Abstract

Background: Worldwide, the demand for specialist palliative care is increasing but funding is limited. The role of volunteers is underresearched, although their contribution reduces costs significantly. Understanding what volunteers do is vital to ensure services develop appropriately to meet the challenges faced by providers of palliative care.

Objective: The study's objective is to describe current involvement of volunteers with direct patient/family contact in U.K. specialist palliative care.

Design: An online survey was sent to 290 U.K. adult hospices and specialist palliative care services involving volunteers covering service characteristics, involvement and numbers of volunteers, settings in which they are involved, extent of involvement in care services, specific activities undertaken in each setting, and use of professional skills.

Results: The survey had a 67% response rate. Volunteers were most commonly involved in day care and bereavement services. They entirely ran some complementary therapy, beauty therapy/hairdressing, and pastoral/faith-based care services, and were involved in a wide range of activities, including sitting with dying patients.

Conclusions: This comprehensive survey of volunteer activity in U.K. specialist palliative care provides an up-to-date picture of volunteer involvement in direct contact with patients and their families, such as providing emotional care, and the extent of their involvement in day and bereavement services. Further research could focus on exploring their involvement in bereavement care.

Introduction

Volunteers are integral to palliative care worldwide, including North America,1,2 Europe,3–6 Africa,7 and India.8 Global mortality is predicted to rise by between 14% and 42% from 2002 to 20309 with many deaths following a period of progressive chronic illness increasing demand for palliative care.10 In many countries palliative care is provided in hospices or hospice programs. In the United States there are nearly half a million hospice volunteers,11 and more than 100,000 in the United Kingdom (U.K.),12 where their contribution reduces hospice costs by an estimated 23%.13 U.K. hospice services are specialist palliative care units which typically provide inpatient and day care (a service provided in a hospice building to nonresidents), as well as home-based care.14 Patients with advanced progressive disease are eligible for such care. Services are free to patients (although availability varies across the United Kingdom), with referral usually via health care professionals.

Although many volunteers are involved with fundraising,15 there is increasing global interest in their role in direct care, especially in North America and Europe. 16 Studies have provided a general overview of the volunteer role, including ‘listening and responding,’17 socializing, and enhancing the quality of patients' lives.18 However, published data on what volunteers do are limited, other than a survey of 219 U.K. palliative care services, which provided an overview of the percentages of volunteers involved by care setting,15 and a case study of one U.K. hospice.19 Here it was found that volunteers were involved in inpatient, day care, and home care, and in the provision of bereavement care. Tasks included serving meals to inpatients, helping with diversional activities in day care, providing transport between patients' homes and hospice facilities, and practical help in patients' homes.19 Some people were found to volunteer their professional skills, including chiropodists, hairdressers, and gardeners.19

National surveys help illuminate the bigger picture, allowing knowledge to be shared between countries. They can help focus future research that may enhance practice. To obtain a detailed and up-to-date picture of volunteer activity, we surveyed palliative care services for adults in the United Kingdom, both in the voluntary (services run by charities outside of U.K. statutory, i.e., National Health Service, control) and statutory sectors (both voluntary and statutory U.K. hospices are run on a not-for-profit basis). We focused on volunteers with direct contact with patients and families, rather than on those involved elsewhere, e.g., in fundraising, or as trustees. We aimed to ascertain the full range of volunteer activities, including the extent to which they run care services and whether professionals volunteer their skills. We compared the voluntary and statutory sectors, different sizes and types of service, and settings within services, such as inpatient and home care.

Methods

Informed by previous surveys15,19 we developed a web-based 50-item questionnaire using SurveyMonkey, an Internet data collection service. The questionnaire included questions on service characteristics, involvement and number of volunteers, care settings in which volunteers are involved, the extent of volunteer involvement in specific care services such as physiotherapy and complementary therapies, the specific activities volunteers undertake, and volunteer use of professional skills. Care settings included inpatient care (residential specialist palliative care, which may be for symptom control, or respite or terminal care); day care, where nonresidential patients receive care services available to inpatients including some medical care, and creative and complementary therapies such as art, massage, and aromatherapy; outpatient clinics (clinical care to nonresidential patients); home-based care; and bereavement services. 14 In the U.K. some home care services are termed hospice-at-home. These provide services similar to those available to hospice inpatients.14 The specific activities we asked about mostly related to tasks undertaken by volunteers, but we also asked about ‘giving emotional care’ as a way of including the intrinsic quality of volunteers' contribution. In the questionnaire we suggested that this could mean ‘sitting and listening,’ but we allowed respondents to interpret this in their own way. The survey also included questions on volunteer management, the findings of which will be reported elsewhere. Respondents could add items and comments in free-text boxes at the end of each question. The draft survey was tested inhouse using cognitive pretesting20 to check whether the questions were measuring the constructs we intended, and piloted for appropriateness at four hospices.

We used the directory of palliative care services of a charitable organization to which most U.K. services belong (Help the Hospices),21 to identify specialist palliative care services for adults listed as involving volunteers (290 of 539 services). We e-mailed a contact from each service, typically the volunteer manager/coordinator, a web link to the survey. To enhance response, the survey was publicized in publications and conferences before and during data collection, which lasted one month, from November 9, 2011. We sent a reminder e-mail in the third week. Nonrespondents were first e-mailed, and subsequent nonresponders were telephoned a maximum of two times.

Incomplete responses, and those from respondents who said their organization did not involve volunteers, were removed from the dataset. To check data were representative of U.K. services using volunteers, responders were compared with nonresponders on management status (voluntary or statutory), size of services, and region (data supplied by Help the Hospices). We could not find a definition for size of service, so we used as a proxy measure the median number of inpatient beds (14 beds) in all U.K. palliative care services with beds (including nonresponders and services that do not involve volunteers). Services without beds such as those providing home care or day care only, were categorized separately.

Using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) we analyzed quantitative data using nonparametric descriptive statistics due to highly skewed distributions. For categorical data, comparisons were made using χ2 tests (Fisher's exact test used when one cell was zero), and for scale data, Kruskal-Wallis tests, with statistically significant differences assumed at p-value<0.05. Percentages were based on the number of respondents answering each question and were rounded. Free-text responses were analyzed based on content and frequency of similar responses.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from University College London (UCL) [ID #3077/001; November 1, 2011]. The survey was undertaken by the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Unit (MCPCRU), UCL Medical School, U.K.; the Institute for Volunteering Research (IVR), U.K.; and the International Observatory on End of Life Care, Lancaster University, U.K.

Results

We contacted 290 organizations: 218 voluntary sector services (hospices) and 72 statutory services; 227 (78%) in England, 30 (10%) in Scotland, 28 (10%) in Wales, and 5 (2%) in Northern Ireland. We received 233 responses resulting in evaluable data from 194 hospices and palliative care organizations, a 67% response rate. Of these, 79% (n=153) were voluntary sector services and 21% (n=41) were statutory, with 35% overall (n=72) having 1 to 14 beds, 37% (n=67) 15 or more beds, and 28% (n=55) no beds (hospice at home, or home care or day care only services). Day care was provided by 90% of services and inpatient facilities by 79%, while home care was provided by 71% of services. Twelve respondents combined data for up to three services in one response, where they were responsible for more than one hospice or other service, such as a day care unit. These responses were included in the comparison of responders with nonresponders, and in analyses of all responders, but not in stratified analyses of responders, because some groups included services with different management status or median number of beds (including no beds).

Responders were more likely than nonresponders to be from voluntary-managed services than statutory services (p=0.038) and from England or Scotland than Wales or Northern Ireland (p=0.006). There was no statistically significant difference in rate of response by service size (based on bed numbers).

Involvement and numbers of volunteers

We found, per service, approximately one-and-a-half volunteers for every paid member of staff (including office, care, and clinical staff, excluding ‘bank’ or agency nurses). Voluntary sector services had more paid staff, volunteers overall, and volunteers in direct contact with patients and families than statutory services. Services with no beds had fewer paid staff and volunteers than services with beds. Services with more than 14 beds had more paid staff and volunteers than those with between 1 and 14 beds (see Table 1).

Table 1.

| N cases | Whole dataset | N cases | Statutory services | N cases | Voluntary services | N cases | 0 beds | N cases | 1–14 beds | N cases | >14 beds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paid staff | 154 | 90 (1–485) | 31 | 30 (1–110) | 123 | 96* (2–485) | 41 | 20 (1–172) | 59 | 85 (3–315) | 54 | 120* (48–485) |

| Volunteers | 159 | 167 (1–4300) | 33 | 60 (1–270) | 126 | 200* (7–4300) | 41 | 50 (2–541) | 59 | 200 (1–1000) | 59 | 200* (10–4300) |

| Volunteers with direct patient or family contact | 155 | 85 (1–1110) | 34 | 45 (1–255) | 121 | 99* (2–1110) | 41 | 37 (3–200) | 57 | 80 (1–440) | 57 | 120* (2–1110) |

Office, care, and clinical staff, not ‘bank’ or agency nurses.

Not trustees, fundraisers, or shop workers.

p<0.001 for Kruskal-Wallis test between statutory and voluntary organizations, or between services with 0 beds, 1–14 beds, and >14 beds.

Settings

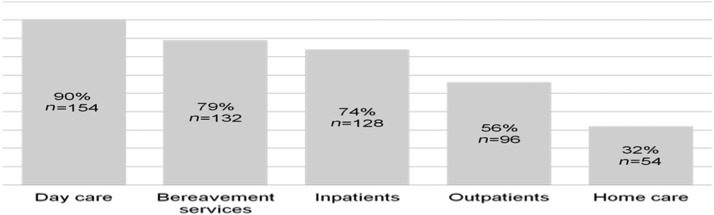

Volunteers were most commonly involved in day care and least commonly in home care (see Figure 1). Compared with statutory sector organizations, voluntary sector services were more likely to involve volunteers in day care (χ2 (1, N=166)=7.14, p=0.008), bereavement services (χ2 (1, N=166)=16.58, p≤0.001), and home care (χ2 (1, N=166)=8.52, p=0.004).

FIG. 1.

Settings where hospices or palliative care services involve volunteers.

Extent of volunteer involvement in care services

Creative/diversional therapies, complementary/alternative therapies, counseling, and pastoral/faith-based services most commonly involved volunteers. Beauty/hairdressing, creative/diversional therapies, complementary/alternative therapies, and pastoral/faith-based services were most commonly run entirely by them. In free-text responses, transport was most commonly cited as being run by volunteers (mentioned by 34 respondents). Services least commonly involving volunteers were social work, physiotherapy/gym and occupational therapy, although one social work service and one physiotherapy/gym service were run entirely by volunteers. Volunteers were more likely to be involved in counseling services, creative/diversional therapies, complementary therapy, and pastoral/faith-based care in voluntary sector organizations than in statutory ones (see Table 2). Organizations with >14 beds involved volunteers more often in pastoral/faith-based care and in social work than services with fewer or no beds (pastoral/faith-based care: 71% of organizations with >14 beds compared with 53% of those with 1 to 14 beds, and 23% of those with no beds, p≤0.001; social work: 21% of organizations with >14 beds compared with 7% of those with 1 to 14 beds, and 7% of those with no beds, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Volunteer Involvement in Care Services

| Care services entirely run by volunteers | Care services involving volunteers (but not entirely run by them) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care servicea | Whole dataset N=166 % (N) | Statutory services N=35 % (N) | Voluntary services N=131 % (N) | Whole dataset N=166 % (N) | Statutory services N=35 % (N) | Voluntary services N=166 % (N) |

| Creative/diversional therapies | 14 (23) | 18 (6) | 14 (17) n.s. | 77 (129) | 61 (20) | 80 (98) |

| Complementary/alternative therapies | 12 (20) | 23 (7) | 11 (13) n.s. | 69 (112) | 47 (14) | 74 (89)* |

| Counseling | 2 (3) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) n.s. | 68 (107) | 48 (14) | 71 (83)* |

| Pastoral/faith-based care | 9 (14) | 0 (0) | 12 (14)* | 60 (95) | 43 (13) | 62 (73)* |

| Clinical/nursing care services | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 N/A | 49 (82) | 28 (8) | 63 (74/131)** |

| Beauty therapy or hairdressing | 25 (41) | 29 (9) | 27 (32) n.s. | 52 (83) | 39 (12) | 53 (63) n.s. |

| Gaining patient/family feedback | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) N/A | 42 (66) | 37 (11) | 44 (50) n.s. |

| Drop-in information service | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) n.s. | 34 (52) | 52 (14) | 30 (33) n.s. |

| Occupational therapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) N/A | 23 (32) | 17 (5) | 24 (27/131) n.s. |

| Physiotherapy/gym | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) n.s. | 17 (26) | 10 (3) | 18 (20) n.s. |

| Social work | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) n.s. | 15 (23) | 11 (3) | 15 (17) n.s. |

Figures stratified on management status do not include services that reported combined data from two or three services where their service is part of a group.

X2 test comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations significant at p≤0.05.

X2 test comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations significant at p<0.001.

N/A, X2 tests not performed, as both cells are 0; n.s., X2 tests comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations not significant.

Specific activities volunteers undertake

Table 3 shows the activities in which volunteers were involved within a range of settings. In most organizations volunteers greeted patients and visitors to the service. Where they were involved with inpatients or day care patients they commonly served meals and drinks. They also gave emotional care to patients (e.g., providing companionship) and, in at least half of the settings, to patients' families. In home care settings, giving emotional care to patients and families was the most common activity. Volunteers sat with patients in the last hours of life in 48% of organizations where volunteers were involved with inpatient care (n=45 voluntary sector, n=12 statutory sector)—numbers do not include cases providing combined responses from more than one service—and in 28% of organizations involving volunteers in patients' homes (n=12 voluntary sector, n=1 statutory sector).

Table 3.

Volunteer Activities by Settinga

| Volunteers working with inpatients | (N) N=128 | Volunteers working with day care patients | (N) N=154 | Volunteers working in patients' homes | % (N) N=54 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serving meals and/or drinks | 90 (115) | Serving meals and/or drinks | 94 (144) | Giving emotional care to patients (e.g., sitting and talking) | 80 (43) |

| Greeting patients and visitors to the hospice or palliative care unit | 86 (110) | Greeting patients and visitors to the hospice or palliative care unit | 92 (141) | Giving emotional care to patients' families | 70 (38) |

| Giving emotional care to patients (e.g., sitting and talking) | 86 (110) | Sharing a hobby or activity with patients (e.g., music or poetry) | 92 (141) | Sharing a hobby or activity with patients (e.g., music or poetry) | 57 (31) |

| Sharing a hobby or activity with patients (e.g., music or poetry) | 75 (96) | Giving emotional care to patients (e.g., sitting and talking) | 90 (138) | Running errands for patients (e.g., shopping or collecting prescriptions) | 54 (29) |

| Giving emotional care to patients' families | 75 (96) | Driving | 86 (132) | Driving | 52 (28) |

| Driving | 73 (94) | Beauty therapy or hairdressing | 68 (104) | Assisting patients with social outings | 46 (25) |

| Beauty therapy or hairdressing | 68 (87) | Assisting patients with social outings | 54 (83) | Escorting patients to hospital appointments | 44 (24) |

| Sitting with patients in the last hours of life | 48 (62) | Giving emotional care to patients' families | 50 (76) | Serving meals and/or drinks | 43 (23) |

| Escorting patients to hospital appointments | 44 (56) | Escorting patients to other hospice facilities (e.g., gym) | 34 (52) | Sitting with patients in the last hours of life | 28 (15) |

| Running errands for patients (e.g., shopping or collecting prescriptions) | 38 (48) | Escorting patients to hospital appointments | 27 (42) | Giving advice and information to patients | 24 (13) |

| Assisting patients with social outings | 31 (39) | Running errands for patients (e.g., shopping or collecting prescriptions) | 23 (36) | Escorting patients to other hospice facilities (e.g., gym) | 20 (11) |

| Giving advice and information to patients | 23 (29) | Giving advice and information to patients | 20 (31) | Beauty therapy or hairdressing | 22 (12) |

| Giving physical care to patients (e.g., turning, lifting, and bathing) | 14 (18) | Giving physical care to patients (e.g., turning, lifting, and bathing) | 7 (4) |

Percentage of hospices/units with volunteers undertaking each activity, ranked by volunteer percentage within setting.

Volunteers offering their professional skills

Volunteers most commonly offering professional skills in their volunteer role were beauty therapists/hairdressers, complementary therapists, and spiritual care workers. Compared with statutory organizations, voluntary sector organizations were more likely to involve beauty therapists/hairdressers and complementary therapists in this way (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Volunteers Offering Professional Skills

| Professional group | Whole dataset N=166 % (N) | Statutory services N=35 % (N) | Voluntary services N=131 % (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complementary therapists | 82 (130) | 69 (20) | 86 (100)* |

| Beauty therapists/hairdressers | 72 (106) | 54 (14) | 75 (82)* |

| Spiritual care workers | 64 (94) | 27 (7) | 72 (79)** |

| Mental health professionals | 42 (59) | 33 (9) | 42 (44) n.s. |

| Nurses (qualified) | 25 (34) | 19 (5) | 26 (27) n.s. |

| Physiotherapists | 15 (20) | 4 (1) | 16 (16) n.s. |

| Doctors | 11 (15) | 4 (1) | 11 (11) n.s. |

| Podiatrists | 10 (13) | 4 (1) | 11 (10) n.s. |

| Social workers | 9 (12) | 4 (1) | 10 (10) n.s. |

| Occupational therapists | 8 (10) | 0 | 8 (8) n.s. |

*χ2 tests comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations significant at p≤0.05.

χ2 test comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations significant at p<0.001.

n.s., χ2 tests comparing statutory organizations with voluntary organizations not significant.

Discussion

Although studies have highlighted the social nature of the palliative care volunteer role,17,18 and the previous largest survey found that volunteers were involved in ‘patient care,’15 we have obtained a more detailed and up-to-date national picture of volunteer activity in U.K. palliative care services.

Volunteer involvement in different settings and care services

Organizations most commonly involve volunteers in day care and bereavement services in dedicated hospice facilities. Earlier research found volunteers commonly involved in day care, but not in bereavement services.15 Although we did not ask what volunteers do in bereavement services, bereavement support can include counseling, befriending, home visiting, telephone contact, and social outings.22 We found that in 68% of organizations volunteers were involved in counseling, which is a highly skilled and emotionally demanding role. Since we found that in 42% of organizations people volunteered professional skills in mental health, it may be the case that some of those involved with counseling were professionals. Hospices are expanding their bereavement services23 and may be doing this with greater involvement of volunteers.

Services involved volunteers less frequently in patients' homes than in other settings. In England, while many people express a preference to die at home, relatively few do so (79% nonhome settings versus 21% home).24 This is despite the U.K. government's aim to enable more people to achieve this preference.10 Evaluations in the international literature of volunteers in home care show that volunteers can successfully support patients and their families at home when a loved one is dying.5,25 In the U.K., a service involving volunteers in home care has shown positive outcomes in initial evaluation.26 This demonstrates the potential for service expansion.

Volunteer activities

Providing emotional care to patients and their families was a common activity, particularly in patient's homes, supporting earlier research.17,18 This is a type of care that volunteers may have more time for than paid staff, and which is important to patients and their families.5 We also found that, in nearly half of organizations where volunteers were involved with inpatients, and in nearly a third of organizations involving volunteers in patients' homes, volunteers sat with patients in the last hours of life. This is an important and emotionally demanding activity which paid staff may also not be funded to do, and demonstrates how much volunteers contribute to core end-of-life care.

Comparison between voluntary and statutory sectors

Voluntary sector services involved volunteers with direct patient and family contact to a greater extent than services in the statutory sector, including having more such volunteers, involving them in a wider range of care services, and having more volunteers offering professional skills. Further research may uncover the reasons for this, but it may be the case that this kind of volunteering is more established in the United Kingdom in the voluntary sector than in the statutory sector. Being independent organizations, voluntary sector services may have more flexibility to involve volunteers.

Study limitations

There were significant differences between responders and nonresponders in two of the three comparative factors, management status and region. A higher proportion of the voluntary sector organizations surveyed responded compared with the proportion of statutory sector services. This may reflect greater motivation to take part within the voluntary sector or it may be because statutory services are often small services based within hospitals which are less likely to have a dedicated volunteer manager. Therefore, the results of our comparison of services by management status should be interpreted cautiously. The response rate varied by region, with a larger proportion of organizations responding in England and Scotland compared with Northern Ireland and Wales. However, regional differences were not a focus of our analysis.

The survey is limited to the U.K. milieu but could act as a benchmark for future evaluations and international comparisons. This is important as palliative care continues to develop globally, with countries at different stages of development able to share ideas.27,28 Of course any development in volunteer services should be undertaken within any accreditation and legal requirements.

As the survey did not cover volunteer or staff hours, it was inappropriate to undertake further analysis based on volunteer or staff numbers.

Conclusions

This comprehensive national survey provides an up-to-date picture of volunteer activity in specialist adult palliative care in a country where palliative care is comparatively well developed. It highlights key areas of volunteer contribution, such as volunteers providing emotional care, as well as suggesting areas for future research, such as understanding more about volunteers' contribution to bereavement care, their support needs, and why volunteers are less involved in statutory services than in voluntary ones.29

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Amanda Wilmot (IVR) for help with survey development; Rachel Bilton, Wendy Halley, Elaine Lynch (Marie Curie Cancer Care, United Kingdom), Nigel Hartley (St. Christopher's Hospice, London, U.K.), Dr. Gillian Horne (Rowcroft Hospice, Torquay, U.K.), Dr. Susan Salt (Trinity Hospice, Blackpool, U.K.) for piloting the draft survey; Dr. Mira Varagunam Vasanthan, Baptiste Leurent (MCPCRU, UCL Medical School, U.K.) for statistical advice; Pamela Young, lay project team member, Dr. Louise Jones (MCPCRU, UCL Medical School, U.K.) for commenting on the draft paper.

Author Disclosure Statement

This study was funded by the Dimbleby Marie Curie Cancer Care Research Fund grant DCMC-RF-11-02. The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Guirguis-Younger M, Grafanaki S: Narrative accounts of volunteers in palliative care settings. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2008;25:16–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry P, Planalp S: Ethical issues for hospice volunteers. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2008;25:458–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Help the Hospices: Making volunteers count. London. www.helpthehospices.org.uk/members/education-training/past-events/conference-2011/posters/making-volunteers-count/?locate=en (last accessed November5, 2012)

- 4.Sabatowski R, Radbruch L, Loick G, Grond S, Petzke F: Palliative care in Germany: 14 years on. Eur J Palliat Care 1998;5:52–55 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luijkx KG, Schols JM: Volunteers in palliative care make a difference. J Palliat Care 2009;25:30–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunder U, Cerv B: Slovenia: Status of palliative care and pain relief. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:233–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack BA, Kirton J, Birakurataki J, Merriman A: 'A bridge to the hospice:' The impact of a community volunteer programme in Uganda. Palliat Med 2011;25:705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santha S: Impact of pain and palliative care services on patients. Indian J Palliat Care 2011;17:24–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathers CD, Loncar D: Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoSMed 2006;3:e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.K. Department of Health: End of life care strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: U.K. Department of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Hospice and Palliative Care Association: National volunteering week. www.nhpco.org/files/public/communications/volunteering-Hospice-Facts.pdf (last accessed September17, 2012)

- 12.Help the Hospices: Volunteering. London. www.helpthehospices.org.uk/getinvolved/volunteering/ (last accessed November5, 2012)

- 13.Help the Hospices: Volunteer value: A pilot survey of UK hospices. London: Help the Hospices, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Help the Hospices: What is Hospice Care? London. http://www.helpthehospices.org.uk/about-hospice-care/what-is-hospice-care/ (last accessed June26, 2013)

- 15.Institute for Volunteering Research: Volunteers in hospices and palliative care 2003: A report of three surveys. Report 1: Survey of hospice volunteer managers/coordinators. Institute for Volunteering Research, London, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris S, Wilmot A, Hill M, Ockenden N, Payne S: A narrative literature review of the contribution of volunteers in end of life care services. Palliat Med 2013;27:428–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brazil K, Thomas D: The role of volunteers in a hospital-based palliative care service. J Palliat Care 1995;11:40–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downe-Wamboldt B, Ellerton ML: A study of the role of hospice volunteers. Hosp J 1985;1:17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitewood B: The role of the volunteer in British palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care 1999;6:44–47 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins D: Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res 2003;12:229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Help the Hospices: Hospice and Palliative Care Directory. United Kingdom and Ireland, 2009–2010. London: Help the Hospices, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payne S: The role of volunteers in hospice bereavement support in New Zealand. Palliat Med 2001;15:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Primrose Hospice: Quality Account 2011–2012. Primrose Hospice. www.nhs.uk/aboutNHSChoices/professionals/healthandcareprofessionals/quality-accounts/Documents/2012/primrose-hospice.pdf (last accessed November5, 2012)

- 24.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Higginson IJ: Local preferences and place of death in regions within England 2010. Cicely Saunders International and National End of Life Care Intelligence Network, London, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGill A, Wares C, Huchcroft S: Patients' perceptions of a community volunteer support program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1990;7:43–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ipsos/MORI: Marie Curie helper service evaluation. www.mariecurie.org.uk/Documents/HEALTHCARE-PROFESSIONALS/commissioning-services/Marie20Curie20Helper20Service20evaluation20Main20Report20-20April202012.pdf (last accessed November5, 2012)

- 27.Gupta HK: Volunteers: The model of India. Thirteenth World Congress of the European Association of Palliative Care; London, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinkova M: Ordinary or peculiar folk? On the role of volunteers in palliative care in Czech Republic. Thirteenth World Congress of the European Association of Palliative Care; London, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill M, Ockenden N, Morris S, Payne S: The future of palliative care: What role for volunteering? Nineteenth Voluntary Sector and Volunteering Research Conference, Sheffield: 2013 [Google Scholar]