Abstract

Objectives

Bipolar disorder (BP) has been associated with increased aggressive behaviors. However, all existing studies are cross-sectional and include forensic or inpatient populations and many do not take into account the effects of comorbid conditions. The goal of this study was to evaluate the longitudinal course of aggression among adult outpatients with BP compared with non-BP patients and healthy controls.

Methods

Subjects with bipolar I disorder (BP-I)/bipolar II disorder (BP-II) (n = 255), non-BP psychopathology (n = 85), and healthy controls (n = 84) (average 38.9 years, 78.7% female, and 84.9% Caucasian) were evaluated at intake and after two- and four-years of follow-up. Aggression was self-rated using the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ). Comparisons were adjusted for any significant demographic and clinical differences and for multiple comparisons. For subjects with BP, associations of AQ with subtype of BP, current versus past mood episodes, polarity and severity of the current episode, psychosis, and current pharmacological treatment were evaluated.

Results

In comparison with subjects with non-BP psychiatric disorders and healthy controls, subjects with BP showed persistently higher total and subscale AQ scores (raw and T-scores) during the four-year follow-up. There were no effects of BP subtype, severity or polarity of the current episode, psychosis, and current pharmacological treatments. Subjects in an acute mood episode showed significantly higher AQ scores than euthymic subjects.

Conclusions

BP, particularly during acute episodes, is associated with increased self-reported verbal and physical aggression, anger, and hostility. These results provide further evidence for the need of treatments to prevent mood recurrences and prompt treatment of acute mood episodes in subjects with BP.

Keywords: aggression, Aggression Questionnaire, anger, bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (BP) is a severe psychiatric disorder associated with serious psychosocial consequences and increased risk for suicidality, cardiovascular illnesses, substance abuse, and legal problems (1–3). The World Health Organization ranked BP among the top 10 most disabling disorders in the world (4).

BP has also been associated with increased risk for aggressive behaviors (5). However, all current studies are cross-sectional and the results have been confounded by the presence of other psychiatric conditions. Also, most of the studies have included forensic or inpatient populations limiting the generalizability of their findings. For example, Barlow and colleagues (6) found that inpatients with BP had significantly more aggressive behaviors than inpatients with other Axis-I disorders. In contrast, Biancosino and colleagues (7) reported that physical assault was equally prevalent in inpatients with BP, schizophrenia, substance/alcohol abuse, and ‘organic’ disorders. Fazel and colleagues (8, 9) reported significantly more violent behaviors in a large sample of adults with BP after discharge from the hospital compared with their siblings with non-BP psychopathology and the general population. However, these results were, in large part, accounted for by the presence of comorbid substance abuse. In a previous cross-sectional study, we compared aggression in adult outpatients with BP-I and BP-II with subjects with non-BP disorders and healthy controls, using the self-report Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) (10). After adjusting for confounding factors (e.g., demographic factors, treatment, and presence of non-BP psychopathology), subjects with BP reported significantly higher levels of anger and aggressive behaviors, especially during acute and psychotic episodes, compared to subjects with non-BP psychopathology and healthy controls (10). These results suggested that aggression, measured with the AQ, was specifically higher in adults with BP.

Since there are no longitudinal studies prospectively assessing aggressive behaviors of adults with BP, we sought to extend our prior findings (10) by evaluating whether the increased aggression found at intake in subjects with BP was stable over time. To do this, subjects with BP, non-BP subjects, and healthy controls were followed at least one time over a period of approximately four years. We hypothesized that after adjusting for confounding factors, subjects with BP would continue to report higher levels of aggression compared to the other two control groups.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited as part of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) (11). Details of the methods of this study are described elsewhere (11). Briefly, adults with BP (n = 255) were recruited through advertisement (53%), adult BP studies (31%), and outpatient clinics (16%). Subjects were required to fulfill DSM-IV criteria for BP-I or BP-II (12) and were excluded if they were diagnosed with schizophrenia, mental retardation, mood disorders secondary to substance abuse, medical conditions that impeded the participation in the study, or lived more than 200 miles away from Pittsburgh (PA, USA). Community control subjects (n = 169; 84 healthy and 85 with non-BP disorders) were recruited through the University of Pittsburgh Center for Social and Urban Research at a ratio of one control adult to two subjects with BP. Control subjects were group matched by age, sex, and neighborhood using the area code and the first three digits of the telephone number of the subjects with BP. The exclusion criteria were the same as for subjects with BP, with an additional exclusion criterion of BP and/or history of BP in first-degree relatives.

Only subjects with at least one follow-up assessment were included in this study (BP = 227, non-BP = 75, healthy controls = 81). No differences in clinical or demographic differences were found between subjects with and without follow-up assessments.

Assessment

After Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent were obtained, subjects were assessed at intake and every other year for psychopathology, family history of psychiatric disorders, and other variables such as psychosocial functioning, family environment and exposure to negative life events. Only instruments relevant to this article are included.

Axis-I disorders and severity of current mood episode were evaluated using the DSM-IV Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) (13) as well as the attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), disruptive behavior disorder (DBD), and separation anxiety disorder sections from the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (14). Overall functioning was evaluated using the DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (12). Current pharmacological treatments (mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, stimulants, and antidepressants) were ascertained using the Adult Health Medical Screening Interview developed for BIOS. Socioeconomic status (SES) was evaluated using the Four-factor Hollingshead Scale (15). The Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria method plus ADHD and DBD items from the K-SADS-PL were used to ascertain the psychiatric history of second-degree relatives and biological co-parents not seen for direct interview. All assessments were completed by bachelors- or masters-level interviewers with at least two years of experience and were carried out in the subjects’ homes. All assessments were presented to a psychiatrist who was blind to the psychiatric status of the subjects. Inter-rater reliability for the SCID and KSADS was acceptable (kappa ≥ 0.8).

Lifetime aggression was evaluated through the AQ (16). During the follow-up, subjects were instructed to report only those changes noted since the last evaluation. The AQ is an updated version of the classic Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (17), a widely known instrument for assessing lifetime anger and aggression. The internal consistency estimate of the AQ is 0.94 and the AQ has strong construct and discriminant validity (17). The AQ includes 34 items scored on five subscales: Physical Aggression (PHY), Verbal Aggression (VER), Anger (ANG), Hostility (HOS), and Indirect Aggression (IND). The PHY subscale includes items focused on the use of physical force when expressing anger: ‘I may hit someone if he or she provokes me.’ The VER subscale is formed by items that make reference to hostile speech: ‘When people annoy me, I may tell them what I think of them.’ The items of the ANG subscale describe aspects of anger related to arousal and sense of control: ‘At times I feel like a bomb ready to explode.’ The HOS subscale refers to attitudes of social alienation and paranoia: ‘I wonder what people want when they are nice to me.’ Finally, the IND subscale measures the tendency to express anger in actions that avoid direct confrontation: ‘When someone really irritates me, I might give him/her the silent treatment.’

Each of the items describes a characteristic related to aggression, and the individual rates the description on a Likert scale from 1 (Not at all like me) to 5 (Completely like me) to form an AQ Total score along with an Inconsistent Responding (INC) index score as a validity indicator. The INC is based on several pairs of items for which responses tend to be similar among individuals, for example: ‘If somebody hits me, I hit back,’ and ‘If I have to resort to violence to protect my rights, I will.’ If the difference score between these pairs is bigger than one point, then the INC score increases one point. The developers of the AQ suggest questioning the accuracy of the individual's response when the INC is ≥ 5.

Total and subscale AQ scores can be reported as raw or T-scores. The T-norms were standardized in a sample of more than 2,000 individuals, aged 9–88 years, considered as representative of the US population (18).

Statistics

Between-group demographic and clinical comparisons were done using standard parametric and non-parametric statistics as appropriate. Longitudinal total and subscale AQ scores among BP, non-BP, and healthy control groups were compared using mixed models, both with and without adjustment for significant covariates.

Within the BP group, the BP type (BP-I/BP-II), the presence of a current mood episode (defined as within the month preceding the assessment), polarity of current episode (manic/mixed, hypomanic, depressed, and not otherwise specified), the severity of current episode (mild, moderate and severe), and current exposure to pharmacological treatments were evaluated using mixed models.

Log transformation was performed to total and subscale raw AQ scores to achieve normal distributions. T-scores were also evaluated; with very few exceptions, both analyses yielded similar results. Therefore, for simplicity, only results using raw AQ scores are presented. All pair-wise comparisons were conducted with Bonferroni corrections. All p-values were based on two-tailed tests with α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 or SPSS 19.

Results

As shown in Table 1, 227 subjects with BP, 75 subjects with non-BP psychopathology, and 81 healthy controls were included in the analyses. Subjects were followed an average of 3.9 years (median = 4.04 years, standard deviation = 1.04) and were assessed approximately at two years (Time 2) (BP = 220, non-BP = 74, healthy controls = 80) and at four years (Time 3) (BP = 186, non-BP = 66, healthy controls = 79).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at Time 1

| Bipolar disorder (n = 227) | Non-BP (n = 75) | Healthy controls (n = 81) | Statistics | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 38.99 (7.8) | 39.51 (9.0) | 39.21 (7.5) | F = 0.12 | 0.9 |

| Sex, % female, mean (SD) | 179 (78.9) | 59 (78.7) | 61 (75.3) | F = 0.46 | 0.8 |

| Race, % white, mean (SD) | 204 (89.9) | 60 (80.0) | 66 (81.5) | F = 6.50 | 0.04 |

| Marital status, % living together, mean (SD) | 120 (52.9)a | 44 (58.7)a | 66 (81.5)b | F = 20.46 | < 0.0001 |

| SES, mean (SD) | 35.10 (14.7)a | 36.35 (13.1)a,b | 40.86 (13.6)b | F = 4.95 | 0.008 |

| Lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorders, n (%) | |||||

| Bipolar I disorder | 154 (67.8) | - | - | ||

| Bipolar II disorder | 73 (32.2) | - | - | ||

| MDD | 33 (44.0) | - | |||

| Dysthymic disorder | 9 (12.0) | - | |||

| Psychosis | 24 (10.6) | 2 (2.7) | X2 = 4.5 | 0.03 | |

| ADHD | 57 (25.1) | 6 (8.0) | X2 = 10.0 | 0.002 | |

| Disruptive behavior disorder | 79 (34.8) | 9 (12.0) | X2 = 14.2 | 0.0002 | |

| ODD | 61 (26.9) | 5 (6.7) | X2 = 13.5 | 0.0002 | |

| Conduct disorder | 46 (20.3) | 5 (6.7) | X2 = 7.4 | 0.006 | |

| Substance use disorder | 143 (63.0) | 38 (50.7) | X2 = 3.6 | 0.06 | |

| Alcohol | 117 (51.5) | 30 (40.0) | X2 = 3.0 | 0.08 | |

| Drugs | 96 (42.3) | 22 (29.3) | X2 = 4.0 | 0.05 | |

| Any anxiety | 167 (73.6) | 26 (34.7) | X2 = 37.0 | < 0.0001 | |

| Panic disorder | 90 (39.7) | 6 (8.0) | X2 = 26.0 | < 0.0001 | |

| SAD | 22 (9.7) | 7 (9.3) | X2 = 0.008 | 0.9 | |

| GAD | 63 (27.8) | 4 (5.3) | X2 = 16.4 | < 0.0001 | |

| PTSD | 83 (36.6) | 12 (16.0) | X2 = 11.1 | 0.0009 | |

| OCD | 31 (13.7) | 2 (2.7) | X2 = 7.0 | 0.008 | |

| Social phobia | 56 (24.7) | 5 (6.7) | X2 = 113 | 0.0008 | |

| Eating disorders | 21 (9.3) | 2 (2.7) | X2 = 3.5 | 0.06 | |

Different superscripts indicate significant differences among groups with p-values < 0.05 after Bonferroni's correction. ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; SD = standard deviation; SES = socioeconomic status.

At intake (Time 1), subjects with BP and non-BP psychopathology were less likely to be married than the healthy controls. Also, subjects with BP and non-BP had lower SES than the healthy controls (for all above noted comparisons, p-values < 0.05). Subjects with BP had significantly higher lifetime prevalence of ADHD, DBD, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia, and eating disorder when compared to the non-BP group (all p-values < 0.05). There were no differences in demographics and clinical characteristics between subjects with or without follow-up assessments.

At Time 2, nine subjects (BP = 7, non-BP = 1, healthy controls = 1) and at Time 3, 12 subjects (BP = 9, non BP = 2, healthy controls = 1) dropped from the study. In addition, 31 subjects had not been followed-up (BP = 25, non-BP = 6). There were no differences in demographics and clinical characteristics between subjects included in this analysis and those who dropped out or had not been interviewed.

AQ raw scores

As depicted in Table 2, after adjusting for between-group significant demographic and clinical differences, there were significant time, group, and time × group interactions for the three groups in total scores and every AQ subscale (all p-values < 0.05) with the exception of the time × group interaction for the physical and the indirect subscales.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) raw total and each subscale score among subjects with bipolar disorder (BP), non-BP psychopathology, and healthy controls (HC)

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Statisticsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Time | Time × Group | |||||||

| F | p-value | F | p-value | F | p-value | ||||

| AQ total | 67.75 | < 0.0001 | 25.10 | 0.0001 | 4.88 | 0.009 | |||

| BP | 87.06 ± 27.56 | 78.61 ± 26.69 | 77.52 ± 28.69 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 64.12 ± 20.39 | 63.28 ± 23.54 | 59.76 ± 16.81 | ||||||

| HC | 53.80 ± 12.55 | 50.66 ± 11.20 | 49.59 ± 10.10 | ||||||

| Physical total | 31.50 | < 0.0001 | 18.12 | < 0.0001 | 2.89 | 0.06 | |||

| BP | 16.74 ± 8.12 | 14.90 ± 7.17 | 15.05 ± 8.09 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 13.01 ± 5.30 | 12.57 ± 5.58 | 11.83 ± 3.69 | ||||||

| HC | 10.43 ± 3.15 | 10.16 ± 3.03 | 10.17 ± 3.13 | ||||||

| Verbal total | 33.18 | 0.0001 | 4.83 | 0.03 | 4.98 | 0.007 | |||

| BP | 13.76 ± 5.20 | 12.46 ±4.96 | 12.33 ± 5.23 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 10.63 ± 3.34 | 10.39 ±4.19 | 10.03 ± 3.39 | ||||||

| HC | 8.96 ± 2.57 | 8.76 ± 2.44 | 8.99 ± 2.62 | ||||||

| Anger total | 60.24 | < 0.0001 | 15.65 | 0.0001 | 5.62 | 0.005 | |||

| BP | 19.99 ± 6.98 | 17.72 ± 6.97 | 17.65 ± 6.80 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 13.75 ± 5.19 | 14.12 ± 5.75 | 13.53 ± 5.60 | ||||||

| HC | 11.78 ± 3.43 | 10.58 ± 2.89 | 10.49 ± 2.74 | ||||||

| Hostility total | 62.38 | < 0.0001 | 15.29 | 0.0002 | 3.63 | 0.03 | |||

| BP | 22.18 ± 8.32 | 20.17 ± 8.26 | 19.42 ± 8.36 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 14.69 ± 5.96 | 14.86 ± 7.10 | 13.62 ± 5.25 | ||||||

| HC | 12.57 ± 4.53 | 11.83 ± 4.67 | 11.01 ± 3.74 | ||||||

| Indirect total | 27.13 | < 0.0001 | 24.98 | < 0.0001 | 0.38 | 0.70 | |||

| BP | 14.44 ± 4.70 | 13.36 ± 4.68 | 13.10 ± 4.97 | ||||||

| Non-BP | 12.03 ± 4.33 | 11.32 ± 4.19 | 10.78 ± 3.31 | ||||||

| HC | 10.04 ± 2.90 | 9.36 ± 2.52 | 8.93 ± 2.05 | ||||||

For all group comparisons: BP > non-BP; BP > healthy controls and non-BP > healthy controls with p-values ≤ 0.05 after Bonferroni's correction.

Adjusted for race, marital status, and socioeconomic status.

Pair-wise comparisons adjusting for between-group clinical and demographic differences and multiple comparisons showed that subjects with BP had significantly higher overall total and individual subscale AQ scores than subjects with non-BP psychopathology (all p-values < 0.05). Also, BP subjects showed significantly higher total AQ scores and in each one of the subscales than the healthy controls. There were no differences in the overall total AQ and each of the subscales between the non-BP and healthy controls.

After adjusting for between-group demographic and clinical differences and multiple comparisons, pair-wise comparisons of the time by group interactions showed a significant decrease in the AQ total and anger in the subjects with BP when compared to non-BP subjects. Subjects with BP also had lower PHY and VER scores when compared to healthy controls (all p-values < 0.05, results available upon request). Also, non-BP subjects showed a significant decrease in anger when compared to the healthy controls (p < 0.05).

After excluding from the above-noted analyses subjects with an AQ ‘inconsistency index’ ≥ 5 (BP = 127, non-BP = 24, healthy controls = 13), similar results were obtained. It is also important to highlight that subjects who participated in this study had worse punctuation in the AQ scores than those subjects who did not, although results were not statistically significant (results available upon request).

Within the BP group, subjects experiencing a mood episode at intake and during the follow-up (Time 1 = 149, Time 2 = 105, Time 3 = 77) showed significantly higher scores on the total and all the subscales of the AQ, in comparison with subjects who were not in a current mood episode (all p-values < 0.05). Adjusting for between-group demographic, clinical differences, and current use of psychotropic medications (any medication, antipsychotics, antidepressants, stimulants, and mood stabilizers) yielded similar results. In addition, there were no effects of BP subtype (BP-I or BP-II), polarity of the episodes (e.g., hypomanic, manic/mixed, depressed, not otherwise specified), severity (mild, moderate, severe), presence of psychosis (delusions and/or hallucinations), and familial history of BP.

To evaluate whether the high AQ scores in the subjects with BP were accounted by the recruitment of patients attending clinical settings, and as a consequence having more severe disorders that those recruited by other means, an analyses comparing the intake AQ scores between those subjects with BP who were recruited thorough advertisement versus clinics was done. Subjects recruited through advertisement showed higher scores on the physical, anger, and total AQ scores (all p-values < 0.02). There were no differences on the verbal, hostility, and indirect subscales.

Overall functioning

After adjusting for between-group demographic and clinical differences at intake and during the follow-up, there were significant group (F = 53.4, p < 0.001), and time × group (F = 9.1, p < 0.001) differences in the overall functioning of all the subjects. Pair-wise comparisons adjusting for multiple comparisons and confounding variables showed that subjects with BP had lower functioning when compared to subjects with non-BP (p-values < 0.001) and the healthy controls (p-value < 0.001). Finally, subjects with non-BP showed lower functioning when compared to healthy controls (p-value < 0.05). For the overall sample, there was a significant negative correlation between AQ total score and overall functioning (Pearson's correlation coefficient = −0.55, p ≤ 0.001).

Discussion

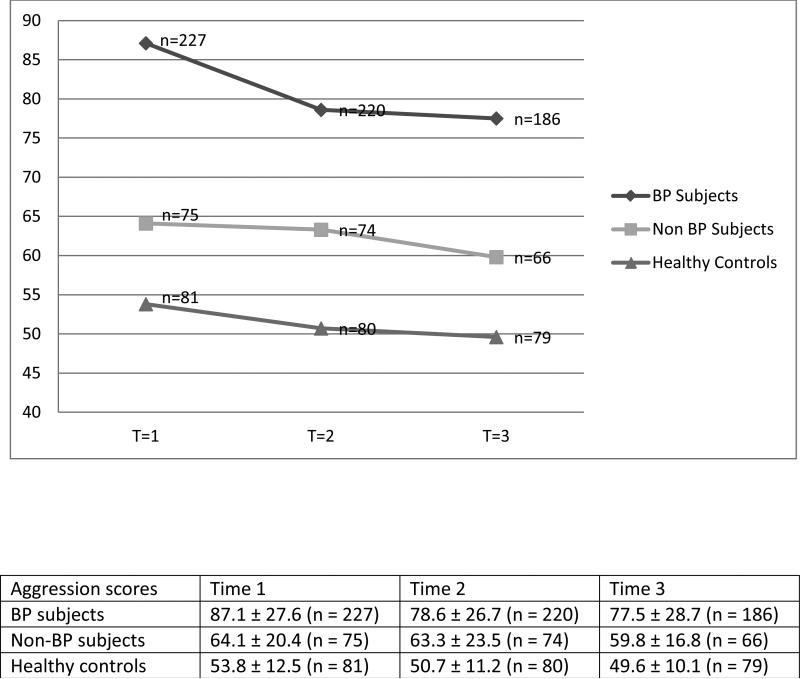

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study of adult BP in the literature that has evaluated aggression in subjects with BP in comparison to subjects with non-BP psychopathology and healthy controls. After adjusting for between-group demographic and clinical differences, during the four-year follow-up, subjects with BP showed persistently higher scores in the total and on each of the AQ subscales than the other two groups (Fig. 1). As expected, subjects with non-BP psychopathology also showed higher AQ scores than the healthy controls. In contrast to the subjects with BP, subjects with non-BP psychopathology did not show any difference in AQ total or any subscale when compared to healthy controls after adjusting for confounding clinical factors. Within the BP group, the total and subscale AQ scores were significantly higher during an acute mood episode. The severity, polarity or the presence of psychosis, or current pharmacological treatments did not affect the AQ scores. The higher AQ scores in the subjects with BP was not due to the recruitment from clinical settings, since subjects recruited through advertisement showed higher AQ scores. Finally, for all groups there was a significant correlation between the aggression scores and overall functioning. After adjusting for confounding factors, subjects with BP had significantly lower functioning when compared to subjects with non-BP psychopathology and healthy controls. Also, subjects with non-BP showed lower overall functioning than healthy controls.

Fig. 1.

Aggression raw scores between subjects with bipolar disorder (BP), non-BP psychopathology, and healthy controls. T = time. Group F = 67.75, p < 0.001; Time F = 25.1, p < 0.001; Interaction Time × Group F = 4.88, p < 0.05.

Before discussing the above-noted results in more detail, the limitations of this study need to be highlighted. First, the results may not be generalizable to other populations because the sample was recruited through a high-risk study (BIOS) (11). However, the lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the sample was similar to that reported in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (19). Also, the rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders in subjects with BP in our sample were similar to those reported in the adult BP literature (19, 20). Second, although we excluded subjects with mental retardation, cognitive function was not formally evaluated. In addition, we did not evaluate the effects of personality disorders. Third, the prevalence of psychosis in our sample was low (2%). Fourth, the information collected in this study was obtained only from subjects’ self-evaluations and not from their relatives or criminal reports. Consequently, subjects could have under- or over-reported their aggressive behaviors. However, this potential bias might affect not only subjects with psychiatric disorders, but also healthy controls. In fact, in a large community study of adults with psychiatric disorders and healthy controls, the tendency to over-report aggression was not only present in adults with psychopathology, but also in the controls (21). Finally, only the effects of psychopharmacological, and not the psychosocial treatments during the current episode were analyzed. However, given that this study is naturalistic, these results need to be taken with caution.

The results of this study corroborate our prior cross-sectional findings (10) and suggest that BP is associated with high levels of self-reported aggression over time, especially during an acute mood episode. The fact that the aggression scores continued to be significantly higher after taking into account the presence of non-BP illnesses, suggest that BP specifically is associated with aggression. Existing studies have also reported increased aggression and anger associated with BP in comparison with patients with non-BP psychopathology [(22); see review by Lavatolav (5)]. For example, Perlis et al. (23) found that the presence of anger attacks during pure depressive episodes was twice as common among BP (62%) when compared to unipolar depressed patients (26%). However, most of these studies have only focused on the presence of aggression in patients with BP who were in an acute episode and all of them were cross sectional.

Comparable with our prior study (10) and Fazel and colleagues (8), there were no effects of the subtype of BP or the polarity of the current episode on the aggression scores. In contrast, perhaps due to methodological differences (e.g., definition of aggression and inpatient status), Graz and colleagues (24) reported significantly higher rate of criminal behaviors in patients while in mania when compared with patients with bipolar or unipolar depression. Finally, in agreement with our last study (10), we also found that there were no effects of the severity of the current episode of BP in aggression. The reason of these counterintuitive findings is not entirely clear, but it is possible that aggression as measured through the AQ is specifically related to BP independently of the severity of the episode.

In general, psychosis has been found to be associated with increased risk for aggression. In contrast with the general literature (25) and our prior report (10), perhaps due to a lack of statistical power, in this analysis the presence of psychosis in subjects with BP was not specifically associated with aggression.

The finding that subjects with BP reported more aggressiveness may be a potential source of stigma and discrimination against people suffering from BP (26). However, it is important to emphasize that the above results do not mean that subjects with BP are more prone to severe violent behaviors such as homicide, rape, or the use of weapons. In fact, the AQ does not measure severe violent behaviors; it measures hostility, verbal and physical aggression, irritability, and indirect aggression. Moreover, a recent large study by Fazel et al. (8, 9) showed that patients with BP had more violent behaviors (e.g., homicide, assault, robbery, sexual offenses), but the results were in large part accounted for by the use of substances and not BP per se.

In conclusion, independent of the BP subtype, polarity, comorbidity, severity of mood episodes, and the use of medications, subjects with BP, particularly when acutely ill, reported more verbal and physical aggression, anger, and hostility than subjects with non-BP psychopathology and healthy controls, and these differences are stable over time. The results of this study provide further evidence for the importance of prevent mood recurrences and implement psychosocial and pharmacological treatments to help subjects with BP manage their aggressiveness. Successful acute treatment and prevention of recurrences will improve the well being, minimize interpersonal and family conflicts, and hopefully prevent the development of more severe violent behaviors in subjects with BP.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) grant #MH060952 to BB. The content of this paper does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH. The authors thank Melissa Cade, Mary Kay Gill, and Edward Wirkowski for assistance with manuscript preparation and all of the staff members at the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) for their support. We especially want to thank all of the participants with bipolar disorder and their families who have cooperated selflessly and patiently in all of the evaluation processes.

Footnotes

Disclosures

BB has received research support from NIMH; has served as a consultant for Schering Plough; and receives royalties from UpToDate, Random House, Inc., and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. JB, BG, TRG, HY, DA, KM, MBH, RSD, DJS, GS, SI, DJK, and DAB report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ösby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparén P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psych. 2001;58:844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psych. 2002;159:1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. ninth edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive Illness: Bipolar Disorders and Recurrent Depression. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavatolav K. Bipolar disorder and aggression. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:889–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barlow K, Grenyer B, Ilkiw-Lavalle O. Prevalence and precipitants of aggression in psychiatric inpatient units. Aust N Z J Psych. 2000;34:967–974. doi: 10.1080/000486700271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biancosino B, Delmonte S, Grassi L, et al. Violent behavior in acute psychiatric inpatient facilities: a national survey in Italy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:772–782. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181bb0d6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Grann M, Goodwin GM, Långström N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime: new evidence from population-based longitudinal studies and systematic review. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67:931–938. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazel S, Lichtenstein P, Frisell T, Grann M, Goodwin G, Långström N. Bipolar disorder and violent crime: time at risk reanalysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1325–1326. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.171. Erratum in: Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballester J, Goldstein T, Goldstein B, et al. Is bipolar disorder specifically associated with aggression? Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psych. 2009;66:287–296. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders Research Version (SCID-I, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psych. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University Sociology Department; New Haven: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21:343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buss AH, Warren WL. Aggression Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psych. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psych. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva PA. Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: results from the Dunedin Study. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:979–986. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colasanti A, Natoli A, Moliterno D, Rossattini M, De Gaspari IF, Mauri MC. Psychiatric diagnosis and aggression before acute hospitalisation. Eur Psych. 2008;23:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perlis RH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Nierenberg AA, Sachs GS. The prevalence and clinical correlates of anger attacks during depressive episodes in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004;79:291–295. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graz C, Etschel E, Schoech H, Soyka M. Criminal behaviour and violent crimes in former inpatients with affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al. A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psych. 2006;63:490–499. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey on the frequency of violent behavior in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psych Res. 2005;136:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]