Coenzyme A reductases contribute to the production of triterpene saponin in ginseng.

Abstract

Ginsenosides are glycosylated triterpenes that are considered to be important pharmaceutically active components of the ginseng (Panax ginseng ‘Meyer’) plant, which is known as an adaptogenic herb. However, the regulatory mechanism underlying the biosynthesis of triterpene saponin through the mevalonate pathway in ginseng remains unclear. In this study, we characterized the role of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) concerning ginsenoside biosynthesis. Through analysis of full-length complementary DNA, two forms of ginseng HMGR (PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2) were identified as showing high sequence identity. The steady-state mRNA expression patterns of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 are relatively low in seed, leaf, stem, and flower, but stronger in the petiole of seedling and root. The transcripts of PgHMGR1 were relatively constant in 3- and 6-year-old ginseng roots. However, PgHMGR2 was increased five times in the 6-year-old ginseng roots compared with the 3-year-old ginseng roots, which indicates that HMGRs have constant and specific roles in the accumulation of ginsenosides in roots. Competitive inhibition of HMGR by mevinolin caused a significant reduction of total ginsenoside in ginseng adventitious roots. Moreover, continuous dark exposure for 2 to 3 d increased the total ginsenosides content in 3-year-old ginseng after the dark-induced activity of PgHMGR1. These results suggest that PgHMGR1 is associated with the dark-dependent promotion of ginsenoside biosynthesis. We also observed that the PgHMGR1 can complement Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) hmgr1-1 and that the overexpression of PgHMGR1 enhanced the production of sterols and triterpenes in Arabidopsis and ginseng. Overall, this finding suggests that ginseng HMGRs play a regulatory role in triterpene ginsenoside biosynthesis.

Ginseng (Panax ginseng ‘Meyer’), which belongs to the Araliaceae family, is a perennial herbaceous plant. It has been cultivated for over 2,000 years as a medicinal plant for its highly valued roots. The root of ginseng contains polyacetylenes, polysaccharides, peptidoglycans, phenolic compounds, and saponin (Kitagawa et al., 1987; Park, 1996; Radad et al., 2006). The triterpene saponins, referred to as ginsenosides, have been especially noted as active compounds contributing to the various efficacy of ginseng. Triterpenoid saponins are a class of secondary metabolites that are produced by a large number of plant species and predominantly found in dicot plants. They exhibit considerable structural diversity and notable biological activity (Hostettmann and Marston, 1995; Augustin et al., 2011). Ginsenosides are found exclusively in the plant genus Panax, with a content by dry weight of 4% (w/w) in the root (Shibata, 2001) and up to 6–10% (w/w) in the leaf, berry, and root hair (Shi et al., 2007). More than 150 naturally occurring ginsenosides have been isolated from Panax spp. (Shi et al., 2010). Among them, more than 40 ginsenosides have been isolated and identified from white and red ginseng from ginseng, showing different biological activities based on their structural differences (Gillis, 1997; Fuzzati, 2004; Xie et al., 2005; Lü et al., 2009; Tung et al., 2009).

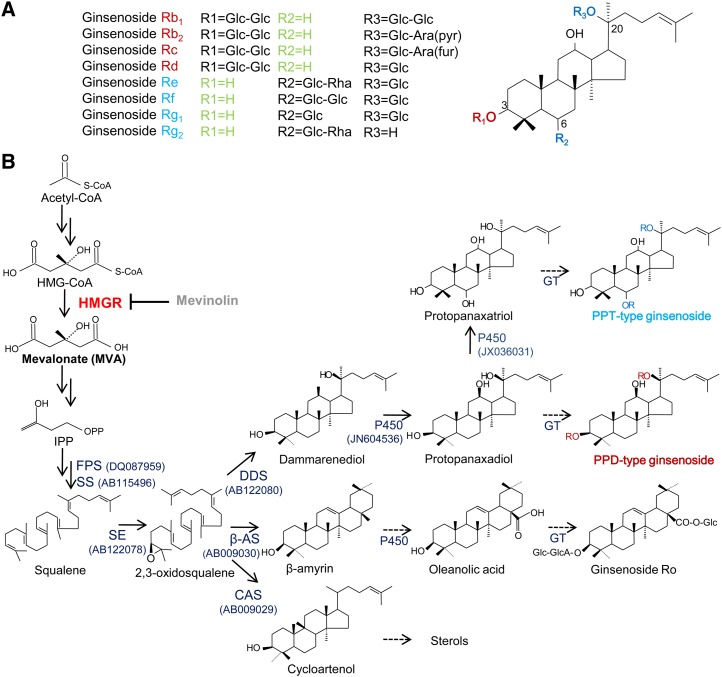

The main ginsenosides, constituting more than 80% of the total ginsenosides, are glycosides that contain an aglycone with a dammarane skeleton (Fig. 1A). They include protopanaxadiol-type saponins (where sugar moieties are attached to the β-OH at C-3 and/or C-20), such as ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd, and protopanaxatriol-type saponins (where sugar moieties are attached to the α-OH at C-6 and/or the β-OH at C-20), such as ginsenosides Re, Rg1, Rg2, and Rf (Kim et al., 1987). The oleanane group has a pentacyclic structure, and only one ginsenoside, Ro, was identified, which is found in minor amounts in ginseng. These ginsenoside compounds contribute to the various pharmacological effects of ginseng, including antiaging (Cheng et al., 2005), antidiabetes (Attele et al., 2002), antiinflammatory (Wu et al., 1992), and anticancer activities, such as the inhibition of tumor-induced angiogenesis (Nakajima et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2000; Yue et al., 2007) and prevention of tumor invasion and metastasis (Sato et al., 1994; Mochizuki et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Biochemical pathway for the biosynthesis of ginseng saponins. A, Classification of main ginsenosides based on attached glycosides and the dammarendiol-type structure. Ara (fur), α-l-Arabinofuranosyl; Ara (pyr), α-l-glucopyranosyl; Glc, β-d-glucopyranosyl; Rha, α-l-rhamnopyranosyl. B, Ginsenoside biosynthesis pathway. β-AS, β-Amyrin synthase; CAS, cycloartenol synthase; DDS, dammarenediol synthase; FPS, farnesyl diphosphate synthase; GT, glucosyltransferase; Mev, a competitive inhibitor of HMGR; PPD, protopanaxadiol type; PPT, protopanaxatriol type; P450, cytochrome P450. Dotted line displays putative pathway. Reported enzymes in ginseng are shown with the National Center for Biotechnology Information accession numbers in parentheses. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Ginsenosides are synthesized from the 30-carbon intermediate 2,3-oxidosqualene (a common precursor of sterols), which undergoes additional cyclization, hydroxylation, and glycosylation (Fig. 1B). Triterpene saponins, including ginsenosides, are derived from a universal precursor, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), which can be synthesized through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway in the cytosol (conserved in some prokaryotes and all eukaryotes) and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) in the plastids. The MVA pathway is course controlled by the key regulatory enzyme 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGR; EC 1.1.1.34; Bach, 1986). HMGR is known as a rate-limiting enzyme of the MVA isoprene pathway in plants (Bach and Lichtenthaler, 1982) and mammals (Goldstein and Brown, 1990). Because it is also known for rate-controlling cholesterol biosynthesis, its role in human health has been extensively studied. The inhibition of HMGR by statin has been applied as a major strategy for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and blood pressure reduction (Liao and Laufs, 2005). In contrast to the single HMGR in animals, plant HMGR is encoded by a multigene family, where the different isoforms exhibit spatial and temporal gene expression patterns. Two genes (named HMG1 and HMG2) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) encode two HMGR isozymes with basically the same structural organization and intracellular localization, with one of them existing in a short form and one of them existing in a long form. However, the gene expression profiles of HMG1 and HMG2 are different (Lumbreras et al., 1995). The broad expression of HMG1 suggests that it may encode a housekeeping form of HMGR; correspondingly, the loss of function mutation of HMG1 caused senescence and sterility as well as a dwarf phenotype, all of which are likely related to the reduced sterol content (Suzuki et al., 2004). In contrast, hmg2 mutant did not display any distinct phenotype; hmg1 hmg2 double mutants are not viable because of the requirement of two genes for gametophyte development (Suzuki et al., 2009). Both HMG1 and HMG2 genes were also shown to play a major role in the biosynthesis of triterpene metabolites (Ohyama et al., 2007).

Although many reports reveal the pharmacological effects of ginsenosides and deal with the mass production of ginsenosides by genetic engineering and biotechnology, little is known about the regulatory mechanism of ginsenoside biosynthesis at molecular and biochemical levels in the ginseng plant. The lack of genome sequence information has led to several attempts to clone complete complementary DNA (cDNA) encoding enzymes involved in the postsqualene step (indicated according to the accession number in Fig. 1B; Kushiro et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2004; Han et al., 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012; Kim et al., 2010). This study shows the isolation of the two full-length cDNA sequences together with the promoter sequences of HMGRs with structural and functional features in the ginseng plant. Phylogenetic analysis, the investigation of expression profiles of two ginseng HMGR genes (PgHMGRs), and the functional characterization of PgHMGR1 in genetic, molecular, and biochemical ways by heterologous overexpression in Arabidopsis and homologous ginseng plant were also carried out. Our findings indicate that PgHMGR1 is a functional ortholog of Arabidopsis HMGR1 (AtHMGR1), that both PgHMGRs are specifically tissue and age expressed, and that PgHMGR1 plays a regulatory role in the formation of triterpene ginsenosides in ginseng as well as other specialty plants (Singh et al., 2010; Alam and Abdin, 2011; Suwanmanee et al., 2013).

RESULTS

Isolation and Sequence Analysis of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2

To identify the first committed enzyme in the MVA pathway for the biosynthesis of isoprenoids, two EST clones coding PgHMGR (EC 1.1.1.34) were selected from previously constructed EST libraries from 14-year-old ginseng and hairy roots (Kim et al., 2006). Using RACE PCR, full-length cDNA sequences of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were obtained. PgHMGR1 has a length of 1,722 bp encoding 573 amino acids, whereas PgHMGR2 has a length of 1,785 bp encoding 594 amino acids (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Moreover, a full genomic DNA sequence of each PgHMGR with the promoter sequence was obtained by genomic DNA walking. Both genes contain four exons and three introns (Supplemental Fig. S3A), which are typical features of the HMGR genes from other plant species. PgHMGR2 is 63 bp longer than PgHMGR1 in the first exon region, although the other three exons are the same length. The promoter region of PgHMGR1 contains G box (CACGTG), whereas that of PgHMGR2 does not (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 also show conserved domains (Supplemental Figs. S3B, S4, and S5), which are assumed to be characteristics of HMGR (Campos and Boronat, 1995). Both proteins contain a motif rich in arginines (RRR; Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2), which is predicted to be specific for their retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; Schutze et al., 1994). The catalytic domains of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 possess three catalytic active residues (EGC, DKK, and GQD) in the three conserved motif sequences predicted by Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation (Supplemental Figs. S3B and S4). This finding demonstrates that the features of HMGR are similar to the features of Cantharanthus roseus, which shows the active sites that are responsible for the binding of HMG-CoA and NADPH2 (Abdin et al., 2012).

PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 Are Predominantly Expressed in Roots

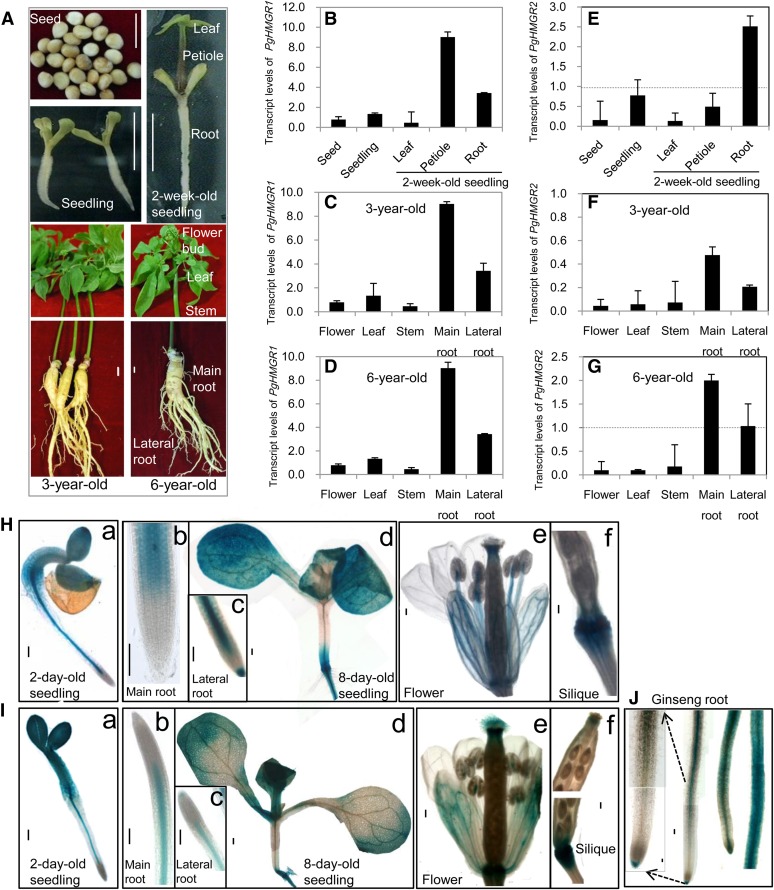

An age-dependent increase of ginsenosides has been reported in perennial ginseng root (Shi et al., 2007). To investigate the expression patterns of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2, quantitative reverse transcription (qRT) -PCR was performed using the ginseng seed, whole seedling, leaf, petiole, and root from a 2-week-old seedling and the flower, leaf, stem, main root, and lateral root of 3- and 6-year-old plants (Fig. 2A). A distinct anatomical feature of ginseng is the long petiole structure, with a relatively shortened stem in 2-week-old seedlings (Fig. 2A). The number of leaf petioles in the ginseng plant increases with the number of cultivation years, and the ginseng plant possesses five leaves at the age of 2 years. In the petioles of 2-week-old seedlings (Fig. 2B), PgHMGR1 was the most highly expressed, whereas PgHMGR2 was relatively weakly expressed. In 3-year-old ginseng (at which time most of the known ginseng organs are already formed) and 6-year-old ginseng, PgHMGR1 was expressed most abundantly in main roots and lateral roots (Fig. 2, C and D). Interestingly, PgHMGR1 expression was high in both 3- and 6-year-old ginseng at a significantly similar level (Fig. 2, C and D). PgHMGR2 was expressed at almost the same level as PgHMGR1 in the roots of seedlings, and its expression gradually increased as it aged (Fig. 2, E to G). These results suggest that PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 are necessary for organ development, especially in roots. PgHMGR1 may also play a role in general metabolites production, whereas PgHMGR2 may play a role in age-dependent specific metabolites production in roots. When the promoter sequence of PgHMGR1 (−1,317 to 1 bp), which was fused with GUS (pHMGR1::GUS), was transformed into a ginseng adventitious root, it was highly expressed in the whole root, with more restriction in the vasculature and root tip (Fig. 2J). When pHMGR1::GUS and pHMGR2::GUS were expressed in Arabidopsis, expressions were also observed in the whole-root vasculature (Fig. 2, Hb and Ib) and an 8-d-old main root tip (Fig. 2, Hc and Ic), similar to the ginseng plant. This finding suggests that Arabidopsis is an ideal plant for additional functional characterization of PgHMGR. The precise expression of pHMGRs::GUS in the overall tissues of a germinating embryo (Fig. 2, Ha and Ia), cotyledon, true leaf, and root was also observed in Arabidopsis (Fig. 2, Hd and Id). GUS expression was high in the filament, flower sepal, and pistil style (Fig. 2, He and Ie), as well as the junction between the silique and pedicel of a 50-d-old plant (Fig. 2, Hf and If).

Figure 2.

Organ-specific expression patterns of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2. A, Ginseng materials of different ages were used for qRT-PCR. Bars = 1 cm. B, Steady-state transcription levels of PgHMGR1 in ginseng seed, 1-week-old seedling, and leaf, petiole, and roots of 2-week-old seedlings. C and D, Steady-state transcription levels of PgHMGR1 in flower buds, leaves, stem, main roots, and lateral roots of 3- and 6-year-old ginseng. E to G, Steady-state transcription levels of PgHMGR2 were analyzed using the same tissue as with PgHMGR1. The Ct value for each gene was normalized to the Ct value for β-actin and calculated relative to a calibrator using the equation 2−ΔCt. Data represent the mean ± se of three independent replicates. H and I, Histochemical analysis of GUS expression in transgenic Arabidopsis plants harboring the pHMGR1::GUS and pHMGR2::GUS at different developmental stages. a, GUS expression in 2-d-old germinated seedlings. b, Main roots. c, Lateral roots. d, True leaves and cotyledons of 8-d-old seedlings. e, Mature flowers. f, Siliques of 50-d-old plants. J, pHMGR1::GUS expression is shown in the root vasculature and root tip of ginseng. Bars in H to J = 100 µm. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Activity of HMGR Is Positively Correlated with Ginsenoside Production

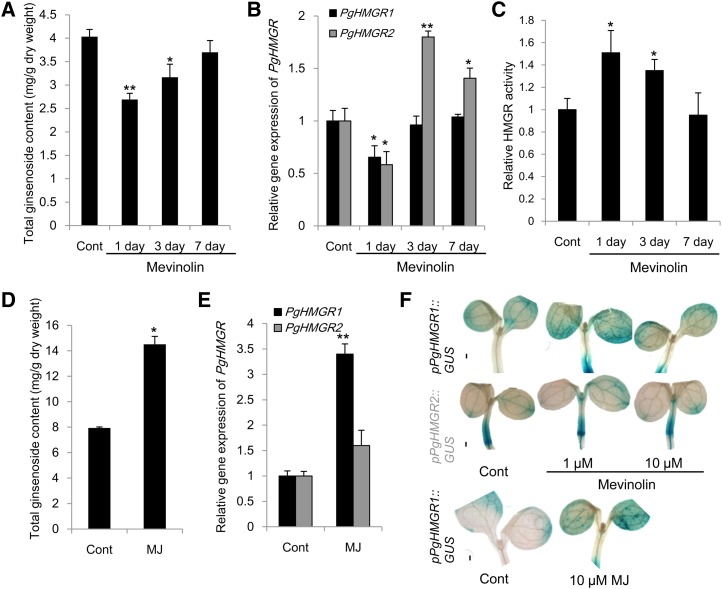

To understand whether HMGR activity is involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis, the inhibition of HMGR activity by mevinolin (Mev) was conducted. Mev (6α-methylcompactin), also referred to as lovastatin, competitively inhibits the binding of the HMG-CoA substrate to the active site of the HMGR enzyme and consequently, blocks the synthesis of cytosolic IPP (Bach and Lichtenthaler, 1982) and phytosterol biosynthesis (Bach and Lichtenthaler, 1987; Bach et al., 1990). Mev treatment for 1 d in 4-week-old adventitious roots significantly decreased the total contents of major ginsenosides by about 34% compared with the control plants (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S6). This result shows that the ginsenosides are rapidly turned over. Transcripts of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were initially down-regulated within 1 d, and PgHMGR1 started to become stabilized (Fig. 3B). This finding indicates that PgHMGR2 follows an independent regulatory pathway, possibly through posttranscriptional regulation. However, it is observed that the metabolic fluctuation of ginsenoside is more correlated with HMGR activity (Fig. 3C). Additionally, methyl jasmonate (MJ), known as an elicitor of triterpene biosynthesis, increased the major ginsenoside contents as well as the transcripts of PgHMGR1 in ginseng adventitious root (Fig. 3, D and E; Supplemental Fig. S6). The mismatching of the ginsenosides contents with the transcript levels of the HMGR genes and the enzyme activity of HMGR might be explained by the specific posttranscriptional and feedback regulations of HMGR. The promoter::GUS fusion of PgHMGR1 also supports the observed results (Fig. 3, B, E, and F), and these results corroborate a role of HMGRs in ginsenoside biosynthesis.

Figure 3.

Activity of HMGR enzyme is associated with the production of ginsenoside. Mev (10 µM), an inhibitor of HMGR, was treated to 4-week-old adventitious roots for 1, 3, and 7 d. A, Total contents of major ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Rf, Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd; milligrams per gram dry weight). Gene expression of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 (B) and relative HMGR activity (C) were analyzed. MJ (10 µM), an elicitor of saponin biosynthesis, was treated to adventitious roots for 3 d. Total contents of major ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Rf, Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd; milligrams per gram dry weight; D) and gene expression (E) were analyzed. Vertical bars indicate the mean value ± se from five independent experiments. The Ct value for each gene was normalized to the Ct value for β-actin and calculated relative to a calibrator using the equation 2−ΔΔCt. * and **, Significantly different from control at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively. F, pHMGR1::GUS- and/or pHMGR2::GUS-expressing seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog for 4 d were treated with ethanol control (Cont), 1 or 10 µm Mev, and 10 µm MJ for 3 h. Bar = 100 µm. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

PgHMGR1 Is Dark Dependent and Possibly Associated with Ginseng Shadowing Growth

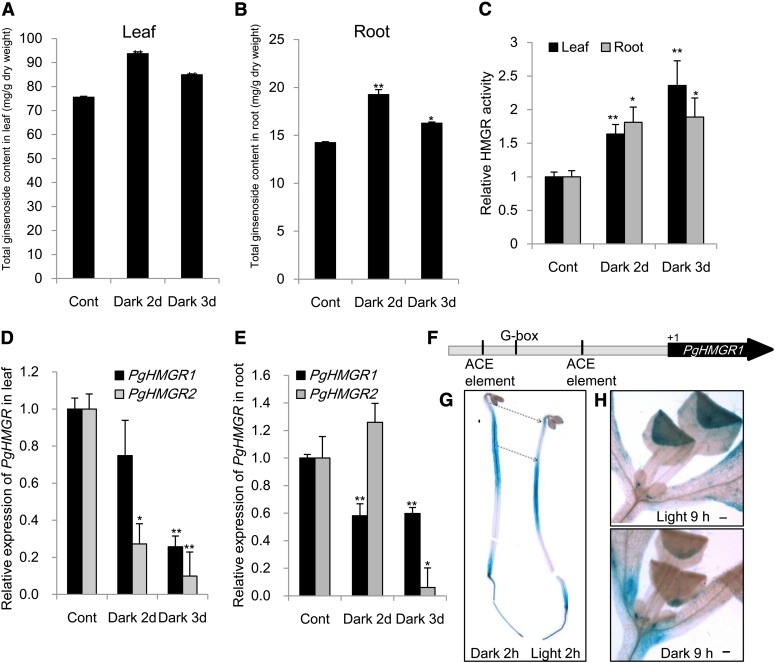

The dark-dependent hypocotyl expression pattern of pHMGR1::GUS suggested the hypothesis that ginsenoside biosynthesis might be regulated by dark treatment. Placing ginseng plants under completely dark conditions for 48 h caused a dramatic increase of ginsenoside contents compared with the controls grown under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark condition (Fig. 4, A and B). Dark conditions for 72 h also resulted in an increase of ginsenosides at a relatively weak level compared with that for 48 h. However, the HMGR activity gradually increased in both the leaves and roots for up to 3 d (Fig. 4C). This result indicates that, up to a certain threshold level, the activity of HMGRs positively up-regulates the ginsenosides contents. It is also considered that the contents of several individual ginsenosides show independent modulation, where Rb1 in the leaf and Rg2 in the root are not significantly changed (Supplemental Fig. S7). Transcripts of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were significantly decreased in the ginseng leaf and root in dark conditions (Fig. 4, D and E). The behavior of PgHMGR2 in the root somewhat differs from that of PgHMGR1, and this result is similar to that seen in the adventitious roots (Fig. 3). PgHMGR2 seems to follow a different posttranscriptional regulation pathway in roots but did not play a major role in altering the final production of ginsenosides (Figs. 3 and 4). The promoter sequence of PgHMGR1 contains a G box, which is known as a putative phytochrome-interacting factor3 (PIF3) binding motif (Fig. 4F). Thus, the precise expression of pHMGR1::GUS was analyzed further in different developmental stages. The activity pHMGR1::GUS was differentially modulated by light exposure in the leaf and hypocotyl (Fig. 4G). GUS expression was induced in the hypocotyl of a 4-d-etiolated seedling and reversed by light exposure within 2 h. However, its expression after dark treatment decreased in the 7-d-old seedling, where true leaves are emerged (Fig. 4H). These results show that the transcripts of PgHMGRs are dark-dependently regulated in different developmental stages and ultimately, affect the ginsenoside production.

Figure 4.

Continuous dark treatment for 2 to 3 d increased ginsenoside contents and HMGR activity. A and B, Total contents of major ginsenosides (ginsenoside Rg1, Re, Rf, Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd) in the leaves and roots was increased by the dark. Vertical bars indicate the mean value ± se from three independent experiments. C, Relative activity of HMGR in ginseng leaves and roots. Data represent mean value ± se (n = 10). D and E, Gene expression of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 in leaves and roots was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The Ct value for each gene was normalized to the Ct value for β-actin and calculated relative to a calibrator using the equation 2−ΔΔCt. Data represent mean value ± se (n = 5). *, Significantly different from the control at P < 0.05; **, significantly different from the control at P < 0.01. F, Putative PIF3 binding motifs are found on the G box or the ACGT-containing (ACE) element of the analyzed promoter of the PgHMGR1 gene that are not found in PgHMGR2 by Plantpan. G, Hypocotyl expression of pHMGR1::GUS was decreased by 2 h of light exposure in 4-d-old etiolated seedlings. H, Expression pHMGR1::GUS was decreased by 9 h of darkness in true leaves of 10-d light-grown seedlings. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Subcellular Localizations of PgHMGR1 in Arabidopsis

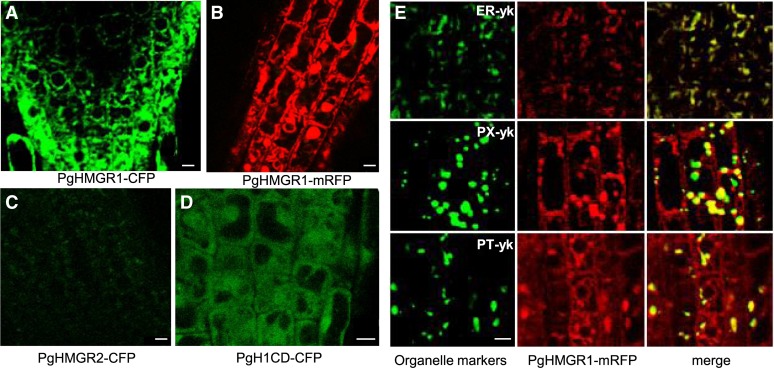

Fractionation analysis identified that plant HMGR is located in three subcellular sites: plastids, mitochondria, and ER (Brooker and Russell, 1975; Wilson and Russell, 1992). Despite the observed enzymatic activity in several organelles, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy and immunogold electron microscopy analyses showed that AtHMGR1 is localized into the ER and in the unidentified spherical vesicles that were not colocalized with peroxisomal catalase (Leivar et al., 2005). Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) or monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) was tagged in the C-terminal ends of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 to verify subcellular localization patterns by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Both PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were localized in the intracellular vesicles (Fig. 5, A to C). To verify the spherical vesicles and other unidentified vesicles, mRFP-tagged PgHMGR1 lines were crossed with ER (ER-yk), peroxisome (PX-yk), and plastid (PT-yk) markers; all markers were tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). PgHMGR1 was completely comerged with ER and plastid as well as partially comerged with peroxisome (PX; Fig. 5E). The catalytic domain of PgHMGR1 was localized in the cytosol (Fig. 5D), similar to the case of Arabidopsis HMGR1 (Leivar et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of PgHMGR1, PgHMGR2, and the catalytic domain of PgHMGR1. A and B, Fluorescent images of PgHMGR1-CFP and PgHMGR1-mRFP were visualized by a confocal laser scanning microscope. C, A fluorescent image of PgHMGR2-CFP was visualized with green color. D, The catalytic domain of PgHMGR1 tagged with CFP at the C terminus was localized in the cytosol. E, Fluorescent signals of PgHMGR1-mRFP merged with ER-yk, PX-yk, and PT-yk. Bars = 5 µm. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Overexpression of PgHMGR1 Enhances Production of Triterpenes in Arabidopsis and Ginseng

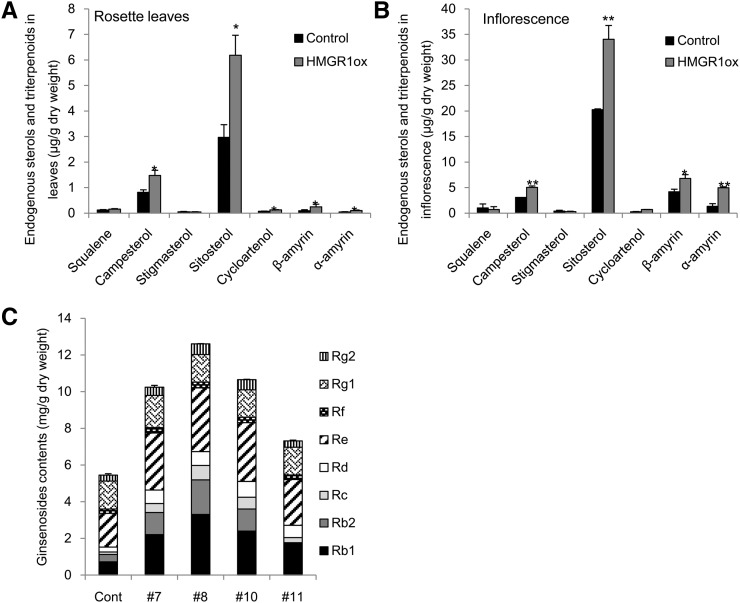

To investigate whether increased HMGR activity contributes to metabolite profiles, the sterol contents of overexpression lines (HMGR1ox) in Arabidopsis were analyzed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Higher plants synthesize a mixture of phytosterols, including campesterol, stigmasterol, and β-sitosterol (Hartmann and Benveniste, 1987). Pentacyclic β-amyrin, one of the most common triterpenes in plants, and α-amyrin are present in Arabidopsis. Therefore, these two triterpenes and the three major phytosterols were analyzed together with squalene, a common precursor of triterpene and sterol. Total sterols were extracted from the rosette leaves and inflorescence of 5-week-old plants. Compared with the wild-type control, the rosette leaves of HMGR1ox (no. 15-8) showed 2 times higher β-sitosterol, 1.8 times higher campesterol and cycloartenol, 2.5 times higher β-amyrin, and 2 times higher α-amyrin contents (Fig. 6A). In inflorescence, it showed 1.6 times higher campesterol, β-sitosterol, and β-amyrin, 2.6 times higher cycloarternol, and 3.7 times higher α-amyrin (Fig. 6B) than the wild-type control. The contents of squalene and stigmasterol were not significantly changed compared with the contents of the control. To verify direct evidence of HMGR on ginsenoside biosynthesis, PgHMGR1 was constitutively overexpressed under 35S promoter in the ginseng adventitious roots that were derived from transgenic ginseng calli. The amount of individual ginsenosides in the four different transgenic lines was 1.5 to 2 times greater than the amount in the control without altering the ratio of individual ginsenoside (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of PgHMGR1 results in higher production of sterols and triterpenes. A and B, Quantification of endogenous sterols and triterpenes in Arabidopsis using GC-MS. Values represent the mean ± se of content (micrograms per gram dry weight) as calculated from three independent sterol isolations and quantification. *, Significantly different from the control at P < 0.05; **, significantly different from the control at P < 0.01. C, Relative activity of HMGR in ginseng leaves and roots. C, Quantitative analysis of major ginsenosides (ginsenosides Rg1, Re, Rf, Rb1, Rb2, Rc, and Rd) contents in control and transgenic ginseng adventitious roots of ginseng ‘Yunpoong’ overexpressing PgHMGR1 were analyzed by HPLC. Vertical bars indicate the mean ± se from three independent experiments.

Conserved Role of PgHMGR1

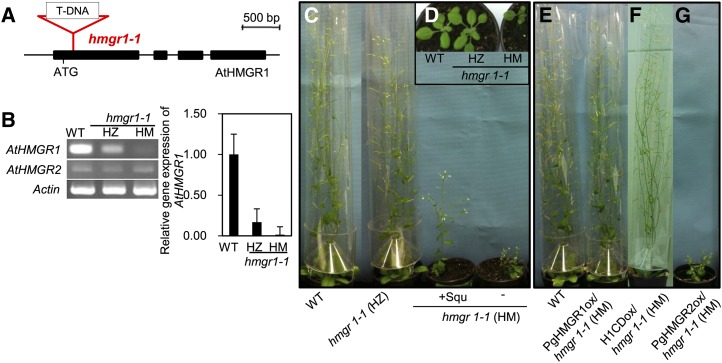

PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 showed 74.8% and 67.8% of amino acid sequence identity with AtHMGR1 (At1g76490) and AtHMGR2 (At2g17370), respectively (Enjuto et al., 1994). PgHMGR is clustered into plant HMGRs and structurally distinct from fungus and animal enzymes (Supplemental Fig. S8A). Three conserved motif sequences were identified in both plant and animal HMGRs (Supplemental Figs. S5 and S8B). The conserved role of ginseng HMGRs was revealed by the genetic complementation of Arabidopsis null mutant hmgr1-1 (Fig. 7, A, B, and D). The homozygous hmgr1-1 showed a severe dwarf phenotype with partial restoration by squalene supply (Fig. 7C). The overexpression of the full-length cDNA sequence of PgHMGR1 and the catalytic domain of PgHMGR1 under the 35S promoter complemented the phenotypic defect of hmgr1-1, whereas that of PgHMGR2 did not, indicating that PgHMGR1 is a functional ortholog of AtHMGR1 (Fig. 7, C and E to G; Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 7.

PgHMGR1 functionally complemented hmgr1-1. A, Structure of HMGR1 transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion position (SALK_125435). Black boxes indicate exons. B, Left, gene expression of the AtHMGR1 and AtHMGR2 in 3-week-old seedlings of wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HZ), and homozygous (HM) lines of hmgr1-1. The actin was used as an internal control. B, Right, Real-time qRT-PCR analysis confirmed the knockout of hmgr1-1. Data are normalized with β-actin and relative to the levels in wild-type seedlings. C and E to G, Fifty-day-old Arabidopsis plants of the wild type, hmgr1-1, and each complemented plant as indicated in the labels. PgHMGR1ox (E) and PgHMGR1CDox (F) complemented the hmgr1-1 dwarf phenotype, whereas PgHMGR2ox (G) did not. C and D, HZ hmgr1-1 shows a similar phenotype to the wild type (WT; Columbia), whereas the HM mutant shows a severe dwarf and sterile phenotype. C, Squalene treatment rescued the dwarf phenotype. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

DISCUSSION

In plants, triterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids are biosynthesized through the MVA pathway, whereas monoterpenoids, diterpenoids, and tetraterpenoids are biosynthesized through the MEP pathway. The formation of MVA is catalyzed by HMGR (Bach and Lichtenthaler, 1982), and it serves as the common precursor for the production of a number of natural products. Here, we report the whole-genome structure of two ginseng HMGR genes encompassing the promoter sequence, the subcellular localization of corresponding HMGR enzymes, and the importance of dark-regulated HMGR activity for the production of ginsenosides and sterols. In this study, ginseng plants and ginseng adventitious roots overexpressing PgHMGR as well as Arabidopsis plants heterologously overexpressing the same gene were used for the functional characterization of PgHMGR at genetic and biochemical levels (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Presumptive model of HMGR-triggered ginsenoside biosynthesis. Sterols and triterpenes produced through MVA are catalyzed by HMGR in the ER, plastid, and/or PX of the vasculature of ginseng. HMGR can be up-regulated by a light-signaling factor, PIF3, regulated by phytochrome B (phyB). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns and Developmental Roles of PgHMGRs

In contrast to the single HMGR in animals, archaea, and eubacteria, HMGR in plants is encoded by multiple HMGR genes that seem to have arisen by gene duplication and subsequent sequence divergence. In the ginseng plant, two isozymes of HMGR were identified and showed differential expression patterns with conserved structural divergences (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S3) in ginseng. Although one HMGR sequence of Panax quinquefolius (ACV65036) was reported in the National Center for Biotechnology Information to have 76% identity with the amino acid sequence of PgHMGR1, a functional study of HMGR has not yet been performed in ginseng. The transcripts of PgHMGR1 were found to be predominant in the petioles of the seedling stage and were enhanced in the roots of the 3- and 6-year-old ginseng. However, the highest expression of PgHMGR1 in the root was found at almost the same level in ginseng from the seedling stage to 3- and 6-year-old plants, whereas the transcripts of PgHMGR2 in the root were gradually increased with age (Fig. 2, B to G). It suggests that PgHMGR1 plays a major role in providing sterols or triterpenes in ginseng roots, whereas PgHMGR2 might have a more specific role in the age-dependent production of certain metabolites. Sterol biosynthesis-related genes were intended to be expressed constitutively in all plant tissues to synthesize sterol, which is necessary for plant development (He et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2006). A detailed functional understanding of sterol and triterpene in plant development needs to be further clarified. Corresponding to the expression of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 in the vasculature tissue of the roots (Fig. 2, Hb and Ib), the ginsenoside biosynthesis-related genes Pg squalene synthases (SSs) and Pg squalene epoxidases (SEs) were also characterized as being expressed in vascular bundle tissues, including phloem cells, parenchymal cells near the xylem, and resin ducts in the petioles of ginseng (Han et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2011). It can be postulated that the phloem and resin ducts might serve as metabolically active sites for sterol and saponin biosynthesis and play a role in the production of squalene oil. In fact, ginsenoside is accumulated to a greater degree in the phloem than the xylem (Fukuda et al., 2006) and is observed in parenchymal and phloem cells (Yokota et al., 2011).

The expressions of pHMGR1::GUS and pHMGR2::GUS were detected at the early postgermination stage in ginseng seedlings and also triggered during the germination stage in Arabidopsis. These results suggest that some triterpene is required for the germination stage in the seedling, which is reminiscent of the active β-amyrin production in pea seedlings (Baisted, 1971). Interestingly, PgHMGR1 was highly expressed in petiole tissue (Fig. 2B), similar to the high expression pattern of other ginsenoside biosynthesis-related genes encoding SS (Kim et al., 2011) and SE genes (Han et al., 2010). A long petiole is a distinct anatomic structure that can also be found in ginseng. The relatively high expression of PgHMGR1 in petiole may function on cell growth by producing sterols that are known as essential constituents of membranes of eukaryotic cells and/or may function on plant defense by producing derivative triterpenes. The promoter activity of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 was high in the early flowering stage, with no detection in matured silique or seed. High HMGR expression in the early developmental stage has also been shown in other plants: potato (Solanum tuberosum) HMGR1 is expressed in the early flower developmental stage (Korth et al., 1997), and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) HMGR1 is expressed in young tomato fruit (Jelesko et al., 1999). The flower phenotype in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) is altered by the overexpression of AtHMGR1 (Hey et al., 2006), which suggests that HMGR-derived phytosterols and metabolites play roles in flower development (Fig. 6B). It has also been reported that the constitutive inhibition of HMGR by Mev ultimately blocks fruit development in the early stages (Narita and Gruissem, 1989).

PgHMGR1 Contributes to Ginsenoside and Sterol Overproduction

Unfortunately, ginseng is not practically amenable to loss-of-gene or gain-of-gene function studies. To gain an insight into the effects of the loss of HMGR activity on ginsenoside biosynthesis, an inhibitor was used to deplete the metabolic flux through the MVA pathway. Treatment with Mev, a highly potent competitive inhibitor of HMGR, reduced the total ginsenoside content drastically in adventitious roots compared with the control after reduced gene expression, which is comparable with the well-known elicitor effect by MJ (Fig. 3). In adventitious roots, the increment of MJ-induced ginsenosides is almost correlated with the expression level of PgHMGR1, whereas PgHMGR2 seems to be working independently or rather, inhibitory to the action of PgHMGR1 in a certain stage. Here, the possible posttranscriptional modification also needs to be considered, and it will explain the gaps between expression and activity for the ginsenoside production. The apparent Mev-induced HMGR activity (Fig. 3C) can be explained by the increased translation or decreased degradation of the proteins through the feedback regulatory mechanism (Hemmerlin et al., 2003). Importantly, overexpressing PgHMGR1 in ginseng adventitious roots actually resulted in increased ginsenosides contents (Fig. 6C).

In addition, to test whether PgHMGR1 can contribute to the triterpene pathway in other plants, PgHMGR1 was further expressed in Arabidopsis. Although HMGR is known as the key regulatory enzyme of sterol biosynthesis in plants (Babiychuk et al., 2008), overexpression of HMGR in Arabidopsis did not show any altered morphology or isoprenoid content (Re et al., 1995). However, overexpression of the Hevea brasiliensis HMGR in tobacco increased the amount of sterol and mainly, the intermediates of the sterol pathway in the form of fatty acyl esters in accordance with the increased activity of HMGR (Chappell, 1995; Schaller et al., 1995). Sterol-enriched tomato mutant also showed greater accumulation of biosynthetic intermediates that were esterified with fatty acids and stored in cytoplasmic lipid droplets (Maillot-Vernier et al., 1991). In the case of the overexpression in tomato, phytosterols were elevated without altering the activity of HMGR (Enfissi et al., 2005). The constitutive overexpression of PgHMGR1 driven by the 35S promoter resulted in the accumulation of not only sterols but also, triterpenes in Arabidopsis (Fig. 6, A and B), with a modest increase of HMGR activity. Based on the previous reports, it should also be noted that the major type of sterols in PgHMGR1ox lines are esterified.

Tight Regulation of HMGR Activity by Dark Contributes to Ginsenoside Biosynthesis

Plant HMGR is modulated by myriad cellular and environmental signals, such as plant hormones, calcium, chemical challenge, pathogen, wounding, and especially, light (Stermer et al., 1994). The dark-induced expression of HMGR1 promoter activity in Arabidopsis immature leaves and seedlings (Learned and Connolly, 1997) as well as increased HMGR activity in etiolated pea seedlings (Brooker and Russell, 1979) are in direct contrast to the suppression of HMGR activity in dark-treated mature green potato plants (Korth et al., 2000). In the case of ginseng HMGR, the dark treatment induced the promoter activity of PgHMGR in etiolated hypocotyl (Fig. 4G), which was reversed in the true leaves of pHMGR1::GUS Arabidopsis (Fig. 4H). Reduced transcripts of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were also observed in the ginseng plant (Fig. 4D). The differential regulation of the pHMGR1::GUS expression in leaf and hypocotyl tissue can be explained by an organ-autonomous response (Learned and Connolly, 1997). Down-regulation of HMGR in Arabidopsis because of light was shown to occur through photoreceptor phytochrome B and transcription factor LONG HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5; Rodríguez-Concepción et al., 2004). Analysis of the promoter sequence implied that PgHMGR1 might be regulated by PIF3 binding to the G box in the region of PgHMGR1 promoter (Fig. 4F), which requires further confirmation by experimental analysis. PIFs, basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, play a central role in the light-mediated responses (Castillon et al., 2007). Shin et al. (2007) showed that PIF3 and HY5 regulate the anthocyanin biosynthesis by binding to the promoters of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes. PIF3 is also known as a negative component in the phytochrome B-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation (Kim et al., 2003). Taken together, it suggests that ginsenoside biosynthesis is tightly regulated by light, possibly through PIF3-mediated regulation. When the whole ginseng plant was kept in the dark for up to 48 h, the ginsenoside content increased 24% in leaf and 35% in root compared with the control (Fig. 4, A and B). This result might also be because of the dark stress by the light-to-dark switch (Souret et al., 2003). The contents of naturally synthesizing ginsenosides and the ratio of protopanaxatriol-protopanaxadiol types of ginsenosides are different between species and organs (Wang et al., 1999; Qu et al., 2009). The differential regulation of PgHMGR genes in leaf and root by the dark can be a good starting point to explain the differential ginsenoside biosynthesis. In mature ginseng leaf, both PgHMGR genes are coordinately down-regulated (Fig. 4D). However, the gene expression of PgHMGR2 in root behaves in different ways in initial stages of the treatment (Figs. 3B and 4E). In 3- and 6-year-old roots, where the expression patterns of PgHMGR1 are constant and PgHMGR2 is differentially up-regulated with perfect age matches with these differential transcriptional regulations (Fig. 2). Thus, we speculate that PgHMGR1 plays general housekeeping roles, whereas PgHMGR2 plays stress- and time-dependent specific roles, which still need to be clarified. However, dark-induced HMGR activity in the ginseng plant for 2 to 3 d was positively correlated with the total ginsenoside content (Fig. 4, A and C).

PgHMGR1 Localized into the Cytoplasmic Organelles and Its Gene Complements AtHMGR1

Both PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 contain an RRR motif at their N terminus, which may act as an ER retention signal (Schutze et al., 1994; Merret et al., 2007). When PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were expressed individually in Arabidopsis as C-terminal CFP fusions, both proteins were also targeted to the ER and vesicle-like structures and merged with the ER, PX, and plastid markers (Nelson et al., 2007; Fig. 5). It suggests that ginseng HMGR could be targeted to different subcellular organelles through posttranslational modifications. We cannot exclude the possibility of alternative mRNA processing, which might contribute to a differential localization. For example, the long isoform of IPP isomerase was targeted to the chloroplast and mitochondria, whereas its short isoform was localized to the peroxisome (Sapir-Mir et al., 2008). The catalytic domain of ginseng HMGR was localized to the cytosol, confirming that the N-terminal domain of PgHMGR is necessary for binding to the membrane, supporting a previous report (Leivar et al., 2005). In mammals, the peroxisomal localization of HMGR in rat (Keller et al., 1985) was reported in addition to ER localization (Goldfarb, 1972); thus, dual localization of HMGR in the PX and ER needs to be considered (Kovacs et al., 2007). The localization of PgHMGR1 in multiple subcellular compartments may play roles in the specialized localization of ginsenoside Rb1 in the cytosol, plastid, and PX in the ginseng plant (Yokota et al., 2011). The plastidial MEP pathway can also contribute to the localization of ginsenosides in distinct compartments. Here, the possible cross talk between the MVA and MEP pathways may also be involved (Hemmerlin et al., 2003).

Although PgHMGR1 was expressed in different levels among the tested organs, the PgHMGR1 gene seems to be expressed constitutively throughout ginseng development, which was similar to the characterized homologs from Salvia miltiorrhiza (Liao et al., 2009) and Eucommia ulmoides (Jiang et al., 2006). Indeed, the heterologous expression of the two full-length ginseng HMGRs in the Arabidopsis hmgr1-1 mutant background showed that only PgHMGR1 could complement the dwarf and sterile phenotypes of hmgr1-1 (Suzuki et al., 2004), which suggests that PgHMGR1 is a functional ortholog of AtHMGR1. The defect of AtHMGR1 could also be complemented by the catalytic domain of PgHMGR1, suggesting that the product of PgHMGR1 is sufficient to complement without proper targeting to an organelle. Although PgHMGR1 shares more identity with AtHMGR1 than with AtHMGR2, it has the closest relationship with EsHMGR, HMGR in Eleutherococcus senticosus, which is a small and woody shrub of the same family known to have similar herbal properties as ginseng (Huang et al., 2011). PgHMGR2 shares a high sequence identity with HMGR2 (CaHMGR and AAB69727) from Camptotheca acuminata (Maldonado-Mendoza et al., 1997), which also showed lower expression than HMGR1. This result suggests that PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 originated from a gene evolution event after the split from Arabidopsis and before the separation of PgHMGR1 and its homologs. Considering these findings, it is possible that each of the isozymes of HMGR could have evolved separately according to the production of specific products rather than by duplication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The Columbia ecotype (CS60000) of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was used as a model plant in this study. ER-YFP-expressing lines (ER-yk; CS16251), PX-YFP-expressing lines (PX-yk; CS16261), MT-YFP-expressing lines (MT-yk; CS16264), and PT-YFP-expressing lines (PT-yk; CS16267; Nelson et al., 2007) and hmgr1-1 (SALK_125435) were purchased from the Arabidopsis Stock Center (http://www.Arabidopsis.org/). Seeds were surface sterilized and sown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (Duchefa Biocheme) containing 1% (w/v) Suc, 0.5 g/L 2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulphonic acid (pH 5.7) with KOH, and 0.8% (w/v) agar. Three-day cold-treated seeds were germinated under a long-day condition of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark at 23°C. The Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng ‘Yunpoong’) seeds used in this study were obtained from the Ginseng Bank in South Korea. Transformants were selected on hygromycin-containing plates (50 µg/mL). Ten-day-old seedlings were transplanted into soil and allowed to grow for up to 5 weeks under the same light and dark conditions. For RNA extraction, seedlings were grown on plates for 15 d. For metabolite analysis, leaves and the inflorescence from 5-week-old plants were collected.

Ginseng Materials and Treatment

Mev and MJ were purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions of Mev (10 mm) and MJ (100 mm) in ethanol were stored at −20°C. For inhibitor treatment of ginseng adventitious roots, after 4 weeks of precultivation, 10 µm Mev or 10 µm MJ was added. After 1, 3, and 7 d, harvested adventitious roots were frozen and used for RNA extraction, HMGR activity assay, and ginsenoside analysis. Three-year-old ginseng plants were hydroponically grown in perlite and peat moss at 23°C ± 2°C under white fluorescent light (60–100 µmol m−2 s−1) in a controlled greenhouse (provided by i-farm, Yeo-Ju, Korea) and used for dark treatment. Control plants were grown in 16 h of light and 8 h of dark and sampled in light conditions, whereas dark treatments (covered with a black box) lasted for 2 and 3 d. Leaf and root parts were separately used for RNA isolation, HMGR activity assay, and ginsenoside analysis.

Identification of PgHMGR Genes and Sequence Analysis

To obtain a full-length coding sequence of the PgHMGR gene, RACE PCR was performed using a Capfishing full-length cDNA premix kit (Seegene) and HotStarTaq (Qiagen) as a DNA polymerase. The first strand cDNA synthetic reaction from total RNA was catalyzed by superscript III RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the cDNA was prepared using a commercial cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech). Specific primers were designed according to the 3′-end and 5′-end sequences of partial PgHMGR ESTs, which were derived from our ginseng EST library. The primer sequences used were as follows: for HMGR1, HMG_F2, 5′-ATG GAG GCC ATT AAC GAT GGA AAA G-3′; HMG_R2, 5′-ACC AAC CTC AAT TGA TGG CAT TGT G-3′; HMG_R3, 5′-CCT TTT TGC CGT AGA AAA CCT AAC CA-3′; and for HMGR2, HMG2_F2, 5′-TAC TCA CTC GAG TCC AAA CTG GGA GAC-3′; HMG2_R1, 5′-GGC ATG CTA ATT GGG TCC CAC CTC CT-3′; HMG2_R3, 5′-ATT GCC TCA CAA ACA ACC GAT TTA CC-3′. RACE PCR was performed by the hot-start method with the following conditions: 30 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 60 cycles at 66°C for 40 s, 72°C for 80 s, and a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product was purified and ligated into a pGEM-T vector (Promega) followed by sequencing. By assembling the sequence of the 3′-RACE and 5′-RACE products, the full-length cDNA sequence of PgHMGRs was deduced. Sixty nanograms of genomic DNA of cv Yunpoong and a pair of PCR primers (start codon and stop codon) were used for amplifying the genomic sequence of PgHMGR. Deduced amino acid sequences were searched for homologous proteins using the BLASTX databases. ClustalX with default gap penalties was used to perform multiple alignments. A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method, and the reliability of each node was established by bootstrap methods using MEGA4 software. Identification of the conserved motifs of HMGR was accomplished with Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation.

Isolation of Promoter Sequences

The Universal Genome Walker Kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) was used to isolate fragments of the PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 promoter. Ten 6-bp recognizing and blunt end-forming restriction enzymes (DraI, EcoRV, PvuII, StuI, SspI, SmaI, MscI, ScaI, Eco105I, and HpaI) were used to digest the isolated cv Yunpoong genomic DNA. DNA fragments containing the adaptors at both ends were used as templates for amplifying the PgHMGR promoter regions. The first PCR, using adaptor primer (AP1) and gene-specific primer (GSP) (H1-GSP1, 5′-ATA ACA GTC CCC GAG TTT TGA TTC CAG-3′; H2-GSP1, 5′-GCT TGG GAG GAA GAG AAC AGT CGA TAG C-3′), and the second nested PCR, using AP2 and H1_GSP2 and H2_GSP2 (H1_GSP2, 5′-ACG TGA GAC AAA TGA TTG GAC GAA ATC-3′; H2_GSP2, 5′-ATG GCT CTC GAC GAC TAT CTT CCT CGT T-3′), were performed using i-MAXII (Intron). The amplified fragment was cloned in the pGEM-T vector and sequenced. The promoters were analyzed using PlantPan (Plant Promoter Analysis Navigator).

Vector Construction and Arabidopsis Transformation

To visualize the subcellular localization patterns of ginseng HMGRs, cDNA sequences of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 were cloned into a pCAMBIA1390 vector containing the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S promoter and enhanced CFP (eCFP). The PgHMGR1 cDNA and its catalytic domain (PgHMGR1CD; amino acid residues 154–573) were amplified using primers with XhoI and EcoRI sites (underlined; PgHMGR1, 5′-TA CTC GAG ATG GAC GTC CGC CGG AGA-3′ and 5′-TG GAA TTC AGA TCC AAT TTT GGA CAT-3′; PgHMGR1CD, 5′-TA CTC GAG ATG CCC GTA GTG ATG TCA-3′ and 5′-TG GAA TTC AGA TCC AAT TTT GGA CAT-3′). The PgHMGR2 cDNA was amplified using primers with SalI and AvrII sites (underlined): 5′-CA GTC GAC ATG GAC GTT CGC CGG CGA CCT-3′ and 5′-GA CCT AGG CTA GGA GGA GAG TTT TGT-3′. Enzyme-digested PCR products were cloned into the PLA2a gene site of Pro-35S:PLA2a-eCFP/pCAMBIA1390 (Lee et al., 2010) as eCFP fusion proteins (Pro-35S:PgHMGR1-eCFP, Pro-35S:PgHMGR1CD-eCFP, or Pro-35S:PgHMGR2-eCFP). To express the PgHMGR1 fusion protein with mRFP at the C terminus, the mRFP was amplified from 326-mRFP using primers with EcoRI and SpeI sites (5′-TG GAA TTC ATG GCC TCC TCC GAG GAC-3′ and 5′-GG ACT AGT TTA GGC GCC GGT GGA GTG-3′) and replaced with eCFP of Pro-35S:PgHMGR1-eCFP. The 1,317 and 477 nucleotides of genomic PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2 DNA, respectively, were amplified with HindIII and BamHI sites (Pro-PgHMGR1, 5′-TG AAG CTT AGC TAA AGA AAG TTA GGC-3′ and 5′-TA GGA TCC GGA AGA GTA TAT TCC GGC-3′; Pro-PgHMGR2, 5′-CG AAG CTT GTA ATG TGT TCC CAC TTC CAT-3′ and 5′-TA GGA TCC CTT TAT GGT GGG GGA ACT CCG-3′) and cloned to a pCambia 1390 vector containing the GUS gene. All transgene constructs were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing before plant transformation. The constructs were transformed into Arabidopsis using Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pMP90; Bechtold and Pelletier, 1998). The insertion of transgenes into the transformants was confirmed by confocal microscopy or PCR. Homozygous plants with a 3:1 segregation ratio on antibiotic plates were selected for additional analyses. For each construct, 20 to 50 T1-independent lines were obtained, and the phenotypic significance of the transgenes was analyzed for the chosen lines.

Transformation of Ginseng

Zygotic embryos of ginseng ‘Yunpoong’ seeds (provided by Ginseng Genetic Resource Bank) were stratified in humidified sand to mature for 3 months at 5°C. After stratification, the seeds, in which zygotic embryos were in a mature state (4 mm in length), were immersed in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 1 min, surface sterilized in 2% (v/v) NaOCl for 15 min, and rinsed three times with sterilized distilled water. After carefully dissecting the zygotic embryos, they were placed on Murashige and Skoog basal medium containing 3% (w/v) Suc and 0.8% (w/v) agar. Five-day-old zygotic embryos were excised transversely, and cotyledon explants (4 mm) were used for transformation. The explants were dipped in the bacterial solution for 15 min, subsequently blotted with sterile filter paper, and cocultivated with A. tumefaciens C58C1 on Murashige and Skoog medium containing 3% (w/v) Suc and 1 µg/mL 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid for 2 d. Thereafter, the explants were cultured on selection Murashige and Skoog medium with 3% (w/v) Suc, 1 µg/mL 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, 0.5 µg/mL 6-benzylaminopurine, 250 µg/mL cefotaxime, and 50 µg/mL hygromycin. After subculturing six times every 2 weeks on selection medium, the surviving cotyledons producing calli were cultured on the same medium without antibiotics, and adventitious roots were induced from calli on B5 medium with 3% (w/v) Suc and 3 mg/L indole-3-butyric acid. More than 10 transgenic lines were generated, and adventitious roots were excised from the maternal explants before subculturing in liquid B5 medium with 3% (w/v) Suc and 2 mg/L indole-3-butyric acid, which was replaced every 5 weeks.

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from frozen samples with the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen), including the DNase I digestion step. Next, 2 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with RevertAid H Minus M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Fermentas). qRT-PCR was performed in a 25-µL reaction volume consisting of 0.2 µLof cDNA product and 5 pmol of each primer using Super-Taq DNA polymerase (Super Bio) by a Bio-Rad PCR machine (3 min at 95°C followed by 28 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min). The products were analyzed on 1.2% (w/v) agarose gels. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using 100 ng of cDNA in a 10-µL reaction volume using SYBR Green Sensimix Plus Master Mix (Quantace). The following thermal cycler conditions recommended by the manufacturer were used: 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 20 s. The fluorescent product was detected during the final step of each cycle. Amplification, detection, and data analysis were carried out on a Rotor-Gene 6000 real-time rotary analyzer (Corbett Life Science). To determine the relative fold differences in template abundance for each sample, the threshold cycle (Ct) value for each of the gene-specific genes was normalized to the Ct value for β-actin and calculated relative to a calibrator using the algorithm 2−ΔCt or 2−ΔΔCt. Three independent experiments were performed, and the primer efficiencies were determined according to the method by Livak and Schmittgen (2001) to validate the ΔΔCt method. The observed slopes were close to zero, indicating that the efficiencies of the gene and the internal control β-actin were equal.

Confocal Microscopy Analysis

The fluorescence from reporter proteins and organelle markers was observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss). GFP, CFP, YFP, and mRFP were detected using 488-/505- to 530-, 458-/475- to 525-, 514-/>530-, and 543-/560- to 615-nm excitation/emission filter sets, respectively. Fluorescence images were digitized with the Zeiss LSM image browser.

HMGR Activity Assay

Extraction of crude proteins was performed as described (Rodríguez-Concepción et al., 2004), with minor modifications. Two-week-old seedlings of Arabidopsis, leaves or roots of 3-year-old ginseng, or adventitious roots of ginseng (approximately 200 mg) were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 1 mL of prechilled extraction buffer containing 100 mm Suc, 40 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 30 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaCl, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, 1 µm bestatin, 15 µm E64, 20 µm leupeptin, 15 µm pepstatin, 0.5 mm phenanthroline, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.25% (w/v) Triton X-100. The slurry was centrifuged at 200g and 4°C for 10 min to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was then used for the determination of HMGR activity as previously described (Dale et al., 1995) with the following modifications. The protein concentration was determined with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Intron). The supernatant was analyzed using a spectrophotometric assay at 37°C (total volume of 200 µL) containing 0.3 mm HMG-CoA, 0.2 mm NADPH, and 4 mm dithiothreitol in 50 mm Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.0). The decrease in A340 was monitored for 20 min after the addition of HMG-CoA. One unit of HMGR activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that oxidizes 1 µmol NADPH min−1 at 37°C.

GUS Histochemical Analysis

Four-day-old seedlings were treated with the indicated chemical for 3 h before visualizing the GUS activity. GUS staining was performed by incubating whole seedlings in the staining buffer containing 1 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d-GlcA cyclohexylammonium salt (Duchefa Biocheme), 0.1 m NaH2PO4, 0.1% (w/v) Triton-X, and 0.5 mm potassium ferricyanide and ferrocyanide at 37°C until a blue color appeared (1–3 h). Stained seedlings were cleared in 70% (v/v) ethanol and then 100% (v/v) ethanol for 2 h each. In the final step of dehydration, samples were sequentially exposed to 10% (v/v) glycerol/50% (v/v) ethanol and 30% (v/v) glycerol/30% (v/v) ethanol. Seedlings were photographed under a microscope (ZEISS Axio Observer D1).

HPLC Analysis of Ginsenosides Extracted from Ginseng

For the analysis of ginsenosides from different ginseng samples, 0.3 to 1 g of milled powder of freeze-dried adventitious roots, leaves, and roots was soaked in 80% (v/v) MeOH at 70°C. After evaporation, the residue was dissolved in water, followed by extraction with water-saturated n-butanol. The butanol layer was then evaporated to produce the saponin fraction. Each sample was dissolved in MeOH (1 g/5 mL), filtered through a 0.45-µm filter, and used for HPLC analysis. The HPLC separation was carried out on an Agilent 1260 series HPLC system. This experiment used a C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, i.d. = 5 µm) column using acetonitrile (solvent A) and distilled water (solvent B) mobile phases, with a flow rate of 1.6 mL/min and the following gradient: A:B ratios of 80.5:19.5 for 0 to 29 min, 70:30 for 29 to 36 min, 68:32 for 36 to 45 min, 66:34 for 45 to 47 min, 64.5:35.5 for 47 to 49 min, 0:100 for 49 to 61 min, and 80.5:19.5 for 61 to 66 min. The sample was detected by UV spectrometry at a wavelength of 203 nm. Quantitative analysis was performed with a one-point curve method using external standards of authentic ginsenosides.

GC-MS Analysis of Sterols and Triterpenes Extracted from Arabidopsis

Using the method modified from Suzuki et al. (2004), freeze-dried plant materials (rosette leaves, 200 mg; inflorescence, 25 mg) were powdered and then extracted two times with 1 mL of CHCl3:MeOH (7:3) at room temperature. 5-α-Cholestane (20 µg) was used as an internal standard. The extract was dried in a rotary evaporator and saponified with 1.5 mL each of MeOH and 20% (v/v) KOH aqueous for 1 h at 80°C to hydrolyze the sterol esters. After saponification, 1.5 mL each of MeOH and 4 n HCl were added for 1 h at 80°C, and these reaction mixtures were extracted three times with 4 mL of hexane. When the phases separated, the sterols partitioned to the hexane layer, and the combined hexane layer was evaporated to dryness. The residue was trimethylsilylated with pyridine and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide + 1% trimethyl chlorosilane (1:1) at 37°C for 90 min and then analyzed by capillary GC-MS. GC-MS analysis was performed using a mass spectrometer (HP 5973 MSD) connected to a gas chromatograph (6890A; Agilent Technologies) with a DB-5 (MS) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness). The analytical conditions were as follows: electron ionization, 70 eV; source temperature, 250°C; injection temperature, 250°C; column temperature program of 80°C for 1 min, then increased to 280°C at a rate of 10°C/min and held at this temperature for 17 min; posttemperature, 300°C; carrier gas, He; flow rate, 1 mL/min; run time, 38 min; and splitless injection. The endogenous sterol levels were determined as the peak area ratios of molecular ions of the endogenous sterol and internal standard. Standards, including squalene, phytosterols (campesterol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol), and triterpene (β-amyrin and α-amyrin) were purchased from Sigma.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. PgHMGR1 sequence.

Supplemental Figure S2. PgHMGR2 sequence.

Supplemental Figure S3. DNA structures of PgHMGR1 and PgHMGR2.

Supplemental Figure S4. Motif analysis of HMGRs.

Supplemental Figure S5. Multiple alignments of HMGRs.

Supplemental Figure S6. Ginsenoside contents by inhibitor and activator.

Supplemental Figure S7. Ginsenoside contents by dark treatment.

Supplemental Figure S8. Structural features of PgHMGR1.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tae-Jin Yang (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) for providing the genomic DNA sequence of ginseng, i-farm (Yeo-Ju, Korea) for providing the ginseng samples, and Dabing Zhang (Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China) for critical reading and comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ER-yk

endoplasmic reticulum marker

- GC-MS

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- HMGR

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- MEP

methylerythritol phosphate

- Mev

mevinolin

- MJ

methyl jasmonate

- mRFP

monomeric red fluorescent protein

- MVA

mevalonate

- PIF

phytochrome-interacting factor

- PgHMGR

ginseng 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase

- PT-yk

plastid marker

- PX-yk

peroxisome marker

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

- SE

squalene epoxidase

- SS

squalene synthase

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- MS

Murashige and Skoog medium

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (SSAC; grant no. PJ00952902 to O.R.L.), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea, and iPET (grant no. 112142-05-1-CG000 to D.-C.Y.), Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Abdin MZ, Kiran U, Aquil S. (2012) Molecular cloning and structural characterization of HMG-CoA reductase gene from Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Donn. cv. Albus. Indian J Biotechnol 11: 16–22 [Google Scholar]

- Alam P, Abdin MZ. (2011) Over-expression of HMG-CoA reductase and amorpha-4,11-diene synthase genes in Artemisia annua L. and its influence on artemisinin content. Plant Cell Rep 30: 1919–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attele AS, Zhou YP, Xie JT, Wu JA, Zhang L, Dey L, Pugh W, Rue PA, Polonsky KS, Yuan CS. (2002) Antidiabetic effects of Panax ginseng berry extract and the identification of an effective component. Diabetes 51: 1851–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin JM, Kuzina V, Andersen SB, Bak S. (2011) Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry 72: 435–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiychuk E, Bouvier-Navé P, Compagnon V, Suzuki M, Muranaka T, Van Montagu M, Kushnir S, Schaller H. (2008) Allelic mutant series reveal distinct functions for Arabidopsis cycloartenol synthase 1 in cell viability and plastid biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3163–3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach TJ, Lichtenthaler HK. (1982) Mevinolin: a highly specific inhibitor of microsomal 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase of radish plants. Z Naturforsch C 37: 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach TJ. (1986) Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in phytosterol synthesis? Lipids 21: 82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach TJ, Lichtenthaler HK. (1987) Plant growth regulation by mevinolin and other sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. In Fuller G, Nes WD, eds, Ecology and Metabolism of Plant Lipids. American Chemical Society Symposium Series, Vol 325 American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp 109–139 [Google Scholar]

- Bach TJ, Weber T, Motel A. (1990) Some properties of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis and metabolism of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA in plants. Recent Adv Phytochem 24: 1–82 [Google Scholar]

- Baisted DJ. (1971) Sterol and triterpene synthesis in the developing and germinating pea seed. Biochem J 124: 375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Pelletier G. (1998) In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. In Martinez-Zapater JM, Salinas J, eds, Arabidopsis Protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker JD, Russell DW. (1975) Subcellular localization of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase in Pisum sativum seedlings. Arch Biochem Biophys 167: 730–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker JD, Russell DW. (1979) Regulation of microsomal 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from pea seedlings: rapid posttranslational phytochrome-mediated decrease in activity and in vivo regulation by isoprenoid products. Arch Biochem Biophys 198: 323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos N, Boronat A. (1995) Targeting and topology in the membrane of plant 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. Plant Cell 7: 2163–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillon A, Shen H, Huq E. (2007) Phytochrome interacting factors: central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci 12: 514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell J. (1995) Biochemistry and molecular biology of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 46: 521–547 [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Shen LH, Zhang JT. (2005) Anti-amnestic and anti-aging effects of ginsenoside Rg1 and Rb1 and its mechanism of action. Acta Pharmacol Sin 26: 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale S, Arró M, Becerra B, Morrice NG, Boronat A, Hardie DG, Ferrer A. (1995) Bacterial expression of the catalytic domain of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (isoform HMGR1) from Arabidopsis thaliana, and its inactivation by phosphorylation at Ser577 by Brassica oleracea 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase kinase. Eur J Biochem 233: 506–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enfissi EM, Fraser PD, Lois LM, Boronat A, Schuch W, Bramley PM. (2005) Metabolic engineering of the mevalonate and non-mevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate-forming pathways for the production of health-promoting isoprenoids in tomato. Plant Biotechnol J 3: 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjuto M, Balcells L, Campos N, Caelles C, Arró M, Boronat A. (1994) Arabidopsis thaliana contains two differentially expressed 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase genes, which encode microsomal forms of the enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 927–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N, Shan S, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. (2006) New staining methodology: Eastern blotting for glycosides in the field of Kampo medicines. J Nat Med 60: 21–27 [Google Scholar]

- Fuzzati N. (2004) Analysis methods of ginsenosides. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 812: 119–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis CN. (1997) Panax ginseng pharmacology: a nitric oxide link? Biochem Pharmacol 54: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb S. (1972) Submicrosomal localization of hepatic 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a (HMG-CoA) reductase. FEBS Lett 24: 153–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Brown MS. (1990) Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature 343: 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Hwang HS, Choi SW, Kim HJ, Choi YE. (2012) Cytochrome P450 CYP716A53v2 catalyzes the formation of protopanaxatriol from protopanaxadiol during ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Physiol 53: 1535–1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, In JG, Kwon YS, Choi YE. (2010) Regulation of ginsenoside and phytosterol biosynthesis by RNA interferences of squalene epoxidase gene in Panax ginseng. Phytochemistry 71: 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Kim HJ, Kwon YS, Choi YE. (2011) The Cyt P450 enzyme CYP716A47 catalyzes the formation of protopanaxadiol from dammarenediol-II during ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 2062–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Kwon YS, Yang DC, Jung YR, Choi YE. (2006) Expression and RNA interference-induced silencing of the dammarenediol synthase gene in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1653–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann MA, Benveniste P. (1987) Plant membrane sterols: isolation, identification, and biosynthesis. Methods Enzymol 148: 632–650 [Google Scholar]

- He JX, Fujioka SH, Li TCH, Kang SG, Seto H, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Jang JC. (2003) Sterols regulate development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 131: 1258–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerlin A, Hoeffler JF, Meyer O, Tritsch D, Kagan IA, Grosdemange-Billiard C, Rohmer M, Bach TJ. (2003) Cross-talk between the cytosolic mevalonate and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathways in tobacco bright yellow-2 cells. J Biol Chem 278: 26666–26676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey SJ, Powers SJ, Beale MH, Hawkins ND, Ward JL, Halford NG. (2006) Enhanced seed phytosterol accumulation through expression of a modified HMG-CoA reductase. Plant Biotechnol J 4: 219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostettmann K, Marston A. (1995) Saponins. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Zhao H, Huang B, Zheng C, Peng W, Qin L. (2011) Acanthopanax senticosus: review of botany, chemistry and pharmacology. Pharmazie 66: 83–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelesko JG, Jenkins SM, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Gruissem W. (1999) Regulation of tomato HMG1 during cell proliferation and growth. Planta 208: 310–318 [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Kai G, Cao X, Chen F, He D, Liu Q. (2006) Molecular cloning of a HMG-CoA reductase gene from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Biosci Rep 26: 171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller GA, Barton MC, Shapiro DJ, Singer SJ. (1985) 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase is present in peroxisomes in normal rat liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 770–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Yi H, Choi G, Shin B, Song PS, Choi G. (2003) Functional characterization of phytochrome interacting factor 3 in phytochrome-mediated light signal transduction. Plant Cell 15: 2399–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Lee BS, In JG, Sun H, Yoon JH, Yang DC. (2006) Comparative analysis of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) of ginseng leaf. Plant Cell Rep 25: 599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MW, Ko SR, Choi KJ, Kim SC. (1987) Distribution of saponin in various sections of Panax ginseng root and changes of its contents according to root age. Korean J Ginseng Res 11: 10–16 [Google Scholar]

- Kim OT, Bang KH, Jung SJ, Kim YC, Hyun DY, Kim SH, Cha SW. (2010) Molecular characterization of ginseng farnesyldiphosphate synthase gene and its up-regulation by methyl jasmonate. Biol Plant 54: 47–53 [Google Scholar]

- Kim TD, Han JY, Huh GH, Choi YE. (2011) Expression and functional characterization of three squalene synthase genes associated with saponin biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 125–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa I, Taniyama T, Shibuya H, Noda T, Yoshikawa M. (1987) Chemical studies on crude drug processing. V. On the constituents of ginseng radix rubra (2): comparison of the constituents of white ginseng and red ginseng prepared from the same Panax ginseng root. Yakugaku Zasshi 107: 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth KL, Jaggard DAW, Dixon RA. (2000) Developmental and light-regulated post-translational control of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase levels in potato. Plant J 23: 507–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth KL, Stermer BA, Bhattacharyya MK, Dixon RA. (1997) HMG-CoA reductase gene families that differentially accumulate transcripts in potato tubers are developmentally expressed in floral tissues. Plant Mol Biol 33: 545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs WJ, Tape KN, Shackelford JE, Duan X, Kasumov T, Kelleher JK, Brunengraber H, Krisans SK. (2007) Localization of the pre-squalene segment of the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in mammalian peroxisomes. Histochem Cell Biol 127: 273–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushiro T, Shibuya M, Ebizuka Y. (1998) β-amyrin synthase—cloning of oxidosqualene cyclase that catalyzes the formation of the most popular triterpene among higher plants. Eur J Biochem 256: 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learned RM, Connolly EL. (1997) Light modulates the spatial patterns of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 11: 499–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Jeong JH, Seo JW, Shin CG, Kim YS, In JG, Yang DC, Yi JS, Choi YE. (2004) Enhanced triterpene and phytosterol biosynthesis in Panax ginseng overexpressing squalene synthase gene. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 976–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee OR, Kim SJ, Kim HJ, Hong JK, Ryu SB, Lee SH, Ganguly A, Cho HT. (2010) Phospholipase A2 is required for PIN-FORMED protein trafficking to the plasma membrane in the Arabidopsis root. Plant Cell 22: 1812–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, González VM, Castel S, Trelease RN, López-Iglesias C, Arró M, Boronat A, Campos N, Ferrer A, Fernàndez-Busquets X. (2005) Subcellular localization of Arabidopsis 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. Plant Physiol 137: 57–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao JK, Laufs U. (2005) Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 89–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P, Zhou W, Zhang L, Wang J, Yan X, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Li L, Zhou G, Kai G. (2009) Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of a new gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Physiol Plant 31: 565–572 [Google Scholar]

- Liu WK, Xu SX, Che CT. (2000) Anti-proliferative effect of ginseng saponins on human prostate cancer cell line. Life Sci 67: 1297–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta CT) method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü JM, Yao Q, Chen C. (2009) Ginseng compounds: an update on their molecular mechanisms and medical applications. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 7: 293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbreras V, Campos N, Boronat A. (1995) The use of an alternative promoter in the Arabidopsis thaliana HMG1 gene generates an mRNA that encodes a novel 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase isoform with an extended N-terminal region. Plant J 8: 541–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillot-Vernier P, Gondet L, Schaller H, Benveniste P, Belliard G. (1991) Genetic study and further biochemical characterization of a tobacco mutant that overproduces sterols. Mol Gen Genet 231: 33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Mendoza IE, Vincent RM, Nessler CL. (1997) Molecular characterization of three differentially expressed members of the Camptotheca acuminata 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGR) gene family. Plant Mol Biol 34: 781–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merret R, Cirioni J, Bach TJ, Hemmerlin A. (2007) A serine involved in actin-dependent subcellular localization of a stress-induced tobacco BY-2 hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase isoform. FEBS Lett 581: 5295–5299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki M, Yoo YC, Matsuzawa K, Sato K, Saiki I, Tono-oka S, Samukawa K, Azuma I. (1995) Inhibitory effect of tumor metastasis in mice by saponins, ginsenoside-Rb2, 20(R)- and 20(S)-ginsenoside-Rg3, of red ginseng. Biol Pharm Bull 18: 1197–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S, Uchiyama Y, Yoshida K, Mizukawa H, Haruki E. (1998) The effects of ginseng radix rubra on human vascular endothelial cells. Am J Chin Med 26: 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita JO, Gruissem W. (1989) Tomato hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase is required early in fruit development but not during ripening. Plant Cell 1: 181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A. (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Suzuki M, Masuda K, Yoshida S, Muranaka T. (2007) Chemical phenotypes of the hmg1 and hmg2 mutants of Arabidopsis demonstrate the in-planta role of HMG-CoA reductase in triterpene biosynthesis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 55: 1518–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JD. (1996) Recent studies on the chemical constitutes of Korean ginseng. Korean J Ginseng Sci 20: 389–415 [Google Scholar]

- Qu C, Bai Y, Jin X, Wang Y, Zhang K, You J, Zhang H. (2009) Study on ginsenosides in different parts and ages of Panax quinquefolius L. Food Chem 115: 340–346 [Google Scholar]

- Radad K, Gille G, Liu L, Rausch WD. (2006) Use of ginseng in medicine with emphasis on neurodegenerative disorders. J Pharmacol Sci 100: 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re EB, Jones D, Learned RM. (1995) Co-expression of native and introduced genes reveals cryptic regulation of HMG CoA reductase expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J 7: 771–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Concepción M, Forés O, Martinez-García JF, González V, Phillips MA, Ferrer A, Boronat A. (2004) Distinct light-mediated pathways regulate the biosynthesis and exchange of isoprenoid precursors during Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant Cell 16: 144–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir-Mir M, Mett A, Belausov E, Tal-Meshulam S, Frydman A, Gidoni D, Eyal Y. (2008) Peroxisomal localization of Arabidopsis isopentenyl diphosphate isomerases suggests that part of the plant isoprenoid mevalonic acid pathway is compartmentalized to peroxisomes. Plant Physiol 148: 1219–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Mochizuki M, Saiki I, Yoo YC, Samukawa K, Azuma I. (1994) Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by a saponin of Panax ginseng, ginsenoside-Rb2. Biol Pharm Bull 17: 635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller H, Grausem B, Benveniste P, Chye ML, Tan CT, Song YH, Chua NH. (1995) Expression of the Hevea brasiliensis (H.B.K.) Mull. arg. 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-coenzyme A reductase 1 in tobacco results in sterol overproduction. Plant Physiol 109: 761–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutze MP, Peterson PA, Jackson MR. (1994) An N-terminal double-arginine motif maintains type II membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 13: 1696–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Pang Y, Wu W, Liao Z, Zhao L, Sun X, Tang K. (2006) Cloning and characterization of a root-specific expressing gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from Ginkgo biloba. Mol Biol Rep 33: 117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang H, Ding L. (2007) Investigation of ginsenosides in different parts and ages of Panax ginseng. Food Chem 102: 664–668 [Google Scholar]

- Shi YSC, Zheng B, Li Y, Wang Y. (2010) Simultaneous determination of nine ginsenosides in functional foods by high performance liquid chromatography with diode array detector detection. Food Chem 123: 1322–1327 [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S. (2001) Chemistry and cancer preventing activities of ginseng saponins and some related triterpenoid compounds. J Korean Med Sci (Suppl) 16: S28–S37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]