Abstract

Highly regioselective remote hydroxylation of a natural product scaffold is demonstrated by exploiting the anchoring mechanism of the biosynthetic P450 monooxygenase PikCD50N-RhFRED. Previous studies have revealed structural and biochemical evidence for the role of a salt bridge between the desosamine N,N-dimethylamino functionality of the natural substrate YC-17 and carboxylate residues within the active site of the enzyme, and selectivity in subsequent C–H bond functionalization. In the present study, a substrate-engineering approach was conducted that involves replacing desosamine with varied synthetic N,N-dimethylamino anchoring groups. We then determined their ability to mediate enzymatic total turnover numbers approaching or exceeding that of the natural sugar, while enabling ready introduction and removal of these amino anchoring groups from the substrate. The data establish that the size, stereochemistry, and rigidity of the anchoring group influence the regioselectivity of enzymatic hydroxylation. The natural anchoring group desosamine affords a 1:1 mixture of regioisomers, while synthetic anchors shift YC-17 analogue C-10/C-12 hydroxylation from 20:1 to 1:4. The work demonstrates the utility of substrate engineering as an orthogonal approach to protein engineering for modulation of regioselective C–H functionalization in biocatalysis.

The regioselective oxidation of unactivated C–H bonds in complex molecules remains a substantial synthetic challenge.1−6 In the absence of a covalently installed directing group, the intrinsic influences of the substrate play the major role in governing regioselectivity of oxygenation. In contrast, directed methods are highly effective at overcoming the inherent reactivity of activated C–H bonds by relying on a specific binding event between the directing group and catalyst that often leads to functionalization of a C–H bond proximal to the directing group. Directed processes of this type typically involve a 5- or 6-membered transition state for the interaction of the metal with the reactive C–H bond.5,7,8 Functionalization of a region within a molecule that is remote to a directing group, while overriding the inherent reactivity of specific bonds, is not possible with these well-studied methods. Strategies to address this challenge have included the utilization of supramolecular assemblies or specialized directing groups designed to reach remote C–H bonds of the substrate;9−19 however, this type of approach remains relatively unexplored.

In nature, C–H bonds can be oxygenated by enzymes that have evolved for selectivity and efficiency. Previous work has shown that the selectivity of wild-type monooxygenases can be altered via directed evolution strategies.20 Typically, this protein-engineering approach leads to mutants with altered regioselectivity or variants that are specific for a new substrate. For example, wild-type P450 BM3 hydroxylates straight chain fatty acids and has been evolved to variants capable of oxidizing propane21 or artemisinin.22 Alternatively, understanding the mechanism of substrate binding for a particular enzyme enables substrate-engineering strategies, in which the same enzyme can be used as the catalyst for a wide range of substrates. Using these approaches, biological catalysts provide an attractive opportunity for regioselective oxidation of chemically similar bonds that are remote from directing groups.

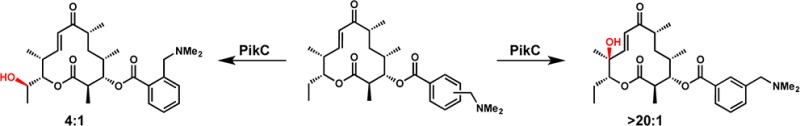

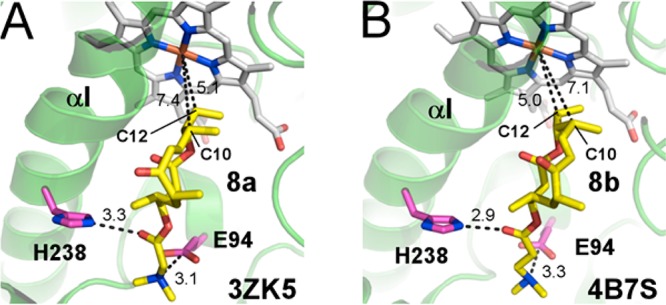

We were motivated to assess the utility of biochemically characterized bacterial P450 monooxygenase PikC from the pikromycin biosynthetic pathway as an oxidizing agent based on its known function and mechanism of substrate recognition.23 In nature, PikC is involved in the hydroxylation of the 12-membered-ring macrolide YC-17 (1) and the 14-membered-ring macrolide narbomycin (4) (Figure 1). Analysis of X-ray cocrystal structures of PikC with its natural substrates revealed largely nonspecific hydrophobic interactions between the macrolactone substrates and active-site residues. This mode of binding was leveraged in a previous study that demonstrated the ability of PikC to hydroxylate a range of substrates with an appended desosamine sugar (see 6 → 7, Figure 1c).24

Figure 1.

Reactions of PikC.

While desosamine proved to be an effective anchoring group for unnatural substrates, several practical challenges limit its utility.25 We anticipated that a simplified anchoring group capable of active-site salt bridge formation could lead to effective PikC-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization. Herein, we report in vitro implementation of a substrate-engineering approach that replaces desosamine with a range of more accessible anchoring moieties and enables tuning the regioselectivity of C–H bond oxygenation with PikCD50N-RhFRED.

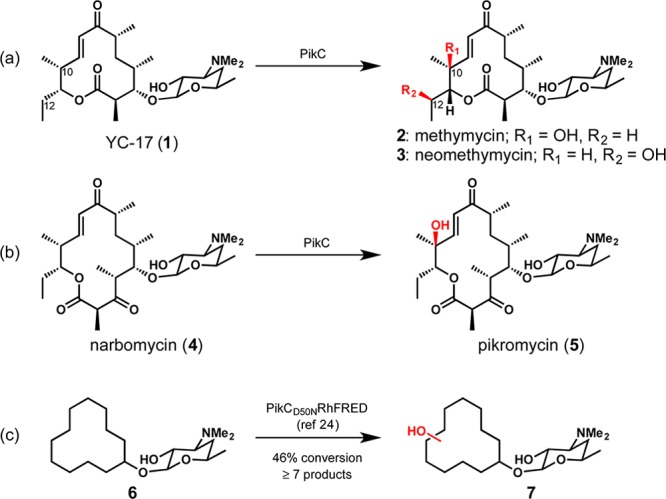

To gain insight on the factors required for an effective anchoring group, several YC-17 (1) analogues were synthesized in which the natural anchoring group, desosamine, was replaced by various tertiary-amine-containing elements (Scheme 1). For ease of synthesis and removal, synthetic anchoring groups were appended to the C-3 hydroxyl group of the YC-17 aglycone through an ester linkage. These YC-17 analogues with linear anchors (8a, 8b, and 10) were reacted with PikCD50N-RhFRED in the presence of an NADPH regeneration system to afford monohydroxylated products. The three-carbon anchoring group (see 8b) led to greater than 99% conversion of the starting material to monohydroxylated products, while anchors one carbon shorter (8a) or longer (10) resulted in slightly diminished conversions of 80% and 91%, respectively. The total turnover numbers (TTNs, no. of moles of product/no. of moles of enzyme) for 8a, 8b, and 10 were 260, 544, and 452, lower than the TTN of 896 for the natural substrate (1) of PikC. The binding affinities for 8a, 8b, and 10 also suggest that 8b is a superior substrate compared to 8a or 10, with Kd = 81 μM, approximately 4 times greater than the Kd for natural substrate YC-17 (1). To gauge the importance of the amine moiety within the synthetic anchoring groups, the dimethylamino group in 8a and 8b was replaced with an isopropyl group.26 Consistent with PikC E94 mutant studies previously reported,27 these substrates were unable to participate in salt bridge formation and were not hydroxylated.

Scheme 1. Hydroxylation of YC-17 Analogues Possessing Synthetic Anchoring Groups.

Reaction conditions: 5 μM PikCD50N-RhFRED, 1 mM substrate, 1 mM NADP+, 1 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 5 mM glucose-6-phosphate for NADPH regeneration in 50 μL of reaction buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.3, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM dithioerythritol, and 10% glycerol). Percent conversion was assessed by loss of starting material (measured by LCMS, quantified by comparison to standard curve). Isolated yield from preparative-scale reactions shown in parentheses. Product ratios are given as C10:C12 hydroxylation, and the major product is illustrated.

In addition to achieving reactivity of PikC with YC-17 analogues, we envisioned that synthetic anchoring groups would be able to control the regioselectivity of C–H bond oxygenation in a macrolactone system. PikC hydroxylates its natural substrate, YC-17 (1), at C-10 or C-12 to produce a 1:1 mixture of methymycin (2) and neomethymycin (3). We sought to identify unnatural anchors that could favor the production of methymycin (2) or neomethymycin (3) analogues. The 3-(dimethylamino)propanoate derivative 8b displayed an altered regioselectivity compared to the enzyme’s natural substrate, YC-17 (1), with C-12 oxygenation favored over hydroxylation of the allylic C-10 position (1:3).28 Shortening the linker by one methylene unit, N,N-dimethylamino ethanoate derivative 8a afforded a 1:1.6 ratio of C-10 and C-12 hydroxylated products. By contrast, extending the linker by one methylene unit, oxygenation of N,N-dimethylamino butanoate analogue 10 favored hydroxylation at the allylic C-10 position (1.8:1). These results demonstrated that anchor length had a modest effect on the regioselectivity of the oxidation of distal C–H bonds.

Based on results of the linear anchoring groups, we considered that more structurally rigid forms might lead to superior substrate binding and selectivity. Thus, N-methylproline anchoring groups (see 12a and 12b) were assessed for their reactivity with PikCD50N-RhFRED. While we envisioned one proline enantiomer would correspond to a matched case with the catalyst and the opposite enantiomer would be mismatched, both d- and l-proline derivatives performed equally well as anchoring groups. Compared to the two-carbon linear anchor (8a) that places the dimethylamino group the same number of bonds away from the macrolactone core, proline compounds 12a and 12b possessed superior TTNs of 456 and 485 and lower Kd values of 47 and 28 μM, respectively. Regioselectivity of 10-dml C–H bond oxygenation was also influenced by more-rigid cyclic anchoring groups. 10-dml derivatives containing both enantiomers of N-methylproline (12a and 12b) resulted in preferential C-10 hydroxylation by PikC in contrast to substrate 8a.

A second class of cyclic anchors that employed benzylic amines as anchoring groups was also investigated (14, 16a, and 16b). Using 0.5 mol % enzyme, 14, 16a, and 16b were converted to monohydroxylated products, and TTNs for these aryl substrates were measured at 0.1 mol % enzyme. The ortho derivative (14) displayed a low TTN of 152, while the para and meta derivatives (16a and 16b) displayed greater TTNs than the linear anchors (602 and 580, respectively).

A significant improvement in regioselectivity was observed with benzylic amines. Ortho derivative 14, which places the anchoring amine group the same number of carbon atoms away from the macrolactone core as 10, afforded a reversal of regioselectivity compared to 10 to favor C-12 hydroxylation. Increasing the distance between the ester carbonyl and the terminal N,N-dimethylamino group with para and meta derivatives 16a and 16b led to a highly regioselective allylic hydroxylation at C-10 with up to 20:1 selectivity for meta derivative 16b. We hypothesize that the more rigid anchors restrict the conformational freedom of the substrate in the active site, thus enhancing the selectivity of the enzymatic reaction.

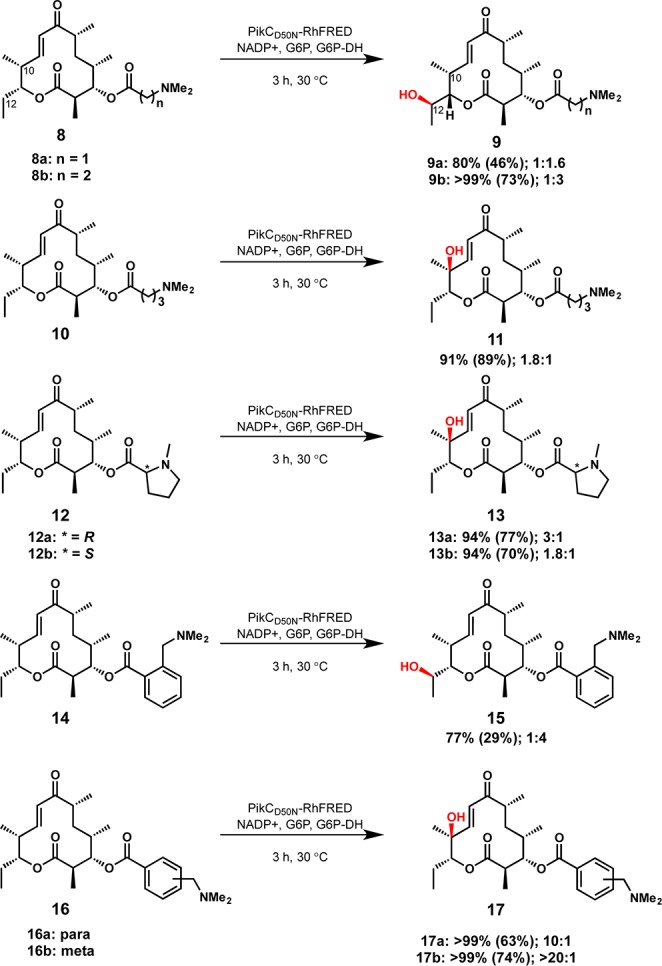

To establish the substrate binding orientation within the active site, X-ray structures of catalytically competent compounds 8a and 8b bound within the active site of PikCD50N were obtained. The salt-bridge contact between the N,N-dimethylamino group of the synthetic anchor and E94 was preserved in these complexes as in natural substrate binding (Figure 2). Additionally, a new hydrogen-bonding interaction between H238 and the ester carbonyl group of the anchor emerged in the active site for both 8a and 8b.

Figure 2.

Active site of PikCD50N with 8a (A) and 8b (B) bound. Substrates are in yellow, heme in gray, and amino acid residues in pink sticks; fragments of protein structure are shown as green ribbon. Distances are in angstroms.

To test impact of the H-bond between H238 and the anchoring group carbonyl on substrate binding, the double mutant PikCD50N/H238A-RhFRED was generated. With the D50N/H238A mutant, TTN for the natural substrate YC-17 (1) was within experimental error compared to that of the D50N mutant (896 vs 842), whereas substrates containing unnatural anchoring groups were hydroxylated by the double mutant with higher TTNs (Table 1). While the TTNs were uniformly affected by the new mutation, the dissociation constants for 8a, 12a, and 12b decreased, indicating improved binding. In contrast, the Kd values for 8b and 10 increased, suggesting lack of benefit from the H-bond for 8b and 10 analogues.

Table 1. TTNs and Kd Values of Unnatural Substrates with PikCD50N and PikCD50NH238A Mutants.

| TTN |

Kd (μM)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| substrate | D50N | D50NH238A | D50N | D50NH238A |

| 1 | 896 ± 0.71 | 842 ± 16 | 19 | nd |

| 8a | 260 ± 11 | 572 ± 18 | 118 ± 21 | 11 ± 0.56 |

| 8b | 544 ± 23 | 870 ± 38 | 81 ± 15 | 161 ± 25 |

| 10 | 452 ± 5.0 | 853 ± 38 | 123 ± 14 | 168 ± 19 |

| 12a | 456 ± 5.0 | 542 ± 30 | 47 ± 3.0 | 19 ± 1.3 |

| 12b | 485 ± 21 | 538 ± 20 | 28 ± 5.4 | 21 ± 0.70 |

| 14 | 152 ± 11 | 491 ± 26 | nd | nd |

| 16a | 602 ± 3.5 | 816 ± 33 | nd | nd |

| 16b | 580 ± 11 | 922 ± 35 | nd | nd |

The measurement of Kd values for the benzylic amine substrates was inhibited by the background absorbance of these compounds; thus, dissociation constants were not obtained for 14, 16a, and 16b.

In the current study, the inherent substrate flexibility of PikC was exploited to expand substrate scope using readily available and easily manipulated desosamine mimics as anchoring groups. As a result, the regioselectivity of the PikC C–H bond oxygenation can be controlled by the structure of the anchoring group. In contrast to typical synthetic C–H bond activation strategies that leverage proximal groups or differing C–H bond strengths, our substrate-engineering approach utilizes removable anchoring groups to achieve regioselective oxidation of remote sites within a molecule. The size and rigidity of the anchoring group correspond to significant changes in regioselectivity of the C–H bond hydroxylation. This focused study demonstrates the potential of this strategy as an effective means of expanding the substrate scope of the PikC monooxygenase. By this approach, regions of substrates were oxidized distal to the alkyl amino functionality, rendering the regioselectivity patterns orthogonal to those achieved by either directed or nondirected small-molecule oxidation catalysts.1−11 Based on X-ray structure analysis, substrate orientation within the PikC active site was controlled by the electrostatic interaction of the N,N-dimethylamino moiety with the E94 carboxylate group.

Substrate engineering has provided new insights into the structural parameters that govern productive substrate binding and conversion of potential P450 substrates. It also provides new information toward developing a general method for regio- and stereoselective oxidation of highly complex molecules, including secondary metabolites. There is a long-standing demand for enzymes with improved activity and substrate tolerance that can be applied toward chemoenzymatic synthesis of novel therapeutics, materials, fuels, and commodity chemicals. Bacterial biosynthetic P450s offer a unique source of biocatalysts for the selective oxidation of C–H bonds for a broad range of substrate classes. Efforts to improve the substrate scope, regioselectivity, and yields through substrate and protein engineering are underway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM078553 and the H. W. Vahlteich Professorship (D.H.S.). S.N. acknowledges training grant support from the University of Michigan Chemistry-Biology Interface (CBI) training program (NIH grant 5T32GM008597-14). A.R.H.N. acknowledges the Life Sciences Research Foundation for a postdoctoral fellowship. K.C.C. acknowledges training grant support from the Pharmacological Sciences Training Program (NIH grant GM007767). The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The authors thank Dr. Shengying Li for helpful discussions and the staff members of beamline 8.3.1, James Holton, George Meigs, and Jane Tanamachi, at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for assistance with data collection.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

‡ S.N. and A.R.H.N. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Chen M. S.; White M. C. Science 2007, 318, 783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutekunst W.; Baran P. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse T.; Baran P. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. S.; White M. C. Science 2010, 327, 566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons T. W.; Sanford M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H.; Engle K. M.; Shi B. F.; Yu J. Q. Science 2010, 327, 315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A. R.; Sanford M. S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 2439. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons E. M.; Hartwig J. F. Nature 2012, 483, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leow D.; Li G.; Mei T.-S.; Yu J.-Q. Nature 2012, 486, 518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Incarvito C. D.; Crabtree R. H.; Brudvig G. W. Science 2006, 312, 1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Brudvig G. W.; Crabtree R. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R.; Baldwin S.; Flechtner T.; Kalicky P.; Liu S.; Washburn W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Gabriele B.; Belvedere S.; Huang Y.; Breslow R. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 5058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco P. A.; Stuk T. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 7799. [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. T.; Neumann R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 2900. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R. Acc. Chem. Res. 1980, 13, 170. [Google Scholar]

- Gormisky P. E.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L.; Canta M.; Font D.; Prat I.; Ribas X.; Costas M. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenbacher R. V.; Samsonenko D. G.; Talsi E. P.; Bryliakov K. P. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S. T.; Lauchli R.; Arnold F. H. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasan R.; Meharenna Y. T.; Snow C. D.; Poulos T. L.; Arnold F. H. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 383, 1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Shafer B. M.; Demars M. D. I.; Stern H. A.; Fasan R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Ouellet H.; Sherman D. H.; Podust L. M. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Chaulagain M. R.; Knauff A. R.; Podust L. M.; Montgomery J.; Sherman D. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 104, 18463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desosamine can be obtained in nine steps from commercially available materials or harvested from erythromycin. Once obtained, a minimum of four additional synthetic steps are required to obtain desosaminyl substrates. Further, following enzymatic oxygenation, removal of the desosamine directing group required harsh conditions not compatible with all substrates.; Oh H. S.; Kang H. Y. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Oh H.-S.; Xuan R.; Kang H.-Y. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10-dml was coupled to isovaleric acid or 4-methylvaleric acid.

- Sherman D. H.; Li S.; Yermalitskaya L. V.; Kim Y.; Smith J. A.; Waterman M. R.; Podust L. M. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisova S. A.; Zhao L.; Sherman D. H.; Liu H.-w. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.