Abstract

Transcription regulation of the Drosophila hsp70 gene is a complex process that involves regulation of multiple steps including establishment of paused Pol II and release of Pol II into elongation upon heat shock activation. While the major players involved in regulation of gene expression have been studied in detail, additional factors involved in this process continue to be discovered. To identify factors involved in hsp70 expression, we developed a screen that capitalizes on a visual assessment of heat shock activation using a hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter and publicly available RNAi fly lines to deplete candidate proteins. We validated the screen by showing that depletion of HSF, CycT, Cdk9, Nurf 301, or ELL prevented full induction of hsp70 by heat shock. Our screen also identified the histone deacetylase HDAC3 and its associated protein SMRTER as positive regulators of hsp70 activation. Additionally we show that HDAC3 and SMRTER contribute to hsp70 gene expression at a step subsequent to HSF-mediated activation and release of the paused Pol II that resides at the promoter prior to heat shock induction.

Keywords: hsp70, HDAC3, SMRTER, RNA polymerase II, transcription, heat shock

1. INTRODUCTION

Transcriptional control of protein-encoding genes in eukaryotes involves the complex interplay of sequence specific DNA binding proteins, nucleosome organization and composition, chromatin modifying and remodeling activities and the general transcriptional machinery. The hsp70 heat shock gene of Drosophila has served as a model for deciphering the roles of these various components of the transcription process. Regulation of hsp70 can be divided into distinct steps that include establishment of a paused Pol II, activation and release of the paused Pol II, productive elongation and termination of transcription. Various factors are implicated in regulating these distinct steps. The uninduced hsp70 gene is one of the earliest genes shown to have a transcriptionally engaged Pol II, paused at the +20 to +40 region (1). It is now known that pausing occurs on numerous genes in Drosophila (2–4). Under normal conditions, hsp70 is transcribed at low levels but within seconds undergoes a several hundred-fold increase in transcription in response to heat shock (5). This rapid activation is brought about by the activities of a number of factors including the heat shock factor, HSF and the Pol II kinase, P-TEFb (6, 7). The rapid induction of the heat shock genes and the ability to visualize the binding and behavior of transcription factors at the heat shock loci in vivo makes it an ideal model gene to study transcription mechanisms (8).

We developed a screen for proteins that affect hsp70 transcription by taking advantage of the collection of Gal 4 inducible RNAi fly lines available to the Drosophila community (9). The GAL4/UAS system was used to induce expression of RNAi in Drosophila salivary glands to direct the depletion of specific proteins, and an hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter gene was used to monitor the impact of the depletion on heat shock activation of the hsp70 promoter. Our screen revealed that depletion of the histone deacetylase HDAC3 and its co-repressor protein SMRTER inhibited heat shock activation of the hsp70 promoter. This was unexpected because HDACs are generally thought to function as repressors (10).

Although histone deacetylase activity is correlated with repression of transcription, genome wide maps indicate that HDACs are widely associated with active genes (11). It has been proposed that HDACs function on active genes to reset the chromatin to a state required for reinitiation by removing acetyl groups laid down by the histone acetyltransferases associated with the transcribing RNA Pol II(11, 12). This model still implies the HDAC is serving a repressive, yet transient, role by removing marks of active chromatin. HDAC binding was also observed on genes that are not expressed but are associated with the active chromatin mark H3K4me3 and hence are considered “primed” for transcription, suggesting that HDACs function to maintain these genes repressed prior to activation (11).

Histone deacetylases are classified into three major groups. Class I is comprised of proteins that share sequence similarity with the yeast repressor protein, Rpd3, whereas Class II is defined by sequence similarity with the yeast deacetylase, Hda1(13). Classes I and II are zinc dependent enzymes. In metazoans, class I enzymes are expressed in almost all cell types, while expression of Class II histone deacetylases are restricted to specific tissues, suggesting their involvement in developmental processes (14). Class III contains the NAD+ dependent histone deacetylases. In humans, there are 11 histone deacetylases that are categorized in these 3 classes. Class I includes HDAC1, 2,3 and 8. Class II contains HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10. Class III contains the sirtuin proteins Sirt1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (14).

Drosophila contains only 5 HDACs that are divided into the three classes mentioned above. Class I is comprised of HDAC1 and HDAC3. Class II histone contains the proteins HDAC4 and HDAC6, of which dHDAC6 can exist in two different splice variants, HDAC6L and HDAC6S. Sir2 comprises the third class of histone deacetylases (15–17). Of these proteins, HDAC1 and Sir2 are mostly nuclear and HDAC6 is mostly cytosolic. The other HDACs are found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (15, 17).

In Drosophila tissue culture cells, RNAi-mediated depletion of the various HDACs revealed that only depletion of HDAC1 and HDAC3 affected transcription (18). Microarray analysis showed that depletion of HDAC1 resulted in up-regulation of 494 genes and down-regulation of 338 genes. Depletion of HDAC3 caused 29 genes to be up–regulated and 35 genes to be down-regulated (18).

HDAC3 has been shown to be important for development and growth as RNAi mediated depletion of HDAC3 from Drosophila causes lethality at the third instar larval stage and mutations in HDAC3 are homozygous lethal at late larval stages (19, 20). HDAC3 is also involved in the PI3K signaling pathway that is involved in controlling organ growth (19). Hdac3 mutant flies showed decreases in the size of imaginal discs, which results from increased expression of the pro-apoptotic gene hid (20). HDAC3 knockout mice die at the embryonic stage (21).

Experiments in the Drosophila embryo showed that HDAC3 activity is involved in early development, and histone deacetylation by HDAC3 is important in repression mediated by the co-repressor Ebi. Ebi interacts with the HDAC3-SMRTER complex and regulates the activity of Snail, a repressor that is important in embryonic development (22). Recently HDAC3 was shown to be involved in maintaining the nucleosome organization on the Drosophila hsp70 gene prior to heat shock induction (23). HDAC3 appears to inhibit the activity of the enzyme PARP (Poly ADP –Ribose Polymerase), which is involved in nucleosome depletion from hsp70 during heat shock.

Our screen identified HDAC3 and its associated factor SMRTER as positive regulators of expression of hsp70. Further analysis revealed that loss of HDAC3 decreased the level of Pol II associated with hsp70 during heat shock, thus implicating HDAC3 as a positive regulator of transcription at this gene. Further analysis also revealed that HDAC3 contributes to hsp70 expression at some point subsequent to activating the paused Pol II that resides at the hsp70 promoter prior to heat shock.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Fly lines and nomenclature

The following fly lines containing RNAi transgenes were used in this study. Most of the RNAi fly lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Research Center and their accession numbers are HSFi (VDRC 37699), Cdk9i (VDRC 30449), CycTi (VDRC 37562), Nurf301i (VDRC 46645), HDAC3i#1 (VDRC-KK 107073), HDAC3i#2 (VDRC 20184) and SMRTERi (VDRC-KK 106701), Rpd3i#1 (VDRC 30600). Rpd3i#2 (BDSC 33725) was obtained from the Bloomington stock center. The ELL RNAi fly line was obtained from Ali Shilatifard. The yw; Z243,1824 fly line was constructed by recombining a hsp70-beta gal transgene (Z243 provided by John T. Lis) and a transgene that expresses Gal4 in salivary glands (1824, BDSC 1824 from the Bloomington stock center) onto the same chromosome. The control fly line with no RNAi transgenes was yw.

2.2 Primers used in assays

| Primer no. | Primer(s) | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RealT Rp49F | 5′-GCGTCGCCGCTTCAAG |

| 2 | RealT Rp49R | 5′-CAGCTCGCGCACGTTGT |

| 3 | Hsp70 +1916F | 5′-ACTGGACGAGGCCGACAAG |

| 4 | Hsp70 +2036R | 5′-GCGAGTGAGCTCCTCCATCT |

| 5 | Hsp70 +16/+115 F | 5′-GCAAAGTGAACACGTCGCTAAG |

| 6 | Hsp70 +16/+115 R | 5′-ATTGATTCACTTTAACTTGCACTTTACTG |

| 7 | Hsp70 +825/897 F | 5′-GGTGAGCGCAATGTGCTTATC |

| 8 | Hsp70 +825/897 R | 5′-AGCGCACCTCGAACAGAGAT |

| 9 | Hsp70 +250 LM1 | 5′-GCAGGCATTGTGTGTGAGT |

| 10 | Hsp70 +250 LM2 | 5′-GGCATTGTGTGTGAGTTCTTCTTT |

| 11 | Hsp70 +250 LM3 | 5′TGTGTGAGTTCTTCTTTCTCGGTAACTTG |

2.3 Beta-galactosidase staining assay

The beta-galactosidse staining assay was adapted from Zink and Paro (24). Third instar larvae from control and RNAi fly lines that were mated with yw; Z243,1824 flies were heat shocked at 37°C for 30 minutes The larvae were recovered at room temperature. Salivary glands were dissected in dissection buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2). The glands were then incubated in 1% gluteraldehyde solution (diluted in dissection buffer) for 5 minutes. Next, they were transferred to 100 μl of X-gal staining solution that was prepared by diluting 100 μl of X-gal (20 mg/ml) to 1 ml of stain solution (10 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.7 mM K4[FeII (CN)6], 6 mMK3[FeIII (CN)6], 0.3% Triton x-100) pre-warmed at 37°C for 5 minutes. The glands were gently rotated for 2 hour and then washed with dissection buffer, placed in a drop of 100% glycerol and photographed under a stereo microscope.

2.4 Reverse transcription PCR analysis

10 pairs of dissected salivary glands in 10 μl of S2 culture medium (Invitrogen) were either processed directly for non heat shocked samples or heat shocked at 37°C for 10 minutes in a heated PCR block. Total RNA was isolated from 10 pairs of salivary glands using 200 μl of Trizol following manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). 200 ng of RNA was incubated with 0.5 μM oligo dT and 150 ng random hexamers (Invitrogen) at 65°C for 5 minutes. Reverse transcription was carried out at 37°C for one hour with 100 units of MMLV-RT enzyme (Promega) in the presence of 1x transcription buffer (diluted from 5x buffer provided by manufacturer), 10 μM DTT and 0.2 units of RNasin (Promega). The reaction was stopped by incubation at 75°C for 5 minutes. cDNA was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR analysis with gene specific primers.

2.5 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation of salivary glands

ChIP was done as previously described (25). 10 pairs of salivary glands were isolated in dissection buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2) and then transferred to 10 μl S2 media in a thin-walled PCR tube. The glands were heat shocked at 37°C for 10 minutes in a heated PCR block. Following heat shock, 90 μl of ice-cold dissection buffer was added followed by addition of 37% formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%. Glands were incubated on ice for 5 minutes and then at room temperature for 7 minutes. The crosslinking reaction was quenched by addition of glycine (2.5 M) to a final concentration of 125 mM and the reaction was incubated on ice for 2 minutes. The glands were pelleted by centrifugation at 900 x g for 2 minutes at 4°C and supernatant was discarded. The glands were homogenized in 100 μl sonication buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.5 % SDS, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail). The homogenized material was sonicated at 4°C in a Diagenode Bioruptor at full frequency for 15 minutes at 30 seconds on/30 seconds off cycle to shear the chromatin to an average size of 400 basepairs. The sonicated chromatin was centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 7 minutes at 4°C. 20 μl of the sonicated chromatin was diluted with 380 μl of IP buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol). Immunoprecipitation was carried out with 4 μl of anti-Rpb3 antibody.

2.6 Permanganate footprinting in salivary glands

Permanganate footprinting in salivary glands was performed as previously described (25, 26), with the modification that 100 ng of DNA was used for each LM-PCR reaction.

2.7 Immunofluorescence analysis

Polytene chromosome squashes were prepared as previously described (27). 2 pairs of glands were used for each slide. Larvae were dissected in dissection buffer and transferred to 50 μl of Solution A (15 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 60 mM KCl, 15 mM spermine, 1.5 mM spermidine and 1% Triton X-100) for 30 seconds, followed by transfer to Solution B (15 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 60 mM KCl, 15 mM spermine, 1.5 mM spermidine, 1% Triton X-100 and 3.7% formaldehyde) for 30 seconds and final transfer to Solution G (50% glacial acetic acid). The glands were immediately transferred to a drop (9 μl) of Solution G on a siliconized coverslip and incubated for 3 minutes. A glass slide was placed over the coverslip and turned over so that tapping on the coverslip could spread the chromosomes. Once the chromosomes were sufficiently spread, the slide was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, the coverslip was removed and slide was stored in 95% ethanol overnight.

Staining of slides was carried out at room temperature. The slides were re-hydrated in TBST (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 0.03% Triton X-100) for 10 minutes and then washed once in TBST for 5 minutes. Blocking was carried out with 20 μl of blocking solution (10% Fetal Bovine Serum in TBST) at room temperature for one hour. The slides were then washed with TBST thrice for 5 minutes each. Primary antibodies were diluted in 10% FBS in TBST and 20 μl was used for staining of each slide. HDAC3 antibodies were used at 1:50 dilution and the antibodies were a gift from Dr Mattias Mannervik. Rpb3 antibodies were used at a 1:100 dilution. Staining with primary antibodies was carried out for 2 hours at room temperature. The slides were then washed thrice with TBST for 10 minutes each. Appropriate fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies were used at a 1:250 dilution and 20 μl was used per slide. The slides were incubated at room temperature for 90 minutes and then washed thrice with TBST. The slides were then washed with TBS containing 2 ng/ml Hoechst for 20 minutes and then washed with TBS for 20 minutes. The slides were then mounted onto a coverslip with 20 μl of mounting solution (100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.5), 80% glycerol, 2% n-propylgallate). Chromosome spreads were visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

3. RESULTS

3.1 RNAi-screening for factors that affect induction of an hsp70 reporter transgene

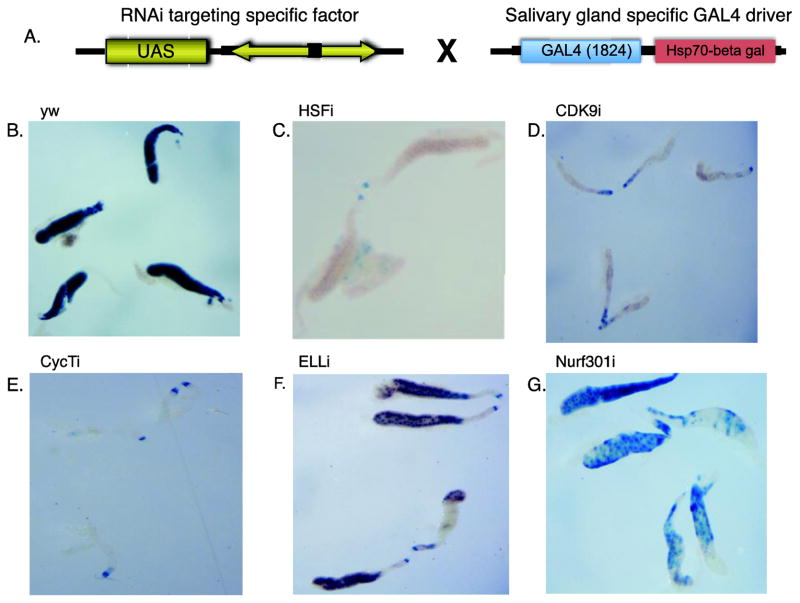

We developed an RNAi screen that allows one to harness the vast collection of Gal4 inducible RNAi fly lines available to the Drosophila community to identify proteins that function in expression of the hsp70 heat shock gene (9). We recombined a previously described hsp70 beta-galactosidase reporter gene known as Z243(28) onto a chromosome harboring a transgene that drives expression of Gal4 in salivary glands (Bloomington stock 1824) to generate the fly line we call yw; Z243, 1824. By mating this fly line to an appropriate Gal4 inducible RNAi fly line, we can deplete a selected protein from salivary glands and monitor the effects on the heat shock induction of the hsp70 beta-galactosidase reporter gene by incubating the glands with the inert chromogenic substrate X-gal and observing the development of blue pigment (Figure 1A). Salivary glands were chosen because they can be analyzed by immunofluorescence staining of polytene chromosomes or permanganate genomic footprinting to further investigate the basis for defects caused by knocking down specific proteins.

Figure 1. Inhibition of heat shock induction of an hsp70-beta gal reporter gene by depletion of specific factors targeted by RNAi in salivary glands.

(A) Schematic of the mating between an RNAi fly-line with a Gal4-regulated RNAi transgene and a fly containing an hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter gene (Z243) and a transgene expressing Gal4 (1824) in salivary glands. Third instar larvae from the mating were heat shocked for 30 minutes and then recovered at 22°C for 30 minutes. The dissected salivary glands were incubated in X-gal solution for 2 hours. (B) X-gal stained salivary glands from a control mating of yw with Z243,1824 flies.(C–G) X-gal stained salivary glands from larvae expressing RNAi against HSF, Cdk9, Cyc T, ELL, or Nurf301. Glands in all the panels were photographed at the same magnification. The size of the control glands can vary depending on the age and how crowded the vial of larvae is. Glands from the CDK9i and CycT9 progeny were consistently smaller than the control glands whereas glands from the other RNAi progeny fell within the size range observed for the control glands.

To evaluate the efficacy of this approach, we examined the impact of various RNAi expressed in salivary glands on the expression of the hsp70 reporter gene during heat shock (Figure 1). Heat shock causes the transcription factor HSF to bind the heat shock gene promoters and activate transcription (29). RNAi-mediated depletion of HSF almost completely inhibited heat shock induced expression of the hsp70 reporter gene (Figure 1, compare the control in panel B to the HSF-depleted glands in panel C). CDK9 and CycT are subunits of the kinase P-TEFb and are important for productive transcription elongation (7). RNAi against either of these subunits also inhibited induction of hsp70 (Figure 1 D–E). RNAi against ELL or Nurf301 partially inhibit induction of hsp70 (Figure 1 F–G). ELL is a transcription elongation factor that associates with Pol II and Nurf301 is a subunit of a chromatin-remodeling factor. Also, ELL resides in the super elongation complex, SEC, along with CDK9 and CycT (30). Both ELL and Nurf301 were previously shown to contribute to induction of hsp70(31, 32). Collectively, these results indicate that our screen is able to detect known regulators of hsp70.

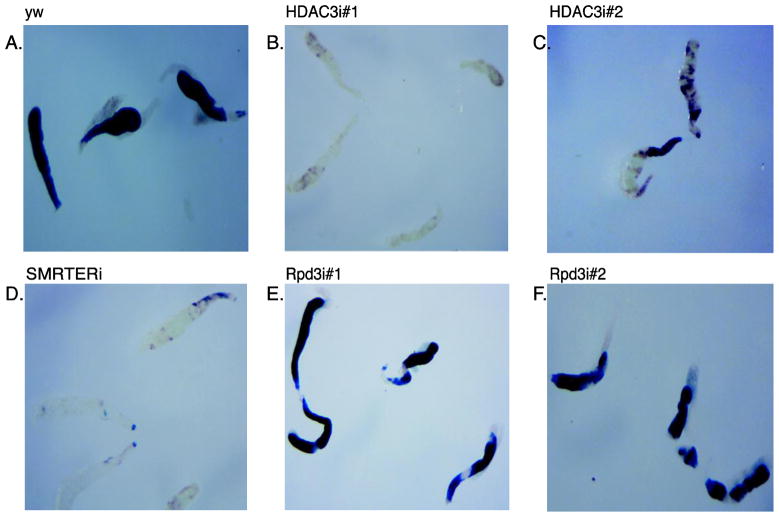

3.2 Depletion of HDAC3 and SMRTER inhibits heat shock induction of the hsp70 reporter gene

During the course of testing various RNAi, we observed that depleting the histone deacetylase HDAC3 greatly inhibited induction of the hsp70 reporter gene (Figure 2, compare panels A and B). This was surprising since HDACs are typically thought to repress transcription. We obtained similar results when we repeated the experiment with a second RNAi fly line denoted as HDAC3i#2 that targets a different region of HDAC3 (Figure 2C). This diminishes the possibility that the decrease in expression of the transgene is due to off-target effects of the RNAi. In vertebrates, HDAC3 is part of a complex with either of two paralogous hormone receptor corepressors known as NCoR or SMRT. Drosophila has a single homologous corepressor called SMRTER. RNAi against SMRTER also inhibited heat shock induction of the hsp70 reporter gene (Figure 2D). In contrast, RNAi against Rpd3 (HDAC1) did not inhibit induction of the hsp70 reporter gene (Figure 2 E–F).

Figure 2. Inhibition of heat shock induction of an hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter gene by depletion of specific factors targeted by RNAi in salivary glands.

(A) X-gal staining of salivary glands from a control mating of yw with Z243,1824 flies.(B–C) X-gal staining of salivary glands expressing different HDAC3 RNAi (HDAC3i#1 and HDAC3i#2). (D) X-gal staining of salivary glands expressing RNAi against the HDAC3-associated protein, SMRTER. (E–F) X-gal staining of salivary glands expressing different HDAC1 (Rpd3) RNAi. Glands in all panels of the figure were photographed at the same magnification. HDAC3i and SMRTERi glands were consistently larger than the control when first dissected, but shrunk when placed in the glycerol solution in which the glands were photographed.

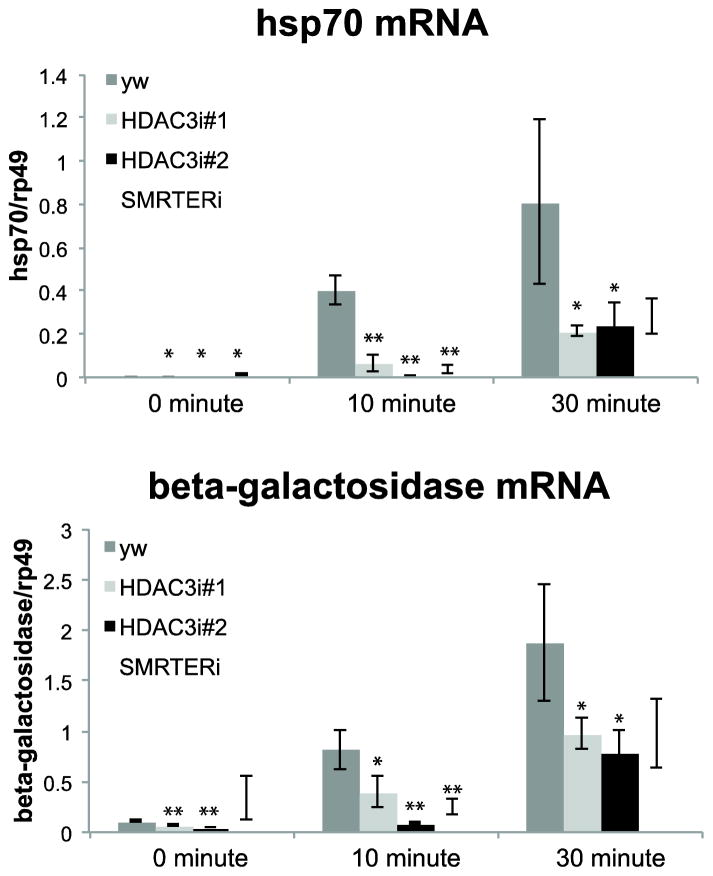

3.3 Depletion of HDAC3 or SMRTER inhibits hsp70 mRNA synthesis during heat shock

To determine if the RNAi against HDAC3 or SMRTER were inhibiting transcription of the hsp70-beta galactosidase transgene and the endogenous hsp70 gene, we measured the levels of mRNA produced after heat shock. Dissected salivary glands were heat shocked for 10 minutes or 30 minutes and RT-PCR was performed on RNA isolated from glands. Levels of endogenous hsp70 and hsp70-beta galactosidase transgene mRNA were reduced in HDAC3 and SMRTER depleted glands (Figure 3A, 3B).

Figure 3. Depletion of HDAC3 or SMRTER inhibits induction of hsp70.

Reverse transcriptase-qPCR analysis of endogenous hsp70 mRNA and hsp70-beta galactosidase transgene mRNA levels in salivary glands from RNAi lines targeting HDAC3, SMRTER or control (yw) larvae. For each case including yw, the female parent was Z243, 1824. Salivary glands were heat shocked at 37°C for 0, 10, or 30 minutes. Total RNA was isolated, followed by cDNA synthesis. hsp70 and Beta-galactosidase were detected by qPCR and expressed as a ratio relative a control gene, RP49, whose expression was unaffected by heat shock. Results are from three independent experiments and error bars represent SEM. * indicates a p-value <0.1, ** indicates a p-value <0.05 (t-test comparing control (yw) with individual RNAi samples).

The effect of the RNAi is more pronounced at 10 minutes of heat shock compared to 30 minutes as there is a 6 (HDAC3 depletion) or 10 (SMRTER depletion) fold reduction in the level of hsp70 mRNA after 10 minutes of heat shock whereas the reduction after 30 minutes of heat shock is about 3 fold relative to the control yw glands. The 3 fold decrease in mRNA level after 30 minutes of heat shock is similar to the 40% reduction in mRNA previously reported for Drosophila tissue culture cells treated with HDAC3 RNAi (33).

While there is a 3-fold decrease in mRNA in HDAC3 or SMRTER depleted salivary glands, the decrease in X-gal staining in these glands compared to the control is more pronounced (Figure 2). HDAC3 is also present in the cytoplasm (34) so it could impact additional steps in gene expression such as translation.

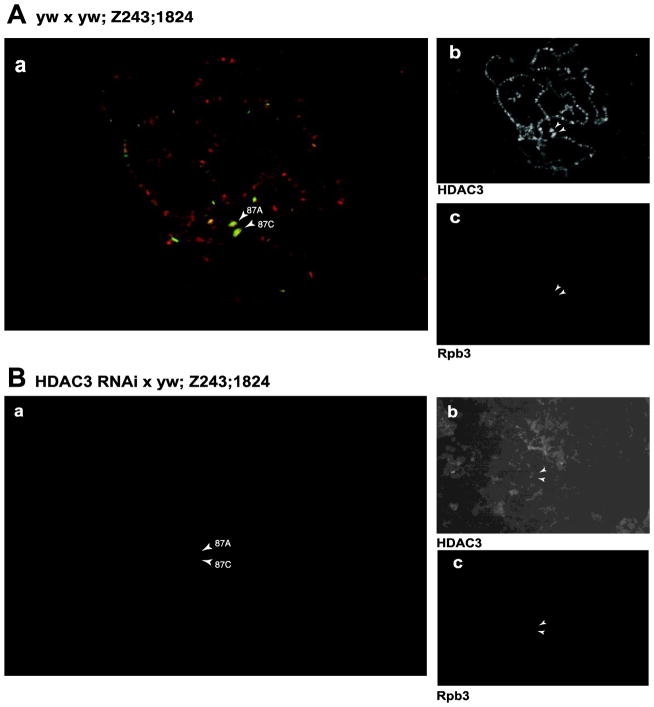

3.4 HDAC3 associates with the heat shock loci on polytene chromosomes during heat shock

Since HDAC3 depletion inhibited hsp70 expression, we determined if HDAC3 associates with the heat shock genes. Polytene chromosomes from heat-shocked larvae were incubated with antibodies against HDAC3 and Rpb3 (a subunit of RNA Pol II) followed by incubation with fluorescent secondary antibodies. Both HDAC3 and Pol II were detected at the heat shock puffs in control larvae (Figure 4A). In contrast, staining for HDAC3 was absent from heat shock puffs in HDAC3 depleted salivary glands, thus confirming that HDAC3 was depleted by its respective RNAi and that the immunofluorescence staining by the HDAC3 antibody in the control sample is indeed due to HDAC3 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Immunostaining of polytene chromosomes detects HDAC3 at heat shock puffs.

(A) Polytene chromosomes from salivary glands of control (yw x yw; Z243,1824) third instar larvae that were heat shocked for 10 minutes. (a) Overlaid image of staining for HDAC3 and Rpb3, a subunit of Pol II. Panels to the right show individual staining for HDAC3 (b) and Pol II (c). (B) Polytene chromosomes from salivary glands of HDAC3-depleted (HDAC3i x yw; Z243,1824) third instar larvae that were heat shocked for 10 minutes. (a) Overlaid image of staining for HDAC3 and Pol II in yw x yw; Z243, 1824 larvae. Panels to the right show individual staining for HDAC3 (b) and Pol II (c). HDAC3 was stained with an anti-guinea pig primary antibody (gift from M. Mannervik) at 1:50 dilution. Pol II was stained with anti-rabbit primary antibody against Rpb3, at a 1:100 dilution. The primary antibodies were visualized with an Alexa-568 conjugated anti-guinea pig and Alexa-488 conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. Arrows point to the heat shock loci at 87A and 87C where the copies of the hsp70 gene reside.

3.5 Depletion of HDAC3 reduces the level of Pol II on the hsp70 gene during heat shock

We were unable to detect a decrease in the level of Pol II associated with the puffs in HDAC3 depleted glands despite the decrease in mRNA. It is possible that not all of the Pol II at the locus is engaged in transcription. To quantify relative levels of Pol II associated with the hsp70 gene, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to monitor Pol II on the hsp70 gene in salivary glands under non-heat shock conditions and after 10 minutes of heat shock. Prior to heat shock induction, Pol II was concentrated at the promoter region (Figure 5A). This Pol II corresponds to the well-characterized Pol II that pauses in the promoter proximal region (35). While there appears to be slightly elevated levels of Pol II in the body of the gene in the HDAC3 depleted non-heat-shocked glands in comparison to the control, these Pol II molecules do not appear to be productive because no difference in the level of mRNA could be detected between nonheat shock samples from control and HDAC3 depleted glands (Figure 3).

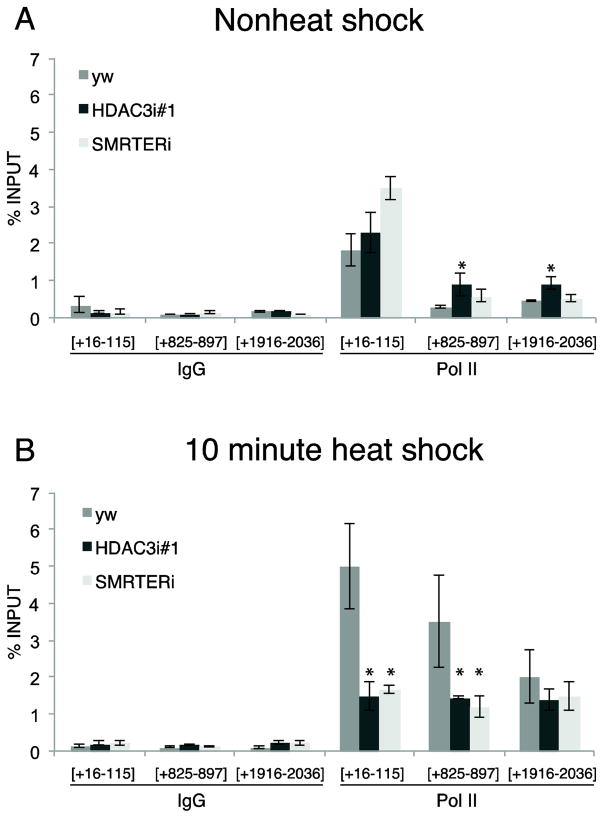

Figure 5. ChIP for Pol II in control, HDAC3 and SMRTER depleted glands.

ChIP for Pol II from salivary glands under non-heat shock conditions (A) or heat shocked for 10 minutes (B). Numbers on the x-axis represent the intervals of the amplicons relative to the transcription start site. The y-axis represents percentage of input that was recovered in the ChIP experiment. Error bars represent SEM of three independent experiments. * indicates p-value <0.03 (t-test comparing control (yw) with each individual RNAi samples).

The level of Pol II at the promoter and in the body of the gene of hsp70 increased significantly in control glands following a 10 minute heat shock (Figure 5B). This reflects the Pol II that is newly recruited to hsp70 and initiates transcription upon activation. Significantly less Pol II was present at the promoter and in the body of hsp70 in heat shocked glands depleted of HDAC3 or SMRTER than the control glands indicating that decrease in hsp70 mRNA produced during heat shock can in part be accounted for by diminished level of Pol II recruited to the promoter.

3.6 The rate of induction of hsp70 is not affected by depletion of HDAC3 or SMRTER

The ChIP results showed that during heat shock, the levels of Pol II in the promoter and the body of hsp70 in HDAC3 or SMRTER depleted glands were lower than in control glands. The difference in levels of Pol II could result from a change in the rate of induction and release of Pol II from the paused state upon activation in the RNAi samples. To evaluate if the rate of induction is affected by depletion of HDAC3 or SMRTER, we carried out permanganate footprinting on salivary glands at various times after heat shock.

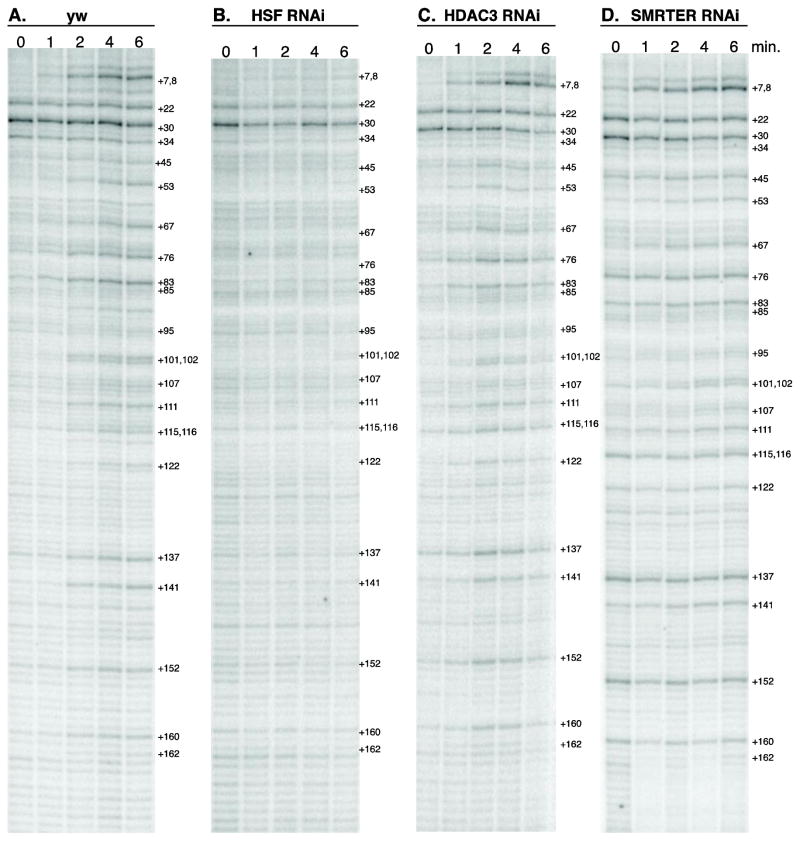

Permanganate footprinting detects transcriptionally engaged Pol II(26). Thymines in single stranded DNA are more reactive to oxidation by permanganate than thymines in double stranded DNA. In Drosophila, hyper-reactive thymines at +22 and +34 at the hsp70 promoter reveal the presence of paused Pol II. Upon heat shock, Pol II is released from the pause and transcribes into the body of the gene, as is seen by the increased permanganate reactivity at sites beyond the pause site, for example at +76, +101, and +102 (Figure 6A). In addition, thymines located at +7 and +8 increase reactivity due to reinitiation by Pol II. All of these heat shock-dependent changes in permanganate reactivity are prevented by depletion of HSF (Figure 6B), the DNA binding protein that activates the heat shock genes upon heat shock (6, 29).

Figure 6. Permanganate footprinting of the promoter proximal region of hsp70 in control, HDAC3 and SMRTER depleted glands.

Permanganate footprinting in salivary glands isolated from control (A), HSF depleted glands (B), HDAC3 (C) or SMRTER depleted glands (D). Dissected glands were heat shocked for the indicated number of minutes at the top of the gels (0,1,2,4,6 minutes). LM-PCR was carried out with primers corresponding to the promoter proximal region of hsp70 gene. Numbers flanking the right side of each panel designates nucleotide positions downstream from the transcription start site.

We observe no significant difference in the permanganate reactivity in HDAC3 or SMRTER depleted glands after various times of heat shock as compared to the control glands. This suggests that upon heat shock, paused Pol II is released and transcribes into the body of the gene irrespective of the depletion of HDAC3 or SMRTER and indicates that neither of the proteins affects the rate of induction. Moreover, since permanganate reactivity persists near the transcription start site, the rates of reinitiation are not affected by the loss of HDAC3 or SMRTER. Hence, HDAC3 appears to contribute to hsp70 expression at a point after HSF-mediated activation of paused Pol II and after subsequent rounds of reinitiation.

4. Discussion

4.1 RNAi screening for factors that affect heat shock induction of the hsp70 gene

The Drosophila heat shock system serves as a general model to investigate transcriptional regulation (8). To identify proteins involved in the induction of the hsp70 heat shock gene, we devised a directed screen for RNAi that impair heat shock induction of an hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter gene. We applied this screen to salivary glands by mating flies with the RNAi transgene to flies that contained a transgene that expresses Gal4 in salivary glands and another transgene that fuses the hsp70 promoter region to the coding sequence for beta-galactosidase. We validated the screen by showing that RNAi against several candidate proteins previously shown to contribute to induction of hsp70, also impaired expression of the hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter gene. We chose the hsp70-beta galactosidase reporter because previous studies indicated that it recapitulated the induction properties of the endogenous hsp70 gene (28, 29, 35).

Our screen complements tissue culture based screens by tapping into the large number of RNAi transgenic lines that are now available to the scientific community (9, 36). Lis and collegues (33) screened a wide spectrum of RNAi for their effects on induction of the endogenous hsp70 gene, and monitored levels of hsp70 mRNA synthesized following heat shock. They reported that RNAi against HSF, Cyc T, and ELL diminished heat shock induction by 95%, 80%, and 65% respectively, which is in agreement with the results of our screen. Also, as noted by others, we have observed cases where an RNAi appears to have greater efficacy in salivary glands than in tissue culture (37). Lis and collegues (33) reported that RNAi against NURF301 and HDAC3 diminished induction of hsp70 by 5% and 33%, respectively, whereas our screen revealed greater effects. These differences could be due to the choice of RNAi, the mechanisms for introducing the RNAi into cells, or the use of the hsp70-beta galactosidase transgene. In addition, since our assay depends on proper processing and export of the RNA as well as translation, RNAi-mediated defects in these steps will influence the level of reporter detected. Hence, it is important follow-up candidates that arise from the screen with more direct measurements of transcription.

4.2 Identification of HDAC3 as a positive effector of hsp70 transcription during heat shock

HDACs are most widely recognized as transcriptional repressors, but several studies provide strong evidence that they also function in transcriptional activation (for reviews, see (38–40)). Genomic studies have detected HDACs primarily at active genes (11, 41) and transcriptome analysis of cells depleted of specific HDACs reveals both increases and decreases in expression (18, 42). The mechanism by which HDACs stimulate transcription is largely unknown.

We found that depletion of HDAC3 severely impaired expression of our hsp70-beta-galactosidase reporter gene. Several observations argue that this is a consequence of the depletion of HDAC3 and not the result of an off-target effect of the HDAC3 RNAi. First, 2 different RNAi targeting different regions of the HDAC3 mRNA inhibited induction of the hsp70 reporter gene. Second, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy showed that HDAC3 was depleted from polytene chromosomes in larvae expressing HDAC3 RNAi. Third, depletion of SMRTER, a protein that forms a complex with HDAC3 and is required for HDAC3 activity (43, 44), also impairs induction of the hsp70 reporter gene.

Further analysis of how HDAC3 depletion inhibits expression of hsp70 revealed that HDAC3 has a positive effect on transcription. The level of mRNA synthesized during a 10 minute heat shock was approximately 4-fold lower in glands depleted of HDAC3. In accordance with this, there was approximately a 3-fold decrease in the level of Pol II detected in the promoter region by ChIP. The difference in Pol II densities diminished as we measured regions farther and farther downstream from the promoter. Pol II pauses at the ends of genes prior to termination and differences in the duration of this pause might contribute to the similarity in the steady state level of Pol II in the downstream regions (45).

We were unable to detect a corresponding decrease in Pol II at the hsp70 loci by immunofluorescence microscopy. Two things could be contributing to this apparent discrepancy. First our immunofluorescence technique is not as quantitative as our ChIP technique. Second, some of the Pol II detected at heat shock loci is probably not engaged with the DNA template. Instead, a portion of the Pol II that accumulates at puffs during heat shock appears to be bound to a network of poly ADP-ribose chains that forms at the heat shock loci during heat shock (23, 46).

We investigated the possibility that the depletion of HDAC3 delayed the induction of heat shock genes by monitoring with permanganate footprinting the behavior of Pol II in the promoter proximal region during the first several minutes of heat shock. We were unable to detect any reproducible differences between HDAC3 and control glands indicating that the depletion of HDAC3 does not delay the rate of induction. In addition, the depletion of HDAC3 did not appear to interfere with reinitiation since there were no differences in the levels of permanganate reactivity near the transcription start where reinitiating Pol II would reside.

Depletion of SMRTER appeared to affect pausing prior to heat shock induction because we observed an increase in the permanganate reactivity downstream from where Pol II normally pauses (compare annotated bands from +45 to +160 in the first lane of panels A and D in Figure 6). However, it is unlikely that this effect is related to HDAC3 since the behavior of Pol II in the HDAC3 depleted cells is similar to the control. SMRTER also associates with Rpd3 (47). Unfortunately, we were unable to investigate the effects of depleting Rpd3 on Pol II at the hsp70 gene because the small, fragile state of the glands made their isolation for permanganate footprinting intractable.

There is an apparent discrepancy between our permanganate footprinting data and ChIP data in that the latter showed 3-fold less Pol II in the promoter proximal region of HDAC3-depleted glands than control glands following heat shock whereas the footprinting did not detect any difference in the intensity of the permanganate reactivity as would be expected if the level of engaged Pol II were affected by the depletion of HDAC3. Inherent differences in the two techniques for monitoring Pol II could explain this discrepancy. Permanganate footprinting provides near single nucleotide resolution for regions where thymines report the presence of transcriptionally engaged Pol II. In contrast, chromatin immunoprecipitation provides a measure of the relative density of Pol II in a region spread over a few hundred nucleotides, since the average size of our sonicated DNA is 400 bp.

Understanding how HDAC3 functions as a positive effector of hsp70 transcription during heat shock requires more investigation. Our observations are similar to those first reported for GAL1 and INO1 in yeast where deletion of Hos2, a class I HDAC, severely impaired induction of these genes (12). These researchers proposed that histone deacetylation was required for transcription reinitiation. We surmise that HDAC3 is contributing to hsp70 expression at some point after the initial induction by heat shock since the kinetics of induction detected by permanganate footprinting was similar. The genomic distribution of five HDACs in Drosophila has been determined (48). HDACs 1, 4a, 6 and 11 were found to be concentrated in the vicinity of the transcription start site (TSS). In stark contrast, the level of HDAC3 detected near transcription start sites was significantly less than what was detected in the body of the gene. This supports the possibility that HDAC3 positively affects elongation once Pol II has cleared the promoter proximal region. However, HDAC3 certainly has other roles since it is present at numerous loci on polytene chromosomes that do not harbor Pol II (for example, see HDAC3 stained loci in Figure 4A).

Highlights.

We describe a screen for identifying proteins that affect hsp70 transcription

We identify HDAC3 and SMRTER as positive regulators of hsp70 expression

HDAC3 regulates hsp70 expression at step subsequent to activation of the paused Pol II by HSF

Acknowledgments

We thank Mattias Mannervik for providing antibody against Drosophila HDAC3. We thank Ali Shilatifard for providing the ELL RNAi fly line and John T. Lis for providing the Z243 fly line. This research was supported by NIH grant GM47477.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rougvie AE, Lis JT. The RNA polymerase II molecule at the 5′ end of the uninduced hsp70 gene of D. melanogaster is transcriptionally engaged. Cell. 1988;54:795–804. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C, Li X, Hechmer A, Eisen M, Biggin MD, Venters BJ, Jiang C, Li J, Pugh BF, Gilmour DS. NELF and GAGA factor are linked to promoter proximal pausing at many genes in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3290–3300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02224-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muse GW, Gilchrist DA, Nechaev S, Shah R, Parker JS, Grissom SF, Zeitlinger J, Adelman K. RNA polymerase is poised for activation across the genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1507–1511. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeitlinger J, Stark A, Kellis M, Hong JW, Nechaev S, Adelman K, Levine M, Young RA. RNA polymerase stalling at developmental control genes in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1512–1516. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lis J, Wu C. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling and trucking along. Cell. 1993;74:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni Z, Saunders A, Fuda NJ, Yao J, Suarez JR, Webb WW, Lis JT. P-TEFb is critical for the maturation of RNA polymerase II into productive elongation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1161–1170. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01859-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guertin MJ, Petesch SJ, Zobeck KL, Min IM, Lis JT. Drosophila heat shock system as a general model to investigate transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2010;75:1–9. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, Couto A, Marra V, Keleman K, Dickson BJ. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XJ, Seto E. Collaborative spirit of histone deacetylases in regulating chromatin structure and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Zang C, Cui K, Schones DE, Barski A, Peng W, Zhao K. Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell. 2009;138:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang A, Kurdistani SK, Grunstein M. Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science. 2002;298:1412–1414. doi: 10.1126/science.1077790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rundlett SE, Carmen AA, Kobayashi R, Bavykin S, Turner BM, Grunstein M. HDA1 and RPD3 are members of distinct yeast histone deacetylase complexes that regulate silencing and transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J. 2003;370:737–749. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow AL, van Drunen CM, Johnson CA, Tweedie S, Bird A, Turner BM. dSIR2 and dHDAC6: two novel, inhibitor-resistant deacetylases in Drosophila melanogaster. Exp Cell Res. 2001;265:90–103. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson CA, Barlow AL, Turner BM. Molecular cloning of Drosophila melanogaster cDNAs that encode a novel histone deacetylase dHDAC3. Gene. 1998;221:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeremski M, Stricker JR, Fischer D, Zusman SB, Cohen D. Histone deacetylase dHDAC4 is involved in segmentation of the Drosophila embryo and is regulated by gap and pair-rule genes. Genesis. 2003;35:31–38. doi: 10.1002/gene.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foglietti C, Filocamo G, Cundari E, De Rinaldis E, Lahm A, Cortese R, Steinkuhler C. Dissecting the biological functions of Drosophila histone deacetylases by RNA interference and transcriptional profiling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:17968–17976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lv WW, Wei HM, Wang DL, Ni JQ, Sun FL. Depletion of histone deacetylase 3 antagonizes PI3K-mediated overgrowth of Drosophila organs through the acetylation of histone H4 at lysine 16. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:5369–5378. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu CC, Bornemann DJ, Zhitomirsky D, Miller EL, O’Connor MB, Simon JA. Drosophila histone deacetylase-3 controls imaginal disc size through suppression of apoptosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhaskara S, Chyla BJ, Amann JM, Knutson SK, Cortez D, Sun ZW, Hiebert SW. Deletion of histone deacetylase 3 reveals critical roles in S phase progression and DNA damage control. Mol Cell. 2008;30:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi D, Bergman M, Aihara H, Nibu Y, Mannervik M. Drosophila Ebi mediates Snail-dependent transcriptional repression through HDAC3-induced histone deacetylation. The EMBO journal. 2008;27:898–909. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petesch SJ, Lis JT. Activator-induced spread of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase promotes nucleosome loss at Hsp70. Molecular cell. 2012;45:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zink D, Paro R. Drosophila Polycomb-group regulated chromatin inhibits the accessibility of a trans-activator to its target DNA. Embo J. 1995;14:5660–5671. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghosh SK, Missra A, Gilmour DS. Negative Elongation Factor Accelerates the Rate at Which Heat Shock Genes Are Shut off by Facilitating Dissociation of Heat Shock Factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4232–4243. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05930-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilmour DS, Fan R. Detecting transcriptionally engaged RNA polymerase in eukaryotic cells with permanganate genomic footprinting. Methods. 2009;48:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Champlin DT, Frasch M, Saumweber H, Lis JT. Characterization of a Drosophila protein associated with boundaries of transcriptionally active chromatin. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1611–1621. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon JA, Lis JT. A germline transformation analysis reveals flexibility in the organization of heat shock consensus elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2971–2988. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.7.2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boehm AK, Saunders A, Werner J, Lis JT. Transcription factor and polymerase recruitment, modification, and movement on dhsp70 in vivo in the minutes following heat shock. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7628–7637. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7628-7637.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo Z, Lin C, Shilatifard A. The super elongation complex (SEC) family in transcriptional control. Nature reviews. 2012;13:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nrm3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badenhorst P, Voas M, Rebay I, Wu C. Biological functions of the ISWI chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3186–3198. doi: 10.1101/gad.1032202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith ER, Winter B, Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of poised RNA polymerase II by the elongation factor ELL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8575–8579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804379105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ardehali MB, Yao J, Adelman K, Fuda NJ, Petesch SJ, Webb WW, Lis JT. Spt6 enhances the elongation rate of RNA polymerase II in vivo. EMBO J. 2009;28:1067–1077. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karagianni P, Wong J. HDAC3: taking the SMRT-N-CoRrect road to repression. Oncogene. 2007;26:5439–5449. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adelman K, Lis JT. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:720–731. doi: 10.1038/nrg3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni JQ, Markstein M, Binari R, Pfeiffer B, Liu LP, Villalta C, Booker M, Perkins L, Perrimon N. Vector and parameters for targeted transgenic RNA interference in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2008;5:49–51. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murawska M, Hassler M, Renkawitz-Pohl R, Ladurner A, Brehm A. Stress-induced PARP activation mediates recruitment of Drosophila Mi-2 to promote heat shock gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dovey OM, Foster CT, Cowley SM. Emphasizing the positive: A role for histone deacetylases in transcriptional activation. Cell cycle. 2010;9:2700–2701. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.14.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds N, O’Shaughnessy A, Hendrich B. Transcriptional repressors: multifaceted regulators of gene expression. Development. 2013;140:505–512. doi: 10.1242/dev.083105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith CL. A shifting paradigm: histone deacetylases and transcriptional activation. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2008;30:15–24. doi: 10.1002/bies.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Negre N, Brown CD, Shah PK, Kheradpour P, Morrison CA, Henikoff JG, Feng X, Ahmad K, Russell S, White RA, Stein L, Henikoff S, Kellis M, White KP. A comprehensive map of insulator elements for the Drosophila genome. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadiyala V, Patrick NM, Mathieu W, Jaime-Frias R, Pookhao N, An L, Smith CL. Class I Lysine Deacetylases Facilitate Glucocorticoid-induced Transcription. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:28900–28912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.505115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guenther MG, Barak O, Lazar MA. The SMRT and N-CoR corepressors are activating cofactors for histone deacetylase 3. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6091–6101. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6091-6101.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.You SH, Lim HW, Sun Z, Broache M, Won KJ, Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor co-repressors are required for the histone-deacetylase activity of HDAC3 in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwak H, Fuda NJ, Core LJ, Lis JT. Precise maps of RNA polymerase reveal how promoters direct initiation and pausing. Science. 2013;339:950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1229386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zobeck KL, Buckley MS, Zipfel WR, Lis JT. Recruitment timing and dynamics of transcription factors at the Hsp70 loci in living cells. Mol Cell. 2010;40:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagy L, Kao HY, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Negre N, Brown CD, Ma L, Bristow CA, Miller SW, Wagner U, Kheradpour P, Eaton ML, Loriaux P, Sealfon R, Li Z, Ishii H, Spokony RF, Chen J, Hwang L, Cheng C, Auburn RP, Davis MB, Domanus M, Shah PK, Morrison CA, Zieba J, Suchy S, Senderowicz L, Victorsen A, Bild NA, Grundstad AJ, Hanley D, MacAlpine DM, Mannervik M, Venken K, Bellen H, White R, Gerstein M, Russell S, Grossman RL, Ren B, Posakony JW, Kellis M, White KP. A cis-regulatory map of the Drosophila genome. Nature. 2011;471:527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature09990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]