Abstract

In late 2007 the Homeless Youth Alliance (HYA), a small non-profit serving homeless youth in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood of San Francisco, USA, attempted to move its needle exchange service from a site on the Haight street commercial strip to a community centre approximately 150 m away. The reaction of the housed community in the area was vocal and organized, and attracted considerable regional media attention. Ultimately, the plan to move the service had to be cancelled. The authors were, respectively, board chair and executive director of HYA at the time, and collected extensive field notes and media records as events unfolded.

In this paper, we re-examine these events through literatures on contested spaces and on ‘Not In My Backyard’ (NIMBY) resistance to social services. We found that opposition to the service relocation had little to do with opposition to needle exchange itself, but rather was symptomatic of broader contestation over the identity and character of the neighbourhood. On the one hand, the neighbourhood had experienced skyrocketing housing prices over the past 40 years, making home ownership almost exclusively the province of the wealthy. On the other, the neighbourhood retains historic connections to the 1968 ‘Summer of Love’, and the main commercial strip forms the centre of an active injecting drug use scene. As a consequence, many home owners who felt they had made considerable sacrifices to afford to live in the area expressed a sense of being “under siege” from drug users, and also believed that the City government pursues a deliberate policy of “keeping the Haight weird” by supporting ongoing service provision to drug users in the area.

Housed residents responded to this situation in a variety of ways. One response was to engage in what we term ‘defensive place making’, in which a small part of a broader neighbourhood is reimagined as “a different neighbourhood”. HYA’s attempt to move from its current location to this ‘different neighbourhood’ was thus perceived as an “invasion” which threatened to break down a tentatively established separate identity.

We conclude with a discussion of the relevance of these events for understanding and mitigating community opposition to services for drug users elsewhere.

Keywords: Space and place, Homelessness, Needle exchange, NIMBY

Introduction

In late 2007 the Homeless Youth Alliance (HYA), a small non-profit serving homeless youth in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood of San Francisco, USA, attempted to move its needle exchange service from a site on the Haight street commercial strip to a church community centre approximately 150 m away. The reaction of the housed community in the area was vocal and organized, and attracted considerable regional media attention. Ultimately, the plan to move the service had to be cancelled. The authors were, respectively, board chair and executive director of HYA at the time. In the aftermath of these events, while collating publicly available documentation and our own records, we came to realize that at least some of our assumptions about what had been driving opposition to the move were not well supported. We therefore sought to better understand ‘what just happened’ by reexamining events through a systematic analysis of available records and through the relevant literature from the fields of sociology, anthropology, and geography. Our guiding question was how do different notions of the meaning of a place shape debates about the location of public services.

Many types of social and physical infrastructure are generally agreed to contribute to the public good, yet face opposition from local communities when a specific location for a new service is proposed, a phenomena commonly referred to as ‘NIMBYism’ (‘Not In My Back Yard’). Despite decades of research demonstrating their public health efficacy (MacDonald, Law, Kaldor, Hales, & Dore, 2003; Wodak & Cooney, 2006), services that provide needles to people who inject drugs remain controversial, and it is common to encounter NIMBYism when planning new distribution locations. A common assumption among supporters of needle exchange (and our main assumption as the events described in this paper began) is that such NIMBYism is due to community framing of drug use as a moral problem rather than a public health problem, such that needle exchange becomes inappropriate ‘enabling’ of inherently problematic behaviours.

A limited literature on NIMBYism related to the provision of services to people who use drugs exists. A closely related literature additionally deals with services for other populations who are often, justifiably or not, associated with people who inject drugs (such as the homeless and people living with HIV/AIDS). This literature in combination suggests that the role of client characteristics can shape community response to social service delivery. In particular, several scholars have noted that resistance to proposed services increases as the ‘social acceptability’ of the clients of the service decreases, with drug users being located as among the most ‘unacceptable’ clients (Colón & Marston, 1999; Dear, 1992; Dear & Gleeson, 1991; Law & Takahashi, 2000; Lyon-Callo, 2001). Other authors, such as Wilton (1998), use psychological theory in an attempt to explain how stigmatized groups might become ‘the other’ to be excluded from a community. In addition, other scholars have argued that ‘policy narratives’ and the ways in which they frame social problems and their solutions can affect the acceptability of needle exchange and related services (Fitzgerald, 2013; Shaw, 2006; Tempalski, 2007). Finally, others locate NIMBY resistance to services as an attempt by communities to avoid being ‘stained’ by an association with a stigmatized population or activity (Law & Takahashi, 2000; Smith, 2010; Strike, Myers, & Millson, 2004; Takahashi, 1997, 1998; Takahashi & Dear, 1997).

As will be described below, what emerged as events unfolded was a complex contestation over competing visions of what the neighbourhood was and would be, a contestation in which the presence or absence of a needle exchange validated or invalidated the legitimacy of one or another sets of meanings ascribed to the place. As such, the issues raised in the existing NIMBY literature only partially explained events. In this paper, we extend this literature to describe how broader arguments about the character and future of a neighbourhood can play a significant role in NIMBY opposition, even in contexts where needle exchange itself is not necessarily conceptually opposed.

Background

The Haight

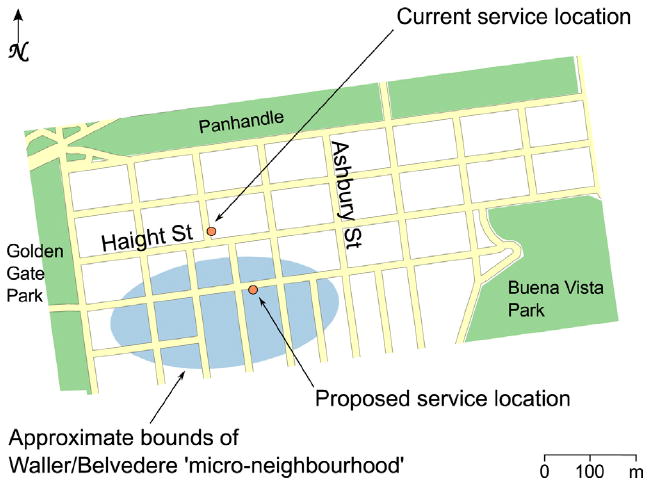

Before beginning, some background material on the history of the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood of San Francisco is needed to provide context for the events described. Geographically, the neighbourhood is centred on Haight Street, and extends from Golden Gate Park in the West to Buena Vista Park in the East, and from the Panhandle on the North to an arbitrary five or six streets South of Haight Street (see Fig. 1). The neighbourhood came into existence in the 1880s following the development of the adjacent 4.1 km2 Golden Gate Park, itself created in a deliberate attempt by property developers to draw home buyers to the then almost uninhabited Western side of San Francisco peninsula (Brechin, 1999). After the arrival of light rail connecting the Park with the central city in 1883, the Haight rapidly transitioned from farmland and sand dunes into an upper-middle class residential neighbourhood, featuring large Victorian-style houses and a small commercial strip. In 1906, the Haight was spared the fires following a large earthquake, leaving the neighbourhood with one of the largest collections of extant Victorian architecture in the City. During the Great Depression of the 1930s however, many of the middle-class residents left the area, and in the immediate postwar years large numbers of Victorian style houses were converted from single family housing into apartments and boarding houses. By the 1950s, City planners came to regard the area as ‘irredeemably blighted.’ The Victorian style of architecture had dropped out of fashion and was regarded as excessively expensive to maintain, and City planners suggested ‘revitalization’ programs which amounted to wholesale demolition and redevelopment. These plans, along with a postwar plan to route a freeway through the area, were never carried out due to a combination of lack of funding and the emergence of significant community opposition (Phillips, 1978).1

Fig 1.

In the late 1960s, large numbers of young people came to San Francisco attracted by the presence of new social and cultural movements, culminating with the Summer of Love in 1968. The Haight’s by then extremely low rents and the proximity to Golden Gate Park led to the area becoming one of the geographical centres for the cluster of social and cultural activities around which young people arranged themselves. Golden Gate Park served as both a venue for large events and, as during the Great Depression and the weeks immediately after the 1906 earthquake, a space for people without other housing options to camp. A range of services emerged to meet the basic food, shelter, medical and social needs of those who found themselves needing assistance, with the most notable, such as the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, being those developed and structured in whole or in part by those from the newly emerged community which they served (Smith & Luce, 1971; Staller, 2006).

In the 1970s and 1980s the area stagnated again, with many of the commercial spaces along Haight street being boarded up (Smith & Luce, 1971, p. 3ff). City Hall continued efforts to ‘revitalize’ the area through low interest redevelopment loans to property owners (Phillips, 1978, p. 61), however by the mid-1970s opposition to developer-oriented growth policies throughout the city led to the emergence of an anti-development ‘progressive’ political coalition which captured the Mayorship in 1975 and has continued to be a dominant force in city politics ever since (Beitel, 2004).

By the early 1990s, San Francisco had become a central location to another social and economic phenomena, the first dot-com boom. The Haight, like much of San Francisco, experienced skyrocketing property and rental prices throughout the 1990s and 2000s. As a consequence, newly arrived residents tended to be considerably wealthier than those who had moved to the area in earlier decades, and as with the middle-class house buyers of the 1880s, these newer arrivals were also drawn to the area by the close proximity of Golden Gate Park, as well as by the once again fashionable Victorian architecture. However, despite this partial return to gentility, the commercial strip along Haight Street remains a chaotic and internationally famous destination for both tourists and homeless young people seeking some vestige of the Summer of Love. As in the 1930s and 1960s, the adjacent Golden Gate Park has continued to provide shelter to a sizeable homeless population, who pursue economic activities such as panhandling (begging) and drug sales along the commercial strip alongside faux hippie-style stores and newer high-end boutiques.

Needle exchange in the Haight

In common with many other areas in the United States affected by the arrival of HIV in the 1980s, the distribution of clean needles to people who inject drugs in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood began as an illegal service conducted by drug users and those close to them. By the late 1990s the City Government had developed legal mechanisms to allow the City to fund needle distribution, and the individuals running the underground exchange serving the Haight arranged for the exchange to become an official service of the abovementioned Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic (HAFMC), with the Clinic receiving grant money from the City to provide needle exchange services. By 2005 the needle exchange service had functionally merged with the Clinic’s youth outreach program, which continued the Clinic’s historic mission of providing homeless youth with support with drug use, legal, education, employment, health, and housing issues. Outreach and case management operated five days a week, and needle exchange operated three evenings a week, with both services being conducted out of the same store-front located on Haight street. In early 2007 the joint youth program/needle exchange separated from HAFMC and became its own non-profit entity called the Homeless Youth Alliance (HYA), which contracted directly with the City to provide case management and needle exchange to street-based youth in the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood. Relationships with HAFMC remained cordial, and HAFMC continued to sublet the store-front premises at the same monthly rate previously budgeted when the program was an internal program.

Planning to relocate a needle exchange and youth service

In mid-2007, disputes between HAFMC and the owners of the building from which HYA provided services led to legal action between the owners and HAFMC. Due to the inherent instability associated with being housed in a building in which the master tenants were in legal conflict with the owners, in a neighbourhood in which commercial rents are far higher than the program could afford, HYA began exploring the possibility of finding a new location. Hamilton United Methodist Church, located approximately 150 m away on Waller Street, parallel to and one block south of Haight Street (see Fig. 1) expressed a willingness to house the program. The space offered by the Church also had additional benefits from a service provision perspective, such as an outside area not directly connected to the street, allowing (for example) service users somewhere to smoke without blocking the sidewalk or alarming commercial neighbours and tourists. In San Francisco, a voter-approved ordinance (the “Citizen’s Right-to-Know Act of 1998” (City and County of San Francisco, 1998) requires that services receiving more than USD$50,000 (€37,500) per year in city funding must notify surrounding residents of any plan to begin or move a program into their neighbourhood. Notification usually takes the form of a posted sign on the proposed new premises, and can also include notification by mail or leaflet. The notification must give details of the program, and give a date and time for a ‘community meeting’ to discuss the proposed move. Any outcome from the meeting has no legal force—all the ordinance requires is that the meeting be held. By August 2007 the negotiations between HYA and the Church were sufficiently advanced that the two organizations decided to call the necessary meeting (known colloquially as a ‘Prop. I’ meeting’, after the ballot Proposition which had authorized the ordinance).

Methods

This paper draws on ethnographic field notes and other textual sources derived from events that took place in the leadup to and following the ‘Prop. I’ meeting mentioned above. The two authors were active participants in these events—the first author (Davidson) was the Chair of the Community Advisory Board of HYA and the second author (Howe) was and is the Executive Director of the program. The first author was at the time a doctoral student at the University of California, San Francisco, and had participated in research and service delivery activities involving needle exchange in Australia and the United States for approximately ten years. The second author had run the needle exchange and later the youth program for several years before HYA was formed, and had herself been homeless in San Francisco for several years during the previous decade.

Data for this paper were drawn from a wide range of sources. These included field notes made by the authors during or immediately following community meetings; at HYA staff meetings; after interactions with community members; after interactions with San Francisco Department of Public Health officials; and after interactions with the media. Additional data included meeting notes and agendas provided by the San Francisco Department of Public Health; email exchanges between community members and HYA; public email mailing lists and blogs created by community members organizing to oppose the move; flyers and other printed materials distributed through the community by HYA and by various ad-hoc community groups; and from media reports.

These data were analysed using a modified version of narrative analysis (Czarniawska, 2004; Riessman, 2008). In brief, this involved an iterative three stage process. In the first stage, we read through our field notes and other gathered texts several times, making preliminary notes as we went. In the second stage, we coded these texts for themes encapsulating issues which were central to the reaction of the community to the proposed relocation of the needle exchange. In the third stage, we wrote memos on our emergent themes in order to elaborate the properties and meanings of these themes, returning repeatedly to the original data sources to further refine these codes and themes.

Housed community response to the proposed relocation

After posting the required signs for the Prop. I meeting, the second author almost immediately began hearing about potential opposition to the move. In particular, a group of housed community residents began attempting to organize their immediate neighbours to attend the Prop. I meeting en-masse, with the intention of presenting a united front opposing the move. This organizing took place largely via public blogs and mailing lists, which also had the presumably unintended effect of galvanizing HYA supporters in the community to attend the meeting as well.

Exacerbating the potential for conflict, and driving some of the initial opposition to HYA, during the months leading up to the Prop. I meeting, a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle (then San Francisco’s daily journal of record), wrote a series of columns on homelessness and on discarded needles in Golden Gate Park, apparently inspired by a story from a fellow-parent about having their infant child tread on a needle in the park (Nevius, 2007a and Personal Communication). In the articles, the columnist characterized HYA in general and the needle exchange in particular as “out of control” and unresponsive to community needs, as well as being the “obvious” source of needles found discarded in adjacent Golden Gate Park (Nevius, 2007a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j). These articles were frequently quoted or reproduced in their entirety in communications sent out by those attempting to organize their neighbours in opposition to the move.

Prop. I meeting

Approximately 250 people attended the Prop. I meeting, held at (and completely filling) the Church, and moderated by employees of the City’s Department of Public Health (as a City-funded health program, the Department’s governing Health Commission had the legal ability to cancel relevant contracts if HYA moved without their approval, normally a rubber-stamp process). Almost all were housed residents of the streets immediately surrounding the church, along with some current and former users of HYA services, some police officers, the Supervisor for the district,2 merchants from the Haight St commercial strip, and representatives of the Church. The meeting opened acrimoniously, with several participants immediately attempting to shout down the attempts of the moderator from the Department of Public Health to explain the format of the meeting with demands for “us” (i.e. housed residents opposed to the proposed move) to be allowed to run the meeting. The first author, as HYA Board Chair, and the pastor from the Church both spoke for about ten minutes each, explaining what we were proposing to do by bringing the program into the Church, with frequent interjections from the crowd. The next two hours were devoted to open-mike statements from 42 people. Approximately a third of those who spoke did so in support of HYA, often to jeers and shouts of “do you live here?”; slightly over half spoke against HYA moving to the Church, usually to cheers and applause; with the remainder making neutral comments or asking essentially neutral questions about the Church or HYA. For most of the meeting the atmosphere remained extremely heated, and included shouted comparisons of housed residents to Nazis, homeless people to dogs, and HYA staff to the mentally ill. However, by the end of the meeting some tension had been relieved by the simple voicing of complaints. On behalf of HYA and the Church, the first author and the pastor told the attendees that we would not to proceed with the move until further meetings could be held to address some of the concerns raised. Another community meeting date was set.

Narrative themes

From the statements of those who spoke against the proposed move a number of themes emerged. Four key themes we will deal with here are ‘a different neighbourhood’, ‘protecting children’, ‘under siege’, and the ‘failures of HYA’. We also describe two themes which emerged from the statements of those who spoke in support of HYA, these being the notion of ‘HYA as a positive force’ and ‘HYA’s links to history’ (note that we excluded from our analysis comments made by HYA employees, board members, or others who had discussed the content of their comments with us prior to the meeting).

The first speaker introduced herself in terms of what block she lived on, and how many years she’d lived there, a format that most of the speakers through the night continued, to the rhetorical detriment of those who spoke in HYA’s defence, as many of the latter were no longer residents of the neighbourhood, having had to move due to the rising cost of housing in the neighbourhood. Many were relatively recent arrivals to the neighbourhood, and often to the city as a whole: “I’m a first-time home owner from New York City”. Almost all represented themselves as home owners rather than renters, in a city where over 60% of housing units are renter-occupied (United States Census Bureau, 2010), nearly twice the US average. And many if not most expressed considerable distress at having bought into an extremely expensive neighbourhood only to find that the same neighbourhood was an internationally famous Mecca for homeless youth.

A different neighbourhood

Many people spoke about the area and what it meant to them, emphasizing the “peaceful and residential character of the neighbourhood”. This clearly startled others present, as the Church is located only one block from the centre of the busy, noisy, and often chaotic Haight commercial strip. Other speakers clarified that they were referring to ‘neighbourhood’ in a micro-sense: the Haight commercial strip was one neighbourhood; the streets they lived on, only a block away, were a different neighbourhood (see Fig. 1 for the approximate location of this micro-neighbourhood).

Slightly more broadly, several asserted that “the neighbourhood has changed”: that the only reason homeless people continued to come to the Haight was because of the social services that had been set up in the 1960s, and that if services were removed from the neighbourhood, the homeless would also leave. Many also complained that there was a disproportionate number of social services in the neighbourhood.3 At a later meeting, one person stated “City Hall has decided the Haight is always going to be funky” and hence would always have to “suffer” from having “inappropriate” social services “dumped” on it. For many of these speakers, the history of the mid-late 1960s appeared to be ancient history with no contemporary relevance, and its invocation by pro-HYA speakers was clearly aggravating.

Protecting children

A second theme, related to the concept that the neighbourhood had changed since the 1960s, was the assertion that there were “a disproportionate number of children and elderly people living in the neighbourhood”.4 Others evoked the presence of a pre-school across the street and other schools in the immediate neighbourhood, or described their “two babies at home who shouldn’t be exposed to this sort of thing.” Almost all of these speakers appeared to consider it self-evident that children and services for homeless youth should not be in close proximity (let alone children and a needle exchange); that merely drawing attention to this proximity would cause the Department of Public Health to block the proposed move. The closest thing to an explicit linking of service provision to a subsequent negative effect on children came from a comment made by the partner of one of the organizers of the ‘anti-’ group,5 who stated “I’m not sure if I’m going to have children, but if I was to have children I’d like to think the neighbourhood they grew up in would be a safe place for them, and having a needle exchange here would be a bad thing for that.”

Under siege

The third major theme, also extending from and overlapping with the narrative of social services attracting people who would not otherwise be in the area, was the idea of being ‘under siege’ by, and having to “deal with”, the consequences of pervasive homelessness: public defecation; public intoxication and fighting; discarded needles in gardens; theft; defecation; being threatened or verbally abused by homeless youth; garbage; urine on sidewalks; defecation; homeless people sleeping in doorways; and violent dogs kept by the homeless. And defecation.6 These complaints, while easily summarized due to their repetitive nature, consumed at least half the speaking time of those opposing HYA’s move. Notably, in these complaints the housed residents were joined by a small number of speakers who identified themselves as business owners operating on Haight Street itself, who also complained of “the mess” they needed to clean up each morning before opening their businesses, and their fears that homeless, mentally ill, and/or intoxicated people were driving away business.

The failures of HYA

Finally, also relating to complaints about the role of social services in ‘attracting’ people to the Haight, were complaints or negative comments about HYA itself. Interestingly, and in sharp contrast to our expectations, those who specifically addressed HYA’s mission usually did so in terms which gave lip-service to the basic concept: “We know needle exchange is needed to control AIDS, but…”, or “I’m not opposed to needle exchange, but…”, with the ‘but’ being often quite literally “but I don’t want it right next to me.” One speaker caused an unintentional moment of levity by stating without apparent irony “I’m not a NIMBY, but I really don’t want this service right in my backyard.” Instead of opposing needle exchange on principle, speakers instead tended to repeat the accusations raised in the San Francisco Chronicle that HYA was “out of control”. Few specified exactly what this meant to them, with the exception of those who complained that HYA was breaching the “rules” of needle exchange because it gave out needles to people who didn’t bring any in, rather than insist on a strict one-for-one exchange.7 Others expressed support for the concept of services ten for homeless youth, but then asked if there was any evidence that the specific services that HYA offered had any measurable impact on homelessness, and rhetorically asked the Department of Public Health representatives present to provide “proof” that HYA was fulfilling contractual obligations.

HYA as a positive force

Speakers who spoke in support of HYA and the proposed move were for the most part more reactive than those who spoke against, in that many of their comments were clearly in response to statements made by earlier anti-HYA speakers. This was particularly noticeable with respect to the idea that HYA was ‘out of control’ or ineffective at addressing the problems faced by its end-users—many supporters spoke of the professionalism of HYA and its staff, and emphasized that the neighbourhood would be more chaotic rather than less if HYA was not present to provide services to youth on the street. One speaker caused uproar by suggesting that at least some of those present might be glad of HYA one day, since statistically at least some of their children would experience diffi-culties with drug use later in life. Another individual in a suit and tie introduced himself as a local businessman, but then surprised many by going on to say he’d been homeless a decade earlier and the only reason he was still alive, let alone a productive tax-paying member of society, was that he’d received support and services from HYA.

HYA’s links to history

Like those who spoke against HYA, supporters also often made reference to the character of the neighbourhood. Unlike those opposed to the move, however, HYA supporters made frequent reference to the role of (post-1950s) history in shaping the meaning of the neighbourhood—for example, some speakers drew attention to the Haight as the birthplace of the Free Medical Clinic movement (a grass roots response to the lack of affordable healthcare in the United States which began with the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic in the late 1960s (Weiss, 2005, p. 24ff)), and pointed out that HYA and its organizational predecessors had been delivering services to homeless youth in the Haight continuously since 1967. More broadly, HYA supporters talked about the neighbourhood’s historic role as a “refuge” for outcasts; as a place where people had been coming “for a long time” to find community not available to them elsewhere; and, fundamentally, that homeless youth who lived in the neighbourhood were also ‘legitimate’ residents who had as much right to be there as those who could afford to buy multi-million dollar homes.

Aftermath

Two other community meetings were held over the next month, with rapidly decreasing attendance (only one resident attended the final meeting, gamely expressing his opposition to the move to the dozen or so DPH officials and needle exchange representatives politely arrayed in a circle around him). While the remaining meetings were being held, the Church requested HYA postpone further planning for a move. However, HYA’s concerns about the stability of the lease at the existing premises were resolved after discussions with both the master lease holder and the owners, who both expressed distress at the treatment HYA had received at the Prop. I meeting and committed to ensuring the stability of HYA’s premises. In addition it also became clear that internal fiscal and political conditions at the Church made the proposed move a poor choice for long term stability, so the project to move service delivery to the church was abandoned. In the months after the Prop. I meeting, HYA received several thousand dollars in donations from housed residents in the neighbourhood who, in the letters and cards accompanying their cheques, expressed high levels of distress at the reception HYA had received at the Prop. I meeting and assurances that “the entire neighbourhood doesn’t feel the way those people do.” In addition, a group of housed residents shortly afterwards volunteered to cook a communal meal for Christmas for the young people who use HYA services, an act which has since become an annual tradition.

In the longer run, the process of organizing to oppose HYA’s move to the Church also appears to have led some of those involved to become engaged in other efforts to reduce the presence of homelessness and organizations serving them from the neighbourhood. For example, a recycling centre located on the edge of Golden Gate Park adjoining the Haight was closed in late 2012 after nearly 40 years of operation in part due to pressure from housed residents, who complained about the noise of “homeless people pushing shopping trolleys full of cans down the street at 3am” and that that the centre “attracted the homeless” (since recycling scrap metal is one of the few legal income generating methods available to the homeless in San Francisco) (Koskey, 2012). The same residents were also actively involved in supporting a controversial City ordinance passed in 2010 banning “sitting or lying” on sidewalks, an ordinance which police records show has been disproportionately enforced in the Haight (Knight, 2013).

Interpretation

In 2009, the novelist Jonathan Franzen, in a fiction piece in the New Yorker,8 described life for middle-class families moving into a run-down, but slowly gentrifying neighbourhood:

In the earliest years… the collective task in Ramsey Hill was to relearn certain life skills that your own parents had fled to the suburbs specifically to unlearn, like how to interest the local cops in actually doing their job, and how to protect a bike from a highly motivated thief, and when to bother rousting a drunk from your lawn furniture, and how to encourage feral cats to shit in somebody else’s children’s sandbox, and how to determine whether a public school sucked too much to bother trying to fix it (Franzen, 2009, June, p. 79).

Unlike Franzen’s fictional yuppie families, who were aware they were moving into a run-down neighbourhood, for at least some of those who attended the Prop. I meeting, at least part of their outrage seemed to be that they believed they were moving into a well-to-do neighbourhood, one they had paid large sums to buy into, only to find that they had moved into two neighbourhoods. One the well-to-do, walkable neighbourhood with good schools, nice shops, and a stunning park that they had sacrificed so much to join; the other a chaotic floating community of homelessness and social service agencies who, unlike those in many other communities in America, actively asserted their right to be present based in part on the unique history of the neighbourhood.

Contested spaces

Following Massey (1995) and (Low and Lawrence-Zúniga, 2003, p. 18ff), we therefore suggest that the Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood might fruitfully be seen as a kind of ‘contested space’ in that there are multiple narratives being presented about what the neighbourhood ‘is’, and that these narratives (or ‘meanings’ in Massey’s usage) are being “mobilized in battles over the material future of places.” (Massey, 1995, p. 2)

A wide range of authors have written about the notion of contested space, in particular through the lenses of power and class (for example see Harvey (1985, 1993), Castells (1983), Davis (1990) and Wright (1997)). These approaches have in common that they tend to centre on contestation over physical resources—in this case on the control of physical space. Extending from these approaches, Lefebvre [1974] (1992) argues that control over physical space is usually so central because such control also confers control over the social relations produced by the space in question. In this light, what is at play in Massey’s ‘contested meanings’ is not just the ‘material future’ of physical space but the set of sociospatial relations which will even be possible in that space in the future. We see these contestations over the ‘meaning’ of the Haight appear repeatedly during comments made by both pro- and anti-HYA speakers at the Prop. I meeting. Examples include claims that the neighbourhood is “peaceful and residential” or, alternately, that the neighbourhood has “always” been a refuge for outcasts.

Also central to claims about the meanings of a space is the ability of people to locate themselves as “rightful producers” of that space (a term coined by the anthropologist Margaret (Rodman, 1992, p. 644)9); as people whose voices should have particular weight due to some aspect of their relationship to the space. Again, as noted above, many speakers at the Prop. I meeting explicitly introduced themselves in terms clearly intended to locate them as rightful producers, and to imply that others were not: for example, by introducing themselves as homeowners or long-term residents, or by shouting “do you live here?” at those making pro-HYA statements. In a similar if less direct fashion, statements by pro-HYA speakers invoking the ‘unbroken lineage’ between HYA and the social movements of the 1960s could also be seen as attempting to locate HYA and those who spoke for it as inheritors and participants in that ongoing rightful production of meaning for the neighbourhood.

Needless to say, these differing narratives about the history and ‘meaning’ of the Haight do considerable work in shaping how homeless people generally and users of HYA services in particular are seen. In the historically-rooted narratives presented by pro-HYA speakers, the neighbourhood becomes a place of refuge in which these groups are ‘legitimately present’, as are organisations who provide them with services. In the narratives presented by those opposed to HYA, the neighbourhood becomes a place for the upper-middle class to reside alongside a geographically-constrained tourism, and the homeless become, at best, distracting nuisances, and, at worst, outright impediments to a reasonable enjoyment of one’s neighbourhood.

Defensive place-making

We suggest that in the months and years prior to the events described above, the arriviste residents of the streets to the south of the Haight commercial strip had discovered that there were multiple voices in the neighbourhood which had clear claims to be “rightful producers” of the meanings of the space. More importantly, both the diversity of claims and the meanings being produced by these claimants were at least partially acknowledged by City Hall (recall the complaint that “City Hall has decided the Haight is always going to be funky”). Worse still, this meant the enforcement arms of local government—from the police through to Commissions and Departments with the authority to accept or deny plans to locate social service agencies—were also ‘failing’ to see the Haight solely as an upper-middle class residential area, and were responding to the demands of home-owning and housed residents as just one of a number of legitimate voices.

As a consequence, in the tone and words of at least some of those who opposed HYA’s proposed move, both at the Prop. I meeting and as covered by Nevius in the San Francisco Chronicle, we see (as Shaw (2006) saw in her work on needle exchange in Massachusetts) a kind of ‘victimhood’ being expressed. Complaints of being “under siege” by the homeless; of police failure to respond to complaints about the presence of homeless; and that “City Hall has decided the Haight is always going to be funky” all come across as expressions of perceived loss of control over one’s environment due to the acts of external forces.

Our data suggests that in response to this sense of loss of control, at least some residents of the streets to the south of Haight Street had gone beyond the responses to ‘undesirable neighbours’ described in the NIMBY literature, and were engaged in what we have come to call ‘defensive place-making’. By this, we mean efforts to carve out a ‘separate’ neighbourhood or enclave from within a larger area, and by doing so limit who can speak for the new space and hence what the material future of the space will be—what services and/or people are ‘appropriate’ for the ‘new’ space. By ‘defensive’, we mean as a response to a situation where those engaged feel the responses normally available to them have failed—in this case, the exercise of social capital to induce the state and its agencies to exclude, remove, or at least repress and control, a less-well resourced group of citizens.

In some respects this concept reflects aspects of the broader scholarship on American responses to perceived social disorder—the ‘gated community’, for example, is also ‘defensive’ in the sense used above, and is also about responding to perceptions of social disorder by creating a space in which a deliberately limited set of people are able to define who and what ‘belongs’ (Low, 2003). However in our usage, we are primarily interested in rhetorical place making in already extant communities, rather than the planned and literally gated places of gated communities.

In our data, defensive place making involved two components: engaging in boundary making, and engaging in efforts to more ‘strongly classify’ the space. With respect to the first of these, the geographer Doreen Massey (1995) sees boundaries primarily as a social construct which “are one means of organizing social space. They are, or may be, part of the process of place-making” (Massey, 1995, p. 68, original emphasis). In many of the narratives of those opposed to HYA’s proposed move, we see an articulation of a ‘place’ which is different from ‘that place over there’: for example, the insistence that despite being a single block from the busy Haight Street commercial strip, that the neighbourhood was “quiet and peaceful”; or despite the US Census data showing just over 90% of the Haight’s population to be aged between 18 and 64, that the neighbourhood was “full of small children and the elderly”. As noted above, many of the anti-HYA speakers introduced themselves in terms of what street and block they lived on (for example “I live on the sixteen hundred block of Waller”). In combination, we suggest these speakers are engaged in a kind of boundary making, not so much in the sense of formally drawing lines on a map but in the sense of defining the characteristics which make ‘this place’ different from ‘that place over there’, as well as identifying specific locations that are part of ‘this place’ and hence, collectively, identifying at least roughly where ‘this place’ might be said to be (see Fig. 1 for the approximate bounds of the area defined in this way by speakers at the Prop. I meeting).

Secondly, Massey takes up (Sibley, 1992, p. 115) on the notion of “strongly and weakly classified spaces”:

Generally, strongly classified spaces will also be strongly framed, in that there is a concern with separation and order, as there is, for example, in many middle-class suburbs. Weak framing would suggest more numerous and more fluid relationships between people and the built environment that occur with strong framing… Using this schema, it is possible to see how space contributes to the social construction of the outsider…I would argue, therefore, that there is a connection between strong classification of space and the rejection of social groups who are non-conforming (Massey, 1995, p. 74).

In their complaints about the activities of the homeless, such as defecation, sleeping, fighting, and drinking, housed residents are in essence complaining about the fact that, in Massey and Sibley’s language, the neighbourhood is awash with the “numerous and … fluid relationships between people and the built environment” which characterize a weakly classified space. In their complaints about the ‘undesirable’ activities of the homeless, these housed residents are also articulating their desire for an environment where the ‘appropriate activities’ for the place are far more tightly constrained; where activities which housed residents would themselves conduct in private spaces (such as defecation, drinking, and fighting) could not or would not happen in public spaces.

In this light, the contestation over space and service provision in neighbourhoods such as the Haight becomes one of residents wanting to create (or re-create, if one looks at it from the perspective of pre-1930s history) a ‘strongly classified space’ where the range of activities which are able to take place in public are more tightly constrained. In order to establish such a space however, the residents of the blocks to the south of Haight Street first needed to carve out a ‘new’ neighbourhood, one where those who had pre-extant narratives (and the not-inconsiderable weight of history) about the Haight as a refuge for the weird, the wonderful, and the outcast, could simply be excluded as ‘outsiders’ with no legitimate voice in the newly defined community (“do you live here?”).

Given this process of boundary making and reclassification, it is unsurprising that the news that a needle exchange and service for homeless youth was planning to move almost to the geographic centre of this newly emerging area caused such visceral reaction. The proposed move challenged the boundary making, by bringing an organization with strong ties to the narrative of the Haight as a place for all to the centre of a space being set up to exclude that same narrative. The proposed move also challenged attempts to redefine the area as a strongly classified space, as HYA’s arrival would bring with it both a population (homeless youth) and a range of activities (handing out needles for drug use; allowing young people to stand on the pavement outside the service smoking cigarettes) which would broaden the ‘acceptable’ range of activities and remake or reinforce the area as a weakly classified space notable for its fluidity and transience.

Conclusion

Many if not most of the specific issues raised in the Prop. I meeting are familiar from the existing literature on NIMBYism and services for people who use drugs. As just one example, Smith (2010), describing opposition to a methadone clinic in Toronto, Canada, documents similar concerns being expressed about services being ‘dumped’ in neighbourhoods (p. 862), the physical disorder of garbage, vomiting, and defecation (pp. 863–864), the intimidating nature of service users (p. 864), and attacks on the validity of the methods being used by the service (p. 863).

One of the key findings to emerge from the work described above however is the idea that the social history of a place shapes notions of neighbourhood, and these in turn impact the ways in which the ‘social disorder’ represented by homeless youth are understood and responded to. The Haight has for nearly half a century been a place for people to go for a kind of sanctuary, and clearly has many residents who still think of themselves as recipients of, and participants in that legacy. This means that despite skyrocketing housing prices, and despite the opposition of arriviste home owners with little notion of the ongoing history of their own neighbourhood, there is still a sufficient sense that homeless people, and people who use drugs, and the agencies that provide them services, are ‘legitimately present’ in the neighbourhood, enough so that their presence is defended by both City government and a sizeable portion of the housed community.

The response of at least some housed residents was to therefore engage in what we have termed ‘defensive place making’, rhetorically carving themselves out from the larger neighbourhood in an effort to create a new, strongly classified, space where they could ignore pre-existing narratives of inclusion and history and more effectively justify their desire to exclude their fellow citizens. HYA’s proposed move threatened to completely erase this effort, by symbolically locating an agency directly connected to the history of the broader neighbourhood right in the middle of this new, fragile space. In hindsight, it is unsurprising that even though the housed residents of the area were, by American standards, politically progressive and accepting of the concept of needle exchange and other services for the homeless, they reacted immediately and vocally.

We suggest that our experiences have two main implications for those interested in processes of locating controversial services. Firstly, reflecting the prior scholarship of others, our experience suggests that narratives about an area which speak to an inclusionary history; which emphasize that otherwise controversial groups or services ‘belong’ in an area, are a particularly potent tool for responding to attempts to exclude both people and services. Secondly, and perhaps more originally, we found that in a situation where such narratives were effectively deployed, that one possible outcome was for some residents to be left feeling ‘under siege’ or ‘victims’ of the situation, and to engage in what we defined as ‘defensive place making’ in which they attempt to remake the neighbourhood into multiple neighbourhoods. Such ‘new neighbourhoods’ are likely to be particularly virulently ‘defended’ against perceived encroachment. When engaged in attempting to locate or relocate services in a neighbourhood, our experience suggests that finding out if such ‘new neighbourhoods’ exist in the minds of one’s neighbours or neighbours-to-be, and if so avoiding them where possible, may reduce the level of opposition.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rachel Washburn for providing valuable feedback on drafts of this paper. Dr. Davidson’s effort during data collection was funded by the California HIV/AIDS Research Program, grant # D06-SF-424, and during manuscript production by the U.S. National Institute for Drug Abuse, grant # K01DA032443.

Footnotes

The oldest neighbourhood organization still extant, the Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Association (HANC), began as a freeway opposition group in the 1950s.

The Board of Supervisors is the governing entity in San Francisco, population approximately 850,000, and is headed by a mayor; supervisors are elected by geographic district; the mayor is elected in a city-wide election. The city government in San Francisco has an annual budget of approximately USD$6 Billion (€4.5 Billion) and controls police and public health, among other key public services.

As well as HYA and the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, the neighbourhood was at the time home to a soup kitchen, another agency providing case management and drop-in services to youth, a youth homeless shelter, and a residential drug treatment service.

U.S. Census block data for 2000 shows that, in fact, the HYA site had the second lowest number of children under 18 and elderly over 65 years old within 100 m of any of the fifteen needle exchange sites then operating in San Francisco, and that over 90% of those residing in the streets to the immediate South of Haight Street were aged between 18 and 65 (United States Census Bureau, 2010).

A computer programmer recently moved from the state of Georgia, who, as of 2012, had already moved on to another city.

In a post-meeting debrief, junior HYA staff expressed anger and laughing disbelief about the “obsession” with defecation, since many of those who spoke about the problems of defecation had also spent the past several years in virulent opposition to the City’s proposal to install a single public toilet in the neighbourhood (Fishman, 2006).

While strict one-for-one exchange had been a common policy in the early 1990s when needle exchanges were first legalized in the United States, by 2007 San Francisco Department of Public Health policy actively required exchanges in San Francisco to provide up to ten needles to any person who has less than ten needles, including to those with no needles at all (San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health & Prevention HIV Section, 2011, p. 11).

Later incorporated into his 2010 novel, Freedom.

Although Rodman’s intent in coining the term was largely to encourage researchers to improve their analysis of space by attending to the multiplicity of local voices found in places rather than their own preconceived notions.

Conflict of interest statement

This paper describes events relating to the Homeless Youth Alliance (HYA). During the events described, Dr. Davidson was unpaid chair of HYA’s community advisory board, and Ms. Howe was the paid executive director of HYA. Other than this association, the authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship with people or organisations that could inappropriately influence this work.

References

- Beitel KE. Davis Ph D Dissertation. University of California: 2004. Transforming San Francisco: Community, capital, and the local state in the era of globalization, 1956–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brechin GA. Imperial San Francisco: Urban power, earthly ruin. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castells M. The city and the grassroots. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- City and County of San Francisco. San Francisco Municipal Code, Part I (Administrative Code) 1998;Chapter 79 [Google Scholar]

- Colón I, Marston B. Resistance to a residential AIDS home: An empirical test of NIMBY? Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37(3):135–145. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska B. Narratives in social science research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. City of quartz: Excavating the future in Los Angeles. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dear M. Understanding and overcoming the NIMBY syndrome? Journal of the American Planning Association. 1992;58(3):288–300. [Google Scholar]

- Dear M, Gleeson B. Community attitudes toward the homeless? Urban Geography. 1991;12(2):155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman K. Haight street toilet: Residents, chief of police, Heather Fong & Director of DPW, Dr Fred Abadi weigh in…. Haight Asbury Improvement Association Newsletter. 2006 Fall;:6. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald JL. Supervised injecting facilities: A case study of contrasting narratives in a contested health policy arena? Critical Public Health. 2013;23(1):77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen J. Good neighbors. The New Yorker. 2009 Jun;:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. Studies in the history and theory of capitalist urbanization, consciousness and the urban experience. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. From space to place and back again: Reflections on the condition of postmodernity. In: Bird J, Curtis B, Putnam T, Robertson G, Tickner L, editors. Mapping the futures: Local cultures, global change. London: Routledge; 1993. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Knight H. Sit/lie law primarily enforced in Haight. San Francisco Chronicle 2013 Sep 20; [Google Scholar]

- Koskey A. State high court denies recycling center’s request to review eviction. San Francisco Examiner 2012 Sep 17; [Google Scholar]

- Law RM, Takahashi LM. HIV, AIDS and human services: Exploring public attitudes in West Hollywood, California. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2000;8(2):90–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre H. The production of space. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 1992. Plan of the present work; pp. 1–67. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Low S. Behind the gates: Life, security, and the pursuit of happiness in fortress America. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Low SM, Lawrence-Zúniga D. Locating culture. In: Low SM, Lawrence-Zúniga D, editors. The anthropology of space and place: Locating culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon-Callo V. Making sense of NIMBY: Poverty, power and community opposition to homeless shelters. City & Society. 2001;13(2):183–209. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M, Law M, Kaldor J, Hales J, Dore JG. Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes for preventing HIV transmission? International Journal of Drug Policy. 2003;14(5–6):353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. A Place in the world? Places, cultures and globalization. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. The conceptualization of place; pp. 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Golden Gate Park sweep—Can city make it stick?: ‘March of junkies’: Haight’s residents fume over needles. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007a Aug 2; A1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. The face of SF. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007b Aug 5; A2. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Poster child for what is wrong with park: How is it a public nuisance manages to hold off the S. F. justice system? San Francisco Chronicle. 2007c Aug 7; D1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Home runs – not homelessness – reflect city’s spirit. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007d Aug 9; A1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Golden Gate Park mess – a one-month checkup. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007e Aug 21; A1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Look around and learn. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007f Aug 22; B1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Picking up needles isn’t a real fix. San Francisco Chronicle 2007g Aug 23; [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Cash machine for the homeless. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007h Aug 26; B1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. Both sides get say on camping in the park. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007i Aug 28; B1. [Google Scholar]

- Nevius CW. The situation at Golden Gate Park: Needles cleared, campers on move. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007j Sep 23; B1. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KF. Residential rehabilitation financing: The elements of a city-wide strateg. Urban Law Annual. 1978;15:53–101. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rodman MC. Empowering place: Multilocality and multivocality? American Anthropologist. 1992;94(3):640–656. [Google Scholar]

- San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health and Prevention HIV Section. Syringe access and disposal program policies and guidelines. San Francisco: San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health and Prevention HIV Section; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SJ. Public citizens, marginalized communities: The struggle for syringe exchange in Springfield, Massachusetts. Medical Anthropology. 2006;25(1):31–63. doi: 10.1080/01459740500488510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley D. Outsiders in society and space. In: Anderson K, Gale F, editors. Inventing places: Studies in cultural geography. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire; 1992. pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CBR. Socio-spatial stigmatization and the contested space of addiction treatment: Remapping strategies of opposition to the disorder of drugs? Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70(6):859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Luce J. Love needs care: A history of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic and its pioneer role in treating drug-abuse problems. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Staller KM. Runaways: How the sixties counterculture shaped today’s practices and policies. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strike CJ, Myers T, Millson M. Finding a place for needle exchange programs? Critical Public Health. 2004;14(3):261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. The socio-spatial stigmatization of homelessness and HIV/AIDS: Toward an explanation of the NIMBY syndrome? Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45(6):903–914. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00432-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. Homelessness, AIDS, and stigmatization: The NIMBY Syndrome in the United States at the End of the Twentieth Century. London: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM, Dear MJ. The changing dynamics of community opposition to human service facilities? Journal of the American Planning Association. 1997;63(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B. Placing the dynamics of syringe exchange programs in the United States? Health and Place. 2007;13(2):417–431. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. DP-1: Profile of general population and housing characteristics: 2010 demographic profile data 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss GL. Grassroots medicine: The story of America’s free health clinics. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilton RD. The constitution of difference: Space and psyche in landscapes of exclusion? Geoforum. 1998;29(2):173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: A comprehensive review of the international evidence? Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(6–7):777–813. doi: 10.1080/10826080600669579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright T. Out of place: Homeless mobilizations, subcities, and contested landscapes. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]