Abstract

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and non-recombining Y chromosome (NRY) are inherited uni-parentally from mother to daughter or from father to son respectively. Their polymorphism has initially been studied throughout populations of the world to demonstrate the “Out of Africa” hypothesis. Here, to correlate the distribution of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) in different populations of insular Asia, we analyze the mtDNA information (lineages) obtained from genotyping of the hyper variable region (HVS I & II) among 1400 individuals from island Southeast Asia (ISEA), Taiwan and Fujian and supplemented with the analysis of relevant coding region polymorphisms. Lineages that best represented a clade (a branch of the genetic tree) in the phylogeny were further analyzed using complete genomic mtDNA sequencing. Finally, these complete mtDNA sequences were used to construct a most parsimonious tree which now constitutes the most up-to-date mtDNA dataset available on ISEA and Taiwan. This analysis has exposed new insights of the evolutionary history of insular Asia and has strong implications in assessing possible correlations with linguistic, archaeology, demography and the NPC distribution in populations within these regions. To obtain a more objective and balanced genetic point of view, slowly evolving biallelic Y single nucleotide polymorphism (Y-SNP) was also analyzed. As in the first step above, the technique was first applied to determine affinities (macro analysis) between populations of insular Asia. Secondly, sixteen Y short tandem repeats (Y-STR) were used as they allow deeper insight (micro analysis) into the relationship between individuals of a same region. Together, mtDNA and NRY allowed a better definition of the relational, demographic, cultural and genetic components that constitute the make up of the present day peoples of ISEA. Outstanding findings were obtained on the routes of migration that occurred along with the spread of NPC during the settlement of insular Asia. The results of this analysis will be discussed using a conceptual approach.

Keywords: Mitochondrial DNA, Polynesian motif, Out of Taiwan, Austronesian speakers

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), often referenced as the “Cantonese Cancer”, could also be referenced as the “Bai Yue Cancer” as NPC is most prominent among these people. Descendant of the Bai Yue have become a great migrating people and survey of their distribution across the world today mimic surprisingly the distribution of NPC in different populations[1]. NPC has been observed among Taiwanese Han and Taiwan aborigines (TwA), among island Southeast Asia (ISEA) islanders and Polynesians. Except for the Han who moved to Taiwan 400 years before present (YBP) and finally contributed to 98% of the Taiwan population[2], TwA and most other populations of ISEA are speakers of Austronesian languages and are believed to share a common ancestry with the Bai Yue of south China[3]. It has been genetically demonstrated [4]–[7] that islanders from ISEA and TwA had separated from mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA) more than 15 000 YBP.

All extant Asian or Melanesian individual mtDNA types are descendent of founding macro haplogroup either type M or type N[8],[9]. These two mtDNA haplogroups share a common ancestry with African super haplogroup L3 which was carried by the only small group of people who successfully passed through the horn of Africa ∼80 000 YBP and later migrated “out of Africa” ∼60 000 YBP as a group[9] bearing only haplogroups M and N (the two daughters of haplogroup L3). In less than 5 000 years (a time that was too short to allow for the appearance or the fixation of new mutations of mtDNA macro haplogroups N or M), these peoples established settlements in India, Sundaland (MSEA), Papua New Guinea[10] and Australia[11]. Much later, in the last 15 000 years when circumstances, dictated by fluctuations in sea levels and climatic conditions, were more favourable, they settled in America. Interestingly, European ancestors from west Eurasia (a small group of people all belonging to mtDNA haplogroup N) moved to Europe much later than the eastern wave (∼35 000 YBP) and intrinsically the genetic diversity observed in Europeans is less than the genetic diversity seen in Asians which itself is less than the diversity of Africans.

In this report we present phylogenies of a few pertinent mtDNA haplogroups which bring new insights toward a better understanding of various population migration and settlement events that occurred among non-NPC-affected populations from Melanesia [Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Australian aborigines], and NPC-affected populations from MSEA and ISEA (and Polynesia).

The Melanesians

In 2005 and 2007, Friedlander et al.[12] and Hudjashov et al.[11] produced trees of complete mtDNA sequences of founding macro haplogroups M and N showing that aboriginal Australians were most closely related to the autochthonous populations of New Guinea/Melanesia, indicating that prehistoric Australia and New Guinea were occupied initially as a unique Palaeolithic colonization event ∼50 000 YBP. The question remains as to whether PNG and Australia were reached separately, sequentially, or even several times after the initial settlement event. For this they separately analyzed the distribution of all subtypes of Melanesian mtDNA haplogroups M and N. Only one mtDNA subtype of macro haplogroup N (haplogroup P) will be described here [5],[11]–[13].

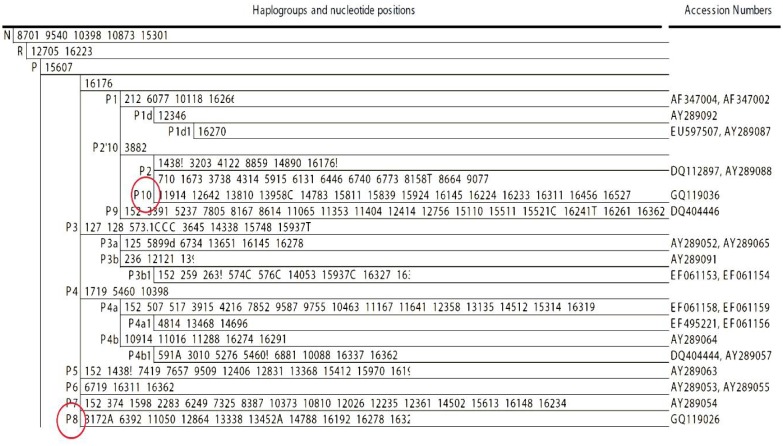

While some variants of P (P1 and P2 in Figure 1) [5],[14]–[16] were very common in Papua New Guinea [10], variants P5, P6, P7 and P9 were unique to Australia. Only more recent subtypes of variants P3 and P4 were seen in PNG and Australia[17].

Figure 1. Most Parsimonious tree of haplogroup P (a subtype of N and R). Before 2009, all known branches of P were seen either in Australia or in Melanesia. Here new branches, namely P8 and P10 (circled in left column), were found in the Philippines[5],[14]–[16]. Sequence accession number were obtained from Phylotee[16].

Molecular dating of haplogroup P in Melanesia and Australia suggested that a first stage expansion had occurred before people reached Sahul (∼50 000 YBP), when ancestral haplogroup P first appeared with mutation at nucleotide position (np) 15607 (Figure 1) from its mtDNA ancestral macro haplogroup N coming directly from the Middle East. It is therefore during this early period, when haplogroup P was still undifferentiated, that anatomically modern Human moved to PNG and Australia where haplogroup subtypes P1 and P2 in PNG and P5, P6, P7 and P9 in Australia would later appear. This view was supported in 2007 by Hudjashov et al.[11] who indicated that groups of modern humans who immigrated to Australia or PNG had been isolated since their initial settlement, and that haplogroup P had probably made it first appearance in the close vicinity of PNG longitudes[11],[12]. Hudjashov et al.[11], observing the sharing of P3 and P4 between the two regions, hypothesized gene flow of subtypes of P3 and P4 between PNG and Australia. Alternatively, subtypes of haplogroups P3 and P4 dating 30 000 YBP could have independently moved in late Pleistocene from ISEA where they initially expanded and disappeared by drift as populations were small. The most parsimonious tree in Figure 1 shows that only distinct subtypes of P3 or P4 are seen in either Australia (P3a and P4b1) or PNG (P3b and P4a/b), indicating independent dispersals from ISEA but no later sharing due to migrations from or to PNG or Australia.

This last alternative suggesting an origin of P in ISEA was supported in 2009 when Trejaut et al.[18] sequenced two new haplogroup P (P8 and P10) from Philippine individuals[5]. As with all other major branches of haplogroup P, P8 derived from founder macro haplogroup N by a single coding region mutation at np 15607 (left circle in Figure 1) and expanded locally. Since no other haplogroup P were found in ISEA (except for P10, see below), one could suppose: (1) That people from PNG (rather than from Australia) migrated back and reached the Philippines, but so far, no trace of P8 has yet been found outside of the Philippines! (2) That P8 is the result of a recurrent mutation at np 15607. This alternative is unlikely, as np 15607 is not known as a hot spot; and (3) That when np 15607 first appeared in western ISEA, macro haplogroup P first expanded there and then dispersed randomly reaching the Philippines, PNG and Australia separately. Interestingly, all traces of P in populations situated between PNG and the Philippines would have either disappeared by drift or not yet been sampled.

As mentioned above, the other P matrilineage (P10) is only seen in Philippines[15],[19],[20]. In addition to np 15607, its subtypes share a transition at np 3882 with haplogroup P2, a haplogroup found only in New Guinea and Near Oceania. It is unlikely that P10 is the result of a recent back migration from New Guinea to the Philippines, as P10, like P8, is completely absent in other regions of ISEA. Rather, the hypothesis proposed above in “c” is most likely.

In search for supplementary supporting arguments to this hypothesis, our laboratory collected 400 specimens from Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Java and a few from east Indonesia. As foreseen by Hill et al.[19], we found that as much as 14% of the mtDNA diversity seen in ISEA populations was made up of new non-interconnecting deep-rooted lineages (basal haplogroups descendent of macro haplogroups M), indicating long-term in situ evolution (isolation). These archaic matrilineages, similarly to haplogroup P, were connected directly in a star-like fashion to founding macro haplogroups M (as haplogroup P is connected to N). Similar observations have been described in the SEA mtDNA structures of the Andamanese (M31 and M32)[21],[22] in Malaysia (M21 and 22)[23], in Papua New Guinea (M27, M28 and M29)[14], in India [24], and more recently in the Philippines (M71 to M73)[5],[15]. Further, complete sequencing of all deep-rooted lineages described in the studies of Trejaut et al.[18],[25] characterized more than 23 and 6 new basal haplogroups belonging to branches not yet defined of macro haplogroups M and N respectively. Molecular dating estimates of these basal groups, obtained from coding region variations (46 000 YBP to 50 000 YBP), suggested that these lineages represented vestiges of a Pleistocene genetic pool of the first anatomically modern humans who settled the ancient continent of Sundaland most likely much before the appearance of NPC.

In summary, the unexpected high number of new basal lineages in ISEA, rooting directly to superhaplogroups M or N, and the presence of similarly unique and unshared basal lineages all along the southern hemisphere coastlines, from the horn of Africa through Melanesia and then to New Guinea, Near Oceania or Australia, may have implications for the effective population size of the first settlers, and imply a rapid eastward migration (∼700 meters per year)[23]. Like haplogroup P, novel haplogroups found in ISEA, did not share any structural characteristics with any other M and N subgroups previously described for East Asia, West Asia, India or Eurasia. Most remarkably, they indicated that west ISEA had been a very active center of expansion and of dispersal in the late Paleolithic period. Their low frequency (14%) in Indonesia strongly suggests that the initial ISEA gene pool has been replaced as the result of an early Holocene wave of migration from MSEA[26] by demic diffusion (total replacement of the first Paleolithic settlers of ISEA). This universally accepted view should be reassessed, as we have shown here that population replacement by migrants from MSEA was incomplete (14% of non Asian matrilineages). The remaining 86% sequences in ISEA and Taiwan found their ancestry in SEA, they are shared by most groups of Austronesian speakers and are characterized by haplotypes that belonged to already well defined and much younger twigs of haplogroup M, such as G1, D4, M9, M7, M13 and Z, or of haplogroup N such as B4, B5, F1 and N9a. Most importantly they represent non-Melanesian populations, most likely bearers of NPC, and correspond to much more recent migrations from MSEA.

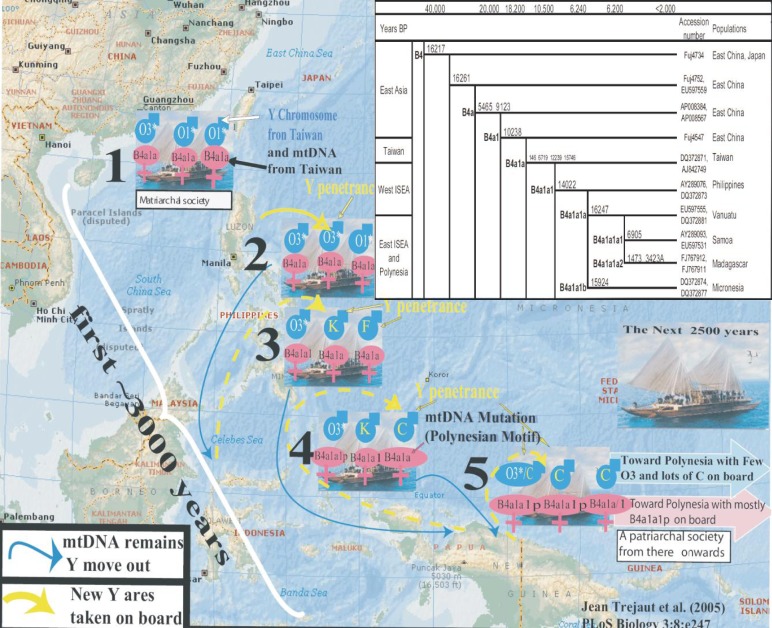

“Express train”, “Slow boat” and “Out of Taiwan” Models Are All Components of a Single Phenomenon

Previous mtDNA variation studies in populations of the Pacific and western Indonesia have shown that a particular mtDNA mutation consisting of a deletion of nine base pairs (9bp-del), between the cytochrome oxidase II and lysyl-tRNA genes, has reached gene fixation in most Austronesian-speaking populations of the Pacific islands[27]–[30] and Madagascar[31]. It was suggested that the 9bp-del was spread by bearers of mtDNA haplogroup B in MSEA where incidence of NPC is high. It was later determined that an mtDNA substitution at np 16217 arose on the background of the 9-bp deletion, and was followed by a substitution at np 16261 which is seen throughout mainland and insular Asia among all bearers of haplogroup B4a1 (insert in Figure 2) [32]. In the pre-Holocene period, three other substitutions (at nps 6719, 12239 and 15746) appeared on a branch of B4a1 and now determine haplogroup B4a1a. B4a1a dispersed so quickly throughout western ISEA and Taiwan where the type is the most prominent that it is difficult to determine the location of its origin[7]. At the beginning of the Neolithic period another mutation on one of the daughters of haplogroup B4a1a appeared (at np 14022) which now determines haplogroup B4a1a1 (also described as the proto-Polynesian motif). B4a1a1 was described and sequenced separately[5],[7],[14] and although its highest frequency and diversity is seen in East Coast PNG and Near Oceania, it is still believed to have first appeared in western ISEA (a region comprising Borneo, the Philippines and Sulawesi) ∼6 000 YBP in a time frame predating the “Polynesian Diaspora”. The appearance of np 14022 was soon followed by the appearance of another transition at np 16247[29],[33],[34]. It was proposed to name the motif 16189, 16217, 16247 and 16261 the “Polynesian motif” (now described as B4a1a1a). Most probably, albeit debatably, the first appearance of the Polynesian motif may have taken place in western ISEA. The group of people bearing the motif rapidly dispersed eastward into ISEA 6 300 YBP to 5 500 YBP[7],[27],[28],[35]. After a long sojourn in PNG and near Oceania, ∼3 500 YBP, B4a1a1a spreads all over the Pacific where the “Polynesian motif” was first described. There still remain many problematic linguistic, archaeological, cultural and genetic debates. Today most accepted theories distinguish the fate of Neolithic agriculturists and Austronesian speakers, and propose that Austronesian speakers find their origin in Taiwan[36]–[39]. Some studies have described a rapid eastward dispersal (the “Express train” model) of Austronesian-speaking migrants whose language is ancestral to that of all modern Polynesians [27],[28],[40]. The sequence of event offered in this hypothesis correlates well with the Phylogeography of the “Polynesian motif” (origin and expansion of B4a1a in western ISEA and Taiwan, and then expansion of B4a1a1 and B4a1a1a in near Oceania), but the timing of these events remains questionable. Others, proponents of the “Slow boat” model, used a genetic approach, and showed that most Polynesian lineages derived from a staging post in Wallacea (West Indonesia), pre-established in the early Holocene or before[41]. The same team now proposes a more important early Holocene staging in Near Oceania (8 000 YBP) predating the Lapita cultural complex which appeared in Melanesia and the Pacific islands between 3 600 and 2 900 years ago, and the colonization of the Pacific (data acceptable for publication by Soares et al.). Another alternative suggesting backward migration from Melanesia was discussed by Hagelberg[42]. In the following, only the ISEA eastward migration will be discussed. Figure 2 utilizes two uni-parental systems. The Y-SNP data was obtained from the literature and the mtDNA data was obtained from the Taiwan dataset and the literature [5],[7],[19],[43]. This data shows that, except for time, “Express train” and “Slow boat” models can be spatially and sequentially compatible.

Figure 2. Eastward gene flow from Taiwan and west island southeast Asian (ISEA), with conservation of the initial mtDNA gene pool (the “Express train” model) and replacement of the initial Y chromosome gene pool (Y penetrance, the “Slow boat” model). The model assumes an initial flotilla of boats carrying a matrilocal society. Here Taiwan is seen as one of the hypothetical dispersal centers of the Austronesian speakers (a similar associated genetic model can be drawn when starting from the Philippines, Borneo or Sulawesi). It is proposed that the conservation and the variation of the two profiles (mtDNA and Y chromosome respectively) occurred simultaneously. At the time of leaving Papua New Guinea (∼2 500 YPB), the Polynesian ancestors have become a patrilocal society[32]. The “Express train” model is genetically associated with an almost total conservation of the matrilineal initial gene pool and the “Slow boat” model is associated with an almost total replacement of the Y chromosome initial gene pool. Following the same path throughout ISEA, cultural diffusion (Austronesian language and earth wares) most possibly reached its optimum penetrance later in time in the process. The first 3 000 years (i.e. 5 500 YBP) is a dating associated with the “Out of Taiwan” model and is in conflict with the genetic dating shown in the top right insert. A more modern hypothesis places the first appearance of the Polynesian motif and its major expansion in Near Oceania ∼6000 YBP where all subsequent movements of its bearers, eastward toward Polynesia and westward toward Madagascar, later occurred. Sequences accession numbers were obtained from Phylotree[16].

The B4ala scenario

The mtDNA scenario in Figure 2[7] describes the gene fixation of one clade (circle inserted in top right of Figure 2 showing B4a1a). All succeeding mutations occur in a group of peoples who were (or later became) Austronesian speakers and were migrating eastward toward PNG and Polynesia. The model assumes several coastal settlements, occurrence of bottle necks and founding events, and conservation of the initial maternal mtDNA gene pool as expected from a matrilocal society (where females always remained in the same clan). Four stages are shown as follows.

(1) A pre-Neolithic sailing group of Proto-Austronesians, all initially bearing haplogroup B4a1a. B4a1a is a descendant of continental East Asian haplogroup B4a1 and while offshore from mainland Asia has acquired a series of mutations (nps 6719, 12239, 15746, and 16519) that are unique (“fixed”) among insular west Asians (Taiwan and west ISEA). B4a1a is circled in the insert of Figure 2 and its bearers or descendents are represented in Pink in the flotilla.

(2) The first stage of dispersal of B4a1 a shows no mtDNA changes as Taiwan and/or west ISEA populations have similar mtDNA profiles, and women remain in their initial clan.

(3) Approximately 6 200 YBP, most likely within a region including Borneo, South Philippines, and Sulawesi[44], one of the B4a1a bearers acquired a single mutation (np 14022)[5]. In the text, haplogroup B4a1a1 will be referred as the proto-Polynesian motif.

(4) Very shortly after, one B4a1a1 individual acquired np 16247. This new type was first observed by Sykes et al.[29] and Hill et al.[45] in Borneo and Sulawesi respectively and is prominent in PNG. It is now named B4a1a1a or the Polynesian motif (note that nps 14022 and 16247 have never been seen in Taiwan).

On the eastward passage, while B4a1a quickly decreases by drift, B4a1a1 and B4a1a1a successfully continue their eastward dispersal. Coastal Papua New Guinea would have been reached ∼3 000 YBP, and then colonization of the Pacific would have culminated in the discovery of Aotearoa (New Zealand) less than 1 000 YBP[46],[47] with the arrival of the Maoris. Most importantly, after an important period of expansion in Melanesia, and including the presence of new variants of B4a1a (B4a1a1 and B4a1a1a), the original matrilineal gene pool (stage 1) remained almost identical to the final matrilineal gene pool (stage 5).

In short, matrilineal conservation of the initial gene pool, language and culture is compatible with the concepts pictured by the “Express train” or “Out of Taiwan” models.

The Y Penetrance

The Y chromosome scenario in Figure 2 describes the progression for replacement of the initial paternal gene pool of Austronesian-speaking migrants by locally acquired Melanesian genes. We must recall here that the Y-SNP genetic profile of the TwA and ISEA islanders (haplogroup O and its subtypes) differs greatly from the profile of the Melanesian populations (haplogroups F, G, H, K and C). These Melanesian haplogroups, found in an increasing cline from ISEA to New Guinea and Near Oceania, still bear the Y-SNP signature of the first Paleolithic settlers who initially crossed ISEA, coming directly from Africa and following the southern coastal route. The following scenario is shown in Figure 2:

Stages 1 to 2: The changes in the Y gene pool (blue arrow) are not yet noticeable as the Y-SNP genetic profiles of Taiwan and the Philippines are very similar.

Stages 3 and 4: Two of the 3 migrant haplogroups have been replaced by Melanesian haplogroups while haplogroup 03 still remained. 03 and 01 are frequent in Taiwan and western ISEA. 03 appears to be more successful than 01. Perhaps 03 was predominant among the migrating float of Austronesian speakers. Alternatively 03 may have been retained as the result of drift to the detriment of 01 most likely because of the low number and low Y-SNP polymorphism of the sailing migrants. Interestingly, the introduction of new haplogroups into the migrating clan supports the outcome expected from a matrilocal society on the move (the mothers of the community remain in the clan and have the leading role in determining the movement of males in and out the clan). Here “matrilocal society” is taken in the sense where genetically, heredity is traced through the female line, and where a male who does not come back to the clan after a war or hunting accident, can be replaced by autochthonous Melanesians who later will actively contribute to the continuum of the matrilocal society without altering excessively the initial organization. Their progenies will be completely integrated into the primary structure, as a result the initial Y gene pool will be totally replaced (by Melanesian genes).

Stage 5: The final patrilineal gene pool is different from the original gene pool. Moreover, and unexpectedly, after its departure from PNG, the social organization of the Austronesian has become a patrilocal society[32] but language has remained Austronesian. (This stage constitutes the last stepping stone before the big Polynesian Diaspora into the Pacific.)

In short, sequential and progressive patrilineal loss of the initial NRY gene pool, but not of language and culture, are compatible with the “Slow boat” model.

According to the genetic scenario of Figure 2, opposed models, the cultural “Out of Taiwan” and the genetic “Slow boat” models, happened conjointly. Nonetheless, mean point estimates of the timing of the genetic events remained in conflict with the cultural model (the “Out of Taiwan”). Genetically, the eastward movement of people out of Taiwan/western ISEA does not appear as recent as proposed by the classical 5 500 YBP event for the “Out of Taiwan” [48]. This conflicting aspect with genetics may be resolved if one considers the confidence intervals rather than the point estimates of these calculations. Phylogeographic analysis of mtDNA haplogroup B in East Asia [7],[35] described a continuous set of events which started with a dispersal of people (between 13 000 YBP and 8 000 YBP) who were bearers of a Taiwan or western ISEA mtDNA haplogroup (B4a1a). Although B4a1a ancestor (B4a1) comes from MSEA, B4a1a has never or rarely been seen in Mainland Asia. The two next descendents of B4a1a (the proto-Polynesian motif in western ISEA, B4a1a1, and shortly after the Polynesian Motif, B4a1a1a) appeared very closely, in succession to each other, within a 95% confidence interval of 3 000 YBP to 12 000 YBP that is in agreement with the estimate of 5500 YBP [48]. At the same time, the distribution pattern of B4a1a haplogroups (and its subtypes) suggested that a matrilineal society (speakers of Malayo-Polynesian languages) reached coastal Papua New Guinea 3 500 YBP to 2 500 YBP during the Lapita period where they rapidly expanded[49]. The colonization of the rest of the Pacific islands took place during the next 2 500 years. In this scenario, characterization of historical events estimated from genetic data are crude approximations resulting from the influence of reproductive patterns, isolation, genetic mutation, population admixture, drift, founder effect, and expansion and divergence lag times. Actually, the 95% confidence intervals obtained incorporates the cultural model but the genetic scenario still appears to antedate the time generally accepted by “Out of Taiwan” model[48]. A better fit can be obtained if firstly allowing for a demographic lag time (the time necessary for the establishment of an effective population size varying from 400 to 2 000 years), and secondly, allowing for the time in which a new mutation may reach fixation (in most cases ∼1 000 years).

In any case, the sequence of genetic events presented in this study corresponds with archaeological and linguistic observations, and supports the suggestion[32] that the main line of mutations of mtDNA (the eastward gene flow with the mutation of haplogroup B4a1a to B4a1a1 and then to B4a1a1a), the main line of linguistic patterns (Formosan to Malayo-Polynesian to Polynesian languages) and the cultures affinities (Taiwan “horticulturalists” ceramic Coarse Corded Ware culture to Lapita potteries)[48],[50] reflect a sound maternal dispersal in ISEA that is independent to geographical distances, and is overlaid by a continuously changing male-biased gene flow. As a conclusion, it appears that the genetic lay out was already established when new cultural processes (the spread of people from western ISEA, their Austronesian languages, pottery wares, and so on) started their eastward spread toward Near Oceania. It is only during the conquest of the Pacific in the last 2500 years that genes and culture correlate.

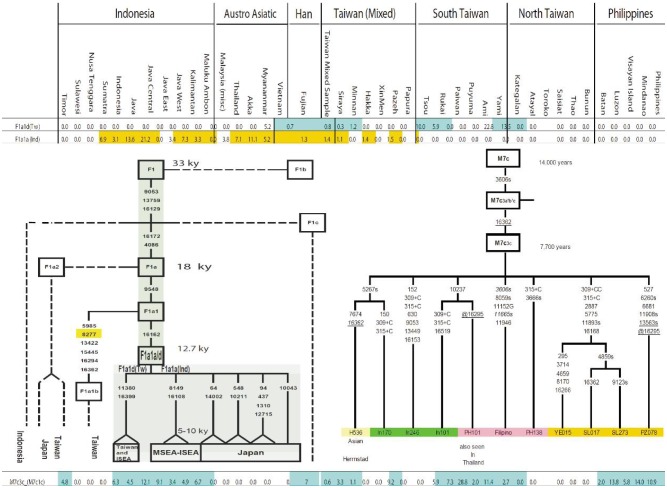

Haplogroups F1a1a and M7c3c

MSEA is mostly populated with Daic- (in the southeast) and Austro-Asiatic–(throughout Indochina) speaking populations. The most common haplogroups among Daic are B4a, F1a, M7b1, B5a, M7b*, R9a, R9b, M7c, and other undefined M* in order of frequency, totaling 48.8%[3]. Among Austro Asiatic speakers, the most common haplogroups in order of frequency are F1a, M*, D*, F1b, N*, C, M7b*, M7b1, F1a1, M7c and B4a[3],[51]. Noticeably, the two regions share low frequency sub-haplogroups of B4a*, F1a1* and M7c* which are also seen in Insular Asia (the star meaning “including other subclade determinants”). This indicates that Austro-Asiatic speakers, Daic and Insular Asia islanders (TwA, Filipino and Indonesians), share deep ancestry most likely dating more than 20 000 YBP. Indeed, we have just described B4a1a in ISEA that descended from MSEA haplogroup B4a1 whose coalescence age in MSEA would date ∼29 000 YBP.

In their phylogeographic reconstruction[3],[26],[43] researchers proposed a bidirectional move ment of people from MSEA toward insular Asia via either the Taiwan straight, or southward to western ISEA along the Indochinese peninsula and Indonesia. These two processes would then later join in an eastward migration toward PNG.

Haplogroup F1a1a was initially defined by Hill[19],[45] as a daughter clade of F1a1 (Figure 3). Dating estimate of this clade indicates a candidate for both postglacial and Neolithic dispersals. F1a1a, defined by nps 8149 and 16108, provides a distinctive patterns [shown as F1a1a (Ind) in Figure 3]; it is seen in both South China and Indochina, having first appeared 5 000 YBP to 10 000 YBP. It is most common among in Indochina and among some of the indigenous groups of peninsular Malaysia[19],[45]. Trejaut et al.[7] and Tabbada et al.[5] saw a sister clade of F1a1a, here defined by nps 11380 and 16399 and named F1a1d(Tw). F1a1d(Tw) is found in MSEA, North Vietnam, Fujian and Taiwan (Figure 3). Neither F1a1a (Ind) nor F1a1d(Tw) is seen in the Philippines or among north TwA. The presence of other subclades of F1a1 in several regions of MSEA, Indochina and Japan indicates that MSEA (having the highest diversity of F1a1) is most likely the site of origin of F1a1. It is from there that the two sister clades F1a1d(Tw) and F1a1a(lnd) must have left MSEA 9 000 YBP and separately reached Taiwan and western ISEA respectively.

Figure 3. Haplogroup F1a1a and M7c3c distribution. Distribution of F1a1d (Tw) is shown in blue and F1a1a (Ind) is shown in orange (top of Figure 3). The overlapping of the two distributions suggests a probable origin of precursor F1a in mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA) where the frequency and diversity of subtypes of F1a are the highest. Distribution of M7c3c is seen throughout island Southeast Asia (ISEA), but not in MSEA where it must have disappeared by drift. Alternatively M7c3c could have its origin in ISEA where it quickly expanded and dispersed throughout western ISEA and Taiwan. Subtypes of M7c7c have developed in isolation and have rarely moved away from their location of origin. Tw, the Taiwan type; Ind, the Indonesian type.

Haplogroup M7c3c, dating to ∼8 000 YBP (Figure 3), is not seen in MSEA. The presence of its sister clades and that of its direct ancestor (M7c3) in MSEA and Japan indicates a late Pleistocene origin of the M7c ancestral clade on the East Asian continent. The distribution of M7c3c (Figure 3) throughout Taiwan and ISEA correlates with the spread of the Austronesian speakers, but the spread only reached Near Oceania and did not expand to Polynesia. There is a lot of variation among the sister branches of M7c3c, most interestingly, these subtypes are not shared between regions nor do any branches indicate later subsequent migrations. This probably indicates that after an initial expansion, M7c3c was rapidly distributed throughout ISEA and remained isolated till present time, a period which allowed diversity to develop locally. The higher frequency of M7c3c in Taiwan and the Philippines than in Indonesia would support a dispersal model similar to the “Out of Taiwan” model. Nonetheless these two factors are not sufficient to determine the origin of the first M7c3c. Actually except for the distribution of M7c3c in Taiwan and Indonesia, the highest frequency and diversity of M7c3c in the Philippines could also indicate a bidirectional gene flow of M7c3c from North and South into the Philippines from a location (in MSEA) that has now lost M7c3c by drift.

In the two preceding paragraphs we first saw that F1a1d(Tw) and F1a1a(lnd) showed opposed directional gene flows (North and South respectively) that reached Taiwan and Indonesia, but did not reach the Philippines. The tracing of these routes on a map clearly delineates a demographic pincer model that could have started in pre-Holocene era in MSEA. Secondly, we saw that an origin of M7c3c could not be localized but it was clearly shown that its distribution covered the whole western ISEA (ending in Near Oceania) and that the origin of its founder (M7c3) most likely located in MSEA. As for F1a1d(Tw) and F1a1a(lnd), the subtypes of M7c3c were distinct between regions and the higher diversity in the Philippine supports the demographic pincer model of distribution just mentioned. This model does not oppose the B4a1a model of distribution which we proposed initially. Actually, the B4a1a model followed much more closely the M7c3c distribution as all subtypes of B4a1a were sedentary in western ISEA except for one (B4a1a1 and later B4a1a1a) whose demography can be retraced further into the Pacific and much later in the Indian Ocean[52].

In support of this pincer model of distribution, Li et al.[53] used human Y-SNP to show that Taiwanese and Indonesians were derived from MSEA populations (see Figure 2 of reference [54]). Also, using Y-SNP Karafet et al.[54] and Trejaut et al. (materials in preparation) were able to estimate a date of the demographic branches of the pincer model[55]. For this, they used the polymorphism of Y short tandem repeats acquired in the background of each Y-SNP haplogroup: O1a*, O1a1*, O3a*, O3a3* and O3a4*. They showed that the longest isolation of Taiwan or ISEA from a single founder haplogroup in MSEA dated between 12 000 YBP and 20 000 YBP. The upper range of these dates appears older than dating obtained from mtDNA lineages[4],[5],[7] and could be due to the slower rate of mutation of Y-SNP. Alternatively the older dating could also reflect a period of expansion (a lag time) of these Y-SNP haplogroups in MSEA when people were awaiting more favorable climatic conditions for their opposite migrations to Taiwan and ISEA.

Finally more support to the pincer model is given by a large-scale survey of autosomal variation from a broad geographic sample of Asian human populations[56],[57]. The study (only based on phylogeography but not on time) showed that the di stribution of populations throughout insular Asia was strongly correlated with linguistic, genetic affiliations as well as geography by showing that gene flow from SEA constituted a major geographic source of all insular Asian populations.

Conclusion

Considerable differentiations between populations of East Asia and ISEA have been genetically determined. Using mtDNA and non recombining Y chromosome, some of these genetic differentiations could be dated back to the out of Africa era 60 000 YBP, a time representing the origin of all extant populations in the northern hemisphere. A time also when anatomically modern humans were already carriers of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and when one do not know if the Oncogene region on EBV DNA was differentiated, active or not active. The distribution of southern Asian populations throughout the world has been associated with NPC[1] and with that of specific type of EBV[58]. It is possible that the mutated form of EBV associated with NPC occurred 45 000 ago when people from the horn of Africa reached Sundaland and dispersed North and East. The northern group, later the mongoloids, under climatic and geographic constraint, remained isolated for more than 30 000 years. This period (of selective pressure) gave ample time for the EBV strain among Asian people to evolve as a lineage distinct from those of Papua New Guinea, Australian or isolates of the rest of the world. NPC due to EBV is rare in Europeans but common in southern Chinese who, even in the farthest-reached regions (New Zealand, Easter Island or even Africa) are associated to presence of NPC among the autochthones (e.g. the Maoris people, the Moroccans). Although susceptibility loci have been mapped within the human genome, the etiological factors associated with EBV are remarkable. It is possible that it is this association with a specific EBV strain and genes of the human genome that should be studied further.

References

- 1.Wee JTS, Ha TC, Loong SLE, et al. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Is Nasopharyngeal Cancer really a Cantonese Cancer? [J] Chin J Cancer. 2009;28(12):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin M, Chu CC, Chang SL, et al. The origin of Minnan and Hakka, the so-called “Taiwanese”, inferred by HLA study [J] Tissue Antigens. 2001;57(3):192–199. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057003192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Cai X, Winograd-Cort ER, et al. Mitochondrial DNA diversity and population differentiation in southern East Asia [J] Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;134(4):481–488. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soares P, Trejaut JA, Loo JH, et al. Climate change and postglacial human dispersals in Southeast Asia [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25(6):1209–1218. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabbada KA, Trejaut J, Loo JH, et al. Philippine mitochondrial DNA diversity: a populated viaduct between Taiwan and Indonesia? [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(1):21–31. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tajima A, Sun CS, Pan IH, et al. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in nine aboriginal groups of Taiwan: implications for the population history of aboriginal Taiwanese [J] Hum Genet. 2003;113(1):24–33. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trejaut JA, Kivisild T, Loo JH, et al. Traces of archaic mitochondrial lineages persist in Austronesian speaking Formosan populations [J] PloS Biol. 2005;3(8):e247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun C, Kong QP, Palanichamy MG, et al. The dazzling array of basal branches in the mtDNA macrohaplogroup M from India as inferred from complete genomes [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(3):683–690. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster P. Ice Ages and the mitochondrial DNA chronology of human dispersals: a review [J] Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359(1142):255–264. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdulla MA, Ahmed I, Assawamakin A, et al. Mapping human genetic diversity in Asia [J] Science. 2009;326(5959):1541–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.1177074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudjashov G, Kivisild T, Underhill PA, et al. Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis [J] Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(21):8726–8730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702928104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedlaender J, Schurr T, Gentz F, et al. Expanding Southwest Pacific mitochondrial haplogroups P and Q [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(6):1506–1517. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forster P, Torroni A, Renfrew C, et al. Phylogenetic star contraction applied to Asian and Papuan mtDNA evolution [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18(10):1864–1881. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedlaender JS, Friedlaender FR, Hodgson JA, et al. Melanesian mtDNA complexity [J] PLoS One. 2007;2(2):e248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CL, Trejaut J, Lin M, et al. 2009 International Symposium of Austronesian Studies. Taiwan: National Museum of Prehistory; 2009. Three ancient DNA studies from different sites in Taiwan [C]. pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Oven M, Kayser M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation [J] Hum Mutat. 2009;30(2):E386–E394. doi: 10.1002/humu.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mona S, Grunz KE, Brauer S, et al. Genetic admixture history of Eastern Indonesia as revealed by Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA analysis [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(8):1865–1877. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trejaut JA, Lee CL, Yen JC, et al. 19th Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Congress IPPA 2009. Hanoi (Vietnam): Institute of Archeology, Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences; 2009. Mitochondrial, Y chromosome and an ancient DNA molecualr analysis in Taiwan in island Southeast Asia [C] p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill C, Soares P, Mormina M, et al. A mitochondrial stratigraphy for island southeast Asia [J] Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(1):29–43. doi: 10.1086/510412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tajima A, Hamaguchi K, Terao H, et al. Genetic background of people in the Dominican Republic with or without obese type 2 diabetes revealed by mitochondrial DNA polymorphism [J] J Hum Genet. 2004;49(9):495–499. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endicott P, Gilbert MT, Stringer C, et al. The genetic origins of the Andaman Islanders [J] Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(1):178–184. doi: 10.1086/345487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thangaraj K, Singh L, Reddy AG, et al. Genetic affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a vanishing human population [J] Curr Biol. 2003;13(2):86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macaulay V, Hill C, Achilli A, et al. Single, rapid coastal settlement of Asia revealed by analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes [J] Science. 2005;308(5724):1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1109792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thangaraj K, Sridhar V, Kivisild T, et al. Different population histories of the Mundari- and Mon-Khmer–speaking Austro-Asiatic tribes inferred from the mtDNA 9-bp deletion/insertion polymorphism in Indian populations [J] Hum Genet. 2005;116(6):507–517. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trejaut JA, Loo JH, Lee CL, et al. Antiquated mtDNA lineages found in ISEA trace back to first modern human migrations [C] In: Institute of Human Genetics, editor. In Genomics for Better Health In the AsiaPacific. Joint 7th Human Genome Organisation (HUGO)-Pacific Meeting and the 8th Asia-Pacific Conference on Human GeneticsCebu, Philipp. Manila: National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines; 2008. pp. SS24–FP24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordaux R, Deepa E, Vishwanathan H, et al. Genetic evidence for the demic diffusion of agriculture to India [J] Science. 2004;304(5674):1125. doi: 10.1126/science.1095819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melton T, Peterson R, Redd AJ, et al. Polynesian genetic affinities with Southeast Asian populations as identified by mtDNA analysis [J] Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57(2):403–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redd AJ, Takezaki N, Sherry ST, et al. Evolutionary history of the COII/tRNALys intergenic 9 base pair deletion in human mitochondrial DNAs from the Pacific [J] Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12(4):604–615. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sykes B, Leiboff A, Low-Beer J, et al. The origins of the Polynesians: an interpretation from mitochondrial lineage analysis [J] Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57(6):1463–1475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagelberg E. Ancient and modern mitochondrial DNA sequences and the colonization of the Pacific [J] Electrophoresis. 1997;18(9):1529–1533. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soodyall H, Vigilant L, Hill AV, et al. mtDNA control-region sequence variation suggests multiple independent origins of an “Asian-specific” 9-bp deletion in sub-Saharan Africans [J] Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58(3):595–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cann RL, Lum JK. Dispersal Ghosts in Oceania [J] Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16(4):440–451. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagelberg E, Quevedo S, Turbon D. DNA from ancient Easter Islanders [J] Nature. 1994;369(6475):25–26. doi: 10.1038/369025a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lum JK, Rickards O, Ching C. Polynesian mitochondrial DNAs reveal three deepmaternal lineage clusters [J] Hum Biol. 1994;66(4):567–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierson MJ, Martinez-Arias R, Holland BR, et al. Deciphering past human population movements in Oceania: provably optimal trees of 127 mtDNA genomes [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(10):1966–1975. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellwood P. A hypothesis for Austronesian origins [J] Asian Perspective. 1984–1985;26(1):107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blundell D. Language connecting the world. Berkeley, CA: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum, University of California; 2000. “Austronesian Taiwan” linguistics, history, ethnology, prehistory [M] pp. 401–459. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blust R. Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics [M] In: Zeitoun E, Li PJK, editors. Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian linguistics. Taipei: Academia Sinica; 1999. pp. 31–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li PJK. Formosan languages: the state of the art [M] In: Blundel D, editor. Austronesian Taiwan: linguistics, history, ethnology, prehistory. Berkeley CA: Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California; 2000. pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diamond J, Bellwood P. Farmers and their languages: the first expansions [J] Science. 2003;300(5619):597–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1078208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oppenheimer S, Richards M. Fast trains, slow boats, and the ancestry of the Polynesian islanders [J] Sci Prog. 2001;84(Pt 3):157–181. doi: 10.3184/003685001783238989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hagelberg E, Cox MP, Schiefenhovel W, et al. A genetic perspective on the origins and dispersal of the Austronesians from Madagascar to Easter Island [M] In: Sanchez-Mazas A, Blench R, Malcolm D, et al., editors. Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics. London: Routlegde (Oxon); 2008. pp. 356–375. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karafet TM, Hallmark B, Cox MP, et al. Major east-west division underlies Y chromosome stratification across Indonesia [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(8):1833–1844. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oppenheimer SJ, Richards M. Polynesian origins. Slow boat to Melanesia? [J] Nature. 2001;410(6825):166–167. doi: 10.1038/35065520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill C, Soares P, Mormina M, et al. Phylogeography and ethnogenesis of aboriginal southeast asians [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(12):2480–2491. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green RC. Near and remote Oceania: disestablishing “Melanesia” in culture history [M] In: Pawley A, editor. Man and a half: essays in Pacific anthropology and ethnobiology in honour of Ralph Bulmer. Auckland, New Zealand: The Polynesian Society; 1991. pp. 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirch PV. London: University of California Press; 2000. An archaeological history of the Pacific Islands before European contact [M] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bellwood P, Dizon E. The batanes archaeological project and the “Out of Taiwan” hypothesis for Austronesian dispersal [J] J Austronesian Studies. 2005;1(1):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hage P, Marck J. Matrilineality and the Melanesian origin of Polynesian Y chromosomes [J] Curr Anthropol. 2003;44(S5):121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsang CH. Taipei: Council for Cultural Affairs. 1995 Chinese ed. Taiwan Archaeology. Taipei: Ministry of Cultural Affairs, ROC, Government Information Office; 2000. The Archaeology of Taiwan [M] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gan RJ, Pan SL, Mustavich LF, et al. Pinghua population as an exception of Han Chinese's coherent genetic structure [J] J Hum Genet. 2008;53(4):303–313. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tofanelli S, Bertoncini S, Castri L, et al. On the origins and admixture of Malagasy: new evidence from high-resolution analyses of paternal and maternal lineages [J] Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(9):2109–2124. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Wen B, Chen SJ, et al. Paternal genetic affinity between Western Austronesians and Daic populations [J] BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Meilerman MB, et al. New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree [J] Genome Res. 2008;18(5):830–838. doi: 10.1101/gr.7172008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saillard J, Forster P, Lynnerup N, et al. mtDNA variation among Greenland Eskimos: the edge of the Beringian expansion [J] Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(3):718–726. doi: 10.1086/303038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium. Abdulla MA, Ahmed I, et al. Maping human genetic diversity in Asia [J] Science. 2009;326(5959):1541–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.1177074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Normile D. SNP study supports Southern migration route to Asia [J] Science. 2009;326(5959):1470. doi: 10.1126/science.326.5959.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burrows JM, Bromham L, Woolfit M, et al. Selection pressure-driven evolution of the Epstein-Barr virus–encoded Oncogene LMP1 in virus isolates from Southeast Asia [J] J Virol. 2004;78(13):7131–7137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7131-7137.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]