Despite evolutionary and structural differences between carboxysomes, Rubisco kinetics and in vivo performance are similar.

Abstract

The carbon dioxide (CO2)-concentrating mechanism of cyanobacteria is characterized by the occurrence of Rubisco-containing microcompartments called carboxysomes within cells. The encapsulation of Rubisco allows for high-CO2 concentrations at the site of fixation, providing an advantage in low-CO2 environments. Cyanobacteria with Form-IA Rubisco contain α-carboxysomes, and cyanobacteria with Form-IB Rubisco contain β-carboxysomes. The two carboxysome types have arisen through convergent evolution, and α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria occupy different ecological niches. Here, we present, to our knowledge, the first direct comparison of the carboxysome function from α-cyanobacteria (Cyanobium spp. PCC7001) and β-cyanobacteria (Synechococcus spp. PCC7942) with similar inorganic carbon (Ci; as CO2 and HCO3−) transporter systems. Despite evolutionary and structural differences between α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes, we found that the two strains are remarkably similar in many physiological parameters, particularly the response of photosynthesis to light and external Ci and their modulation of internal ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate, phosphoglycerate, and Ci pools when grown under comparable conditions. In addition, the different Rubisco forms present in each carboxysome had almost identical kinetic parameters. The conclusions indicate that the possession of different carboxysome types does not significantly influence the physiological function of these species and that similar carboxysome function may be possessed by each carboxysome type. Interestingly, both carboxysome types showed a response to cytosolic Ci, which is of higher affinity than predicted by current models, being saturated by 5 to 15 mm Ci. This finding has bearing on the viability of transplanting functional carboxysomes into the C3 chloroplast.

Cyanobacteria inhabit a diverse range of ecological habitats, including both freshwater and marine ecosystems. The flexibility to occupy these different habitats is thought to come in part from the carbon-concentrating mechanism (CCM) present in all species (Badger et al., 2006). The CCM comprises inorganic carbon (Ci; as carbon dioxide [CO2] and HCO3−) transporters for Ci uptake and protein microbodies called carboxysomes for CO2 concentration and fixation by Rubisco (Badger and Price, 2003). The CCM is believed to have evolved in response to changes in the absolute and relative levels of CO2 and oxygen (O2) in the atmosphere during the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis in cyanobacteria (Price et al., 2008).

There are two main phylogenetic groups within the cyanobacteria based on Rubisco and carboxysome phylogenies; α-cyanobacteria have α-carboxysomes with Form-IA Rubisco, whereas β-cyanobacteria have β-carboxysomes with Form-IB Rubisco (Tabita, 1999; Badger et al., 2002). Rubisco large subunit protein sequences from these two groups are closely related but nevertheless, distinguishable (Supplemental Fig. S1). In general, α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria occupy a quite different range of ecological habitats. The α-cyanobacteria are mostly marine organisms, with the majority of species living in the open ocean (Badger et al., 2006). Marine α-cyanobacteria live in very stable environments with high pH (pH 8.2) and dissolved carbon levels but low nutrients. They are characterized by small cells, very small genomes (1.6–2.8 Mb), and a few constitutively expressed carbon uptake transporters (Rae et al., 2011; Beck et al., 2012). They have been described as low flux, low energy cyanobacteria with a minimal CCM (Badger et al., 2006). Although these species are slow growing, oceanic cyanobacteria contribute as much as one-half of oceanic primary productivity (Liu et al., 1997, 1999; Field et al., 1998), suggesting that they may contribute up to 25% to net global productivity every year.

In comparison, β-cyanobacteria occupy a much more diverse range of habitats, including freshwater, estuarine, and hot springs and never reach the same levels of global abundance (Badger et al., 2006). They are characterized by larger cells, larger genomes (2.2–3.6 Mb), and an array of carbon uptake transporters, including those transporters induced under low Ci (Rae et al., 2011, 2013). In addition to these broadly defined α-groups and β-groups, there are small numbers of α-cyanobacteria that have been termed transitional strains (Price, 2011; Rae et al., 2011). These species (e.g. Cyanobium spp. PCC7001, Synechococcus spp. WH5701, and Cyanobium spp. PCC6307; Supplemental Fig. S1) live in marginal marine and freshwater environments and have a number of characteristics similar to β-cyanobacteria. For example, they have a more diverse range of Ci uptake systems and a significantly larger genome than closely related α-cyanobacteria, and it has been suggested that the additional genes encoding transport systems were acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) from β-cyanobacteria (Rae et al., 2011).

Although the carboxysomes from α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria are very similar in overall structure, in that they share an outer protein shell of common phylogenetic origin (Kerfeld et al., 2005), they are distinguished from each other largely by differences in the proteins, which seem to make up or interact with the interior of the carboxysome compartment (Supplemental Table S1). This finding suggests that their different structures today have arisen through periods of common and convergent evolution. Certain carboxysome shell proteins from α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes show regions of significant sequence homology. These proteins are denoted as CsoS1 to CsoS4 (in α-cyanobacteria) and CcmKLO (in β-cyanobacteria), and the homologous regions have been termed bacterial microcompartment domains (Kerfeld et al., 2010; Rae et al., 2013). Proteins with these domains are also found in bacterial microcompartments in proteobacteria. However, other identified carboxysome proteins do not show any sequence homology between α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes but may perform similar functional roles. For example, carbonic anhydrase activity is essential for carboxysome function, but its activity seems to be provided by a range of different proteins (β-CcaA, β-CcmM, and α-CsoSCA; Kupriyanova et al., 2013). Similarly, β-CcmM and α-CsoS2 could play similar roles in organizing the interface between the shell and Rubisco within the carboxysomes (Gonzales et al., 2005; Long et al., 2007).

The functioning of a carboxysome relies on a number of biochemical properties associated with the protein microbody structure. These properties include the biochemical/kinetic properties of Rubisco contained within carboxysomes, the conductance of the carboxysome shell to the influx of substrate ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) and the efflux of the carboxylation product phosphoglycerate (PGA), the conductance of the shell to the influx of bicarbonate and the efflux of CO2, and lastly, the manner in which bicarbonate is converted to CO2 within the carboxysomes. α-Carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes have the potential to differ in each of these properties. The flux of phosphorylated sugars across the shell has been postulated to be mediated by the pores in the hexameric shell proteins (Yeates et al., 2010; Kinney et al., 2011), which although similar, do differ between the two carboxysomes types. Bicarbonate and CO2 uptake processes are less well-defined but probably involve aspects of the way in which unique shell interface proteins interact with Rubisco, which also differs in that CsoS2 and CsoSCA are probably the interacting proteins involved in α-carboxysomes (Espie and Kimber, 2011), whereas CcmM and β-carboxysomal CA are variably involved in β-carboxysomes (Long et al., 2010). Finally, the Form-IA and Form-IB Rubisco proteins at the heart of carboxylation, although similar, have the potential to show different kinetic properties. Although Form-IB Rubiscos from β-cyanobacteria are well-characterized, the Form-IA counterparts have received very little attention. In addition, the CCM of very few strains of cyanobacteria have been studied at the level of biochemistry and physiology, and they have been almost exclusively β-cyanobacteria. As a result, there are significant gaps in our knowledge about the similarities and differences in functional traits between α-cyanobacterial and β-cyanobacterial strains. One important question that remains to be answered is whether α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes have intrinsic differences in their biochemical properties that influence the nature of the CCM, which is established within each broad cell type.

Because of the difficulties in isolating and assaying intact carboxysomes in vitro, the characterization of biochemical properties of carboxysomes is not easily addressed. One way forward is to study the properties of the CCM in detail in a model representative strain from each group and compare their characteristics to contrast the intracellular function of α-cell types and β-cell types. In the past, it has been restricted because of the difficulties in growing many of the open ocean α-cyanobacteria and their very different natures in relation to inorganic transporter composition. However, the availability of α-cyanobacteria transition strains, which grow well in the laboratory, has provided an opportunity to address this question. The α-cyanobacteria Cyanobium spp. PCC7001 (hereafter Cyanobium spp.), in particular, grows in standard freshwater media (BG11) and has growth and photosynthetic performance properties that closely match the model β-cyanobacteria, Synechococcus spp. PCC7942 (hereafter Synechococcus spp.); for this reason, Cyanobium spp. is ideal for a balanced comparison of the in vivo physiological properties of α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes in two species with relatively similar Ci-uptake properties.

Genome analysis of both strains indicates that Cyanobium spp. have many of the same carbon uptake systems present in Synechococcus spp. (Rae et al., 2011). In using two strains with such similar transport capacities, we aimed to shed light on aspects of the functional properties of carboxysomes in each strain and how these properties affect the operation of the CCM in α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria. Using both membrane inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) and silicon oil centrifugation, we investigated Ci pool sizes and CO2 uptake rates in both species for cells grown at high and low CO2. Comparative Rubisco properties and photosynthetic rates of each species were determined, and intracellular pools of RuBP and PGA were measured. In addition, we characterized a number of cellular properties to determine differences in the biochemical environments in which each carboxysome type exists. Together, the results provide a unique functional comparison of two distinct carboxysome types from phylogenetically disparate cyanobacteria.

RESULTS

The Photosynthetic Properties of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp.

In measuring the properties of carboxysome microcompartments in vivo, a number of approaches can be taken. Defining the relationships between photosynthetic CO2 fixation, cytosolic RuBP, PGA, the CO2 and HCO3− interconversion process, and the kinetic properties of purified Form-IA and Form-IB Rubisco enzymes allows a significant amount of information to be gained about the functioning of the intact carboxysomes. The experiments that follow were designed to collect these data for the α-cyanobacteria Cyanobium spp. and the β-cyanobacteria Synechococcus spp., and they are interpreted to understand the biochemical similarities and differences between the two carboxysomes types contained within each organism.

The Response of Photosynthesis, RuBP, and PGA Levels to Light and CO2

The Response of High-CO2-Grown Cells to Light

The response of photosynthesis was measured across a range of light intensities while maintaining a saturating level of external Ci (2 mm) for high-CO2-grown cells of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. The response to light was very similar for both cell types (Fig. 1A), showing similar maximum rates of photosynthesis on a chlorophyll (Chl) basis and a similar requirement for light in the light response curve.

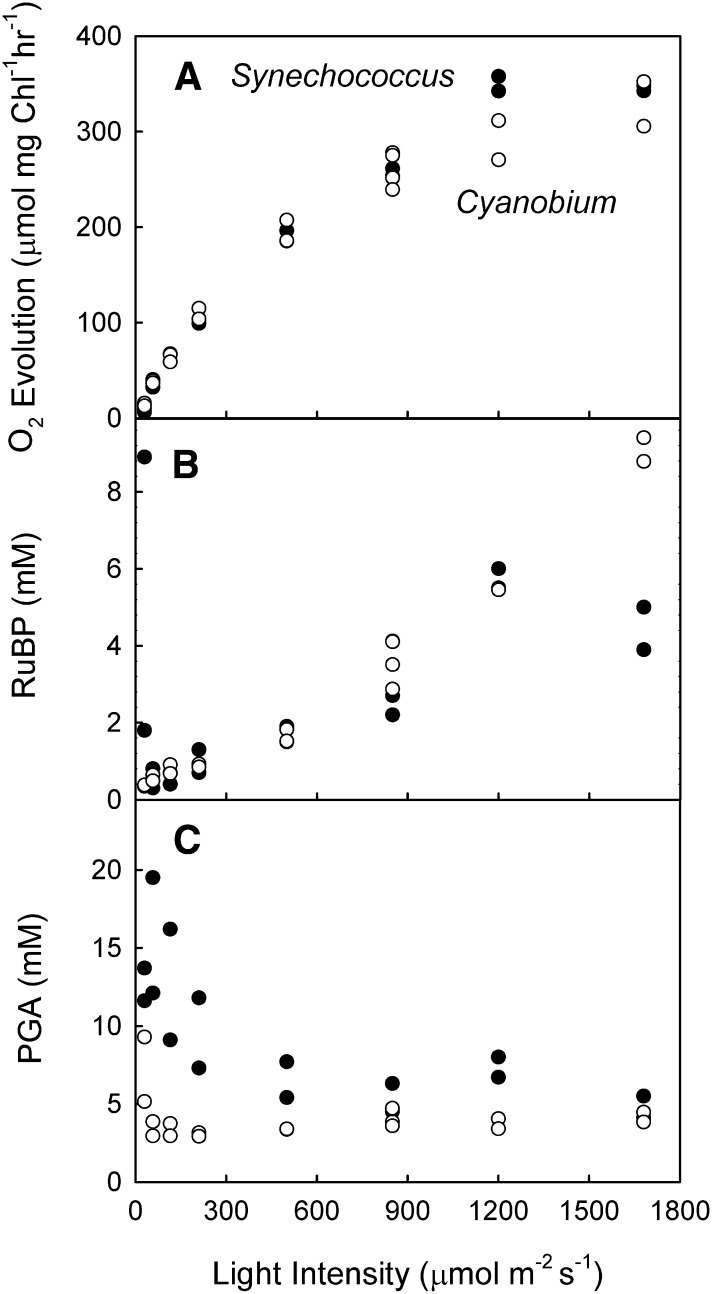

Figure 1.

The response of photosynthesis (A) and metabolite pools (B, RuBP; C, PGA) to light intensity in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells grown at high CO2. Cell density is 15 µg Chl mL−1. External carbon concentration is 2 mm. Data are from two separate experiments involving three biological replicates. Black symbols, Synechococcus spp.; white symbols, Cyanobium spp.

RuBP and PGA concentrations in the two strains showed broadly similar changes in response to increasing light intensity (Fig. 1, B and C). RuBP concentrations increased with increasing light intensity. The exception to this trend was the very high concentrations of RuBP found at the lowest light intensities (30 µmol photons m−2 s−1) in Synechococcus spp. In both species at higher light intensities, it is apparent that photosynthesis continues to be stimulated by cytosolic levels of RuBP in excess of 5 mm. As shown in Table I, it is 50 times the Rubisco active site concentration and 100 times the dissociation constant of RuBP (KRuBP) for Rubisco for both species if expressed on a cytosolic basis. PGA concentrations decreased with increasing light intensity, with Synechococcus spp. having higher concentrations than Cyanobium spp. The two strains show very similar changes in response to darkening, with a rapid decrease in RuBP and a corresponding rapid increase in PGA after the light was switched off (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Table I. Cellular and Rubisco properties of Cyanobium spp. and Synechococcus spp.

Measured cellular and Rubisco properties of Cyanobium spp. PCC7001 and Synechococcus spp. PCC7942 grown at both high and low CO2. Data are both measured experimentally and derived from experimental results. Values represent the means and sd of three replicates.

| Propertya |

Synechococcus spp. PCC7942 (β) |

Cyanobium spp. PCC7001 (α) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High CO2 | Low CO2 | High CO2 | Low CO2 | |

| Cellular properties | ||||

| Chl content (fg cell−1) | 14.1 ± 0.8 | 11.1 ± 0.1 | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 0.3 |

| Cell volume (µL mg Chl−1) | 58.6 ± 4.5 | 63.5 ± 6.1 | 57.0 ± 1.2 | 45.0 ± 2.6 |

| Cell volume (µL cell−1) | 8.3 × 10−10 | 7.0 × 10−10 | 4.8 × 10−10 | 2.5 × 10−10 |

| Rubisco active site density (nmol mg Chl−1)b | 6.9 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 1.6 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 1.6 |

| Rubisco catalytic propertiesc | ||||

| KCO2 | 169.2 ± 8.0 | 169.0 ± 6.9 | ||

| KRuBP | 69.9 ± 5.7 | 63.3 ± 4.9 | ||

| kcat (s−1) | 14.4 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | ||

| Derived properties | ||||

| Rubisco active site concentration (nmol cell−1) | 9.7 × 10−11 | 1.6 × 10−10 | 5.2 × 10−11 | 5.5 × 10−11 |

| Rubisco active site concentration (mm) | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

| Rubisco active sites per cell | 5.86 × 104 | 9.56 × 104 | 3.12 × 104 | 3.30 × 104 |

| Rubisco holoenzymes per cell | 7.32 × 103 | 1.19 × 104 | 3.90 × 103 | 4.13 × 103 |

| Rubisco Vmax (µmol mg Chl−1 h−1) | 358 | 741 | 198 | 318 |

| Rubisco Vmax (fmol cell−1 h−1) | 5.0 | 8.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

Cellular properties and Rubisco catalytic properties were determined experimentally as outlined in “Materials and Methods.” All other properties are derived from the measured values.

Rubisco active site densities were measured in crude cell extracts.

Rubisco kinetic parameters were measured from purified protein extracted from high-CO2-grown cells of each species.

The Response of Cells to External Ci

The response of both cell types to changes in external carbon was very similar in both low and high CO2 cells (Fig. 2, A and B). In both cell types, the affinity for external carbon increased markedly when cells were grown at low CO2 compared with high CO2 (Table II). This result indicates that both strains are able to induce a high Ci affinity state when grown at low CO2. The maximal photosynthetic rates do not change significantly between the two growth conditions in either strain. Cyanobium spp. had a significantly higher affinity for external Ci when grown at high CO2 compared with Synechococcus spp. (P < 0.01). Cyanobium spp. cells grown at low CO2 had a higher maximal photosynthetic rate than Synechococcus spp. (P < 0.01).

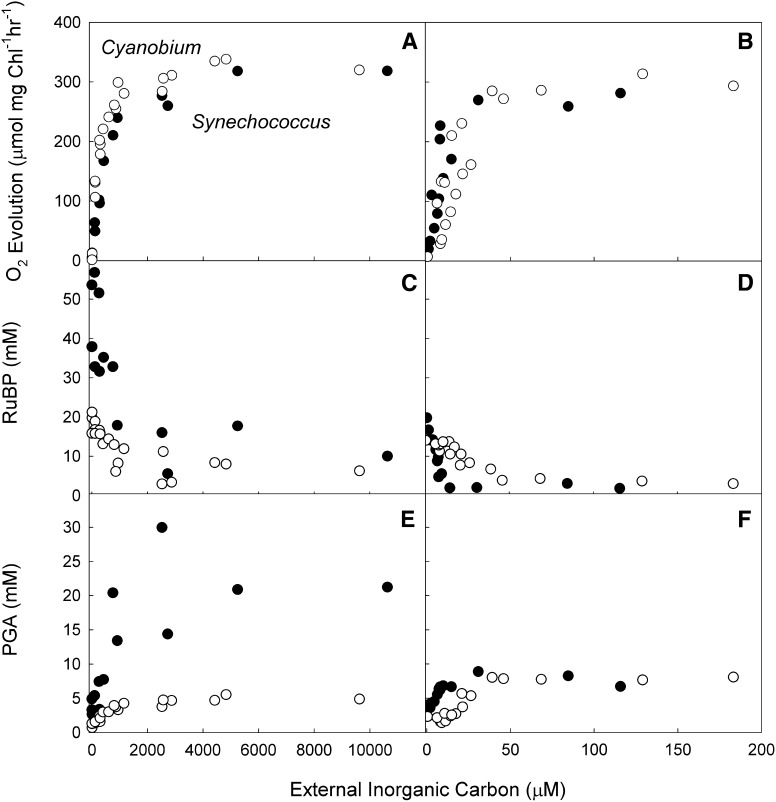

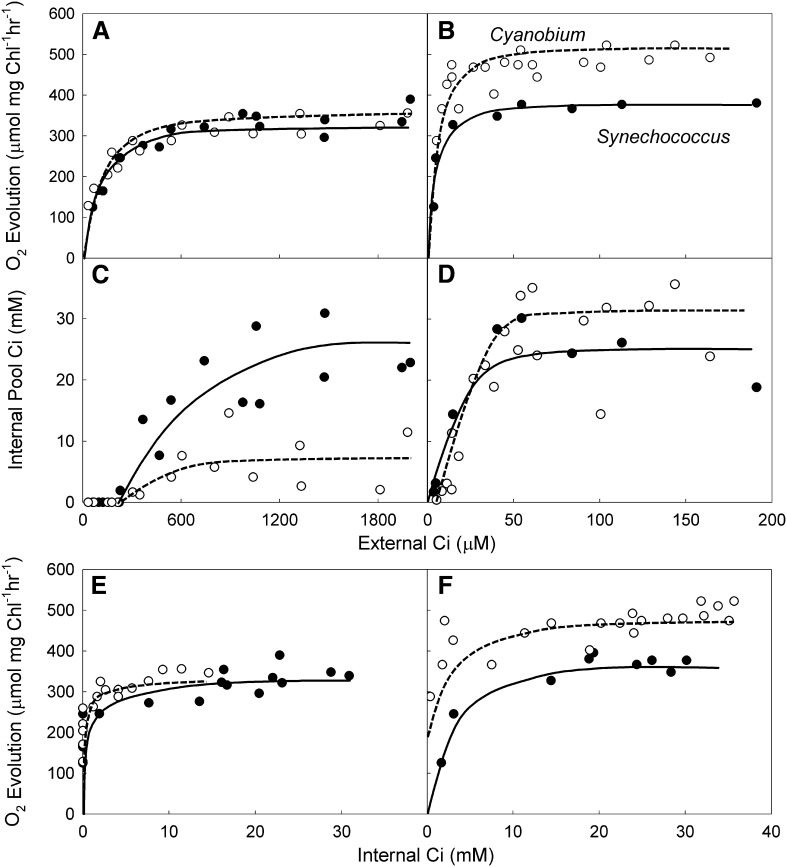

Figure 2.

The response of photosynthesis and metabolite pools in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. to carbon concentration in the medium. Cells grown at high (A, C, and E) or low (B, D, and F) CO2. Cell density is 15 µg Chl mL−1, and irradiance was 1,200 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Data are from three to six separate experiments. Black symbols, Synechococcus spp.; white symbols, Cyanobium spp.

Table II. Photosynthetic carbon response parameters of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp.

Maximum photosynthetic rates (Vmax) and CO2 concentrations required to reach half-maximum photosynthetic rates (K0.5) for the cyanobacteria Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. Values are means ± sd of four replicates.

The overall pattern of change of RuBP and PGA concentrations in response to increasing external Ci was similar in the two strains and between cells grown at high and low CO2 (Fig. 2, C–F). Increasing external Ci concentration resulted in decreasing internal RuBP concentrations, whereas internal PGA concentrations showed the inverse response. In high-CO2-grown cells, Synechococcus spp. had larger internal pools of both RuBP and PGA compared with Cyanobium spp. Cells of the two strains grown at low CO2 had similar internal concentrations of RuBP and PGA, but the response of these pools to increasing external Ci was different. In low-CO2-grown Synechococcus spp., internal concentrations of both PGA and RuBP changed rapidly in response to a small increase in external Ci, reflecting the altered response of photosynthesis to external Ci. PGA concentrations increased to a maximum of 8 mm and RuBP levels fell to a minimum of 2 mm at about 20 µm external Ci. In contrast, the concentrations of these metabolites responded more gradually to changes in external Ci in Cyanobium spp.

At saturating CO2, there were significant differences in the minimum RuBP pool sizes of both species from cells grown at both high and low CO2 (Fig. 2). In general, this CO2 saturated point represents a condition where RuBP concentrations become limiting for photosynthesis, because it is where light is now the limiting input. For high-CO2 cells of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp., it is 15 and 8 mm RuBP, respectively. However, for low-CO2 cells, the equivalent minimum is reached at around 1 and 2 mm RuBP, respectively.

Properties of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. Cell Structure

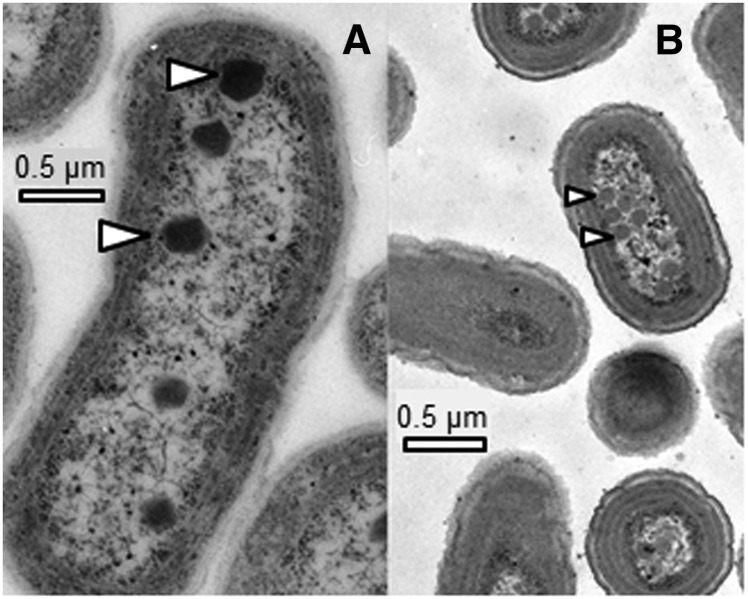

Transmission electron microscopy images show that Synechococcus spp. cells were larger than Cyanobium spp. cells (Fig. 3). Chl and volume measurements in Table II confirm this observation. There were also differences in the number and size of carboxysomes in the two strains. Synechococcus spp. have a few large carboxysomes, whereas Cyanobium spp. have many small carboxysomes. A summary of derived carboxysome properties for high- and low-CO2-grown cells of each species is shown in Table III.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of Synechococcus spp. (A) and Cyanobium spp. (B). Cells were grown at low CO2. Examples of carboxysomes are indicated by white arrows.

Table III. Properties of carboxysomes from Cyanobium spp. and Synechococcus spp. cells grown at high and low CO2.

Derived properties of Cyanobium spp. and Synechococcus spp. carboxysomes based on experimentally determined carboxysome dimensions and cellular Rubisco quantities.

| Property |

Synechococcus spp. (β) |

Cyanobium spp. (α) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High CO2 | Low CO2 | High CO2 | Low CO2 | |

| Carboxysome diameter (nm)a | 240 ± 54 (162) | 234 ± 37 (50) | 103 ± 8.9 (85) | 104 ± 9.9 (170) |

| Total carboxysome volume (nm3)b | 4.38 × 106 | 4.06 × 106 | 3.46 × 105 | 3.57 × 105 |

| Internal carboxysome volume (nm3)c | 3.81 × 106 | 3.51 × 106 | 2.72 × 105 | 2.80 × 105 |

| Carboxysome surface area (nm2)b | 1.38 × 105 | 1.31 × 105 | 2.54 × 104 | 2.59 × 104 |

| Surface area-volume ratio | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.073 | 0.073 |

| Rubisco active sites per carboxysomed | 2.49 × 104 | 2.30 × 104 | 1.78 × 103 | 1.83 × 103 |

| Rubisco holoenzymes per carboxysomed | 4,042 | 3,732 | 288 | 297 |

| Carboxysomes per celle | 2.4 | 4.2 | 17.6 | 18.1 |

Carboxysome diameters were determined experimentally from electron microscopic analysis and represent the maximum cross-sectional width. Numbers are mean values ± sd, with the number of measured carboxysomes in parentheses.

Volume and surface area of carboxysomes calculated for idealized icosahedrons of the diameters listed.

Internal volumes are calculated for ideal icosahedrons assuming shell thicknesses of 4 nm for α-carboxysomes (Iancu et al., 2007) and 5.5 nm for β-carboxysomes (Kaneko et al., 2006).

Rubisco quantities per carboxysome are estimated assuming that Rubisco holoenzymes occupy spheres of diameter of 12 nm and have packing densities of 74% (Kepler packing). This arrangement is a realistic packing arrangement for both α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes based on estimated stoichiometries for both carboxysome types (Long et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2012). The resulting packing arrangement results in a Rubisco active site concentration of 10.9 mm within carboxysomes of both types. Reducing the volume occupied by Rubisco to 11-nm-diameter spheres increases the active site concentration within carboxysomes to 14.1 mm and reduces the estimated number of carboxysomes per cell by approximately 1.3-fold. This range of Rubisco volumes is estimated from the crystal structure of Synechococcus spp. PCC 6301 Rubisco (Newman and Gutteridge, 1990), which is identical to that of Synechococcus spp. PCC 7942.

Carboxysomes per cell were calculated from modeled carboxysome volumes, assumed Rubisco packing densities (above), and Rubisco active site concentration data in Table II.

The Kinetic Parameters of α-Rubisco and β-Rubisco

The Rubisco content of both species was measured in crude cell extracts from the stoichiometric binding of Rubsico’s tight-binding inhibitor 14CABP. The two strains had a very similar concentration of Rubisco (calculated from volume and active site density measurements; Table II). In both strains, Rubisco content was higher (2-fold) in low-CO2-grown cells. Rubisco reaction kinetics were measured for purified Rubisco protein from both species, and it was found that α-Rubisco and β-Rubisco (Form-IA and Form-IB, respectively) had remarkably similar properties, with both showing a dissociation constant of CO2 (KCO2) value of around 169 µm. The kcat value was around 14 s−1 for Synechococcus spp. and somewhat lower for Cyanobium spp. (9 s−1). KRuBP values were also similar at around 65 µm. The kinetic properties of the two Rubiscos were so similar that we were compelled to check the origin of the Cyanobium spp. Rubisco, which was confirmed by proteomic analysis (data not shown).

Ci Uptake and Exchange in Cyanobium spp. and Synechococcus spp.

CO2 Uptake Processes

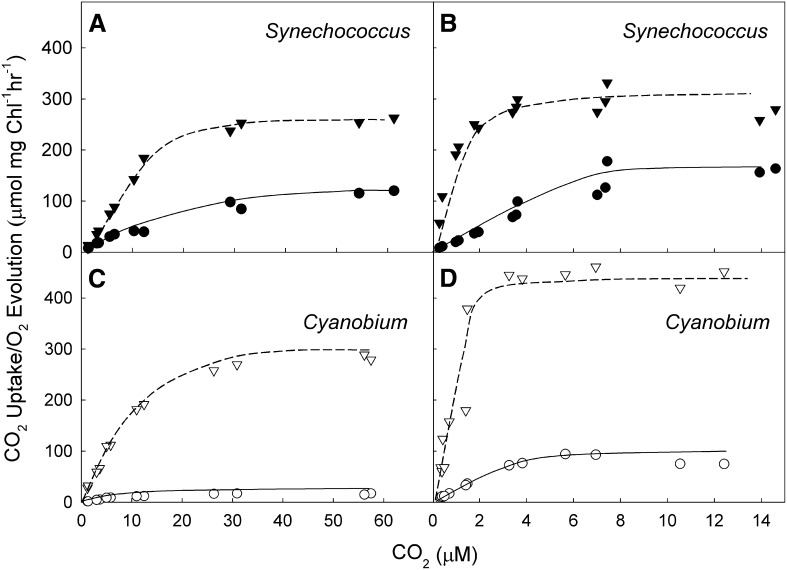

The maximum rate of CO2 uptake occurs 5 to 10 s after illumination (Fig. 4), whereas the maximum net O2 evolution rates were achieved after 30 to 90 s for both species. The kinetic parameters estimated for the CO2 uptake systems in both strains are shown in Table IV. The cells of both strains showed an increase in affinity for CO2 when grown at low CO2 (Fig. 4). Initial CO2 uptake rates were higher in Synechococcus spp. compared with Cyanobium spp. in both high- and low-CO2-grown cells. However, affinity for CO2 was greater in Cyanobium spp. (Table IV). Cyanobium spp. also showed a greater increase in CO2 uptake capacity (>4-fold) under low-CO2 conditions compared with Synechococcus spp. (<2-fold). Overall, the data indicate that Synechococcus spp. has a stronger CO2 uptake system, which contributes to Ci accumulation, and that HCO3− uptake plays a greater role in Cyanobium spp.

Figure 4.

Response of initial CO2 uptake and photosynthesis to external CO2 in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. Cells were grown at high (A and C) or low (B and D) CO2. Cell density is 15 µg Chl mL−1 for high-CO2-grown cells and 3 µg Chl mL−1 for low-CO2-grown cells. Irradiance was 1,200 µmol photons m−2 s−1. No external carbonic anhydrase was added in these experiments. Data are from three experiments. Lines are hand drawn to indicate the inferred response. Black symbols, Synechococcus spp.; circles, initial CO2 uptake; triangles, maximum O2 evolution rate; white symbols, Cyanobium spp.

Table IV. Initial CO2 uptake parameters of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp.

Maximum initial CO2 uptake rates (Vmax) and CO2 concentrations required to reach half-maximum initial CO2 uptake rate (K0.5) for the cyanobacteria Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. Values are means ± sd. Numbers in parentheses denote replicates.

Internal CO2/HCO3− Exchange Processes

When HCO3− enters the cyanobacterial cell, it can be interconverted with CO2 through the combined action of carboxysomal CA and the cytosolic NDH1-CO2 uptake complexes (Price et al., 2008). This process can be monitored conveniently by the use of 18O-labeled Ci (H13C18O3) after the loss of 18O into the unlabeled water medium (Maeda et al., 2002). In general, the patterns of 18O exchange out of labeled CO2 into water are similar for Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells in both the light and the dark (Supplemental Fig. S3).

The Internal Ci Pool in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. Cells and Its Relationship to Photosynthesis

The internal Ci pools of cyanobacterial cells can be measured using either MIMS or silicone oil centrifugation, and both approaches were used here. The MIMS kinetics of Ci uptake by Synechococcus spp. at high external Ci concentrations were similar to those kinetics found previously (Badger et al., 1985; Supplemental Fig. S4). There was rapid initial Ci uptake followed by a second slower uptake phase. However, Ci uptake into cells did not routinely show this biphasic pattern in Synechococcus spp. for lower external Ci concentrations (Supplemental Fig. S4). In contrast, Cyanobium spp. cells often showed very different initial uptake kinetics in that they lacked a rapid uptake phase (Supplemental Fig. S5) and indeed, showed an initial slow phase in Ci uptake. However, efflux kinetics (after light-off phase) showed a consistent pattern, and this phase was better suited to measurement of internal Ci pool sizes. We, therefore, estimated internal Ci pools and their relationship to steady-state photosynthesis from measurements made with MIMS from the light-off phase.

Figure 5, C and D shows the effects of external Ci concentration on internal Ci pool sizes in the two strains grown at high and low CO2. In low-CO2-grown cells, the effect of external Ci on pool size was similar in the two strains (Fig. 5D). For high-CO2-grown cells, Synechococcus spp. showed an ability to accumulate higher concentrations of internal Ci at high external Ci (Fig. 5C). Photosynthesis, measured as O2 evolution, measured immediately before cell darkening was also recorded, and it enabled a plot of internal Ci, rather than external Ci, against photosynthesis. These plots (Fig. 5, E and F) show that, in both species, an overaccumulation of internal Ci is apparent at the higher concentrations of external Ci, with photosynthesis being saturated at much lower concentrations of internal Ci than were achieved at the highest levels of external Ci. Indeed, photosynthesis seemed to be saturated by internal concentrations of Ci much lower than the pools commonly observed under conditions where saturating Ci concentrations are used for measurement.

Figure 5.

Internal Ci pools in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells measured using mass spectrometry. The effect of external Ci on photosynthesis and internal Ci pools on high-CO2-grown (A and C) and low-CO2-grown (B and D) cells. Rates of photosynthesis at calculated internal Ci pools in high-CO2-grown (E) and low-CO2-grown (F) cells are shown. Measurements were made on a mass spectrometer from cyanobacterial cell suspensions with Chl density of 15 µg Chl mL−1 for high-CO2 experiments and 3 µg Chl mL−1 for low-CO2 experiments. Irradiance was 1,200 µmol photons m−2 s−1; 30 µg mL−1 CA was present in all experiments. In each instance, data presented are from three separate experiments. Lines are hand drawn to indicate the inferred response. Black symbols, Synechococcus spp.; white symbols, Cyanobium spp.

In comparing the two species, high-CO2-grown cells Synechococcus spp. had larger Ci pool sizes than Cyanobium spp. at all external Ci concentrations above 250 µm (Fig. 5C), but these differences occurred at external Ci concentrations that are in excess of those concentrations required to saturate photosynthesis. For low-CO2-grown cells, the pool size at which maximum photosynthetic rates were recorded in low-CO2-grown Cyanobium spp. (4 mm) was much lower than that in Synechococcus spp. (15 mm; Fig. 5F), although the pool sizes at saturating Ci were similar in the two species (Fig. 5D).

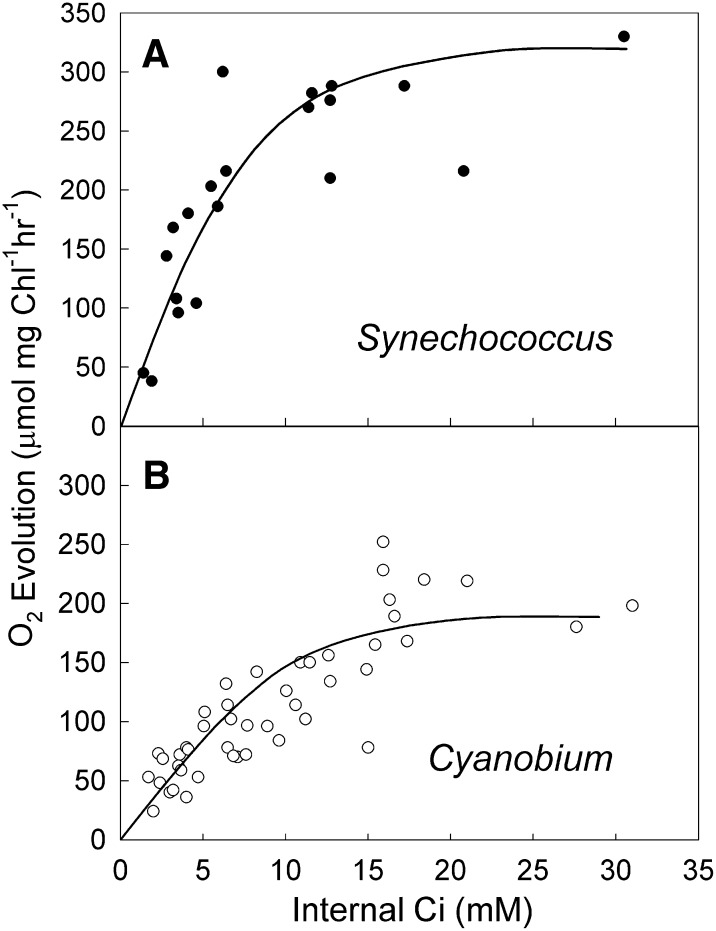

Internal Ci pool sizes measured using MIMS analysis (Fig. 5) clearly differ from those pool sizes measured using silicon oil centrifugation (Fig. 6) in that internal Ci pools are apparent, even at the lowest external Ci, using the latter technique. For Synechococcus spp. cells, it seems that photosynthesis is saturated by an internal pool size of around 15 mm, whereas for Cyanobium spp., it is 15 to 20 mm. The results are consistent with the notion that RuBP refixation of internal Ci in the dark may be underestimating Ci pools at limiting external Ci using the MIMS technique.

Figure 6.

Internal Ci pools in high-CO2-grown Synechococcus spp. (A) and Cyanobium spp. (B) cells measured using the silicon oil filtration method. Measurements were made using cyanobacterial cell suspensions at a density of 4 µg Chl mL−1. Irradiance was 400 µmol photons m−2 s−1. In each instance, data presented are from six separate experiments. Lines are hand drawn to indicate the inferred response. Black symbols, Synechococcus spp.; white symbols, Cyanobium spp.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here are, to our knowledge, the first direct comparisons of α-cyanobacteria (Cyanobium spp.) and β-cyanobacteria (Synechococcus spp.) with similar complements of Ci transporter systems, thus allowing us to ask questions about the differences in physiology and function that might be associated with their respective carboxysome types. In fact, it is the similarity of Ci uptake processes in our two chosen species that make it possible to do a fair comparison of the two carboxysomes types in vivo. For instance, comparison of carboxysome performance in a higher light-adapted strain with a potent CCM would not be entirely valid against a strain that is low light adapted with a weak CCM. Thus, some effort has been spent here to establish the precise comparative details of Ci uptake, Ci internal pool size with photosynthesis, and RuBP/PGA metabolite pools before considering the comparative properties of carboxysomes function. The broad conclusions that can be drawn indicate that the possession of different carboxysome types does not significantly influence the physiological function of the cell and that similar carboxysome function may be possessed by each carboxysome type, highlighting the question of whether there are physiological advantages of α-carboxysome or β-carboxysome types that influence ecological competitiveness. This general finding was not expected given the evolutionary origin of the smaller α-carboxysomes from α-cyanobacteria found in oceanic niches that feature low growth rates and exposure to low light and nutrient levels.

Induction of Enhanced CCM Physiology at Low CO2

Both strains showed evidence of CCM induction when grown under low CO2, and in general, the photosynthetic characteristics of the two strains in response to light and external Ci concentration were very similar (Figs. 1 and 2; Tables II and IV). Many β-cyanobacteria have shown similar evidence of CCM induction (e.g. Anabaena variablis [Kaplan et al., 1980], Synechococcus spp. PCC6301 [Badger and Gallagher, 1987; Mayo et al., 1989], and Synechococcus spp. PCC7002 [Klughammer et al., 1999]). There is also evidence that a subset of α-cyanobacteria induces a CCM when grown at low CO2 (e.g. Synechococcus spp. WH7803; Hassidim et al., 1997). In contrast, other α-cyanobacteria, including transition strains, do not appear to show induction of CCM physiology, such as Synechococcus spp. WH7803 (Karagouni et al., 1990). Recently, Rae et al. (2011) and B.D. Rae, B. Förster, M.R. Badger, and G.D. Price (unpublished data) found that the transition strains Synechococcus spp. WH5701 and PCC6307 showed high affinity photosynthetic characteristics regardless of CO2 concentration during growth (K0.5 Ci = 20–30 µm).

In this study, we showed that Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. grown at low CO2 both increased the affinity and capacity for CO2 uptake (Table IV). Synechococcus spp. has two types of CO2-uptake systems; a low-affinity system (NDH-14), which is constitutively expressed, and a high-affinity system (NDH-13), which is induced under low-CO2 conditions (Price et al., 2008). Analysis of the Cyanobium spp. genome shows that it also has both systems. The kinetic measurements recorded in this study suggest that the expression of these transporter genes is under similar control as the expression in Synechococcus spp.

RuBP and PGA Responses to Light and Ci

Response to Light

RuBP and PGA concentrations in response to light and Ci were measured in an effort to gain insight into the metabolic response of the carboxysome in relation to Rubisco substrate and product. The response to light intensity at saturating Ci (Fig. 1) showed that increasing light increased the concentrations of RuBP, which has been found in plants and the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (von Caemmerer et al., 1983; Badger et al., 1984) because of increased RuBP synthesis rate at high light. PGA concentrations, however, showed a decrease with increasing light in both species (Fig. 1). This finding is the opposite of what has been seen in plants and Chlamydomonas spp., where increasing carboxylation and PGA production driven by increasing RuBP lead to increases in PGA steady-state levels. The reasons for this difference are not clear, but presumably, they are because light stimulation of PGA consumption reacts more significantly than Rubisco carboxylation. The recently discovered light activation of PGA kinase by thioredoxin in Synechocystis spp. PCC6803 may be responsible for this stimulation (Tsukamoto et al., 2013). The decline in PGA at very low light intensities in Synechococcus spp. is consistent with the observed increase in RuBP under these same conditions.

Response to Ci

The response to Ci at saturating light (Fig. 2) was also similar in both Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. At limiting Ci, RuBP accumulated and was reduced to its lowest levels when Ci was saturating for photosynthesis. This response is a typical response seen in plants and Chlamydomonas spp. PGA shows the inverse of this response, with low concentrations at limiting Ci and the highest concentrations at saturating Ci. The maximum concentrations of PGA and RuBP accumulated at low Ci in Synechococcus spp. are about 2-fold higher than for Cyanobium spp.

RuBP concentrations at high Ci declined to their lowest levels and reflect the point where either a limiting rate of RuBP synthesis by the light reactions or the Vmax for Rubisco is reached. In plants, the Vmax for Rubisco significantly exceeds the light-saturated capacity of the light reactions (Farquhar et al., 1980; von Caemmerer and Edmondson, 1986), and the limitation at high CO2 is imposed by the capacity of the light reactions to provide ATP and NADPH. In cyanobacteria, the measured Vmax for Rubisco does not significantly exceed the light and Ci saturated rate of photosynthesis (Figs. 1 and 2; Table I), and there must be questions about what limits photosynthesis at high light and high Ci. RuBP concentrations at high Ci decline to different levels in high- and low-CO2-grown cells of both species. In high-CO2 cells, concentrations of 5 to 10 mm were reached at high Ci, whereas in low-CO2 cells, it was reduced to 0.3 to 0.5 mm. The reasons for these differences are not entirely clear. However, the facts that Rubisco content is up to 2-fold higher in low-CO2 cells and Chl per cell is reduced (Table I) are consistent with the possibility that the Ci saturated rate of photosynthesis is limited by Rubisco capacity in high-CO2 cells and electron transport capacity in low-CO2 cells.

Evidence for Similar Function of α- and β-Carboxysomes

Rubisco Content

The two strains examined in this study had Rubisco active site densities, which were measured on a Chl basis (6 to 14 nmol mg Chl−1; Table I), similar to those densities measured previously in Synechococcus spp. at high and low CO2 (Emlyn-Jones et al., 2006; Tables I, III, and IV). Nonetheless, Rubisco active site density increased in both strains in response to low CO2 (Table I), doubling in Synechococcus spp. and increasing approximately 1.5-fold in Cyanobium spp. However, Rubisco active site concentration (expressed on a cellular basis; mol cell−1) increased approximately 1.5-fold in Synechococcus spp. but remained relatively constant in Cyanobium spp. in response to low CO2. These apparent differences were because of changes in Chl content per cell and cell volume in response to growth under low CO2 (Table I). These changes in cell volume in response to CO2 resulted in similar Rubisco active site concentrations expressed on a cell volume basis (millimolar) in both strains, and an approximate doubling of these values under low-CO2 growth (Table I). Although Rubisco active site content in β-cyanobacteria has been found to decrease at low CO2 (Mayo et al., 1989) or remain largely unchanged (Karagouni et al., 1990; Long et al., 2011), the results presented here show that cellular volumetric Rubisco active site concentrations (millimolar) are very similar between the two strains and that both respond the same under low CO2.

Carboxysome and Rubisco Properties

Consistent with previous studies of α-carboxysome- and β-carboxysome-containing cyanobacteria and proteobacteria (Rae et al., 2013), α-carboxysomes are smaller and more numerous per cell, and the Rubisco content per cell was similar in cells grown at both high and low CO2. However, the concentration of Rubisco per unit volume was similar in both carboxysome types (assuming similar packing densities). Rubisco packing densities of 74% (Kepler packing) of the internal carboxysome volume are realistic packing arrangements for both α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes based on estimated stoichiometries for both carboxysome types (Long et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2012). Based on this arrangement, the concentration of Rubisco active sites within carboxysomes (10.9 mm for both carboxysome types; Table III) is considerably higher than that found in the stroma of C3 plants, where concentrations of 1 to 2 mm are most common (Badger et al., 1984; von Caemmerer and Edmondson 1986).

The kinetics of the purified Rubisco protein from Synechococcus spp. PCC6301 (identical to Rubisco from Synechococcus spp. PCC7942) and Cyanobium spp. were very similar (Table I). Given the evolutionary adaptation of Rubisco to match the level of CO2 concentration found in its operational environment (Badger et al., 1998), the almost identical KCO2 values (169 µm) would suggest that both the cyanobacterial α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes seem to produce a similar concentration of CO2 within the carboxysome. The similar Rubisco kinetics are perhaps surprising given that the proteins have significant amino acid sequence differences. Because of the similarities in kinetics, we were compelled to confirm the identity of purified Cyanobium spp. Rubisco by proteomic analysis (data not shown). A BLAST comparison of Rubisco from the two strains shows a 75% identity (85% similarity) of large subunits and 39% identity (55% similarity) of small subunits. Parameters for Synechococcus spp. fall within the range reported for other β-cyanobacteria (KCO2, 150–300 µm; kcat, 2.6–11 s−1; KRuBP, 56 µm; Greene et al., 2007; Whitney and Sharwood, 2007; Badger and Bek, 2008). There are very few data on Rubisco from α-cyanobacteria. Jordan and Ogren (1981) found a KCO2 of 121 µm in Rubisco from Coccochloris peniocystis (Cyanobium spp. PCC6307), and Synechococcus spp. WH7802 is reported to have a Rubisco KCO2 similar to Synechococcus spp. PCC7942 (Hassidim et al., 1997). Data for other noncyanobacterial Form-IA Rubiscos suggest that the protein from these proteobacteria has a higher affinity for CO2 compared with Rubisco from β-cyanobacteria (KCO2 = 30–140 µm; Tabita, 1999), which may be because these organisms do not have carboxysomes and therefore, cannot concentrate CO2 at the site of fixation to the same extent (Badger and Bek, 2008). The KCO2 for the α-carboxysome–containing proteobacterium Halothiobacillus neapolitanus Rubisco was estimated at approximately 165 µm (Dou et al., 2008). However, one reported value for an α-cyanobacterium, Prochlorococcus marinus MIT9313, of KCO2 = 750 µm (Scott et al., 2007) is hard to reconcile, because it would imply that internal Ci > 100 mm would be needed to achieve saturation of CO2 fixation; this result would seem unlikely for a low-light-adapted organism that has genes for only two putative HCO3− transports (Rae et al., 2011). Given the similarity of Rubisco gene products from Cyanobium spp. and MIT9313 (Supplemental Fig. S1; their CbbL sequences are 95.1% identical), a KCO2 value closer to 169 µm would have been expected for MIT9313.

Internal Ci Interconversion

A key function of the cyanobacterial CCM is the ability to convert accumulated HCO3− to CO2 within the carboxysome. It is largely catalyzed by carboxysomal CA activity associated with the inner surface of the carboxysome shell (So et al., 2004; Sawaya et al., 2006; Long et al., 2007; Cot et al., 2008). This activity, coupled with the recovery and recycling of leaked CO2 by the thylakoid NDH13/4 CO2 uptake complexes (Badger et al., 2002; Price et al., 2008), give rise to the apparent light stimulation of Ci/oxygen isotope exchange in the external medium (Supplemental Fig. S3). This phenomenon has been well-established for β-cyanobacteria, but its occurrence in α-cyanobacteria has not been studied. The results in Supplemental Figure S3 show that Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells grown at high and low CO2 show very similar patterns of light-stimulated 18O exchange of external Ci species. This finding is consistent with the conclusions that Ci species interconversion within α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes is occurring in a similar manner and that it is dependent on the light-stimulated supply of Ci species to the cytosol by the HCO3− transporters, the conversion of CO2 to HCO3− by the NDH13/4 CO2 uptake complexes in the cytosol, and the interconversion of HCO3− and CO2 within the carboxysome (Badger et al., 2002; Price et al., 2008). Low-CO2-grown Cyanobium spp. cells are a slight exception, showing internal exchange activity that occurs in the dark (Supplemental Fig. S3), which may be because of the possibility that Ci transport systems are not fully inactivated in the dark.

Response of Carboxysomes to Cytosolic Ci

A key piece of carboxysome physiology that is largely unknown because of our inability to isolate and assay fully functional cyanobacterial carboxysomes (particularly β-carboxysomes) is the response of carboxysome Rubisco activity to external [HCO3−]. Models of carboxysome function have not been extensively developed, but our current understanding assumes that HCO3− and CO2 have permeabilities that allow sufficient influx of HCO3− but restrict efflux of CO2. Models also assume that, at the supposed pH of the carboxysome, HCO3− and CO2 are in rapid equilibrium, and therefore, the CO2 level can be calculated from the pH and the carboxysomal [HCO3−] (Badger and Price, 1989). As a result, if the carboxysome pH is assumed as 8, then carboxysomal Rubisco will respond to external HCO3− in a similar manner to isolated Rubisco assayed at pH 8 (Badger et al., 1985). Consequently, the K0.5Ci for carboxysomal CO2 fixation will be about 10 mm, and it will take up to 100 mm Ci to saturate Rubisco, which can be seen in Supplemental Figure S6 for a modeled α-carboxysome. This response is similar to those responses measured for apparently intact α-carboxysomes from chemolithotrophic proteobacteria (Dou et al., 2008).

The results shown in Figures 5 and 6 raise the possibility that in vivo α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes may respond to significantly lower concentrations of internal cytosolic HCO3− than previous models would predict (Badger and Price, 1989). Data from MIMS measurements (Fig. 5) indicate potential saturation of carboxysome CO2 fixation by as little as 5 mm internal Ci in high- and low-CO2-grown cells of both cell types. Silicon oil centrifugation experiments (Fig. 6) attempt to correct for internal refixation of Ci by high-RuBP pools at low external Ci and produced results that indicate saturation by around 15 mm internal Ci. Using MIMS, Price and Badger (1989a) found that, when human CA was expressed in the cytosol of both high- and low-CO2-grown Synechococcus spp., internal Ci of 6 mm was sufficient to saturate photosynthesis. Experiments by Karagouni et al. (1990) indicate that a number of marine α-Synechococcus species appeared to accumulate very low internal Ci pools during photosynthesis. However, Salon and Canvin (1997), also using MIMS, found a much higher requirement for internal Ci in βSynechococcus spp. UTEX625, which is more consistent with the response modeled in Supplemental Figure S6 for the conventional model (hydration-dehydration ratio [h/d] = 50).

If carboxysomes are saturated by much lower cytosolic Ci concentrations (around 15 mm) in α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria, which is indicated in this study, then a mechanism for it in carboxysome function must exist. Two possible reasons can be proposed, both of which can be postulated to affect the ratio of the hydration-dehydration rate constants for the interconversion of HCO3− and CO2 species within the carboxysome. At the most simple level, the pH in the carboxysome could be significantly less than is assumed, thus allowing the production of higher levels of CO2 for a given [HCO3−]. Rubisco produces one net proton per reaction using imported HCO3− to supply CO2 for Rubisco carboxylation, which could acidify the interior of the carboxysome. Menon et al. (2010) measured the proton equilibration in α-carboxysomes from H. neapolitanus and concluded that internal pH was the same as external pH, but this measurement was done in the absence of a Rubisco reaction (no RuBP present) and does not preclude a more acidic carboxysome interior when Rubisco is active.

A second mechanism may be that both α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes use a peripheral carbonic anhydrase to convert HCO3− to CO2 (Rae et al., 2013), and it may function quite differently from the currently assumed action of bringing all Ci species in the carboxysome to chemical equilibrium. The peripheral CA is supplied with HCO3− from the cytosol and converts it to CO2. If some function of this arrangement favors this reaction over the back reaction of hydration of CO2 to HCO3−, then the steady-state equilibrium will be shifted in favor of CO2. Supplemental Figure S6 also shows the modeled response of a carboxysome when the h/d (h/d = 5) is reduced 10-fold by either reduced pH or specialized CA function. It is clear that reduction in the h/d has the potential to increase the affinity of carboxysomal Rubisco to external HCO3− and produce the results observed in this study. This possibility needs to be explored further, because it has significant ramifications for understanding the function of carboxysomes and the operation of the CCM in α-cyanobacteria and β-cyanobacteria. Another important implication relates to future plans to improve photosynthesis by placing functional carboxysomes in the chloroplast of C3 crop plants (Price et al., 2013); here, a Ci accumulation target of up to 15 mm Ci would be indicated rather than previous estimates.

Are There Differences in α- and β-Cyanobacteria and Their Carboxysomes?

The studies here indicate a remarkable similarity of the photosynthetic and CCM properties of β-Synechococcus spp. and α-Cyanobium spp. used for this study. Clearly, HGT events have played a key role in the adaptation of Cyanobium spp. cells to freshwater habits (Rae et al., 2011), because both of our model species show induction of the CCM activity at low CO2 and achieve similar affinities for external Ci. Their similar suites of Ci transporter complexes (Supplemental Table S1) function to establish similar internal Ci pools, which drive the function of Rubisco in their carboxysomes. One specific exception is the lower capacity for active CO2 uptake in Cyanobium spp. cells. Attempts to uncover dissimilarities in the function of their carboxysomes do not indicate specific differences. As already discussed, α-carboxysomes are smaller and more numerous, and when combined with similar active site densities of Rubisco in both carboxysomes types, they result in similar cellular capacities for volumetric Rubisco active site concentration (Tables I and III).

Measured responses of RuBP against external Ci were found to be similar between species and for cells grown at high or low CO2 (Fig. 2). High Ci cells of Synechococcus spp., however, tended to have higher levels of RuBP than Cyanobium spp. at very low external Ci (Fig. 2C). The permeability of carboxysomes to RuBP has not been well-defined, but results of the work by Dou et al. (2008) suggest the KRuBP for intact α-carboxysomes from H. neapolitanus is around 146 to 175 µm, some 2-fold higher than the KRuBP of the purified Form-IA Rubisco enzyme measured in this study (Table I). This finding would suggest some permeability barrier and would be consistent with the measured RuBP levels of low-CO2-grown cells assayed under high Ci conditions where RuBP was not drawn down below 300 to 500 µm in both cell types (Fig. 2D). Similar responses to cytosolic Ci were also measured in both cell types (Figs. 5 and 6), with Rubisco being saturated by between 5 and 15 mm cytosolic Ci depending on the measurement technique being used.

Although the similarity of properties between our two model species validates the approach of comparing carboxysome properties in vivo, the above findings give very little insight into why cyanobacteria have evolved with two distinct classes of carboxysomes. Phylogenetic studies have indicated that it seems as though β-cyanobacteria evolved first, some 3 billion years ago (Blank and Sánchez-Baracaldo, 2010), and presumably, β-carboxysomes were first developed in this group, although the exact timing of this advent is unclear. The origins of α-cyanobacteria are much more recent (some 0.6 to 1 billion years ago; Blank and Sánchez-Baracaldo, 2010) and presumably arose through HGT of an α-carboxysome operon from proteobacteria. The question arises as to what was the functional advantage of this transfer, which allowed α-cyanobacteria to be ecologically successful, particularly in open ocean marine environments (Badger et al., 2006). A potential answer could be found in the response of α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes to cytosolic Ci, with the possibility that α-carboxysomes have a higher affinity for external Ci, which would allow a reduced investment in Ci transporter components with a savings in energy and nitrogen, both desirable in the oligotrophic ocean. However, this hypothesis is not borne out by the results obtained here.

Broader Implications

The fact that both α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes from freshwater and coastal niches show unexpected similarity in function is relevant to global net primary productivity models, in that these data are, to our knowledge, the first data to provide an insight into the likely carboxysome physiology of cyanobacteria in the open oceans. As mentioned above, oceanic cyanobacteria potentially contribute as much as one-half of oceanic net primary productivity (Liu et al., 1997, 1999; Field et al., 1998) but are characterized as having low-flux photosynthetic rates. Although little data are currently available on the Rubisco kinetics of open ocean α-cyanobacteria, despite the conflicting findings in the work by Scott et al. (2007), our findings suggest that both α-carboxysomes and β-carboxysomes, in the respective cell background, are capable of high-flux photosynthetic rates. However, additional data are required regarding the Ci-uptake kinetics of open ocean α-cyanobacteria before firm conclusions can be made regarding overall CCM function and photosynthetic capability. Nonetheless, we expect carboxysome performance of oceanic strains to be similar to the range of criteria measured here. This result, in turn, has implications for the incorporation of cyanobacterial CCM components into crop species for the enhancement of photosynthesis (Price et al., 2013), because it suggests that both α-carboxysome and β-carboxysome types might provide equal benefits within an engineered CCM. The genetic simplicity of some α-carboxysomes (e.g. Prochlorococcus spp. strains only produce one form of the shell protein CsoS2 [Roberts et al., 2012], and H. neapolitanus carboxysomes can be formed with foreign Rubiscos [Menon et al., 2008]) makes them ideal candidates for incorporation into chloroplasts for enhanced photosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cyanobacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Cells of the cyanobacteria Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. were cultured in modified BG11 medium containing 20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0) at 30°C with a light intensity of approximately 85 µmol photons m−2 s−1. Cultures were vigorously sparged with air enriched with 2% (v/v) CO2 (high-CO2 conditions) or air containing 20 μL L−1 CO2 (low-CO2 conditions).

Mass Spectrometric Measurements

Cells were prepared for mass spectrometry as described previously (Price and Badger, 1989b). Chl was determined after extraction of cells in methanol for 5 min at 21°C for Synechococcus spp. and 70°C for Cyanobium spp. because of the tougher nature of these cells. Cells were assayed at a Chl density between 3 and 15 µg mL−1, depending on the experiment, in a thermostatted (30°C) cuvette at a light intensity of 1,200 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The cuvette was connected to a mass spectrometer (VG Micromass 6) by a membrane inlet. Cells were suspended in BG11 medium buffered with 50 mm 1,3-bis-[tris(hydroxymethyl) methylamino]propane-HCl (pH 7.9), where NaNO3 had been replaced with 20 mm NaCl. Measurements of photosynthetic affinity and metabolites of low-CO2-grown cells were performed in the presence of 30 µg mL−1 carbonic anhydrase. To sample cells at very low Ci concentrations (<30 µm), a perfusion system was used to establish a low but steady-state level of Ci in the cuvette before sampling. To achieve it, a syringe pump was used to deliver a constant supply of NaHCO3 into the cuvette. If it is not done, the Ci constantly changes during the experiments and often runs out because of the high affinity of photosynthesis for external Ci.

Measurements of the 18O exchange reaction between doubly labeled CO2 (13C18O18O) and water were performed as previously described (Maeda et al., 2002). Recording of CO2-labeled masses (49, 47, and 45) was monitored over time. Cells were injected into the cuvette after the addition of NaH13C18O3 (final concentration of 1.5 mm).

Measurements of Ci uptake, efflux, and pool sizes were done as previously described (Badger et al., 1985). Algal suspensions for these experiments were 15 µg Chl mL−1 for high-CO2-grown cells and 3 µg Chl mL−1 for low-CO2-grown cells. All experiments were performed with 30 µg mL−1 of carbonic anhydrase in solution. Initial CO2 uptake was measured in the absence of external carbonic anhydrase. CO2 uptake was assessed by measuring the initial rate of CO2 uptake immediately after the onset of illumination (Badger and Andrews, 1982).

Silicon Oil Centrifugation/Filtration Experiments

To extend the MIMS measurements of internal Ci pool sizes, we conducted measurements of internal Ci pools of high-CO2-grown cells using silicone oil centrifugation. This technique for measuring internal pools potentially avoids underestimates of Ci pools because of continued Rubisco fixation of CO2 in the initial dark period. Accumulation of acid-stable and acid-labile 14C was followed using the silicon oil centrifugation method as described in the work by Kaplan et al., 1980. The time course of 14C uptake was up to 3 min. Experiments were performed at pH 8.0 in BG11 medium described above. A light intensity of 450 µmol photons m−2 s−1 was used. Cells were depleted of Ci before each experiment and used at a Chl density of 4 µg mL−1. Experiments were initiated by the addition of unbuffered NaH14CO3 (pH 8.1–8.2).

The volume of cells grown at low and high CO2 was calculated using the silicon oil centrifugation technique (Kaplan et al., 1980). Experiments compared 14C and 3H labels in pellets incubated in 14C-sorbitol (cell impermeable) and 3H-tritium (cell permeable).

Metabolite Assays

RuBP and PGA pool sizes were determined from actively photosynthesizing cells rapidly killed by the addition of formic acid. Photosynthetic rate and external Ci concentration were measured at a Chl density of 15 µg mL−1. At each Ci concentration, 1 mL of cells was rapidly drawn into a syringe containing formic acid (final concentration of 10% [v/v]). Samples were then dried in a SpeedVac concentrator. The dried pellet was resuspended in 300 µL of extraction medium (methanol:chloroform [3:7, v/v]). After extracting for 60 min at 4°C, the aqueous and lipid fractions were separated by adding 250 µL of water, and the aqueous fraction was collected for analysis. The aqueous fraction was dried in a SpeedVac and resuspended in assay medium of 200 mm 4-2(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine propane sulfonic acid:NaOH (pH 8.2), 25 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm EDTA. Samples were assayed for RuBP and PGA in a 1-mL spectrophotometric assay (Hanson et al., 2003). The assay buffer consisted of assay medium (as above), 100 µm NADH, 5 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm ATP, 4 units of 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, 2.5 units of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 20 units of triose-phosphate isomerase. Metabolites were assayed by the sequential addition of 6 unites of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase for PGA and 150 µg of preactivated spinach (Spinacia oleracea) Rubisco for RuBP.

Electron Microscopy

Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells were cultured as detailed above to a density of approximately 15 µg Chl mL−1; 1 mL of cells was pelleted in an Eppendorf tube, and these pellets were fixed, embedded, and stained as detailed previously (Price and Badger, 1989b).

Extraction and Purification of Rubisco from Cultured Cells

Crude extracts of cultured cells were prepared by bead beating concentrated cell suspensions in extraction buffer of 50 mm 4-2(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine propane sulfonic acid:NaOH (pH 8) and 1 mm EDTA containing protease inhibitor cocktail for bacterial extracts (Sigma). Extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Rubisco protein was purified from Cyanobium spp. cell extracts using the method from the work by Morell et al., 1994 with minor modifications. Cell extracts were not heated before fractionation in saturated ammonium sulfate solution. Samples were applied to a 5-mL Mini-Macroprep High-Q strong anion-exchange cartridge (Bio-Rad) that was preequilibrated with solubilization buffer lacking dithiothreitol and Rubisco eluted with a gradient from 0 to 750 mm NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) and 1 mm EDTA. Running conditions were 5.0 mL min−1 at 4.0°C; 5.0-mL fractions were collected throughout the run. Synechococcus spp. PCC6301 Rubisco protein was purified from an Escherichia coli expression system (Whitney and Sharwood, 2007) and supplied as a gift from Spencer Whitney.

Rubisco Kinetic Measurements

The Km values for RuBP and CO2 were measured in Rubisco protein purified from Cyanobium spp. cell extracts and Synechococcus spp. PCC6301 Rubisco protein purified from E. coli cells. Assay conditions are detailed in the work by Whitney and Sharwood (2007) and are based on 14CO2 incorporation into PGA.

Rubisco Active Site Determinations with CABP

Active site concentrations of Rubisco were measured using the CABP binding method (Whitney and Sharwood, 2007). Active site concentration was measured on a Chl basis using crude cell extracts of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells. Active sites were also measured on a protein basis in purified protein extracts (as detailed above) to calculate the catalytic turnover rate of Rubisco in the two strains.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Cyanobacterial species phylogeny based on Rubisco large subunit (RbcL) protein sequences.

Supplemental Figure S2. The response of RuBP and PGA pools to darkness in Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells grown at high CO2.

Supplemental Figure S3. Exchange of 18O out of labeled CO2 species by Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp. cells grown at high and low CO2.

Supplemental Figure S4. Time courses of Ci accumulation in Synechococcus spp. at high and low external Ci measured by MIMS.

Supplemental Figure S5. Time courses of Ci accumulation in Cyanobium spp. at high and low external Ci measured by MIMS.

Supplemental Figure S6. The modeled response of Rubisco carboxylase rate in an α-carboxysome to external HCO3−.

Supplemental Table S1. The presence of carboxysome and Ci transporters genes in the genomes of Synechococcus spp. and Cyanobium spp.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cathy Gillespie (Microscopy and Cytometry Resource Facility, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Australian National University) for help with electron microscopy preparation, protocols, and imaging.

Glossary

- CCM

carbon-concentrating mechanism

- Chl

chlorophyll

- Ci

inorganic carbon

- h/d

hydration-dehydration ratio

- HGT

horizontal gene transferMIMS: membrane inlet mass spectrometry

- PGA

phosphoglyceraldehyde

- RuBP

ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- O2

oxygen

- KRuBP

dissociation constant of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate

- KCO2

dissociation constant of carbon dioxide

- MIMS

membrane inlet mass spectrometry

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (Discovery Grant to G.D.P. and M.R.B.).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ. (1982) Photosynthesis and inorganic carbon usage by the marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. Plant Physiol 70: 517–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ, Whitney SM, Ludwig M, Yellowlees DC, Leggat W, Price GD. (1998) The diversity and co-evolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids and chloroplast-based CCMs in the algae. Can J Bot 76: 1052–1071 [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Bassett M, Comins HN. (1985) A model for HCO3accumulation and photosynthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp: theoretical predictions and experimental observations. Plant Physiol 77: 465–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Bek EJ. (2008) Multiple Rubisco forms in proteobacteria: their functional significance in relation to CO2 acquisition by the CBB cycle. J Exp Bot 59: 1525–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Gallagher A. (1987) Adaptation of photosynthetic CO2 and HCO3- accumulation by the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC6301 to growth at different inorganic carbon concentrations. Aust J Plant Physiol 14: 189–201 [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Hanson D, Price GD. (2002) Evolution and diversity of CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria. Funct Plant Biol 29: 161–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. (1989) Carbonic anhydrase activity associated with the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Physiol 89: 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. (2003) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J Exp Bot 54: 609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD, Long BM, Woodger FJ. (2006) The environmental plasticity and ecological genomics of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. J Exp Bot 57: 249–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S. (1984) The relationship between steady-state gas exchange of bean leaves and the levels of carbon-reduction-cycle intermediates. Planta 160: 305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C, Knoop H, Axmann IM, Steuer R. (2012) The diversity of cyanobacterial metabolism: genome analysis of multiple phototrophic microorganisms. BMC Genomics 13: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benschop JJ, Badger MR, Dean Price G. (2003) Characterisation of CO2 and HCO3− uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Photosynth Res 77: 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank CE, Sánchez-Baracaldo P. (2010) Timing of morphological and ecological innovations in the cyanobacteria—a key to understanding the rise in atmospheric oxygen. Geobiology 8: 1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cot SS, So AK, Espie GS. (2008) A multiprotein bicarbonate dehydration complex essential to carboxysome function in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol 190: 936–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Williams EB, Murin CD, Shively JM, Cannon GC. (2008) CO2 fixation kinetics of Halothiobacillus neapolitanus mutant carboxysomes lacking carbonic anhydrase suggest the shell acts as a diffusional barrier for CO2. J Biol Chem 283: 10377–10384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlyn-Jones D, Woodger FJ, Price GD, Whitney SM. (2006) RbcX can function as a rubisco chaperonin, but is non-essential in Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1630–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Kimber MS. (2011) Carboxysomes: cyanobacterial RubisCO comes in small packages. Photosynth Res 109: 7–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P. (1998) Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281: 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales AD, Light YK, Zhang ZD, Iqbal T, Lane TW, Martino A. (2005) Proteomic analysis of the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the open-ocean cyanobacterium Synechococcus WH8102. Can J Bot 83: 735–745 [Google Scholar]

- Greene DN, Whitney SM, Matsumura I. (2007) Artificially evolved Synechococcus PCC6301 Rubisco variants exhibit improvements in folding and catalytic efficiency. Biochem J 404: 517–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson DT, Franklin LA, Samuelsson G, Badger MR. (2003) The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cia3 mutant lacking a thylakoid lumen-localized carbonic anhydrase is limited by CO2 supply to rubisco and not photosystem II function in vivo. Plant Physiol 132: 2267–2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassidim M, Keren N, Ohad I, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. (1997) Acclimation of Synechococcus strain WH7803 to ambient CO2 concentration and to elevated light intensity. J Phycol 33: 811–817 [Google Scholar]

- Iancu CV, Ding HJ, Morris DM, Dias DP, Gonzales AD, Martino A, Jensen GJ. (2007) The structure of isolated Synechococcus strain WH8102 carboxysomes as revealed by electron cryotomography. J Mol Biol 372: 764–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL. (1981) Species variation in the specificity of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Nature 291: 513–515 [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Danev R, Nagayama K, Nakamoto H. (2006) Intact carboxysomes in a cyanobacterial cell visualized by hilbert differential contrast transmission electron microscopy. J Bacteriol 188: 805–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Badger MR, Berry JA. (1980) Photosynthesis and the intracellular inorganic carbon pool in the bluegreen alga Anabaena variabilis: response to external CO2 concentration. Planta 149: 219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagouni AD, Bloye SA, Carr NG. (1990) The presence and absence of inorganic carbon concentrating systems in unicellular cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 68: 137–142 [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. (2010) Bacterial microcompartments. Annu Rev Microbiol 64: 391–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Tanaka S, Nguyen CV, Phillips M, Beeby M, Yeates TO. (2005) Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles. Science 309: 936–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JN, Axen SD, Kerfeld CA. (2011) Comparative analysis of carboxysome shell proteins. Photosynth Res 109: 21–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer B, Sültemeyer D, Badger MR, Price GD. (1999) The involvement of NAD(P)H dehydrogenase subunits, NdhD3 and NdhF3, in high-affinity CO2 uptake in Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 gives evidence for multiple NDH-1 complexes with specific roles in cyanobacteria. Mol Microbiol 32: 1305–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupriyanova EV, Sinetova MA, Cho SM, Park YI, Los DA, Pronina NA. (2013) CO2-concentrating mechanism in cyanobacterial photosynthesis: organization, physiological role, and evolutionary origin. Photosynth Res 117: 133–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HB, Landry MR, Vaulot D, Campbell L. (1999) Prochlorococcus growth rates in the central equatorial Pacific: an application of the fmax approach. J Geophys Res Oceans 104: 3391–3399 [Google Scholar]

- Liu HB, Nolla HA, Campbell L. (1997) Prochlorococcus growth rate and contribution to primary production in the equatorial and subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Aquat Microb Ecol 12: 39–47 [Google Scholar]

- Long BM, Badger MR, Whitney SM, Price GD. (2007) Analysis of carboxysomes from Synechococcus PCC7942 reveals multiple Rubisco complexes with carboxysomal proteins CcmM and CcaA. J Biol Chem 282: 29323–29335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long BM, Rae BD, Badger MR, Price GD. (2011) Over-expression of the β-carboxysomal CcmM protein in Synechococcus PCC7942 reveals a tight co-regulation of carboxysomal carbonic anhydrase (CcaA) and M58 content. Photosynth Res 109: 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long BM, Tucker L, Badger MR, Price GD. (2010) Functional cyanobacterial β-carboxysomes have an absolute requirement for both long and short forms of the CcmM protein. Plant Physiol 153: 285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Badger MR, Price GD. (2002) Novel gene products associated with NdhD3/D4-containing NDH-1 complexes are involved in photosynthetic CO2 hydration in the cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Mol Microbiol 43: 425–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo WP, Elrifi IR, Turpin DH. (1989) The relationship between ribulose bisphosphate concentration, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) transport and DIC-limited photosynthesis in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus leopoliensis grown at different concentrations of inorganic carbon. Plant Physiol 90: 720–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon BB, Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Shively JM, Cannon GC. (2008) Halothiobacillus neapolitanus carboxysomes sequester heterologous and chimeric RubisCO species. PLoS ONE 3: e3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon BB, Heinhorst S, Shively JM, Cannon GC. (2010) The carboxysome shell is permeable to protons. J Bacteriol 192: 5881–5886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell MK, Paul K, O’Shea NJ, Kane HJ, Andrews TJ. (1994) Mutations of an active site threonyl residue promote β elimination and other side reactions of the enediol intermediate of the ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase reaction. J Biol Chem 269: 8091–8098 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J, Gutteridge S. (1990) The purification and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies of recombinant Synechococcus ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 265: 15154–15159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD. (2011) Inorganic carbon transporters of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism. Photosynth Res 109: 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR. (1989a) Expression of human carbonic anhydrase in the cyanobacterium Synechoccocus PCC7942 creates a high CO2-requiring phenotype: evidence for a central role for carboxysomes in the CO2 concentrating mechanism. Plant Physiol 91: 505–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR. (1989b) Isolation and characterisation of high CO2-requiring-mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942: two phenotypes that accumulate inorganic carbon but are apparantly unable to generate CO2 within the carboxysome. Plant Physiol 91: 514–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, Woodger FJ, Long BM. (2008) Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J Exp Bot 59: 1441–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Pengelly JJL, Forster B, Du J, Whitney SM, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Howitt SM, Evans JR. (2013) The cyanobacterial CCM as a source of genes for improving photosynthetic CO2 fixation in crop species. J Exp Bot 64: 753–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae BD, Förster B, Badger MR, Price GD. (2011) The CO2-concentrating mechanism of Synechococcus WH5701 is composed of native and horizontally-acquired components. Photosynth Res 109: 59–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD. (2013) Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77: 357–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts EW, Cai F, Kerfeld CA, Cannon GC, Heinhorst S. (2012) Isolation and characterization of the Prochlorococcus carboxysome reveal the presence of the novel shell protein CsoS1D. J Bacteriol 194: 787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Canvin DT. (1997) HCO3- efflux and the regulation of the intracellular Ci pool size in Synechococcus UTEX 625. Can J Bot 75: 290–300 [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya MR, Cannon GC, Heinhorst S, Tanaka S, Williams EB, Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA. (2006) The structure of β-carbonic anhydrase from the carboxysomal shell reveals a distinct subclass with one active site for the price of two. J Biol Chem 281: 7546–7555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Henn-Sax M, Harmer TL, Longo DL, Frame CH, Cavanaugh CM. (2007) Kinetic isotope effect and biochemical characterization of form IA RubisCO from the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus MIT9313. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 2199–2204 [Google Scholar]

- So AKC, Espie GS, Williams EB, Shively JM, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. (2004) A novel evolutionary lineage of carbonic anhydrase (ε class) is a component of the carboxysome shell. J Bacteriol 186: 623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabita FR. (1999) Microbial ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: a different perspective. Photosynth Res 60: 1–28 [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, Fukushima Y, Hara S, Hisabori T. (2013) Redox control of the activity of phosphoglycerate kinase in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Plant Cell Physiol 54: 484–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Coleman JR, Berry JA. (1983) Control of photosynthesis by RuP2 concentration: studies with high- and low-CO2-adapted cells of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Year B Carnegie Inst Wash 95: 91–95 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Edmondson DL. (1986) Relationship between steady-state gas-exchange, in vivo ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase activity and some carbon reduction cycle intermediates in Raphanus sativus. Aust J Plant Physiol 13: 669–688 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Sharwood RE. (2007) Linked Rubisco subunits can assemble into functional oligomers without impeding catalytic performance. J Biol Chem 282: 3809–3818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates TO, Crowley CS, Tanaka S. (2010) Bacterial microcompartment organelles: protein shell structure and evolution. Annu Rev Biophys 39: 185–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.