Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the involvement of Cl− channels in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF)-mediated relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries.

Methods:

Cl− channel and Kir channel activities were studied using whole-cell patch clamping in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. Isometric tension of arterial rings was measured in organ chambers.

Results:

The volume-activated Cl− current in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells was abolished by Cl− channel blockers NPPB or DIDS. The EDHF-mediated vasorelaxation was potentiated by NPPB and DIDS. The EDHF response was diminished by a combination of apamin and charybdotoxin, which agreed with the hypothesis that EDHF response involves the release of K+ via the Ca2+-activated K+ channels in endothelial cells. The elevation of K+ concentration in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L induced an arterial relaxation, which was abolished by the combination of BaCl2 and ouabain. It is consistent to the hypothesis that K+ activates K+/Na+-ATPase and inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels, leading to the hyperpolarization and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. The K+-induced relaxation was augmented by NPPB, DIDS, or withdrawal of Cl− from the bathing solution, which could be reversed by BaCl2, but not ouabain. The potentiating effect of Cl− channel blockers on K+-induced relaxation was probably due to the interaction between Cl− channels and Kir channels. Moreover, the K+-induced relaxation was potentiated when the arteries were incubated in hyperosmotic solution, which is known to inhibit volume-activated Cl− channels.

Conclusion:

The inhibition of Cl− channels, particularly the volume-activated Cl− channels, may potentiate the EDHF-induced vasorelaxation through the Kir channels.

Keywords: endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, chloride channels, potassium channels

Introduction

In blood vessels, endothelia control vascular smooth muscle tone by releasing various relaxing and contracting factors1. In addition to nitric oxide and prostacyclin, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) is another important relaxing factor released from endothelial cells2. EDHF is so-termed since its vasodilating effect is associated with the membrane hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells. Increasing evidence has suggested that EDHF may be particularly crucial to the regulation of tone of small resistance arteries and arterioles3. Although the identity of EDHF remains unknown, the two most recognized candidates are K+ and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET), which is a product of the cytochrome P450 pathway4, 5. The mechanisms by which K+ induces membrane hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells have been proposed for years4. According to this hypothesis, intracellular Ca2+ level in endothelial cells is elevated when the cells are stimulated by agonists (eg acetylcholine). It results in the activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels, such as intermediate- and small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (IKCa and SKCa) channels. The opening of those Ca2+-activated K+ channels causes an efflux of K+ from the intracellular compartment toward the extracellular space. A small increases in the concentration of K+ in myoendothelial space can subsequently activate the inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels4 and Na+/K+-ATPase6 in vascular smooth muscle cells. The net outcome is hyperpolarization and thus relaxation of the smooth muscle cells.

Cl− channels are ubiquitous in all cell types including vascular smooth muscle cells7, 8. A variety of biological functions of Cl− channels have been identified and the most important two are the regulations of cell volume and intracellular pH9. Cl− channels also play a key role in modulating the membrane potential of vascular smooth muscle9. Any change of the membrane potential can influence the activation states of voltage-dependent ion channels and their conductances10, 11, 12, 13. As mentioned above, EDHF response is mediated through the activation of Kir channels and Na+/K+-ATPase. Their activities may be voltage-dependent. Therefore, in theory, a change in the activity of Cl− channels should have a significant impact on the EDHF response. In the present study, we sought to reveal the relationship between Cl− channels and EDHF-mediated vasorelaxation.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissue preparation

A total of 180 male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 350–450 g were supplied from the Laboratory Animal Unit of the University of Hong Kong. Rats were anesthetized by pentobarbitone sodium (50 mg/kg, by intraperitoneal injection) and then sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The rat mesenteric arteries (first-order branch) were dissected out. All experiments performed in this study were approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research of the University of Hong Kong.

Isometric tension measurement

Isolated rat mesenteric arteries were cut into rings (1.5–2 mm in length) and were suspended in organ chambers containing low K+ Krebs solution (mmol/L: 118 NaCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 11.1 glucose, pH 7.4), aerated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. All the arterial rings were connected to a force transducer (Powerlab model ML785 and ML119; AD Instruments, Inc, Colorado Spring, CO). The rings were stretched progressively to their optimal resting tension (1.5 g; determined in preliminary experiments) and were allowed to equilibrate for 60 min. The rings were contracted by phenylephrine (0.1–10 μmol/L) to give a maximal contraction and then relaxed by acetylcholine (10 μmol/L). Arteries that could be relaxed by more than 80% reflected the presence of endothelium. When necessary, endothelium-denuded vessels were prepared by inserting the tip of a small forceps in the arterial rings and rolling them back and forth. The loss of relaxing response to acetylcholine indicated the absence of endothelia. Subsequently, the arteries were washed and phenylephrine (1 μmol/L) was applied to give another contraction (approximately 70% of maximal force) before relaxation. The degree of relaxation was expressed as the percentage decrease in the contraction to phenylephrine.

The effect of extracellular Cl− removal from the bathing solution was studied in certain experiments. The arterial rings were bathed in a low K+-Krebs solution (1.2 mmol/L) in which all Cl− was replaced by their gluconate equivalents. When the effect of osmolarity was investigated, a modified isotonic low K+-Krebs solution (300 mOsmol) containing (mmol/L): 105 NaCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES and 90 mannitol (pH 7.3) was used. Hypotonic solution (220 mOsmol) was prepared by omitting mannitol from the isotonic solution, whereas the hypertonic solution (380 mOsmol) was prepared by increasing mannitol to 120 mmol/L.

Primary culture of rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells

After removal of adherent fat and connective tissue, rat mesenteric arteries were minced and digested with 1% collagenase I for 15 min at 37 °C, followed by filtration through a 100-μm nylon mesh. The cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were incubated in 5% CO2/95% O2 at 37 °C. After 5–7 days, cells were harvested. The identity of vascular smooth muscle cells was confirmed by positive staining with anti-α-actin antibody (a smooth muscle cell marker) and negative staining with anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 antibody (an endothelial cell marker).

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings

Whole-cell currents of rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells were recorded using patch clamping14. Cells were seeded onto 35-mm culture dishes. Patch pipettes (tip resistance 3–5 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass tubes (1.5 mm outer diameter), fire polished, and then filled with internal solution containing: 125 mmol/L CsCl, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 10 mmol/L 1,2-bis (2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), 1 mmol/L MgSO4, 5 mmol/L CsOH, 2 mmol/L ATP, and 0.5 mmol/L GTP (pH 7.2, adjusted with CsOH). The cells were superfused with a modified isotonic Krebs solution (300 mOsmol) containing: 105 mmol/L NaCl, 6 mmol/L CsCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.5 mmol/L CaCl2, 10 mmol/L glucose, 10 mmol/L HEPES, and 90 mmol/L mannitol (pH 7.3 adjusted with 1 mol/L NaOH). Volume-activated Cl− current was activated by exposing the cells to hypotonic Krebs solution (220 mOsmol), which was prepared by omitting mannitol from isotonic Krebs solution. Kir current was studied as described previously15. External solution contained 140 mmol/L KCl, 0.33 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L HEPES, and 16.6 mmol/L glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette-filling solution contained 115 mmol/L K-aspartate, 25 mmol/L KCl, 5 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L Mg-ATP, 1 mmol/L EGTA, and 10 mmol/L HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH. After seal formation (seal resistance 1–10 GΩ), whole-cell currents were recorded with an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). Currents were measured at different membrane potentials, which were achieved by depolarizing voltage pulses from a holding potential of −50 mV to test potentials ranging from −100 to +100 mV in 10 mV increments. Every voltage pulse lasted for 2.1 s and the time between voltage pulses was 1.5 s, in which no recording took place. Sampling rate was set at 500 μs. Data were digitized with a Digidata 1200 analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments), and analyzed with Clampfit 9.0 software (Axon Instruments). Whole-cell current was normalized to cell capacitance and was expressed as pA/pF.

Chemicals

DMEM, fetal calf serum, penicillin and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). BAPTA was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means±SEM. Comparison between two groups was analyzed using Student's t test. Comparison among three groups or more was analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post hoc comparison using the least significant difference test. P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Cl− channel blockers potentiated EDHF-mediated relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries

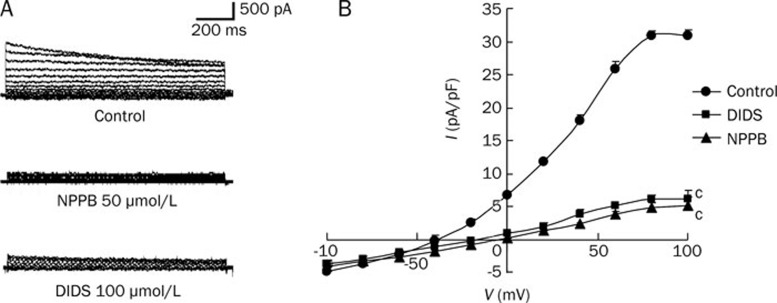

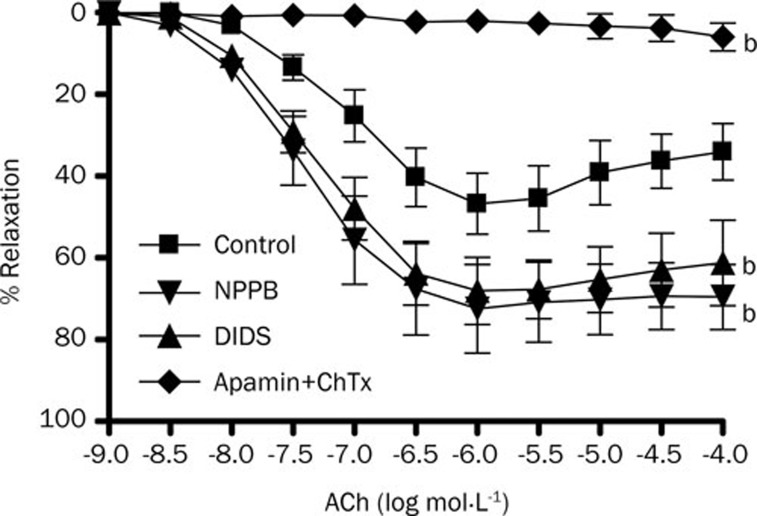

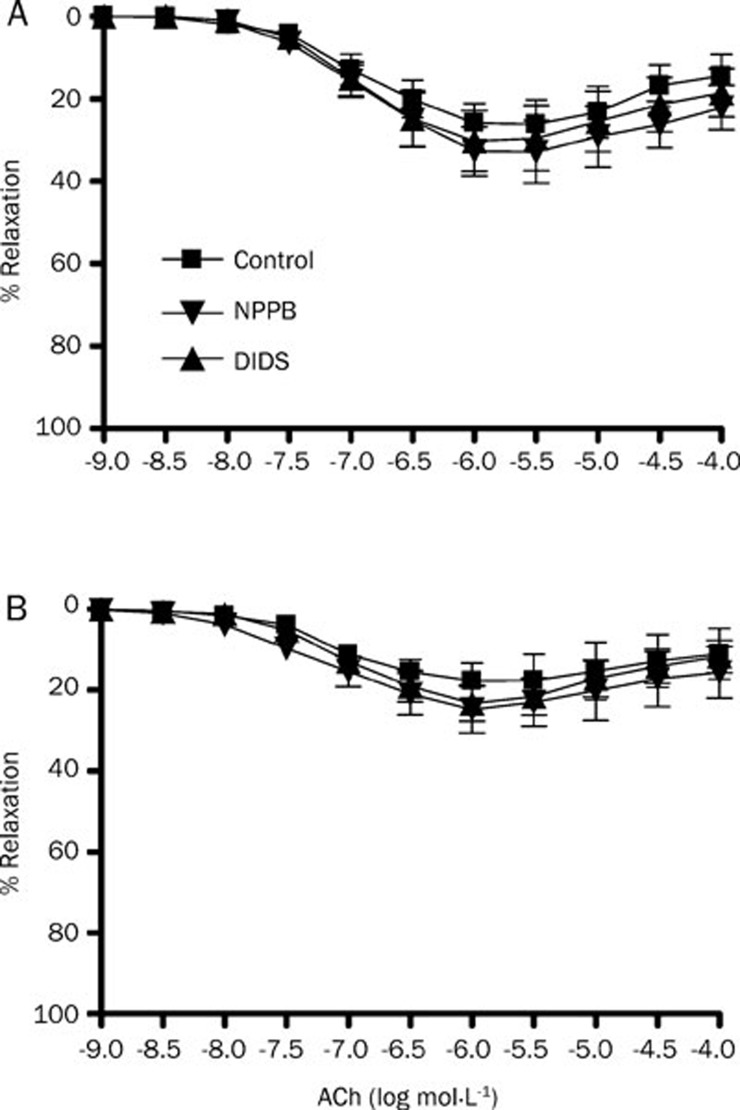

Whole-cell patch clamping demonstrates that volume-activated Cl− current in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells was abolished by Cl− channel blockers NPPB (50 μmol/L) and DIDS (100 μmol/L) (Figure 1). The same concentrations of NPPB and DIDS could directly induce a relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries by 10% approximately but it is of statistical insignificance (data not shown). To study the EDHF response, acetylcholine (1 μmol/L)-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries was measured in the presence of L-NAME (a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, 100 μmol/L) and indomethacin (a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, 30 μmol/L)16. The maximum EDHF-mediated relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries was 46.84%±7.47%, which could be abolished by the combination of apamin and charybdotoxin (Figure 2). When the arterial rings were pre-treated with NPPB (50 μmol/L) or DIDS (100 μmol/L), the maximum amplitude of EDHF-mediated relaxation was significantly augmented to 72.54%±10.83% or 68.15%±8.19%, respectively (P<0.05, n=6) (Figure 2). In contrast, NPPB (50 μmol/L) and DIDS (100 μmol/L) had no effect on the nitric oxide-mediated relaxation (acetylcholine-induced relaxation in the presence of indomethacin, apamin and charybdotoxin) (Figure 3A) nor the prostacyclin-mediated relaxation (acetylcholine-induced relaxation in the presence of L-NAME, apamin and charybdotoxin) (Figure 3B).

Figure 1.

Effects of Cl− channel blockers on volume-activated Cl− currents in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. (A) Sample traces of whole-cell currents were studied at different voltages generated by stepwise depolarization, in steps of 10 mV, from −100 to +100 mV, with a holding potential of −50 mV. Volume-activated Cl− currents were activated by exposing the cells to a hypotonic extracellular solution in the absence (control) or presence of 100 μmol/L DIDS or 50 μmol/L NPPB (n=6). (B) Current-voltage relationship for steady state current measured at different membrane potentials. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6).

Figure 2.

Effects of Cl− channel blockers on endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arterial rings. Arteries were treated with 100 μmol/L L-NAME and 3 μmol/L indomethacin for 30 min, followed by contraction by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine and then relaxation by acetylcholine (ACh). Experiments were performed in the absence (control) and presence of 50 μmol/L NPPB and 100 μmol/L DIDS, and 50 nmol/L apamin plus 50 nmol/L charybdotoxin. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). bP<0.05 compared with control group.

Figure 3.

Effects of Cl− channel blockers on nitric oxide and prostanoids-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries. Arteries were treated with 50 nmol/L apamin plus 50 nmol/L charybdotoxin and (A) 3 μmol/L indomethacin or (B) 100 μmol/L L-NAME for 30 min, followed by contraction by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine and then relaxation by acetylcholine (ACh). Experiments were performed without (control) or with 50 μmol/L NPPB or 100 μmol/L DIDS. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6).

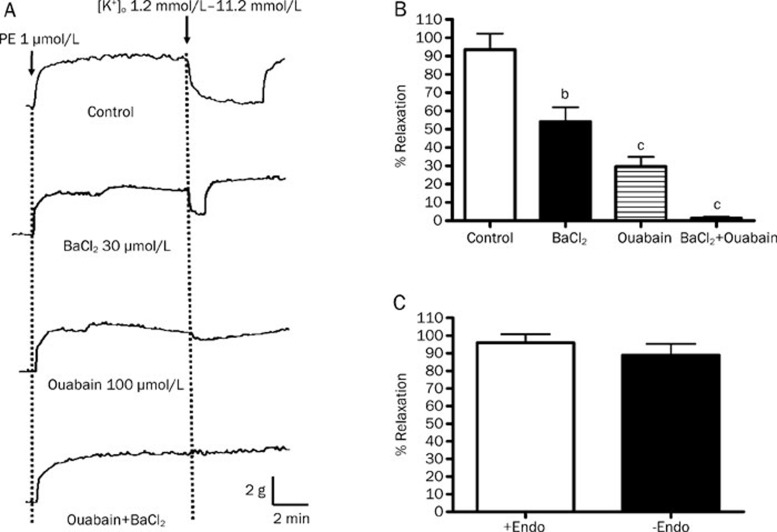

Inhibition of Cl− channels potentiated K+-induced relaxation

A relaxing response of 93.48%± 8.69% was induced in rat mesenteric arteries when K+ concentration in the bathing solution was raised from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L (Figures 4A & 4B). The amplitude of this K+-induced relaxation was the same in the arteries with or without endothelium (Figure 4C). In the presence of ouabain (Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor) or BaCl2 (a Kir channel blocker), the K+-induced vasorelaxation was reduced to 29.60%±5.25% and 54.10%±7.93%, respectively. The K+-induced relaxation could be abolished when a combination of ouabain and BaCl2 was used.

Figure 4.

Effects of Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor and Kir blocker on the K+-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries. Arteries were incubated in solution containing 1.2 mmol/L K+. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induce relaxation. (A) Sample traces of K+-induced relaxation and (B) % relaxation induced by K+ without (control) and with 100 μmol/L ouabain and/or 30 μmol/L BaCl2. (C) % relaxation induced by K+ in the rat mesenteric arteries with or without endothelium. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01, compared with control group.

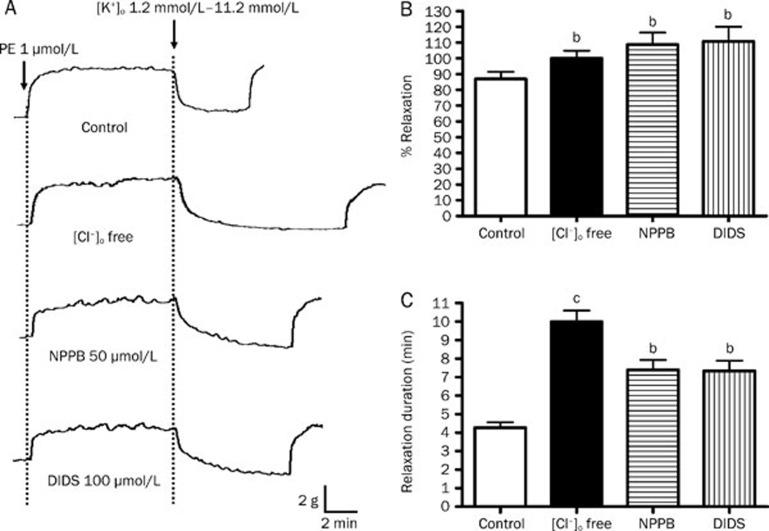

As shown in Figure 5, the peak amplitudes of K+-induced vasorelaxation were augmented from 86.98%±4.55% to 108.74%±7.51% and 110.81%±9.33% by NPPB (50 μmol/L) and DIDS (100 μmol/L) , respectively (P<0.05, n=6) (Figure 5B). In addition, the durations of relaxation were notably prolonged by NPPB and DIDS from 4.27±0.30 min to 7.38±0.65 min and 7.33±0.66 min, respectively (both P<0.05) (Figure 5C). Same as Cl− channel blockers, the removal of Cl− from the bathing solution (which subsequently reduced intracellular Cl− level and hence decreased Cl− outflux across cell membrane) augmented the peak amplitude (86.98%±4.55% to 100.04%±4.81%; P<0.05) and prolonged the duration (4.27±0.30 min to 9.98±0.61 min; P<0.05) of K+-induced relaxation (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effect of inhibition of Cl− channels on K+-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries. Arteries were incubated in solution containing 1.2 mmol/L K+. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induce relaxation. (A) Sample trace of K+-induced relaxation, (B) % relaxation of K+-induced relaxation and (C) duration of K+-induced relaxation without (control) or with 50 μmol/L NPPB, 100 μmol/L DIDS, or omission of Cl− from the bathing solution. Data were expressed as means± SEM (n=6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with control group.

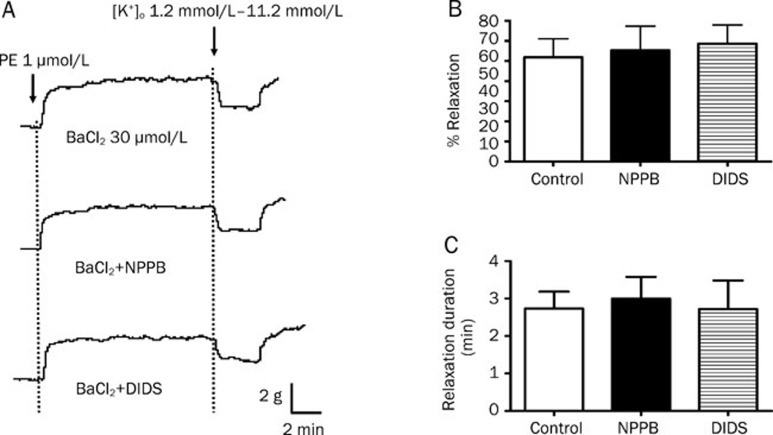

The potentiating effects of Cl− channel blockers on K+-induced relaxation was reversed by BaCl2 but not ouabain

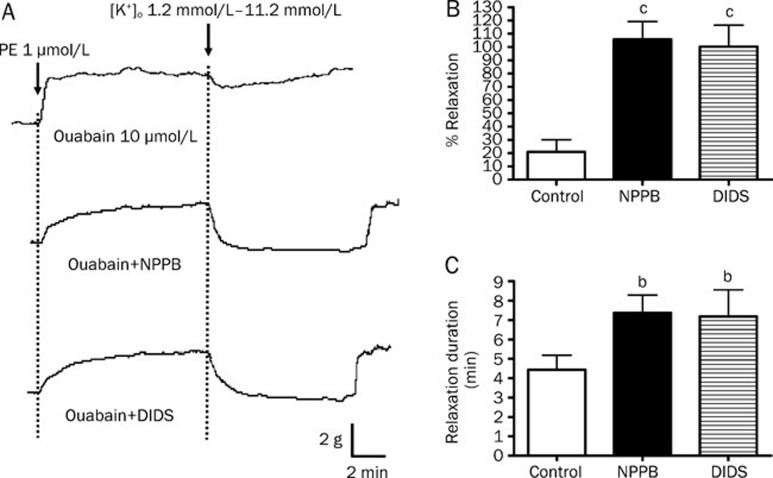

When the arterial rings were pre-incubated with BaCl2, the potentiating effects of NPPB and DIDS on the amplitudes and durations of K+-induced relaxations were prevented (Figure 6). In contrast, in the presence of ouabain, NPPB and DIDS could still increase the amplitude and duration of K+-induced relaxation (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of Kir blocker on K+-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries enhanced by Cl− channel blockers. Arteries were incubated in solution containing 1.2 mmol/L of K+ in the presence of 30 μmol/L BaCl2. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induce relaxation. (A) Sample trace of K+-induced relaxation, (B) % relaxation of K+-induced relaxation and (C) duration of K+-induced relaxation without (control) or with 50 μmol/L NPPB or 100 μmol/L DIDS. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with control group.

Figure 7.

Effect of Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor on K+-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries enhanced by Cl− channel blockers. Arteries were incubated in solution containing 1.2 mmol/L K+ in the presence of 100 μmol/L oubain. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induce relaxation. (A) Sample trace of K+-induced relaxation, (B) % relaxation of K+-induced relaxation and (C) duration of K+-induced relaxation without (control) or with 50 μmol/L NPPB or 100 μmol/L DIDS. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with control group.

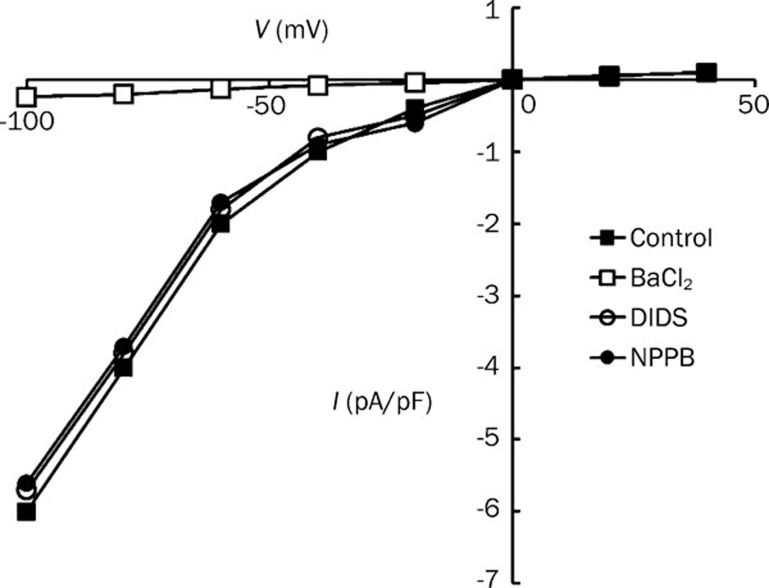

Whole-cell patch clamping was performed to study whether or not NPPB and DIDS can activate Kir channels directly. As shown in Figure 8, Kir channels in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells was abolished by BaCl2 (50 μmol/L) but was not affected by NPPB (50 μmol/L) nor DIDS (100 μmol/L).

Figure 8.

Effects of Cl− channel blockers on Kir currents in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. Whole-cell currents were measured in the absence (control) or presence of 50 μmol/L BaCl2, 100 μmol/L DIDS or 50 μmol/L NPPB. Current-voltage relationship for steady state current was measured at different membrane potentials. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=4).

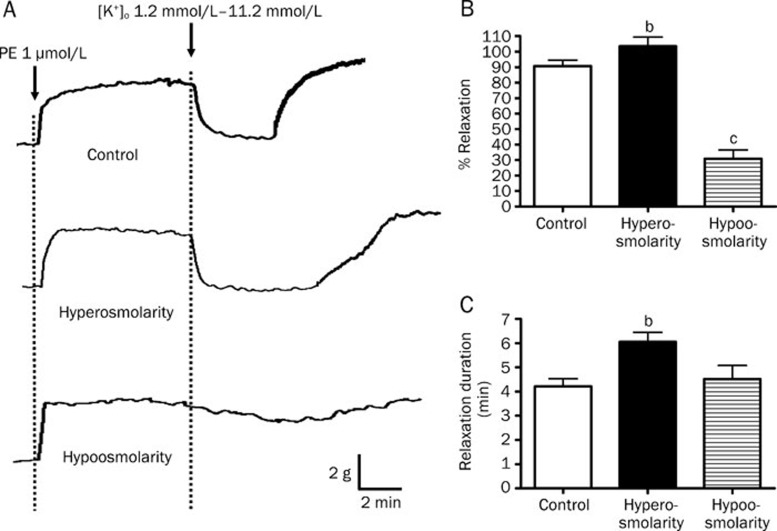

Effects of osmolarity on the K+-induced relaxation

It is known that the volume-activated Cl− channels can be activated by challenging cells with an extracellular hypotonic solution9. Therefore, additional experiments were performed to investigate the impact of osmolarity on K+-induced relaxation. When the bathing solution was changed from isotonic to hypertonic, the peak amplitude of K+-induced relaxation was significantly increased from 90.69%±3.89% to 103.42%±5.95% (P<0.05, n=6), and the duration of relaxation was also prolonged from 4.22±0.32 min to 6.05±0.40 min (P<0.05, n=6) (Figure 8).

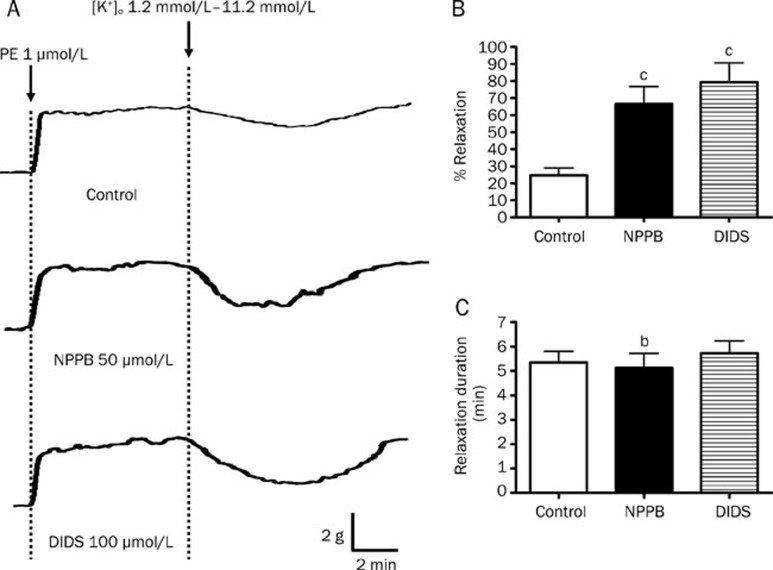

In contrast, amplitude of relaxation was markedly decreased to 30.89%±5.67% while the duration of relaxation remained unchanged when the bathing solution was changed from isotonic to hypotonic (P<0.01, n=6) (Figure 9). Further experiments were carried out to study whether or not the decreased K+-induced relaxations under hypotonic condition could be reversed by the Cl− channel blockers NPPB and DIDS. As shown in Figure 10, the peak amplitudes of K+-induced vasorelaxation under hypotonic condition were significantly increased from 24.73%±4.38% to 66.61%±10.15% and 79.36%±11.36% by NPPB (50 μmol/L) and DIDS (100 μmol/L), respectively (P<0.01, n=6). However, the durations of relaxation were not affected by NPPB and DIDS under hypotonic condition.

Figure 9.

Effects of hyperosmolarity and hypoosmolarity on K+-induced relaxation in rat mesenteric arteries. Arteries were incubated in normal bathing solution (300 mOsmol; control), hyperosmotic solution (300 mOsmol) or hypoosmotic solution (220 mOsmol) containing 1.2 mmol/L K+ in the presence of 100 μmol/L oubain. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induced relaxation. (A) Sample trace of K+-induced relaxation, (B) % relaxation of K+-induced relaxation and (C) duration of K+ -induced relaxation. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). bP<0.05, cP<0.01 compared with control group.

Figure 10.

Effects of Cl− channel blockers on K+-induced relaxation under hypotonic condition. Arteries were incubated in hypoosmotic solution (220 mOsmol) containing 1.2 mmol/L K+. Arteries were then contracted by 1 μmol/L phenylephrine followed by changing the K+ level in bathing solution from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L to induce relaxation. Experiments were performed in the absence (control) and presence of 50 μmol/L NPPB and 100 μmol/L DIDS. (A) Sample trace of K+-induced relaxation, (B) % relaxation of K+-induced relaxation and (C) duration of K+-induced relaxation. Data were expressed as means±SEM (n=6). cP<0.01 compared with control group.

Discussion

The present study provides a direct evidence that blockade of Cl− channels potentiates the EDHF-mediated relaxation response, but had no effects on nitric oxide- or prostacyclin-mediated relaxations in rat mesenteric arteries. Although the identification of EDHF remains under debate, K+, which effluxes from the endothelial cells through the Ca2+-activated K+ channels (especially IKCa and SKCa channels) has been suggested as a proposed candidate of EDHF. Consistent to other studies4, we demonstrated that the EDHF-mediated relaxation could be abolished when the Ca2+-activated K+ channels were blocked by apamin and charybdotoxin17. Indeed, the vasorelaxant effect of K+ has been found for over 70 years18. A number of investigations have strongly suggested that K+ manifests as an important regulatory factor, which enhances blood flow and meets the metabolic needs of active tissues. For instance, the exercise-induced increase in blood flow to skeletal muscle is associated with an increase in the K+ of the venous outflow19, 20, 21, 22. Many studies have been carried out to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the vasorelaxing effect of K+. Increased activities of the Na+/K+-ATPase and Kir channels on vascular smooth muscle cells are the two distinct mechanisms that have been most reported2, 4, 23, 24. In line with this hypothesis, our present study showed that ouabain (a Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor) and BaCl2 (a Kir channel blocker) inhibited the relaxing effect of K+ on rat mesenteric arteries.

Nevertheless, the hypothesis that K+ is a vasodilatator has been challenged by several studies that failed to demonstrate the relaxation induced by raising K+ concentration25, 26, despite the existence of EDHF response in those arteries. It has been demonstrated that small rat mesenteric arteries did not relax when K+ concentration in bathing solution was raised from 5.9 mmol/L to 11.2 or 21.2 mmol/L. However, when the initial K+ level was lowered to 1.2 mmol/L, an increase in K+ concentration could evoke a relaxation response27. In agreement with these early reports, our study showed that rat mesenteric arteries relaxed when the K+ concentration in the bathing solution was raised from 1.2 mmol/L to 11.2 mmol/L. The interpretation of these results might be that maintaining the K+ in a low initial concentration such as 1.2 mmol/L could reduce the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase, and hence leading to a decrease in intracellular K+ level. When extracellular K+ is subsequently raised, the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase is increased28, 29, which can generate outward current and promote relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells. By contrast, when a higher initial concentration of K+ such as 5.9 mmol/L is used, the level of Na+/K+-ATPase activity has been nearly saturated so further increase in extracellular K+ exerts little or negligible effect on Na+/K+-ATPase. 1.2 mmol/L of K+ is probably a physiological concentration. Although the K+ concentration in the myoendothelial gap in mesenteric arteries has not been measured, it has been reported that the interstitial concentration of K+ in skeletal muscle at rest is 1.02±0.08 mmol/L30.

Our study demonstrated that the pharmacological blockade of Cl− channels augmented the amplitude and duration of K+-induced vasorelaxation. Based on the data from patch clamp studies, the mechanism likely involves the interaction between Cl− channels and Kir channels, instead of the direct activation of Kir channels by Cl− channel blockers. Cl− channels are abundant in the vascular smooth muscle cells31 and act as one of the major determinants of the membrane potential. Theoretically, a change in Cl− conductance may influence the activity of other voltage-sensitive channels or transporters32. As shown in the present study, the potentiating effects of Cl− channel blockers on K+-induced relaxations were only reversed by Kir channel blocker BaCl2, but not by Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain. This may be due to the different electrophysiological properties of Kir channels and Na+/K+ ATPase. It is hitherto contradictory whether or not the Na+,K+-ATPase is voltage-dependent1, 11. However, Kir channels have been proved to be voltage-dependent12, which hyperpolarize cells by passing outward current in the voltage range just positive to the equilibrium potential of K+(EK)32. It is known that the equilibrium potential of Cl− (ECl) is about 60 mV positive in relation to EK. Therefore, if the cell membrane potential is dominated by Cl− conductance, there will be little or no outward K+ current. It may account for the poor relaxing response to K+ in certain vascular beds25, 26. However, when the Cl− channels are blocked (or when the Cl− outflux is attenuated), the membrane potential of the vascular smooth muscle cells is shifted to EK, which may result in the increase of outward K+ current through Kir channels, and subsequently enhances the membrane hyperpolarization and vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Similar to our findings, a previous study has suggested that inhibition of Cl− channels enhanced K+ efflux through Kir channels, thereby increasing dilatation of pressurized rat mesenteric arteries33. However, unlike our study, the authors hypothesized that the interaction between Cl− channels and Kir channels happened in endothelial cells, rather than vascular smooth muscle cells.

The physiological or pharmacological significance of the potentiating effect on EDHF response by inhibition of Cl− conductance is not clear but it may account for the regulation of blood flow in association with osmolarity change. Two major classes of Cl− channels have been found in vascular smooth muscle cells, namely Ca2+-activated Cl− channels and volume-activated Cl− channels34. A well-established functional role of volume-activated Cl− channels is their contribution to cell volume regulation since these channels can be activated by hypoosmolarity9. In healthy volunteers, intravenous infusion of hypertonic dextrose or NaCl solutions has been found to increase forearm blood flow as a result of a decrease in resistance35. Similarly, intravascular infusion of hypertonic solutions has been shown to increase cerebral blood flow36, 37. Sasaki and co-workers suggested that hypertonic solutions produce non-specific vasodilation of cerebral arteries by inhibiting the influx of external Ca2+ rather than the release of intracellularly stored Ca2+38. In line with those studies, our results show that hyperosmolarity can augment the vasorelaxing effect of K+. We speculate that the increase in blood flow by hyperosmolarity may be accounted by the inhibition of volume-activated Cl− channels, which potentiates the EDHF-mediated vasodilatory response.

The potentiating effect on EDHF response by blockade of Cl− channels may also be relevant to the action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). It has been reported that EETs hyperpolarize and relax coronary arteries by activating BKCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells39, 40, 41, 42, probably through a G-protein-depending signaling pathway43. In addition, EETs may also stimulate vanilloid transient receptor potential channels 444, which increase Ca2+ influx, and subsequently activate BKCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. However, it has been demonstrated that around one-third of the 14,15-EET-induced relaxation of coronary artery is resistant to BKCa channel blocker45, 46. It clearly indicates that other ion channels may be involved in EETs-induced relaxation. Our previous study has revealed the inhibitory effect of EETs on volume-activated Cl− channels14. It has also been reported that inhibition of Cl− channels partly contributes to the hyperpolarizing and relaxing effects of 5,6-EET and 11,12-EET on tracheal smooth muscle47, 48, 49.

In summary, our present study suggests that blockade of Cl− channels potentiates EDHF-induced relaxation of rat mesenteric arteries, and this potentiating effect is likely linked to Kir channels. Our findings extend the knowledge on the roles of Cl− channels in blood vessels, and may increase the understanding on the mechanisms of EDHF-mediated vasodilatory response.

Author contribution

Cui YANG performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; Yiu-wa KWAN, Shun-wan CHAN and Simon Ming-yuen LEE provided ideas and reagents; George Pak-heng LEUNG designed research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the RGC Earmarked Grants of Hong Kong SAR (project code: 769607), and the Seed Funding for Basic Research Program of the University of Hong Kong.

References

- Furchgott RF, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. FASEB J. 1989;3:2007–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félétou M, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: where are we now. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1215–25. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000217611.81085.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félétou M, Vanhoutte PM. EDHF: new therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Res. 2004;49:565–80. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, Weston AH. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature. 1998;396:269–72. doi: 10.1038/24388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I, Busse R. Endothelium-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and vascular function. Hypertension. 2006;47:629–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000208597.87957.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior HM, Webster N, Quinn K, Beech DJ, Yates MS. K+-induced dilation of a small renal artery: no role for inward rectifier K+ channels. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:780–90. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szücs G, Buyse G, Eggermont J, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Characterization of volume-activated chloride currents in endothelial cells from bovine pulmonary artery. J Membr Biol. 1996;149:189–97. doi: 10.1007/s002329900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DG, Nelson MT, Eckman DM, Brayden JE. Swelling-activated cation channels mediate depolarization of rat cerebrovascular smooth muscle by hyposmolarity and intravascular pressure. J Physiol. 2000;527:139–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Eggermont J, Voets T. Droogmans G. Volume-activated Cl− channels. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:1131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahinski A, Nakao M, Gadsby DC. Potassium translocation by the Na+/K+ pump is voltage insensitive. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3412–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch HG. Electrophysiology of the sodium-potassium-ATPase in cardiac cells. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1791–826. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG, Lopatin AN. Inward rectifier potassium channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:171–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WF. Ion channels and vascular tone. Hypertension. 2000;35:173–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Kwan YW, Seto SW, Leung GP. Inhibitory effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on volume-activated chloride channels in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2008;87:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WS, Kim N, Youm JB, Warda M, Ko JH, Kim SJ, et al. Angiotensin II inhibits inward rectifier K+ channels in rabbit coronary arterial smooth muscle cells through protein kinase Calpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:728–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng KF, Leung SW, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor mediated relaxations in pig coronary arteries do not involve Gi/o proteins. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29:1419–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluais P, Edwards G, Weston AH, Falck JR, Vanhoutte PM, Félétou M. Role of SK(Ca) and IK(Ca) in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations of the guinea-pig isolated carotid artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144:477–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SE. The influence of the Ca and K ions on toners and adrenaline response of the coronary arteries. Arch Intern Pharmacodyn. 1936;54:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner NS, Powell WJ. Action of oxygen and potassium on vascular resistance of dog skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1967;212:533–40. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.212.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellmer I. The potassium ion as a vasodilatator during muscular exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 1965;63:460–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1965.tb04089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell H, Pernow B. Effect of exercise on plasma potassium of man. Acta Physiol Scand. 1966;66:241–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JJ, Mohr M, Klarskov C, Kristensen M, Krustrup P, Juel C, et al. Effects of high-intensity intermittent training on potassium kinetics and performance in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2004;554:857–70. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.050658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron JG, Halpern W. Potassium dilates rat cerebral arteries by two independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H902–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY, Liang GH, Kim JA, Park SH, Hah JS, Suh SH. Contribution of Na+-K+ pump and Kir currents to extracellular pH-dependent changes of contractility in rat superior mesenteric artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H792–800. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00050.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy PS, Pilkington G, Hanvesakul R, Fish HJ, Boyle JP, Thurston H. Evidence against potassium as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat mesenteric small arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:605–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty JM, Boyle JP, Langton PD. Blockade of Cl− channels reveals relaxations of rat small mesenteric arteries to raised potassium. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:293–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochet DX, Langton PD. Dual effect of initial [K] on vascular tone in rat mesenteric arteries. Pflugers Arch. 2006;453:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddy FJ. Potassium effects on contraction in arterial smooth muscle mediated by Na+, K+-ATPase. Fed Proc. 1983;42:239–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns SP, Flatman JA, Clausen T. Relation between extracellular [K+], membrane potential and contraction in rat soleus muscle: modulation by the Na+-K+ pump. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:909–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01837404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gao Z, Kehoe V, Sinoway LI. Interstitial K+ concentration in active muscle after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H808–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00295.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Morita T, Iwamoto T. Diversity of Cl− channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:12–24. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5336-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B, Schwarz W. Potassium channels as multi-ion single-file pores. J Gen Physiol. 1978;72:409–42. doi: 10.1085/jgp.72.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty JM, Boyle JP, Langton PD. Potassium does not mimic EDHF in rat mesenteric arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1174–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Droogmans G. Amazing chloride channels: an overview. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:119–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeck HW, Grega GJ. Response of the limb vascular bed in man to intrabrachial arterial infusions of hypertonic dextrose or hypertonic sodium chloride solutions. Circ Res. 1970;26:717–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardebo JE, Nilsson B. Hemodynamic changes in brain caused by local infusion of hyperosmolar solution, in particular relation to blood-brain barrier opening. Brain Res. 1980;181:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassell NF, Baumann KW, Hitchon PW, Gerk MK, Hill TR, Sokoll MD. The effects of high dose mannitol on cerebral blood flow in dogs with normal intracranial pressure. Stroke. 1982;13:59–61. doi: 10.1161/01.str.13.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kassell NF, Fujiwara S, Torner JC, Spallone A. The effects of hyperosmolar solutions on cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Stroke. 1986;17:1266–71. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 1996;78:415–23. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Harder DR. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors and vascular cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the regulation of tone. Circ Res. 1999;84:484–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H, Gutterman DD. Human coronary arteriolar dilation to arachidonic acid depends on cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase and Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Circ Res. 1998;83:501–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YF, Huang L, Morgan JP. Cytochrome P450: a novel system modulating Ca2+ channels and contraction in mammalian heart cells. J Physiol. 1998;508:777–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.777bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li PL, Campbell WB. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids activate K+ channels in coronary smooth muscle through a guanine nucleotide binding protein. Circ Res. 1997;80:877–84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ Res. 2005;97:1270–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194321.60300.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Deeter C, Gauthier KM, Ingraham RH, Falck JR, Li PL. 14,15-Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid relaxes bovine coronary arteries by activation of KCa channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1656–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00597.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BT, Miura H, Hatoum OA, Campbell WB, Hammock BD, Zeldin DC, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic and dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids dilate human coronary arterioles via BKCa channels: implications for soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H491–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00927.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang TC, Guggino SE, Guggino WB. Direct modulation of secretory chloride channels by arachidonic and other cis unsaturated fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5706–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvail D, Cloutier M, Rousseau E. Functional reconstitution of an eicosanoid-modulated Cl− channel from bovine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C567–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvail D, Dumoulin M, Rousseau E. Direct modulation of tracheal Cl−-channel activity by 5,6- and 11,12-EET. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L432–41. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]