Abstract

Native Mandarin normal-hearing (NH) listeners can easily perceive lexical tones even under conditions of great voice pitch variations across speakers by using the pitch contrast between context and target stimuli. It is however unclear whether cochlear implant (CI) users with limited access to pitch cues can make similar use of context pitch cues for tone normalization. In this study, native Mandarin NH listeners and pre-lingually deafened unilaterally implanted CI users were asked to recognize a series of Mandarin tones varying from Tone 1 (high-flat) to Tone 2 (mid-rising) with or without a preceding sentence context. Most of the CI subjects used a hearing aid (HA) in the non-implanted ear (i.e., bimodal users) and were tested both with CI alone and CI+HA. In the test without context, typical S-shaped tone recognition functions were observed for most CI subjects and the function slopes and perceptual boundaries were similar with either CI alone or CI+HA. Compared to NH subjects, CI subjects were less sensitive to the pitch changes in target tones. In the test with context, NH subjects had more (resp. fewer) Tone-2 responses in a context with high (resp. low) fundamental frequencies, known as the contrastive context effect. For CI subjects, a similar contrastive context effect was found statistically significant for tone recognition with CI+HA but not with CI alone. The results suggest that the pitch cues from CIs may not be sufficient to consistently support the pitch contrast processing for tone normalization. The additional pitch cues from aided residual acoustic hearing can however provide CI users with a similar tone normalization capability as NH listeners.

Keywords: cochlear implants, tone normalization, context effects, bimodal hearing

1. Introduction1

In Mandarin Chinese, tones, just like consonants and vowels, carry lexical meanings. The four Mandarin tones are primarily characterized by different pitch levels and contours (Tone 1: high-flat, Tone 2: mid-rising, Tone 3: low-falling-rising, and Tone 4: high-falling; e.g., Chao, 1948). Tonal information is important for Mandarin speech recognition especially in noise (e.g., Chen et al., 2013) because there are many Mandarin words that differ only by tone. For example, the syllable /yi/ can mean ‘cloth’ in Tone 1, ‘aunt’ in Tone 2, ‘already’ in Tone 3, and ‘easy’ in Tone 4. Mandarin tone recognition involves a sophisticated process because the pitch cues to tones vary greatly across speakers with different voice characteristics such as the fundamental frequency or F0 (the most significant acoustic correlate of pitch). For example, a high-F0 tone (e.g., Tone 2) produced by a low-F0 male speaker may have similar F0s as a low-F0 tone (e.g., Tone 3) produced by a high-F0 female speaker. Normal-hearing (NH) listeners can recognize Mandarin tones effortlessly even across multiple speakers, possibly using a perceptual mechanism that normalizes the pitch differences across speakers and preserves perceptual constancy of lexical tones (e.g., Moore and Jongman, 1997; Huang and Holt, 2009).

Pitch cues in the preceding context may be used to adjust target tone recognition and achieve tone normalization. Earlier studies (e.g., Leather, 1983; Fox and Qi, 1990) however reported a weak dependence of Mandarin tone recognition of NH listeners on context pitch cues. In their experimental settings, Fox and Qi (1990) tested the recognition of a Tone 1-Tone 2 series that varied only in onset F0 with a preceding context being either Tone 1 or Tone 2. Note that the Tone-2 context may have provided the necessary F0 range for listeners to compare with the onset F0s of the target tones throughout the test, resulting in the conclusion of no context effect on Mandarin tone recognition. More recently, Moore and Jongman (1997) and Huang and Holt (2009) both found that, with carefully designed context stimuli (e.g., a natural preceding sentence produced by either a high- or a low-F0 speaker), NH listeners used context pitch cues to shape their recognition of Mandarin contour tones (e.g., a Tone 2-Tone 3 series) and had more (resp. fewer) low-tone responses (e.g., Tone 3) in a high-F0 (resp. low-F0) context. This suggests a contrastive context effect on Mandarin tone recognition.

Previous studies with NH listeners have also considered the potential mechanisms of tone normalization or context-dependent tone recognition. Moore and Jongman (1997) attributed the contrastive context effect to a speaker-contingent process in which listeners may have used the context pitch cues to identify the speaker and then calibrated target tone recognition based on the perceived speaker identity. However, tone normalization may also be associated with a general auditory process in which the mean pitch level of the preceding sentence may have exerted a contrastive influence on the perception of the target pitch level, independent of the perceived speaker identity. The hypothesis of a general auditory mechanism for tone normalization was supported by Huang and Holt (2009). They found that non-speech contexts consisting of harmonic complex tones or pure tones had a similar contrastive effect on target tone recognition as speech contexts. This suggests that tone normalization may not require speaker, articulatory, or phonetic information in the context. In a follow-up study, Huang and Holt (2011) found that tone recognition was also contrastively affected by speech contexts with the F0 removed by high-pass filtering and masked by low-frequency noise. This suggests that central, instead of peripheral, auditory processing may be responsible for tone normalization, because the pitch of the missing-F0 context was thought to be derived from the harmonic templates at a central level beyond the cochlea (e.g., Yost, 2009).

Cochlear implants (CIs) bypass the dysfunctional cochlea and directly stimulate the surviving auditory nerves using electric pulses to partially restore hearing sensation to profoundly deaf people. Current CIs use 12–22 electrodes to encode temporal envelope cues of incoming sounds in different frequency bands, providing most CI users with good speech recognition in quiet. However, the small number of electrodes and the large current spread of electric stimulation have prevented CIs from resolving both the F0 and the harmonics of incoming sounds that carry spectral cues for pitch perception in NH listeners. On the other hand, weak temporal cues to pitch may be available from the pulse amplitude modulations at the F0 on individual electrodes (e.g., Geurts and Wouters, 2001; Green et al., 2002). Despite this, CI users’ sensitivity to temporal pitch cues is greatly reduced as the F0 increases (e.g., Zeng, 2002). Although amplitude envelope and vowel duration cues may partially compensate for the limited pitch cues to Mandarin tones (e.g., Fu et al., 1998; Luo and Fu, 2004), Mandarin tone recognition is still much more challenging in CI users than in NH listeners (e.g., Luo et al., 2008; Han et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013).

With the CI candidacy criteria expanded nowadays, an increased percentage of the CI population has some residual low-frequency acoustic hearing and chooses to wear a hearing aid (HA) in the non-implanted ear. In the binaural bimodal fitting (i.e., CI+HA) condition, acoustic hearing from the HA may be integrated with electric hearing from the CI to yield improved speech recognition in noise as compared to the CI or HA alone condition (e.g., Kong et al., 2005; Dorman et al., 2008). The bimodal benefits in noise may be associated with a mechanism in which residual low-frequency acoustic hearing provides fine-grained pitch cues for CI users to better segregate speech from noise based on the pitch differences between target talkers and the background noise (e.g., Turner et al., 2004; Kong et al., 2005). The contribution of the pitch cues from residual low-frequency acoustic hearing to improved Mandarin tone recognition with CIs was verified in a simulation study (Luo et al., 2006). It is however previously unexamined whether there are bimodal benefits to tone recognition in real Mandarin-speaking CI users.

Previous studies with CI users (e.g., Luo et al., 2008; Han et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013) have only tested isolated Mandarin tone recognition without context. It is unclear whether CI users are able to use context pitch cues to handle talker variability in voice pitch and achieve tone normalization in everyday situations with continuous speech. We hypothesized that the central pitch contrast processing for tone normalization (Huang and Holt, 2011) may not be effective with CI alone due to the inadequate pitch cues. With bimodal fitting or CI+HA, the pitch cues from residual acoustic hearing may not only improve tone recognition without context but also elicit stronger context effects on tone recognition. To test these hypotheses, a similar design as Huang and Holt (2009) was adopted to test tone recognition with or without context in pre-lingually deafened native Mandarin CI users (ranging in age from preteens to young adults) with either CI alone or CI+HA. CI users were also compared with native Mandarin NH listeners (young adults) to examine whether a similar contrastive context effect in NH listeners’ tone recognition (e.g., Huang and Holt, 2009) will also be observed in CI users’ tone recognition, even though the CI group was younger than the NH group. Studies have shown that the general auditory mechanism for context effects in phoneme recognition is available even in NH infants or children with limited cognitive capacity, memory resources, and language experience (Fowler et al., 1990; Hufnagle et al., 2013).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Ten native Mandarin NH listeners (five females and five males aged between 22 and 33 years with an average age of 26 years) were recruited from the Purdue University community as the control group. All NH subjects had hearing thresholds below 25 dB HL at octaves between 0.25 and 8 kHz in both ears. Fifteen native Mandarin CI users (seven females and eight males aged between 10 and 20 years with an average age of 15 years) were recruited from the patient population of the Children’s Hearing Foundation in Taiwan. CI subject demographics including their CI and HA details are listed in Table 1. These CI subjects were all pre-lingually deafened and have been using their implant for more than one year. Before implantation, all CI subjects except S6 wore bilateral HAs and received auditory-verbal therapy from the Children’s Hearing Foundation. After implantation, most CI subjects continued to wear an HA in the non-implanted ear (i.e., bimodal users) except S3, S4, S6, S7, and S13. Among those who used CI alone, S7 had hearing fluctuation due to enlarged vestibular aqueduct (EVA), while the others had no usable residual hearing in the non-implanted ear. Table 2 lists the unaided and aided hearing thresholds for each CI subject’s non-implanted ear. The unaided audiograms mostly showed a moderately severe sloping to profound hearing loss, while the aided thresholds were mostly within the range of mild to moderate hearing loss for frequencies up to 2 kHz. This study was reviewed and approved by the local IRB committees. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the parents of CI subjects who were under 18 years old. All subjects were compensated for their participation in this study.

Table 1.

CI subject demographics and details of CI and HA use.

| Subject | Age (yrs) | Gender | Etiology | Implant (ear) | Strategy | Duration of CI use (yrs) |

Hearing aid | Test condition CI alone CI+HA |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 13 | F | Unknown | Freedom (R) | ACE | 4 | Phonak Naida III UP | X | |

| S2 | 17 | M | EVA | Freedom (L) | ACE | 5 | Phonak Supero 412 | X | X |

| S3 | 17 | M | EVA | Nucleus 24M (R) | ACE | 14 | N/A | X | |

| S4 | 19 | M | EVA | Freedom (R) | ACE | 3 | N/A | X | |

| S5 | 20 | M | EVA | Nucleus 24M (R) | ACE | 11 | C18+ | X | X |

| S6 | 16 | F | Meningitis | Nucleus 24M (L) | ACE | 15 | N/A | X | |

| S7 | 13 | F | EVA | Harmony (R) | HiRes-120 | 1 | N/A | X | |

| S8 | 16 | M | Unknown | Freedom (L) | ACE | 4 | Phonak Naida III UP | X | |

| S9 | 20 | F | Unknown | Freedom (R) | ACE | 3 | Starkey Destiny 1200 P+ | X | X |

| S10 | 20 | M | Unknown | Freedom (L) | ACE | 5 | Phonak Naida III UP | X | |

| S11 | 12 | F | Heredity | Freedom (L) | ACE | 3 | Targa 3 HP | X | X |

| S12 | 11 | M | EVA | Freedom (L) | ACE | 1 | Widex B32 | X | X |

| S13 | 10 | F | Unknown | Nucleus 24CS (L) | ACE | 2 | N/A | X | |

| S14 | 14 | F | Unknown | Nucleus 24CS (L) | ACE | 10 | Phonak Savia Art 411 | X | X |

| S15 | 11 | M | High fever | Freedom (R) | ACE | 6 | Oticon Sumo DM | X | X |

EVA: Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct; ACE: Advanced Combination Encoder. N/A: not available.

Table 2.

Unaided and aided hearing thresholds in the non-implanted 1 ear of CI subjects.

| Subject | Unaided thresholds of the non-implanted ear (dB HL) | Aided thresholds with hearing aid (dB HL) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 kHz | 0.5 kHz | 1 kHz | 2 kHz | 4 kHz | 6 kHz | 0.25 kHz | 0.5 kHz | 1 kHz | 2 kHz | 4 kHz | 6 kHz | |

| S1 | 100 | 100 | 105 | 115 | NR | NR | 30 | 30 | 25 | 60 | NR | NR |

| S2 | 85 | 90 | 95 | 100 | 115 | NR | 45 | 40 | 40 | 35 | 60 | 70 |

| S3 | 90 | 100 | 105 | 100 | 110 | 115 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| S4 | 70 | 75 | 110 | 115 | 115 | DNT | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| S5 | 65 | 60 | 85 | NR | NR | DNT | 40 | 30 | 45 | NR | DNT | DNT |

| S6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| S7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| S8 | 85 | 90 | 100 | 110 | NR | NR | 35 | 25 | 25 | 35 | 65 | 65 |

| S9 | 85 | 85 | 95 | 105 | NR | DNT | 35 | 25 | 30 | 50 | 70 | NR |

| S10 | 85 | 90 | 100 | 110 | NR | DNT | 30 | 25 | 30 | 40 | NR | NR |

| S11 | 85 | 90 | 100 | 110 | NR | NR | 30 | 35 | 35 | 50 | NR | DNT |

| S12 | 65 | 80 | 75 | 90 | 100 | DNT | 30 | 35 | 35 | 35 | 50 | DNT |

| S13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| S14 | NR | 100 | 100 | 110 | 115 | 105 | 65 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 55 | DNT |

| S15 | 70 | 80 | 95 | 105 | 115 | NR | 35 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 60 | 75 |

NR: no response; DNT: did not test; N/A: not available.

A tone recognition test (Luo et al., 2008) was used to measure CI subjects’ ability to recognize naturally produced Mandarin tones in isolation. We hypothesized that CI subjects’ natural tone recognition performance is positively correlated with their ability to recognize the synthesized Tone 1-Tone 2 series and use context pitch cues for tone normalization in the experiment. Six Mandarin syllables (/a/, /o/, /e/, /yi/, /wu/, and /yü/) produced with four lexical tones by two male and two female speakers (different from the female speaker used in the experiment) were tested in random order. Subjects identified the four tones by clicking on response buttons shown on a computer screen. The response time between stimulus offset and button click was recorded. The natural tone recognition test was conducted before the experiment. All CI subjects except S1 were tested with CI alone and all bimodal users were also tested with CI+HA. The two conditions were tested in a counterbalanced order between bimodal users. The natural tone recognition scores and the total response time of the two test conditions are listed in Table 3 for reference.

Table 3.

Percent correct scores and total response time for natural Mandarin tone recognition 1 of CI subjects.

| Subject | Tone recognition (%) | Response time (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI alone | CI+HA | CI alone | CI+HA | |

| S1 | N/A | 68.23 | N/A | 253.24 |

| S2 | 80.21 | 86.98 | 252.14 | 249.63 |

| S3 | 73.44 | N/A | 228.25 | N/A |

| S4 | 65.63 | N/A | 325.53 | N/A |

| S5 | 76.56 | 93.75 | 337.85 | 219.45 |

| S6 | 54.69 | N/A | 226.03 | N/A |

| S7 | 75.00 | N/A | 326.02 | N/A |

| S8 | 67.71 | 64.59 | 343.11 | 236.19 |

| S9 | 64.58 | 63.02 | 359.47 | 293.15 |

| S10 | 61.46 | 70.32 | 264.21 | 219.21 |

| S11 | 67.70 | 78.13 | 285.37 | 260.04 |

| S12 | 56.25 | 76.04 | 391.82 | 296.20 |

| S13 | 46.87 | N/A | 417.81 | N/A |

| S14 | 74.48 | 78.13 | 226.11 | 256.50 |

| S15 | 71.35 | 71.36 | 276.25 | 289.46 |

N/A: not available.

2.2. Stimuli

A pilot study suggested that with CI alone, CI users may not be able to reliably identify even the most rising pitch contours tested in previous studies of NH listeners’ tone normalization (e.g., Huang and Holt, 2009), where the F0 range of a male speaker was used. To accommodate the poor pitch perception associated with CIs, stimuli in this study were produced by a female native Mandarin speaker. In the Tone-2 utterances of the female speaker, the F0 increased from 160 to 300 Hz, providing a larger F0 range for testing. All stimuli were recorded at a 44100-Hz sampling rate with 16-bit resolution.

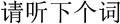

The Mandarin syllable /yi/ meaning ‘cloth’ in Tone 1 and ‘aunt’ in Tone 2 was selected as the target syllable. A 380-ms /yi/ token produced with Tone 1 was modified to have different F0 contours using PRAAT 5.3.17 (Boersma and Weenink, 2012). In each contour, the F0 linearly transitioned from its onset (ranging from 160 to 300 Hz in 20-Hz steps) to its offset (fixed at 300 Hz). Thus, there was a series of eight target tones that varied acoustically in onset F0 and perceptually from Tone 1 to Tone 2. The preceding context was a semantically neutral Mandarin sentence  /qing3 ting1 xia4 ge4 ci2/ (please listen to the next word) with all four Mandarin tones. The originally recorded 1336-ms sentence had an F0 range from 154 to 337 Hz with a mean F0 of 224 Hz. A high-F0 context with a mean F0 of 300 Hz and a low-F0 context with a mean F0 of 160 Hz were created by shifting up and down the entire F0 contour of the sentence, respectively. The F0 contour was modified using PRAAT 5.3.17 (Boersma and Weenink, 2012). Note that the two mean F0s of the context corresponded to the highest and lowest onset F0s of the target stimuli. Matched in root mean square (RMS) level, each target stimulus was concatenated with each context stimulus with an inter-stimulus interval of 50 ms to test tone recognition with context. Figure 1 shows the F0 contours of different context and target stimuli.

/qing3 ting1 xia4 ge4 ci2/ (please listen to the next word) with all four Mandarin tones. The originally recorded 1336-ms sentence had an F0 range from 154 to 337 Hz with a mean F0 of 224 Hz. A high-F0 context with a mean F0 of 300 Hz and a low-F0 context with a mean F0 of 160 Hz were created by shifting up and down the entire F0 contour of the sentence, respectively. The F0 contour was modified using PRAAT 5.3.17 (Boersma and Weenink, 2012). Note that the two mean F0s of the context corresponded to the highest and lowest onset F0s of the target stimuli. Matched in root mean square (RMS) level, each target stimulus was concatenated with each context stimulus with an inter-stimulus interval of 50 ms to test tone recognition with context. Figure 1 shows the F0 contours of different context and target stimuli.

Fig. 1.

Fundamental frequency (F0) contours of the low-F0 context (dashed lines), high-F0 context (dashed-dotted lines), and target Tone 1-Tone 2 series (solid lines).

2.3. Procedures

NH subjects were tested in a double-walled, sound-treated booth at the Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. Stimuli were presented at 65 dBA via the basic loudspeaker of a GSI-61 audiometer placed about half a meter in front of the subject. CI users were tested in a sound-treated therapy room at the Children’s Hearing Foundation in Taiwan. Stimuli were presented at each CI subject’s most comfortable level (ranging from 60 to 70 dBA) via a single loudspeaker (Kinyo ps-285b) placed about half a meter in front of the subject. CI subjects used their own CI and HA (if available) devices with daily programs. The volume control and sensitivity setting of the CI and HA remained unchanged during testing. All CI subjects except S1, S8, and S10 were tested with CI alone. S1 was not tested with CI alone due to time limitations, while S8 and S10 performed at chance level (50%) even for the most rising target tones during the practice with CI alone. All bimodal users were also tested with CI+HA. The CI alone and CI+HA conditions were tested in a counterbalanced order between bimodal users. Members of the CI alone and CI+HA test groups are indicated in Table 1. NH and CI subjects were tested with the same procedure as follows. Before each test, the task was explained and sample stimuli were tested for practice. There was no feedback during the tests.

Isolated tone recognition without context was first tested using a two-alternative, forced-choice (2AFC) task to make sure that the range of target onset F0 was sufficient for each subject to identify both Mandarin Tone 1 and Tone 2. The eight target stimuli were presented ten times in random order, resulting in a total of 80 trials. After listening to each stimulus, subjects chose the target tone by clicking on one of two response buttons shown on a computer screen. One button was labeled with “1” and a flat line denoting Tone 1, while the other was marked with “2” and a rising diagonal line denoting Tone 2. The percentage of Tone-2 responses was recorded for each target stimulus.

Only subjects with a typical S-shaped tone recognition function without context (all CI subjects except S8 and S10 in the CI alone condition and all bimodal users in the CI+HA condition) further participated in the tone recognition test with context. A similar procedure as in the test without context was adopted. The eight target stimuli preceded by either the high- or low-F0 context were presented ten times in random order, resulting in a total of 160 trials. The two contexts were randomly selected for different trials. The percentage of Tone-2 responses was recorded for each target stimulus with each context.

3. Results

3.1. Tone Recognition without Context

Figure 2 shows the percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition without context as a function of target onset F0 for NH subjects (panel a) and CI subjects tested with CI alone (panel b) or CI+HA (panel c). For each test group, a typical S-shaped tone recognition function was observed and a one-way repeated-measures (RM) analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant effect of target onset F0 on tone recognition without context (NH subjects: F7,63 = 120.90, p < 0.001; CI subjects with CI alone: F7,77 = 49.69, p < 0.001; CI subjects with CI+HA: F7,63 = 90.75, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition without context as a function of target onset F0 for NH subjects (panel a) and CI subjects with CI alone (panel b) or CI+HA (panel c). Symbols represent the mean, while error bars represent the standard deviation across subjects.

The tone recognition function without context for each subject (with either CI alone or CI+HA for bimodal users) was fitted with a sigmoid function as follows:

| (1) |

where y is the percentage of Tone-2 responses and x is the target onset F0. The parameter x0 is the perceptual boundary between Tone 1 and Tone 2 or equivalently the target onset F0 with 50% Tone-2 responses, and b is inversely proportional to the function slope and indicates a subject’s sensitivity to the target onset F0 changes. The estimated perceptual boundaries shown in Figure 3 were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA with hearing mode (NH, CI alone, or CI+HA) as the factor. There was a significant effect of hearing mode on the perceptual boundaries (F2,29 = 7.33, p = 0.003). Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction showed that CI subjects had similar perceptual boundaries with either CI alone or CI+HA (p > 0.99), although their perceptual boundaries were significantly lower than those of NH subjects (p = 0.01 for CI alone vs. NH and p = 0.005 for CI+HA vs. NH). On the other hand, the estimated function slopes were not significantly different across different hearing modes (one-way ANOVA: F2,29 = 2.17, p = 0.13).

Fig. 3.

Perceptual boundary for tone recognition without context for NH subjects (open bars) and CI subjects with CI alone (gray bars) or CI+HA (black bars). Symbols represent the mean, while error bars represent the standard deviation across subjects.

CI subjects’ perceptual boundaries or function slopes for tone recognition without context were not correlated with their recognition scores for naturally produced tones (see Table 3) in each test condition. In the CI+HA condition, no correlation was observed between tone recognition performance (i.e., the perceptual boundary or function slope for tone recognition without context or the recognition score for naturally produced tones) and measures of residual acoustic hearing (i.e., the aided threshold of the non-implanted ear at any frequency in Table 2 or the aided threshold averaged across frequencies). The age at testing, age at implantation, or duration of CI use (see Table 1) was also not correlated with the perceptual boundary or function slope for tone recognition without context or the recognition score for naturally produced tones in each test condition.

3.2. Tone Recognition with Context

Figure 4a shows the percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition with the low- and high-F0 contexts as a function of target onset F0 for NH subjects. A two-way RM ANOVA showed that tone recognition of NH subjects was significantly affected by both target onset F0 (F7,63 = 141.64, p < 0.001) and context F0 (F1,9 = 16.36, p = 0.003). There was a significant interaction between the two factors (F7,63 = 4.60, p < 0.001). The percentage of Tone-2 responses for NH subjects had ceiling or floor effects for target onset F0s from 160 to 220 Hz and from 280 to 300 Hz, respectively. For target onset F0s from 240 to 260 Hz, the high-F0 context led to small but significant increases (8%; p < 0.001) in Tone-2 responses as compared to the low-F0 context, consistent with previous studies with NH listeners (e.g., Huang and Holt, 2009).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition with the low-F0 (downward triangles) and high-F0 contexts (upward triangles) as a function of target onset F0 for NH subjects (panel a) and CI subjects with CI alone (panel b) or CI+HA (panel c). Symbols represent the mean, while error bars represent the standard deviation across subjects. For clarity of illustration, error bars are shown in only one direction.

Figure 4b shows the percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition with the low- and high-F0 contexts as a function of target onset F0 for CI subjects tested with CI alone. A two-way RM ANOVA showed that CI subjects’ tone recognition with CI alone was significantly affected by target onset F0 (F7,77 = 30.28, p < 0.001) but not by context F0 (F1,11 = 0.86, p = 0.37). However, the two factors significantly interacted with each other (F7,77 = 5.23, p < 0.001). Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction showed that the differences in Tone-2 responses between the two context F0s were only significant for the 200-Hz target onset F0 (p < 0.001). The two tone recognition functions with different context F0s were more separated for CI subjects than for NH subjects. However, with CI alone, the context effects on tone recognition were inconsistent across target onset F0s. The high-F0 context led to 7–24% more Tone-2 responses for target onset F0s from 160 to 240 Hz, while the low-F0 context led to 6–15% more Tone-2 responses for target onset F0s from 260 to 300 Hz. Among members of the CI alone test group, S9 and S11 had assimilatory (instead of contrastive) context effects and the percentage of their Tone-2 responses did not always decrease with increasing target onset F0s.

Figure 4c shows the percentage of Tone-2 responses for tone recognition with the low- and high-F0 contexts as a function of target onset F0 for CI subjects tested with CI+HA. A two-way RM ANOVA showed that CI subjects’ tone recognition with CI+HA was significantly affected by both target onset F0 (F7,63 = 57.55, p < 0.001) and context F0 (F1,9 = 18.50, p = 0.002). There was a significant interaction between the two factors (F7,63 = 6.11, p < 0.001). Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction showed that context effects were only significant for perceptually ambiguous target tones with onset F0s from 200 to 240 Hz (p < 0.001). All bimodal users exhibited contrastive context effects on tone recognition with CI+HA. The high-F0 context led to 7–33% more Tone-2 responses as compared to the low-F0 context for target onset F0s from 160 to 240 Hz.

Equation 1 was used to fit the tone recognition function with the low- or high-F0 context for each subject (with either CI alone or CI+HA for bimodal users). The fitting was successful for all NH and CI+HA cases. In the CI alone condition, the fitting was successful for most cases except for S7, S9, and S11 with the low-F0 context, where the percentage of Tone-2 responses did not always decrease with increasing target onset F0s. These unsuccessful cases were excluded from the following analyses. Figure 5 shows the estimated perceptual boundaries between Tone 1 and Tone 2 with the low- and high-F0 contexts in different hearing modes (NH, CI alone, or CI+HA). A two-way ANOVA showed that the perceptual boundaries significantly shifted with both context F0 (F1,52 = 9.86, p = 0.003) and hearing mode (F2,52 = 26.11, p < 0.001). Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction revealed that the high-F0 context led to significantly higher perceptual boundaries as compared to the low-F0 context (p = 0.003). CI subjects had similar perceptual boundaries with either CI alone or CI+HA (p > 0.99), although their perceptual boundaries were significantly lower than those of NH subjects (p < 0.001). The hearing mode and context F0 did not significantly interact with each other (F2,52 = 2.32, p = 0.11), although the boundary shifts with context F0 were greater with CI+HA (26 Hz) than with CI alone (10 Hz), and in turn than with NH (4 Hz).

Fig. 5.

Perceptual boundary for tone recognition with the low- and high-F0 contexts for NH subjects (open bars) and CI subjects with CI alone (gray bars) or CI+HA (black bars). Symbols represent the mean, while error bars represent the standard deviation across subjects.

Another two-way ANOVA revealed that the estimated function slopes were significantly different across hearing modes (F2,52 = 7.22, p = 0.002) but not across context F0s (F1,52 = 0.018, p = 0.89). There was no significant interaction between the two factors (F2,52 = 0.027, p = 0.97). Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni correction showed that CI subjects had similar function slopes with either CI alone or CI+HA (p > 0.99), although their tone recognition functions had significantly shallower slopes than those of NH subjects (p = 0.002 for CI alone vs. NH and p = 0.018 for CI+HA vs. NH).

For CI subjects, the size of the context effect on Tone 1-Tone 2 recognition in each test condition (as indicated by the difference between perceptual boundaries with the two context F0s) was not correlated with the recognition score for naturally produced tones (see Table 3), or with the age at testing, age at implantation, or duration of CI use (see Table 1). In the CI+HA condition, the size of the context effect on Tone 1-Tone 2 recognition was also not correlated with the aided threshold of the non-implanted ear at any frequency (see Table 2) or the aided threshold averaged across frequencies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Tone Recognition without Context

While Mandarin tone recognition of CI users has been extensively studied using naturally produced tones (e.g., Fu et al., 2004; Peng et al., 2004; Han et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013), this study presents the first report of CI users’ sensitivity to fine F0 changes in synthesized tones. Compared to NH subjects, CI subjects needed greater F0 increases to have 50% Tone-2 responses. The significantly lower perceptual boundaries of CI subjects reflected the fact that CIs provided only limited pitch cues (see Introduction). Also note that CI subjects (including preteens, teenagers, and young adults) were younger than NH subjects (young adults) in this study.Deroche et al. (2012) showed that school-aged children, even with normal hearing, may still have poorer pitch sensitivity than adults, possibly due to the limited ability to understand/process pitch cues and/or maintain a sustained level of attention during pitch tests. However, in this study, the age difference between CI and NH subjects may not have contributed to their different performance in tone recognition without context, because the perceptual boundary between Tone 1 and Tone 2 was not correlated with the age at testing for CI subjects. The comparison results would be more convincing if age-matched NH listeners were recruited from Taiwan and compared to CI subjects in this study.

With either CI alone or CI+HA, CI subjects’ ability to recognize the synthesized Tone 1-Tone 2 series did not reflect their ability to recognize naturally produced tones (see Table 3). The Tone 1-Tone 2 recognition test focused on pitch sensitivity because the synthesized stimuli differed only in onset F0. In contrast, naturally produced tones differ in factors in addition to pitch contour cues. For example, amplitude envelope and vowel duration cues have been shown to be useful for Mandarin tone recognition with CIs (e.g., Fu et al., 1998; Luo et al., 2004). The use of different cues may have reduced the performance correlation between the two recognition tests.

Previous CI studies (Peng et al., 2004; Han et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2013) have not found consistent results in relating the demographic factors to individual variability in tone recognition performance. Duration of CI use and age at implantation were identified as important predicting factors for tone recognition performance in a large-scale study of pediatric CI population (Zhou et al., 2013). This predictive relationship was however not observed in this study possibly because a smaller number of CI subjects were tested in this study and many of them were implanted at a much later age (after long-term hearing aid use) as compared to those inZhou et al. (2013).

Mandarin tone recognition with CI+HA was found uncorrelated with the aided thresholds of the non-implanted ear, which is similar to previous findings of English speech recognition with bimodal hearing (e.g., Ching et al., 2004; Gifford et al., 2007). Measures of pitch sensitivity and frequency resolution with the residual acoustic hearing may better predict tone recognition performance with CI+HA.

Contrary to our hypothesis, HA use in the non-implanted ear did not significantly improve CI subjects’ recognition of the synthesized Tone 1-Tone 2 series without context, in terms of both perceptual boundaries and function slopes. However, the fact that S8 and S10 were able to perform the task with CI+HA but not with CI alone suggests that HA use in the non-implanted ear was beneficial to their Tone 1-Tone 2 recognition. For the other bimodal users, the benefits of HA were overall limited for recognizing the Tone 1-Tone 2 series. However, the bimodal users as a group had significantly better recognition of naturally produced tones with CI+HA than with CI alone (see Table 3; paired t-test: t8 = 2.57, p = 0.03). Although not shown in Table 3, the improvement in natural tone recognition with bimodal hearing was greater for Tone 3 and Tone 4 than for Tone 1 and Tone 2, with an average increase of 13, 13, 7, and 2%, respectively. The residual acoustic hearing may have provided more acoustic cues to Tone 3 and Tone 4 (e.g., amplitude envelope cues in addition to pitch contour cues) than to Tone 1 and Tone 2.

4.2. Tone Recognition with Context

NH subjects exhibited small but significant contrastive context effects on tone recognition [i.e., had more (resp. fewer) Tone-2 responses in a high-F0 (resp. low-F0) context]. To facilitate the testing of CI subjects, this study adopted a larger range for target onset F0 than previous studies (e.g., Huang and Holt, 2009). As a result, the tested steps for target onset F0 were larger and NH subjects were provided with fewer perceptually ambiguous tones (between Tone 1 and Tone 2) that were subject to context effects. Nevertheless, the shifts in perceptual boundaries with context F0 for NH subjects in this study (~4 Hz) were similar to those in previous studies using smaller ranges and steps for target onset F0 (e.g., Huang and Holt, 2009).

With CI alone, CI subjects’ tone recognition greatly changed with context F0. The two tone recognition functions with the low- and high-F0 contexts however crossed each other, resulting in an insignificant overall context effect on tone recognition. Although the perceptual boundaries significantly shifted with context F0 in the CI alone condition, this analysis reflected only a single data point (with 50% Tone-2 responses) on the tone recognition function but not the complete pattern across target tones. The pitch contrast between context and target stimuli was primarily encoded by temporal periodicity cues in CIs and may not be salient enough to support consistent tone normalization for CI users.

When an HA was used in conjunction with the CI, contrastive context effects on tone recognition were consistently observed for bimodal users. The changes in Tone-2 responses and the shifts in perceptual boundaries with context F0 were greater for bimodal users than for NH subjects, although the group difference did not reach statistical significance. Compared to NH subjects, bimodal users were less sensitive to the target onset F0 changes, which could have made their tone recognition more susceptible to context effects. Although bimodal hearing did not improve the recognition of Tone 1-Tone 2 series without context, it induced more consistent context-dependent changes in Tone-2 responses. Residual acoustic hearing may partially resolve the F0 and/or the low18 numbered harmonics, which may have improved CI subjects’ ability to track the running F0 average of context, perceive the pitch contrast between context and target stimuli, and retune target tone recognition. It is also possible that bimodal hearing may ease a CI subject’s listening effort in tone recognition so that more cognitive resources such as attention and working memory may have been reserved for the use of the context pitch cues in tone normalization. As shown in Table 3, CI subjects’ response time for natural tone recognition was significantly shorter with CI+HA than with CI alone, indicating less listening effort or cognitive load with bimodal hearing. It remains unclear whether residual acoustic hearing alone is sufficient or whether it has to be combined with electric hearing to support consistent tone normalization with CI+HA. To answer this question, future studies should test the recognition of Tone 1-Tone 2 series with or without context in the HA alone condition.

The present results have theoretical implications for Mandarin tone normalization. Because cochlear processing was different in bimodal hearing and normal hearing, the contrastive context effects on tone recognition in the two hearing modes must have arisen from similar pitch-contrast processing at a central level beyond the cochlea (Huang and Holt, 2011). However, contrastive context effects on tone recognition were consistently observed with CI+HA but not with CI alone, suggesting that the central processing for tone normalization may be effective only with more salient pitch cues from the auditory periphery in the CI+HA condition. Demographic factors such as the age at testing, age at implantation, or duration of CI use did not affect CI subjects’ central processing for tone normalization. Note that the pre-lingually deafened CI subjects in this study acquired Mandarin via the use of CI and/or HA with degraded auditory inputs. It is encouraging to find that they also learned to use the context pitch cues for tone recognition from their limited tonal language experience.

The present results also have practical implications for CI users’ Mandarin tone normalization. With CI alone, not every CI user is able to use the context pitch cues to compensate for the pitch variability in Mandarin tones across speakers. However, tone normalization is possible and may greatly help multi-talker Mandarin tone and speech recognition when an HA was also used in the non-implanted ear. These results provided additional evidence of bimodal benefits by showing more consistent use of the context pitch cues for tone recognition with binaurally combined CI and HA than with CI alone. Similar benefits to tone normalization are also expected with the hybrid cochlear implants designed to preserve residual low-frequency acoustic hearing in the implanted ear using a short electrode array (e.g., Gantz et al., 2009).

Highlights.

-

-

Cochlear implant users listened to a Tone 1-Tone 2 series with or without context.

-

-

Tone recognition without context was similar with implant alone or bimodal hearing.

-

-

The context effect on tone recognition was not always contrastive with implant alone.

-

-

The contrastive context effect on tone recognition was significant for bimodal users.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the subjects who participated in this study and the support by the NIH Grant R21-DC-011844. Dr. Alexander Francis, Ching-Chih Wu, and Krista Ashmore provided constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Krista Ashmore also helped data collection at the Purdue University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: F0, fundamental frequency; NH, normal hearing; CI, cochlear implant; HA, hearing aid; RMS, root mean square; dB, decibel; RM, repeated measures; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

References

- Boersma P, Weenink D. [last accessed August 10, 2013];Praat: doing phonetics by computer. Version 5.3.17. 2012 http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/

- Chao YR. Mandarin primer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Wong LL, Hu Y. Effects of lexical tone contour on Mandarin sentence intelligibility. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013 doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0324). in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, Incerti P, Hill M. Binaural benefits for adults who use hearing aids and cochlear implants in opposite ears. Ear Hear. 2004;25:9–21. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000111261.84611.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche ML, Zion DJ, Schurman JR, Chatterjee M. Sensitivity of school-aged children to pitch-related cues. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012;131:2938–2947. doi: 10.1121/1.3692230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Gifford RH, Spahr AJ, Mckarns SA. The benefits of combining acoustic and electric stimulation for the recognition of speech, voice, and melodies. Audiol. Neurootol. 2008;13:105–112. doi: 10.1159/000111782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA, Best CT, McRoberts GW. Young infants’ perception of liquid co-articulatory influences on following stop consonants. Percept. Psychophys. 1990;48:559–570. doi: 10.3758/bf03211602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RA, Qi Y-Y. Context effects in the perception of lexical tone. J. Chin. Linguist. 1990;18:261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q-J, Hsu C-J, Horng MJ. Effects of speech processing strategy on Chinese tone recognition by Nucleus-24 cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2004;25:501–508. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000145125.50433.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q-J, Zeng F-G, Shannon RV, Soli SD. Importance of tonal envelope cues in Chinese speech recognition. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998;104:505–510. doi: 10.1121/1.423251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz BJ, Hansen MR, Turner CW, Oleson JJ, Reiss LA, Parkinson AJ. Hybrid 10 clinical trial: Preliminary results. Audiol. Neurootol. 2009;14:32–38. doi: 10.1159/000206493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts L, Wouters J. Coding of the fundamental frequency in continuous interleaved sampling processors for cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001;109:713–726. doi: 10.1121/1.1340650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RH, Dorman MF, McKarns SA, Spahr AJ. Combined electric and contralateral acoustic hearing: Word and sentence recognition with bimodal hearing. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2007;50:835–843. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/058). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green T, Faulkner A, Rosen S. Spectral and temporal cues to pitch in noise-excited vocoder simulations of continuous-interleaved-sampling cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002;112:2155–2164. doi: 10.1121/1.1506688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Liu B, Zhou N, Chen X, Kong Y, Liu H, Zheng Y, Xu L. Lexical tone perception with HiResolution and HiResolution 120 sound-processing strategies in pediatric Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2009;30:169–177. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31819342cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Holt L. General perceptual contributions to lexical tone normalization. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009;125:3983–3994. doi: 10.1121/1.3125342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Holt L. Evidence for the central origin of lexical tone normalization (L) J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011;129:1145–1148. doi: 10.1121/1.3543994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufnagle DG, Holt LL, Thiessen E. Spectral information in nonspeech contexts influences children’s categorization of ambiguous speech sounds. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2013;116:728–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y-Y, Stickney GS, Zeng F-G. Speech and melody recognition in binaurally combined acoustic and electric hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;117:1351–1361. doi: 10.1121/1.1857526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leather J. Speaker normalization in the perception of lexical tone. J. Phonetics. 1983;11:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu Q-J. Enhancing Chinese tone recognition by manipulating amplitude envelope: implications for cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;116:3659–3667. doi: 10.1121/1.1783352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu Q-J. Contribution of low-frequency acoustic information to Chinese speech recognition in cochlear implant simulations. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;120:2260–2266. doi: 10.1121/1.2336990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Fu Q-J, Wei C-G, Cao K-L. Speech recognition and temporal amplitude modulation processing by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 2008;29:957–970. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181888f61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CB, Jongman A. Speaker normalization in the perception of Mandarin Chinese tones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1997;102:1864–1877. doi: 10.1121/1.420092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S-C, Tomblin JB, Cheung H, Lin Y-S, Wang L-S. Perception and production of Mandarin tones in prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2004;25:251–264. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000130797.73809.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CW, Gantz BJ, Vidal C, Behrens A, Henry BA. Speech recognition in noise for cochlear implant listeners: Benefits of residual acoustic hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;115:1729–1735. doi: 10.1121/1.1687425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA. Pitch perception. Attention Percept. Psychophys. 2009;71:1701–1715. doi: 10.3758/APP.71.8.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng FG. Temporal pitch in electric hearing. Hear. Res. 2002;174:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Huang J, Chen X, Xu L. Relationship between tone perception and production in prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants. Otol. Neutotol. 2013;34:499–506. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318287ca86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]