Abstract

Self-help support groups are indigenous community resources designed to help people manage a variety of personal challenges, from alcohol abuse to xeroderma pigmentosum. The social exchanges that occur during group meetings are central to understanding how people benefit from participation. This paper examines the different types of social exchange behaviors that occur during meetings, using two studies to develop empirically distinct scales that reliably measure theoretically important types of exchange. Resource theory informed the initial measurement development efforts. Exploratory factor analyses from the first study led to revisions in the factor structure of the social exchange scales. The revised measure captured the exchange of emotional support, experiential information, humor, unwanted behaviors, and exchanges outside meetings. Confirmatory factor analyses from a follow-up study with a different sample of self-help support groups provided good model fit, suggesting the revised structure accurately represented the data. Further, the scales demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity with related constructs. Future research can use the scales to identify aspects of social exchange that are most important in improving health outcomes among self-help support group participants. Groups can use the scales in practice to celebrate strengths and address weaknesses in their social exchange dynamics.

Keywords: self-help, support groups, mutual support, social exchange, resource theory, measurement development

Self-help support groups are a popular strategy for addressing a variety of personal challenges, with approximately 18% of Americans using peer-led support groups in their lifetime (Kessler, Mickelson, & Zhao, 1997). Evaluation research suggests self-help support groups can be an effective resource for people facing addictions (Atkins & Hawdon, 2007; Kaskutas, 2009; Timko, Debenedetti, & Billow, 2006), severe mental health problems (Jones, Deville, Mayes, & Lobban, 2011; Pistrang, Barker, & Humphreys, 2008), and numerous medical conditions (Schulz et al., 2008; Sibthorpe, Fleming, & Gould, 1994). Within groups, the exchange of mutual support and experiential knowledge are widely believed to be central therapeutic processes (Brown, Shepherd, Merkle, Wituk, & Meissen, 2008; Humphreys, 2004). Although these social exchanges are critical in helping participants manage the challenge shared by group members, measures of these exchanges are underdeveloped (Brown & Lucksted, 2010). The only self-report measure of social exchange in support groups known to the authors captures support provided and received but does not distinguish between different types of support (Maton, 1988). The goal of the current study is to examine the empirical structure and psychometric properties of a multi-domain measure of social exchange in self-help support groups.

Some types of exchange are likely to be more beneficial than others. Thus, identifying the most valuable types of exchange is of substantial practical value because groups can take action to maximize the most beneficial exchanges. Further, the identification of harmful exchanges is equally important as groups can take action to prevent harmful exchanges. Before studies can identify beneficial and harmful exchanges, measures of distinct social exchange constructs must first be developed. Thus, the social exchange measure examined in this study can provide the research infrastructure necessary to identify the most beneficial and harmful exchanges that occur in self-help support groups.

Introduction to self-help support groups

Self-help support groups are a voluntary, self-determining, and non-profit gathering of people who share a condition or status; members share mutual support and experiential knowledge to improve persons’ experiences of the common situation (Society for Community Research and Action, 2013). These groups are distinct from self-help books or bibliotherapy, which are not addressed in the current study. Groups exist for thousands of different conditions but some of the most common address addictions, mental health, and parenting (White & Madera, 2002). Self-help support groups possess several strengths that help to explain their popularity. The donation driven nature of self-help support groups allows them to reach individuals who cannot afford professional services (Saha, Annear, & Pathak, 2013). Further, participation in groups can help reduce treatment costs and rates of rehospitalization (Humphreys & Moos, 2001; Landers & Zhou, 2011). Self-help support groups are effective across a wide range of racial, ethnic, and cultural groups and settings, both within the US and internationally (Chien, Thompson, & Norman, 2008; Humphreys & Woods, 1994). Part of their strength lies in their empowering nature, where participants help each other as equals rather than taking on dependency roles where they rely on the advice of professionals (Brown, 2009a). The act of helping others is known to be therapeutic, with help providers often benefitting more than help recipients according to the helper-therapy principle (Pagano, Post, & Johnson, 2011; Riessman, 1965). Thus, it is important to examine both what self-help participants give and receive in their social exchanges.

Social exchange in self-help support groups

Our examination of social exchange focuses specifically on behaviors. There are numerous important cognitions associated with exchange behaviors, such as the perceived rewards and costs described in social exchange theories (Stafford, 2008). However, these cognitions are conceptually distinct and require separate measurement from the frequency of behavioral exchange, which is the focus of this study.

To develop a theoretically grounded measure of social exchange, we drew from resource theory (Converse & Foa, 1993; Foa & Foa, 1974, 1980). Within resource theory, there are six types of resources that are exchanged: love, status, information, money, goods, and services. Of these six resource classes, love, status, and information can be regularly exchanged in the context of a self-help group meeting. An important benefit of self-help group participation is that members often become close friends and interact outside the context of meetings (Borkman, 1999). Interactions between friends can involve the exchange of all six resource classes described by resource theory. Thus, we developed a separate scale to capture the unique social exchanges that can occur between self-help group members outside of meetings. The following sections review each of these resources classes and their application to self-help groups in more detail.

Information

The exchange of information includes advice, opinions, instruction, and enlightenment, but not behaviors that can be defined as love or status (Foa & Foa, 1974, 1980). The exchange of information can lead to a variety of benefits including enhanced knowledge (Flühmann, Wassmer, & Schwendimann, 2012), relationship quality (Montgomery, 1981; Snyder, 1979), and team performance (Aubé, Brunelle, & Rousseau, 2013). In this study, we differentiate between two types of information: experiential knowledge and advice.

Experiential knowledge is the insight and information acquired through coping with life challenges (Brown & Lucksted, 2010). Learning from the experiences of others who face similar challenges can be powerful because the knowledge is typically concrete and pragmatic (Borkman, 1999). Perhaps most importantly, sharing personal experiences in an understanding environment with similar others enables validation, catharsis, and a reduction in social and emotional isolation (Coates & Winston, 1983; Finn, 1999; Helgeson & Gottlieb, 2000; Lieberman, 1993).

Although advice and instruction are types of information that can be exchanged in the context of self-help support groups, it is not clear whether such exchanges are beneficial or harmful. Many groups devote substantial time to learning coping techniques and problem solving strategies that can help in managing the challenge of interest (Adamsen & Rasmussen, 2003; Aglen, Hedlund, & Landstad, 2011). However, when members are sharing experiences, the provision of advice or instruction may leave the advice recipients feeling judged. Thus, many groups discourage the exchange of advice and instead provide instruction through readings or brief educational presentations. To ensure all measures of social exchange can be classified as either beneficial or harmful on theoretical grounds, we intentionally avoid measuring the exchange of advice or instruction.

Love

Foa and Foa (1980) define love as an expression of affectionate regard, warmth, or comfort. Exchanges of love have been found to enhance affectional bonds (Burr, 1973), emotional support (Ammons & Stinnett, 1980), and the development of friendship (Törnblom, Fredholm, & Jonsson, 1987). Self-help support groups are well suited for the exchange of love because people facing similar challenges are better able to understand, empathize with, and support one another (Brown & Wituk, 2010; Powell & Perron, 2010). Expressions of love are critical to the success of self-help groups because they encourage social bonding and unity (Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer, & Burlingame, 2010). The bonding, in turn, helps create a safe space for sharing without judgment. Thus, the exchange of love can facilitate the exchange of information in self-help support groups.

Status

The exchange of status consists of evaluative judgments that convey high or low prestige, regard, or esteem (Foa & Foa, 1974, 1980). Self-help groups operate as a medium for the exchange of status by providing participants opportunities to help others (Brown, 2009b). Members who share useful information during meetings receive positive status appraisals from individuals who find the information helpful (Brown, 2009b; Luks, 1991). Research suggests the provision of support and the receipt of positive status appraisals improves self-esteem and mental health (Brown, 2012; Maton, 1988).

Money, goods, and services

As previously discussed, money, goods, and services are not typically exchanged during self-help support group meetings. However, these resources can be exchanged in the context of close friendships that grow out of self-help group participation. Services such as help with transportation or various other favors are exchanged between friends. Money and goods can also be exchanged between friends, typically as gifts or loans. Such tangible exchanges can be conceptualized as the provision of instrumental social support, which helps people cope with a variety of everyday problems, enhance health, and reduce stress (Ostberg & Lennartsson, 2007; Schwarzer & Leppin, 1991).

Research Aims

This paper seeks to examine the empirical structure of social exchange in self-help support groups and describe the psychometric properties of measures for each domain of social exchange. Initially, we developed items to capture three domains of social exchange during self-help support group meetings – love, status, and information. The scales captured the frequency with which individuals provided and received these resources during meetings. We also developed a scale measuring the amount of social exchange with group members outside of meetings, with a focus on the exchange of money, goods, and services. We further developed and tested the instrument through two studies. The first study refined the instrument through quantitative and qualitative methods, using exploratory factor analysis to examine the structure of social exchange. The second study used a separate sample to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis examining the psychometric properties of the revised instrument. Findings inform discussion on applications for the measure, both in research and in practice settings.

Study 1 Method

Initial measurement development procedure

Our first measurement development step was to generate a large item pool that could capture the different domains of social exchange described by resource theory. We then shared our list of 87 items with 4 self-help group experts, who rated each item on its relevance and clarity (Netemeyer, Bearden, & Sharma, 2003). We removed items lacking high ratings on clarity or relevance and then pilot tested the survey with 5 self-help support group participants, interviewing them afterwards to obtain feedback about how to improve the survey, especially its clarity. After making revisions, we administered the survey to 278 self-help group members at two SHARE! self-help centers in Los Angeles, CA. The centers provide self-help support groups of all kinds with meeting space and technical assistance in starting and sustaining groups.

Sample

Survey respondents participated in 33 different types of self-help support groups, with the most common being Recovery International (10 groups), Co-Dependents Anonymous (14 groups), and Alcoholics Anonymous (13 groups). Other common groups included Cocaine Anonymous (6 groups), Debtors Anonymous (4 groups), and Narcotics Anonymous (3 groups). All groups were peer-led. Respondents were 42% Male and 58% Female, with an average age of 47 years old (SD = 14.01). With regard to race and ethnicity, 45% were White, 23% were Black, 13% were Hispanic, 10% were Asian, and 8% Other. The socioeconomic status of participants was modest, with a median family income between $10,000 and $20,000 and an average of 15 years of formal education (SD = 3.27 years). 50% of respondents were employed, working an average of 33 hours per week. 36% of respondents were parents, who had an average of 2 children.

Measures

A total of 74 survey items were organized into three separate scales: Social Exchanges Provided (30 items), Social Exchanges Received (27 items), and Exchanges Outside Meetings (17 items). The wording of items from Social Exchanges Provided and Social Exchanges Received typically mirrored one another. For example, the Social Exchanges Provided item, “I share my personal problems with group members” was mirrored by “Group members share their personal problems with me” in the Social Exchanges Received scale. All Social Exchanges Provided and Received items described behaviors indicative of the exchange of information, love, or status. Response options were Never, Rarely, Less than half the time, About half the time, More than half the time, Almost Always, and Always. Items from the Exchanges Outside Meetings scale also mirrored one another, capturing the giving and receiving of money, goods, services, and social visits. The Exchanges Outside Meetings scale used count response options of 0 times, 1 time, 2–3 times, 4–9 times, and 10 or more times in the last three months.

Missing data

The survey used a 3-form planned missing data design, which allowed for the collection of responses to 33% more questions than are answered by any one respondent (Graham, Taylor, Olchowski, & Cumsille, 2006). Form 1 (84 respondents) captured Exchanges Outside Meetings, among other scales. Form 2 contained Social Exchanges Provided and Social Exchanges Received (102 respondents) and Form 3 had all social exchange scales (92 respondents). Thus, although 278 individuals completed a survey, only 192 surveys contained the Social Exchanges Provided and Social Exchanges Received items. Of the 192 surveys, the amount of missing data ranged from 7%–10% for Social Exchanges Provided items and 11%–14% for Social Exchanges Received. The Exchanges Outside Meetings scale was in 176 surveys, with 13%–14% of item level data missing among respondents.

Study 1 Results

To refine the measures of social exchange, we first eliminated items that exhibited skewness or kurtosis values greater than 3. This criterion led to the elimination of several poorly distributed items that exhibited floor effects. Specifically, items describing unwanted behaviors performed by survey respondents during groups meetings were overwhelmingly rated as never or very rarely occurring. Yet, some unwanted behaviors performed by other group members were reported as occurring with substantially greater frequency. Thus, we kept items capturing unwanted behaviors received but not unwanted behaviors provided. Additionally, in the scale measuring social exchanges outside of meetings, respondents rarely reported providing or receiving money, goods, and specific services. The more general service of giving and receiving favors was more common, as was visiting and socializing with members outside of meetings.

With the reduced set of items, we conducted exploratory factor analyses (EFA) to identify empirically distinct aspects of social exchange. We used listwise deletion of missing data, running a separate EFA for each of the three scales – Social Exchanges Provided (n = 161), Social Exchanges Received (n = 149), and Exchanges Outside Meetings (n = 146). After determining the number of factors in each scale through scree plots and theoretical considerations, we eliminated items with high cross loadings (> .4) on other factors. Tables 1, 2, and 3 report factor loadings from the EFA of Social Exchanges Provided, Social Exchanges Received, and Exchanges Outside Meetings, respectively. Table 4 reports correlations between all factors identified through EFA, which were generally modest but significant.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis of social exchanges provided from Study 1.

| Item | Experiential Information Provided | Emotional Support Provided | Humor Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| I share my personal problems with group members. | .72 | .15 | .11 |

| I talk about personally sensitive issues. | .82 | .19 | .16 |

| I share my feelings with the group. | .72 | .30 | .29 |

| I express concern for a group member. | .11 | .70 | .27 |

| I provide emotional support to a group member. | .35 | .61 | .13 |

| I recognize the personal accomplishments of a group member. | .24 | .60 | .36 |

| I make jokes. | .37 | .21 | .45 |

| I laugh at the jokes of a group member. | .12 | .31 | .51 |

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis of social exchanges received from Study 1.

| Item | Emotional Support Received | Experiential Information Received | Humor Received | Unwanted Behaviors Received |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group members listen carefully when I talk. | .71 | .34 | .14 | −.20 |

| Group members show interest in hearing my ideas and opinions. | .64 | .29 | .33 | −.19 |

| Group members talk about sensitive issues. | .16 | .60 | .25 | .02 |

| Group members share their feelings with the group. | .34 | .65 | .03 | −.12 |

| Group members make jokes. | .08 | .12 | .51 | .25 |

| Group members laugh when I make a joke. | .17 | .11 | .62 | .05 |

| Group members stop listening to the discussion. | −.10 | −.14 | .21 | .57 |

| Other group members end up dominating the conversation. | −.13 | .02 | .03 | .61 |

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analysis of exchanges outside meetings from Study 1.

| Item | Exchanges Outside Meetings |

|---|---|

| I did a favor for a group member. | .81 |

| I visited the home of a group member. | .84 |

| I socialized with a group member outside of group meetings. | .82 |

| A group member did a favor for me. | .81 |

| A group member visited my home. | .85 |

Table 4.

Social exchange factor correlations with 95% confidence intervals from Study 1.

| Social Exchange Factor | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Emotional Support Provided | - | ||||||

| (2) Experiential Information Provided | .12 [−.03, .27] | - | |||||

| (3) Humor Provided | .43* [.29, .54] | .21* [.05, .35] | - | ||||

| (4) Emotional Support Received | .20* [.03, .35] | .21* [.04, .36] | .14 [−.03, .30] | - | |||

| (5) Experiential Information Received | .28* [.12, .43] | .42* [.27, .55] | .17* [.002, .33] | .35* [.20, .48] | - | ||

| (6) Humor Received | .29* [.13, .44] | .16 [.004, .32] | .56* [.43, .66] | .26* [.10, .40] | .14 [−.02, .29] | - | |

| (7) Unwanted Behaviors Received | −.06 [−.23, .10] | −.10 [−.26, .07] | .09 [−.08, .25] | −.26* [−.41, .−11] | −.06 [−.22, .10] | .22* [.07, .37] | - |

| (8) Exchanges Outside Meetings | .25* [.002, .46] | −.03 [−.27, .21] | .13 [−.12, .36] | −.13 [−.36, .12] | −.01 [−.25, .24] | .25* [.003, .47] | .13 [−.12, .36] |

p < .05

EFA results were similar for both Social Exchanges Provided and Received. Information exchange items loaded on a single factor, which we named Experiential Information to enhance its descriptive specificity. Items about joking around with others also loaded on a single distinct factor, which we named Humor. Several items representing Love and Status often cross loaded on multiple factors. However, a small number of items representing expressions of both love and status loaded on a single unique factor, which we subsequently named Emotional Support.

Only the Social Exchanges Received scale contained items describing problematic behaviors such as not listening to the discussion or dominating the conversation. These items loaded on a single distinct factor irrespective of the item’s initial grouping into the information, love, or status category. We labeled this factor Unwanted Behaviors Received. Results from the EFA of the Exchanges Outside Meetings scale indicated the items were best represented as a single factor measuring the quantity of social exchange with group members outside of meetings.

To identify aspects of social exchange we had not yet tried to measure quantitatively, we examined responses to two open-ended survey questions. The first question sought to identify helpful social exchanges by asking, “What would you like to see group members do more of during meetings?” Responses to this question were already described by existing items. To identify unwanted social exchanges, the second question asked, “What would you like to see group members do less of during meetings?” Several responses were not captured by existing items and were thus added to the Unwanted Behaviors Received scale. We also revised the wording of existing items to create a more consistent format for the Unwanted Behaviors Received scale.

Study 2 Method

We conducted a follow-up study with 194 parents from 18 parenting self-help support groups in El Paso, TX and Las Cruces, NM. All groups were parent-led. We administered a web-based survey via email (45 respondents) and passed out paper surveys during meetings (149 respondents). An important strength of our survey was that it presented social exchange items in a random order on each survey, to eliminate the statistical effect of biases caused by the order of items (Friedman & Amoo, 1999).

Of the 194 participants, 143 were from five Mothers of Preschoolers (MOPS) groups, which are Christian groups for parents of children ages 0 to 5. Other groups participating served parents of children with special needs such as autism, special interests such as attachment parenting, or operated as playgroups with less meeting structure. Respondents were predominantly female (99%), with an average age of 34 years old (SD = 6.5). With regard to race and ethnicity, 54% were White, Non-Hispanic, 38% were Hispanic, 2% were Black, Non-Hispanic, 2% were Asian, and 2% were other. The socioeconomic status of participants was generally high, with a median educational attainment of technical training beyond high school or some college and a median family income between $50,000 and $75,000. Most participants were married (93%) and not employed (79%), with a median of 2 children.

Measures

Table 5 reports the number of items, definitions, and sample items of each social exchange scale used in the follow-up study. To improve scale reliabilities, we added an item to scales from the first study with only two items. The appendix provides the items that make up the revised scales. We measured several related constructs to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of the social exchange scales. The constructs examined are Participation Benefits, Participation Difficulties, Group Cohesion, and Group Conflict. Participation Benefits (27 items; α = .98) measures the degree to which respondents perceive to have experienced several potential benefits of group involvement (e.g. “This group helps me stay focused on my goals”). Participation Difficulties (21 items; α = .85) asks respondents to rate the extent to which they have experienced various difficulties related to their group involvement (e.g. “The meeting demands too much time”). Group Cohesion (8 items; α = .85) measures the extent to which a sense of unity, belonging, and friendship exists among group members. Group Conflict (6 items; α = .77) assesses the amount of arguing and hostility between group members (e.g. “Some members are quite hostile to other members”). Group Cohesion and Group Conflict are modified versions of subscales from the Group Environment Scale for Cohesion, and Anger and Aggression, respectively (Moos, 2002).

Table 5.

Social exchange scale internal reliabilities, definitions, and example items.

| Social exchange scale | Num items | Alpha | Definition | Example item |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Support Provided | 3 | .63 | Supporting the emotional needs of group members by expressing concern and providing encouragement | I express concern for a group member. |

| Experiential Information Provided | 3 | .83 | Sharing personal experiences, problems, and feelings with group members. | I share my personal problems with group members. |

| Emotional Support Received | 3 | .77 | Being heard and encouraged by fellow group members. | Group members listen carefully when I talk. |

| Experiential Information Received | 3 | .77 | Learning about the personal experiences, problems, and feelings of fellow group members. | Group members share their personal problems with me. |

| Unwanted Behaviors Received | 7 | .81 | Problematic behaviors that interfere with group dynamics such as interruptions, gossip, and criticism. | A group member is not quiet when I am talking. |

| Humor Exchanged | 5 | .84 | Making jokes and laughing with group members. | I kid around with group members. |

| Exchanges Outside Meetings | 5 | .88 | Socializing and exchanging favors with group members outside of meetings. | In the last 3 months, about how many times did you do a favor for a group member? |

p < .05

Plan of analysis

We examined the revised factor structure of the Social Exchanges Given, Social Exchanges Received, and Exchanges Outside Meetings in a single Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) measurement model using Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). We estimated the model via the method of full information maximum likelihood, which has the advantage of being able to estimate missing data (e.g., Wothke, 2000). Missing data was however minimal, with between 0 and 2% missing across items.

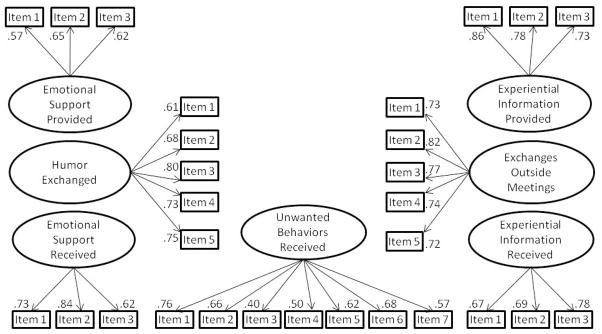

Study 2 Results

Table 5 reports the internal consistency of the social exchange scales using Cronbach’s alpha values, which ranged from .63 to .88. Figure 1 presents the standardized parameter estimates and fit indices for the CFA of the social exchange scale measurement model. The initial CFA had χ2 of 594.84 (df = 377, p < .05), a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of .91, and an RMSEA of .06. Due to a correlation of .85 between Humor Provided and Received, we subsequently modeled Humor as a single factor, dropping one Humor item that cross-loaded on Emotional Support Provided. The revised model was more parsimonious and had slightly better fit with a χ2 of 566.24 (df = 356, p < .05), a CFI of .91 and a RMSEA of .06.

Figure 1.

Social exchange scale measurement model with standardized path coefficients.

Note: Correlations between latent variables not shown. χ2 = 530.97 (df = 354, p< .05); CFI = .92; RMSEA = .05;

Modification indices identified strong correlations between two items pairs that mirrored one another. When we modeled these two correlations, the CFI improved to .92 and the RMSEA to .05. The first pair was about sharing personally sensitive issues, with one item coming from Experiential Information Provided and another from Experiential Information Received (r = .39, p < .01). A second pair of items from the Exchanges Outside Meetings scale focused on the giving and receiving of favors (r = .35, p < .01). Standardized factor loadings ranged from .57 to .86 for all scales except for Unwanted Social Exchanges, where factor loadings ranged from .40 to .76.

Table 6 reports the correlations between the social exchange scales. For scales measuring social exchanges during meetings, correlations generally ranged from .34 to .53. However, correlations between Unwanted Social Exchanges and other scales were generally low and non-significant, except in the case of Emotional Support Received, where the correlation was −.27 (p < .01). Exchanges Outside Meetings also had relatively small and non-significant correlations with other scales, but was significantly correlated with Humor Exchanged (r = .20, p < .01).

Table 6.

Correlations with 95% confidence intervals between the social exchange scales and indicators of convergent and discriminant validity from Study 2.

| Social exchange scale |

(1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | Part. Benefits |

Part. Difficulties |

Group Cohesion |

Group Conflict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Emotional Support Provided | - | .37* [.24, .49] | −.22* [−.36, −.09] | .32* [.19, .44] | −.15* [−.28, −.01] | |||||

| (2) Experiential Information Provided | .47* [.35, .57] | - | .36* [.23, .48] | −.30* [−.43, −.17] | .24* [.11, .37] | −.10 [−.24, .04] | ||||

| (3) Emotional Support Received | .48* [.37, .58] | .37* [.24, .48] | - | .53* [.42, .62] | −.38* [−.50, −.25] | .47* [.35, .57] | −.32* [−.42, −.19] | |||

| (4) Experiential Information Received | .52* [.41, .61] | .53* [.41, .62] | .49* [.37, .59] | - | .46* [.34, .57] | −.20* [−.33, −.06] | .44* [.32, .54] | −.15* [−.28, −.01] | ||

| (5) Unwanted Behaviors Received | −.17 [−.30, −.02] | −.09 [−.22, .05] | −.27* [−.40, −.14] | −.003 [−.14, .14] | - | −.22* [−.35, −.08] | .39* [.27, .51] | −.34* [−.46, −.21] | .42* [.30, .53] | |

| (6) Humor Exchanged | .34* [.21, .46] | .47* [.35, .57] | .44* [.31, .55] | .48* [.37, .58] | .01 [−.13, .15] | - | .29* [.15, .41] | −.17* [−.30, −.03] | .27* [.13, .39] | −.14 [−.27, .001] |

| (7) Exchanges Outside Meetings | .09 [−.05, .23] | .11 [−.03, .25] | .06 [−.08, .20] | .06 [−.08, .20] | .07 [−.07, .21] | .20* [.06, 33] | .23* [.09, .36] | −.07 [−.20, .08] | .07 [−.07, .21] | .11 [−.04, .24] |

Note:

p < .01;

Part. = Participation;

To examine convergent and discriminant validity, Table 6 also reports correlations between the social exchange scales and four related constructs – Participation Benefits, Participation Difficulties, Group Cohesion, and Group Conflict. Results indicate the social exchange scales are consistently correlated as expected with Participation Benefits, Participation Difficulties, and Group Cohesion. The one exception was a non-significant positive correlation between Cohesion and Exchanges Outside Meetings. Correlations with Group Conflict were less consistent. Emotional Support Received and Experiential Information Received both possessed a significant negative correlation with Group Conflict, whereas Unwanted Behaviors Received was positively correlated.

The social exchange scales possessing the largest correlations with Participation Benefits were Emotional Support Received (r = .53) and Experiential Information Received (r = .46). Similarly, Emotional Support Received and Experiential Information Received had the largest correlations with Group Cohesion (r = .47 and .44, respectively). Unwanted Behavior Received had the largest correlation with Participation Difficulties and Group Conflict (r = .39 and .42, respectively).

Discussion

Results from studies 1 and 2 provide insight into the structure of social exchange in self-help support groups. Exploratory factor analyses suggested our initial classification of items into love, status, and information as suggested by Resource Theory was not consistent with the data. Instead, items describing love and status were merged into a single factor called emotional support, which is commonly identified as a type of social support in the literature (House & Kahn, 1985; Taylor, 2011). Humor unexpectedly emerged as a distinct and commonly occurring type of social exchange. Although jokes and kidding are often exchanged in mutually supportive settings, it is less clear how humorous exchanges impact health. Humor may help participants regulate affect and facilitate bonding between members (Brown, 2009b; Nicholas, McNeill, Montgomery, Stapleford, & McClure, 2003). Information exchange was empirically distinct, as anticipated, but was renamed Experiential Information to provide a more specific description of the items included. Unwanted social exchanges emerged as an independent factor, perhaps not surprisingly given that negatively worded items tend to load highly on factors that are distinct from positively worded items (Netemeyer, et al., 2003).

Interestingly, participants reported unwanted behaviors by other group members but not by themselves. Participants may not notice their unwanted behaviors because groups avoid overtly pointing them out and instead focus on modeling desired behaviors. Group members may learn to stop unwanted behaviors over time both through the modeling of appropriate behaviors and because they decide to avoid the unwanted behaviors they notice in others (Riva & Korinek, 2004). Another potential explanation for the low rates of self-reported unwanted behaviors is a social desirability bias (Krumpal, 2013).

Confirmatory factor analyses generally had good model fit, suggesting the revised factor structure accurately represents social exchange in self-help groups. All items maintained relatively high factor loadings on their intended latent variable without high cross-loadings on other latent variables, thus preserving a simple structure with empirically distinct constructs. This is an important strength of the measure for future research examining how social exchange influences self-help support group outcomes. Each scale may predict unique portions of variance in outcomes of interest or manifest distinct relations with different sets of outcomes. An additional strength of the scales is their internal consistency, which generally ranged from good to excellent (Kline, 1999). However, Cronbach’s alpha on the scale measuring emotional support was only .63, which is considered acceptable but could be improved with additional items.

Model fit, as measured by CFI but not RMSEA, could be improved modestly (from .91 to .93) by modeling correlations between error terms on two types of exchange that mirrored one another. This finding reflects the idea that giving a specific type of resource often leads to reciprocity with a similar resource, such as favors for favors (Foa & Foa, 1980). Similarly, providing humor could not be empirically distinguished from receiving humor, suggesting that self-help group members regularly respond to jokes with more jokes.

Analyses examining the associations between the social exchange scales and related constructs supported their convergent and discriminant validity. All scales were associated with participation benefits, difficulties, group cohesion, and conflict in the expected direction. Not surprisingly, social exchanges outside meetings had relatively small and often non-significant relations with the group focused characteristics used for convergent and discriminant validity analyses. The development of social exchanges outside meetings may nevertheless contribute to health outcomes among socially isolated individuals (Thoits, 2010).

The social exchange scales have applications for both research and practice. Future studies can use the scales to examine the consequences of different social exchanges in self-help support groups. If one type of social exchange emerges as particularly important in attaining an outcome of interest, groups can focus on maximizing that type of social exchange. Furthermore, research may be able to identify group and individual characteristics that enhance beneficial social exchanges and minimize harmful exchanges. Groups can then target relevant group and individual characteristics in their efforts to enhance beneficial social exchanges and minimize harmful exchanges.

Another practical application of the social exchange scales is in their use as part of a group functioning feedback system. Currently we create feedback reports based on survey responses that groups can use to celebrate strengths and address weaknesses. To be successful, such a feedback process requires first establishing a trusting relationship with a group and then working with members to develop strategies that can address weaknesses.

Limitations and future directions

Although the first study sampled a variety of self-help groups, the psychometric properties reported in Study 2 are based only on parenting self-help groups and may vary across types of groups. Participants in the parent groups were predominantly female, married, and of Non-Hispanic White or Hispanic decent. Further, we only sampled current participants and not dropouts, whose response patterns may follow a different structure. Future research with dropouts, a larger variety of groups, and a broader range of participant demographics are needed to explore the generalizability of the current factor structure.

The validity analyses have important limitations to consider. First, the measures used to examine concurrent and discriminant validity do not have previously established psychometric properties. However, Cronbach’s alpha values from this study indicate the measures have good internal consistency. Further, the group cohesion and conflict measures draw from the well established group environment scales (Moos, 2002). Another validity analysis concern is that the correlations may be inflated. All measures rely on respondent perceptions and are subject to social desirability bias, which could skew responses in the same direction. Context effects from answering one scale may also influence responses to subsequent scales, thereby increasing correlations. Conceptual similarities between social exchange scales such as receiving emotional support and validity measures such as participation benefits could also inflate correlations. However, it is important to note that the social exchanges scales are conceptually unique in their focus on the frequency of specific behaviors rather than cognitions.

The predictive validity of the scales remains unknown. Future research can examine whether the identified social exchanges are in fact predictive of health outcomes such as improved social support, reduced stress, and enhanced coping skills. The use of observational measures of social exchange and the examination of their association with the self-report scales could help to further establish the validity of the scales described here. Additionally, future research to establish test-retest reliability across multiple meetings is needed to explore whether the social exchange scales are capturing enduring group characteristics that can be subsequently modified. The utility of the social exchange scales may be limited if responses fluctuate substantially in reaction to the most recent meeting.

A theoretical limitation of our measurement development efforts is the absence of items that capture social comparisons. Upward, downward, and lateral social comparisons are often described as important therapeutic processes in self-help groups (Brown & Lucksted, 2010; Lucksted, Stewart, & Forbes, 2008). Future research needs to examine whether information exchanges that enable upward, downward and lateral comparisons are distinct from the information exchanges currently captured by the instrument.

Conclusion

As a description of behaviors that influence the therapeutic quality of support groups, social exchanges are at the heart of self-help group processes. To understand how social exchanges lead to participation benefits is central to effectively describing how people benefit from self-help support groups. Some social exchanges measured here may be important in contexts outside of self-help groups, especially other types of therapeutic groups. Over time, it may be possible to develop a catalog of social exchange scales that influence well-being in numerous contexts. A particular setting could then use social exchange scales that are relevant to their context. This study represents an important step in understanding how social exchanges and self-help support groups can influence health. The social exchange scales presented here are ready to move forward research and practice with self-help support groups.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20MD002287. Additionally, this article is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute through a Community Networks Program Center grant U54 CA153505. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge the valuable feedback provided by Thomasina Borkman, Alicia Lucksted, and Deborah Salem in developing the measure described in this paper. We are also grateful for the many self-help support group members who participated in this research.

Appendix. Self-Help Support Group Social Exchange Scales

Social exchange during meetings

The following questions ask about what goes on during group meetings. Please indicate how often each behavior occurs during your group’s meetings.

| During group meetings… | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Very rarely | Less than half the time | About half the time | More than half the time | Almost always | Always | |

| Experiential Knowledge Provided: | |||||||

| I share my personal problems with group members. | |||||||

| I talk about personally sensitive issues. | |||||||

| I share my feelings with the group. | |||||||

| Emotional Support Provided: | |||||||

| I express concern for a group member. | |||||||

| I provide emotional support to a group member. | |||||||

| I recognize the personal accomplishments of a group member. | |||||||

| Experiential Knowledge Received: | |||||||

| Group members share their personal problems with me. | |||||||

| Group members talk about sensitive issues. | |||||||

| Group members share their feelings with the group. | |||||||

| Emotional Support Received: | |||||||

| Group members listen carefully when I talk. | |||||||

| Group members show interest in hearing my ideas and opinions. | |||||||

| A group member expresses confidence in my abilities. | |||||||

| Humor Exchanged: | |||||||

| Group members make jokes. | |||||||

| Group members laugh when I make a joke. | |||||||

| Group members kid around with me. | |||||||

| I make jokes. | |||||||

| I kid around with group members. | |||||||

| Unwanted Behavior Received: | |||||||

| A group member is not quiet when I am talking. | |||||||

| A group member interrupts me while I am talking. | |||||||

| A group member shows up late to the meeting. | |||||||

| There is a misunderstanding between group members. | |||||||

| A group member gossips. | |||||||

| A group member stops listening to the discussion. | |||||||

| A group member ends up talking for too long. | |||||||

Exchanges outside meetings

This section asks about what you and other group members may have done together. Please indicate about how many times you did each activity listed. Don’t worry if you answer 0 times often, as many people do.

| In the last 3 months, about how many times did… | 0 times | 1 time | 2–3 times | 4–9 times | 10 or more times |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| you do a favor for a group member. | |||||

| you visit the home of a group member. | |||||

| you socialize with a group member outside of group meetings. | |||||

| a group member do a favor for you. | |||||

| a group member visit your home. |

References

- Adamsen L, Rasmussen JM. Exploring and encouraging through social interaction: A qualitative study of nurses’ participation in self-help groups for cancer patients. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26:28–36. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aglen B, Hedlund M, Landstad BJ. Self-help and self-help groups for people with long-lasting health problems or mental health difficulties in a Nordic context: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2011;39(8):813–822. doi: 10.1177/1403494811425603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammons P, Stinnett N. The vital marriage: A closer look. Family Relations. 1980;29:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins RG, Hawdon JE. Religiosity and participation in mutual-aid support groups for addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubé C, Brunelle E, Rousseau V. Flow experience and team performance: The role of team goal commitment and information exchange. Motivation and Emotion. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11031-013-9365-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkman TJ. Understanding self-help/mutual aid: Experiential learning in the commons. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD. How people can benefit from mental health consumer-run organizations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009a;43:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD. Making it sane: Using life history narratives to explore theory in a mental health consumer-run organization. Qualitative Health Research. 2009b;19:243–257. doi: 10.1177/1049732308328161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD. Consumer-run mental health: Framework for recovery. New York: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Lucksted A. Theoretical foundations of mental health self-help. In: Brown LD, Wituk SA, editors. Mental health self-help: Consumer and family initiatives. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Shepherd MD, Merkle EC, Wituk SA, Meissen G. Understanding how participation in a consumer-run organization relates to recovery. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Wituk SA. Introduction to mental health self-help. In: Brown LD, Wituk S, editors. Mental health self-help: Consumer and family initiatives. New York, NY US: Springer Science + Business Media; 2010. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Burr WR. Theory construction and the sociology of the family. New York: Wiley; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CL, Baker EL, Porter G, Thayer SD, Burlingame GM. Rating group therapist interventions: The validation of the Group Psychotherapy Intervention Rating Scale. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2010;14(1):15–31. doi: 10.1037/a0016628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chien WT, Thompson DR, Norman I. Evaluation of a peer-led mutual support group for Chinese families of people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42:122–134. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates D, Winston T. Counteracting the deviance of depression: Peer support groups for victims. Journal of Social Issues. 1983;39:169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Converse J, Jr, Foa UG. Some principles of equity in interpersonal exchanges. In: Foa UG, Converse J Jr, Törnblom KY, Foa EB, editors. Resource theory: Explorations and applications. San Diego, CA US: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Finn J. An exploration of helping processes in an online self-help group focusing on issues of disability. Health & Social Work. 1999;24(3):220–231. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flühmann P, Wassmer M, Schwendimann R. Structured information exchange on infectious diseases for prisoners. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2012;18(3):198–209. doi: 10.1177/1078345812445180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa UG, Foa EB. Societal structures of the mind. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Foa UG, Foa EB. Resource theory: Interpersonal behavior as exchange. In: Gergen KJ, Greenberg MS, Willis RH, editors. Social exchange: Advances in theory and research. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HH, Amoo T. Rating the rating scales. Journal of Marketing Management. 1999;9:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Olchowski AE, Cumsille PE. Planned missing data designs in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 2006;11(4):323–343. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.11.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Gottlieb BH. Support groups. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Kahn RL. Measures and concepts of social support. In: Cohen S, Syme SL, editors. Social support and health. New York: Academic; 1985. pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Circles of recovery: Self-help organizations for addictions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Moos R. Can encouraging substance abuse patients to participate in self-help groups reduce demand for health care? A quasi-experimental study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:711–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Woods MD. Researching mutual-help group participation in a segregated society. In: Powell TJ, editor. Understanding the self-help organization: Frameworks and findings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Deville M, Mayes D, Lobban F. Self-management in bipolar disorder: The story so far. Journal of Mental Health. 2011;20:583–592. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2011.600786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA. Alcoholics Anonymous effectiveness: Faith meets science. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2009;28:145–157. doi: 10.1080/10550880902772464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Zhao S. Patterns and correlates of self-help group membership in the United States. Social Policy. 1997;27:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kline P. The handbook of psychological testing. 2. London: Routledge; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology. 2013;47(4):2025–2047. doi: 10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landers GM, Zhou M. An analysis of relationships among peer support, psychiatric hospitalization, and crisis stabilization. Community Mental Health Journal. 2011;47(1):106–112. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA. Self-help groups. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, editors. Comprehensive group therapy. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, Stewart B, Forbes C. Benefits and changes for family to family graduates. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42:154–166. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luks A. The helping power of doing good: The health and spiritual benefits of helping others. New York: Fawcett Columbine; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI. Social support, organizational characteristics, psychological well-being, and group appraisal in three self-help group populations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1988;16:53–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00906072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BM. The form and function of quality communication in marriage. Family Relations. 1981;30:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Group environment scale manual: Development, applications, research. 3. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Version 6.0. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer RG, Bearden WO, Sharma S. Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas DB, McNeill T, Montgomery G, Stapleford C, McClure M. Communication Features in an Online Group for Fathers of Children with Spina Bifida: Considerations for Group Development Among Men. Social Work with Groups: A Journal of Community and Clinical Practice. 2003;26(2):65–80. doi: 10.1300/J009v26n02_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg V, Lennartsson C. Getting by with a little help: The importance of various types of social support for health problems. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007;35:197–204. doi: 10.1080/14034940600813032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Post SG, Johnson SM. Alcoholics Anonymous-related helping and the helper therapy principle. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2011;29(1):23–34. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2011.538320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang N, Barker C, Humphreys K. Mutual help groups for mental health problems: A review of effectiveness studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42(1–2):110–121. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell TJ, Perron BE. The contribution of self-help groups to the mental health/substance use services system. In: Brown LD, Wituk S, editors. Mental health self-help: Consumer and family initiatives. New York, NY US: Springer Science + Business Media; 2010. pp. 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman F. The “helper” therapy principle. Social Work. 1965;10:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Riva MT, Korinek L. Teaching Group Work: Modeling Group Leader and Member Behaviors in the Classroom to Demonstrate Group Theory. Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2004;29(1):55–63. doi: 10.1080/01933920490275402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Annear PL, Pathak S. The effect of Self-Help Groups on access to maternal health services: evidence from rural India. [Article] International Journal for Equity in Health. 2013;12(1):36–44. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz U, Pischke CR, Weidner G, Daubenmier J, Elliot-Eller M, Scherwitz L, DO Social support group attendance is related to blood pressure, health behaviours, and quality of life in the multicenter lifestyle demonstration project. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2008;13:423–437. doi: 10.1080/13548500701660442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Leppin A. Social support and health: A theoretical and empirical overview. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sibthorpe B, Fleming D, Gould J. Self-help groups: A key to HIV risk reduction for high-risk injection drug users? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1994;7:592–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DK. Multidimensional assessment of marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:813–823. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Community Research and Action. Resolution on self-help support groups. Palm Beach Gardens, FL: Society for Community Research and Action; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford L. Social exchange theories. In: Baxter LA, Braithewaite DO, editors. Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. pp. 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Social support: A review. In: Friedman MS, editor. The handbook of health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(1, Suppl):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Debenedetti A, Billow R. Intensive referral to 12-Step self-help groups and 6-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnblom KY, Fredholm EM, Jonsson DR. New and old friendships: Attributed effects of type and similarity of transacted resources. Human Relations. 1987;40:337–359. doi: 10.1177/001872678704000602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White BJ, Madera EJ. The self-help group sourcebook: Your guide to community and online support groups. 7. Denville, NJ: Saint Clares Health Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. Longitudinal and multi-group modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]