Abstract

Hyperuricemia-mediated uric acid crystal formation may cause joint inflammation and provoke the destruction of joints through the activation of inflammasome-mediated innate immune responses. However, the immunopathological effects and underlying intracellular regulatory mechanisms of uric acid crystal-mediated activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have not been elucidated. Therefore, we investigated the in vitro effects of monosodium urate crystals, alone or in combination with the inflammatory cytokines tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)-α or interleukin (IL)-1β, on the activation of human FLS from RA patients and normal control subjects and the underlying intracellular signaling mechanisms of treatment with these crystals. Monosodium urate crystals were able to significantly increase the release of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6, the chemokine CXCL8 and the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 from both normal and RA-FLS (all P<0.05). Moreover, the additive or synergistic effect on the release of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 from both normal and RA-FLS was observed following the combined treatment with monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α or IL-1β. Further experiments showed that the release of the measured inflammatory cytokine, chemokine and MMP-1 stimulated by monosodium urate crystals were differentially regulated by the intracellular activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways but not the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Our results therefore provide a new insight into the uric acid crystal-activated immunopathological mechanisms mediated by distinct intracellular signal transduction pathways leading to joint inflammation in RA.

Keywords: cytokines, fibroblast-like synoviocytes, rheumatoid arthritis, signal transduction, uric acid

Introduction

Arthritis is the most common cause of joint pain and physical disability in developed countries and worldwide.1 Gout is an acute inflammatory arthritis whose incidence has increased over the past decade, which is characterized by elevated serum urate concentrations and recurrent attacks by intra-articular uric acid crystal deposition.2 Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory polyarthritis with 1% prevalence in industrialized countries, which is characterized by cytokine-mediated inflammation of the synovium and destruction of cartilage and bone.3 Uric acid crystal-mediated gouty attacks have also been observed in patients with RA.4, 5 Fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) are resident mesenchymal cells in synovial joints that play crucial roles in both joint damage and the propagation of inflammation in arthritic diseases.6 The ability of FLS to erode cartilage is a multistep process that includes the attachment of FLS onto cartilage and the synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP-1.7 Additionally, FLS secrete receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, which can attract macrophages from the vasculature, stimulate the differentiation of vascular- and tissue-derived macrophages into osteoclasts and activate osteoclasts at the bone surface, leading to bone erosion.8

FLS mediate inflammation and autoimmune responses through complex mechanisms during the development of inflammatory RA.9 FLS can produce a broad range of pro-inflammatory molecules such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)-α, as well as the secretion of MMPs through the activation of multiple intracellular signal transduction pathways including extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK).10, 11 These pro-inflammatory molecules lead to further FLS activation and the recruitment, accumulation and survival of a number of immune effector cells including leukocytes, endothelial cells, neutrophils and osteoclasts in the synovium.9 IL-6, a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, was originally described as a T cell-derived B-cell differentiation factor that is essential for antibody production by activated B cells and may stimulate the production of autoantibodies such as rheumatoid factor in RA.12 Chemokines produced by FLS can promote the chemotactic migration of mononuclear cells into local inflammatory sites, leading to the adaptive immune response and contributing to the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases.13 MMPs released from FLS have pathological roles in arthritic diseases leading to tissue destruction by degrading the components of the extracellular matrix.14

Uric acid, a major component released into the extracellular milieu from necrotic cells, can act as a damage-associated molecular pattern molecule, and initiate and perpetuate a non-infectious inflammatory response.15 Uric acid is an end product of the purine metabolic pathway that is found in blood and interstitial spaces, and its accumulation can lead to crystallization and trigger an auto-inflammatory response.16 Uric acid crystals play an important role in both gouty arthritis and immune regulation through the activation of inflammasome-mediated innate host defense mechanisms in robust inflammation.15 In innate immunity, uric acid crystals can induce the maturation of dendritic cells and augment the priming of CD8+ T cells to cross-presented antigens.17 Uric acid crystals can also activate macrophages to produce the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 through the direct activation of a central cytosolic sensor, the NALP3 inflammasome.18 However, recent studies revealed that uric acid crystals could also regulate acquired immunity.16 Uric acid can augment CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses and enhance IgG1 antibody-mediated immunity in mice, thereby activating the humoral immune response.16 Some studies have indicated that uric acid can trigger the NALP3 inflammasome to result in caspase 1-dependent IL-1β production in lung injury inflammation and fibrosis.19 During acute arthritis attacks, uric acid crystal deposition has been demonstrated to stimulate synovial cells, monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils to produce a panel of different inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6 and monocyte chemotactic factor, for the induction of acute joint inflammation.20 Moreover, uric acid crystal deposition in joints or skin can lead to leukocyte infiltration, deformation of joints and thickening of synovial walls in long-term inflammation.15 Injection of uric acid crystals into joints of healthy humans and canines can reproduce gout symptoms such as the sudden onset of a hot, red and swollen joint.15 However, the immunopathological effects and underlying intracellular regulatory mechanisms of uric acid crystal-mediated activation of FLS have not been elucidated. We herein hypothesize that hyperuricemia-mediated uric acid crystal formation plays a crucial role in further enhancing joint inflammation by activating FLS via distinct intracellular mechanisms in RA. In this study, we have therefore elucidated the immunopathological roles of uric acid crystals in joint inflammation and the in vitro activating effect of monosodium urate crystals in combination with TNF-α or IL-1β on FLS from RA and control subjects and the underlying intracellular signal mechanism.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Uric acid was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St Louis, MO, USA). Monosodium urate crystals were prepared according to a previously published method.21 Briefly, 800 mg uric acid was dissolved in 155 ml boiling distilled water containing 5 ml of 1 mol/l NaOH. After the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7.2 by the addition of 1 mol/l HCl, the solution was cooled gradually with stirring at room temperature and then stored overnight at 4 °C. The formed monosodium urate crystals were then sterilized by heating at 180 °C for 2 h, suspended in sterilized phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and used in each experiment by adding directly to the culture medium to achieve the desired concentration. In this preparation, the endotoxin level of the monosodium urate crystals was found to be undetectable (<0.1 EU/ml) using the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (sensitivity limit 12 pg/ml; BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA).

Recombinant human TNF-α and IL-1β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The ERK inhibitor U0126, JNK inhibitor SP600125, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase inhibitor LY294002, Janus kinase inhibitor AG490 and IκB-α phosphorylation inhibitor BAY-11-7082 were purchased from Calbiochem Corp. (San Diego, CA, USA). SB203580 was dissolved in water, whereas PD98059, LY294002, SP600125, AG490 and BAY-11-7082 were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide. In all studies, the concentration of dimethylsulfoxide was 0.1% (v/v).

Endotoxin-free solutions

Cell culture medium was purchased from Cell Applications Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), free of detectable lipopolysaccharide (<0.1 EU/ml). All other solutions were prepared using pyrogen-free water and sterile polypropylene plastic ware. No solution contained detectable LPS, as determined by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker).

Cell culture of FLS

Human FLS isolated from synovial tissues obtained from normal control healthy subjects and patients with RA were purchased from Cell Applications. FLS were cultured in synoviocyte growth medium including 10% synoviocyte growth supplement (Cell Applications) in 5% CO2–95% humidified air at 37 °C.11 Experiments using human primary cells were approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Hospitals.

Assay for human IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1

The concentrations of IL-6 and CXCL8 in culture supernatants following equal cell number loading were measured simultaneously by bead-based multiplex cytokine assay using a BD cytometric bead array (CBA) (BD Pharmingen Corp., San Diego, CA, USA) using a four-color FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences Corp., San Jose, CA, USA). Human MMP-1 in culture supernatants was assayed by ELISA (RayBiotech Inc., Norcross, GA, USA).11

Intracellular staining of activated (phosphorylated) signaling molecules

The intracellular expression of phosphorylated signaling molecules was determined quantitatively using previously established intracellular staining methods using flow cytometry.11, 22 This quantitative flow cytometric method for the analysis of the activation of intracellular signaling molecules by intracellular staining of phosphorylated signaling molecules is less tedious than western blot, and the flow cytometric method requires fewer cells and a reduced assay time. Briefly, cells were fixed with pre-warmed BD Cytofix Buffer (4% paraformaldehyde) for 10 min at 37 °C following stimulation by monosodium urate crystals. After centrifugation, the cells were permeabilized in ice-cold methanol for 30 min and then stained with mouse antihuman phosphorylated ERK and phosphorylated JNK monoclonal antibodies or a mouse IgG1 isotype control (BD Pharmingen) for 60 min followed by FITC-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibody (BD Pharmingen) for another 45 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were then washed, resuspended and subjected to analysis. Expression of the intracellular phosphorylated signaling molecules in 5000 viable cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences) in terms of mean fluorescence intensity.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significances of differences were determined by one-way ANOVA. The values were expressed as the mean±s.d. from three independent experiments. Any difference with a P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. When ANOVA indicated a significant difference, the Bonferroni post hoc test was used to assess the difference between groups. All analyzes were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistical software for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Monosodium urate crystals can induce IL-6 and CXCL8 production from FLS

Figure 1a and c shows that stimulation of normal control FLS and RA-FLS with monosodium urate crystals (200 µg/ml) results in a significant increase in IL-6 and CXCL8 production at 48 h (all P<0.01). The release of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and the chemokine CXCL8 from RA-FLS was significantly higher than the release of these inflammatory mediators from control FLS (all P<0.01). When the kinetics and dose–response of monosodium urate crystals on the release of IL-6 and CXCL8 were examined, monosodium urate crystals (100–200 µg/ml) were able to significantly increase the release of IL-6 and CXCL8 at all incubation times (24–72 h) in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 1b and d). In view of the above results, we mainly used a 48-h incubation time and 200 µg/ml dose of monosodium urate crystals in the following studies to induce significant stimulation.

Figure 1.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of monosodium urate crystals on the induction of IL-6 and CXCL8 release from FLS. Control and RA-FLS were cultured with or without monosodium urate crystals (200 µg/ml) for 48 h and the induction of (a) the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and (c) the chemokine CXCL8 were analyzed by CBA using flow cytometry. Control and RA-FLS were stimulated with or without monosodium urate crystals (0–200 µg/ml) for 24–72 h and the induction of (b) IL-6 and (d) CXCL8 were analyzed by CBA using flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CBA, cytometric bead array; CTL, medium control; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; IL, interleukin; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

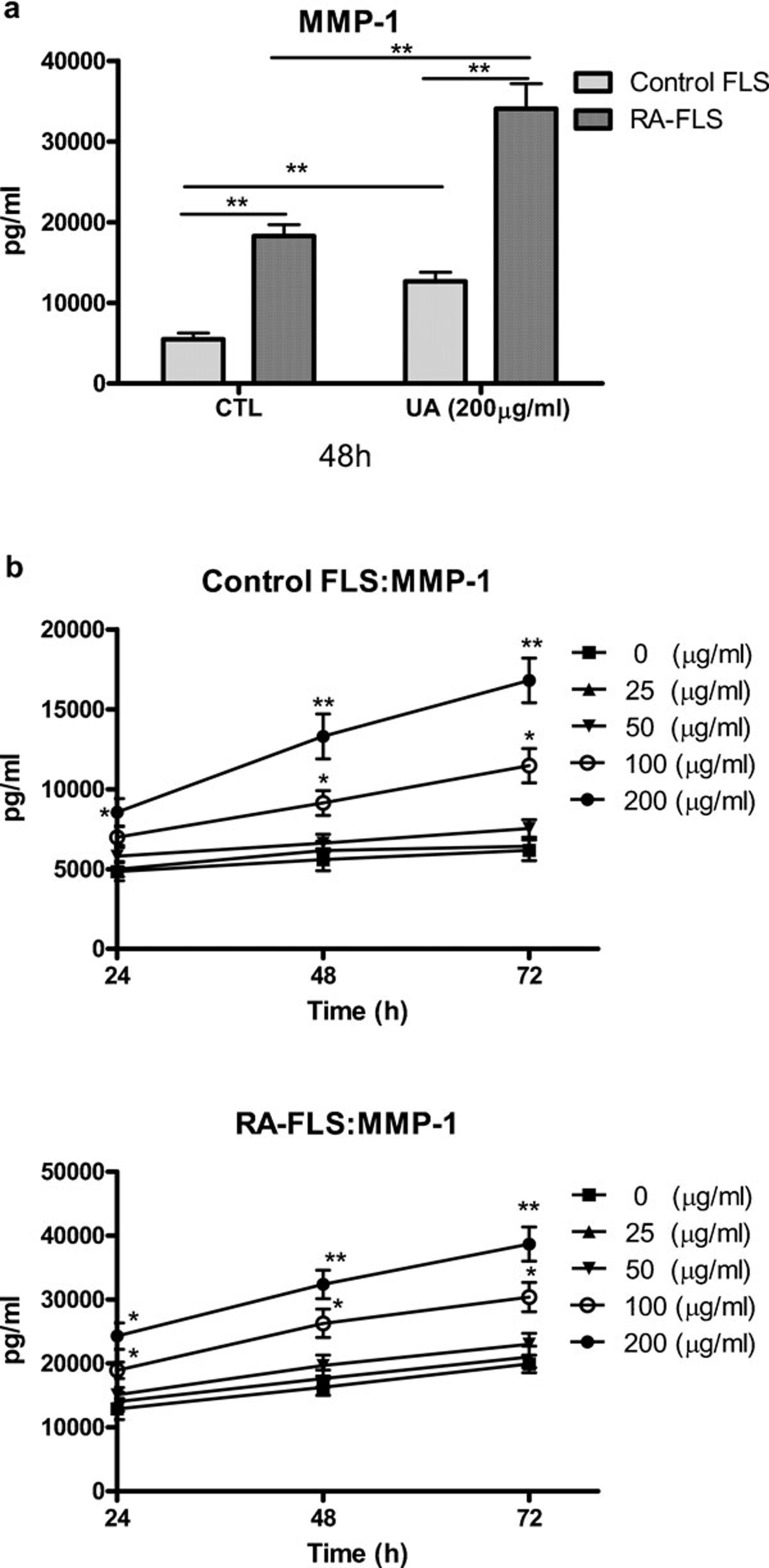

Monosodium urate crystals could increase MMP-1 production from FLS

As shown in Figure 2a, the stimulation of normal FLS and RA-FLS with monosodium urate crystals (200 µg/ml) resulted in a significant increase in MMP-1 production at 48 h. The release of MMP-1 from RA-FLS was significantly higher than that of normal FLS (P<0.01). When the kinetics and dose–response of monosodium urate crystal-induced release of MMP-1 were examined, monosodium urate crystals (100–200 µg/ml) were able to significantly increase the release of MMP-1 at all the incubation times (24–72 h) in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of monosodium urate crystals on the induction of MMP-1 release from FLS. (a) Control and RA-FLS were cultured with monosodium urate crystals (200 µg/ml) for 48 h and the induction of MMP-1 was analyzed by ELISA. (b) Control and RA-FLS were stimulated with monosodium urate crystals (0–200 µg/ml) for 24–72 h and the induction of MMP-1 was analyzed by CBA using flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CBA, cytometric bead array; CTL, control; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

Monosodium urate crystals can enhance TNF-α-induced IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from FLS

As the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α plays a crucial inflammatory role in the joints of arthritis patients,23 we further investigated the combined effect of monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α on the activation of FLS. Figure 3 shows that combined treatment with monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α resulted in additive or synergistic release of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 from both normal and RA-FLS (all P<0.05). Since the addition of monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α did not increase the number of FLS, the augmented IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release was not due to an increased number of FLS.

Figure 3.

The combined effects of monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α on the induction of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from FLS. Control and RA-FLS were cultured with or without monosodium urate crystals (100–200 µg/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) alone or in combination for 48 h. Release of (a) IL-6, (b) CXCL8 and (c) MMP-1 were determined by CBA or ELISA. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean+s.d. of three independent experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 when compared between treatment group and medium control. #P<0.05 when compared between combined treatment group and single treatment group. CBA, cytometric bead array; CTL, control; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor-necrosis factor; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

Monosodium urate crystals can enhance IL-1β-induced IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from FLS

As the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β also plays a crucial inflammatory role in the joints of arthritis patients,23 we further investigated the combined effect of monosodium urate crystals and IL-1β on the activation of FLS. Figure 4 shows that combined treatment with monosodium urate crystals and IL-1β results in additive or synergistic release of CXCL8 and MMP-1 but not IL-6 from normal or RA-FLS (all P<0.05). Since the addition of monosodium urate crystals and IL-1β did not increase the number of FLS, the augmented CXCL8 and MMP-1 release was not due to the increased number of FLS.

Figure 4.

The combined effects of monosodium urate crystals and IL-1β on the induction of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from FLS. Control and RA-FLS were cultured with or without monosodium urate crystals (100–200 µg/ml) and IL-1β (20 ng/ml) alone or in combination for 48 h. Release of (a) IL-6, (b) CXCL8 and (c) MMP-1 were determined by CBA or ELISA. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean+s.d. of three independent experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 when compared between treatment group and medium control. #P<0.05, when compared between combined treatment group and single treatment group. CBA, cytometric bead array; CTL, control; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

Effects of monosodium urate crystals on the activation of JNK and ERK signaling pathways in FLS

Using intracellular fluorescence staining by flow cytometry, we measured the mean fluorescence intensity of phosphorylated JNK and ERK in permeabilized FLS following stimulation with monosodium urate crystals. As shown in Figure 5, monosodium urate crystals were able to induce significant phosphorylation of JNK and ERK in both normal and RA-FLS, with the maximal stimulation at 30 min (all P<0.05). However, monosodium urate crystals could not significantly activate p38 MAPK in both normal and RA-FLS (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effects of monosodium urate crystals on intracellular JNK and ERK activities in FLS. Normal or RA-FLS were incubated with monosodium urate crystals (200 µg/ml) for 0–60 min. The amounts of intracellular phosphorylated signaling molecules in 5000 permeabilized cells were measured by flow cytometry. Results of (a) phosphorylated JNK and (b) phosphorylated ERK are shown as mean fluorescence intensity subtracting the corresponding isotype control and are expressed as the arithmetic mean+s.d. of three independent experiments. Representative histograms illustrate the intracellular expression of (a) phosphorylated JNK and (b) phosphorylated ERK in the control or RA-FLS upon 30-min stimulation with monosodium urate crystals. The isotype control represents the cell populations stained with antimouse IgG1 isotype control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, when compared between groups denoted by horizontal lines. CTL, medium control; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

Effects of signaling molecule inhibitors on the release of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 from FLS activated by monosodium urate crystals

The cytotoxicity of different signaling molecule inhibitors on FLS was first determined using the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium assay, and the effective doses of these inhibitors with significant inhibitory effects on specific signaling pathways have been widely studied using different cell types including human FLS.11, 22, 24 Following previous publications and toxicity threshold values from the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium assay, we therefore used the following optimal concentrations of Janus kinase inhibitor AG490 (5 µM), IκB-α phosphorylation inhibitor BAY11-7082 (0.8 µM), phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase inhibitor LY294002 (5 µM), ERK inhibitor U0126 (5 µM), p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 µM) and JNK inhibitor SP600125 (5 µM) to induce significant inhibitory effects on these signaling pathways without cell toxicity. As shown in Figure 6, the ERK inhibitor U0126 and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 were able to significantly suppress monosodium urate crystal-induced IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from both normal and RA-FLS (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of signaling molecule inhibitors on monosodium urate crystal-induced IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 release from FLS. Normal and RA-FLS were pretreated with AG490 (AG, 5 µM), BAY11-7082 (BAY, 0.8 µM), LY294002 (LY, 5 µM), SB203580 (SB, 10 µM), SP600125 (SP, 5 µM) or U0126 (5 µM) for 1 h followed by incubation with or without monosodium urate crystals (UA, 200 µg/ml) in the presence of inhibitors for a further 48 h. Release of (a) IL-6, (b) CXCL8 and (c) MMP-1 were determined by CBA or ELISA. Results are expressed as the arithmetic mean+s.d. from three independent experiments. DMSO (0.1%) was used as the vehicle control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, when compared between groups denoted by horizontal lines. CBA, cytometric bead array; CTL, medium control; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; FLS, fibroblast-like synoviocytes; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UA, monosodium urate crystals.

Discussion

As FLS are key effector cells in inflammatory arthritic diseases, new agents targeting FLS may potentially complement the current therapeutics without major deleterious effects on adaptive immune responses.25 Remarkably, uric acid crystals can induce various inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, proteases and reactive oxygen species, thereby playing an important role in the development of inflammatory responses.26 Uric acid crystals have been shown to stimulate dendritic cell maturation, enhance antigen-specific immune responses and directly activate T cells.27 We have recently reported that the inflammatory cytokine IL-27 can activate FLS in RA by activating distinct intracellular signaling pathways.11 The present study further revealed that uric acid plays a crucial role in provoking inflammation by activating FLS through intracellular signal transduction mechanisms in RA.

A panel of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-2 are involved in the joints of RA patients, causing inflammation, articular destruction and the comorbidities seen in RA.23 In this study, we found that monosodium urate crystals were able to significantly induce inflammatory cytokine IL-6 release from both control and RA-FLS (P<0.05). Combined treatment with monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α also resulted in the synergistic production of IL-6 from both control and RA-FLS. This result is consistent with the previous finding that monosodium urate and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals can induce IL-6 production from synoviocytes and monocytes in vitro.28 IL-6 is one of the most important inflammatory cytokines in infection, inflammation and immunity. High levels of IL-6 can be detected in the serum and synovial fluid of patients with various inflammatory arthritic diseases such as RA, gout and juvenile idiopathic arthritis.29 IL-6 can act as a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine by promoting Th17 differentiation and inhibiting regulatory T-cell differentiation, indicating that the control of IL-6 may normalize the balance between Th17 and regulatory T cells to alleviate autoimmune symptoms.29 IL-6 not only promotes and maintains inflammation in arthritis but also contributes to the generation and maintenance of inflammatory pain by acting at nociceptive nerve cells.30 In a clinical study, anti-IL-6R antibody (tocilizumab) has been shown to be a novel therapeutic strategy for certain inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including RA and systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, with significant clinical improvement and amelioration of joint damage.31

Some studies have demonstrated that uric acid crystals can induce human eosinophils and neutrophils to produce the neutrophil chemokine CXCL8.32, 33 To examine whether uric acid crystals also modulate the expression of chemokines in FLS, we found that monosodium urate crystals were able to significantly increase the release of the chemokine CXCL8 from both control FLS and RA-FLS (P<0.05). Combined treatment of monosodium urate crystals with TNF-α or IL-1β resulted in the synergistic production of CXCL8 from control FLS (Figures 3 and 4). CXCL8, the first chemokine found to be involved in leukocyte chemotaxis, is considered to be the most important inflammatory chemokine associated with arthritis.34 CXCL8 not only is an important chemotactic cytokine for the inflammatory events, but also acts as a potent angiogenic factor in arthritis.35 Continuous infusion of human recombinant CXCL8 into rabbit knee joints can lead to the accumulation of leukocytes, the infiltration of mononuclear cells into synovial tissue and marked hypervascularization in the synovial lining layer.36 A neutralizing antibody to CXCL8 can prevent neutrophil infiltration in lipopolysaccharide/IL-1-induced arthritis and attenuate monosodium urate crystal-induced leukocyte infiltration into knee joints in rabbit.37 Uric acid crystal stimulation also leads to the increased expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in synovial fluid mononuclear cells.38 TNF-α or IL-1β can potently induce the expression of CXCL8 in cultured FLS.39 We found that monosodium urate crystals exhibited synergistic effects with TNF-α or IL-1β to induce CXCL8 release from normal FLS. Since FLS, neutrophils and mononuclear cells play important roles in the pathogenesis of arthritis, the enhanced production of the chemokine CXCL8 can attract mononuclear cells and neutrophils towards FLS downstream of monosodium urate crystals, TNF-α and IL-1β together to contribute to the development of inflammation.

MMPs, a family of zinc-containing endopeptidases, play a key role in the proteolytic degradation of damaged extracellular matrix components and in tissue repair in arthritic joints.40 Destruction of cartilage and bone is a characteristic feature of inflammatory arthritis and the production of MMPs by the inflamed synovium is considered to be critical in the pathogenesis of articular damage.40 The expression of MMP-1 is increased when the system reacts in wound healing, repair or remodeling processes in several pathological conditions.41 MMP-1 has been found in the synovial membranes and fluids of all RA patients and the expression of MMP-1 in the synovial fluid correlates with the degree of synovial inflammation.41 MMP-1, the only MMP secreted by FLS, has the capacity to digest type II collagen, which is the major type of collagen in cartilage. We found that monosodium urate crystals could induce a significant increase in MMP-1 production from both control and RA-FLS (P<0.001). Moreover, monosodium urate crystals could enhance TNF-α- or IL-1β-induced MMP-1 release from FLS (Figures 3 and 4). Combined treatment with monosodium urate crystals and TNF-α or IL-1β resulted in the synergistic production of MMP-1 from normal FLS (Figures 3 and 4). The intrinsic difference in the activation of multiple intracellular signal transduction mechanisms such as ERK may account for the higher induction of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 from RA-FLS compared to normal FLS.42, 43, 44 IL-6 and other chemokines in synovial fluid and synovium of RA patients have also been reported to be significantly elevated compared with control subjects.9, 28

Uric acid crystals have been shown to activate the MAPK (p38 MAPK, JNK and ERK1/2) signaling pathway in T-cell lines 20 and also activate the ERK signaling pathway in fibroblasts,45 but the signaling pathways downstream of uric acid crystals in FLS have not been reported. We have recently reported that the inflammatory cytokine IL-27 can stimulate FLS in RA by activation of the JNK, AKT and Janus kinase signaling pathways.11 This study showed that incubation with monosodium urate crystals resulted in elevated phosphorylation of ERK and JNK but not p38 MAPK within 30 min that was maintained for 60 min in both normal and RA-FLS (Figure 5). The JNK signaling pathway has been shown to mediate MMP-1 secretion from FLS and regulate cartilage erosion in collagen-induced arthritis.46 The ERK pathway can be activated in RA synovial tissue and cultured RA-FLS, and the principal functional sequelae of the ERK pathway have been control of cell growth and proliferation.47 Moreover, the JNK and ERK signaling pathways are involved in pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production in activated FLS.48, 49 Numerous studies have demonstrated that the inhibition of the JNK and ERK pathways has profound effects on the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and modulation of acute and chronic inflammation.50

Using selective inhibitors to suppress the activation of corresponding signaling pathways, we further elucidated the involvement of different signaling pathways in regulating the expression of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 in FLS. These inhibition experiments confirmed that monosodium urate crystal-induced IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 production was mediated by the activation of distinct JNK and ERK pathways (Figures 5 and 6). Such induction of IL-6 and CXCL8 by monosodium urate crystals in FLS was not completely inhibited by the JNK and ERK inhibitors; other unidentified signaling pathways should therefore contribute to IL-6 and CXCL8 expression. Further experiments may be required to investigate the regulatory mechanisms of different signaling molecules and transcription factors on the induction of IL-6, CXCL8 and MMP-1 in human FLS following activation by monosodium urate crystals. Because of the recent advances in the application of MAPK and NF-κB inhibitors as potential anti-inflammatory agents,50 this study should also provide new clues for the development of novel treatments for joint inflammation.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- VanItallie TB. Gout: epitome of painful arthritis. Metabolism. 2010;59:S32–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack WJ, Parker AE, O'Neill LA.Toll-like receptors and NOD-like receptors in rheumatic diseases Arthritis Res Ther243.200911243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Role of cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:397–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CF, Tsai WP, Liou LB. Rare copresent rheumatoid arthritis and gout: comparison with pure rheumatoid arthritis and a literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:231–235. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah S, Scott K, Featherstone T, Coady D. Pus, pannus or tophus: coexistent rheumatoid arthritis and gout. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16:98. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181d145fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor A, Abramson SB, Pillinger MH. The fibroblast-like synovial cell in rheumatoid arthritis: a key player in inflammation and joint destruction. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolboom TC, Pieterman E, van der Laan WH, Toes RE, Huidekoper AL, Nelissen RG, et al. Invasive properties of fibroblast-like synoviocytes: correlation with growth characteristics and expression of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-10. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:975–980. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.11.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DH, Kong YY, Penninger JM. Role of RANKL and RANK in bone loss and arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:32–39. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noss EH, Brenner MB. The role and therapeutic implications of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in inflammation and cartilage erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:252–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K, Scatizzi JC, Fiore S, Shamiyeh E, Koch AE, Firestein GS, et al. Retinoblastoma suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-1, but not interleukin-6, though a p-38-dependent pathway in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:78–87. doi: 10.1002/art.11482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CK, Chen DP, Tam LS, Li EK, Yin YB, Lam CW. Effects of inflammatory cytokine IL-27 on the activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R129. doi: 10.1186/ar3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B, Padyukov L, Lundström E, Seielstad M, Plenge RM, Oksenberg JR, et al. Different patterns of associations with anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis in the extended major histocompatibility complex region. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:30–38. doi: 10.1002/art.24135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Nagase H. Progress in matrix metalloproteinase research. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:290–308. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Mucsi AD, Ng G. Monosodium urate crystals in inflammation and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:203–217. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MD, Wagner WM, Krco CJ, Erskine CL, Kalli KR, Krempski J, et al. The endogenous danger signal, crystalline uric acid, signals for enhanced antibody immunity. Blood. 2008;111:1472–1479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Evans JE, Rock KL. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature. 2003;425:516–521. doi: 10.1038/nature01991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasse P, Riteau N, Charron S, Girre S, Fick L, Pétrilli V, et al. Uric acid is a danger signal activating NALP3 inflammasome in lung injury inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:903–913. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1274OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi T, Ka T, Yamamoto A, Moriwaki Y, Takahashi S, Tsutsumi Z, et al. Effects of ethanol on monosodium urate crystal-induced inflammation. Cytokine. 2008;42:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahoshi T, Namai R, Murakami Y, Watanabe M, Matsui T, Nishimura A, et al. Rapid induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression in human monocytes by monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:231–239. doi: 10.1002/art.10709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung PF, Wong CK, Lam CW. Molecular mechanisms of cytokine and chemokine release from eosinophils activated by IL-17F and IL-23: implications for Th17 lymphocyte-mediated allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 2008;180:5625–5635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FM, McInnes IB. Evidence that cytokines play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3537–3545. doi: 10.1172/JCI36389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip WK, Wong CK, Li ML, Li PW, Cheung PF, Lam CW. Interleukin-31 induces cytokine and chemokine production from human bronchial epithelial cells through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways: implications for the allergic response. Immunology. 2007;122:532–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahoshi T, Murakami Y, Kitasato H. Recent advances in crystal-induced acute inflammation. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:146–150. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328014529a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R, Jeffries M, Sawalha AH. Uric acid directly promotes human T-cell activation. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:23–27. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31817727af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerne PA, Terkeltaub R, Zuraw B, Lotz M. Inflammatory microcrystals stimulate interleukin-6 production and secretion by human monocytes and synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1443–1452. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780321114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1830–1835. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible HG, von Banchet GS, Boettger MK, Bräuer R, Gajda M, Richter F, et al. The role of proinflammatory cytokines in the generation and maintenance of joint pain. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1193:60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto N, Terao K, Mima T, Nakahara H, Takagi N, Kakehi T. Mechanisms and pathologic significances in increase in serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and soluble IL-6 receptor after administration of an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Castleman disease. Blood. 2008;112:3959–3964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Kouzaki H, Kita H. Human eosinophils recognize endogenous danger signal crystalline uric acid and produce proinflammatory cytokines mediated by autocrine ATP. J Immunol. 2010;184:6350–6358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Grainger R, Harrison A, Harper JL. Differences in MSU-induced superoxide responses by neutrophils from gout subjects compared to healthy controls and a role for environmental inflammatory cytokines and hyperuricemia in neutrophil function and survival. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1228–1235. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M, Loetscher P, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and the chemokine family. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(94)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekanecz Z, Szücs G, Szántó S, Koch AE. Chemokines in rheumatic diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:91–102. doi: 10.2174/138945006775270231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H, Akahoshi T, Nishimura A, Tonegawa M, Takagishi K, Kashiwazaki S, et al. Experimental arthritis induced by continuous infusion of IL-8 into rabbit knee joints. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A, Akahoshi T, Takahashi M, Takagishi K, Itoman M, Kondo H, et al. Attenuation of monosodium urate crystal-induced arthritis in rabbits by a neutralizing antibody against interleukin-8. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:444–449. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Giovine FS, Malawista SE, Thornton E, Duff GW. Urate crystals stimulate production of tumor necrosis factor alpha from human blood monocytes and synovial cells. Cytokine mRNA and protein kinetics, and cellular distribution. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1375–1381. doi: 10.1172/JCI115142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho ML, Ju JH, Kim HR, Oh HJ, Kang CM, Jhun JY, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 ligand mediates the upregulation of angiogenic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-8/CXCL8 in human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Immunol Lett. 2007;108:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu SC, Yang SF, Lue KH, Hsieh YS, Hsiao TY, Lu KH. The clinical significance of gelatinase B in gouty arthritis of the knee. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;339:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konttinen YT, Ainola M, Valleala H, Ma J, Ida H, Mandelin J, et al. Analysis of 16 different matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1 to MMP-20) in the synovial membrane: different profiles in trauma and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:691–697. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.11.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher WK, Heer AH, Trabandt A, Bridges SL, Jr, Schroeder HW, Jr, Stransky G, et al. Overexpression of zinc-finger transcription factor Z-225/Egr-1 in synoviocytes from rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Immunol. 1994;152:5940–5948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Boyle DL, Aupperle KR, Bennett B, Manning AM, Firestein GS. Jun N-terminal kinase in rheumatoid arthritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman H, Georganas C, Pagliari LJ, Koch AE, Haines K, 3rd, Pope RM. Bcl-2 expression in synovial fibroblasts is essential for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and cell viability. J Immunol. 2000;164:5227–5235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TH, Lin JW, Chao HH, Chen YL, Chen CH, Chan P, et al. Uric acid activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases and thereafter endothelin-1 expression in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillinger MH, Dinsell V, Apsel B, Tolani SN, Marjanovic N, Chan ES, et al. Regulation of metalloproteinases and NF-kappaB activation in rabbit synovial fibroblasts via E prostaglandins and Erk: contrasting effects of nabumetone and 6MNA. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:973–982. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler JF, Monahan JB, Smith WG. p38 pathway kinases as anti-inflammatory drug targets. J Dent Res. 2007;86:800–811. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volin MV, Huynh N, Klosowska K, Chong KK, Woods JM. Fractalkine is a novel chemoattractant for rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte signaling through MAP kinases and Akt. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2512–2522. doi: 10.1002/art.22806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filer A, Bik M, Parsonage GN, Fitton J, Trebilcock E, Howlett K, et al. Galectin 3 induces a distinctive pattern of cytokine and chemokine production in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts via selective signaling pathways. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1604–1614. doi: 10.1002/art.24574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA. Targeting signal transduction as a strategy to treat inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:549–563. doi: 10.1038/nrd2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]