Abstract

Various polymorphisms in cytokine genes have recently been investigated as candidate risk factors in allogeneic hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). We retrospectively analyzed specific polymorphisms in genes for interleukin (IL)-10, IL-6, tumor-necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) in a pediatric cohort of 57 histocompatibility leucocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling myeloablative transplants. Both recipient and donor genotypes were tested for association with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) by statistical methods including Cox regression analysis. We found a significant association between the IL-10 promoter haplotype polymorphisms at positions -1082, -819 and -592 with the occurrence of severe (grades III–IV) acute GVHD (aGVHD). Recipients with the haplotype GCC had a statistically significant decreased risk of severe aGVHD (hazard risk (HR)=0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.06–0.67) in comparison with patients with other IL-10 haplotypes (P=0.008). Transplant-related mortality at 1 year was significantly lower in recipients with this haplotype (HR=0.17, 95% CI: 0.012–0.320) versus other IL-10 haplotypes (P=0.03), whereas overall survival was not influenced by IL-10 haplotype polymorphisms. In multivariate analysis, the presence of the IL-10 GCC haplotype was found as the only variable associated with a statistically significant decreased hazard of severe aGVHD development (P=0.02, HR=0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.78). These results suggest that pediatric patients possessing the IL-10 GCC haplotype may be protected from the occurrence of severe aGVHD in the setting of matched sibling HSCT.

Keywords: aGVHD, cytokine gene polymorphisms

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality following allogeneic hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) in both adults and children, even in recipients with a histocompatibility leucocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling donor. Despite the complete identity of the HLA genomic region of the recipient with the matched sibling donor, clinically significant acute GVHD (aGVHD; grades II–IV) occurs in approximately 20–40% of cases.1 It is well known that non-major HLA genetic differences between recipient and donor determine the occurrence and severity of GVHD in the matched sibling setting. These differences include minor histocompatibility antigens and non-HLA functional gene polymorphisms.2, 3 Genetic polymorphisms in genes encoding for pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines may alter the amount of cytokine produced and/or the degree of receptor expression, thus modulating the immune response to infection and allo-recognition.4 Previous studies showed that pro-inflammatory cytokine (interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8 and tumor-necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)) secretion during conditioning is involved in the pathogenesis of many transplant-related complications including GVHD, infection and veno-occlusive disease of the liver.5 In the last decade several groups showed the predictive value of certain polymorphisms at genes encoding for pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines for transplant outcome following both matched related and unrelated HSCT.6, 7, 8 However, published data have been inconsistent, probably reflecting the heterogeneity of the transplant cohorts regarding age of recipient, disease status, type of donor, source of stem cells, etc. In addition, most of the published studies have been undertaken in adult recipient–donor pairs and very few in children.9, 10 In the present study, we evaluated the impact of TNF-α, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), IL-6 and IL-10 gene polymorphisms on GVHD incidence and severity, transplant-related mortality (TRM) and overall survival (OS) in a cohort of 57 pediatric patients after myeloablative matched sibling HSCT.

Materials and methods

Characteristics of the patients and their donors

The entire study population consisted of 57 patients who underwent HSCT from HLA-matched sibling donors from January 1997 to December 2002 at the Aghia Sophia Children's Hospital (Athens, Greece). The country of origin for 55/57 patient/donor pairs was Greece, while the remaining two pairs were from Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively. The median recipient and donor ages were 9.6 (range: 0.4–17) and 13 (range: 3–17.5) years, respectively. All patients received myeloablative conditioning and a non-T cell-depleted graft. GVHD prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine in combination with methotrexate. Acute and chronic GVHD (cGVHD) were diagnosed and graded according to standard criteria.11 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation was monitored either by expression of the pp65 antigen or by quantitative PCR on a weekly basis until day +100. According to an established on-site protocol the detection of virus prior to engraftment led to preemptive treatment with intravenous foscarnet or else with gancyclovir with a minimum of 2 weeks of induction therapy. Blood cultures were performed to identify the etiology of bacterial and fungal infections. Specimens were submitted for microbial and fungal cultures according to standard methods. Empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was started when patients became febrile, and antifungal therapy was added in the presence of either clinical evidence of fungal infection or fever persisting after 5 days of antibiotic therapy. The study was approved by the local scientific committee and institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from the parents and from all patients and donors older than 12 years. Detailed characteristics of HSCT patient/donor pairs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the HSCT patient/donor pairs and transplant outcome.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 57 |

| Male | 32 |

| Female | 25 |

| Age (years) | 9.6 (range: 0.4–17) |

| Patient (median, range) | |

| Donor (median, range) | 13 (range: 3–17.5) |

| Female donor to male patient | 18 |

| Diagnosis | 24 |

| β-thalassemia | 18 |

| ALL | 6 |

| Myeloid malignancies | 4 |

| Immunodeficiencies | 5 |

| Aplastic syndromes | 7 |

| Conditioning regimen | 50 |

| TBI-based | |

| Non-TBISource of stem cells | |

| BM | 54 |

| PBSC | 3 |

| aGVHD | |

| Grades 0–I | 30 |

| Grades II–IV | 27 |

| Grades III–IV | 12 |

| Survival status | |

| Alive/dead | 41/16 |

Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow; HSCT, Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; TBI, total body irradiation.

Cytokine gene polymorphism analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from donors and patients before transplantation using minicolumn DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Cytokine genotypes were determined by polymerase chain reaction sequence-specific primer methodology with the Cytokine Genotyping Tray Kit (One Lambda Inc., Canoga Park, CA, USA). The tray provides sequence-specific oligonucleotide primers for the amplification of selected cytokine alleles including TNF-α (-308 G/A), IL-10 (-1082 G/A, -819 T/C and -592 A/C), IL-6 (-174 G/C) and IFN-γ (+874 A/T) and of human β-globin gene as an internal control of the genomic DNA preparation. All amplifications were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. PCR was performed with a MJ Research PTC-200 Thermocycler and the PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by ultraviolet transillumination.

Statistical analysis

The endpoint of this retrospective study was to analyse the influence of patient or donor cytokine-specific gene polymorphisms (CGPs) on GVHD incidence and severity, CMV and fungal infections incidence, TRM and OS in pediatric patients undergoing HLA-identical sibling HSCT. OS was defined as the time from the stem cell infusion to death from any cause, or last follow-up. TRM at 1 year was defined as death from any cause not associated with the original disease during the first year after hematopoietic stem cell infusion. Time-to-GVHD was considered as the time from the day of stem cell infusion to the onset of GVHD or death from any cause. Event-free patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. Time-to-event estimations were made according to the Kaplan–Meier method. Death due to relapse is a competing risk to TRM, while death from any cause is a competing risk to acute GVHD. Competing risk was taken into consideration when estimating the cumulative incidence rates of TRM and GVHD. NCSS software was used for estimation of cumulative incidence rates in the presence of competing risk. Univariate analysis of CGPs was made according to the log-rank test, separately for aGVHD grades II–IV, GVHD grades III–IV, cGVHD, OS and TRM. The variables CGPs, donor's and recipient's age (above versus below the median), disease type (malignant disorder versus not), female donor to male recipient, source of stem cells (bone marrow versus peripheral blood stem cells), total body irradiation and antithymocyte globulin each as part of the conditioning were analyzed as risk factors for aGVHD, severe aGVHD, cGVHD, TRM and OS using a stepwise proportional hazards Cox regression model. In addition to these factors, aGVHD was included as a covariate in the multivariate analysis for the endpoints TRM, OS and cGVHD. Only factors with P<0.1 in univariate analysis were retained in the multivariate model. Hazard risk (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from the multivariate analyses after adjustment for significant covariates in the model. Any variable associated a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Transplant outcome

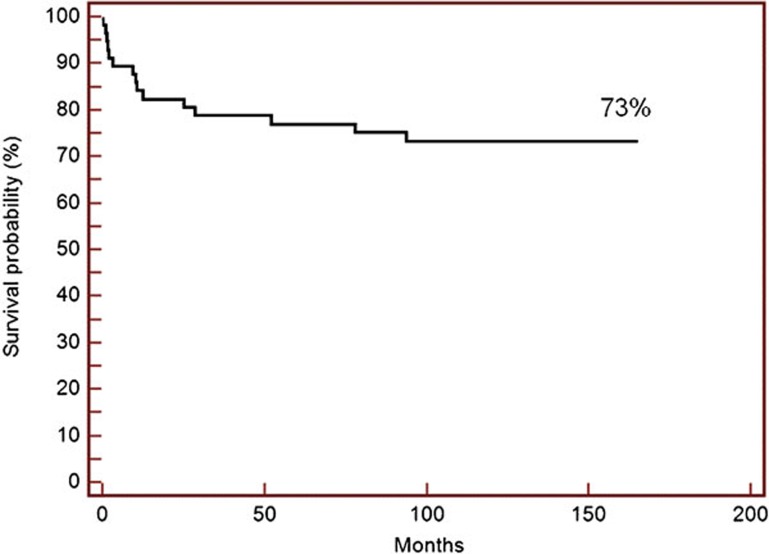

With a median follow-up of 105 months (range: 1–165 months), 16 out of 57 patients died, resulting in a 10-year OS rate of 73 % (Figure 1). Twenty-seven and 12 out of 57 patients developed aGVHD grades II–IV and III–IV, respectively. Median time to aGVHD onset was 24 days (range: 12–42 days) post-transplantation. The cumulative incidence of acute GVHD, grades II–IV and grades III–IV were 47.3% (95% CI: 36%–62.3%) and 21.1% (95% CI: 12.7–34.8%), respectively. Chronic GVHD occurred in 10 out of 50 patients who survived more than 100 days with a cumulative incidence of 19.3% (95% CI: 11.3–32.8%).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve shows the probability of overall survival for the entire cohort.

Twenty-four patients (45.5% 95% CI: 32–58%) developed at least one episode of CMV-positive antigenemia during the first 6 months after allo-HSCT, while four patients developed a documented fungal infection during the first 12 months post-transplantation (9% 95% CI: 0–12%).

Eight patients died due to causes unrelated to underlying disease, whereas another eight patients died due to progression of their primary disease. The cumulative incidence of TRM was 14.1% (95% CI: 7.4–26.8%).

Cytokine gene polymorphisms in donors and recipients

The distribution of cytokine genotype polymorphisms in donors and recipients of HSCT is shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the distribution of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between donors and recipients. Observed genotype frequencies for investigated SNPs were similar to those reported from other European centers/populations12 and with the data listed in SNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez) for European populations.

Table 2. Distribution of cytokine polymorphisms in recipients and donors of HSCT.

| Gene | SNP position | Genotype | Recipient (%) | Donor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | −308 | G/G | 75.4 | 74.5 |

| IFN-γ | +874 | G/A | 24.6 | 25.5 |

| IL-6 | −174 | A/A | 0 | 0 |

| IL-10 | −1082, −819, −592 | T/T | 17.6 | 13.7 |

| Τ/α | 56.1 | 56.9 | ||

| A/A | 26.3 | 29.4 | ||

| G/G | 43.8 | 56.9 | ||

| G/C | 47.4 | 35.3 | ||

| C/C | 8.8 | 7.8 | ||

| GCC/GCC | 15.8 | 17.6 | ||

| GCC/ACC | 21.1 | 15.7 | ||

| GCC/ATA | 22.8 | 21.6 | ||

| ACC/ACC | 14.0 | 21.6 | ||

| ACC/ATA | 17.5 | 15.7 | ||

| ATA/ATA | 8.8 | 7.8 |

Abbreviations: HSCT, Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation; IFN, interferon; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; TNF, tumor-necrosis factor.

Association between recipient and donor CGPs with the incidence and severity of GVHD

In neither donor nor recipient individual IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ polymorphic loci were associated with the incidence and/or severity of aGVHD (data not shown). However, IL-10 haplotype analysis revealed a significant association between the presence of the GCC haplotype and the incidence of severe aGVHD (grades III–IV). Recipients with the haplotype GCC had a statistically significant decreased risk of severe aGVHD (HR=0.20, 95% CI: 0.06–0.67) in comparison with patients with other IL-10 haplotypes (P=0.008) (Figure 2). The presence of the GCC IL-10 haplotype in the recipient as well as other variables known to contribute to the development of aGVHD (mentioned in the section on ‘Materials and methods') was inserted into a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model. In multivariate analysis, the presence of the IL-10 GCC haplotype was found as the only variable associated with a statistically significant decreased hazard of severe aGVHD development (P=0.020, HR=0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.78). No significant association was found between recipient and donor CGPs with the incidence and or severity of cGVHD (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Severe aGVHD (grades III–IV) in relation to the presence or absence of the IL-10 GCC haplotype in the recipients. Recipients with the IL-10 GCC haplotype had decreased risk to develop aGVHD grades III–IV compared to recipients without it (P=0.008). aGVHD, acute graft-versus-host disease.

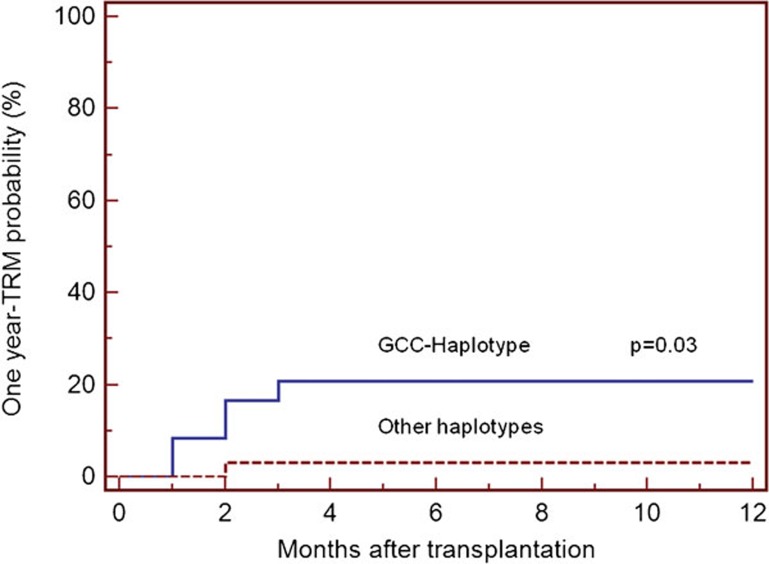

Association between recipient and donor CGPs with TRM, OS and infections

Statistical analysis did not reveal any significant effect of single CGPs (donor or recipient) on TRM, OS and CMV or fungal infections (data not shown). In univariate analysis, the absence of GCC haplotype in the recipient, as well as the development of severe aGVHD, was associated with increased risk for 1-year TRM (P=0.03, HR=6.21, 95% CI: 1.20–32.38) in comparison with patients with other IL-10 haplotypes (Figure 3). However, this association observed in univariate analysis was not apparent at a significant level in multivariate Cox regression model, where development of severe aGVHD (grades III–IV) was the only variable associated with a statistically significant increased risk for TRM (P=0.001, HR=12.7, 95% CI: 2.6–63). Ten patients carrying the GCC haplotype developed a positive CMV antigenemia as compared to the remaining 14 cases in which GCC was absent (P=0.71). Owing to the relatively low number of fungal infections encountered in this series, we were not able to detect any significant association between polymorphisms and the risk for development of fungal infections.

Figure 3.

TRM at 1 year after transplantation in relation to the presence or absence of the IL-10 GCC haplotype in the recipients. The probability of TRM at 1 year post-transplantation was significantly lower when the GCC haplotype was present in the recipient compared with when the haplotype was absent from the recipient (log-rank test: P=0.03). TRM, transplant-related mortality.

In multivariate analysis of factors assumed to have an influence on OS, allo-HSCT for a malignant disorder (P=0.007, HR=4.74, 95% CI: 1.52–14.81) and the development of severe aGVHD (P=0.013, HR=3.64, 95% CI: 1.30–10.16) were the only variables associated with a statistically significant increased hazard for death from any cause.

Discussion

CGPs resulting in high or low production of cytokines and/or inhibitors may significantly influence HSCT outcome. In the present study, we investigated both pediatric patients and donors for SNPs including those associated with genes transcribing high or low levels of cytokines. The prognostic importance of each of these variant alleles is conflicting in the literature, probably due to different demographics of the study population. In contrast to those studies, our cohort consisted of pediatric recipients, who received hematopoietic stem cells from their HLA-compatible siblings (pediatric donors) following myeloablative conditioning, and received cyclosporin-A plus methotrexate for GVHD prophylaxis. We did not find individual IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ polymorphic loci to be associated with GVHD, TRM or OS. However, IL-10 haplotype analysis, resulting from alleles at positions -1082, -819 and -592, revealed a significant association with the occurrence of severe aGVHD. Recipients without the GCC haplotype had a higher incidence of grades III–IV aGVHD and TRM at 1 year than GCC homozygotes or heterozygotes. However, after adjusting for other known risk factors for aGVHD and TRM, only the association of GCC haplotype with the occurrence of severe aGVHD remained statistically significant. This effect could be explained by the association of GCC haplotype with high IL-10 production, whereas ACC and ATA with low and intermediate production, respectively.13, 14 IL-10 is a well-known suppressive cytokine of T-cell proliferation; previous studies have shown an association between elevated levels of IL-10 and reduced risk of aGVHD.15, 16 The main source of IL-10 is monocytes which in hematopoetic stem cell transplant patients are of donor's origin and hence a donor's low producer genotype would be expected to increase the risk of GVHD. However, other non-hematopoietic cells may produce IL-10, including keratinocytes which originate from the recipient.17 Both the recipient and donor genotypes therefore may influence the occurrence of GVHD.18 Our study disclosed a protective effect of IL-10 GCC haplotype on the recipient side in developing severe aGVHD. The presence of this particular haplotype in donors did not correlate with GVHD or transplant outcome.

Other studies concerning IL-10 gene polymorphisms have shown conflicting results: some suggesting that a genotype relative to low production of IL-10 correlates with an increased risk of aGVHD19, 20 and others outlining an association between high producer genotype and acute or chronic GVHD.7 In a large cohort of HLA-matched sibling transplants, the presence of the IL-10 ATA/ACC genotype in the recipient has been associated with a moderate risk of GVHD and lower risk of death in remission,16 more severe GVHD occurring in groups without the IL-10 ATA haplotype. The study by Lin et al.16 assessed overall survival, allele frequency and genotypes at each IL-10 SNP and showed that the risk of death was the lowest in recipients who were homozygous for the -592A allele. In a recent study of a homogenous cohort of 228 HLA-identical sibling transplants for chronic myeloid leukemia, the absence of donor IL-10 ATA/ACC was associated with increased TRM and decreased OS.21

Regarding IL-10 production, it is still debatable whether the GCC haplotype is associated with higher or lower IL-10 production in comparison to the ATA haplotype. In another study of unrelated donor transplants, TRM was associated with the higher IL-10 producer GCC haplotype when present in the donor.7 However, the lower producer allele (IL-10-1082A) has also been associated with poor survival.22 Furthermore, it was shown that patients with ATA haplotypes required more prolonged immunosuppression due to increased incidence of cGVHD and were more susceptible to pulmonary aspergillosis, whereas the ACC haplotype reduced the risk of pulmonary aspergillosis ninefold.23, 24

Various factors alone or in combination may account for the differences in findings among previous studies, including sample size, study power, population heterogeneity (i.e. age, ethnicity, diagnosis and disease stage) and transplant characteristics.25 In some studies, related and unrelated donor transplantations were pooled and adjustments were not made for relevant clinical covariates. There has also been a lack of consistency in correlative analyses both in terms of the clinical endpoints (varying from aGVHD of any grade to significant grades II–IV to severe grade III-IV), and how genotypic information is used, especially in the construction of haplotypes.

In our study, the presence of the IL-10 GCC haplotype in the recipient had a preventive effect in the development of severe aGVHD. However, our data derived from a small cohort of pediatric patients and therefore do not allow for definitive conclusions regarding the impact of CGPs on HSCT outcome. Further confirmation is required in independent large multicenter cohorts before a combination of GVHD risk factors in pediatric HSCT could be considered, with IL-10 genotyping included in the analysis along with HLA matching, donor age and other known risk factors.

References

- Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host-disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AM, Middleton PG, Rocha V, Gluckman E, Holler E. Genetic polymorphisms predicting the outcome of bone marrow transplants. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:479–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AM, Charron D. Non-HLA immunogenetics in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz V, Yentur SP, Saruhan-Direskeneli G. IL-12 and IL-10 polymorphisms and their effects on cytokine production. Cytokine. 2005;30:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler E, Roncarolo MG, Hintermeier-Knabe R, Eissner G, Ertl B, Schulz U, et al. Prognostic significance of increased IL-10 production in patients prior to allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:237–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton PG, Taylor PR, Jackson G, Proctor SJ, Dickinson AM. Cytokine gene polymorphisms associating with severe acute graft-versus-host disease in HLA-identical sibling transplants. Blood. 1998;92:3943–3948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen LJ, DeFor TE, Bidwell JL, Davies SM, Bradley BA, Hows JM. Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha region haplotypes predict transplant-related mortality after unrelated donor stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;103:3599–3602. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambruzova Z, Mrazek F, Raida L, Jindra P, Vidan-Jeras B, Faber E, et al. Association of IL-6 and CCL2 gene polymorphisms with the outcome of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:227–235. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori H, Matsuzaki A, Suminoe A, Ihara K, Nagatoshi Y, Sakata N, et al. Polymorphisms of growth factor-beta 1 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 type II receptor genes are associated with acute graft-versus-host disease in children with HLA-matched sibling bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:665–671. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal RY, Lin Y, Schultz KR, Ferrell RE, Kim Y, Fairfull L, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α gene polymorphisms are associated with severity of acute graft-versus-host disease following matched unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation in children: A pediatric blood and marrow transplant consortium study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:927–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HLA-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18:295–304. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubistova Z, Mrazek F, Tudos Z, Kriegova E, Ambruzova Z, Mytilineos J, et al. Distribution of 22 cytokine gene polymorphisms in the healthy Czech population. Int J Immunogenet. 2006;33:261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2006.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DM, Williams DM, Sankaran D, Lazarus M, Sinnott PG, Hutchinson IV. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene promoter. Eur J Immunogenet. 1997;24:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.1997.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurreeman FA, Schonkeren JJ, Heijmans BT, Toes RE, Huizinga TW. Transcription of the IL10 gene reveals allele-specific regulation at the mRNA level. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentainer JE, Lieber SR, Persoli LB, Vigorito AC, Aranha FJ, de Brito Eid KA, et al. Serum cytokine levels and acute graft-versus-host disease after HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Storer B, Martin PJ, Tseng LH, Cooley T, Chen PJ, et al. Relation of an interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism to graft-versus-host disease and survival after hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2201–2210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akdis CA, Blaser K. Mechanisms of interleukin-10-mediated immune suppression. Immunology. 2001;103:131–136. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socié G, Loiseau P, Tamouza R, Janin A, Bousson M, Gluckman E, et al. Both genetic and clinical factors predict the development of graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;72:699–705. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavet J, Middleton PG, Segall M, Noreen H, Davies SM, Dickinson AM. Recipient tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms associate with early mortality and acute graft-versus-host disease severity in HLA matched sibling bone marrow transplants. Blood. 1999;98:3941–3946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto FE, Dall'Omo AM, Mazolla GA, Rendine S, Berrino M, Bertola B, et al. Role of non-HLA genetic polymorphisms in graft-versus-host disease after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Immunogenet. 2006;33:375–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AM, Pearce KF, Norden J, O'Brien SG, Holler E, Bickeboeller H, et al. Impact of genomic risk factors on outcome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Haematologica. 2010;95:922–927. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens F, Passweg J, Gratwohl A, Chalandon Y, Helg C, Chapuis B, et al. Association of TNFd and IL-10 polymorphisms with mortality in unrelated hematopoietic transplantation. Transplantation. 2006;81:1261–1267. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000208591.70229.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Lee NY, Sohn SK, Baek JH, Kim JG, Suh JS, et al. IL-10 promoter gene polymorphism associated with the occurrence of chronic GVHD and its clinical course during systemic immunosuppressive treatment for chronic GVHD after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79:1615–1622. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000159792.04757.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo KW, Kim DH, Sohn SK, Lee NY, Chang HH, Kim SW, et al. Protective role of interleukin-10 promoter gene polymorphism in the pathogenesis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia J, Ioannidis JP, Thakkinstian A, McEvoy M, Scott RJ, Minelli C, et al. How to use an article about genetic association, A: Background concepts. JAMA. 2009;301:74–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]