Summary

Recent progress in skeletal molecular biology has led to the clarification of the transcriptional mechanisms of chondroblastic and osteoblastic lineage differentiation. Three master transcription factors—Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix—were shown to play an essential role in determining the skeletal progenitor cells' fate. The present study evaluates the expression of these factors in 4 types of benign bone tumors—chondromyxoid fibroma, chondroblastoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma—using immunohistochemistry and tissue microarrays. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma showed strong nuclear expression of Osterix and Runx2. In contrast, only a few chondroblastomas showed positive nuclear expression of Osterix. Strong nuclear expression of Sox9 was detected in all chondroblastomas, whereas nearly half of the osteoblastomas showed focal weak cytoplasmic expression of Sox9.

Keywords: Master regulatory proteins, Skeletal development, Benign bone tumors

1. Introduction

The identification of master regulatory genes and their encoded proteins, such as SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 9 (Sox9), runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), and Sp7 transcription factor (Osterix), has provided new insights into molecular regulation of skeletal development [1]. These genes are expressed in a lineage-specific manner controlling differentiation of skeletal progenitor cells and may represent novel markers helpful in the differential diagnosis of bone tumors.

Sox9 encodes an HMG-box transcription factor essential for mesenchymal condensation of osteoprogenitor cells as the initiating step in chondroblastic lineage differentiation [2]. It is required for the expression of such cartilage specific matrix proteins as collagen type II, IX, XI, and aggrecan [3,4].

Runx2, also referred to as Cbfa1 (anti–core-binding factor α1), regulates the recruitment of preosteoblastic cells from multipotent mesenchymal cells [5]. It also plays a critical role in chondrocyte maturation and cartilage vascularization [6].

Osterix is a newly discovered transcription factor that is essential for osteoblastic differentiation and bone formation [7]. Its expression is controlled by the Runx2 protein that binds to the promoter of the Osterix gene and up-regulates its expression [8,9]. The human homologue of Osterix transcription factor, specificity protein-7 (Sp7), was first identified in the murine pluripotent myoblastic cells grown in vitro [7]. Similar to murine protein, human Osterix contains a zinc finger motive of 85 amino acids that recognizes GC− and GT− boxes [7].

Animal studies indicate that Sox9 is required for the recruitment of skeletal progenitor cells that are bipotential and capable of producing both main skeletal lineages: chondroblastic and osteoblastic (Fig. 1A) [10]. In general, the low level of Runx2 does not affect the differentiation of chondrocytes [10]. The skeletal progenitor cells that express Runx2/Cbfβ are still bipotential [11]. They differentiate into functional osteoblasts in the presence of Osterix that commit cells to the osteoblastic lineage by suppressing the expression of Sox9 [12].

Fig. 1.

Construction of microarray and control studies. A, The role of Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix in osteoblastic and chondroblastic differentiated pathways (modified from Nakashima et al. Trends Gene 2003;19:458–466) [11]. B, Representative cores corresponding to 1 to 4 chondromyxoid fibroma, chondroblastoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma respectively. C to F, Representative photomicrographs of the cores corresponding to chondromyxoid fibroma, chondroblastoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma respectively. G, Whole-mount section of mouse embryo (embryonic day 15) stained with H&E. H, Expression of Sox9 in proliferating chondrocytes of skeletal developmental centers. I to J, Expression of Runx2 and Osterix, respectively, primarily in the perichondrium of the skeletal developmental centers (C–F: H&E, ×300; H-J: DAB and hematoxylin, ×300).

Here, we report on the expression patterns of the 3 master regulatory genes (Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix) in prototypic benign cartilage and bone forming tumors using immunohistochemistry and tissue microarray (TMA) technology.

2. Materials and method

Cases were retrieved from pathology files and used for this study according to the laboratory protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. The clinicopathologic features and demographic data of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of clinicopathologic data for the benign bone cartilage and tumors used in this study

| Tumor type | Sex (M/F) |

Median age (range in years) |

Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | 5/3 | 30 (13–51) | Femur 3 |

| Humerus 2 | |||

| Tibia 2 | |||

| Pelvis 1 | |||

| Chondroblastoma | 8/0 | 26 (16–72) | Femur 3 |

| Humerus 2 | |||

| Calcaneous 2 | |||

| Pelvis 1 | |||

| Osteoblastoma | 10/2 | 20.5 (17–46) | Spine 9 |

| Talus 2 | |||

| Maxilla 1 | |||

| Osteoid Osteoma | 9/3 | 14.5 (9–37) | Femur 6 |

| Tibia 4 | |||

| Fibula 2 |

A TMA was constructed as previously described [13]. In brief, hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] slides from 40 bone tumors were reviewed: 8 chondromyxoid fibromas, 8 chondroblastomas, 12 osteoid osteomas, and 12 osteoblastomas. All tissue samples, before being embedded in paraffin, were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 4 hours and were decalcified in 10% formic acid for 12 to 24 hours. The decalcification process was monitored by specimen radiography. The most representative well-preserved foci of the tumor were selected and marked. The donor paraffin blocks were punched in the areas of interest using microarray instrument (Beecher Instruments, Inc, Sun Praire, WI), and 5-mm 1 to 3 cores of the each tumor tissue were transferred to a recipient block. The recipient microarray block contained a total of 112 cores corresponding to 40 tumors (Fig. 1B–F). A section of mouse embryo (embryonic day 15) was used as the internal control for TMA (Fig. 1G) [7].

For immunohistochemical stains, deparaffinized 5-µm sections from TMA and mouse embryo were stained with the following primary antibodies: anti-Sox9, 1:100 (antibody AB5535; Chemicon, Temecula, CA); anti-Runx2, 1:100 (antibody R 9403; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO); and anti-Osterix, 1:100, developed by us [7]. Antigen retrieval was performed for all markers using microwave heating at level 10 for 10 minutes in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Dako, Carpinteria, CA). In addition, sections stained with anti-Osterix antibody were pretreated with 1% trypsin. After blocking of endogenous peroxidase, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 60 minutes at room temperature. The bound primary antibodies were visualized by avidinbiotin complex assay (Dako) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a chromogen (Dako) and hematoxylin as a counterstain. Sections in which primary or secondary antibodies were omitted and replaced with normal serum from the same species served as negative controls. The secondary antibody was omitted to test the potential nonspecific staining by color detection reagents. The staining was interpreted as positive or negative and nuclear or cytoplasmic. The intensity of positive staining was graded as mild, moderate, or strong.

3. Results

The expression patterns of Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix in the mouse embryo of embryonic day 15 were used as a control and were consistent with their role as master regulatory proteins of skeletal development (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, the expression of Sox9 was present in the central zones of proliferative chondrocytes (Fig. 1H), whereas Osterix and Runx2 were predominantly expressed in the perichondrial cells that would eventually differentiate into osteoblasts (Fig. 1I, J).

3.1. Expression of Sox9

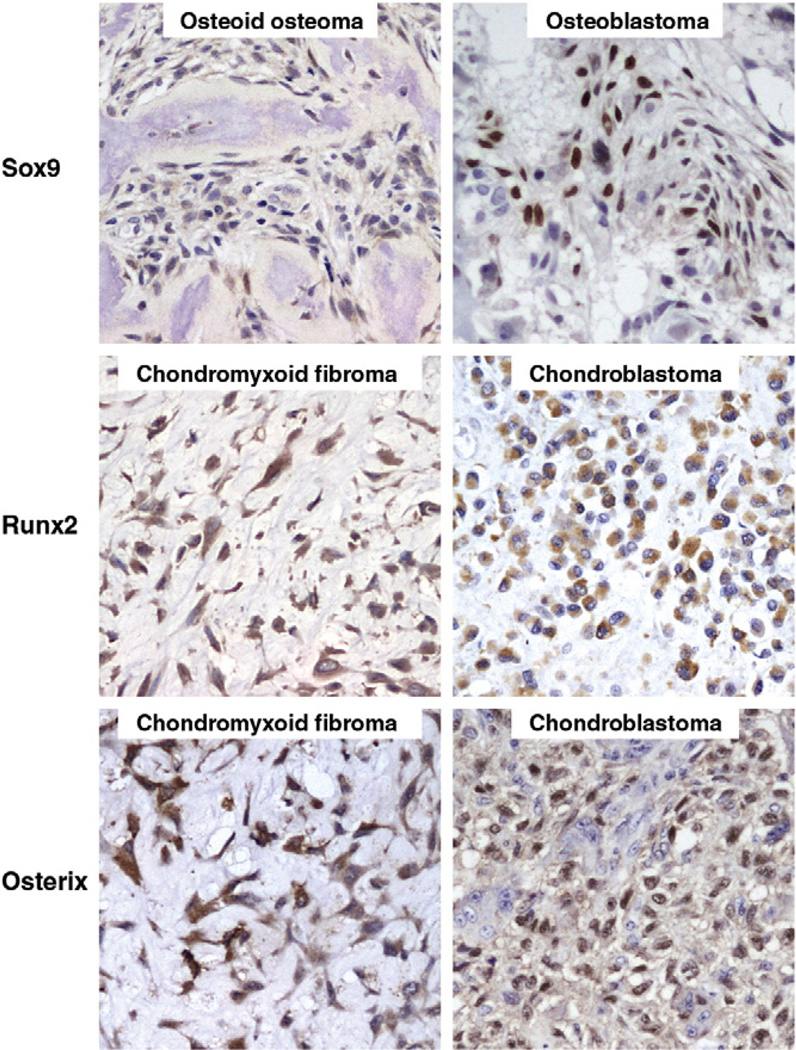

Strong nuclear expression of Sox9 was present in most of the chondromyxoid fibromas and chondroblastomas. Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas, in general, did not show expression of Sox9. In 7 of the 8 chondromyxoid fibromas, a strong nuclear expression of Sox9 was present. The typical stellate or spindle cells in the myxoid background, as well as the hypercellular areas, showed strong nuclear expression of Sox9 (Fig. 2). In one case of chondromyxoid fibroma, which was negative for Sox9, the tissue sample in the microarray was composed mostly of hypocellular myxoid matrix with only a few neoplastic cells. All 8 chondroblastomas exhibited strong nuclear expression of Sox9. It was expressed in mononuclear chondroblastic cells, whereas multinucleated giant cells were negative. All 12 osteoid osteomas were negative for Sox9. Weak nuclear expression of Sox9 was occasionally observed in the osteoblasts around woven bone trabeculae (Fig. 3). In addition, 5 of 12 osteoblastomas showed focal weak cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of Sox9 in the intertrabecular spindle stromal cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Expression of Sox9, Osterix, and Runx2 in benign cartilage and bone forming tumors. Strong nuclear expression of Sox9 is evident in chondromyxoid fibroma and chondroblastoma. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma show strong nuclear expression of Runx2 and Osterix (DAB and hematoxylin, ×300).

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic dichotomy in benign cartilage and bone forming tumors. Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas show focal expression of Sox9. Focal diffuse cytoplasmic expression of Runx2 and Osterix is present in chondromyxoid fibroma and chondroblastoma. (DAB and hematoxylin, ×300).

3.2. Expression of Runx2

A strong nuclear expression of Runx2 was present in most of the osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas, whereas chondromyxoid fibromas and chondroblastomas generally showed no expression of Runx2 (Fig. 2). From a total of 8 cases each, 3 chondromyxoid fibromas and 4 chondroblastomas showed focal weak cytoplasmic expression of Runx2 (Fig. 3). All 12 osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas showed strong nuclear expression of Runx2. Both osteoblasts lining bony trabeculae and intertrabecular stromal cells were positive for Runx2.

3.3. Expression of Osterix

The expression pattern of Osterix in benign cartilage and bone forming tumors was similar to that of Runx2. Strong nuclear expression of Osterix was present in most of the osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas (Fig. 2). Chondromyxoid fibromas and chondroblastomas were, in general, negative for Osterix. In 7 of 8 chondromyxoid fibromas, there was no expression of Osterix (Fig. 2). In the remaining single chondromyxoid fibroma, a focal weak cytoplasmic expression of Osterix was found (Fig. 3). Similarly, 3 of the 8 chondroblastomas showed focal weak nuclear expression of Osterix in the spindle fibroblast-like cells (Fig. 3). The mononuclear chondroblastic cells of the tumor were negative for any nuclear expression of Osterix in the same 3 cases. The remaining 5 cases of chondroblastomas showed no expression of Osterix (Fig. 2). All 12 osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas showed strong nuclear expression of Osterix. The osteoblastic cells lining the osteoid trabeculae and intertrabecular spindle cells were equally strong in expressing Osterix (Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

Our study showed that benign cartilage forming tumors, such as chondromyxoid fibromas and chondroblastomas, expressed a cartilage lineage regulator, Sox9. These tumors, in general, did not express Runx2 and Osterix. In contrast, the benign forming tumors, osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas, showed strong expression of osteoblastic lineage regulatory genes such as Osterix and Runx2 and were, generally, negative for Sox9.

Sox9 is one of the earliest transcription factors expressed in pluripotential mesenchymal cells undergoing condensation that give rise to both chondrogenic and osteogenic lineages [2,10]. Expression of Sox9 is essential for chondrocytic differentiation and directly regulates the expression of cartilage-specific genes in mature chondrocytes [3,4]. Mice with heterozygotic mutant and conditional knockouts of Sox9 display perinatal lethality with cleft palate or hypoplasia along with a distortion of all cartilage-derived skeletal structures [2]. Heterozygous mutations and deletions in and around Sox 9 were documented in campomelic dysplasia (CMPD1) in humans, a rare syndrome associated with skeletal malformations [14,15].

Runx2 is involved in the divergence of osteoprogenitor cells into the osteoblastic pathway [10]. Runx2 regulates its downstream partner protein, Osterix, which is crucial for maturation of preosteoblasts into functioning osteoblastic cells [7,10].

Overexpression of Runx2, in transgenic mice, results in defective osteoblastic maturation with generalized osteopenia and multiple fractures [16,17]. Thus, the correct dose of Runx2 is essential for harmonious bone formation and skeletal development. Cytoplasmic expression of Runx2 in tumor cells is rarely reported and may reflect the presence of disrupted or unstable protein forms [18].

Under stimulation of Osterix, preosteoblasts mature to functional osteoblasts expressing Col1a1, bone sialoprotein, osteocalcin, and other genes facilitating the formation of mineralized bone [7,9]. Osterix-null mouse embryos have normal cartilage, but they completely lack bone formation in the endochondral and membranous skeletal elements [9]. Thus, Osterix is a critical factor controlling the fate of osteoprogenitor cells, directing them toward fully functional osteoblasts capable of producing bone matrix [8,19].

We have previously shown that Sox9 is uniformly expressed in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma and can be used in a differential diagnosis of small cell malignancies [20]. Moreover, its expression in chondroblastoma and chondromyxoid fibroma was confirmed by a recent immunohistochemical study [21]. In contrast to benign cartilage and bone forming tumors, conventional, mesenchymal, and clear cell chondrosarcomas show phenotypic dichotomy and coexpress Runx2 and Sox9 [22]. Similarly, osteosarcomas, in addition to Runx2 and Osterix, coexpress Sox 9 [23,24]. The expression of Runx2 in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma was predominantly seen in the undedifferentiated small cell component of the tumor. In conventional chondrosarcoma, high levels of expression of Runx2 correlated with more cellular areas and high histologic grade of the tumor [22].

Several studies indicate that the skeletal master regulatory genes are involved in tumorigenesis. Runx2 binds to specific regulatory elements of the human Bax and acts as a proapoptotic factor in osteosarcoma [25]. Interestingly, the overexpression of Runx2 in osteosarcoma was shown to be associated with aggressive clinical behavior and strongly correlates with the development of metastasis [26]. This is in keeping with functional studies showing that the terminal osteoblastic differentiation controlled by Runx2 is disrupted in osteosarcoma [27]. Preliminary data indicate that Osterix overexpression suppresses growth and the development of lung metastases in murine models of osteosarcoma [28]. In addition, its overexpression decreases osteolytic activity of osteosarcoma cells by down-regulating interleukin-1α [29]. It appears that Runx2 contributes to malignant transformation through a dominant oncogene-like activity associated with poor differentiation and aggressive clinical behavior. In contrast, Osterix has tumor suppressor–like properties inhibiting growth of malignant cells and decreasing the development of metastasis.

This study provides evidence that the expression of Sox9 in benign cartilage tumors is consistent with their commitment to the early phases of cartilage differentiation. Occasional focal cytoplasmic expression of Runx2 and Osterix in chondroblastomas may reflect aberrant cytoplasmic localization of these proteins documented in experimental systems or may represent nonspecific staining. The presence of cells with focal nuclear expression of Runx2 and Osterix in chondroblastomas may reflect the nonhomogenous nature of these tumors and uncertain lineage commitments of their individual cells. Similarly, strong expression of Osterix and Runx2 in benign bone tumors signifies their osteoblastic lineage differentiation reflecting early phases of osteoid production upstream of mature bone formation. Occasional nuclear expression of Sox9 in osteoblastoma may constitute the uncertain lineage fidelity of its individual cells with the possibility of divergent chondroblastic differentiation that is occasionally seen in these tumors [30]. The presence of focal stromal cells in these tumors expressing Sox9 was not associated with microscopic features of cartilage matrix production. The expression of Sox9 was restricted to individual scattered stromal cells not associated with osteoid deposition in these tumors. In general, there was no correlation between phenotypic dichotomy of individual tumor cells in both cartilage and bone forming tumors and the anatomical sites or age of patients. In summary, the 3 master regulatory proteins, Sox9, Runx2, and Osterix, represent novel markers helpful in assessing chondroblastic and osteoblastic lineage differentiation of bone tumors. Their studies in a full spectrum of benign and malignant bone tumors may provide new insights helpful in the differential diagnosis of these rare and diagnostically challenging conditions.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Kim-Ahn Vu for the graphic designs, and Stephanie Garza and Virginia Hurley for administrative and secretarial assistance.

References

- 1.Zou L, Zou X, Li H, et al. Molecular mechanism of osteochondroprogenitor fate determination during bone formation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;585:431–441. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34133-0_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bi W, Deng JM, Zhang Z, et al. Sox9 is required for cartilage formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22:85–89. doi: 10.1038/8792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebvre V, Huang W, Harley VR, et al. SOX9 is a potent activator of the chondrocyte-specific enhancer of the pro alpha1(II) collagen gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2336–2346. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefebvre V, Li P, de Crombrugghe B. A new long form of Sox5 (L-Sox5), Sox6 and Sox9 are coexpressed in chondrogenesis and cooperatively activate the type II collagen gene. Embo J. 1998;17:5718–5733. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, et al. Requisite roles of Runx2 and Cbfb in skeletal development. J Bone Miner Metab. 2003;21:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00774-002-0408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinoi E, Bialek P, Chen YT, et al. Runx2 inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy through its expression in the perichondrium. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2937–2942. doi: 10.1101/gad.1482906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, et al. The novel zinc finger– containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishio Y, Dong Y, Paris M, et al. Runx2-mediated regulation of the zinc finger Osterix/Sp7 gene. Gene. 2006;372:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koga T, Matsui Y, Asagiri M, et al. NFAT and Osterix cooperatively regulate bone formation. Nat Med. 2005;11:880–885. doi: 10.1038/nm1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiyama H, Kim JE, Nakashima K, et al. Osteo-chondroprogenitor cells are derived from Sox9 expressing precursors. PNAS. 2005;102:14665–14670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504750102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakashima K, de Crombrugghe B. Transcriptional mechanisms in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Trends Gene. 2003;19:458–466. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karsenty G. Transcriptional control of skeletogenesis. Annu Rev Geonomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:183–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Tuziak T, Hu L, et al. Alterations in transcription clusters underlie development of bladder cancer along papillary and nonpapillary pathways. Lab Invest. 2005;85:532–549. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada Y, Nishimura G, Nagai T, et al. Mutation analysis of SOX9 and single copy number variant analysis of the upstream region in eight patients with campomelic dysplasia and acampomelic campomelic dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2882–2885. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDowall S, Argentaro A, Ranganathan S, et al. Functional and structural studies of wild type SOX9 and mutations causing campomelic dysplasia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24023–24030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enomoto H, Shiojiri S, Hoshi K, et al. Induction of osteoclast differentiation by Runx2 through receptor activator of nuclear factor– kappa B ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin regulation and partial rescue of osteoclastogenesis in Runx2−/− mice by RANKL transgene. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23971–23977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda S, Bonnamy JP, Owen MJ, et al. Continuous expression of Cbfa1 in nonhypertrophic chondrocytes uncovers its ability to induce hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation and partially rescues Cbfa1- deficient mice. Genes Dev. 2001;15:467–481. doi: 10.1101/gad.845101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terry A, Kilbey A, Vaillant F, et al. Conservation and expression of an alternative 3' exon of Runx2 encoding a novel proline-rich C-terminal domain. Gene. 2004;336:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baek WY, de Crombrugghe B, Kim JE. Positive regulation of adult bone formation by osteoblast-specific transcription factor osterix. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1055–1065. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehrli BM, Huang W, De Crombrugghe B, et al. Sox9, a master regulator of chondrogenesis, distinguishes mesenchymal chondrosarcoma from other small blue round cell tumors. HUM PATHOL. 2003;34:263–269. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konishi E, Nakashima Y, Iwasa Y, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis for Sox9 reveals the cartilaginous character of chondroblastoma and chondromyxoid fibroma of the bone. HUM PATHOL. 2010;41:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park HR, Park YK. Differential expression of runx2 and Indian hedgehog in cartilaginous tumors. Pathol Oncol Res. 2007;13:32–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02893438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lian JB, Stein GS, Javed A, et al. Networks and hubs for the transcriptional control of osteoblastogenesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakami T, Shimizu T, Kimura A, et al. Immunohistochemical examination of cytological differentiation in osteosarcomas. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10:475–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eliseev RA, Dong YF, Sampson E, et al. Runx2-mediated activation of the Bax gene increases osteosarcoma cell sensitivity to apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:3605–3614. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Won KY, Park HR, Park YK. Prognostic implication of immunohistochemical Runx2 expression in osteosarcoma. Tumori. 2009;95:311–316. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas DM, Johnson SA, Sims NA, et al. Terminal osteoblast differentiation, mediated by runx2 and p27KIP1, is disrupted in osteosarcoma. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:925–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao Y, Zhou Z, de Crombrugghe B, et al. Osterix, a transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation, mediates antitumor activity in murine osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1124–1128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao Y, Jia SF, Chakravarty G, et al. The osterix transcription factor down-regulates interleukin-1 alpha expression in mouse osteosarcoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:119–126. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorfman H, Czerniak B. Bone tumors, textbook of skeletal pathology. Philadelphia, AP: Mosby-Year Book, Inc; 1999. Chapter 4: benign osteoblastic tumors. [Google Scholar]