Abstract

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) have been shown to interact with antigen-presenting cells (APCs), especially dendritic cells (DCs). HSPs act as potent adjuvants, inducing a Th1 response, as well as antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) via cross-presentation. Our previous work has demonstrated that Hsp70-like protein 1 (Hsp70L1), a new member of the Hsp70 subfamily, can act as a powerful Th1 adjuvant in a DC-based vaccine. Here we report the efficient induction of tumor antigen-specific T cell immune response by DCs pulsed with recombinant fusion protein of Hsp70L1 and Her2341–456, the latter of which is a fragment of Her2/neu (Her2) containing E75 (a HLA-A2 restricted CTL epitope). The fusion protein Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 promotes the maturation of DCs and activates them to produce cytokines, such as IL-12 and TNF-α, and chemokines, such as MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES. Taken together, these results indicate that the adjuvant activity of Hsp70L1 is maintained in the fusion protein. Her2-specific HLA-A2.1-restricted CD8+ CTLs can be generated efficiently either from the Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) of healthy donors or from the splenocytes of immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice by in vitro stimulation or immunization with DCs pulsed with the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein. This results in more potent target cell killing in an antigen-specific and HLA-A2.1-restricted manner. Adoptive transfer of splenocytes from transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs can markedly inhibit tumor growth and prolong the survival of nude mice with Her2+/HLA-A2.1+ human carcinomas. These results suggest that Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs could be a new therapeutic vaccine for patients with Her2+ cancer.

Keywords: CTL, dendritic cell, heat shock protein, Her2/neu, immunotherapy

Introduction

The Th1 cellular immune response is crucial for anti-tumor and anti-microbial immunity. The administration of potent immunomodulatory adjuvants that are capable of inducing Th1 polarization is important in vaccination strategies. Heat shock proteins (HSPs), which can potently stimulate a Th1-polarized response, are prominent among these adjuvants.1, 2 HSPs have been shown to enhance the induction of antigen- and peptide-specific cellular immunity by binding to the antigen or peptide, causing the complex to be taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and efficiently presented on major histocompatibility complex-I (MHC-I) molecules. This activity can especially be seen in dendritic cells (DCs).1, 2, 3, 4 HSPs in these complexes, which consist of either fusion proteins complexed with antigen or peptide isolated from the tumor cells or generated artificially through covalent linkage, can interact with DCs in a receptor-mediated manner and increase MHC-II expression as well as cytokine and chemokine secretion by DCs. This interaction leads to the maturation of DCs and to their subsequent migration to draining lymph nodes, where they present antigens to T cells and initiate T-cell responses, particularly antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Therefore, the use of HSP preparations as adjuvants, especially in DC vaccination strategies, has attracted recent attention in immunotherapy for cancer and infectious diseases.

Hsp70-like protein 1 (Hsp70L1), which is a member of the Hsp70 subfamily previously identified in our previous study,7 has the ability to induce DC maturation and activation. Moreover, it has shown potential as a new Th1 adjuvant for use in peptide and fusion-protein immunizations for cancer treatment.7, 8

Her2/neu (Her2), which is a member of the tumor-associated antigen (TAA) category, is a 185-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that belongs to the family of epidermal growth-factor receptors, which contain an extracellular domain and an intracellular domain with tyrosine-specific kinase activity.9 Her2 is overexpressed in approximately 35% of colorectal and primary renal cancers, 30% of lung adenocarcinomas, 25% of human primary breast cancers, 10% of ovarian cancers and gastric cancer, where it is correlated with the stage of cancer progression.10 The high level of expression of Her2 in tumors makes it an attractive TAA for targeting for immunotherapeutic purposes. As a target antigen, Her2 has been extensively evaluated in both murine and human models.11 Several immunogenic peptides derived from the Her2/neu protein that are capable of inducing peptide-specific CTLs have been reported.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 E75 (Her2369–377, KIFGSLAFL), a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2.1-restricted CTL epitope peptide found in Her2, is the most frequently studied Her2-derived peptide in both laboratory and clinical studies.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Here, we fused Hsp70L1 with Her2341–456, which is a fragment of Her2 that contains the Her2-E75 epitope, to create the recombinant fusion protein Hsp70L1–Her2341–456. We investigated whether this fusion protein could activate DCs and whether a Her2-specific cellular response could be induced efficiently both in vitro and in vivo by DCs pulsed with this fusion protein. We demonstrated that antigenic epitopes in Her2341–456, when fused with Hsp70L1, were presented more efficiently as a result of the unique adjuvant effect of Hsp70L1 on DCs, and this effect consequently led to a strong induction of Her2-specific CTLs that specifically recognized and killed Her2-expressing tumor cells. These observations suggested that DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 could represent a new therapeutic strategy for Her2-expressing cancers and further confirmed that Hsp70L1 is a potent vaccination adjuvant in cancer immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell lines

HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Nude mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All mice were 6- to 8-week-old females and were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. The T2 cell line (TAP-deficient, HLA-A2.1+), human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line SW620 (Her2+, HLA-A2.1+) and human breast adenocarcinoma cell line SK-BR-3 (Her2+, HLA-A2.1−) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured according to its instructions.

Proteins and peptides

The Her2341–456 cDNA sequence was synthesized and inserted into a pUC18 plasmid vector to obtain the plasmid pUC18–Her2341–456. The Her2341–456 sequence used for Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 was amplified by PCR using the pUC18–Her2341–456 plasmid and the forward primer M13R and the reverse primer HSP–Her2-F 5′-CTCTATTGAGATAGCATCTTGTTACGGTTTGGGTATG-3′. The coding sequence of Hsp70L1 was amplified by PCR using the pPIC9k-Hsp70L1 plasmid, which contains the Hsp70L1 cDNA sequence and was constructed by our lab using the forward primer α-factor 5′-TACTATTGCCAGCATTGCTGC-3′ and the reverse primer HSP–Her2-R 5′-CATACCCAAACCGTAACAAGATGCTATCTCAATAGAG-3′.

The Her2341–456 fragment was then ligated to the C-terminus of Hsp70L1 using PCR with the forward primer α-factor and the reverse primer M13R. The pPICZα–Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and pPICZα–Her2341–456 plasmids were obtained by inserting the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 cDNA sequence into a pPICZαA plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The recombinant expression vector for the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein and the Her2341–456 protein was constructed by inserting the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 coding sequence, which was double-enzyme digested from the pPICZα–HSP70L1–Her2341–456 or pPICZα–Her2341–456 plasmid, into a pPIC9k expression vector (Invitrogen). The recombinant pPIC9k–Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and the pPIC9k–Her2341–456 plasmid were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain DH5α [pREP4] for amplification. Sequencing confirmed that the pPIC9k–Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and pPIC9k–Her2341–456 transformants were linearized with SacI enzyme digestion before transfer into the competent GS115 Pichia by electroporation.

GS115 Pichia cells were prepared according to the manufacture's instructions. The electroporating pulse was performed at 2.0 kV, 25 µF and 200 Ω using an Electro Cell Manipulator 600 (BTX, San Diego, CA, USA). Follow-up procedures were performed according to the manual of Pichia Expression System. The supernatants from the protein-expressing Pichia cells were collected by centrifugation at 4 °C at 10 000 g for 10 min and were analyzed for Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 expression using sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were purified using phenyl-sepharose HP chromatography and SourceQ anion exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences China, Shanghai, China). The purified recombinant human Hsp70L1 protein (Hsp70L1) was obtained as described previously.7 The purity of the recombinant Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein (Hsp70L1–Her2341–456) and of the Her2341–456 protein was more than 95% as indicated by silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. LPS contamination was less than 0.1 EU/µg protein as determined with the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA).

Her2-E75 and CAP-1 (CEA605–613, YLSGANLNL, an HLA-A2.1-restricted CTL epitope derived from CEA) peptides were synthesized at GL Biochem, Ltd (Shanghai, China) and were determined to be >95% purity using reverse phase HPLC and the purity was confirmed using mass spectrometry.

Generation of human DCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from healthy donors by Ficoll/Hypaque (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) density gradient centrifugation. Human peripheral blood monocyte-derived DCs were generated as described previously.27

Cytokine and chemokine production assays

Human DCs were cultured for 5 days and adjusted to a final concentration of 3×105 cells/ml in 24-well plates, after which 7.5 µg/ml of either Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Hsp70L1, Her2341–456 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added. Supernatants from designated wells were harvested after 2, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h for quantification of cytokines, such as IL-12p70 and TNF-α and chemokines, including MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis

After 5 days of culture, human DCs were stimulated with 7.5 µg/ml Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 or Her2341–456 for 48 h. After this, the DCs were collected, washed with PBS and stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD80, anti-CD83, anti-CD86 or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-HLA-DR monoclonal antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for analysis using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Generation of human CTLs and isolation of CD8+ T cells

DCs cultured for 5 days were harvested, stimulated with 7.5 µg/ml Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 or Her2341–456 for 4 h and then washed twice in serum-free RPMI1640 medium. 2×106 PBLs and 2×105 protein-pulsed autologous DCs were cocultured in 1 ml RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in 24-well plates. The cells were restimulated with fresh protein-pulsed autologous DCs every 7 days either two or three times. On day 3 after the second stimulation, 20 IU/ml rhIL-2 (Sigma) was added. Half of the medium was removed every 3 days and replaced with fresh medium containing rhIL-2 (20 IU/ml, cells were and expanded as necessary. On day 7 after the final stimulation, cells were harvested, and CD8+ T lymphocytes were enriched by positive selection using immune beads (Miltenyi) following the manufacturer's recommended procedure, after which cytotoxicity was tested.

Vaccination of HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice

HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice are a well-established model for studying HLA-A2.1-restricted CTL epitopes and vaccine development.28 In this study, mouse bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) were generated from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice as previously described.29 On day 5, BMDCs were harvested, plated at a cell concentration of 2×106/ml, pulsed with 7.5 µg/ml Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 or Her2341–456 for 4 h and then washed. HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice were immunized subcutaneously three times at 1-week intervals with 1×106 protein-pulsed BMDCs per mouse. A control group received PBS-treated BMDCs.

Generation of CTLs in HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice

7 days after the last immunization as described above, spleens were isolated from the mice, and splenocytes were adjusted to a concentration of 2×107 cells/well in six-well plates. The splenocytes were then stimulated with 7.5 µg/ml Her2341–456 for 7 days in vitro. Then cells were harvested and CD8+ cells enriched as effector cells to test the cytotoxicity to target cells.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxicity assays were performed using a standard 4-h lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. T2 cells were pulsed with 10 µg/ml Her2-E75 or CAP-1 peptide for 1 hour at 37 °C. Peptide-pulsed or non-pulsed T2 cells and Her2+ or Her2− tumor cell lines were used as target cells, and were added to serial dilutions of effector cells isolated as described above in 96-well round-bottom plates at various E/T cell ratios (2.5∶1, 5∶1 and 10∶1 in human CTL assays; 10∶1, 25∶1 and 50∶1 in mice CTL assays). After 4 h at 37 °C, cytotoxicity was quantified by measurement of the cytosolic enzyme, LDH, in the culture supernatant using the Cyto Tox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Specific lysis for each E/T cell ratio is expressed as: specific lysis (%)=[(target experimental release)–(target spontaneous release)]/[(target maximum release)–(target spontaneous release)]×100%. Spontaneous LDH release in the absence of CTL was <10% of the maximal cellular release by detergent lysis.

Adoptive transfer of splenocytes from immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice to nude mice bearing Her2+ human carcinomas

Splenocytes from each group of immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice were stimulated with 7.5 µg/ml Her2341–456 for 7 days as described above. Nude mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2×106 SW620 tumor cells in the right flank area, and 3 days later injected intravenously with 1×108 stimulated splenocytes derived from immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice per mouse in 200 µl. This adoptive transfer was performed twice at 1-week intervals, and followed by intraperitoneal injection of 2000 IU IL-2 per mouse every 2 days. Control mice either received splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with PBS-treated DCs or were administered with IL-2 only.

Statistical analysis

The differences in the growth of SW620 tumors as measured by tumor diameters within each group were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. To compare mouse survival between treatment and control groups, the Kaplan–Meier statistical analysis test was performed. All other statistical analyses were based on Student's t-test.

Results

Enhanced maturation and activation of DCs treated with recombinant Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein

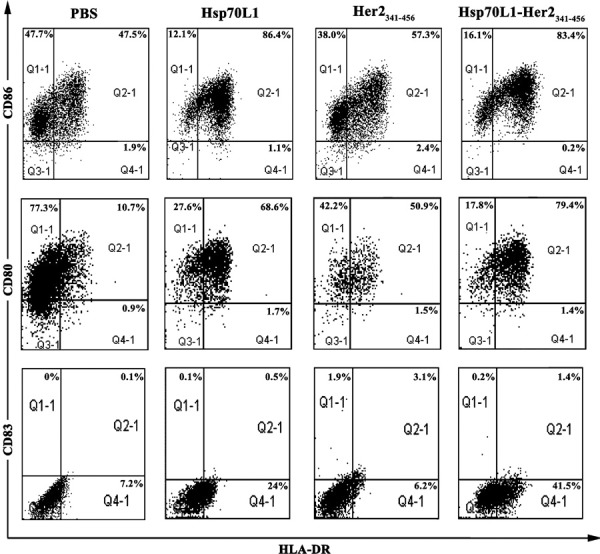

Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and Hsp70L1 both promoted upregulation of CD80, CD83 and CD86 expression on DCs, but Her2341–456 or PBS did not (Figure 1). We observed an increase in IL-12p70 and TNF-α secretion by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Hsp70L1-stimulated DCs, but not by Her2341–456- or PBS-treated DCs (P<0.05) (Figure 2). Interestingly, the production of IL-12p70 and TNF-α by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-stimulated DCs was higher than that by Hsp70L1-stimulated DCs (P<0.05). The secretion levels of IL-12p70 and TNF-α reached a peak after 48 hours of DC stimulation with either Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Hsp70L1. The observed cytokine profile suggested that DCs stimulated with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 could secrete high levels of Th1-type cytokines, such as IL-12p70, but DCs stimulated with Her2341–456 alone could not. Human DCs produced more MIP-1α, MIP-1β , and RANTES after stimulation with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 than after stimulation with Her2341–456 alone. As shown in Figure 2, Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and Hsp70L1 could both induce DCs to secrete MIP-1α, MIP-1β or RANTES more than Her2342–456. Maximum secretion occurred after 48 h of treatment. Secretion was not detected in supernatants from either Her2341–56- or PBS-treated DCs (P<0.01). Additionally, the levels of MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES production by DCs induced by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 were considerably higher than those treated with Hsp70L1, indicating that when fused with Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 induces greater amounts of chemokine production.

Figure 1.

Increased phenotypic maturation and activation of DCs by recombinant Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein stimulation. DCs were treated with 7.5 µg/ml Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 or PBS for 48 h and then collected for FACS analysis of HLA-DR, CD80, CD86 and CD83 expression. The representative schematic depicts flow cytometric analysis of a sample from PBS-treated DCs (first line), Her2341–456-stimulated DCs (second line), Hsp70L1-stimulated DCs (third line) and Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-stimulated DCs (fourth line). HLA-DR+ positive cells were gated at the Q2-1 and Q4-1 areas, CD80+, CD86+ and CD83+ positive cells gated at the Q1-1 and Q2-1 areas, and the double positive cells gated at the Q2-1 area. All positive cell populations were labeled with the percentage of total DCs. DC, dendritic cell; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSP, heat shock protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Figure 2.

Increased cytokine and chemokine secretion from DCs stimulated with the recombinant Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein. DCs cultured for 5 days were stimulated with 7.5 µg/ml Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Her2341–456, Hsp70L1 or PBS for 72 h. The levels of IL-12p70, TNF-α, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES present in the supernatants were measured by ELISA. Data are displayed as the mean cytokine or chemokine concentration (pg/ml)±s.e.m. For chemokine and cytokine production, * indicates a significant difference (P<0.05) between Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and Hsp70L1 stimulation, and ** indicates a significant difference (P<0.05) between Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and Her2341–456 stimulation. DC, dendritic cell; HSP, heat shock protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

These results indicated that Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, like Hsp70L1, could efficiently induce phenotypic and functional maturation of DCs and activate DCs to secret increased levels of Th1-associated cytokines as well as chemokines that could recruit various kinds of immune cells contributing to initiation of an immune response. Excitingly, Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 is more potent at inducing maturation and activation of DCs than Hsp70L1 alone. This result shows that that when Hsp70L1 is part of the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein, it can act as a Th1 adjuvant, and these effects are stronger than those induced by Hsp70L1 alone.

Efficient induction of Her2-specific CD8+ CTLs by human DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein

We co-incubated PBLs from healthy donors and autologous DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 to determine whether Her2-specific CTLs could be elicited more effectively by DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456. As shown in Figure 3, DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 induced the generation of Her2-specific CD8+ CTLs in cell populations from all donors in this study, and these CTLs displayed Her2-specific killing of SW620 cells (Her2+, HLA-A2.1+) and T2 cells pulsed with Her2-E75, but they failed to lyse SK-BR-3 cells (Her2+, HLA-A2.1−) and CAP-1-pulsed T2 cells (P<0.05). Lysis of non-pulsed T2 cells was not observed. The above results indicated that these CTLs were Her2-specific and HLA-A2.1-restricted. The cytotoxicity of CTLs induced by DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 against target cells was more potent than that of CTLs induced by DCs pulsed with Her2341–456 alone (P<0.05), further confirming the effectiveness of the adjuvant activity of Hsp70L1 in the fusion protein.

Figure 3.

In vitro induction of human Her2-specific CTL responses by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs. PBLs from healthy donors were stimulated with autologous DCs pre-pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 to assess the Her2-specific CTL responses by a standard 4-h lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. CD8+ CTLs purified from the PBLs stimulated with three rounds of DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 were used as effector cells (E), and SW620 cells (Her2+, HLA-A2.1+) and T2 cells pulsed with Her2-E75 were used as target cells (T). Control targets included SK-BR-3 cells (Her2+, HLA-A2.1−), irrelevant CAP-1 peptide pulsed or unpulsed T2 cells. Various E/T ratios were tested as indicated. Data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DC, dendritic cell; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSP, heat shock protein.

Together with the above data, our results reinforced the conclusion that the adjuvant effects of the Hsp70L1 component of the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein, induced superior DC maturation and activation, and antigen bound to Hsp70L1 could be presented highly efficiently to T cells and trigger a potent Her2-specific CD8+ T-cell response.

Efficient induction of Her2-specific CTLs in HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized by DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein

To assess whether DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 were able to induce a Her2-specific CD8+ T cell response in vivo, we immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice with syngeneic DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456, Her2341–456 or Hsp70L1, using PBS-treated DCs as a control. Splenocytes were isolated, stimulated and assayed for CTL cytotoxicity after three rounds of immunization in vivo. As shown in Figure 4, splenocytes from mice immunized with DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Her2341–456 induced lysis in SW620 and Her2-E75-pulsed T2 cells, but were unable to lyse SK-BR-3 or unpulsed T2 cells. In contrast, splenocytes from mice immunized with Hsp70L1-pulsed or PBS-treated DCs showed almost no cytotoxicity toward the target cells. Splenocytes from mice immunized with DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 showed more potent antigen-specific lysis ability toward SW620 and Her2-E75-pulsed T2 cells than those from mice immunized with DCs pulsed with Her2341–456 (P<0.05). These observations indicated that immunization with DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 could induce Her2-specific CTLs more efficiently in vivo and that DCs pulsed with only Hsp70L1 (without Her2) could not induce Her2-specific CTLs.

Figure 4.

Induction of Her2-specific Th1 responses and CTLs in HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs. Splenocytes from immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice were used to assess Her2-specific immune responses by a CTL assay. The splenocytes were stimulated with Her2341–456 and then used as effector cells (E), and SW620 cells (Her2+, HLA-A2.1+) cells and Her2-E75 peptide pulsed T2 cells were used as Her2-specific and HLA-A2.1-restricted targets (T), with SK-BR-3 and T2 cells as control targets. Various E/T ratios were tested as indicated. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; DC, dendritic cell; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSP, heat shock protein.

Potent anti-tumor effect of adoptive transfer of splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein

Nude mice were inoculated with SW620, a human Her2+/HLA-A2.1+ carcinoma cell line. After 3 days, they were injected intravenously with in vitro Her2341–456-stimulated splenocytes derived from immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice, and this was followed by intraperitoneal injections of 2000 IU IL-2 per mouse every 2 days. After three cycles of immunization, as shown in Figure 5, adoptive transfer of splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs was able to inhibit SW620 growth in nude mice. No significant tumor growth inhibition or survival improvement was observed in other groups. All mice in the control group developed palpable tumors 4 days after tumor cell inoculation, whereas tumor growth observed in nude mice injected with splenocytes from mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs was not apparent until 16 days after tumor cell injection. In this group, three of the eight mice remained tumor free, and 25% of the mice survived for longer than 90 days after SW620 tumor cell inoculation. In contrast, all mice in the control groups died between days 25 and 50 after tumor cell inoculation (Figure 6). Mice receiving a low dose of IL-2 alone showed no significant difference in tumor growth when compared to the control group receiving splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with PBS-treated DCs (data not shown). We did not observe any protection in tumor-bearing nude mice receiving splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1-pulsed DCs. These data demonstrate that the adoptive transfer of splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs more potently protected against Her2+/HLA-A2.1+ tumor cells than splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with DCs pulsed with Her2341–456 or Hsp70L1 alone, strongly suggesting that DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 could be an effective immunotherapeutic strategy for protection against Her2+/HLA-A2.1+ cancers.

Figure 5.

Suppression of tumor growth by adoptively transferred splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs. Athymic nude mice were injected s.c. with 2×106 SW620 cells. After 3 days, 1×108 Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 restimulated splenocytes derived from each group of immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice was transferred by i.v. injection in a volume of 0.2 ml. Additionally, mice received 2000 IU IL-2 i.p. in a volume of 0.5 ml every 2 days. The control groups received either IL-2 administration alone or no treatment. Following SW620 tumor inoculation, tumor growth was monitored by measuring the diameter of the tumor every 2 days and recorded as the average tumor diameter. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSP, heat shock protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. s.c., subcutaneous injection; i.v., intravenous injection; i.p., intraperitoneal injection.

Figure 6.

Prolonging survival of SW620 tumor-bearing mice receiving adoptively transferred splenocytes from HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice immunized with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs. Nude mice were injected s.c. with 2×106 SW620 cells. After 3 days, 1×108 Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-restimulated splenocytes derived from each group of immunized HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice was transferred by i.v. injection in a volume of 0.2 ml. Additionally, mice received 2000 IU IL-2 i.p. in a volume of 0.5 ml every 2 days. The control groups received either IL-2 administration alone or no treatment. The survival of mice receiving adoptive transfer of splenocytes after SW620 tumor inoculation was recorded. Each group contained eight mice. s.c., subcutaneous injection; i.v., intravenous injection; i.p., intraperitoneal injection. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSP, heat shock protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Discussion

CTLs play a key role in the treatment of cancer. In all of the healthy donors we tested, CTLs were induced by stimulation with DCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and were strongly capable of specifically lysing SW620 target cells and Her2-E75-pulsed T2 cells. Additionally, the lysis of target cells by CTLs induced using Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-stimulated DCs was significantly greater than that of CTLs generated by Her2341–456-stimulated DCs. These results indicated that antigenic epitopes in Her2341–456, in conjunction with the adjuvant activity of Hsp70L1, displayed increased immunogenicity and could be more efficiently processed and presented by DCs. More interestingly, CTLs induced by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-stimulated DCs showed greater cytotoxicity towards SW620 cells than Her2-E75-pulsed T2 cells. This result suggested that vaccines based on the Her2341–456 fragment might be immunogenic across more than one HLA type and suggests an active process of immuno-editing of Her2341–456 antigen by DCs. Although peptide based vaccines have the disadvantage of being presented by only one HLA type, polypeptides or proteins, such as Her2341–456, derived from specific antigens can be presented by multiple HLA types, which could expand the vaccine coverage of patient populations.

Maturation and activation of DCs is required for the upregulation of costimulatory molecules, the enhancement of APC function and the expression of chemokine receptors, all of which promote migration to T-cell regions within the lymph node.30 Vaccination strategies aimed at inducing immunity toward cancer or infectious diseases are strongly suggested to include the means to stimulate the maturation of the targeted DC. In this study, we found that Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 could enhance the expression of CD80, CD83, and CD86 on DCs and promote maturation of DCs, which is critical for their APC function.31 We observed a remarkable increase in IL-12p70 secretion by DCs stimulated with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 and Hsp70L1, but not by DCs treated with Her2341–456 or PBS (P<0.05). The high levels of IL-12p70 production stimulated by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 or Hsp70L1 suggest that initiation of a T-cell response is important in any vaccine approach that seeks to trigger a strong anti-tumor immune response. Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 also induced DCs to produce TNF-α, whose autocrine or paracrine secretion could stimulate DC maturation. Thus, unlike some DC-based vaccines, including protocols for maturing DCs by TNF-α or CD40 ligation,30 Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 may directly act on immature DCs and induce their phenotypic and functional maturation via the adjuvant activity of the Hsp70L1 portion. Moreover, in our study, MIP-1α, MIP-1β and RANTES secreted by Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-stimulated DCs were expected to exhibit strong chemoattractant effects on T cells, resulting in an improved immune response.

Her2 is a self-antigen with a tendency to be immunologically tolerated, which has led to the failure of several clinical immunotherapy trials.32 Over the past few years, monoclonal antibodies targeting Her2, such as trastuzumab (Herceptin), have been approved for the treatment of patients with Her2+ breast cancer. The significant limitation of this application is that drug resistance usually develops within 1 year from the beginning of the treatment, and a large number of patients fail to respond to treatment and relapse.33, 34 Moreover, a risk of cardiac toxicity from Herceptin, especially in patients previously treated with anthracyclines, has been observed, which has become a therapeutic obstacle.35, 36 DCs are now considered to be one of the best adjuvants for antitumor immunity.31 Owing to their unique abilities to take up, process, and present antigens and to their ability to activate specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, DCs are increasingly used as vector for vaccination, and the immunogenicity of antigens delivered by DCs has now been shown in clinical settings.31, 37, 38 The first tumor vaccine based on the usage of APCs was approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with advanced prostate cancer.39 The potential strength of a DC-based strategy for enhancing the immunogenicity of Her2 has been shown by the fact that Her2-expressing adenovirus transduced-DCs and Her2-E75 or other Her2-derived peptide-pulsed DC vaccines induce Her2 specific CTLs in patients with Her2+ tumors.40, 41, 42 In this study, the Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 pulsed DC vaccine induced a Her2-specific CTL response and anti-tumor effects both in vitro and in vivo. Eventually, the potent adjuvant activity of Hsp70L1 may further reduce the weak antigenicity of Her2, and should promote the induced CTLs to kill Her2+ tumor cells. Our observations demonstrated that this Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 fusion protein based DC vaccine was effective for Her2+ tumor treatment.

HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice expressing human HLA-A2.1 are a well-established model for studying human tumor-associated HLA-A2.1-restricted CTL epitopes and for preclinical vaccine studies. Using these transgenic mice overcomes the dual problem of human antigenic epitopes not binding to mouse MHC molecules and of mouse CD8+ T cells not interacting with the α3 domain of human MHC molecules.43 We investigated whether Her2-specific CTLs could be induced by immunization of HLA-A2.1/Kb transgenic mice with BMDCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456. We demonstrated that the CTLs from these mice were able to lyse SW620 target cells and Her2-E75-pulsed T2 cells, showing stronger antigen-specific cytotoxicity than those generated from mice immunized with Her2341–456 pulsed BMDCs. These results indicated the in vivo ability of BMDCs pulsed with Hsp70L1–Her2341–456 to induce Her2-specific CTLs.

It has been well established that the adjuvant effects of HSPs in vaccination models can initiate specific cellular immune responses against associated antigens. Therefore, vaccination strategies with HSP preparations have attracted increasing attention for the immunotherapy of cancers and infectious diseases. One vaccination approach using an autologous, tumor-derived Hsp (glycoprotein 96)-peptide complex (HSPPC-96; vitespen) to treat patients at a high risk of recurrence after resection of locally advanced renal cell carcinoma has been evaluated in a phase III clinical trial.44 As a new HSP member similar to its homologue Hsp70, Hsp70L1 has been shown to be a potent Th1 adjuvant, which could be utilized in future vaccine approaches. In our Hsp70L1–Her2341–456-pulsed DCs strategy, Hsp70L1 showed stronger adjuvant capabilities in the form of Hsp70L1–TAA fusion protein than Hsp70L1 alone, suggesting that Hsp70L1 could serve as an adjuvant in a fusion protein for vaccine application. Although here we examined only Her2 as an antigen, it is reasonable to predict that Hsp70L1 could be fused with a variety of other TAAs or other antigenic peptides, conferring powerful immune activating properties on these proteins. The application of Hsp70L1 in future immunotherapeutic vaccine strategies as a new and potent adjuvant of mammalian origin could be extended to a wider range of tumors, as well as infectious diseases such as hepatitis B virus, human papillomavirus and human immunodeficiency virus infection, eliciting and enhancing specific immune responses.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Major Program of the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology Development (QF, 06DZ19010), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (YFW, 2009AA02Z102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (YFW, 30872296) and the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (TWan, 2008ZX09101-043).

References

- Srivastava PK. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhassani A, Rafati S. Heat-shock proteins as powerful weapons in vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:1185–1199. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.8.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK. Interaction of heat shock proteins with peptides and antigen presenting cells: chaperoning of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto Y, Bharti A, Khaleque AA, Song B, Liu C, Apostolopoulos V, et al. Enhanced immunogenicity of heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes from dendritic cell–tumor fusion cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5946–5955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura Y, Peng P, Liu K, Daou M, Srivastava PK. Immunotherapy of tumors with autologous tumor derived heat shock protein preparations. Science. 1997;278:117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilla L, Patuzzo R, Rivoltini L, Maio M, Pennacchioli E, Lamaj E, et al. A phase II trial of vaccination with autologous, tumor-derived heat-shock protein peptide complexes gp96, in combination with GM-CSF and interferon-α in metastatic melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:958–968. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0084-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan T, Zhou X, Chen G, An H, Chen T, Zhang W, et al. Novel heat shock protein Hsp70L1 activates dendritic cells and acts as a Th1 polarizing adjuvant. Blood. 2004;103:1747–1754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Wan T, Zhou X, Wang B, Yang F, Li N, et al. Hsp70-like protein 1 fusion protein enhances induction of carcinoembryonic antigen-specific CD8+ CTL response by dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4947–4954. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard KI, Shepherd LE, O'Malley FP, Andrulis IL, Tu D, Bramwell VH, et al. HER2 and responsiveness of breast cancer to adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2103–2111. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhesy-Thind B, Pritchard KI, Messersmith H, O'Malley FP, Elavathil L, Trudeau M. HER2/neu in systemic therapy for women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:209–229. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9656-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanis CN, Sotiriadou NN, Gritzapis AD, Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Cacoullos NT, et al. Immunogenic HER-2/neu peptides as tumor vaccines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0692-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling R, Wei WZ, Herrmann F, Lindencrona JA, Choudhury A, Kono K, et al. Cellular immunity to the HER-2/neu protooncogene. Adv Cancer Res. 2002;85:101–144. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(02)85004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutsas IF, Gritzapis AD, Mahaira LG, Salagianni M, von Hofe E, Kallinteris NL, et al. Peptide vaccine given with a Toll-like receptor agonist is effective for the treatment and prevention of spontaneous breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1326–1334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima I, Tsai V, Southwood S, Takesako K, Sette A, Celis E. Identification of HLA-A3-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes from carcinoembryonic antigen and HER-2/neu by primary in vitro immunization with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:431–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritzapis AD, Voutsas IF, Lekka E, Tsavaris N, Missitzis I, Sotiropoulou P, et al. Identification of a novel immunogenic HLA-A*0201-binding epitope of HER-2/neu with potent antitumor properties. J Immunol. 2008;181:146–154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino E, Spadaro M, Iezzi M, Curcio C, Forni G, Musiani P, et al. Immunosurveillance of Erbb2 carcinogenesis in transgenic mice is concealed by a dominant regulatory T-cell self-tolerance. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7734–7740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritzapis AD, Mahaira LG, Perez SA, Cacoullos NT, Papamichail M, Baxevanis CN. Vaccination with human HER-2/neu435–443 CTL peptide induces effective antitumor immunity against HER-2/neu-expressing tumor cells in vivo. . Cancer Res. 2006;66:5452–5460. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxevanis CN. Induction of potent CD4+ T cell-mediated antitumor responses by a helper HER-2/neu peptide linked to the Ii-Key moiety of the invariant chain. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2031–2041. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossart P, Wirths S, Stuhler G, Reichardt VL, Kanz K, Brugger W. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:3102–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disis ML, Gooley TA, Rinn K, Davis D, Piepkorn M, Cheever MA, et al. Generation of T-cell immunity to the HER-2/neu protein after active immunization with HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2624–2632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disis ML, Grabstein KH, Sleath PR, Cheever MA. Generation of immunity to the HER-2/neu oncogenic protein in patients with breast and ovarian cancer using a peptide-based vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1289–1297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, SchiVman K, Cheever MA, Disis ML. Immunization of cancer patients with a HER-2/neu, HLA-A2 peptide, p369–377, results in short-lived peptide-specific immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1014–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono K, Takahashi A, Sugai H, Fujii H, Choudhury AR, Kiessling R, et al. Dendritic cells pulsed with HER-2/neu derived peptides can induce specific T-cell responses in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3394–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JL, Gillogly ME, Przepiorka D, Brewer H, Ibrahim NK, Booser DJ, et al. Toxicity, immunogenicity, and induction of E75-specific tumor-lytic CTLs by HER-2 peptide E75 (369–377) combined with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in HLA-A2+ patients with metastatic breast and ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3407–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaks TZ, Rosenberg SA. Immunization with a peptide epitope (p369–377) from HER-2/neu leads to peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes that fail to recognize HER-2/neu+ tumors. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4902–4908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yu Y, Zhang M, Wang W, Cao X. The involvement of TNF-α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in the enhanced cytotoxicity of IFN-β-stimulated human dendritic cells to tumor cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5407–5415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Chen H, Jiang X, Zhang M, Wan T, Li N, et al. Identification of an HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope SSp-1 of SARS-CoV spike protein. Blood. 2004;104:200–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Zhang W, He L, Xie Z, Ma S, Tao Q, et al. Lymphotactin genemodified bone marrow dendritic cells act as more potent adjuvants for peptide delivery to induce specific antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 1998;161:6238–6244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacken PJ, de Vries IJ, Torensma R, Figdor CG. Dendritic-cell immunotherapy: from ex vivo loading to in vivo targeting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:790–802. doi: 10.1038/nri2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue E, Balsari A, Campiglio M, Pupa SM. HER2 as a target for breast cancer therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:711–724. doi: 10.1517/14712591003689972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R, Esteva FJ. Herceptin: mechanisms of action and resistance. Cancer Lett. 2006;232:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT, Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, et al. A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobleigh MA, Vogel CL, Tripathy D, Robert NJ, Scholl S, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Multinational study of the efficacy and safety of humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody in women who have HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer that has progressed after chemotherapy for metastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2639–2648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengala C, Zamagni C, Pedrazzoli P, Matteucci P, Ballestrero A, da Prada G, et al. Cardiac toxicity of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer patients previously treated with high-dose chemotherapy: a retrospective study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sun H, Liu GY, Wang B, Wang F, Sun BC, et al. EBV LMP2A-specific T cell immune responses elicited by dendritic cells loaded with LMP2A protein. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:269–276. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladjemi MZ, Jacot W, Chardès T, Pèlegrin A, Navarro-Teulon I. Anti-HER2 vaccines: new prospects for breast cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1295–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono K, Takahashi A, Sugai H, Fujii H, Choudhury AR, Kiessling R, et al. Dendritic cells pulsed with HER-2/neu-derived peptides can induce specific T-cell responses in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3394–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerniecki BJ, Koski GK, Koldovsky U, Xu S, Cohen PA, Mick R, et al. Targeting HER-2/neu in early breast cancer development using dendritic cells with staged interleukin-12 burst secretion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1842–1852. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Yao K, Wang B, Chen Y, Zhou F, Guo Y, et al. Immunotherapy of Epstein-Barr virus associated malignancies using mycobacterial HSP70 and LMP2A356–364 epitope fusion protein. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:423–431. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C, Srivastava P, Bukowski R, Lacombe L, Gorelov AI, Gorelov S, et al. An adjuvant autologous therapeutic vaccine (HSPPC-96; vitespen) versus observation alone for patients at high risk of recurrence after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:145–154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]