reference Manual, Version 7.0. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid RJ, Roos NP, MacWilliam L, Frohlich N, Black C. Assessing Population Health Care Need Using a Claims-based ACG Morbidity Measure: A Validation Analysis in the Province of Manitoba. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1345–1364. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation?: Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed M, Fung V, Brand R, et al. Care-seeking behavior in response to emergency department copayments. Med Care. 2005;43(8):810–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000170416.68260.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rost K, Hsieh Y-P, Xu S, Harman J. Gender Differences in Hospitalization After Emergency Room Visits for Depressive Symptoms. J Womens Health. 2011;20(5):719–724. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doshi A, Boudreaux ED, Wang N, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA. National study of US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1997–2001. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1385–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(6):616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calasanti T. Feminist gerontology and old men. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(6):S305–S314. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.s305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.What the Actuarial Values in the Affordable Care Act Mean. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. [Accessed on Deccember 13, 2012.]. Available at http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8177.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Employer Health Benefits: 2009 Annual Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Education Trust; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson KA. Women’s health and health reform: implications of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cur Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22(6):492–297. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283404e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.