The treatment armamentarium for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has grown substantially over the last 15 years since the development of targeted biologic and non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs have broadened the treatment possibilities and changed how rheumatic disease experts approach the clinical management of RA. The goal of reducing disease activity to very low levels (or remission) is now realistic, and emerging evidence suggests that treating to achieve these targets enhances long term structural and quality of life outcomes.(1–7) Consequently, “treat to target” (TTT) has become an attractive concept in the clinical management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). TTT is generally defined as a treatment strategy in which the clinician treats the patient aggressively enough to reach and maintain explicitly specified and sequentially measured goals, such as remission or low disease activity. TTT is proactive, has a clear endpoint (the “target”), and can be operationalized as a specific treatment algorithm, simplifying the multitude of complex medication sequences that can be used to treat active RA. The emerging TTT paradigm is supported by findings from many randomized controlled clinical trials in the last decade, not designed as TTT strategy trials, that suggest the benefits of early aggressive treatment approaches.(5, 8, 9)

While TTT has many potential benefits, the rheumatology community needs to critically appraise its value in the treatment of RA. Put another way, is TTT a proven paradigm or a hypothesis requiring more complete testing? In this commentary, we first describe how TTT has been defined in RA and what data support its use. Second, we examine the conceptual roots of TTT, assessing how it has been used in conditions outside of rheumatology. Third, we examine current DMARD use patterns and barriers to TTT in clinical practice are examined. Fourth, we discuss data from the patients’ perspective relevant to TTT and set out a research agenda to address identified gaps in knowledge.

I. Treat to Target in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Over the past 10–15 years, several randomized controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that a TTT strategy can achieve superior clinical outcomes compared with usual care. Studies included to support evidence for TTT can be divided into randomized strategy trials, assessing the efficacy of treating to a specific target versus routine care in the comparator arm; and treatment target trials in which all treatment arms have a defined target, but different treatment strategies to reach the target are compared. All TTT trials have included relatively frequent assessment with recommendations for intensifying treatment when patients have not reached target. These trials (reviewed in Table 1) have been primarily conducted in Western Europe.(1–7, 10) The number of subjects included in TTT trials ranges from 96–508. Some of the trials required subjects in the TTT arm to be treated according to specific treatment algorithms and others allowed treating physicians to decide on treatments but required a specific disease activity goal. Almost all randomized at the subject level. Treating providers were not blinded to assignment group in most studies, but many of the trials employed blinded assessors. Duration of follow-up ranged from 6–36 months and few trials accounted for the clustering of subjects within practices.

Table 1.

Selected Treat to Target Randomized Controlled Trials in Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Reference | Study Cohort | Target | Algorithm for TTT; follow-up interval | Duration of follow-up (mos) | Randomization | Blinded assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy Trials (one group with a target and another without) | |||||||

| Grigor, 2004 (TICORA) (1) | N = 110; 2 National Health Service hospitals in UK | EULAR good response (DAS28 (ESR) <2.4 & change from baseline DAS by >1.2) at month 18 | Yes; 4 weeks | 18 | Patient-level | Blinded metrologist |

EULAR good response: TTT: 82% Control: 44% (p<0.0001) |

| Verstappen, 2007 (CAMERA) (2) | N = 299; 6 rheumatology departments in the Netherlands | >20% improvement of SJC and ESR, TJC, PGA at year 2 | Yes; 4 weeks | 24 | Patient-level | No; open-label trial |

DAS28 remission: TTT: 35% Control: 14% (p<0.001) |

| Fransen, 2005 (3) | N = 384; 24 rheumatology departments in the Netherlands. | DAS28 (ESR)<3.2 (low disease activity) at week 24 | No; none | 6 | Practice-level | Unclear from publication |

DAS28<3.2: TTT: 31% Control: 16% (p=0.028) |

| Symmons, 2005 (7) | N = 466; 5 rheumatology departments in England | No active tender or swollen joints; CRP < 2x ULN at year 3 | No; 4 months | 36 | Patient-level | Assessor blinding |

HAQ: TTT: 1.45 Control: 1.40 (p = NS) |

| Treatment Target Trials (all groups with target but strategies to achieve target differ) | |||||||

| Mottonen, 1999 (FIN-RACo) (36) | N = 195; from Finland | Induction of ACR-remission* at year 1 | No; 12 weeks | 24 | Patient-level | No; open-label trial | ACR Remission Criteria: Triple therapy: 38% Monotherapy: 17% |

| Saunders, 2008 (5) | N = 96; 3 National Health Service hospitals in UK | DAS28(ESR) <3.2 (low disease activity) at year 1 | Yes; 12 weeks | 12 | Patient-level | Blinded metrologist |

DAS28 remission: TTT: 45% Control: 33% |

| Goekoop-Ruiterman, 2007 (BeST) (6) | N = 508; 20 rheumatology departments in the Netherlands | DAS44 (ESR) <2.4 (low disease activity) at year 2 | Yes; 12 weeks | 24 | Patient-level | Blinded metrologist |

Low disease activity: Initial combo with IFX: 40% Initial monotherapy: 22% |

Abbreviations: UK, United Kingdom; DAS, Disease Activity Score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; PGA, physician global assessment; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; IFX, infliximab; ULN, upper limit of normal

ACR remission criteria 1981

The treatment targets varied across trials, and the rates of attaining the targets in the intervention arms ranged from 31–82%. The intervention arms’ rates of reaching target were enhanced compared to the control arms’ in all but one study. The safety of TTT was comparable to the non-TTT arms with no greater rate of withdrawal due to adverse events. Several noted reduced progression in radiographic measures, but not all. Almost no information is available regarding the cost of a TTT strategy.(11)

Data on the prognostic importance of consistent control of disease activity gave birth to the TTT strategy. Achieving optimal outcomes and aiming for targets using treatment strategies with maximum benefit and minimal harms was the biggest motivation for developing recommendations for treatment of RA.(12) A recent international task force issued recommendations about TTT. While these recommendations are not uniformly accepted, several aspects of these TTT recommendations and principles are important to highlight (see Table 2). Remission is specified as the primary target, but the recommendations note that low disease activity may be an appropriate alternative target. The ACR RA treatment guidelines also point out the importance of these treatment goals.(13) It is further noted that the choice of the disease activity measure and target may be influenced by comorbidities and drug toxicities, and that patients must be appropriately informed about the treatment target. Furthermore, the TTT recommendations embed several important principles, including that RA treatment should be based on a model of shared decision making. They also appropriately note that many aspects of TTT are based on limited evidence.

Table 2.

Selected EULAR Recommendations and Principles of Treat to Target

Recommendations

|

Principles

|

Adapted from Reference (12).

Thus, the recommendations are both subtle and complex, requiring on the one hand that providers elicit patient’s treatment goals and preferences, and on the other hand that providers pursue a standardized treatment algorithm with an objective treatment target. While the algorithm will result in treatment that is no more aggressive than is typical for most patients and providers, some patients will experience an escalation in treatment beyond what would be typically prescribed.

II. Treat to Target Outside of Rheumatology

Treat to target has become a popular concept in the medical management of several common chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. In its early formulation, TTT was used in the care of diabetes mellitus to design trials that focused on a HbA1c target, as opposed to specific treatment algorithms or combinations.(14) The impressive reductions in long-term diabetes-related complications and overall mortality seen in the DCCT (Type I diabetes) and UKPDS (Type 2 diabetes) studies solidified consensus around threshold target-based therapy.(15, 16) The concept spread rapidly to the hypertension and lipid arenas where similar studies were undertaken with explicit blood pressure and LDL goals, respectively. Strategy trials, employing a TTT approach, were undertaken and often utilized non-physician providers and explicit algorithms for medication use.(17, 18)

The substantial long-term outcomes data from trials focused on lowering LDL, blood pressure or HbA1c lay a strong foundation for TTT. For example, a large meta-analysis of 14 statin trials showed that reaching target LDL reduced mortality by 12%.(19) As a result of these data, the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel recommendations rest upon Level I evidence.(20) That said, in the context of a randomized controlled strategy trial, more aggressive treatment targets for HbA1c among diabetics with cardiovascular disease produced worse outcomes in the arm with a more aggressive target.(21)

The success of TTT in other chronic conditions serves as an important motivator to a TTT strategy in RA. RA is similar to these conditions in that all are chronic conditions with effective treatments, and combination therapy is frequently required to control the disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rheumatoid Arthritis Characteristics Compared with Other Chronic Conditions in Which Treat to Target is Accepted Paradigm

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Other chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) | |

|---|---|---|

| SIMILARITIES | ||

|

| ||

| 1. Chronic disease | Almost always | Almost always |

| 2. Outcome measures | Continuous scales, e.g., DAS, CDAI, RAPID | Continuous blood measures, e.g., blood glucose, blood pressure, lipid panel |

| 3. Treatment benefits | Effective but disease flares common | Effective but often requires changes in therapy |

| 4. Combination therapy | Very frequent | Frequent for diabetes and hypertension |

|

| ||

| DIFFERENCES | ||

|

| ||

| 1. Disease course | Symptomatic with “flares” | Often without symptoms; “flares” are not common |

| 2. Treatment safety | Relatively safe; requires substantial monitoring | Generally safe; little monitoring for most medications except subcutaneous insulin, which requires daily monitoring |

| 3. Evidence for tight control | Relatively weak evidence for long-term benefits | Strong evidence for long-term benefits, some evidence of risks |

While the similarities between RA and these conditions in which TTT has been employed are important, several differences are also notable (see Table 3). First, RA is generally symptomatic and consequently patients can report their disease activity using validated self-report measures. In stark contrast, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are often, but not always, asymptomatic. The lack of symptoms can contribute to “clinical inertia” in which providers and patients become reluctant to change therapies despite imperfect disease control as evidenced by numerical targets.(22)

Second, treatments for RA require substantial disease monitoring for potential harms, including the risk of infections, heart failure or liver disease. While the absolute risk of these treatments is not likely different than many treatments for other chronic diseases, they are perceived by most patients (and many providers) as “dangerous” drugs because of their effects on the immune system and black box warnings related to cancer and infection. As well, most RA treatments have accompanying recommendations for laboratory monitoring which may add to the perception of risk. Such perceptions may create patient concerns about increasing doses, adding, or changing treatments.

Third, the evidence linking tight disease control with long-term improved outcomes is less robust for RA than it is for diabetes, hypertension or hyperlipidemia. Several studies suggest that tight long-term control in RA is more likely to help a patient achieve clinical remission and minimize radiographic damage than routine care, but efficacy ranges across patients and many still incur radiographic damage over time.(1–6) In contrast, the association between achieving target disease control in diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia and reduced long-term morbidity has been studied in many thousands of patients over several decades. It is noteworthy that along with beneficial effects, tight control of hyperglycemia and hypertension have also been associated with serious risks such as symptomatic hypoglycemia or hypotension, and even increased mortality in some multi-morbid sub-groups.(21)

III. Barriers to Treat to Target in Rheumatology

If we accept the benefits of a TTT paradigm in RA, many formidable challenges limit incorporating it into typical practice. First, it appears that many patients with RA do not even receive a DMARD. Population-based studies (not ones performed in rheumatology practice) demonstrate that 35–60% of patients with at least two diagnoses of RA do not have record of filling prescriptions for DMARDs.(23) It is likely that some of these patients do not have RA, have very mild disease, or have contra-indications to DMARDs. However, the sizable proportion of RA patients not receiving DMARDs suggests that widespread deployment of a TTT strategy will be challenging.

Second, few non-rheumatologists are comfortable managing DMARDs, and relatively few patients with RA have easy access to rheumatologists. A recent American College of Rheumatology workforce study demonstrated that 83% of urban areas in the US with populations between 10,000 and 50,000 have no rheumatologist; in those regions, the median distance to the nearest rheumatologist is 159 miles.(24) We also know that the strongest predictor of receiving DMARDs for a patients with RA is a visit with a rheumatologist.(25–27) Thus, without better access to rheumatologists, much of the RA population will likely not have a chance of being treated with a TTT strategy.

Third, even if patients can access a rheumatologist, many patients may not want to pursue a TTT strategy. As noted in Table 2, enlisting patients as partners in TTT is an important principle. However, it appears that a sizable portion of patients are reluctant to change treatments if they feel “ok” despite having active arthritis. In one study of more than 6000 subjects from the National Data Bank on Rheumatic Diseases, 77% indicated they were satisfied with their medications, yet 71% of these satisfied respondents had moderate or greater disease activity as assessed by their Patient Activity Scores and Health Assessment Questionnaire score. These observations demonstrate discordance between patients’ treatment preferences and their perceived pain and function.(28) Similar work from other researchers also demonstrates discordance between rheumatologists’ ratings of disease activity and their patients’ ratings.(29) Several possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that patients observe improvement in their disease state, even though they have not reached the desired target for disease activity. As well, patients may not be convinced that changing treatments will actually improve outcomes.

Fourth, TTT requires frequent visits and the use of structured RA disease activity measures, two potential impediments for rheumatologists with busy practices. While return visits for patients who have not reached target disease activity should be brief, frequent visits may be difficult for patients. Consistent use of structured disease activity measures (CDAI, SDAI, DAS28, RAPID) is required for a TTT strategy, but it is unclear that most rheumatology practices use them consistently.

Finally, since TTT requires rapid treatment escalation in the face of ongoing active disease, medications must be available without long delay. As any US-based provider knows, gaining approval for expensive treatments in RA is not quick and often burdensome. This barrier, plus expensive patient co-payments, is not likely to lessen as the pressure to reduce health care costs continues.

IV. Patient Perspectives on Treat to Target

One of the principles for TTT described by the International Task Force includes engaging the patient in a discussion about their goals for treatment. Relatively little has been written about RA patients’ understanding or attitudes regarding TTT. However, other chronic conditions where TTT has been used present some information regarding the patient’s perspectives.

It is clear despite well-documented campaigns to spread the provision of targeted diabetic therapy to achieve goal HbA1c levels, patient buy-in and adherence is still sub-optimal.(30) A host of patient-level barriers exist, including medication ease of dosing, cost, inconvenience, lack of disease symptoms, medication side effects, or disinterest in frequent monitoring necessary for glycemic control. Similar issues exist for both hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

While we do not yet have studies specifically focusing on patient’s attitudes towards TTT, several studies suggest that implementing and adhering to TTT strategies in clinical practice will be challenging. Findings from the National Data Bank on Rheumatic Diseases found that many patients are satisfied with their current medications despite having levels of disease activity that would warrant escalation of care according to TTT algorithms. Moreover, patients may be reluctant to change treatment regimens not only because of the fear of side effects associated with new medications, but because of a fear of losing control of their disease. Recent data suggests that high disease activity (as indicated by RAPID4 scores) is predictive of future escalation only in patients who also report that their illness has a significant physical and/or emotional impact on their quality of life.(31) Thus, patients who have adapted to their disease may not have changes on patient reported outcome measures and may be unlikely to be willing to escalate treatment, regardless of their disease activity score.(32) Data from TTT trials related to improvements in outcomes that patients can relate to, such as quality of life, would likely help patients understand the value of TTT.

TTT recommendations specify the importance of adhering to a shared decision making model. Given the structure inherent to the TTT approach, this model requires that patients are fully informed of the specific algorithms to be used and that they agree to increased burden of monitoring and likely escalations of care (even in some cases when they don’t feel that additional medications are required). Shared decision making may be easier to implement in TTT strategies using specific targets as opposed to those requiring the use of specific medications, since the former enables physicians to incorporate their patients’ treatment preferences. There has been some effort to make TTT recommendations more patient friendly;(33) this effort needs to continue.

It is important to consider the patient perspective in other diseases where TTT has been employed. Some literature suggests that while patient function may improve employing a TTT strategy, other data suggest that the burden of treatment (checking blood sugar, more needle sticks) can increase depression scores.(34, 35) In the setting of RA, the targets for treatment mix both objective scores (joint counts and inflammatory markers) with the patient experience (patient global). Thus, TTT in RA relies on treating towards a physiological target, but the patient must experience the target as a steppingstone to enhanced quality of life. Patients must be educated adequately to fully endorse the target in a TTT approach.

V. Conclusion

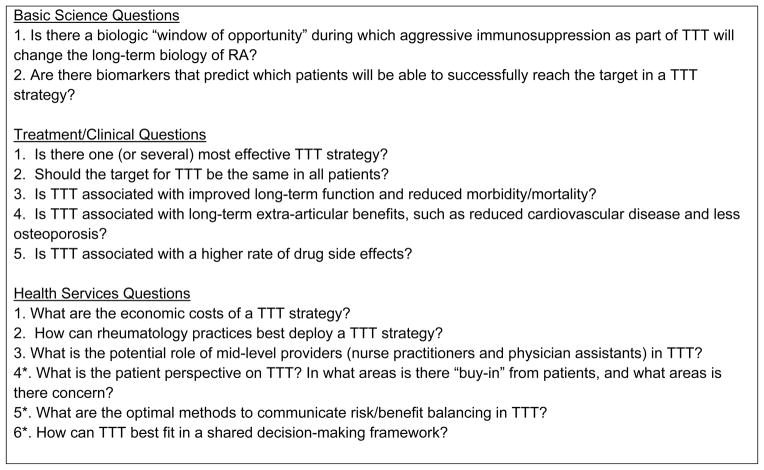

In conclusion, TTT in RA faces many challenges limiting its widespread acceptance. Some of these challenges are scientific due to a relatively sparse evidence-base. We have outlined some of the major questions facing TTT (see Figure 1). These can be fit into several categories of research: biologic, clinical, and health services. These topics may serve the rheumatology community well as areas for research proposals.

Figure 1.

Research Agenda for Treat to Target in Rheumatoid Arthritis

* These questions might be considered “patient-centered.”

Other barriers include potential conceptual mis-match: patients know how their arthritis affects their body and what they want from their treatments; their goals may not align with an objective target of low disease activity or remission. Further, some patients may be too fearful of the potential risks of aggressive therapy to engage in TTT. Moreover, access to rheumatic disease expertise limits the use of DMARDs in the US and certainly will limit dissemination of TTT. We believe that there is a continued need for testing and refining many of the concepts underpinning TTT in RA. We look forward to a robust research effort in response to the important potential posed by TTT. Clearly, TTT in RA holds promise with substantial evidence. However, many aspects of TTT need more data to push it from a hypothesis to a fully proven treatment strategy.

Acknowledgments

Funding for paper: NIAMS P60 AR477882

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts: Dr. Solomon receives salary support from research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Amgen, Lilly, and CORRONA. He serves in unpaid roles on trials funding by Pfizer, Novartis, Lilly and Bristol Myers Squibb. He receives royalties from UpToDate.

Contributor Information

Daniel H. Solomon, Email: dsolomon@partners.org.

Asaf Bitton, Email: abitton@partners.org.

Jeffrey N. Katz, Email: jnkatz@partners.org.

Helga Radner, Email: hradner@partners.org.

Erika Brown, Email: ebrown31@partners.org.

Liana Fraenkel, Email: liana.fraenkel@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, McMahon AD, Lock P, Vallance R, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9430):263–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ, Heurkens AH, Schenk Y, ter Borg EJ, et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(11):1443–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fransen J, Moens HB, Speyer I, van Riel PL. Effectiveness of systematic monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in daily practice: a multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(9):1294–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Nissila M, Kautiainen H, Ilonen J, et al. Delay to institution of therapy and induction of remission using single-drug or combination-disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(4):894–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders SA, Capell HA, Stirling A, Vallance R, Kincaid W, McMahon AD, et al. Triple therapy in early active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, single-blind, controlled trial comparing step-up and parallel treatment strategies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1310–7. doi: 10.1002/art.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(6):406–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symmons D, Tricker K, Roberts C, Davies L, Dawes P, Scott DL. The British Rheumatoid Outcome Study Group (BROSG) randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of aggressive versus symptomatic therapy in established rheumatoid arthritis. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(34):iii–iv. ix–x, 1–78. doi: 10.3310/hta9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, et al. Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year radiographic and clinical outcomes [see comment] Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2002;46(6):1443–50. doi: 10.1002/art.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;30:1586–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Tuyl LH, Lems WF, Voskuyl AE, Kerstens PJ, Garnero P, Dijkmans BA, et al. Tight control and intensified COBRA combination treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: 90% remission in a pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1574–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoels M, Wong J, Scott DL, Zink A, Richards P, Landewe R, et al. Economic aspects of treatment options in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):995–1003. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(4):631–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(5):625–39. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garber AJ. Treat-to-target trials: uses, interpretation and review of concepts. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1111/dom.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2643–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 13: Relative efficacy of randomly allocated diet, sulphonylurea, insulin, or metformin in patients with newly diagnosed non-insulin dependent diabetes followed for three years. Bmj. 1995;310(6972):83–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson SC, Jones WN, Evanko TM. Dosage of beta-adrenergic blockers after myocardial infarction. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(23):2471–4. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.23.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New JP, Mason JM, Freemantle N, Teasdale S, Wong LM, Bruce NJ, et al. Specialist nurse-led intervention to treat and control hypertension and hyperlipidemia in diabetes (SPLINT): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2250–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110(2):227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Buse JB, Goff DC, Jr, et al. Long-term effects of intensive glucose lowering on cardiovascular outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):818–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle JP, El-Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmajuk G, Trivedi AN, Solomon DH, Yelin E, Trupin L, Chakravarty EF, et al. Receipt of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in medicare managed care plans. Jama. 2011;305(5):480–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgerald J. Distribution of US Adult Rheumatologists. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmajuk G, Schneeweiss S, Katz JN, Weinblatt ME, Setoguchi S, Avorn J, et al. Treatment of older adult patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: improved but not optimal. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):928–34. doi: 10.1002/art.22890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh DP, Esdaile JM. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(2):241–8. doi: 10.1002/art.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM, Thorne JC, Cividino A, Pope J, et al. Quality care in seniors with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a Canadian perspective. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;63(1):53–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe F, Michaud K. Resistance of rheumatoid arthritis patients to changing therapy: discordance between disease activity and patients’ treatment choices. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(7):2135–42. doi: 10.1002/art.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barton JL, Imboden J, Graf J, Glidden D, Yelin EH, Schillinger D. Patient-physician discordance in assessments of global disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(6):857–64. doi: 10.1002/acr.20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett AH. Treating to goal: challenges of current management. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151 (Suppl 2):T3–7. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151t003. discussion T29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraenkel L, Cunningham MACR. High disease activity may not be sufficient to escalate care. Arthritis Care & Res. 2013 doi: 10.1002/acr.22098. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis JR, Shan Y, Harrold L, Zhang J, Greenberg JD, Reed GW. Patient Perspectives on Achieving Treat-to-Target Goals: A Critical Examination of Patient-Reported Outcomes. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65(10):1707–12. doi: 10.1002/acr.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Wit MP, Smolen JS, Gossec L, van der Heijde DM. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: the patient version of the international recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):891–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.146662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Kane MJ, Bunting B, Copeland M, Coates VE. Efficacy of self monitoring of blood glucose in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (ESMON study): randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;336(7654):1174–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39534.571644.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bitton A. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose: Depressingly Not Helpful in the Newly Diagnosed. J Clin Outcomes Management. 2008;15(7):318–319. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, Nissila M, Kautiainen H, Korpela M, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. FIN-RACo trial group. Lancet. 1999;353(9164):1568–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]