Abstract

Objectives

We explored relationships between general religiousness, positive religious coping, negative religious coping (spiritual struggle), and affective symptoms among geriatric mood disordered outpatients, in the northeastern United States.

Methods

We assessed for general religiousness (religious affiliation, belief in God, private and public religious activity) and positive/negative religious coping, alongside interview and self-report measures of affective functioning in a diagnostically heterogeneous sample of n = 34 geriatric mood disordered outpatients (n = 16 Bipolar, n = 18 Major Depressive) at a psychiatric hospital in eastern Massachusetts.

Results

Except for a modest correlation between private prayer and lower Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores, general religious factors (belief in God, public religious activity and religious affiliation) as well as positive religious coping were unrelated to affective symptoms after correcting for multiple comparisons and controlling for significant covariates. However a large effect of spiritual struggle was observed on greater symptom levels (up to 19.4% shared variance). Further, mean levels of spiritual struggle and its observed effects on symptoms were equivalent irrespective of religious affiliation, belief, private and public religious activity.

Conclusions

Previously observed effects of general religiousness on (less) depression among geriatric mood disordered patients may be less pronounced in less religious areas of the United States. However, spiritual struggle appears to be a common and important risk factor for depressive symptoms, regardless of patients' general level of religiousness. Further research on spiritual struggle is warranted among geriatric mood disordered patients.

Keywords: Negative Religious Coping, Spirituality, Depression, Mania

Introduction

A considerable body of empirical literature reports links between religious involvement and lower levels of depressive symptoms in the general population, albeit with modest effect sizes [1, 2], and relationships between religion and affective symptoms appear to be particularly pronounced among the elderly. In Brazil, participation in social religious activities is associated with lower risk of depression among community-dwelling older adults [3], and several national and international studies from Europe have revealed similar trends both at the individual and national level [4, 5]. Among medical patients in the United States, private and public religious activity, as well as intrinsic religious involvement, have consistently been associated with lower severity of depressive symptoms [6, 7, 8] and increased speed of remission from clinical depression [9, 10]. This is not entirely surprising since more than two fifths of older adults in the U.S. report utilizing religious resources in times of distress [11], and it is well established that religion is an important resource in coping, generally speaking [12]. More recent research has examined the specific effects of religion on symptoms within clinical samples of geriatric psychiatric patients. Among inpatients, religious involvement has been tied to less severe depression, shorter lengths of stay, and greater life satisfaction [13], and intrinsic religiousness (motivation to engage in religion because of religious beliefs themselves and not extraneous factors) has predicted lower symptom levels [14]. Similarly, among depressed outpatients, religious service attendance has been tied to lower levels of suicidal ideation and emotional distress [15]. Thus, as a whole, the extant research suggests that religion – broadly conceptualized and defined – is a protective factor against depression.

However, it is also recognized that religion has negative as well as positive facets. For example, religion can be a context for the development and occurrence of spiritual struggle, which can be defined as any religious or spiritual belief, emotion or behavior that is emotionally maladaptive or dysfunctional (i.e., exacerbates distress and/or impairment). Spiritual struggle may include anger at God [16], religious guilt [17], belief that God is malevolent [18] and fear of Divine retribution [19]. Previous literature suggests that spiritual struggle commonly occurs in response to psychosocial stressors, including psychiatric symptoms themselves; hence this construct is commonly referred to as “negative religious coping” in the literature [20]. While spiritual struggle (aka negative religious coping) tends to occur less commonly than positive and adaptive forms of religion [21], it has been identified as an important risk factor for psychopathology including depression, hopelessness, and even suicidality in both medical [22] and psychiatric samples [23]. Further, recent findings suggest that in certain religious communities, spiritual struggle can precede and thus may be an etiological factor in the development of depression [24]. While one recent paper reported a moderate correlation (standardized beta = .43) between spiritual struggle (negative religious coping) and depressive symptoms in a sample of elderly patients receiving treatment for depression in the southern United States [25], limited attention has been paid to this domain in the study of geriatric mood disorders and more research is warranted [26]. In particular, it is unclear whether the effects or prevalence of spiritual struggles – or the effects of general religious involvement – might be mitigated in areas of the United States that are not particularly religious, or for geriatric patients who are less personally religious themselves.

We therefore sought to investigate associations between general religious involvement and spiritual struggle with mood symptoms among older adults with mood disorders at a psychiatric hospital in eastern Massachusetts (the third least religious State by importance of religion [27]). To enhance the ecological validity of study findings, we recruited a mixed sample of patients with both major depression and bipolar disorder (currently euthymic or depressed) and symptoms in the mild to moderate range. We administered a brief interview assessing for general religiousness, spiritual struggle (negative religious coping), and positive religious coping alongside clinical interview and self-report symptom measures, and we statistically evaluated relationships between these indices. We hypothesized that general religiousness and positive religious coping would predict lower symptom levels, and that spiritual struggle would be associated with greater levels of symptomatology in the sample.

Methods

Procedures

Thirty-four (n = 34) participants were recruited from ongoing research studies examining the course of mood disorders among older adults within McLean Hospital's Geriatric Psychiatry Research Program. All participants provided informed consent prior to the initiation of study procedures. Participants who endorsed serious or unstable medical conditions, history of substance abuse or dependence in the past 12 months, dementia, schizophrenia, psychotic, or seizure disorders, or those who were deemed unable to provide informed consent, were excluded from study participation. Non-English speaking referrals were also excluded. All participants were monitored for suicidal ideation during the interview process; no participants included in this study endorsed significant ideation or recent self-injury resulting in psychiatric hospitalization or residential treatment. The present investigation was approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Participants

Participants ranged in age from 55 to 89 years of age (M = 70.47; SD = 8.43) and 52.9% of subjects were female. All participants were White and had a high school degree; 85.2% had completed at least some college or post-high school education. All participants presented with symptoms meeting diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar (Type I, II, or Not Otherwise Specified), assessed by both a structured diagnostic assessment (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-Catie version) [28] and/or Mini- International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [29]), and interview by a board certified geriatric psychiatrist. The sample was roughly split between subjects carrying a diagnosis of Major Depression (n = 18; 52.9%) and Bipolar Disorder (n = 16; 47.1%). No subjects were actively manic, or receiving inpatient or residential treatment for any symptoms at the time of assessment. Mean age of onset for symptoms was 26.91 years (SD = 15.69) with a range of 6 to 63 years. Current functioning within the sample was relatively high in that the mean Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score was 67.44 (SD = 15.26) and all participants demonstrated sufficient cognitive functioning to complete the assessment in full. Participants' depressive and manic symptoms spanned the mild to moderate range (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sample Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| Gender | 53% Female (n = 18) |

| Age | M = 70.47; SD = 8.44 |

| Education (years) | M = 15.84; SD = 2.52 |

| Diagnosis | 47% Bipolar (n=16) |

| MADRS | M = 16.56; SD = 11.57 |

| GDS | M = 6.37; SD = 4.55 |

| YMRS | M = 3.76; SD = 3.25 |

| GAF | M = 67.44; SD = 15.26 |

Note: All subjects (n=34) were non-Hispanic Caucasian.

With regards to religious characteristics, roughly two thirds (67.6%) of the sample reported affiliation with an organized religion of which Catholicism was the mode (n = 13; 38.2%), and 47.1% of subjects reported certain belief in God whereas 23.5% reported no belief at all. Weekly attendance of religious services was reported by 20.6% of the sample (n = 7) and 17.6% (n = 6) reported daily private religious activity (e.g., prayer). These levels of religious involvement are low compared to the regional population, in that 60% of Massachusetts residents profess certain belief in God, 30% report weekly service attendance, and 41% report daily prayer [27]. Approximately one fifth of the sample reported no use of positive religious coping (n = 7, 20.6%) and about one half endorsed some level of spiritual struggle (n = 16, 47%). See Table 2 for a summary of the sample's religious characteristics.

Table 2.

Sample Spiritual/Religious Characteristics

| Religious Affiliation | Belief in God | Public Religious Activity | Private Religious Activity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic | n = 13 38.2% |

Very | n = 16 (47.1%) |

Less than 1×/week | n = 4 (11.7%) |

More than 1×/day | n = 1 (2.9%) |

| Christian1 | n = 7 20.6% |

Moderately | n = 6 (17.6%) |

1×/week | n = 3 (8.8%) |

1×/day | n = 5 (14.7%) |

| Jewish | n = 3 8.8% |

Fairly | n = 2 (5.9%) |

A few ×/month | n = 1 (2.9%) |

A few ×/week | n = 2 (5.9%) |

| Other | n = 1 2.9% |

Slightly | n = 2 (5.9%) |

A few ×/year | n = 8 (23.5%) |

1×/week | n = 1 (2.9%) |

| None1 | n = 10 29.4% |

Not at All | n = 8 (23.5%) |

1×/year or less | n = 8 (23.5%) |

A few ×/month | n = 6 (17.6%) |

| Never | n = 9 (26.5%) |

Rarely or Never | n = 19 (55.9%) |

||||

Notes:

Christian includes all non-Catholic Christian groups (Protestant, Episcopalian, Green Orthodox);

None includes Atheists and Agnostics

Measures

Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

The MADRS [30] is a clinical observation/interview assessment of severity and frequency of clinical depressive symptoms within the past week. Items are scored using anchors ranging on a continuous scale from 0 (symptoms absent) to 6 (continuous and/or debilitating), in respect to ten common symptoms of depression (apparent sadness, reported sadness, inner tension, reduced sleep, reduced appetite, concentration difficulties, lassitude, inability to feel, pessimistic thoughts, and suicidal thoughts). Total scores on the MADRS thus range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating a more serious depressive episode (e.g., requiring immediate care or hospitalization). A score of 0 indicates the absence of any depressive symptoms. The MADRS was completed by trained research assistants, under the supervision of a board certified geriatric psychiatrist.

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

The GDS [31] is a 15-item self-report measure, which was designed to specifically assess for depressive symptoms in geriatric populations. Subjects are asked to endorse either present (“Yes”) or absent (“No”) in response to a list of common symptoms of depression (including some reverse-score items) within the past week; example items include “Are you in good spirits most of the time?”, “Do you often feel helpless?”, and “Do you feel full of energy?” Endorsements of depressive symptoms are coded as 1, and thus total scores range from 0 to 15 with higher scores indicating greater depression severity.

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)

The YMRS [32] is a clinical observation-interview assessment to measure the frequency and severity of manic symptoms over the past week. Anchors are continuously coded from 0 (absent) to either 4 or 8 (highly present), on eleven items of manic symptoms (elevated mood, increased motor activity/energy, sexual interest, sleep, irritability, rate and amount of speech, language-thought disorder, content disorder, disruptive-aggressive behavior, appearance, and insight). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with a score of 0 indicating the absence of all mania symptoms and higher scores signifying greater mania. Like the MADRS, YMRS assessments were also completed by trained research assistants, under the supervision of a board certified geriatric psychiatrist

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF)

The GAF [33] rates overall psychological functioning, absent of physical and environmental limitations, on a scale 0 to 100. While the range is continuous, examples of functional impairment are provided in ten-point increments (e.g., 41 to 50 “serious symptoms… or any serious impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning,” 71 to 80 “If symptoms are present, they are transient and expectable reactions to psychosocial stressors…no more than slight impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning,” and 91 to 100 “superior functioning in a wide range of activities… no symptoms”). This assessment was completed by trained research assistants and/or a board certified geriatric psychiatrist.

General Religiousness

A series of four items assessed for general religiousness: (1) Religious affiliation was assessed with a single item and responses were coded as either affiliated or not affiliated; (2) Belief in God was assessed with the question “To what extent do you believe in God?” with a 5-point Likert-type response scale (Anchors ranging from “Not at All” to “Very”); (3) Frequency of public religious activity was measured by the question “How often do you attend church or other religious services?” (Anchors ranging from “Never” to “More than once/wk”); and (4) Frequency of private religious activity was assessed with the question “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or Bible study?” (Anchors ranging from “Rarely or Never” to “More than once a day”). It should be noted that the latter two items (frequency of public/private religious activity) were culled from the Duke Religion Index [34].

Positive Religious Coping

Patients completed the Brief RCOPE [35], a widely-utilized measure that assesses for use of religious coping strategies using a 4-point Likert-type scale. The Brief RCOPE is a well-validated measure and inter-item reliability for the scale in the present sample was high (α = .87). Of the Brief RCOPE's 14-items, seven assess for positive religious coping such as spiritual support/connection (e.g., Looked for a stronger connection with God) and benevolent religious reappraisals (e.g., Tried to see how God might be trying to strengthen me) in response to negative life events.

Spiritual Struggle (Negative Religious Coping)

The remaining seven Brief RCOPE items assess for spiritual struggle, such as punishing God reappraisals (e.g., Questioned God's love for me) and interpersonal spiritual tension (e.g., Wondered whether my church had abandoned me).

Analytic Plan

In order to avoid Type-I and Type-II error inflation, a combination of univariate and multivariate analytic approaches was utilized iteratively. We began by examining for the presence of covariates in the dataset with univariate Analyses of Variance (ANOVA) and tests of bivariate correlation among demographic and study variables. This analysis revealed that age and gender were unrelated to both religious and symptom factors. Further, unipolar depressed and bipolar patients did not report different levels of religious involvement, religious coping or spiritual struggle (p > .05), or symptoms except that unipolar depressed patients reported slightly higher GDS scores than bipolar patients (t(32) = 9.0, p < .006). We then conducted an omnibus Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) test to examine associations between six latent religious variables (belief in God, frequency of private prayer, frequency of public religious involvement, positive religious coping, and spiritual struggle) and three latent symptom variables (MADRS, GDS and YMRS). Significant relationships were then followed-up with additional regression tests controlling for covariates. Finally, we conducted additional bivariate correlation and regression analyses to explore levels of spiritual struggle across the range of religious involvement in the sample, and the relevance of spiritual struggle to symptoms controlling for general religiousness. Bonferroni correction was utilized when making multiple comparisons.

Results

General Religious Involvement and Symptoms

In our omnibus MANOVA test, belief in God and frequency of public religious activity were not associated with symptom levels in the sample (MADRS, GDS and YMRS scores), however a significant multivariate effect was observed for frequency of private religious activity. Follow-up bivariate analyses revealed that private religious activity was associated with lower GDS scores only (r = -.42, p < .05)1. Additional tests revealed that patients who prayed daily (n = 6) reported lower GDS scores than those who did not (t(28) = 4.65, p < .05). However, non-significant results emerged in additional tests comparing religiously affiliated and unaffiliated subjects, those who engaged in public prayer weekly versus less frequently, and participants with “certain” belief in God versus those with lower levels of belief or no belief. As a whole, these results suggest that general religious involvement was not significantly related to affective symptoms within the present sample, with the exception of an association between private prayer and lower GDS scores. See Table 3.

Table 3. Bivariate Correlations between General Religious Involvement and Symptoms.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Affiliation | - | ||||||

| 2) Belief in God | .71** | - | |||||

| 3) Public Religious Activity | .30 | .55** | - | ||||

| 4) Private Religious Activity | .45** | .54** | .58** | - | |||

| 5) MADRS | -.38* | -.22 | -.30 | -.34* | - | ||

| 6) GDS | -.30 | -.28 | -.30 | -.42* | .87** | - | |

| 7) YMRS | -.05 | .13 | .26 | .24 | .24 | .11 | - |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | .67 | 2.59 | 2.79 | 2.15 | 16.56 | 6.37 | 3.77 |

| Standard Deviation | .47 | 1.67 | 1.69 | 1.64 | 11.57 | 4.54 | 3.25 |

| Range | 0-1 | 0-4 | 1-6 | 1-6 | 0-40 | 0-13 | 0-12 |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

Cells represent Pearson correlations (r) for two-tailed uncorrected tests; Higher scores represent higher values of each variable (e.g., greater belief in God, greater frequency of public/private religious activity, higher levels of symptoms); Affiliation dummy coded as 1 = affiliated, 0 = unaffiliated; Correlation between private religious activity and MADRS scores was non-significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Spiritual Struggle, Positive Religious Coping and Symptoms

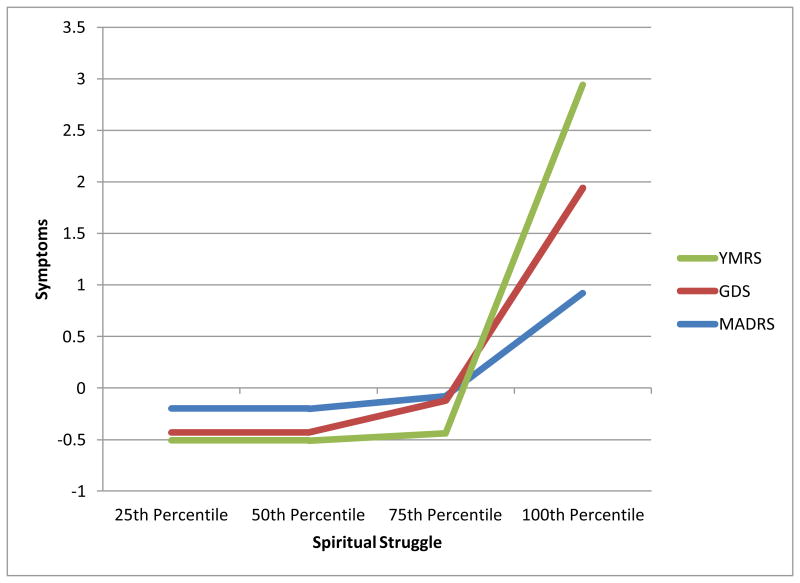

Our MANOVA test also identified a significant association between symptom factors and spiritual struggle, but not positive religious coping. An examination of bivariate correlations revealed that spiritual struggle was strongly associated with greater MADRS (r = .37, p < .05), GDS (r = .41, p < .05) and YMRS (r = .35, p < .05) scores. By contrast, a non-significant relationship between positive religious coping and MADRS, GDS and YMRS scores was confirmed (rs ranging from -.26 to .16, ns for all tests). Surprisingly, we also found that spiritual struggle was not higher among subjects with greater general religious involvement; levels of spiritual struggle were independent of religious affiliation (t(32) = 0.65, ns), belief in God (r = .15, ns), frequency of public religious activity (r = .01, ns), and frequency of private religious activity (r = .13, ns). Further, in partial correlations and regressions, spiritual struggle remained a robust predictor of greater symptoms even after controlling for general religious factors, accounting for 19.4%, 17.7% and 12.5% of the variance in MADRS, GDS and YMRS scores respectively. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Affective Symptoms as a function of Spiritual Struggle.

Note: Standardized scores of MADRS, GDS and YMRS are presented along the Y-axis; Percentile scores of Spiritual Struggle (Negative Religious Coping) scores are presented along the X-axis. As reported in text, bivariate relationships between Spiritual Struggle and all three symptom scales were significant controlling for general religious factors (religious affiliation, belief in God, and frequency of public/private religious activity).

Discussion

In the present investigation, religious affiliation, belief in God, and frequency of religious service attendance were all unrelated to affective symptoms, although private prayer was moderately associated with lower levels of self-reported depression as measured by the GDS. These findings are inconsistent with previous research, which has suggested that general religious belief and practice can buffer against depressive symptoms among older adults in both community and clinical settings. One explanation for this disparity is that previous research has largely been conducted within the southern United States, where religion is more part and parcel of the general culture, whereas the present study was conducted in one of the least religious enclaves of the country – eastern Massachusetts. To this end, it is possible that lower levels of religious culture may decrease the clinical relevance of specific religious factors – particularly community-based variables such as affiliation and public prayer – to affective symptoms. Indeed, recent research suggests that a general religious context is an important moderator of ties between specific religious factors and mental health [36]. Nevertheless, the significant relationship between private prayer and lower self-reported depression in our sample (within 17.6% shared variance) suggests that the interplay of general and specific religious factors on mental health is complex. Further research on moderators of religion-mental health ties deserves additional attention in future studies with larger samples, in order to inform more comprehensive and widely applicable models of relationships between religion and mental health.

Despite the fact that positive religious coping was unrelated to affective symptoms in this study, spiritual struggle (negative religious coping) was a strong predictor of greater symptoms of both depression and mania, with large effect sizes. This broadly speaks to the potential clinical as well as statistical relevance of spiritual struggle to geriatric mood disordered patients. We also observed that levels of spiritual struggle were highly common in that they were endorsed to at least some degree by 47% of the sample. More importantly, and surprisingly, levels of spiritual struggle were equivalent irrespective of subjects' belief in God, frequency of private/public religious involvement, or religious affiliation. While research in community settings suggests that spiritual struggle can occur among non-religious individuals [16], the high prevalence of spiritual struggles in this sample of mood disordered patients is noteworthy. Finally, we observed that the effects of spiritual struggle on (greater) symptoms remained statistically significant with a large effect size even after controlling for general religiousness (i.e., religious affiliation, belief in God, and frequency of public/private prayer). As such, both the prevalence and effects of spiritual struggle were substantial for religious and irreligious patients.

Several important clinical implications emerge from these intriguing findings. First, given the degree of shared variance between spiritual struggle and mood symptoms (ranging from 12.2% to 19.4%), clinical interventions to directly address spiritual struggle in this population may be warranted. Second, our findings highlight the importance of assessing for spiritual struggle in clinical practice with this population regardless of patients' general levels of spiritual or religious involvement. Third, and most importantly, it should not be assumed that a lack of general religious involvement precludes significant overlap between specific spiritual factors and mood symptoms. However, it must also be noted that this study was limited in that participants were outpatients reporting only mild to moderate levels of mood symptoms. Inclusion of participants with both lower and higher (acute) levels of symptomatology would have allowed for a better examination of the specific relationships between spiritual struggles and mood symptom. In this regard, it would be interesting for future studies to investigate relationships between spiritual struggles and mood symptoms more broadly, across a wider spectrum of affective functioning

As a cross-sectional investigation, the present study cannot provide insight into direction of effects between spiritual struggle and depressive/manic symptoms within the sample. It is possible that spiritual struggle represents a maladaptive cognitive bias that exacerbates affective symptoms, and it may even represent an independent etiological factor in the onset and maintenance of mood disorders. However, it is also possible that affective symptoms are a context for the development of distorted religious cognitions that are characteristic of spiritual struggle, or that spiritual struggle and affective symptoms share cognitive, affective, behavioral, or even genetic or neural diatheses. Further research to explore all of these possibilities using longitudinal and experimental research methods, and biomarkers of depression and other psychiatric symptoms, is warranted. Additional limitations of this study include a lack of ethnic diversity in the sample, a small (though adequately powered) sample size, a limited range of symptom severity, and heterogeneity of diagnoses – though the latter served to increase ecological validity of the findings. Nevertheless, the degree of shared variance between spiritual struggle and depression/mania within our sample, and the independence of this relationship from general religious involvement is noteworthy. Furthermore, the geographic locale of the present study and relatively irreligious sample overall provided for a conservative estimate of effects between spiritual struggle and symptoms. Thus, as a whole, the findings of this study may have implications for treatment of geriatric mood disordered patients, in that they suggest that spiritual struggles should be routinely assessed for in the context of clinical practice.

Key Points.

In our sample of mood disordered older adults in Eastern Massachusetts, general religious involvement was not associated with symptoms. However, spiritual struggle was robustly related to elevated levels of depression and mania, even after controlling for religious involvement – suggesting that spiritual struggle may be an important risk factor for mood disorders regardless of patients' general level of religion. This study was limited by a limited range of mood symptoms in our sample.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Steven Pirutinsky (Columbia University) for his assistance with this manuscript. David H. Rosmarin, Ph.D. had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analyses. Financial support for this study was received from the Gertrude B. Nielsen Charitable Trust, the Rogers Family Foundation, National Institute of Mental Health (K23 077287-01A2) and the Harvard Catalyst Pilot Grant Program.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Private religious activity was also associated with lower MADRS scores (r = -.34, p < .05), however this relationship was non-significant after Bonferroni correction.

References

- 1.Smith TB, McCullough M, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:614–636. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullough ME, Larson DB. Religion and depression: A review of the literature. Twin Research. 1999;2:126–136. doi: 10.1375/136905299320565997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blay SL, Batista AD, Andreoli SB, Gastal FL. The relationship between religiosity and tobacco, alcohol use, and depression in an elderly community population. Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2008;16:934–943. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181871392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braam AW, Van den Eeden P, Prince MJ, et al. Religion as a cross-cultural determinant of depression in elderly Europeans: Results from the EURODEP collaboration. Psychol Med. 2001;31:803–814. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braam AW, Beekman ATF, van Tilburg TG, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W. Religious Involvement and Depression in Older Dutch Citizens. Soc Psychiat and Psychiatr Epid. 1997;32:284–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00789041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig HG. Religious attitudes and practices of hospitalized medically ill older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:213–224. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199804)13:4<213::aid-gps755>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koenig HG. Religion and Depression in Older Medical Inpatients. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;15:282–291. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000246875.93674.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musick M, Koenig H, Hays J, Cohen H. Religious activity and depression among community-dwelling elderly persons with cancer: The moderating effect of race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B:S218. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig HG, George L, Peterson B. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:536–542. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenig HG. Religion and remission of depression in medical inpatients with heart failure/pulmonary disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:389–395. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31802f58e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenig HG, George LK, Siegler IC. The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. Gerontologist. 1988;28:303–310. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: The Theory, Research, Practice. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baetz M, Larson D, Marcoux G, Bowen R, Griffin R. Canadian psychiatric inpatient religious commitment: An association with mental health. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:159–166. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payman V, George K, Ryburn B. Religiosity of depressed elderly inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:16–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H, Cheal K, McDonel Herr E, Zubritsky C, Levkoff S. Religious participation as a predictor of mental health status and treatment outcomes in older persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:144–153. doi: 10.1002/gps.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exline JJ, Park CL, Smyth JM, Carey MP. Anger toward God: Social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100:129–148. doi: 10.1037/a0021716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Exline JJ, Yali AM, Sanderson WC. Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:1481–1496. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200012)56:12<1481::AID-1>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Mahoney A. The role of religiousness in anxiety, depression and happiness in a Jewish community sample: A preliminary investigation. Ment Health, Relig and Cult. 2009;12:97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pargament KI, Murray-Swank N, Magyar G, Ano G. Spiritual struggle: A phenomenon of interest to psychology and religion. In: Miller WR, Delaney H, editors. Judeo-Christian perspectives on psychology: Human nature, motivation, and change. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2005. pp. 245–268. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McConnell KM, Pargament KI, Ellison CG, Flannelly KJ. Examining the links between spiritual struggles and symptoms of psychopathology in a national sample. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:1469–1484. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Ironson D, et al. View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. J Behav Med. 2011;34:414–425. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosmarin DH, Bigda-Peyton JS, Ongur D, Pargament KI, Björgvinsson T. Religious coping among psychotic patients: Relevance to suicidality and treatment outcomes. Psychiat Res. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.023. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Midlarsky E. Does negative religious coping accompany, precede, or follow depression among Orthodox Jews? J Affect Disorders. 2011;132:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bosworth HB, Park KS, McQuoid DR, Hays JC, Steffens DC. The impact of religious practice and religious coping on geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:905–914. doi: 10.1002/gps.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braam AW, Beekman ATF, van Tilburg W. Religiositeit en depressie bij ouderen: een overzicht van recent empirisch onderzoek [Religiosity and depression in later life: a review of recent epidemiological research] Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 2003;45:495–505. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. How Religious Is Your State? [June 19, 2013];Pew Forum. www.pewforum.org/How-Religious-Is-Your-State-.aspx. Published December 21 2009.

- 28.Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, et al. The National Institute of Mental Health clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) project. Schizophr Bull (Bp) 2003;29:15–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams JBW, Kobak KA. Development and reliability of a structured interview guide for the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (SIGMA) Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:52–58. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E, Evans S, Katona C. Screening, detection, and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders I: The acceptability and performance of the 15 item geriatric depression scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract. 1994;11:260–266. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig HG, Meador K, Parkerson G. Religion index for psychiatric research: A 5-item measure for use in health outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Holt CL. Does social support mediate the moderating effect of intrinsic religiosity on the relationship between physical health and depressive symptoms among Jews? J Behav Med. 2011;34:489–496. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]