Abstract

Background: Accurate prediction of prognosis for cancer patients is important for good clinical decision making in therapeutic and care strategies. The application of prognostic tools and indicators could improve prediction accuracy.

Objective: This study aimed to develop a new prognostic scale to predict survival time of advanced cancer patients in China.

Methods: We prospectively collected items that we anticipated might influence survival time of advanced cancer patients. Participants were recruited from 12 hospitals in Shanghai, China. We collected data including demographic information, clinical symptoms and signs, and biochemical test results. Log-rank tests, Cox regression, and linear regression were performed to develop a prognostic scale.

Results: Three hundred twenty patients with advanced cancer were recruited. Fourteen prognostic factors were included in the prognostic scale: Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) score, pain, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, cachexia, white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin, sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) values. The score was calculated by summing the partial scores, ranging from 0 to 30. When using the cutoff points of 7-day, 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day survival time, the scores were calculated as 12, 10, 8, and 6, respectively.

Conclusions: We propose a new prognostic scale including KPS, pain, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, cachexia, WBC count, hemoglobin, sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP values, which may help guide physicians in predicting the likely survival time of cancer patients more accurately. More studies are needed to validate this scale in the future.

Introduction

Accurate prediction of prognosis for cancer patients is important for good clinical decision making in therapeutic and care strategies, and for minimizing risks of undertreatment or overtreatment. Moreover, such information may ease the transition from active medical therapies to palliative-oriented therapies. At present, accurate prognostication remains a challenge even for experienced clinicians. Previous studies have shown the high bias in predicting the prognosis of cancer patients.1–2 A meta-analysis showed that clinicians' survival prediction was overestimated by at least 4 weeks in 27% of cases.3 It is necessary to develop new methods to enhance the clinical prediction of survival. Recent research suggests that repeated assessment of patients over time and with the application of prognostic tools and indicators improves prediction accuracy.4–7

Some studies have identified prognostic factors in cancer patients, and have developed prognostic tools. Performance status (PS) has been recognized in many studies as an important predictor of oncologic outcomes.4,6,8 Clinical symptoms and signs such as anorexia, dysphagia, weight loss, cognitive impairment, and dyspnea seemed to be reliable prognostic factors.5–6,9–12 In a review of prognostic factors, Chow et al.4 reported performance status to be strongly correlated with survival, followed by anorexia, weight loss, and dysphagia found in “terminal syndrome.” Quality of life (QOL) has been shown as a prognostic factor in some studies13–14. Biologic parameters such as leukocytosis,15–16 lymphocytopenia,15–16 C-reactive protein,17–18 low pseudocholinesterase levels,15 high levels of vitamin B12,19 and high bilirubin levels,6 have also been found to be associated with cancer patients' survival. Other factors, for example, patients' marital status, geographic location, and socioeconomic status, may be possible prognostic factors for patients with advanced cancers.20 Various environmental considerations21 were considered as possible prognostic factors for these patients. Based on these prognostic factors, prognostic tools were developed for cancer patients. Morita and colleagues22 developed a scoring system, the Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI), to predict 3- and 6-week survival, with a sensitivity and specificity of more than 70%. Chuang and co-workers23 constructed a prognostic scale, the Cancer Prognostic Scale (CPS), to predict short-term survival of 1 to 2 weeks. Bozcuk et al.24 developed a prognostic tool, the Intrahospital Cancer Mortality Risk Model, to predict the probability of intrahospital death at the time of hospitalization. Schonwetter and colleagues25 constructed a lung cancer-specific prognostic tool, the Lung Cancer Prognostic Model, to predict 50% and 90% mortality in days after admission to a hospice.

Palliative care is a relatively new and developing specialty in China. In our opinion, an important initial step in developing palliative care across China is to establish the referral criteria for hospice care. In doing so, the prediction of survival time, such as 3 or 6 months, is crucial. More accurate prediction could guide physicians about when to recommend hospice care to patients. The prevalence of cancer is high in China, with more than 3 million cancer patients, and it is also the top cause of death in urban residents, indicating that cancer patients would be major service users of palliative care in China. Our group has been engaging in constructing an accessible and valid prognostic tool for hospice/palliative care among advanced cancer patients. Our prior study26 identified prognostic factors and integrated them into a predictive scale for Chinese advanced cancer patients (ChPS) through a retrospective case analysis approach. However, there were some limitations in the ChPS Scale; for example, it didn't involve biologic parameters. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to develop a new prognostic scale for ChPS (new-ChPS Scale) by a prospective survey on the prognostic factors.

Methods

Patients

Patients enrolled had to meet the following criteria: (1) diagnosed as having cancer; (2) death was anticipated within 6 months by doctors and nurses; (3) 18 years or older; (4) able to clearly express feelings and thoughts without serious cognitive impairment diseases or symptoms; (5) consented to participate in the study. A total of 320 advanced cancer patients were enrolled. Patients who were receiving molecular targeted therapy or who were too ill to participate in the study were excluded. All the included patients were prospectively observed after 7 days of hospital admission. The participants were followed up to death as possible.

Data collection

The demographic information was collected including age, sex, marital status, education background, chronic diseases, disclosure of the disease, and economic condition. Patient's performance status was assessed using the Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS), which has been translated into Chinese. QOL was assessed using the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL). MQOL has been widely used to measure palliative patients' QOL. The MQOL was translated into Chinese and psychometric tested in Hong Kong and Taiwan. We used the MQOL-Taiwan version after consulting its developer, S. Robin Cohen, PhD, and getting her permission. Eleven experts in psychology, palliative/hospice care, cancer treatment, and cancer care fields were invited to evaluate the cultural adaptation through group discussion. Revisions were made to some Chinese characters, which they considered difficult to understand for people in the Chinese mainland. Data were collected at the point of recruitment. The participants were asked to complete the MQOL themselves.

We had investigated and identified some variables by a retrospective case analysis approach in our prior study. The common symptoms and signs in the retrospective case study26 were investigated including pain, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal distension, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, dehydration, insomnia, delirium, anorexia, xerostomia, oral ulcer, wound/ulcer, bleeding, fever, dysphagia, numbness, dizziness, weight loss, pallor, fatigue, cachexia, cough, urinary retention, jaundice, palpitation, fecal incontinence, and urinary incontinence. Patients were asked about the presence or absence of self-perceived symptoms (0, absence; 1, presence). The other objective symptoms and signs were assessed by the doctors and the nurses (0, absence; 1, presence). These included ascites, hydrothorax, edema, dehydration, delirium, weight loss, pallor, cachexia, and jaundice.

Previous studies have found some biologic parameters were important predictors of survival such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), white blood cell (WBC) count, lymphocytes count, and bilirubin.6,16,24,26,32 In terms of these studies, we chose three groups of biologic parameters: indexes of routine blood test, indexes of renal function, and indexes of liver function. The following biochemical parameters were recorded: WBC count, red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin, platelets, urea, creatinine, chlorine, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum glucose, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, serum total protein, serum albumin, serum globulin, ratio of serum albumin to serum globulin, gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.1.3 (Statistics Analysis System version 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Survival time was measured in days from the date of investigation to the date of participants' death. Results from patients who were alive at the end of the one-year follow-up period were treated as censoring data and also included in the following analyses.

All analyses followed five steps. First, categorize the KPS score and QOL score. KPS score was categorized as 10–20, 30–40, 50–60, and 70 or more (Table 1). The QOL score was similarly combined to establish three levels, that is, 0–3, 4–6, and 7–10 (Table 1). Second, identify the prognostic factors. The survival curve of each variable in the data was compared by log-rank test to evaluate its association with survival. Variables with p<0.05 were considered putative prognostic factors and included in the multivariate analysis (Table 2). The Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was calculated in the variables to examining for multicollinearity. Then, the Cox regression model was applied in the multivariate analysis. Bootstrap-stepwise procedures were followed. The survival intervals were used as the dependent variable, and the variables selected in the second step were entered in the equation in a backward stepwise fashion. Variables with p<0.25 entered the Cox regression model and were considered as prognostic factors (Table 3). Third, the partial score value was defined as the nearest integer of the quotient obtained by dividing each regression coefficient of a significant prognostic factor by the smallest one in the multivariate analysis (Table 4). The total score of the prognostic scale was calculated by summing the partial scores for each case. Fourth, build the linear regression model between “ln survival time” and the score. “Ln survival time” was the independent variable, and the score was the dependent variable. Then, the cutoff points were determined for survival prediction. Fifth, compare the survival curves of five groups; the curves identified by the new-ChPS Scale were compared by log-rank test.

Table 1.

The Characteristics, KPS Score, and QOL Score of Patients (n=320)

| Items | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age(in years) | ||

| <60 | 118 | 36.9 |

| ≥60 | 202 | 63.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 176 | 55.0 |

| Female | 144 | 45.0 |

| Education background | ||

| No formal education | 30 | 9.4 |

| Primary school | 100 | 31.2 |

| Junior high school | 103 | 32.2 |

| High school | 53 | 16.6 |

| University and above | 34 | 10.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 9 | 2.8 |

| Married | 290 | 90.6 |

| Divorced, separation, spouse dead, and other | 21 | 6.6 |

| Economic burden of treatment | ||

| No and little | 160 | 50.0 |

| Moderate | 131 | 40.9 |

| Heavy | 29 | 9.1 |

| Chronic diseases | ||

| Yes | 113 | 35.3 |

| No | 207 | 64.7 |

| Disclosure of the disease | ||

| Fully | 56 | 17.5 |

| Partly | 107 | 33.4 |

| A little | 114 | 35.6 |

| Not at all | 43 | 13.5 |

| KPS Score | ||

| 10–20 | 52 | 16.2 |

| 30–40 | 128 | 40.0 |

| 50–60 | 103 | 32.2 |

| ≥70 | 37 | 11.6 |

| QOL (MQOL Score) | ||

| 0–3 | 110 | 34.4 |

| 4–6 | 174 | 54.4 |

| 7–10 | 36 | 11.2 |

KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; MQOL, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire; QOL, quality of life.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis Results of Factors and Survival Time by Log-Rank Test

| Factors | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.6097 | 0.4349 |

| Gender | 2.0281 | 0.1544 |

| Education background | 6.0026 | 0.1115 |

| Marital status | 1.1170 | 0.5721 |

| Economic burden of treatment | 3.0064 | 0.2224 |

| Diagnosis | 12.2791 | 0.4235 |

| Chronic disease | 0.3950 | 0.5297 |

| Understanding the condition of disease | 8.6896 | 0.0337* |

| KPS | 86.7645 | <0.0001* |

| QOL (MQOL) | 32.1897 | <0.0001* |

| Pain | 13.1467 | 0.0003* |

| Nausea | 4.9467 | 0.0261* |

| Vomiting | 8.5901 | 0.0034* |

| Dyspnea | 20.7313 | <0.0001* |

| Constipation | 0.2875 | 0.5918 |

| Diarrhea | 0.4225 | 0.5157 |

| Abdominal distension | 4.7348 | 0.0296* |

| Ascites | 9.7375 | 0.0018* |

| Hydrothorax | 13.0140 | 0.0003* |

| Edema | 9.8396 | 0.0017* |

| Dehydration | 1.4063 | 0.2357 |

| Insomnia | 0.1217 | 0.7272 |

| Delirium | 46.4259 | <0.0001* |

| Anorexia | 0.1880 | 0.6646 |

| Xerostomia | 0.4270 | 0.5134 |

| Oral ulcer | 6.2199 | 0.0126* |

| Wound/ulcer | 7.8912 | 0.0050* |

| Bleeding | 2.1921 | 0.1387 |

| Fever | 0.2183 | 0.6403 |

| Dysphagia | 1.2141 | 0.2705 |

| Numbness | 0.1464 | 0.7020 |

| Dizziness | 6.3466 | 0.0118* |

| Loss of weight | 1.8736 | 0.1711 |

| Pallor | 5.4665 | 0.0194* |

| Fatigue | 6.4402 | 0.0112* |

| Cachexia | 49.1238 | <0.0001* |

| Cough | 0.6579 | 0.4173 |

| Urinary retention | 5.5780 | 0.0182* |

| Jaundice | 22.6488 | <0.0001* |

| Palpitation | 1.2877 | 0.2565 |

| Fecal incontinence | 11.6016 | 0.0007* |

| Urinary incontinence | 15.6149 | <0.0001* |

| WBC count | 12.7744 | 0.0004* |

| RBC count | 11.9082 | 0.0006* |

| hemoglobin | 14.0766 | 0.0002* |

| Platelet count | 2.7498 | 0.0973 |

| Urea | 7.4438 | 0.0064* |

| Creatinine | 2.2669 | 0.1322 |

| Serum sodium | 9.5639 | 0.0020* |

| Serum potassium | 7.3285 | 0.0068* |

| Serum chlorine | 0.0003 | 0.9866 |

| Serum glucose | 5.7812 | 0.0162* |

| Total bilirubin | 12.2946 | 0.0005* |

| Direct bilirubin | 8.8186 | 0.0030* |

| Serum total protein | 5.7485 | 0.0165* |

| Serum albumin | 15.5760 | <.0001* |

| Serum globulin | 3.6848 | 0.0549 |

| Ration of albumin to globulin | 12.9805 | 0.0003* |

| GGT | 9.1457 | 0.0025* |

| ALT | 13.1704 | 0.0003* |

| AST | 12.1601 | 0.0005* |

| ALP | 16.9609 | <0.0001* |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; MQOL, McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire; QOL, quality of life; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

p<0.05.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis Results of Factors and Survival Time by Cox Stepwise Regression Model

| Factors | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|

| KPS | ||

| 10–20 | 14.4381 | 0.0001 |

| 30–40 | 5.1429 | 0.0233 |

| 50–60 | 1.3734 | 0.2412 |

| Pain | 3.7334 | 0.0533 |

| Ascites | 3.2302 | 0.0723 |

| Hydrothorax | 2.7225 | 0.0989 |

| Edema | 4.7064 | 0.0300 |

| Delirium | 7.6379 | 0.0057 |

| Cachexia | 9.8195 | 0.0017 |

| WBC count | 1.8713 | 0.1713 |

| Hemoglobin | 8.3135 | 0.0039 |

| Serum sodium | 2.2851 | 0.1306 |

| Total bilirubin | 5.9866 | 0.0144 |

| Direct bilirubin | 2.2339 | 0.1350 |

| AST | 1.9891 | 0.1584 |

| ALP | 3.7132 | 0.0540 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; WBC, white blood cell.

Table 4.

Partial Scores of the Prognostic Scale

| Factors | Regression coefficient | Standard error | Partial score |

|---|---|---|---|

| KPS | |||

| 10–20 | 1.0916 | 0.28728 | 6 |

| 30–40 | 0.54759 | 0.24146 | 3 |

| 50–60 | 0.27659 | 0.23601 | 1 |

| ≥70 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pain | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | 0.29848 | 0.15448 | 2 |

| Ascites | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | −0.29639 | 0.16491 | 1 |

| Hydrothorax | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | 0.26639 | 0.16145 | 1 |

| Edema | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | 0.29923 | 0.13793 | 2 |

| Delirium | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | 0.44507 | 0.16104 | 2 |

| Cachexia | |||

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

| Present | 0.48903 | 0.15606 | 2 |

| WBC count | |||

| Normal (4.0–10.0×109/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (>10.0×109/L; < 4.0×109/L) |

0.19782 | 0.14461 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin | |||

| Normal (Male:120–160 g/L; Female:110–150 g/L) |

0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (Male: <120 g/L; Female: <110 g/L) |

0.43019 | 0.1492 | 2 |

| Sodium | |||

| Normal (134–147 mmol/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (<134 mmol/L, >147 mmol/L) |

0.21922 | 0.14502 | 1 |

| Total bilirubin | |||

| Normal (2–18 μmol/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (>18 μmol/L) | 0.4855 | 0.19843 | 2 |

| Direct bilirubin | |||

| Normal (<7μmol/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (≥7μmol/L) | –0.29821 | 0.19952 | 2 |

| AST | |||

| Normal (<40 u/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (≥40 u/L) | 0.21315 | 0.15113 | 1 |

| ALP | |||

| Normal (32–92 u/L) | 0 | 0 | |

| Not normal (>92 u/L) | 0.27839 | 0.14447 | 1 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Scale; WBC, white blood cell.

Results

A total of 320 consecutive hospitalized patients with advanced cancers were enrolled between October 2008 and May 2010 from 12 hospitals in Shanghai. One hundred seventy-six of them (55.0%) were men, and 144 (45.0%) were women. The median survival time was 34.5 days. With regard to KPS evaluation, patients with a score of 30–40 constituted the largest patient group (128, 40.0%), followed by the 50–60 group (103, 32.2%), the 10–20 group (52, 16.2%), and the >70 group (37, 11.6%). Table 1 summarizes the patients' demographic characteristics.

Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis

The results of univariate analysis are listed in Table 2. KPS, disclosure of the disease, QOL, pain, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, abdominal distension, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, oral ulcer, wound/ulcer, dizziness, pallor, fatigue, cachexia, urinary retention, jaundice, fecal incontinence, urinary incontinence, WBC count, RBC count, hemoglobin, urea, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum glucose, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, serum total protein, serum albumin, ratio of serum albumin to serum globulin, GGT, ALT, AST, and ALP were significantly associated with survival time. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficients in most variables were <0.4 (ranging from <0.001 to 0.393). The others ranged from 0.407 to 0.728. The Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between total bilirubin and direct bilirubin was highest (0.728). The results showed that there were not highly linear correlations in the variables (r<0.9). KPS, pain, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, cachexia, WBC count, hemoglobin, serum sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP were significant factors for survival time by multivariate Cox stepwise regression analysis (Table 3).

Prognostic scale

We used the prognostic factors to construct the prognostic scale. The partial score value was defined as the nearest integer of the quotient obtained by dividing each regression coefficient of a significant prognostic factor by the smallest one in the multivariate analysis. Table 4 shows the partial score value for each category. The total score was calculated for each case by summing the partial scores, ranging from 0 (no altered variables) to 30 (maximal altered variables). The new-ChPS Scale was constructed by linear regression analysis between “ln survival time” and the score. The proposed model is as follows:

|

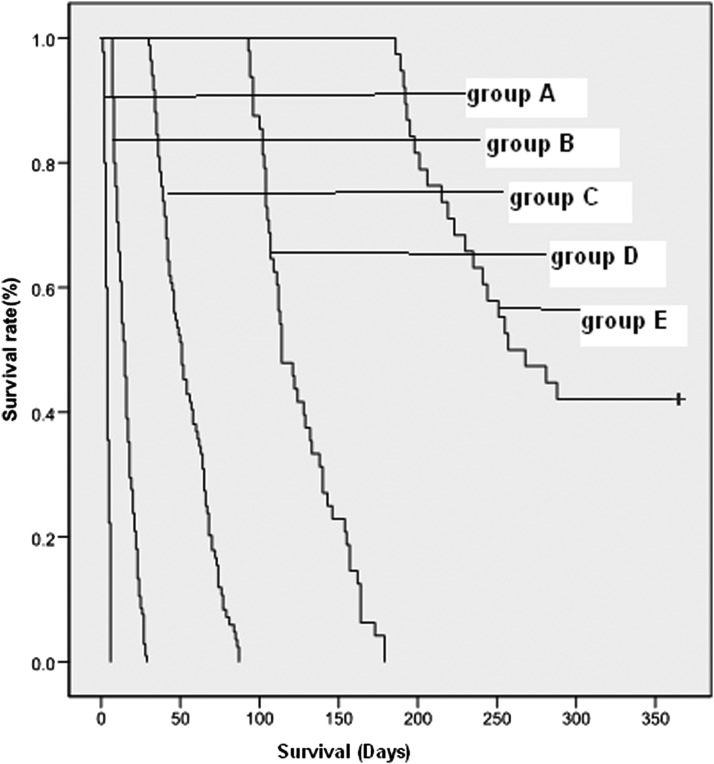

When giving the cutoff points of 7-day, 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day survival time, the scores were 12 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.6–12.7), 10 (95% CI: 9.1–9.9), 8 (95% CI: 7.1–8.0), and 6 (95% CI: 5.7–6.8), respectively. When the prognostic score of a patient was more than 12, the prediction of survival appeared to be <7 days. When the prognostic score of a patient was <6, the prediction of survival appeared to be >180 days (6 months). Figure 1 shows the survival curves of five groups identified by the new-ChPS Scale: Group A (score >12; prediction of survival: <7 days),Group B (score=11 or 12; prediction of survival: 7 to 30 days), Group C (score=9 or 10; prediction of survival: 30 to 90 days),Group D (score=7 or 8; prediction of survival: 90 to 180 days), and Group E (score ≤6; prediction of survival: 180 to 365 days). The log-rank test results were: χ2=840.616, p<0.0001. There were significant differences in survival time among the five groups.

FIG. 1.

Survival curves of five groups identified by the new Chinese Prognostic Scale.

Discussion

The present study identified prognostic factors and developed a prognostic scale by survey of 320 Chinese terminal cancer patients. Fourteen prognostic factors were identified by univariate analysis and multivariate analysis: KPS, pain, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, cachexia, WBC count, hemoglobin, sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP value. By summing the partial scores of patients, the prognostic scale can predict 7-day, 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day survival time, respectively.

Previously published data on prognostic factors proved useful to improve the prediction of cancer patients' survival. KPS was often used to assess cancer patients' performance status. Studies showed that performance status together with some clinical symptoms and mental status could guide the physician in predicting survival of terminal cancer patients.4,21,27 Some symptoms, such as anorexia, weight loss, cachexia, xerostomia, dysphagia, dyspnea, cognitive failure, and delirium5–6,9–12 have been consistently revealed as useful prognostic factors in patients with advanced cancer. In addition, others, including nausea, constipation, dizziness, fever, pain, and diarrhea, have been indicated as prognostic factors in some studies.2,4,21,28–29 Similarly, our new Chinese prognostic scale also included KPS and some important symptoms as the variables. This was consistent with other prognostic scale studies, which all recommended KPS to be an important factor in the prognostic scale.16,21,30 Similar to Pirovano et al.'s study,16 KPS was categorized into score groups of 10–20, 30–40, 50–60, and 70 or more. Six symptoms determined in this study, including pain, ascites, hydrothorax, edema, delirium, cachexia. Cachexia and delirium are generally considered as late-stage predictors of survival.22,31 Pain has also been indicated but not confirmed as a prognostic factor.4,21,28 However, similar to Schonwetter and co-workers' study,25 it was indicated as an important prognostic factor in our study group. Unlike the other symptoms, ascites, hydrothorax, and edema have been less frequently identified as prognostic factors. Several prediction scales included these symptoms. The CPS developed by Chuang and colleagues23 included ascites and edema in the scale. And they also thought that the edema was often iatrogenic and caused by excessive artificial fluid supplementation.23 In addition, in the process of developing the PPI,22 edema was also included. Similarly, ascites was included in our scale. This may because hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the major causes of deaths on the Chinese mainland and ascites is one of the most common symptoms of hepatocellular carcinoma. However, there has been no prognostic scale including hydrothorax as the factor in previous studies. In our opinion, ascites, hydrothorax, and edema may imply the electrolyte-balance imbalance and acid-base imbalance in patients, which might be important factors in predicting the survival time of advanced cancer patients. This issue needs further study.

Unlike our previous study of ChPS,26 the new prognostic scale involved some biologic parameters including WBC count, hemoglobin, sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP value reflecting organic function. It's common to adopt biologic parameters in predicting patients' survival time. Some of these have been recognized as important factors influencing patients' survival time. Hemoglobin and LDH were important predictors of survival in the Interhospital Cancer Mortality Risk Model (ICMRM).24 And WBC count and lymphocytes count were important predictors of survival in the Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP).16 Considering the meaning of the seven biologic parameters in our prognostic scale, they could be categorized into three groups. WBC count and hemoglobin are indexes of routine blood test, indicating general changes of blood. Sodium value is one of indicators that reflect patients' renal function status, and total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP values are a group of indicators that indicate patients' liver function. The results were in accordance with our hypothesis that the changes of some biologic parameters correlated with patients' survival time. Previous studies also supported the results. Rosenthal et al.6 reported that bilirubin rise was significantly related to patients' survival time. Serum sodium and ALP were also thought to be independent factors in predicting survival time of patients with small cell lung cancer.32 Total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP are parameters reflecting liver function. As an important organ, the liver's function status is an important factor in patients' prognosis. However, sodium, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, AST, and ALP value were not included in other prognostic scales. Their significance in survival prediction warrants further study.

In summary, the prognostic scale developed in the present study consisted of KPS, symptoms and signs, and biologic parameters, which were reported as the patient-related indicators of Glare's systematic review.21 Although we collected some tumor-related indicators such as diagnosis and some environment-related indicators such as marital status and economic status, the results didn't include these two kinds of indicators. Tumor-related factors33–34 were shown to be important to advanced cancer patients' survival time, but less important to survival prediction of terminal cancer patients. Environment-related factors35–37 were considered independently in predicting patients' survival time in some studies. However, these factors were not included in the prognostic factors of this study. Considering the reason, environment-related factors might be influenced by culture, geography, and so on. The differences in culture between China and Western countries might lead to different results.

Prognostication is a complex process, which is often influenced by a wide range of factors such as individual characteristics, environment, disease, and care settings. Doctors and nurses should be aware that a prognostic tool is only a guide to help increase the accuracy of prediction. Such tools are not intended to be used slavishly or in a “black-and-white” manner. It is important to remember that every patient is unique, and we can only observe and not decide their exact end of life.38 Nonetheless, the use of a prognostic tool with an integrated score can be helpful. A validation study of a Pneumonia Prognostic Index carried out on a population of 14,199 patients highlighted the need for a tried and tested tool to be “used in conjunction with, rather than in the place of, physician judgment.”39 The new-ChPS Scale achieved this aim by incorporating physician judgment, corrected and integrated with a series of other objective parameters, into the framework of the score itself. We think it is possible to use the new-ChPS Scale to guide physicians in predicting more accurately the likely survival time of cancer patients, which can help doctors and nurses to make appropriate care planning and help patients and their families to participate in the decision-making process.

Limitations

Our study had some limitation. We developed the scale by analyzing 320 cases and tested its validation. However, the accuracy and validation of the scale should be tested in future studies. Besides, our study had the same limitation in generalizability as that of previous studies. Variability in the inclusion of predictors for analysis and the lack of a representative inception cohort decreased the generalizability of many previous results. Because the degree of hospice and palliative care varies around the world, it is difficult to include a representative population at similar and specific points during the course of patients' terminal illness. The conclusion from one study population might not be applicable to other populations with different malignancies and different lengths of survival. More studies are needed to validate the tool and demonstrate its usefulness in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the investigators in the 12 hospitals of the survey. The collaboration of all the participants in the study was also valuable and cherished.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.70973136).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Chritakis NA, Lamont EB: Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognosis in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000;230:469–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viganó A, Dorgan M, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor ME: The relative accuracy of the clinical estimation of the duration of life for patients with end of life cancer. Cancer 1999;86:170–176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hudson M, Eychmuller S, Simes J, Christakis N: A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327:195–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow E, Harth T, Hruby G, Finkelstein J, Wu J, Danjoux C: How accurate are physicians' clinical predictions of survival and the available prognostic tools in estimating survival times in terminally ill cancer patients? A systematic review. Clin Oncol 2001;13:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy JR, Turner R, Saunders M, A'Hern R: Prediction of survival in a hospital-based continuing care unit. 1994;Eur J Cancer 30A:284–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenthal MA, Gebski VJ, Kefford RF, Stuart-Harris RC: Prediction of life expectancy in hospice patients: Identification of novel prognostic factors. Palliat Med 1993;7:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow E, Abdolell M, Panzarella T, Harris K, Bezjak A, Warde P, et al. : Predictive model for survival in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5863–5869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatnagar S, Mishra S: Determining prognosis in patients with advanced incurable cancer. Indian J Med Paed Oncol 2006;27:19–20 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh D, Rybicki L, Nelson KA, Donnelly S: Symptoms and prognosis in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:385–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allard P, Dionne A, Potvin D: Factors associated with length of survival among 1081 terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care 1995;11:20–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruera E, Miller MJ, Kuehn N, MacEachern T, Hanson J: Estimate of survival of patients admitted to a palliative care unit: A prospective study. J Pain Symptom Manage 1992;7:82–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knaus WA, Harrell FE, Lynn J, Goldman L, Phillips RS, Connors AF, Dawson NV, Fulkerson WJ, Califf RM, Desbiens N, Layde P, Oye RK, Bellamy PE, Hakim RB, Wagner DP: The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shadbolt B, Barresi J, Craft P: Self-rated health as a predictor of survival among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2514–2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langendijk H, Aaronson NK, de Jong JM, et al. : The prognostic impact of quality of life assessed with the EORTC QLQ C-30 in inoperable non-small cell lung carcinoma treated with radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2000;55:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maltoni M, Pirovano M, Nanni O, Marinari M, Indelli M, Gramazio A, Terzoli E, Luzzani M, De Marinis F, Caraceni A, Labianca R: Biological indices predictive of survival in 519 Italian terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pirovano M, Maltoni M, Nanni O, Marinari M, Indelli M, Zaninetta G, Petrella V, Barni S, Zecca E, Scarpi E, Labianca R, Amadori D, Luporini G: A new palliative prognostic score: a first step for the staging of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillan DC, Elahi MM, Sattar N, Angerson WJ, Johnstone J, McArdle CS: Measurement of the systemic inflammatory response predicts cancer-specific and non-cancer survival in patients with cancer. Nutr Cancer 2001;41:64–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott HR, McMillan DC, Forrest LM, Brown DJF, McArdle CS, Milroy R: The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2002;87:264–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geissbuhler P, Mermillod B, Rapin CH: Elevated serum vitamin B12 associated with CRP as a predictive factor of mortality in palliative care cancer patients: a prospective study over five years. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000;20:93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwashyna TJ, Zhang JX, Lauderdale DS, Christakis NA: A methodology for identifying married couples in Medicare data: Mortality, morbidity, and health care use among the married elderly. Demography 1998;35:413–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glare P: Clinical predictors of survival in advanced cancer. J Support Oncol 2005;3:331–339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S: The palliative prognostic index: A scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 1999;7:128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang RB, Hu WY, Chiu TY, Chen CY: Prediction of survival in terminal cancer patients in Taiwan: Constructing a prognostic scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;28:115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozcuk H, Koyuncu E, Yildiz M, Samur M, Ozdogan M, Artaç M, Coban E, Savas B: A simple and accurate prediction model to estimate the intrahospital mortality risk of hospitalised cancer patients. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schonwetter RS, Robinson BE, Ramirez G: Prognostic factors for survival in terminal lung cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:356–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou LJ, Cui J, Lu J, Wee B, Zhao JJ: Prediction of survival time in advanced cancer: A prognostic scale for Chinese patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang SS, Scott CB, Chang VT, Cogswell J, Srinivas S, Kasimis B: Prediction of survival for advanced cancer patients by recursive partitioning analysis: Role of Karnofsky Performance Status, quality of life, and symptom distress. Cancer Invest 2004;22:678–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maltoni M, Caraceni A, Brunelli C, Broeckaert B, Christakis N, Eychmueller S, Glare P, Nabal M, Viganò A, Larkin P, De Conno F, Hanks G, Kaasa S; Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care: Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: Evidence-based clinical recommendations—a study by the steering committee of the European Association for Palliative Care: J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6240–6248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viganó A, Bruera E, Jhangri GS, Newman SC, Fields AL, Suarez-Almazor ME: Clinical survival predictors in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glare P, Virik K: Independent perspective validation of the PaP score in terminally ill patients referred to a hospital-based palliative medicine consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S: Improved accuracy of physicians' survival prediction for terminally ill cancer patients using the palliative prognostic index. Palliat Med 2001;15:419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerny T, Blair V, Anderson H, Bramwell V, Thatcher N: Pretreatment prognostic factors and scoring system in 407 small-cell lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer 1987;39:146–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faris M: Clinical estimation of survival and impact of other prognostic factors on terminally ill cancer patients in Oman. Support Care Cancer 2003;11:30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llobera J, Esteva M, Rifà J, Benito E, Terrasa J, Rojas C, Pons O, Catalán G, Avellà A: Terminal cancer: duration and prediction of survival time. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:2036–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forster LE, Lynn J: The use of physiologic measures and demographic variables to predict longevity among inpatient hospice applicants. Am J Hosp Care 1989;6:31–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasanisi F, Orban A, Scalfi L, Alfonsi L, Santarpia L, Zurlo E, Celona A, Potenza A, Contaldo F: Predictors of survival in terminal-cancer patients with irreversible bowel obstruction receiving home parenteral nutrition. Nutrition 2001;17:581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitetta L, Kenner D, Kissane D, Sali A: Clinical outcomes in terminally ill patients admitted to hospice care: Diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. J Palliat Care 2001;17:69–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau F, Cloutier-Fisher D, Kuziemsky C, Black F, Downing M, Borycki E, Ho F: A systematic review of prognostic tools for estimating survival time in palliative care. J Palliat Care 2007;23:93–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fine MJ, Singer DE, Hanusa BH, Lave JR, Kapoor WN: Validation of a pneumonia prognostic index using the Medisgroups Comparative Hospital Database. 1993;Am J Med 94:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]