Abstract

Context:

Junior doctors are reported to make most of the prescribing errors in the hospital setting.

Aims:

The aim of the following study is to determine the knowledge intern doctors have about prescribing errors and circumstances contributing to making them.

Settings and Design:

A structured questionnaire was distributed to intern doctors in National Hospital Abuja Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods:

Respondents gave information about their experience with prescribing medicines, the extent to which they agreed with the definition of a clinically meaningful prescribing error and events that constituted such. Their experience with prescribing certain categories of medicines was also sought.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data was analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 17 (SPSS Inc Chicago, Ill, USA). Chi-squared analysis contrasted differences in proportions; P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results:

The response rate was 90.9% and 27 (90%) had <1 year of prescribing experience. 17 (56.7%) respondents totally agreed with the definition of a clinically meaningful prescribing error. Most common reasons for prescribing mistakes were a failure to check prescriptions with a reference source (14, 25.5%) and failure to check for adverse drug interactions (14, 25.5%). Omitting some essential information such as duration of therapy (13, 20%), patient age (14, 21.5%) and dosage errors (14, 21.5%) were the most common types of prescribing errors made. Respondents considered workload (23, 76.7%), multitasking (19, 63.3%), rushing (18, 60.0%) and tiredness/stress (16, 53.3%) as important factors contributing to prescribing errors. Interns were least confident prescribing antibiotics (12, 25.5%), opioid analgesics (12, 25.5%) cytotoxics (10, 21.3%) and antipsychotics (9, 19.1%) unsupervised.

Conclusions:

Respondents seemed to have a low awareness of making prescribing errors. Principles of rational prescribing and events that constitute prescribing errors should be taught in the practice setting.

Keywords: Hospital setting, internship training, junior doctors, prescribing errors

Introduction

The essence of good prescription writing is to ensure that the pharmacist knows exactly, which drug formulation and dosage to dispense and the patient has clear written instruction for self-administration of the prescribed drug.[1] A prescription is a legal document that carries regulations to ensure safe use and to comply with governmental regulations.

Aronson[2] has noted that the writing of a prescription is preceded by four steps in the prescribing process viz. making an accurate diagnosis; assessing the balance of benefit to harm; selecting the right drug among a range of alternatives and the right dosing regimen and discussion with the patient about the proposed treatment, potential beneficial and adverse effects. World-wide, prescribing errors in clinical practice are common.[3,4,5,6] These errors can affect the safety of patients either hospitalized or ambulatory. Studies have shown that in about half of hospital admissions, physicians may make one prescribing error or the other.[7] Errors are more likely to occur with junior doctors[7,8,9] but are still prevalent in other senior categories of doctors.[7,10] Errors in prescribing can be attributed to a variety of factors including individual, environmental and organizational such as lack of knowledge, insufficient training, workload and communication.[7,9,11,12] They are difficult to quantify due to problems with available data, error definition and study design.[13] Using the Delphi technique, Dean et al.[14] developed a general definition of a clinically meaningful prescribing error which has been widely adopted in literature to measure baseline incidence of prescribing errors in the UK and elsewhere.

Some researchers[15] have reported that foundation (intern) year doctors lack confidence in prescribing several groups of medicines with the majority of them feeling that undergraduate education in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics had not prepared them adequately for prescribing duties.

The broad aims of medical school training are to lay the foundation for a medical career and to provide junior doctors with appropriate knowledge and skills for the first stage of their post-qualification career.[16] Although diversity of curriculum approaches in medical schools is encouraged, the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria is responsible for the design and regulation of undergraduate medical education in Nigeria.[17] Medical training in Nigeria spans a minimum of 6 years but it is in the 4th year onward that clinical training begins. This is the period where undergraduate pharmacology courses including topics in basic and clinical pharmacology as well as therapeutics are taught.

Conventionally, all newly graduated doctors are required to undergo internship in accredited hospitals for a year before full registration to practice. Internship is a period of medical apprenticeship under the supervision of a consultant. The intern is expected to learn clinical skills, perform some clinical procedures and demonstrate good clinical judgment to arrive at patient management decisions. Interns are consequently the most junior doctors in a tertiary hospital. The first experience of unsupervised prescribing begins during the internship year. Junior doctors are the most frequent prescribers in the hospital setting and are reported to make most of the prescribing errors.[7,8,18] Knowing what drug to prescribe to which patient does not necessarily translate to a good prescription. Considering the fact that the majority of prescription-related errors in the hospital environment are made by junior doctors, it is necessary to educate the interns and develop interventions that will improve the prescribing qualities.

Previous studies carried out in the Nigeria hospital setting reported that prescribing errors were common though may not always result in actual adverse outcomes for patients.[19,20] In the few studies examining the quality of prescribing by Nigerian medical practitioners, there appears to be a need to improve prescribing quality. However, it is not easy to change the prescribing habits of experienced doctors, thus there is the hope that educating junior doctors to prescribe according to a standard guideline may be a more effective intervention. This study was therefore aimed to determine the knowledge junior doctors have about prescribing errors, their perception of events that constitute a prescribing error, factors that contribute to prescribing errors, medicines less confidently prescribed and circumstances in which they were prone to making prescribing errors.

Subjects and Methods

This study was carried out in National Hospital Abuja (NHA) located in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria. Nigeria is made up of 36 states and the FCT, an area situated in the geographic center of Nigeria. Being a Federal Government-Funded Hospital, NHA is accredited for medical internship training. Accredited hospitals for an internship in Nigeria include all the teaching hospitals affiliated to medical schools, military hospitals, some general (secondary care) hospitals and a few private hospitals. NHA along with the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH) are the only two tertiary hospitals situated in the FCT. Tertiary hospitals, apart from providing referral services to the numerous primary and secondary health care facilities within their territories and beyond, also serve as institutions for training of health personnel offering undergraduate, graduate, post-graduate and residency programs. Currently, a 200-bed tertiary hospital, NHA plays a key role in the provision of health services to the residents of Abuja, a cosmopolitan multi-ethnic, multi-cultural urban city with high socio-economic disparity.

A structured questionnaire modified from the work of Dean et al.[14] was the instrument of study. It was constructed based on the definition of and events that represented prescribing errors obtained from a consensus agreement of a wide range of health care professionals [Appendix]. The questionnaire sought information from the junior doctors about their demographics, undergraduate training, qualification, present posting, whether they agreed with the definition of prescribing error and the events that represented such, their experience and confidence with prescribing certain drug categories and circumstances under which they were likely to make a prescribing error. Prescribing errors are common among prescribers in Nigeria.[18,19,20] This problem coupled with a low self-awareness of making prescribing errors, prompted our inclusion of interns perception of prescribing errors in the parameters assessed. The questionnaire included a 5-point Likert scale ranging from totally agree to totally disagree to determine respondents’ level of agreement with events that constitute a prescribing error [Appendix]. Most of the questions required selecting from a multiple of suggested options. The questionnaire was initially piloted at the UATH, FCT and was excluded from the study.

A total of 33 copies of the questionnaire were randomly distributed to house officers (HO) who were undergoing internship at the hospital during November 2011 and January 2012. These junior doctors are admitted in two batches of 6 months spread and undergo 3 months clerkship/rotation in the four major clinical specialties: Medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics and Obstetrics and Gynecology Departments. HO who were willing to voluntarily participate in the study were given the questionnaires to fill individually. Confidentiality of information tendered was assured to the participants. The ethics committee of the hospital approved the study.

Each questionnaire used in this study was coded for easy reference. The data obtained was analyzed with SPSS version 17 in terms of demographic characteristics, qualification, current and previous posting and prescribing experience using frequencies and percentages as appropriate. Chi-square test was adopted in estimating possible differences in proportions. At a confidence interval of 95%, a 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Demographics

Of the 33 questionnaires distributed to the junior doctors, 30 were duly filled and returned giving a response rate of 90.9%. The respondents were predominantly males (19, 63.3%) thus a statistical gender balance was not achieved (χ2= 0.54, P = 0.524). A majority of the respondents (23, 76.7%) were between 25 and 35 years. Only 7 (13.3%) were below 25 years. All but one graduated from a Nigeria medical school and all respondents had the bachelor of medicine and bachelor of Surgery degree only. 18 (60%) respondents had rotated through two major clinical postings (medicine, pediatrics), 4 (13.3%) through surgery, medicine. obstetrics and gynecology and 3 (10%) through the four major postings. 5 (16.7%) respondents were presently in their first posting in the medicine department.

Prescribing experience

Twenty seven (90%) of the respondents had <1 year of prescribing experience. When asked of the frequency at which they prescribed medicines at the hospital, 22 (73%) claimed to prescribe medicines “every day or more,” another 7 (23.3%) prescribed medicines 2-6 times a week while only 1 (3.3%) admitted to prescribing once a week.

Knowledge and self-awareness of prescribing errors

Eleven (36.7%) respondents each admitted to “rarely” (<5% of time) and “seldom” (5-10% of time) made prescription errors respectively. Six (20%) agreed to making prescribing errors sometimes (10-20% of time) while two (6.7%) denied ever making a prescribing error (0%). When asked the frequency at which a fellow clinician (doctor, pharmacist or nurse) had called the attention of the respondent to a prescription written by the respondent and that resulted to an alteration of such, 13 (43.3%) respondent claimed they had “rarely” (<5% of time) been called to such while 9 (30%) assented to have “seldom” (5-10% of time) been alerted this way, 3 (10%) asserted to “sometimes” (10-20% of time) and 5 (16.7%) respondents declared to have “never” (0%) been alerted on account of a written prescription necessitating an alteration.

Assessment of the definition of a prescribing error and types of events

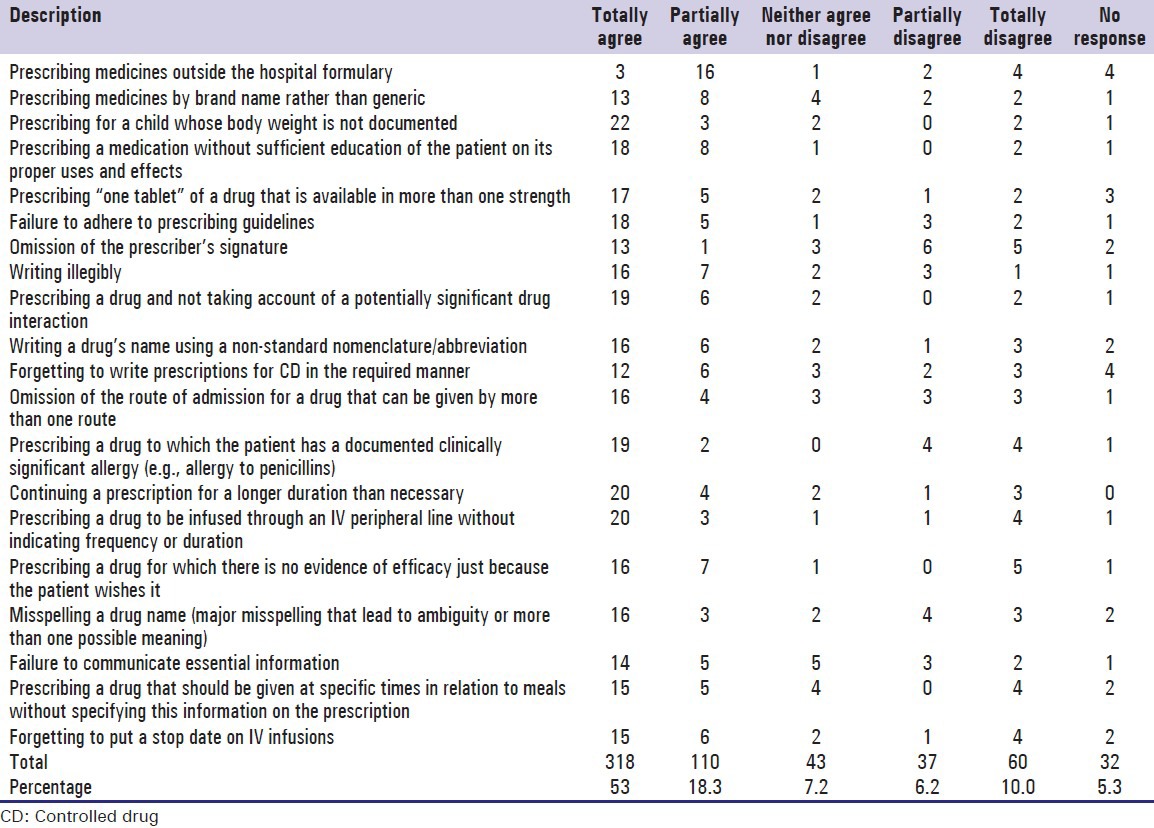

Seventeen (56.7%) respondents totally agreed with the Dean et al. definition of a clinically meaningful prescribing error. Eight (26.7%) partially agreed with the definition while 1 (3.3%) respondent each neither agreed nor disagreed, partially disagreed and totally disagreed respectively. 2 (6.6%) respondents gave no response. Furthermore, the study solicited that respondents indicate the extent to which they agreed that a prescribing error had occurred in the 20 scenarios described. The responses are presented in Table 1 below. Overall, of the events described, there was a 53% total agreement by respondents that a prescribing error had occurred, 18.3% partially agreement and a 10% totally disagreement that a prescribing error had occurred.

Table 1.

Extent to which respondents agreed that a prescribing error had occurred

Reasons for prescribing lapses

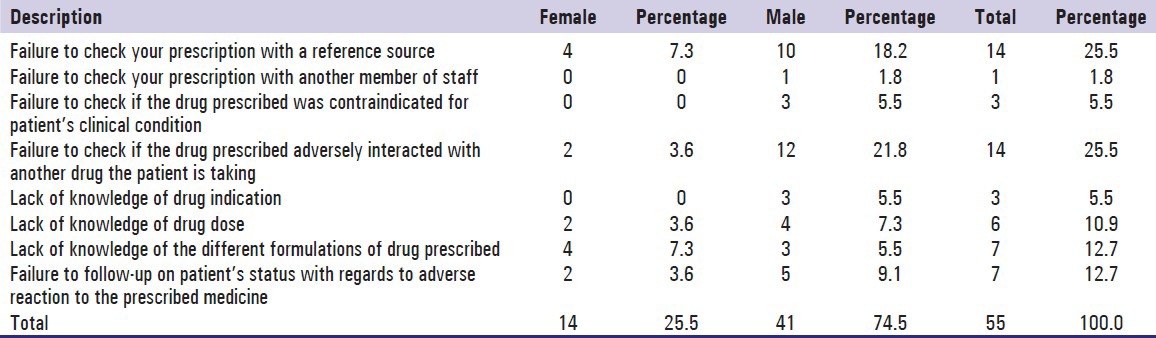

It is expected that rules for correct prescribing be followed at all times. The responses on reasons for prescribing errors commonly made and types encountered in practice by respondents are given in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Most common reasons for types of mistakes encountered or self-made

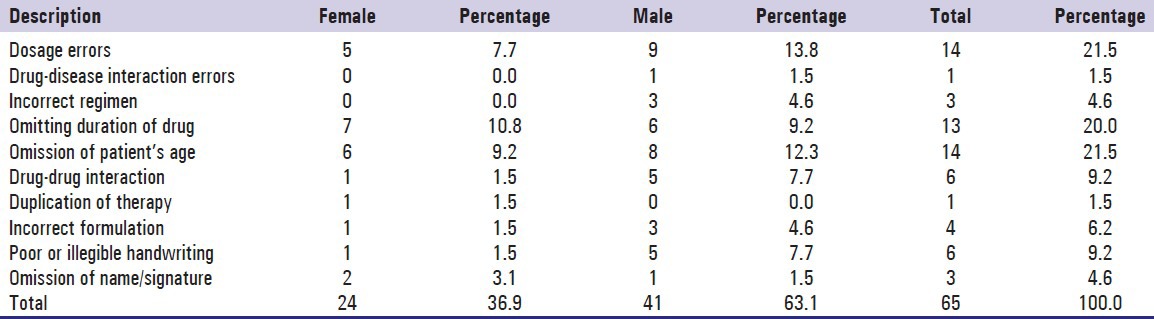

Table 3.

Most common types of errors made by respondents

Factors contributing to prescribing errors

Factors that could contribute to the possibility of prescribing errors occurring in the practice environment were sought. Respondents considered workload (23, 76.7%), multitasking (19, 63.3%), rushing (18, 60%) and tiredness or stress (16, 53.3%) as important contributory factors. Other factors mentioned were distraction (11, 36.7%), low morale (9, 30%), unfamiliar patient, busyness and no senior support (8, 26.7%) each, being nervous or confused (5, 16.7%) and time in the day (2, 6.7%).

Prescription writing confidence

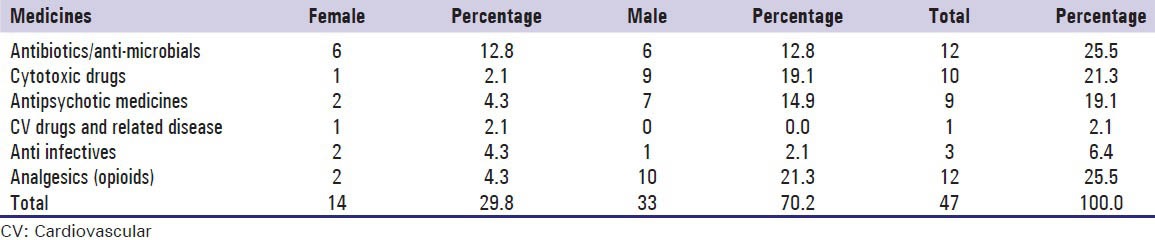

In order to assess the extent of clinical exposure on prescribing confidence, respondents were asked to rate their level of confidence when prescribing unsupervised, from a specified list of drugs. Table 4 shows the list of drugs they felt least confident prescribing when not supervised. Antibiotics/Antimicrobials, analgesics (opioids/non-opioids), cytotoxics and antipsychotics ranked highest amongst the drugs rated.

Table 4.

List of drugs that respondents were least confident prescribing

Discussion

All the interns reported to have had experience writing prescriptions with a majority claiming to be involved in prescribing medicines every day or more. Thus, they were already familiar with prescription writing process as a result of their clinical exposure to patient care. However, knowing what drug to prescribe to a patient did not necessarily translate to a good prescription.

Responses from these interns indicated a low self-awareness of making prescription errors. Up to 80% of the respondents felt they seldom or rarely made a prescription error which is contrary to reports of studies that focused on prescribing by junior doctors.[12,13,15] This suggests that their knowledge of what constitutes a prescribing error needs to be updated, thus highlighting an educational gap. They may have perceived themselves sufficiently prepared to prescribe rationally. However, this perception did not correlate with the high proportion who did not totally agree with the definition of a clinically important prescribing error as presented by Dean et al.[14] Previous studies have shown that the prescribing knowledge of new graduates of medical schools in Nigeria did not correlate with their prescribing skills.[21] Practical prescribing and regular assessment of prescribing skills are rarely practiced during undergraduate teaching.[22,23] Only the theoretical knowledge of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics are imparted in medical teaching.

A close look at the respondents’ self-rating of extents to which they agreed that a prescribing error had occurred reveal that about half (53%) partially agreed that prescribing medicines outside the hospital formulary constituted a prescribing error [Table 1]. Failure to crosscheck prescriptions with a reference source was also highly rated as a common reason for prescribing mistakes [Table 2]. Referring to reference sources/drug formularies for prescribing information has been reported as an important step to preventing adverse drug reactions.[24] It is of concern that interns do not consider prescribing medicines within the hospital formulary as important. Related to this is that less than half of respondents totally agreed that prescribing medicines by brand names rather than generics constituted a prescribing error. The formulary provides a reference standard to the hospital's prescribers toward ensuring safe and good quality supply management of medicines procured by the pharmacy department, at a minimum/affordable cost to individuals and is drawn from the national essential drug list. The implication is that respondents are likely to prescribe drugs that are locally unavailable and are more expensive. This contradicts the World Health Organizations’ principles for rational prescribing.[25]

From respondents’ extent of agreement to the 20 listed scenarios [Table 1], it is difficult to recommend all the standards for application at a given hospital even though more than 50% of the events received total agreement. It may be argued that practice situations, pattern of disease, approach to disease management, medicine administration processes, medication utilization and prescribing pattern vary from one country to another and may not all be applicable to a local setting. This observation however underscores the importance of standardizing the prescription writing process in Nigeria.

Although, the Nigeria standard treatment guideline[26] enumerates the essential elements of a prescription order to include identity of prescriber and patient in full, it is interesting to note that only 43% of the respondents agreed that omitting the prescriber's signature on a prescription order constituted a prescribing error. This underscores the need for education as it highlights the low perception of the importance of this requirement. Studies have reported the tendency of prescribers to omit such important details in prescription orders written in the hospital setting.[4,19] Internship is a period of medical apprenticeship, under the supervision by senior doctors. During this training, it is expected that interns would pick up some prescribing habits and skills through informal association with other doctors. A culture of omitting prescriber signature or name on orders is inappropriate and suggests that observing such in the practice environment may have led interns to believe this is of low importance. It is essential to correct this notion.

Writing prescriptions for controlled drugs (CD) in the required manner is another issue of concern. In the Nigeria setting, because pharmacists generally have not been assertive in ensuring that the proper protocols are adhered to, many irregularities abound in prescription orders for these categories of medicines. If the protocols for CD prescribing are not strictly adhered to and taught, little wonder if interns do not see the value of this. Furthermore, this study has revealed the need for standardization of how drugs are prescribed and documented in the hospital setting as a way to mitigate errors arising from poor prescription writing.

Workload was cited as the major factor contributing to prescribing errors. Other closely related factors were multitasking and rushing. Similar findings have been reported by other researchers.[7,10,11,12,27] Lack of knowledge of the drug was not a major reason for prescribing errors. Common reasons encountered or made by respondents were a failure to check prescriptions with a reference source or to check if the drug prescribed adversely interacted with other medicines the patient is taking. It can be overwhelming for these inexperienced doctors to have the in-depth pharmacologic knowledge required to treat patients along with identifying and preventing the opportunities for drug-drug interactions, drug-disease incompatibilities and allergies.[28]

Dosage errors and omitting to write patient's age topped the list of common types of prescribing errors made by respondents [Table 3]. This was followed by omitting to give a duration or length of time for taking a prescribed drug. These lapses are common in the hospital setting in Nigeria.[4,18,19] Junior doctors feel incompetent to write duration on prescribed medicines in the hospitalized patient because the conventional practice was to review patient's progress during the daily medical rounds. This however encourages unintended extension of administration due to the possibility of forgetting to stop the prescribed drug. Interestingly, duplication of therapy (prescribing two or more drugs from the same therapeutic class) and drug-disease interaction were the least common types of prescribing errors by respondents.

Respondents were least confident to prescribe antibiotics/antimicrobials, opioid analgesics and cytotoxics [Table 4]. This tended to reflect the pattern of ailment they had not yet been exposed to and possibly on their knowledge of potential adverse effects of these drugs when prescribed in error. It is interesting that antimicrobials are included in this list considering the high rate of use of this drug category in the study hospital[19] and society at large[29] prudence and caution in prescribing antibiotics is appropriate.

Confident prescribing apparently will depend on clinical exposure during the intern year. The more the number of clinical rotations, the more confident the respondents will be expected to be at prescribing. Confidence in prescribing comes with practice, responsibility and familiarity with frequently used drugs on the ward and adequate supervision by senior colleagues.[30]

The need for a standardized approach to what constitutes an acceptable prescription in the Nigeria setting cannot be over-emphasized. Such a framework will be designed to be acceptable to our prescribers and to which they can be meaningfully evaluated. Good quality prescribing will not be achieved if individual prescribers are allowed to define what correct prescribing is on their own. The involvement of pharmacists and other health care professionals in developing practice standards for good quality prescribing to which prescribers can adhere and upon which they can be evaluated is pertinent.

This study considered a good spread of intern doctors in the different specialties of rotation but results cannot be generalized as the views of all interns trained in Nigeria. Although, a statistically significant gender balance was not achieved in the study sample, it is unlikely that the result obtained would change significantly if a gender balance was achieved. The study relied on self-assessment by respondents which may be subject to systematic bias. Possible skewing may have resulted from using the 20 clinical scenarios. Nevertheless, this study gives some insight into the knowledge and attitude of intern doctors to prescribing errors and offers openings for further research in this area.

Conclusion

This study has shown the gaps in the knowledge that intern doctors have about prescription errors. Inadequate knowledge or competence and incomplete information about clinical characteristics of individual patients can result in prescribing faults, including the use of potentially unfamiliar medications. Interns have a low self-awareness of prescribing errors and would likely benefit from theoretical and practical teaching on what constitutes a properly written prescription with frequent assessment of knowledge and skills acquired. This would likely improve their confidence in rational medication prescribing during and after their internship training. An unsafe working environment and inadequate supervision have also been identified as important underlying factors that contribute to prescription errors.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to all the intern doctors who participated in this study.

Appendix

Events that constitute a prescribing error

(Dean et al., 2000)

Errors in decision making

-

Prescription inappropriate for the patient concerned

- Prescribing a drug for a patient for whom, as a result of a co-existing clinical condition, that drug is contraindicated e.g., metformin for a patient with CrCl < 60 mL/min; Beta adrenergic -blocker to asthma patients

- Prescribing a drug to which the patient has a documented clinically significant allergy e.g., amoxiclav for a patient with penicillin allergy

- Prescribing a drug and not taking into account a potentially significant drug-interaction e.g., Concomitant administration of artemether/lumefantrine and azithromycin (a macrolide antibiotic) => Q-wave elongation, a hazardous interaction; Warfarin + diclofenac (NSAIDs) => increased risk of bleeding

- Prescribing a drug in a dose which is inappropriate for the patient's renal function e.g., clarithromycin, imipenem, ceftazidime. dose reduction required in renal impairment

- Prescribing a drug in a dose below that recommended for the patient's clinical condition e.g., amoxiclav 625 mg b.d instead of 8 hourly in respiratory tract infections (RTI)

- Prescribing a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, in a dose predicted to give serum levels significantly above the desired therapeutic range e.g., theophylline; plasma –theophylline concentration for optimum response is 10.20 mg/L

- Prescribing 2 drugs for the same indication when only one drug is necessary e.g., amoxicillin and cefuroxime concurrently for RTI when one would be adequate

- Prescribing a drug for which there is no indication for that patient e.g., antibiotics for viral infections

- Not altering the dose following steady state serum levels significantly outside the therapeutic range e.g., digoxin dose should state concentration has been reached

- Continuing a drug in the event of a clinically significant ADR e.g., statins and muscle effects

-

Pharmaceutical issues

- Prescribing a drug to be given by IV infusion in a diluent that is incompatible with the drug prescribed e.g., nitrofrusside injection administered in a plastic IV container

- Prescribing a drug to be infused via an IV peripheral line, in a concentration greater than that recommended for peripheral administration.

Errors in prescription writing

-

Failure to communicate essential information

- Prescribing a drug, dose or route that is not that intended

- Prescribing a medicine and omitting the dose, frequency, route or duration of use

- Writing illegibly

- Writing a drug's name using abbreviations or other non-standard nomenclature

- Writing an ambiguous medication order

- Prescribing ‘one tablet’ of a drug that is available inmore than one strength of a tablet

- Omission of the route of administration for a drug that can be given by more than one route

- Prescribing a drug to be given by intermittent IV infusion, without specifying the duration over which it is to be infused

- Omission of prescriber's identity (name/signature)

-

Transcription errors

- On admission to hospital, unintentionally not prescribing a drug that the patient was taking prior to their admission

- Transcribing a medication order incorrectly when re-writing a patient's drug chart

- Continuing another doctor's prescribing error when writing a patient's drug chart on admission to hospital

- Writing ‘miligrams’ when ‘micrograms’ was intended (or vice-versa)

- Writing a prescription for discharge medication that un-intentionally deviates from the medication prescribed on the in-patient drug chart

Situations that may be considered prescribing errors, depending on individual clinical situation

Prescribing a drug in a dose above the maximum dose recommended in the BNF or other reference book or guideline

Misspelling a drug name (major misspellings that lead to ambiguity)

Prescribing a drug that cannot readily be administered using the dosage forms available

Prescribing a dose regimen (dose/frequency) that is not recommended for the formulation prescribed

Continuing a prescription for a longer duration that necessary

Prescribing a drug that should be given at specific times in relation to meals without specifying this information on the prescription

Unintentionally not prescribing a drug for a clinical condition for which medication is indicated.

Situations that should be excluded as prescribing errors

Prescribing by brand name (as opposed to generic name)

Prescribing a drug without informing the patient of its uses and potential side effects

Prescribing a drug for which there is no evidence of efficacy, because the patient wishes it

Prescribing a drug not in the hospital formulary

Prescribing contrary to hospital treatment guidelines

Prescribing contrary to national treatment guidelines

Prescribing for an indication that is not a drug's product license

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Aronson JK. Medication errors: Definitions and classification. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:487–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seden K, Kirkham JJ, Kennedy T, Lloyd M, James S, McManus A, et al. Cross-sectional study of prescribing errors in patients admitted to nine hospitals across North West England. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002036. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002036. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ajemigbitse AA, Omole MK, Erhun WO. Medication prescribing errors in a tertiary teaching hospital in Nigeria: Types, prevalence and clinical significance. West Afr J Pharm. 2013;24:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al Khaja KA, Al-Ansari TM, Sequeira RP. An evaluation of prescribing errors in primary care in Bahrain. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:294–301. doi: 10.5414/cpp43294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corona-Rojo JA, Altagracia-Martínez M, Kravzov-Jinich J, Vázquez-Cervantes L, Pérez-Montoya E, Rubio-Poo C. Potential prescription patterns and errors in elderly adult patients attending public primary health care centers in Mexico City. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:343–50. doi: 10.2147/cia.s5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dornan T, Ashcroft D, Heathfield H, Lewis P, Miles J, Taylor D, et al. In depth investigation into causes of prescribing errors by foundation trainees in relation to their medical education. EQUIP study A report to the General Medical Council. 2009. [Last accessed on 2010 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/FINAL_Report_prevalence_and_causes-of_prescribing_errors.pdf-28935150.pdf .

- 8.Ryan C, Davey P, Francis J, Johnston M, Ker J, Lee AJ, et al. The prevalence of prescribing errors amongst junior doctors in Scotland. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;109:35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: Their incidence and clinical significance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:340–4. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin BD, Reynolds M, Shebl NA, Burnett S, Jacklin A. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: A three-centre study of their prevalence, types and causes. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:739–45. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.117879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: A prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1373–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross S, Ryan C, Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Ker JS, et al. Perceived causes of prescribing errors by junior doctors in hospital inpatients: A study from the PROTECT programme. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:97–102. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross S, Bond C, Rothnie H, Thomas S, Macleod MJ. What is the scale of prescribing errors committed by junior doctors? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:629–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care. 2000;9:232–7. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshikoya KA, Senbanjo IO, Amole OO. Interns’ knowledge of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics after undergraduate and on-going internship training in Nigeria: A pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldacre MJ, Taylor K, Lambert TW. Views of junior doctors about whether their medical school prepared them well for work: Questionnaire surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:78. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revised Edition. Petruvanni Company Ltd, Lagos; 1993. Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria. Guidelines on Minimum Standards of Medical and Dental Education in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshikoya KA, Chukwura HA, Ojo OI. Evaluation of outpatient paediatric drug prescriptions in a teaching hospital in Nigeria for rational prescribing. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 2006;7:183–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajemigbitse AA, Omole KM, Erhun WO. An evaluation of the types, prevalence and severity of prescribing errors in National Hospital Abuja. Arch Niger Med Med Sci. 2011;8:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erhun WO, Adekoya OA, Erhun MO, Bamgbade OO. Legal issues in prescription writing: A study of two health institutions in Nigeria. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshikoya KA, Bello JA, Ayorinde EO. Prescribing knowledge and skills of final year medical students in Nigeria. Indian J Pharmacol. 2008;40:251–5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.45150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobaiqy M, McLay J, Ross S. Foundation year 1 doctors and clinical pharmacology and therapeutics teaching. A retrospective view in light of experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:363–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02925.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton A, Webb DJ, Maxwell SR. Undergraduate preparation for prescribing: The views of 2413 UK medical students and recent graduates. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:128–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshikoya KA. Adverse drug reaction in children: Types, incidences and risk factors. Niger J Paediatr. 2006;33:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vries TP, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, Fresle DA. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 1994. Guide to Good Prescribing: A Practical Manual. WHO/DAP/94.11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.1st ed. Published by the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja-Nigeria in Collaboration with the World Health Organization; 2008. Standard Treatment Guideline for Nigeria; pp. 206–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coombes ID, Stowasser DA, Coombes JA, Mitchell C. Why do interns make prescribing errors? A qualitative study. Med J Aust. 2008;188:89–94. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan C, Donnelly K, Somani S. Needs and opportunities for achieving optimal outcomes from the use of medicines in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:1086–96. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enato EF, Aghomo OF, Oparah AC, Odili UV, Etaghene BE. Drug utilization in a Nigeria rural community. J Med Biomed Res. 2003;2:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molokwu CN, Sandiford N, Anosike C. Safe prescribing by junior doctors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:615–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]