Histone modification at the plant immune receptor gene modulates immune responses in Arabidopsis.

Abstract

Disease resistance (R) genes are key components in plant immunity. Here, we show that Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) E3 ubiquitin ligase genes HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION1 (HUB1) and HUB2 regulate the expression of R genes SUPPRESSOR OF npr1-1, CONSTITUTIVE1 (SNC1) and RESISTANCE TO PERONOSPORA PARASITICA4. An increase of SNC1 expression induces constitutive immune responses in the bonzai1 (bon1) mutant, and the loss of HUB1 or HUB2 function reduces SNC1 up-regulation and suppresses the bon1 autoimmune phenotypes. HUB1 and HUB2 mediate histone 2B (H2B) monoubiquitination directly at the SNC1 R gene locus to regulate its expression. In addition, SNC1 and HUB1 transcripts are moderately up-regulated by pathogen infection, and H2B monoubiquitination at SNC1 is enhanced by pathogen infection. Together, this study indicates that H2B monoubiquitination at the R gene locus regulates its expression and that this histone modification at the R gene locus has an impact on immune responses in plants.

Plants live in a changing environment, and they are often exposed to biotic stresses imposed by pathogens and herbivores. Resistance or tolerance to biotic stresses is conferred by preexisting physical and chemical barriers as well as inducible immune responses. Such immune responses involve reprogramming expression of a large number of genes (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Eulgem, 2005; Doehlemann et al., 2008). As an important regulatory mechanism for gene expression, chromatin remodeling is now revealed to play a role in plant immunity (March-Díaz et al., 2008; Dhawan et al., 2009; Berr et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2013).

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA is packaged in a highly organized nucleoprotein complex known as chromatin (Schneider and Grosschedl, 2007). Nucleosome, the basic subunit of chromatin, contains DNA of about 147 bp packed and wrapped around a core of eight histone molecules consisting of two copies of each of histone: H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Schneider and Grosschedl, 2007). Specific modifications of histones act like gene expression codes that direct or correlate with gene expression status (Heyse et al., 2009). For instance, histone methylation and ubiquitination can either activate or repress transcription depending on their targets. Trimethylations of H3 Lys-4 and H3 Lys-36 (H3K4me3 and H3K36me3) and monoubiquitination of H2B (H2Bub1) are enriched at actively expressed genes, whereas H3K27me3 is associated with repressed genes and H3K9me2 and H4K20me1 are enriched at heterochromatin and silenced transposon regions (Liu et al., 2007; Quan and Hartzog, 2010; Berke et al., 2012).

Histone modification plays an important role in maintaining and reprogramming gene expression that is critical for many essential developmental processes, such as flowering time control (Cao et al., 2008), cell wall development (Dhawan et al., 2009), root growth (Yao et al., 2013), and seed development (Liu et al., 2007). It is also involved in many plant defense responses (Zhou et al., 2005; Dhawan et al., 2009; Berr et al., 2010; Palma et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2013). Pathogen infection or chemicals mimicking pathogen infection induce histone acetylation and methylation changes at the promoter of defense-related genes, such as PR1, WRKY6, WRKY29, and WRKY53 (Jaskiewicz et al., 2011; De-La-Peña et al., 2012). Pathogens can manipulate histone modifications in host cells to facilitate their infection, supporting a role of these modifications in plant immunity (Anand et al., 2007; Terakura et al., 2007; Zurawski et al., 2009). Mutations in genes coding for histone modification enzymes have been found to alter disease resistance. For instance, an arabidopsis trithorax-related7(atxr7) mutant deficient of an H3K4 methylase is more susceptible to oomycete pathogens (Xia et al., 2013). An impairment in histone methyltransferase SET DOMAIN GROUP8 (SDG8) makes plants more susceptible to hemibiotrophic bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000) and necrotrophic fungi Alternaria brassicicola (Berr et al., 2010). The mutant of ATX1, a gene involved in H3K4 trimethylation, is defective in the induction of WRKY70, a transcription factor in the salicylic acid (SA)-mediated defense against bacterial pathogens (Alvarez-Venegas and Avramova, 2005; Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2007). Overexpression of a histone deacetylase gene, HDA19, in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) induces ethylene- and jasmonate acid-regulated PR genes expression and results in increased resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogen A. brassicicola (Choi et al., 2012). In addition, mutants lacking subunits of the SWI/SNF-RELATED1 complex that installs histone variant H2A.Z have reduced SA-mediated defense responses, indicating a role of histone variant placement in plant immunity (March-Díaz et al., 2008). Histone modification is also implicated in mediating autoimmune responses. For instance, the expression of a nucleotide-binding Leu-rich repeat (NB-LRR) type of resistance (R) gene, LAZ5, requires trimethylation of H3K36 by SDG8 (Palma et al., 2010), and an H3K4 methyltransferase ATXR7 is required for the expression of two NB-LRR resistance genes: SUPPRESSOR OF npr1-1, CONSTITUTIVE1 (SNC1) and RESISTANCE TO PERONOSPORA PARASITICA 4 (RPP4; Xia et al., 2013).

H2Bub1 is implicated in transcription activation and required for the methylation of H3K4 and H3K36 in yeasts (Dover et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2007). The conversion of H2B to H2Bub1 is carried out by two E3 ubiquitin ligases in Arabidopsis: HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION1 (HUB1) and HUB2 (Liu et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2008). HUB1 and HUB2 work in the same genetic pathway to control flowering time by enhancing expression of FLOWERING LOCUS C(FLC) and its homologs (Cao et al., 2008; Van Lijsebettens and Grasser, 2010). HUB1 promotes cell cycle progression from G2 phase into M phase (Fleury et al., 2007) and regulates expression of dormancy-related (Liu et al., 2007) and circadian-controlled genes (Himanen et al., 2012). In addition to its critical role in development, HUB1 was recently shown to be required for resistance to the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea (Dhawan et al., 2009). These results indicate that H2Bub1 plays important roles in plant stress responses.

R genes, as central players of plant immunity, are tightly regulated for effective defense responses and a balance between defense activation and plant growth (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Hua, 2013). The importance of repressing R genes under nonpathogenic conditions is readily revealed by the dwarf phenotypes in autoimmune mutants where R genes are constitutively activated (Gou and Hua, 2012). BONZA1 (BON1) is an evolutionarily conserved copine gene, and it is a negative regulator of an NB-LRR–encoding R gene SNC1 and other R-like genes (Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006). The loss-of-function (l-o-f) mutant bon1-1 (referred to as bon1) has enhanced disease resistance and as a consequence, a dwarf phenotype (Hua et al., 2001; Jambunathan et al., 2001). The up-regulation of the R gene SNC1 in bon1 provides a good system to study R gene transcriptional regulation and immune response regulation. To reveal molecular mechanisms underlying the induction of autoimmune responses in the bon1 mutant, we carried out a genetic screen for suppressors of bon1 and identified one suppressor gene SBO3 as MODIFIER OF snc1, 1 (MOS1; Z. Bao and J. Hua, unpublished data). MOS1 encodes a HLA-B ASSOCIATED TRANSCRIPT2 domain-containing protein and is required for the autoimmunity phenotypes in the gain-of-function mutant snc1-1 (referred to as snc1; Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2010b). Here, we find that HUB1, an MOS1 coexpressed gene, is required for autoimmune responses in bon1. It confers H2B monoubiquitination at the SNC1 region to up-regulate SNC1 in the bon1 mutant as well as on pathogen infection. Thus, histone modification directly at the R gene SNC1 locus modulates its gene expression and impacts plant immune responses.

RESULTS

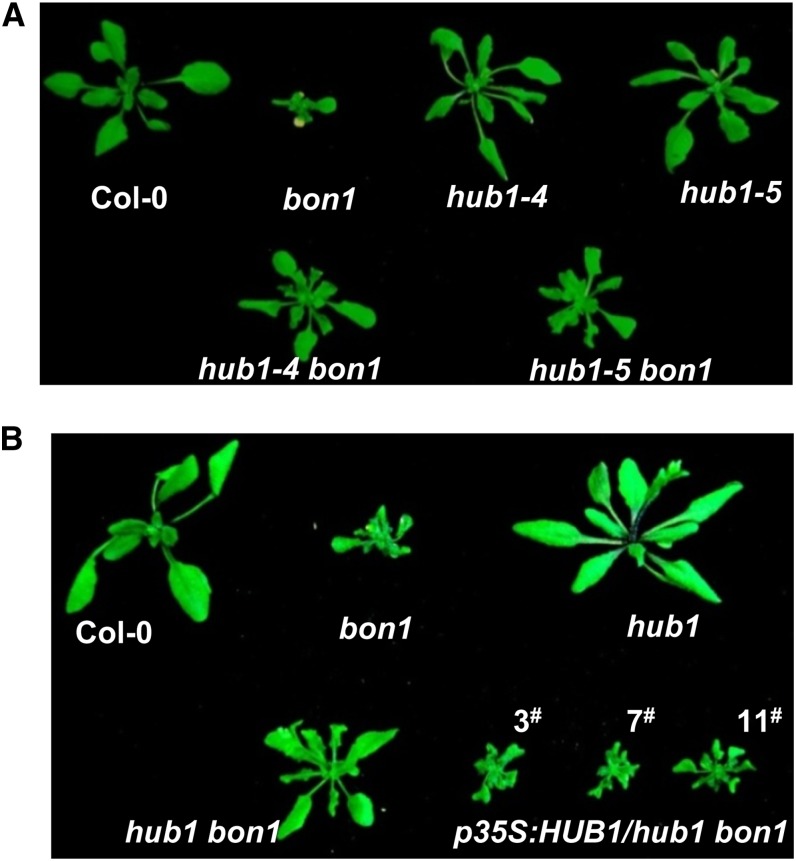

Loss of HUB1 Function Partially Suppresses the Growth Defect of the bon1 Mutant

To reveal additional regulators of SNC1 in the autoimmune mutant bon1, we analyzed genes with expression that is correlated with that of MOS1, a regulator of SNC1 (Li et al., 2010b). A highly correlated expression pattern between two genes under various conditions would suggest that they might be involved in the same biological process. We tested whether mutations in MOS1 coexpressed genes identified from the ATTED-II (http://atted.jp/) could affect the autoimmune phenotypes in the bon1 mutant. Transfer DNA insertion mutants of approximately 30 such genes were crossed to bon1, and F2 or F3 progenies of these crosses were analyzed for segregation of bon1-suppressor phenotypes. Mutations in two genes, including HUB1, seemed to partially suppress the bon1 growth defects. The hub1-4 (referred to as hub1) is an l-o-f mutant with a transfer DNA insertion in the last exon of HUB1 (Alonso et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2008). The hub1 bon1 double mutant had a larger rosette and less twisted leaves compared with the bon1 mutant (Fig. 1A). To determine whether the mutation in HUB1 indeed suppresses the bon1 phenotype, we generated a double mutant between bon1 and another HUB1 l-o-f mutant allele hub1-5 (Liu et al., 2007). The hub1-5 bon1 double mutant exhibited a partially suppressed bon1 phenotype similar to hub1 bon1 (Fig. 1A). We further transformed the hub1 bon1 double mutant with an HUB1 complementary DNA under the control of the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus. Among 18 transgenic plants obtained, 13 plants exhibited a bon1 morphology (Fig. 1B). Seven of these lines were analyzed for HUB1 expression, and two of them had comparable expression with the endogenous HUB1 in the wild-type ecotype Columbia-0 of Arabidopsis (Col-0; Supplemental Fig. S1). Because expression of HUB1 under the control of the 35S promoter did not induce a severe dwarfism in the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2; Dhawan et al., 2009; Himanen et al., 2012), this complementation further indicates that mutation in HUB1 suppresses the bon1 growth phenotype.

Figure 1.

The l-o-f mutation of HUB1 partially suppresses the growth defect in bon1. A, Growth phenotypes of wild-type Col-0, bon1-1 (bon1), hub1-4 (hub1), hub1-5, hub1-4 bon1 (hub1 bon1), and hub1-5 bon1 plants at 3 weeks old. B, Growth phenotypes of wild-type Col-0, bon1-1, hub1, hub1 bon1, and hub1 bon1 transformed with p35S::HUB1 (three lines shown) at 3 weeks old. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

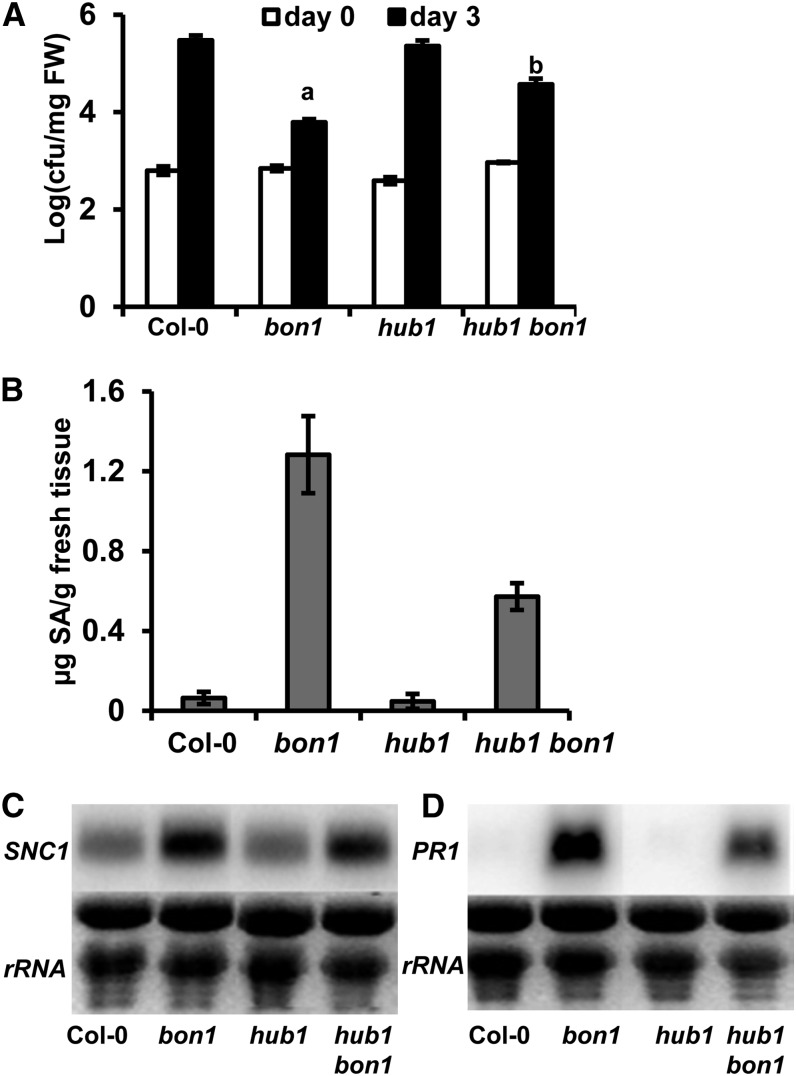

HUB1 Is Required for the Full Expression of Autoimmune Responses in bon1

We determined the effect of HUB1 on autoimmune responses in bon1. The bon1 mutant has an enhanced resistance to the virulent pathogen Pst DC3000 as previously reported (Yang and Hua, 2004; Fig. 2A). This enhanced resistance in bon1 was greatly reduced, although not abolished, in the hub1 bon1 double mutant (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the disease resistance phenotype, the accumulation of SA was dramatically decreased in hub1 bon1 compared with that in bon1 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, up-regulation of SNC1 expression, which is responsible for the bon1 defense phenotype, was drastically reduced in hub1 bon1 (Fig. 2C). The expression of the defense response marker gene PR1 (Fig. 2D) was also decreased. Therefore, HUB1 is required for induction of SNC1 expression and the full activation of SA-mediated immune responses in bon1.

Figure 2.

HUB1 is required for enhanced disease resistance in bon1. A, Growth of Pst DC3000 in Col-0, bon1, hub1, and hub1 bon1 at 0 and 3 d postinoculation. Values represent means ± sds (n = 3); a and b indicate statistically significant differences at different extents from Col-0 determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. B, Quantification of SA levels in Col-0, bon1, hub1, and hub1 bon1. Plants were grown on soil for 3 weeks at 22°C. Data are means ± sds (n = 3) from three biological repeats. C and D, Expression of SNC1 (C) and PR1 (D) in Col-0, bon1, hub1, and hub1 bon1 assayed by RNA blots. Ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) were used as loading controls.

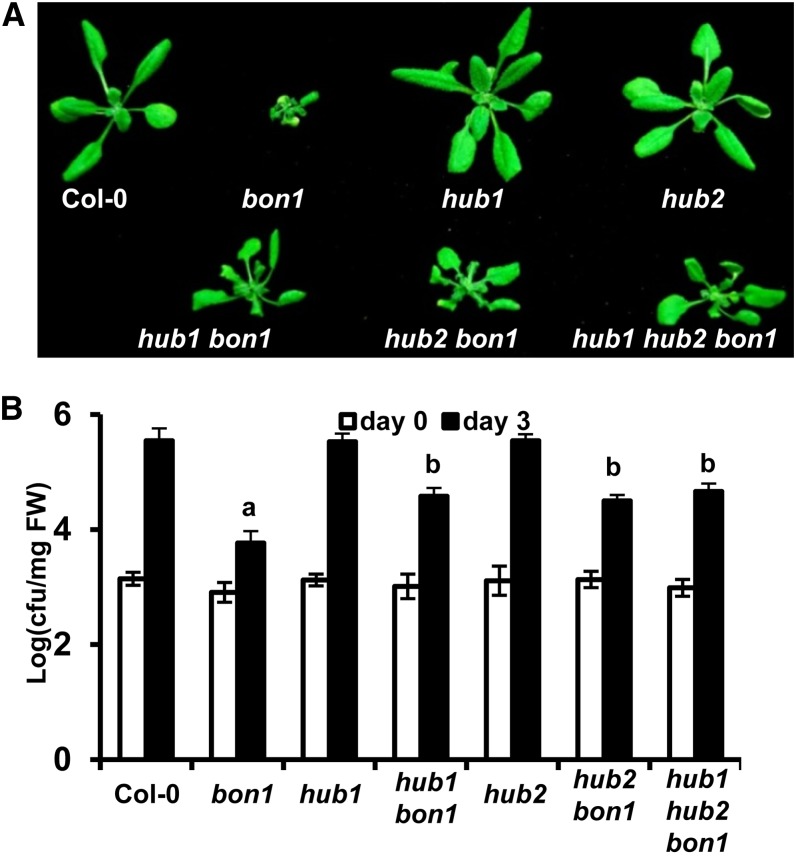

HUB1 and HUB2 Both Mediate Autoimmune Responses in bon1

Proteins encoded by HUB1 and its homolog HUB2 in Arabidopsis can directly interact with each other and were postulated to function together as a dimer to regulate flowering time (Cao et al., 2008). To determine whether HUB2 is also involved in SNC1 regulation, we obtained the hub2-2 l-o-f mutant (referred to as hub2; SALK_071289; Alonso et al., 2003) and constructed the hub2 bon1 double and hub1 hub2 bon1 triple mutants. Similar to that of HUB1, the loss of HUB2 function partially suppressed the bon1 growth defects (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the hub1 hub2 bon1 triple mutant had a similar growth phenotype to the phenotypes of the hub1 bon1 and the hub2 bon1 double mutants (Fig. 3A). Correlated with the growth phenotypes, autoimmune response in bon1 was partially suppressed by the hub2 mutation (Fig. 3B). The resistance to virulent pathogen Pst DC3000 was reduced in hub2 bon1 compared with that in bon1, and there was no further reduction in hub1 hub2 bon1 compared with hub1 bon1 or hub2 bon1 (Fig. 3B). Taken together, HUB2 also mediates autoimmune responses in the bon1 mutant, and HUB1 and HUB2 do not seem to have redundant functions in mediating the autoimmune responses in bon1.

Figure 3.

HUB1 and HUB2 affect bon1-induced defense responses similarly. A, Growth phenotypes of wild-type Col-0, bon1, hub1, hub2-2 (hub2), hub1 bon1, hub2 bon1, and hub1 hub2 bon1 plants at 3 weeks old. B, Growth of Pst DC3000 in wild-type Col-0, bon1, hub1, hub2, hub1 bon1, hub2 bon1, and hub1 hub2 bon1 at 0 and 3 d postinoculation. Values represent means ± sds (n = 3); a and b indicate statistically significant differences at different extents from Col-0 determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. FW, Fresh weight. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

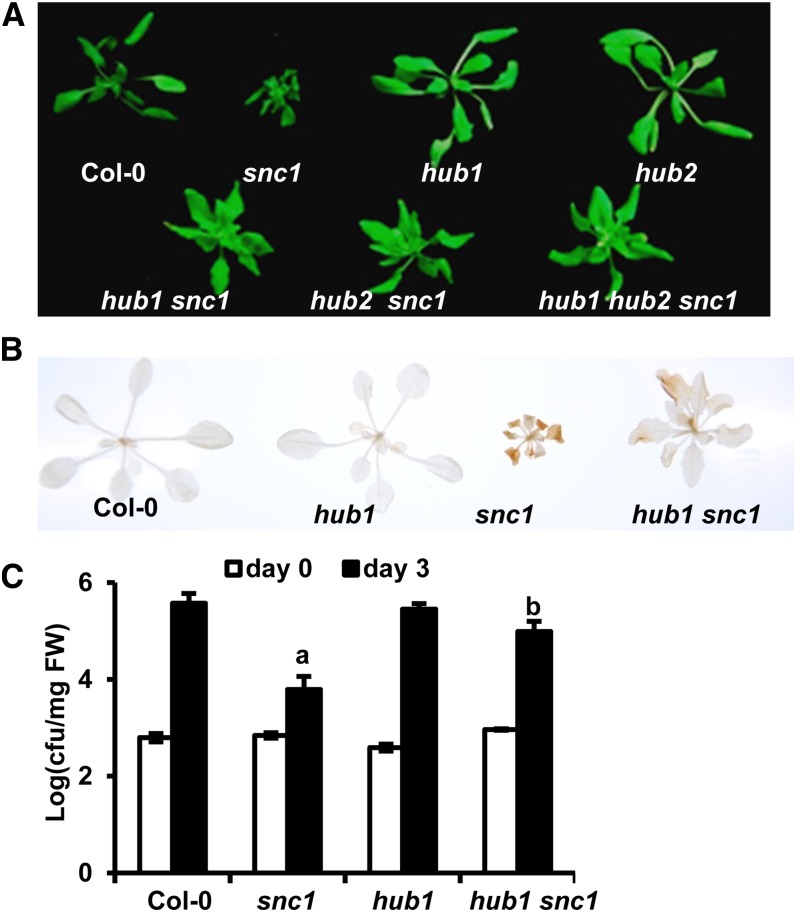

HUB1 Is Partially Required for Autoimmune Responses in snc1

Autoimmune responses in bon1 likely consist of an initial induction of SNC1 transcript and a further amplification by a feedback transcriptional regulation of SNC1 (Li et al., 2007). To determine which steps HUB1 affects, we analyzed the effects of hub1 and hub2 mutations on the snc1 autoimmune phenotypes that likely result from an activation of the SNC1 protein and a subsequent induction of the SNC1 transcript (Zhang et al., 2003). Each of the hub1 and hub2 mutations largely suppressed the dwarf stature and the curly leaf phenotype of snc1 (Fig. 4A). The combination of hub1 and hub2 did not suppress the snc1 phenotype to a further degree (Fig. 4A). The hub1 mutation abolished the high accumulation of reactive oxygen species in snc1 as indicated by staining tissues with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the loss of HUB1 or HUB2 function greatly reduced resistance to Pst DC3000 in snc1 (Fig. 4C). Thus, HUB1 and HUB2 are required for autoimmune responses in snc1 as well as bon1, indicating that HUB1 and HUB2 might be involved in the feedback amplification of SNC1.

Figure 4.

HUB1 is required for autoimmune responses in snc1. A, Growth phenotypes of wild-type Col-0, snc1-1 (snc1), hub1, hub2, hub1 snc1, hub2 snc1, and hub1 hub2 snc1 plants. B, Accumulation of H2O2 is decreased in the hub1bon1 double mutant. Shown is DAB staining of the wild-type Col-0, snc1, hub1, and hub1 snc1 plants. C, Growth of Pst DC3000 in wild-type Col-0, snc1, hub1, and hub1 snc1 at 0 and 3 d postinoculation. Values represent means ± sds (n = 3); a and b indicate statistically significant differences at different extents from Col-0 determined by Student’s t test (P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Bars indicate ses. FW, Fresh weight.

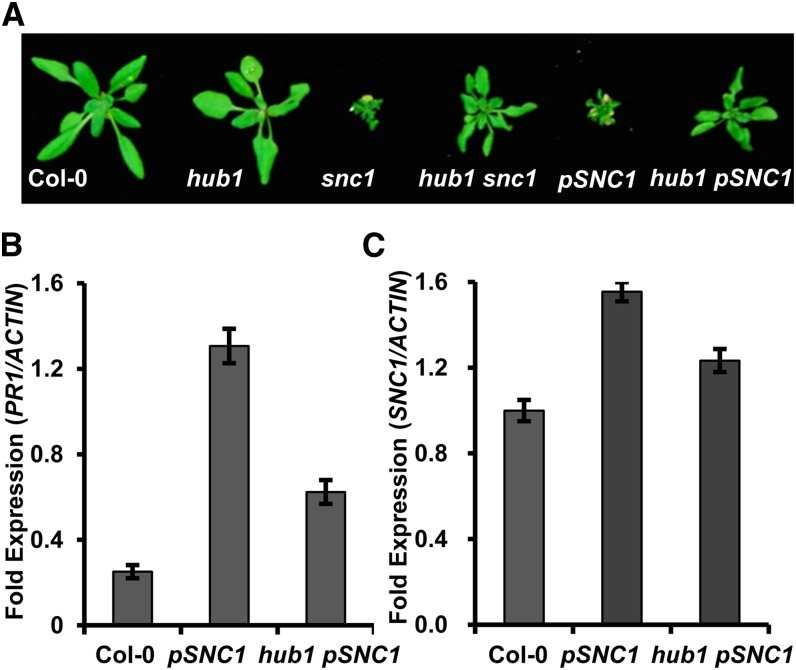

The hub1 Mutation Suppresses the Autoimmune Phenotypes Conferred by the SNC1 Transgene

The SNC1 gene is subject to a regulation exerted at the larger complex locus, and expression of the wild-type genomic fragment of SNC1 as a transgene confers an snc1- and bon1-like phenotype (Li et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2010). This induction of autoimmune phenotype is likely attributed to the loss of transcriptional repression at the endogenous locus followed by a feedback amplification of the SNC1 transcript. We introduced the hub1 mutation to pSNC1::SNC1:GFP transgenic plants, where an SNC1:GFP fusion was expressed under its own promoter (Li et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2010; Mang et al., 2012). The hub1 mutation was found to suppress the dwarf phenotype induced by pSNC1::SNC1:GFP (Fig. 5A). Progenies of hub1/+ pSNC1::SNC1:GFP plants segregated out wild type-looking plants at a frequency of about 25%, and all these wild type-looking plants were hub1 homozygous, indicating a suppression of growth defect by the hub1 mutation (Fig. 5A). Corroborated with the growth phenotype, the up-expression of SNC1 and PR1 in the pSNC1::SNC1:GFP plants was largely abolished by the hub1 mutation (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, unlike MOS1, which regulates SNC1 in a locus-specific manner (Li et al., 2010b), HUB1 regulates SNC1 independent of its locus.

Figure 5.

The hub1 mutation suppresses defense responses induced by the SNC1 transgene. A, Growth phenotypes of wild-type Col-0, hub1, snc1, hub1 snc1, pSNC1::SNC1:GFP, and hub1 pSNC1::SNC1:GFP plants. B, qRT-PCR analysis of PR1 expression in the wild-type Col-0, pSNC1::SNC1:GFP, and hub1 pSNC1::SNC1:GFP. C, qRT-PCR analysis of SNC1 expression in the wild-type Col-0, pSNC1::SNC1:GFP, and hub1 pSNC1::SNC1:GFP. pSNC1, pSNC1::SNC1:GFP. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

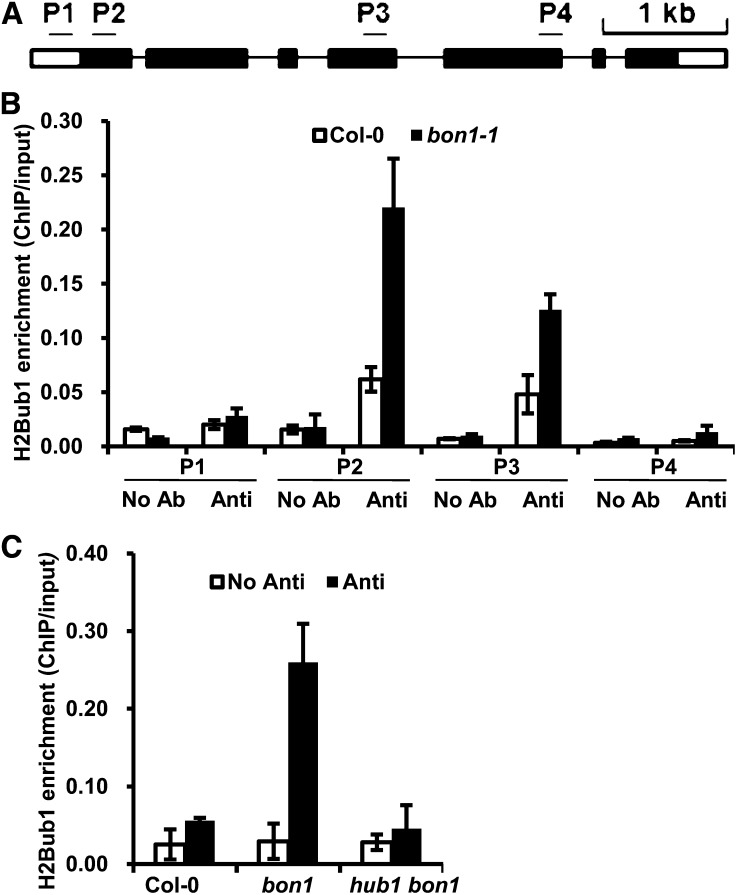

H2B Monoubiquitination at the SNC1 Locus Is Induced in bon1

Because the SNC1 up-regulation in bon1 is dependent on HUB1 and HUB2, we determined whether SNC1 is directly regulated by the HUB1 and HUB2 activity through monoubiquitinating H2B. The level of H2Bub1 at the SNC1 locus was analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Four genomic fragments of SNC1, including P1 at the promoter region and P2 to P4 at coding regions, were analyzed for their association with H2Bub1 using anti-H2Bub1 antibodies (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Table S1). H2Bub1 was enriched by 4- and 3-fold at P2 and P3 regions, respectively, of the SNC1 gene in bon1 compared with the wild-type Col-0 (Fig. 6B). No enrichment was seen in P1 or P4 of the SNC1 locus, and no enrichment was seen in a region of the ACTIN2 gene (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S3; Supplemental Table S1). The H2Bub1 enrichment at the P2 regions in bon1 was abolished in the hub1 bon1 mutant, indicating that HUB1 function is required for H2Bub1 at the SNC1 locus (Fig. 6C). Thus, the SNC1 locus has enhanced H2B monoubiquitination through HUB1 in bon1, contributing to the up-regulation of the SNC1 transcript in the autoimmune mutant bon1.

Figure 6.

H2B monoubiquitination is induced at the SNC1 locus in bon1. A, The structure of the SNC1 genomic region. Primers at the promoter and gene body regions (P1–P4) are used to assess the level of H2Bub1 by ChIP. The black boxes represent exons, the black lines represent introns, and the white boxes represent untranslated regions. B, ChIP analysis of the level of H2Bub1 at the SNC1 locus (P1–P4 as in A) in 2-week-old seedlings of wild type and bon1. Shown is the one biological result with three technical repeats. Two biological repeats were carried out with similar results. C, ChIP analysis of the level of H2Bub1 in the P2 region of SNC1 in Col-0, bon1, and hub1 bon1. Shown is the one biological result with three technical repeats. Two biological repeats were carried out with similar results. Anti, Antibody; No Ab, no antibody.

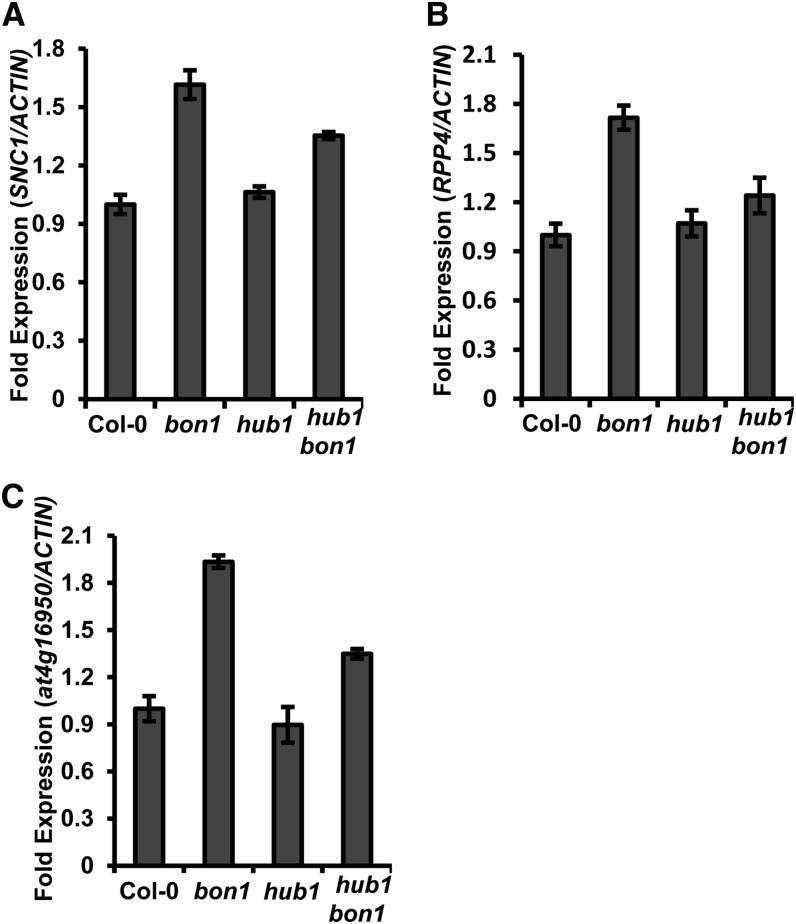

HUB1 Regulates Expression of RPP4 and At4g16950 in the RPP5 Gene Cluster

The SNC1 gene resides in the RPP5 complex locus containing a cluster of R genes that contribute to disease resistance (Noël et al., 1999). Genes in this cluster are found to be coregulated in the snc1 and ball mutants, likely through RNA silencing mechanisms (Stokes et al., 2002; Yi and Richards, 2007; Xia et al., 2013). In the bon1 mutant, two genes in the RPP5 cluster, RPP4 and At4g16950, were up-regulated similarly to SNC1 (Fig. 7), indicating that genes in the RPP5 cluster might be coregulated in bon1 as well. Furthermore, the up-regulation of RPP4 and At4g16950 in bon1 was largely inhibited by the hub1 mutation (Fig. 7, B and C). Therefore, HUB1 modulates expression of multiple genes in the RPP5 cluster.

Figure 7.

HUB1 regulates expression of genes in the RPP5 cluster. The expression of SNC1 (A), RPP4 (B), and At4g19650 (C) in the wild-type Col-0, bon1, hub1, and hub1 bon1 as analyzed by qRT-PCR. Two biological repeats were carried out with similar results. Shown is one biological repeat with three technical repeats.

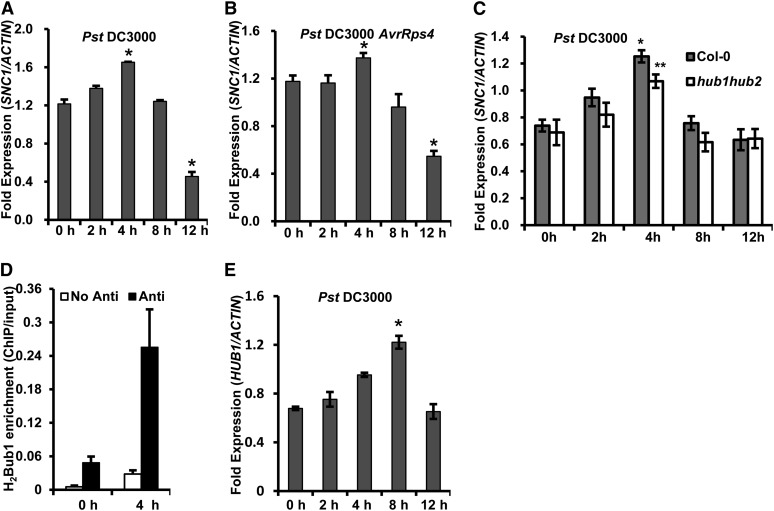

Induction of SNC1 by Pathogen Infection Is Associated with H2Bub1

The SNC1 gene is up-regulated in many autoimmune mutants in addition to bon1 (Zhang et al., 2003; Yang and Hua, 2004; Kim et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010a; Gou et al., 2012). We examined whether SNC1 expression is also induced on pathogen infections. Wild-type plants were inoculated with virulent and avirulent Pst DC3000 strains by spray inoculation, and the SNC1 expressions were investigated by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR; Supplemental Table S2). The SNC1 transcript was rapidly induced by Pst DC3000 at 2 h postinoculation (hpi) and peaked at 4 hpi before it decreased at 12 hpi (Fig. 8A). A similar expression pattern of SNC1, although with a lower amplitude, was observed after inoculation with the avirulent pathogen Pst DC3000 avrRps4 (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Expressions of SNC1 and H2Bub1 at SNC1 are induced by pathogen infection. A to C, SNC1 expression in response to Pst DC3000 (A and C) and Pst DC3000 AvrRps4 (B) in Col-0 (A–C) and hub1hub2 (C). Two- to 3-week-old plants were inoculated with pathogen strains, and RNAs were isolated at the indicated time for qRT-PCR analysis. D, ChIP analysis of the level of H2Bub1 in chromatin at the P2 region of the SNC1 locus after infection by Pst DC3000. Anti, Antibody; No Ab, no antibody. E, HUB1 expression in response to Pst DC3000. Wild-type plants were inoculated with Pst DC3000, and RNAs were isolated at the indicated time for qRT-PCR analysis. Bars indicate ses. *, Significant difference from the control (0 h); **, significant differences between hub1hub2 and Col-0 (P < 0.05 according to Student’s t test).

We subsequently determined whether the up-regulation of SNC1 after pathogen infection is caused by the enhanced H2Bub1 at the SNC1 region. The SNC1 expression on infection in the hub1hub2 double mutant was compared with that in the wild-type Col-0. Although the hub1hub2 double mutation did not affect SNC1 expression at 0, 8, or 12 hpi when SNC1 had a basal expression level, it reduced the SNC1 expression at 4 hpi when it had the highest expression on infection (Fig. 8C). In addition, the level of H2Bub1 at the P2 region of SNC1 after Pst DC3000 inoculation was analyzed by ChIP assay. There was a 3.5-fold increase of H2Bub1 in the P2 region of SNC1 at 4 compared with 0 hpi (Fig. 8D), indicating that H2Bub1 modification occurs at SNC1 during pathogen infection. Therefore, similar to induction in the autoimmune bon1 mutant, induced expression of SNC1 after pathogen infection is also partially dependent on HUB1 and HUB2.

The expression of HUB1 is also influenced by infection of Pst DC3000 strains. It was slightly induced at 4 hpi, peaked at 8 hpi, and decreased to the preinduction level at 12 hpi (Fig. 8E). The up-regulation of HUB1 by pathogen infection prompted us to analyze resistance to bacterial pathogens in the hub1 and hub2 mutants. Consistent with an earlier finding (Dhawan et al., 2009), no significant differences in bacterial growth were observed among hub1, hub1 hub2, and the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting that HUB1 does not have a major impact on resistance to these virulent and avirulent bacterial pathogens.

DISCUSSION

R genes are central regulators of plant immunity, and the activities of R genes are regulated at multiple levels, such as protein activities, as well as transcript amount. Fine tuning R gene expression is important for not only plant defense responses but also, balancing plant immunity, growth, and development. This is exemplified by the large impact of SNC1 expression on growth and immunity, because an increase of its transcript level leads to autoimmune responses and greatly reduced stature (Zhang et al., 2003; Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010b; Zhu et al., 2013). In this study, we show that HUB1 directly modifies the chromatin of the SNC1 locus and regulates the expression of SNC1 and two other genes in the RPP5 gene cluster. HUB1 encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase that monoubiquitinates H2B, and the enrichment of H2Bub1 is usually associated with gene activation (Sun and Allis, 2002; Weake and Workman, 2008; Bourbousse et al., 2012). HUB1-mediated H2Bub1 is required for the activation of FLC and its homologs to control flowering time (Cao et al., 2008). Our results indicate that the H2B at the SNC1 locus is also subject to monoubiquitination by HUB1, which leads to the up-regulation of SNC1 in bon1 (Fig. 6C).

There are two H2B E3 ubiquitin ligases genes, HUB1 and HUB2, in Arabidopsis, and both of them are required for the autoimmunity in bon1 (Fig. 3). No overlapping function was observed for HUB1 and HUB2 in regulating SNC1 expression. Therefore, they may function together in a complex, such as a heterodimer, which was postulated for their roles in flowering time regulation (Cao et al., 2008). The loss of both HUB1 and HUB2 partially suppresses the autoimmune phenotypes in bon1, indicating the existence of an HUB1/2-independent process in regulating SNC1 expression. Because the final expression level of SNC1 is determined by an initial trigger followed by feedback amplification, it is possible that HUB1/2 is responsible for the amplification of SNC1 expression.

A few genes have been identified for the up-regulation of SNC1 in snc1 and/or bon1, and they include MOS1, MOS9, and ATXR7 (Li et al., 2010b; Xia et al., 2013). The mos1-4 mutation suppresses the snc1 phenotype but not the immune responses induced by the SNC1 transgene (Li et al., 2010b). In contrast, hub1 suppresses both snc1 (Fig. 4) and SNC1 transgene-induced immune responses (Fig. 5), suggesting that HUB1 and MOS1 might regulate different steps in SNC1 up-regulation and that MOS1 could function in the initial trigger of SNC1 activation.

ATXR7 encodes a putative histone methyltransferase, and MOS9 and ATXR7 interact with each other to regulate SNC1 expression by H3K4 trimethylation (Xia et al., 2013). Here, we show that H2B monoubiquitination of SNC1 chromatin is induced in bon1 and that the induction is dependent on HUB1 and HUB2 (Fig. 6, B and C). Thus, the SNC1 expression can be regulated by both H3K4 trimethylation and H2B monoubiquitination, and the two modifications might be linked. In yeast, H2B monoubiquitination is required for H3K4 methylation (Dover et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2007). It will be interesting to determine whether one modification is dependent on the other at the SNC1 locus.

Pathogen infection has been reported to change histone modifications levels in some defense response genes (Jaskiewicz et al., 2011; De-La-Peña et al., 2012). Here, we find that the expression of SNC1 can be induced by both virulent and avirulent pathogens (Fig. 8, A and B). The induced SNC1 expression by pathogen infection is associated with H2Bub1 enrichment at SNC1 (Fig. 8D). Our results also indicate that other R genes in the same RPP5 cluster are subject to similar regulations as SNC1. In addition, expression of HUB1 is influenced by pathogen attack (Fig. 8E). Changes in R gene expression are expected to have a role in fine controlling plant immunity, because an initial up-regulation might contribute to a robust defense response to pathogens. The subsequent down-regulation of the R gene may result from pathogen suppression of such up-regulation or a tuning down from the plants to control the spread of cell death induced by R gene activation. However, no differences in resistance to bacterial pathogen strains of Pst DC3000 were observed in the hub1 hub2 mutant compared with the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S4). Because the corresponding effector protein for SNC1 is largely unknown, it is not possible to determine the role of HUB1 in resistance to pathogens carrying the effector. It is possible that HUB1 plays a role in disease resistance to strains of Hyloperonospora parasitica conferred by RPP4 or RPP5, because genes in the RPP4 cluster are coregulated by HUB1. HUB1 is shown to be important for resistance against the necrotrophic fungi pathogen in Arabidopsis (Dhawan et al., 2009), and it would be interesting to reveal the target gene subject to H2Bub1 in that immune response. In sum, the R gene locus can be directly modified by H2Bub1, and chromatin remodeling at the R gene locus might be a mechanism to fine tune immune responses in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were grown on soil at 22°C at approximately 100 μmol m−2 s−1 with relative humidity between 40% and 60%. Plants for pathogen tests were grown under a 12-h-day/12-h-night photoperiod, and plants for morphological phenotyping were grown under constant light.

Transgenic Plant Generation

Agrobactrium tumefaciens stains of GV3101 (Koncz and Schell, 1986) carrying the p35S::HUB1 constructs were used to transform hub1-4 bon1 plants by standard floral dipping. Primary transformants were selected on solid medium containing hygromycin.

RNA Analysis

Total RNAs were extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) from leaves of 2- to 3-week-old plants. Twenty micrograms of total RNA per sample was used for RNA gel-blot analysis according to the standard procedure. RNA gel blots were hybridized with gene-specific, 32P-labeled, single-stranded DNA probes. For qRT-PCR, 1 µg of total RNA was used as a template for first strand complementary DNA synthesis with the SuperScript III Kit (Invitrogen) and an oligo(dT) primer.

Pathogen Resistance Assay

The bacteria strains Pst DC3000, Pseudomonas syringae pv maculicola ES4326, Pst DC3000 AvrRps4, and Pst DC3000 AvrRpt2 were grown for 2 to 3 d on King’s B medium and resuspended at 105 colony forming units/1 mL in a solution of 10 mm MgCl2 and 0.02% (v/v) Silwet L-77. Two-week-old seedlings were dip inoculated with bacterial solution and kept covered for 1 h. The amount of bacteria in plants was analyzed at 1 h (d 0) and 3 d (d 3) after dipping. The aerial parts of three inoculated seedlings were pooled as one sample, and three samples were collected for each genotype and time point. Seedlings were ground in 0.4 mL of 10 mm MgCl2, and serial dilutions of the ground tissue were used to determine the number of colony forming units per 1 mg of fresh leaf tissues.

DAB Staining

The wild-type and mutant plants were grown on soil at 22°C for 2 to 3 weeks. Production of H2O2 was assayed by staining with DAB dissolved in 50 mm Tris-acetate (pH 5.0) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Whole seedlings were placed in the DAB solution and vacuum-infiltrated until the tissues were soaked. The seedlings were then incubated at room temperature in the dark for 24 h before the tissues were cleared by 75% (v/v) ethanol.

SA Content Measurement

Quantification of SA was performed as previously described (Pan et al., 2008).

ChIP Analysis

The ChIP experiment was performed as described previously (Gendrel et al., 2005) with minor modifications. Two-week-old seedlings were harvested; 2 g sample was cross linked by vacuum infiltration with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde solution for 10 min. Isolated nuclei were sonicated on ice water five times for 5 s each with a 20-s pause between sonications, and power setting 2 on a Branson sonifier was used to shear DNA into 500- to 1,000-bp fragments. After preclearing with protein A beads (Sigma), the chromatins isolated were incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal antibodies to H2Bub1 (MediMabs Inc.) at 4°C on a nutator. After reverse cross linking, samples were incubated with 4 µL of ribonuclease A (10 mg/mL) at 37°C for 1.5 h followed by 2 h at 45°C with 4 µL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL). DNA was then purified using the column (QIAGEN) and eluted in 25 µL of water. One microliter DNA was amplified by real-time qRT-PCR. The approach of percentage of input was used to analyze the qRT-PCR data as described (Haring et al., 2007).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Expression of HUB1 in p35S::HUB1 in hub1 bon1.

Supplemental Figure S2. Overexpresssion of HUB1 in wild-type Col-0.

Supplemental Figure S3. H2Bub1 modification at the ACTIN2 locus in Col-0 and bon1.

Supplemental Figure S4. Basal and R gene-mediated defense response in the hub1 and hub2 mutants.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used for ChIP experiments.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used for q-RT-PCR experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center and Dr. Ligeng Ma for mutant seeds, and Dr. Zhilong Bao and Dr. Yan He for assistance with experiments.

Glossary

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Col-0

ecotype Columbia of Arabidopsis 0

- DAB

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine

- hpi

h postinoculation

- l-o-f

loss-of-function

- NB-LRR

nucleotide-binding Leu-rich repeat

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

- SA

salicylic acid

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. IOS–0642289 and IOS–0919914 to J.H.), the China Scholarship Council (to B.Z. and Z.S.), and the China National 973 Plan (grant no. 2012CB114003 to H.D.).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al. (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas R, Abdallat AA, Guo M, Alfano JR, Avramova Z. (2007) Epigenetic control of a transcription factor at the cross section of two antagonistic pathways. Epigenetics 2: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas R, Avramova Z. (2005) Methylation patterns of histone H3 Lys 4, Lys 9 and Lys 27 in transcriptionally active and inactive Arabidopsis genes and in atx1 mutants. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 5199–5207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Krichevsky A, Schornack S, Lahaye T, Tzfira T, Tang YH, Citovsky V, Mysore KS. (2007) Arabidopsis VIRE2 INTERACTING PROTEIN2 is required for Agrobacterium T-DNA integration in plants. Plant Cell 19: 1695–1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke L, Sanchez-Perez GF, Snel B. (2012) Contribution of the epigenetic mark H3K27me3 to functional divergence after whole genome duplication in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol 13: R94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berr A, McCallum EJ, Alioua A, Heintz D, Heitz T, Shen WH. (2010) Arabidopsis histone methyltransferase SET DOMAIN GROUP8 mediates induction of the jasmonate/ethylene pathway genes in plant defense response to necrotrophic fungi. Plant Physiol 154: 1403–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbousse C, Ahmed I, Roudier F, Zabulon G, Blondet E, Balzergue S, Colot V, Bowler C, Barneche F. (2012) Histone H2B monoubiquitination facilitates the rapid modulation of gene expression during Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. PLoS Genet 8: e1002825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Dai Y, Cui S, Ma L. (2008) Histone H2B monoubiquitination in the chromatin of FLOWERING LOCUS C regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 2586–2602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SM, Song HR, Han SK, Han M, Kim CY, Park J, Lee YH, Jeon JS, Noh YS, Noh B. (2012) HDA19 is required for the repression of salicylic acid biosynthesis and salicylic acid-mediated defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J 71: 135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JD. (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-La-Peña C, Rangel-Cano A, Alvarez-Venegas R. (2012) Regulation of disease-responsive genes mediated by epigenetic factors: interaction of Arabidopsis-Pseudomonas. Mol Plant Pathol 13: 388–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan R, Luo H, Foerster AM, Abuqamar S, Du HN, Briggs SD, Mittelsten Scheid O, Mengiste T. (2009) HISTONE MONOUBIQUITINATION1 interacts with a subunit of the mediator complex and regulates defense against necrotrophic fungal pathogens in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 1000–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehlemann G, Wahl R, Horst RJ, Voll LM, Usadel B, Poree F, Stitt M, Pons-Kühnemann J, Sonnewald U, Kahmann R, et al. (2008) Reprogramming a maize plant: transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by the fungal biotroph Ustilago maydis. Plant J 56: 181–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dover J, Schneider J, Tawiah-Boateng MA, Wood A, Dean K, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. (2002) Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6. J Biol Chem 277: 28368–28371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T. (2005) Regulation of the Arabidopsis defense transcriptome. Trends Plant Sci 10: 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury D, Himanen K, Cnops G, Nelissen H, Boccardi TM, Maere S, Beemster GT, Neyt P, Anami S, Robles P, et al. (2007) The Arabidopsis thaliana homolog of yeast BRE1 has a function in cell cycle regulation during early leaf and root growth. Plant Cell 19: 417–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel AV, Lippman Z, Martienssen R, Colot V. (2005) Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat Methods 2: 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou M, Hua J. (2012) Complex regulation of an R gene SNC1 revealed by auto-immune mutants. Plant Signal Behav 7: 213–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou M, Shi Z, Zhu Y, Bao Z, Wang G, Hua J. (2012) The F-box protein CPR1/CPR30 negatively regulates R protein SNC1 accumulation. Plant J 69: 411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haring M, Offermann S, Danker T, Horst I, Peterhansel C, Stam M. (2007) Chromatin immunoprecipitation: optimization, quantitative analysis and data normalization. Plant Methods 3: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyse KS, Weber SE, Lipps HJ. (2009) Histone modifications are specifically relocated during gene activation and nuclear differentiation. BMC Genomics 10: 554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himanen K, Woloszynska M, Boccardi TM, De Groeve S, Nelissen H, Bruno L, Vuylsteke M, Van Lijsebettens M. (2012) Histone H2B monoubiquitination is required to reach maximal transcript levels of circadian clock genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J 72: 249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J. (2013) Modulation of plant immunity by light, circadian rhythm, and temperature. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Grisafi P, Cheng SH, Fink GR. (2001) Plant growth homeostasis is controlled by the Arabidopsis BON1 and BAP1 genes. Genes Dev 15: 2263–2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambunathan N, Siani JM, McNellis TW. (2001) A humidity-sensitive Arabidopsis copine mutant exhibits precocious cell death and increased disease resistance. Plant Cell 13: 2225–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz M, Conrath U, Peterhänsel C. (2011) Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. EMBO Rep 12: 50–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Gao F, Bhattacharjee S, Adiasor JA, Nam JC, Gassmann W. (2010) The Arabidopsis resistance-like gene SNC1 is activated by mutations in SRFR1 and contributes to resistance to the bacterial effector AvrRps4. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koncz C, Schell J. (1986) The promoter of TL-DNA gene 5 controls the tissue-specific expression of chimeric genes carried by a novel type of Agrobacterium binary vector. Mol Gen Genet 204: 383–396 [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Shukla A, Schneider J, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Florens L, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. (2007) Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell 131: 1084–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li S, Bi D, Cheng YT, Li X, Zhang Y. (2010a) SRFR1 negatively regulates plant NB-LRR resistance protein accumulation to prevent autoimmunity. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Yang SH, Yang HJ, Hua J. (2007) The TIR-NB-LRR gene SNC1 is regulated at the transcript level by multiple factors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20: 1449–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YZ, Tessaro MJ, Li X, Zhang YL. (2010b) Regulation of the expression of plant Resistance gene SNC1 by a protein with a conserved BAT2 domain. Plant Physiol 153: 1425–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Koornneef M, Soppe WJ. (2007) The absence of histone H2B monoubiquitination in the Arabidopsis hub1 (rdo4) mutant reveals a role for chromatin remodeling in seed dormancy. Plant Cell 19: 433–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang HG, Qian W, Zhu Y, Qian J, Kang HG, Klessig DF, Hua J. (2012) Abscisic acid deficiency antagonizes high-temperature inhibition of disease resistance through enhancing nuclear accumulation of resistance proteins SNC1 and RPS4 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 1271–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March-Díaz R, García-Domínguez M, Lozano-Juste J, León J, Florencio FJ, Reyes JC. (2008) Histone H2A.Z and homologues of components of the SWR1 complex are required to control immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant J 53: 475–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël L, Moores TL, van Der Biezen EA, Parniske M, Daniels MJ, Parker JE, Jones JD. (1999) Pronounced intraspecific haplotype divergence at the RPP5 complex disease resistance locus of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11: 2099–2112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma K, Thorgrimsen S, Malinovsky FG, Fiil BK, Nielsen HB, Brodersen P, Hofius D, Petersen M, Mundy J. (2010) Autoimmunity in Arabidopsis acd11 is mediated by epigenetic regulation of an immune receptor. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XQ, Welti R, Wang XM. (2008) Simultaneous quantification of major phytohormones and related compounds in crude plant extracts by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry 69: 1773–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan TK, Hartzog GA. (2010) Histone H3K4 and K36 methylation, Chd1 and Rpd3S oppose the functions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spt4-Spt5 in transcription. Genetics 184: 321–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Grosschedl R. (2007) Dynamics and interplay of nuclear architecture, genome organization, and gene expression. Genes Dev 21: 3027–3043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TL, Kunkel BN, Richards EJ. (2002) Epigenetic variation in Arabidopsis disease resistance. Genes Dev 16: 171–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun ZW, Allis CD. (2002) Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418: 104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakura S, Ueno Y, Tagami H, Kitakura S, Machida C, Wabiko H, Aiba H, Otten L, Tsukagoshi H, Nakamura K, et al. (2007) An oncoprotein from the plant pathogen agrobacterium has histone chaperone-like activity. Plant Cell 19: 2855–2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lijsebettens M, Grasser KD. (2010) The role of the transcript elongation factors FACT and HUB1 in leaf growth and the induction of flowering. Plant Signal Behav 5: 715–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weake VM, Workman JL. (2008) Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell 29: 653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S, Cheng YT, Huang S, Win J, Soards A, Jinn TL, Jones J, Kamoun S, Chen S, Zhang Y, et al. (2013) Regulation of transcription of nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat-encoding genes SNC1 and RPP4 via H3K4 trimethylation. Plant Physiol 162: 1694–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Hua J. (2004) A haplotype-specific Resistance gene regulated by BONZAI1 mediates temperature-dependent growth control in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 1060–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Yang H, Grisafi P, Sanchatjate S, Fink GR, Sun Q, Hua J. (2006) The BON/CPN gene family represses cell death and promotes cell growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J 45: 166–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Feng H, Yu Y, Dong A, Shen WH. (2013) SDG2-mediated H3K4 methylation is required for proper Arabidopsis root growth and development. PLoS ONE 8: e56537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Richards EJ. (2007) A cluster of disease resistance genes in Arabidopsis is coordinately regulated by transcriptional activation and RNA silencing. Plant Cell 19: 2929–2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Goritschnig S, Dong X, Li X. (2003) A gain-of-function mutation in a plant disease resistance gene leads to constitutive activation of downstream signal transduction pathways in suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1. Plant Cell 15: 2636–2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Zhang L, Duan J, Miki B, Wu K. (2005) HISTONE DEACETYLASE19 is involved in jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 1196–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Du B, Qian J, Zou B, Hua J. (2013) Disease resistance gene-induced growth inhibition is enhanced by rcd1 independent of defense activation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 161: 2005–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qian W, Hua J. (2010) Temperature modulates plant defense responses through NB-LRR proteins. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurawski DV, Mumy KL, Faherty CS, McCormick BA, Maurelli AT. (2009) Shigella flexneri type III secretion system effectors OspB and OspF target the nucleus to downregulate the host inflammatory response via interactions with retinoblastoma protein. Mol Microbiol 71: 350–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.