We examined barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India, with an emphasis on the experiences of nurses, who are often the front-line providers of palliative care. Interventions must streamline process details of morphine procurement, work within the existing sociocultural infrastructure to ensure opioids reach patients most in need, target unexpected audiences for symptom management education, and account for role expectations of health care providers.

Keywords: Morphine, Palliative care, Cancer, World health, India, Opioids, Nursing, Pain management, Ethnography

Abstract

Background.

The world’s global cancer burden disproportionally affects lower income countries, where 80% of patients present with late-stage disease and have limited access to palliative care and effective pain-relieving medications, such as morphine. Consequently, millions die each year with unrelieved pain.

Objective.

The objective of this study was to examine barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India, with an emphasis on the experiences of nurses, who are often the front-line providers of palliative care.

Methods.

Fifty-nine participants were recruited using a purposive, snowball sampling strategy. Ethnographic data collection included in-depth, semistructured interviews (n = 54), 400+ hours of participant observation, and review of documents over 9 months at a government cancer hospital in South India. Systematic qualitative analysis led to identification of key barriers that are exemplified by representative quotes.

Results.

Morphine is more available at this study site than in most of India, but access is limited to patients seen by the palliative care service, and significant gaps in supply still occur. Systems to measure and improve pain outcomes are largely absent. Key barriers related to pain management include the role of nursing, opioid misperceptions, bureaucratic hurdles, and sociocultural/infrastructure challenges.

Implications.

Interventions must streamline process details of morphine procurement, work within the existing sociocultural infrastructure to ensure opioids reach patients most in need, target unexpected audiences for symptom management education, and account for role expectations of health care providers.

Conclusion.

Macro- and micro-level policy and practice changes are needed to improve opioid availability and cancer pain management in India.

Implications for Practice:

Improving access to opioid therapy for cancer patients in lower income countries involves both health policy and clinical practice efforts. Even when morphine is available, it may not reach patients in need due to health care provider lack of knowledge, limited responsibility for pain assessment and management by nursing staff, or infrastructure challenges, such as geographical distance from an urban hospital. Effective training and education must account for social and cultural factors, such as when health care providers will, or will not, advocate for patients in pain. Family caregivers and auxiliary hospital staff who may be highly involved in pain management should be included in educational interventions. It is also important to leverage the knowledge of lower-level administrators who may play a pivotal role in ensuring morphine is available for patients and to explore ways to improve access to pain relief for cancer patients who live in rural areas.

Introduction

Reliable access to strong opioids, such as morphine, is a prerequisite to delivering quality palliative care, a crucial component of global cancer control [1–3]. However, despite its designation as a World Health Organization essential medicine, morphine is drastically limited, or absent, in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as India [4–7]. This problem is significant, as 60% of the world’s cancer deaths occur in LMICs and 80% of patients in these countries present with late-stage, incurable disease [2]. This global public health crisis is increasingly viewed as a violation of basic human rights [1, 8–11].

Barriers to opioid availability are extremely complex, but a key problem involves overly restrictive laws, regulations, and licensing requirements (that commonly exceed standards established by international treaties [12]) that significantly limit the distribution of controlled substances and medical decision making of providers [13]. Additional challenges include prescriber fear related to retribution from police authorities for providing morphine to patients [11, 14], low prioritization of pain management and palliation on national health care agendas [3], geographical barriers, and disruptions inherent with war and political instability [15].

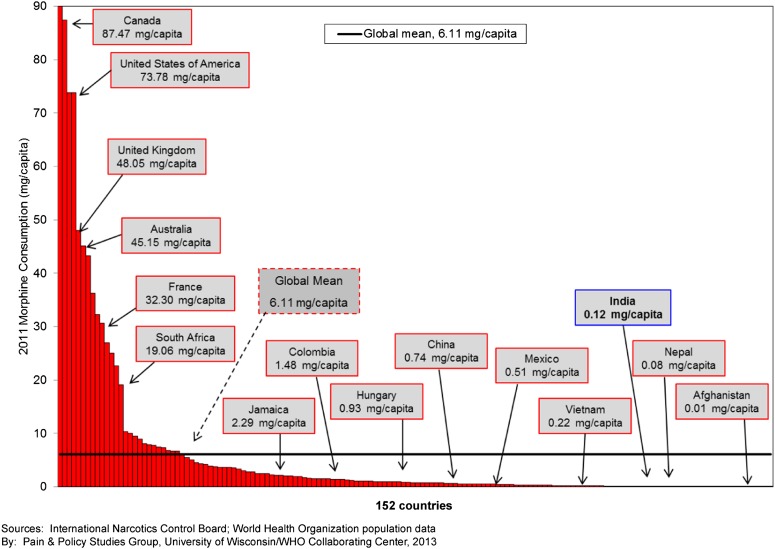

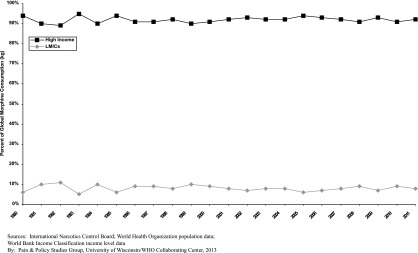

Opioid consumption data indicate that higher income countries consume a disproportionate amount of morphine for medicinal purposes compared with LMICs (Figs. 1, 2). Although certain regions in India have made tremendous progress in developing palliative care services and access to morphine, this success is relatively isolated [16–20]. Of the approximate 2.4 million people in India living with cancer, approximately 1.6 million are likely to be in pain, and it is estimated that only 0.4% of the Indian population that could benefit from opioid therapy can access the medication [19].

Figure 1.

Global comparison of morphine consumption (mg/capita), 2011.

Figure 2.

Annual total morphine consumption (kg) as a percentage of the global total morphine consumption (kg) consumed in high-income countries and LMICs. Abbreviation: LMICs, low- and middle-income countries.

Objective

The objective of this study was to describe barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India from the perspective of health care providers (HCPs), particularly oncology nurses, and offer specific recommendations to improve cancer pain management in LMICs. It was part of a larger ethnographic project whose primary objective was to explore the relationship between moral distress and opioid availability in lower income countries [21].

Methods

Design

This was a qualitative, ethnographic study.

Setting

The primary field site (South Indian Cancer Hospital [SICH, pseudonym]) is a 300-bed government cancer hospital located in a large city in South India. As a government hospital, it sees a high volume of patients (>10,000 a year) and provides care at a highly subsidized rate to those who cannot afford care in the private sector.

Sample

Participants were recruited during an informational session about the project held for SICH staff and also during hospital observations. Inclusion criteria for the primary sample (nurses) included being 18 years of age or older and spending at least 50% of clinical duties providing care to cancer patients. The secondary sample included those who interacted closely with nurses.

Data Collection

The first author (V.L.) collected data over 9 months of intensive field immersion from September 2011 to June 2012. Semistructured interviews were audio-recorded (with permission) and lasted approximately 1 hour. Questions were open-ended and elicited experiences of caring for cancer patients with pain and challenges related to pain management and opioid use. A translator fluent in the local language assisted as necessary. Observational data (more than 400 hours) were recorded daily as field notes and triangulated with data from interviews and review of relevant documents.

Data Analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed and cleaned, and accuracy of translation was verified by two native speakers of the local language. Field notes were edited and organized chronologically [22]. Formal interview transcripts were coded with Dedoose version 4.5.91, using a systematic coding schema supplemented by open coding as concepts emerged from the analysis. Details of study procedures and analysis have been reported elsewhere [23]. This work describes results from the thematic analysis [24] of data related to opioid availability and cancer pain management.

Ethical Considerations

Approval was obtained from both the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the SICH Ethics Committee before data collection. Participants who agreed to be formally interviewed consented using an IRB-approved form. Participants and location were de-identified to protect confidentiality.

Results

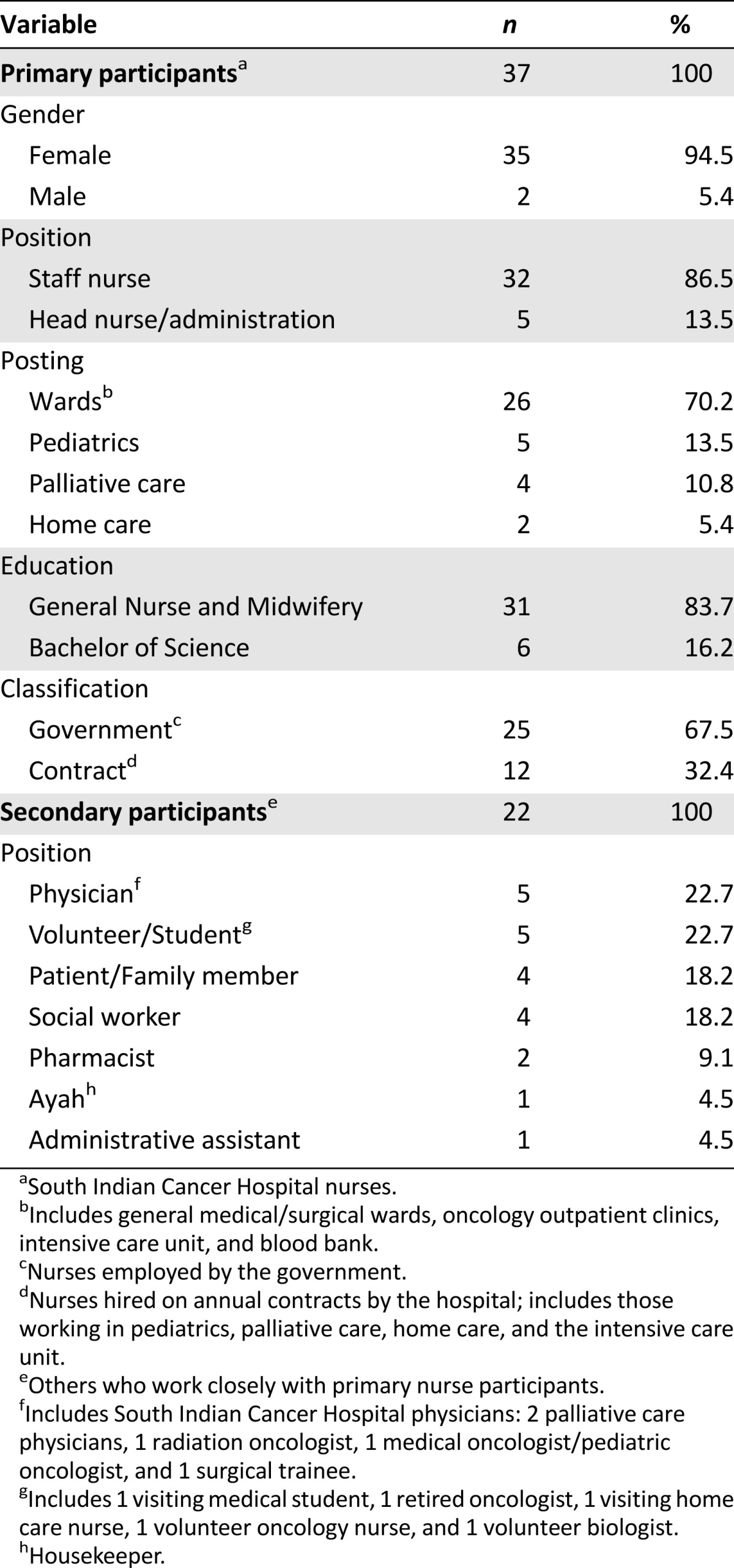

The total sample (n = 59; Table 1) included oncology nurses affiliated with SICH (n = 37) and others who interacted closely with nurses (n = 22).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

Since 2006, SICH has made tremendous progress in ensuring more reliable access to morphine. Yet there are still significant obstacles in obtaining morphine—both at an institution level and in distribution to the individual patient. Morphine is more available at SICH than most of India, but access is largely limited to patients seen by the palliative care service (20% of total patients), and significant gaps in supply still occur. During fieldwork for this study, there were several gaps in oral morphine supply (lasting 3–5 days), but month-long gaps are not uncommon.

Data from field observations and participant interviews revealed that SICH is the only hospital with an adequate, and consistent, supply of morphine in both the entire state and a city of more than 8 million people. With rare exception, morphine (oral and intravenous) was prescribed exclusively by two or three physicians in the palliative care outpatient clinic. Consequently, despite some form of morphine being mostly available in the hospital, the benefits did not reach most patients on the general wards—many of whom suffered in pain without referrals to the palliative care department.

Barrier 1: The Role of Nurses

The majority of nurses had a very limited role in symptom management, and this was a significant factor in how pain was approached. Regular nursing assessments of hospitalized patients were not the norm, and it was generally expected that family caregivers (who were required to be with the patient 24/7 for the patient to be eligible for treatment) would advocate for patients, not nurses. Below, an oncologist (who completed training in the West and then returned to India to practice) describes the difference in the role of the nurse as advocate:

During my residency and my fellowship [abroad] what you see and what you learn is that the nurses are the advocates for the patient. You know, they say the patient has pain, why are we not looking at it? … But here it's not the case, very often. I'm not sure what the reasons are. It might be to do with their training, where they are not sensitized to be sensitive to patients and their symptoms. It might be that there's just too much work for them to do … maybe they just don't have time to ask symptoms, or if they do they don't know what to do with it because there is no solution for the symptom. If a patient tells me at 8:30 in the night that I have pain, what am I going to do about it? It's not much that the nurse can do. If she calls a physician and there's only 1 physician for the 350 patients in the hospital then for him it's not a priority. You know, he's dealing with the shortness of breaths, and the blood transfusions, and the reactions, and this and that, so to somebody with a known history of cancer, terminally ill, with pain, then he's written out “let's wait until tomorrow morning” and the physician has to take care of it. So the evening and night nurses I think they just can't do anything even if there is a symptom. So, maybe they'll stop asking after a point … I feel that they don't even notice that a patient has pain or that they are not moved by it. Have they rationalized it? I don't know. Have they internalized the whole thing and said, “I'm not going to do anything about it … it's not my job to worry about the patient's pain, it's the physician's job?” I don't know.

– HCP 1, physician

General ward nurses did not administer morphine; family members dispensed tablets to the patient if they received prescriptions from the palliative care department. In part, the nurses' lack of engagement with pain assessment and management related to nurse-to-patient ratios that sometimes exceeded 1 nurse for more than 60 patients, negating the ability to provide individualized care. However, there were situations in which the ratios were more favorable (for example, 1 nurse to 4 or 5 patients in the intensive care unit), and ostensibly more personalized care was possible, but significant differences in pain care were not observed during this research. Occasionally, nurses did try to advocate for patients, but oncologists were often reluctant to order morphine:

I'll call the doctor. If he is available, I will say that patient is feeling very restless, he needs some morphine, I will suggest it: “He may need some morphine, sir. He is feeling restless, he is shouting.” If doctor says, “no, no, no not morphine, you give any tramadol injection,” or anything like that, I will give.

– RN 16, general ward nurse

Participants had inconsistent opinions about whether pain management was a nurse’s responsibility. Some nurses felt strongly that doctors were responsible for pain management and felt there was little, if anything, they could do to manage pain. Others felt that pain management was primarily the responsibility of the nurse, recognizing that nurses spent the most time with patients and were more accessible than doctors. A few participants described pain management as an interdisciplinary effort. This acknowledgment of the importance of working together, however, did not always translate into concrete actions to assess and intervene to manage pain. Nurses generally conveyed a sense of helplessness when confronted with difficult pain situations, and common behaviors observed included focusing attention on other duties, such as technical aspects of chemotherapy administration or clerical work.

Barrier 2: Opioid and Pain Management Misperceptions

Many participants related inaccurate information about managing pain (for example, insisting that antinausea or sedative medications were analgesics), and no written protocols, documentation guidelines, or standards of practice were available to help assess and manage pain. Pain on the general wards was typically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as diclofenac), steroids, or tramadol—and if it was deemed severe—a combination of pentazocine and promethazine. Even participants who had some amount of formal palliative care training (n = 18) sometimes verbalized and demonstrated a lack of knowledge about opioids, mostly related to disproportionate fears about addiction, misunderstandings related to appropriate opioid dosing and schedules, and viewing pain as primarily psychological:

In my experience, there was one patient she used to come [daily] and ask us to give the pain injection, regularly. For a long period. Then I tried placebo. Giving some sweet water to that patient. And she didn't complain … I felt good. I was able to understand the psychology of the patient. She was becoming dependent. She feels that by taking the injection she won't have pain. So, we tried that and the patient was quite good.

– RN 1, general ward nurse

There was a prevalent attitude that cancer pain was inevitable and largely unmanageable. Witnessing patients suffering in unrelieved pain seemed to reinforce this belief. Some nurses felt that even morphine was ineffective in treating cancer pain, as they viewed opioid side effects as offsetting any benefit:

In the last stages, when the patient is in a lot of pain, we have Pain and Palliative Care here; we send them there. Even if they receive the morphine dose, the pain does not come down. It does not come down even after giving them pain killers. We cannot do anything then. We say it will come down, but it doesn't … and also, if they use more morphine, they will have constipation. The constipation is not relieved even after giving Dulcolax (bisacodyl).

– RN 24, general ward nurse

Often during fieldwork patients were observed clearly suffering in pain, but participants did not seem to “see” the same reality; obvious pain from massive malignant wounds or recent surgery was dismissed as not a problem, or attributed to psychological causes. Patients and family members also demonstrated a lack of knowledge about pain management. Throughout the hospital, the majority of patients and family members verbalized a very limited understanding of the medications they were taking for pain, even those on morphine. Most reported they simply followed the doctor’s instructions to “take these tablets for pain.”

Barrier 3: Bureaucratic Hurdles

During fieldwork, it was discovered that the nitty-gritty details that made it possible for morphine to be stocked at SICH hinged on one (nonmedical) individual, who had taken it up as her personal responsibility to help ensure that the hospital had an adequate supply of morphine:

So, again it's paperwork. Again, going to the Director, “sir, the transport permit is ready, we need to procure the drug, please kindly make the advanced payment.” Director signs one letter and from the in-charge of the department we get one letter to make the necessary arrangements for advance payment and again that copy should go to the purchase section, from there the purchase section to the billing department, again from the billing department, to the accountant and then accountant settles the money, after doing his own format, he will have some work to do, to arrange for payment with the Director … But again if you depend for this dispatch thing from the hospital, they say very silly reasons saying that we don't have envelope covers, or we don't have revenue stamps or some stamps to attach, so today this dispatch guy didn't come, so this person did not come, who will go and post it and come? So again it takes another 3, 4 days or 1 week delay … And then finally, they send the drug. So because it's a big parcel it takes minimum 1 week to 10 days to reach us… finally our stock is ready in the pharmacy. And even though our stock is ready in the Pharmacy, we can't just like that open the stock and use it. Again there's a process. We have to call the Drug Inspector who has come and make the report initially and submit it to the Director of Drug Controller, he should come, we should call him, he will not be available on the phone, he will not take the calls, and we should call him repeatedly, one week, minimum 3 to 4 days we have to call him. Once it took 15 days also, we have stock in the hospital and we are unable to open the stock and use it.

– HCP 18, administrator

Bureaucratic delays in dispensing morphine, even after it was procured and physically available in the hospital, could result in significant patient distress and unmanaged pain:

Right now, it [morphine] has come, but the Drug Inspector has to come and open [the package] and then we will distribute. Today is the 3rd day, Friday, Saturday, and Monday; 3 days gap. Patients came. I told to the patients, “wait till Monday or you can take weak opioid… and you can take steroid … and then we will write for Voveran (diclofenac) and Rantac (ranitidine)”… Sometimes, they beg from other people that are rich in their family, because, [they say] “without this tablet, I cannot reduce my pain, I can't reduce my breathlessness, I can't reduce my cough.” Sometimes, [the gap in supply] may be 1 month, then it is very terrible job to handle the patients.

– RN 7, palliative care nurse

Members of the palliative care team expressed frustration and acknowledged the difficulty for patients when the morphine supply ran out, especially for patients who traveled long distances to reach the hospital. Consequently, staff developed “work-arounds,” such as keeping a separate, additional supply of morphine tablets to administer if the hospital pharmacy stock was depleted, or using steroids or tramadol until morphine was again available. In particularly dire times, both the hospital supply and the extra supply would run out. In these cases, patients would try to obtain morphine from another hospital—a burdensome, costly, and sometimes impossible task.

Barrier 4: Sociocultural and Infrastructure Challenges

The typical SICH patient was financially destitute, illiterate, suffering from metastatic disease, and had traveled hundreds of kilometers to seek care. Patients seen by the palliative care department were generally given a month’s supply of morphine, but a family member had to return to the city regularly to obtain refills as there was no mechanism to procure morphine in rural areas. Sometimes, a family member would travel long distances from the patient’s village to SICH only to discover that morphine was unavailable. In these cases, patients and family members were referred to other local hospital pharmacies, known to sometimes stock a small supply of morphine. This was still problematic, however, as many patients could not afford to pay for transportation from SICH to another local hospital. Bandhs (strikes) made transportation even more challenging, and other hospitals were often reluctant to dispense their limited (if any) supply of morphine tablets to patients from SICH.

Discussion

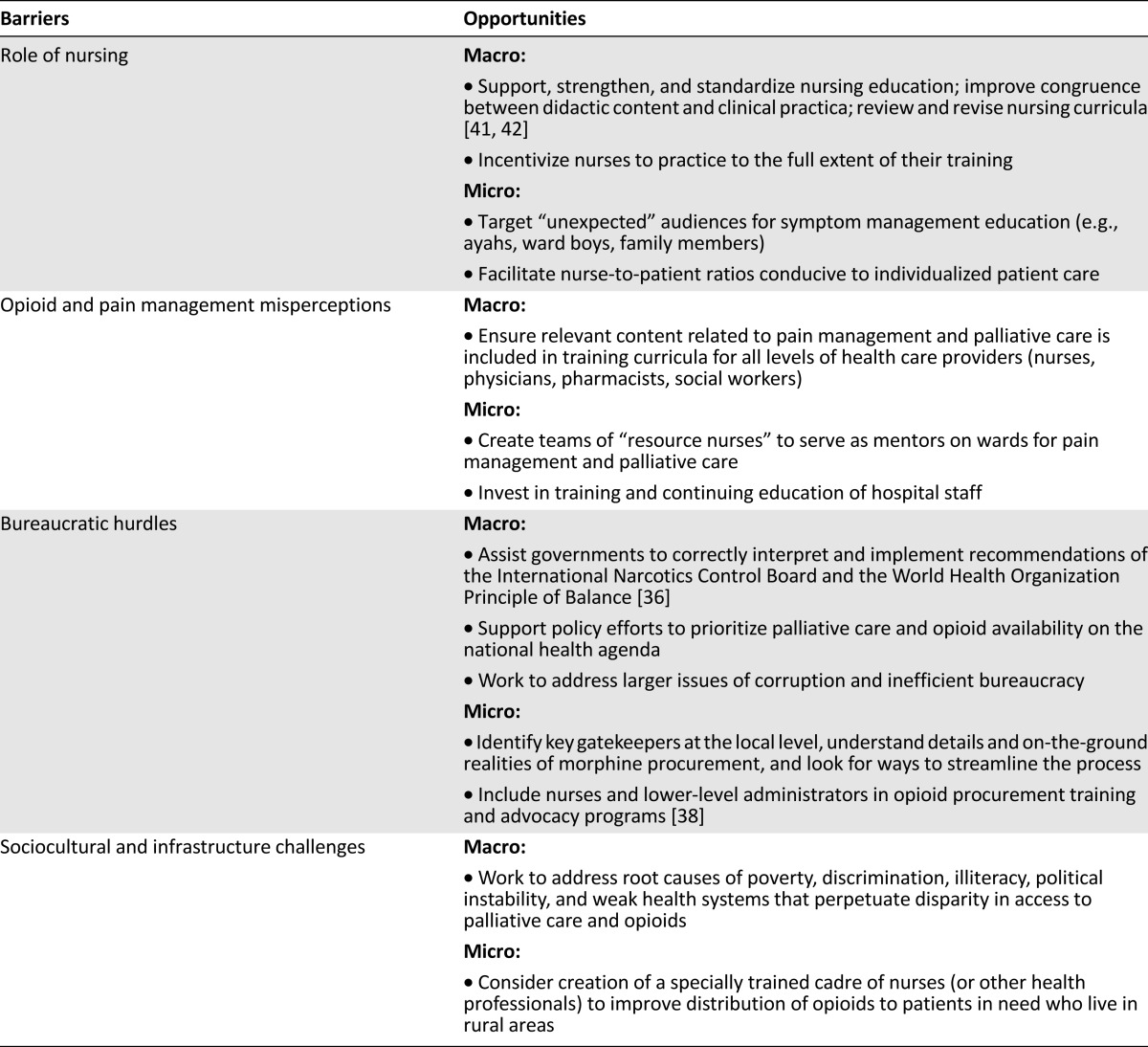

This study confirms known barriers to cancer pain management in LMICs related to knowledge deficits, regulatory obstacles, and infrastructure/sociocultural challenges [3, 13–15, 25–29] and enhances our understanding of these challenges in two key ways: one, by more thoroughly exploring the role of bedside nurses in managing pain in this context; and two, by providing additional insight into the logistical details involved with morphine procurement. This study also highlights the importance of both macro (state and national)- and micro (regional and local)-level policy and practice changes that are needed to enhance cancer pain management in settings such as SICH (Table 2).

Table 2.

Barriers and opportunities to improve cancer pain management in India

Traditionally, oncology nurses are viewed as front-line care providers responsible for pain assessment and management [30]. However, complex practical, sociocultural, and political factors seemed to influence the willingness, or ability, of the nurse to take an active role in pain assessment and management at SICH; similar issues have been described elsewhere [21, 31]. Consistent with findings from other lower income countries, nurses at SICH did not routinely or systematically assess or ask patients about pain [15, 25, 32, 33] and relied upon the patients or family attendants (members) to advocate, and manage, pain for themselves. A culture of nonintervention related to pain [15] was the norm throughout most of SICH, particularly on the general wards. The reasons for this are complex and seem to involve not only limited resources and training but deeply embedded sociocultural dynamics that exist between patient and provider [21, 31].

Even when morphine is available, training and education are essential elements in improving cancer pain management. In any setting, it makes little difference if morphine is available if practitioners will not prescribe it, nurses will not administer it, and patients will not take it. Educational programs must account for sociocultural factors such as when and why and how practitioners will, or will not, advocate for patients in pain, how they view the experience of cancer pain for their patients (as something bad to be eradicated or prevented, or something to be endured, perhaps by those who are deserving), and what they see as their ethical and moral obligation in treating cancer pain. It is essential that country-level medical and nursing school curricula, attuned to these crucial sociocultural factors, include content related to palliative care and cancer pain management.

Given the scope of nursing practice observed by V.L. in this study, it is likely not currently feasible—or advisable—for the majority of general ward nurses to administer morphine to patients. However, working toward this should be a long-term goal, as it would allow for a much greater number of patients to receive optimal pain management. One potential approach is to identify and train a group of motivated oncology nurses and formally recognize them as palliative care resource nurses who can serve as mentors on the ward. Similar approaches have been used in higher-resource settings [34] and may have applicability in LMICs with contextual adaptations.

Other nontraditional care providers could also benefit from training related to pain assessment and management, as also suggested by Size et al. [15]. For example, in SICH ayahs (housekeepers), ward boys (orderlies) and especially family members played a vital role in managing pain; their potential contributions should be recognized and supported. Piloting educational interventions to help family attendants learn medication regimens, how to communicate their assessments of pain to nurses and physicians, and how to safely administer morphine is a next step forward in LMIC institutions in which morphine may be available, and prescribed, but general staff may not yet be fully engaged in pain assessment and management.

Ensuring morphine availability also requires working to remove barriers that impact the distribution system [35]. On a macro-level this involves helping governments correctly interpret and implement international drug control requirements so they effectively balance preventing diversion of controlled substances with ensuring their availability for legitimate medical purposes [13, 36], supporting policy efforts to make palliative care and morphine availability a priority on the national health agenda, and working to address larger societal issues, such as corruption, complicated bureaucracy, and geographical barriers. On a micro-level, utilizing quality improvement approaches to deconstruct the process of morphine procurement and engaging key gatekeepers (such as the drug controller who must inspect incoming supplies of morphine before it can be dispensed, or the accountant who must process the advance payment to obtain the transport permit) are vital to improve opioid availability and use in LMICs. The very recent amendment of the onerous Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act by the Indian parliament holds great promise in removing many of the regulatory barriers related to opioid availability [37]. However, time and effort are needed to ensure its effective implementation.

Opioid procurement training and advocacy programs, such as those offered by the Pain and Policy Studies Group [38] traditionally have involved physicians, pharmacists, and high-ranking government officials. These successful programs should also consider involving nurses and lower-level administrators who are likely to play crucial roles in the details of morphine procurement and in ensuring that the supply reaches patients on the wards.

The broader sociocultural challenges that affect hospitals like SICH, such as poverty, illiteracy, and political instability, are substantive and lack simple solutions. One approach is to take feasible steps to improve access to opioids for patients most in need, working within the existing infrastructure. For example, more than 72% of the Indian population lives in villages [17], and these individuals are at particular risk of dying in pain as a result of lack of access to morphine. Serious consideration should be given to creating a specially trained cadre of nurses to help improve distribution of morphine among rural patients in India. Such programs could look to successful African models [39] and be piloted in a state with an existing palliative care network and a strong history of advocacy and policy work related to opioid availability, such as Kerala or Andhra Pradesh/Telangana [16, 17, 40].

Limitations

Language barriers sometimes resulted in translation problems or misunderstandings; every effort was made to clarify discrepancies. The study sample was skewed toward an experienced group of government nurses, whose observed actions were not always congruent with what they expressed during interviews. This inconsistency may have been related, in part, to social desirability bias. Many participants volunteered that SICH is a “typical” government institution, suggesting generalizability to other government hospitals in India. However, SICH is unique in regard to its palliative care department and efforts made to procure morphine; the majority of government hospitals in India have not made the same progress in these areas [16–18].

Conclusion

For many patients suffering with terminal cancer in LMICs, morphine is often the only effective therapy that can be offered. Ensuring that patients who desperately need morphine have access to this medication is critical as the global cancer burden continues to grow. Interventions that account for the role and attitudes of health care providers, target unexpected audiences for symptom management education, work within the existing sociocultural infrastructure, and focus on process improvement related to morphine procurement are important next steps in future research and policy work.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the entire staff, and particularly the nurses, at South Indian Cancer Hospital (SICH) who welcomed us into their community of care and shared their stories and experiences. We are also thankful to the Government of India for allowing this research to be conducted; the Fulbright-Nehru Program and the International Network for Cancer Treatment and Research for facilitating the fieldwork; Vineela Rapelli for her invaluable support as research assistant; and Patricia Berry, Kristin Cloyes (University of Utah, College of Nursing), Mark Nichter (University of Arizona, School of Anthropology), Felicia Knaul (Harvard Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University), Laura Hayman (University of Massachusetts, Boston, College of Nursing and Health Sciences), and Donna Berry (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Phyllis F. Cantor Center) for their generous mentorship. This work was supported by American Cancer Society Grants 117214-DSCN-09-141-01-SCN and 121673-DSCNR-09-141-03-SCN; the Fulbright Program; the University of Utah Graduate School; and the National Cancer Institute, U54 Cancer and Health Disparities.

Abstracts related to this manuscript were presented as posters at the Global Health and Innovation Conference at Yale University, April 12–13, 2014, and at the Global Cancer Care: Challenges and Opportunities Symposium at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, February 8, 2014. The first author is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard Medical School and engages in collaborative research with the Harvard Global Equity Initiative.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Virginia LeBaron, Susan L. Beck, Martha Maurer, Fraser Black

Provision of study material or patients: Gayatri Palat

Collection and/or assembly of data: Virginia LeBaron, Susan L. Beck, Gayatri Palat

Data analysis and interpretation: Virginia LeBaron, Susan L. Beck, Martha Maurer, Fraser Black

Manuscript writing: Virginia LeBaron, Susan L. Beck, Martha Maurer, Fraser Black

Final approval of manuscript: Virginia LeBaron, Susan L. Beck, Martha Maurer, Fraser Black, Gayatri Palat

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Human Rights Watch. Global State of Pain treatment: Access to Palliative Care as a Human Right, 2011. Available at http://www.hwr.org Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 2.World Health Organization. World Health Organization Cancer Control Programme, 2012. Available at http://www.who.int/cancer/en/ Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 3. Closing the Cancer Divide: An Equity Imperative. Knaul FM, Gralow JR, Atun R et al., eds. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Lima L, Krakauer EL, Lorenz K, et al. Ensuring palliative medicine availability: The development of the IAHPC list of essential medicines for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Atomic Energy Agency. Fighting Cancer in the Developing World, 2012. Available at http://cancer.iaea.org/documents/PACTBrochure.pdf Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 6.Silberner J. Cancer's New Battleground - The Developing World; Part V: Dispensing Comfort, 2012. Available at http://www.theworld.org/cancer-new-battleground Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 7.World Health Organization. Essential Medications, 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/topics/essential_medicines/en/ Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 8.Brennan F, Carr DB, Cousins M. Pain management: A fundamental human right. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:205–221. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268145.52345.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Human Rights Watch. Unbearable Pain: India's Obligation to Ensure Palliative Care, 2009. Available at http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/health1009web.pdf Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 10.Lohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ. Access to pain treatment as a human right. BMC Med. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nickerson JW, Attaran A. The inadequate treatment of pain: Collateral damage from the war on drugs. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations . Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, as Amended by the 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. New York, NY: United Nations: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurer MA, Gilson AM, Husain SA, et al. Examining influences on the availability of and access to opioids for pain management and palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2013;27:255–260. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2013.816407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Maurer M. Opioid policy, availability, and access in developing and non-industrialized countries. In: Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP, editors. Bonica's Management of Pain. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Size M, Soyannwo OA, Justins DM. Pain management in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(suppl 1):38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDermott E, Selman L, Wright M, et al. Hospice and palliative care development in India: A multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palat G, Venkateswaran C. Progress of palliative care in India. Progress in Palliative Care. 2012;20:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajagopal MR, Venkateswaran C. Palliative care in India: Successes and limitations. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17:121–128; discussion 129–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajagopal MR, Joranson DE. India: Opioid availability. An update. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:149–154. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.105683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeBaron V. Exploring the Relationship between Nurse Moral Distress and Cancer Pain Management: A Critical Ethnography of Oncology Nurses in India: College of Nursing. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeBaron V, Beck S, Black F, et al. Exploring the relationship between moral distress and opioid availability: An ethnography of cancer nurses in India. Cancer Nurs. 2013 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macpherson C, Aarons D. Overcoming barriers to pain relief in the Caribbean. Dev World Bioeth. 2009;9:99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2009.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livingston J. The next epidemic: Pain and the politics of relief in Botswana's cancer ward. In: Biehl J, Petryna A, editors. When People Come First: Critical Studies in Global Health. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2013. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Silva BSS, Rolls C. Attitudes, beliefs, and practices of Sri Lankan nurses toward cancer pain management: An ethnographic study. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:419–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck SL, Falkson G. Prevalence and management of cancer pain in South Africa. Pain. 2001;94:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00343-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck SL. An ethnographic study of factors influencing cancer pain management in South Africa. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:91–99; quiz 99–100. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oncology Nursing Society Cancer pain management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:817–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair S, Healey M. A Profession on the Margins: Status Issues in Indian Nursing. Centre for Women's Development Studies, Occasion Paper, 2006. Available at http://www.cwds.ac.in/ocpaper/profession_on_the_margins.pdf Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 32.De Silva BSS, Rolls C. Health-care system and nursing in Sri Lanka: An ethnography study. Nurs Health Sci. 2010;12:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew PJ, Mathew JL, Singhi S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of pediatric critical care nurses towards pain: Survey in a developing country setting. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:196–200. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.85203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeBaron VT, Bohnenkamp SK, Reed PG. A community partnership approach to building and empowering a palliative care resource nurse team. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namukwaya E, Leng M, Downing J, et al. Cancer pain management in resource-limited settings: A practice review. Pain Res Treat. 2011;2011:393404. doi: 10.1155/2011/393404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization Policy Guidelines Ensuring Balance in National Policies on Controlled Substances, Guidance for Availability and Accessibility for Controlled Medicines, 2011. Available at http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/guide_nocp_sanend/en/ Accessed December 1, 2013.

- 37.Passage of the Narcotic Drug and Psychotropic Substances Amendment, White Paper. Available at: http://www.egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2014/158504.pdf Accessed March 28, 2014.

- 38.Bosnjak S, Maurer MA, Ryan KM, et al. Improving the availability and accessibility of opioids for the treatment of pain: The International Pain Policy Fellowship. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Livingstone H. Pain relief in the developing world: The experience of hospice Africa-Uganda. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17:107–118; discussion 119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajagopal MR, Palat G. Kerala, India: Status of cancer pain relief and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:191–193. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans C, Razia R, Cook E. Building nurse education capacity in India: Insights from a faculty development programme in Andhra Pradesh. BMC Nurs. 2013;12:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhaumik S. Can India end the corruption in nurses’ training? BMJ. 2013;347:f6881. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]