Abstract

P21 (CDKN1A), a key cell cycle regulatory protein that governs cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase, can regulate cell proliferation, growth arrest, and apoptosis. The Ser31Arg polymorphism is located in the highly conserved region of p21 and may encode functionally distinct proteins. Although many epidemiological studies have been conducted to evaluate the association between the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk, the findings remain conflicting. This meta-analysis with 33 077 cases and 45 013 controls from 44 published case-control studies showed that the variant homozygous 31Arg/Arg genotype was associated with an increased risk of numerous types of cancers in a random-effect model (homozygote comparison: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.37, P = 0.0002 for the heterogeneity test; recessive model comparison: OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.33, P = 0.0001 for the heterogeneity test). Stratified analysis revealed that increased cancer risk associated with the 31Arg/Arg genotype remained significant in subgroups of colorectal cancer, estrogen-related cancer, Caucasians, population-based studies, studies with matching information or a larger sample size. Heterogeneity analysis showed that tumor type contributed to substantial between-study heterogeneity (recessive model comparison: χ2 = 21.83, df = 7, P = 0.003). The results from this large-sample sized meta-analysis suggest that the p21 31Arg/Arg genotype may serve as a potential marker for increased cancer risk.

Keywords: p21, cancer, risk, meta-analysis

The cell cycle regulates growth and differentiation, and defects in cell cycle control are a hallmark of cancer development[1]. Phase progression is principally regulated by Cyclins, Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and CDK inhibitors (CKIs)[2]. Cyclins and CDKs form complexes regulating cell growth by cell cycle control, whereas CKIs inhibit the activities of the complexes and induce cell cycle arrest[3],[4]. P21 protein belongs to the Cip/Kip family of CKIs and inhibits the phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) protein by interfering with cyclin E–CDK2 or cyclin A–CDK2 complex[5],[6].

P21 (Cdkn1a/Waf1/Cip1) is encoded by the CDKN1A locus on chromosome 6p21.2 and has a p53 transcriptional regulatory motif. Studies have shown that p21 is a critical downstream effector in the p53-specific pathway of growth control, and the expression of p21 is directly regulated by p53 in response to DNA damage, leading to cell cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint[7]. As p21 inhibits proliferation[8] and acts as one of the major transcriptional targets of p53[7], it was initially considered as a potential tumor suppressor. However, studies have also reported that p21 could act as an Oncogene because of its antiapoptotic activities[9]–[11]. Alterations in p21 expression have been observed in a wide variety of cancers, including breast, lung, cervical, ovarian, liver, uterine, and head and neck cancers[12]–[17], indicating the importance of p21 in Carcinogenesis.

Although the involvement of p21 in tumor formation is evident, mutations in p21 are very rare[18],[19]. Thus, most reports focus on genetic variants of p21, and genotypes of some functional polymorphisms have shown to be associated with a high risk of different types of cancer[20]–[22]. The most frequently investigated polymorphism of p21 is Ser31Arg (rs1801270C > A), with a base change from C to A resulting in a non-synonymous serine to arginine substitution in the protein[23], causing a loss of the Blpl restriction site and affecting the DNA-binding zinc finger motif[22]. Hence, it is likely that p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism may result in the alteration of p21 e xpression and/or activity, thereby affecting susceptibility to cancer.

Many molecular epidemiological studies have been conducted to evaluate the effect of the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism on cancer risk[19],[24]–[70]. The results, however, remain conflicting, and the underlying heterogeneity between studies still needs to be explored. To estimate the overall cancer risk associated with the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and to quantify potential between-study heterogeneity, we conducted a systematic meta-analysis by including the most recent and relevant studies focusing on the association between the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Identification and eligibility of relevant references

We included all references of the case-control studies written in English and published to date on the association between the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk. Two electronic databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE) were searched (last search update October 2010, using the search terms “p21” or “CDKN1A”, “cancer” or “carcinoma”, and “polymorphism” or “variant”) to identify eligible references. Additional references were identified by a hand search of original papers or reviews. If studies had overlapping subjects, only the one with the larger or largest sample size was selected. Furthermore, the studies including subjects with family history or cancer-prone predisposition were excluded.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each report: author, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, demographics, cancer type, and detail genotyping information and source of controls (population-based and hospital-based). For studies including subjects of different racial descents, data were extracted separately for each race (categorized as Caucasian, Asian, and others).

Statistical analyses

Genotype frequency was collected from each study to evaluate the risk of cancers [odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)]. For all studies, we evaluated the effects of variant genotypes including Arg/Ser and Arg/Arg, compared with the wild-type Ser/Ser genotype, respectively. Then we calculated the ORs and 95% CI for both dominant and recessive genetic models of the variant Arg allele. In addition, we conducted stratification analysis by tumor type (if one cancer type was investigated in less than 3 studies, it would be merged into the “other cancers” group), ethnicity, control source, matching status (yes or no), and sample size ( < 500, 500 to 1000, and > 1000). Smoking-related cancers included lung, bladder, head and neck, kidney, and pancreatic cancers; estrogen-related cancers included breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers.

The χ2-based Q statistic test was used to assess between-study heterogeneity, and it was considered significant if P < 0.05[71]. The fixed-effects model and the random-effects model were respectively performed to combine values from each of the studies based on the Mantel-Haenszel method and the DerSimonian and Laird method[72]. When the effects were assumed to be homogenous, the fixed-effects model was then used; otherwise, the random-effects model was more appropriate. The inverted funnel plots and Egger's test were used to investigate publication bias (linear regression analysis)[73]. The deviation of genotype distribution from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) among controls was also examined by a goodness-of-fit χ2 test. All analyses were conducted using Review Manage (v.5.0) and Stata 10.0. P values were two-sided.

Results

Characteristics of studies

A total of 48 publications examined the relationship between p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk. Two studies[24],[25] were excluded because they investigated the same or a subset population of reported articles[65],[30]. Another two were also excluded because they did not present detailed genotyping information[69] or had cancer-prone predisposition[70]. The studies investigating different cancers[38], multiple ethnicity[26], or multi-center collaboration[30] were separated into multiple studies in subgroup analysis. In addition, three studies [48],[61],[68] that only provided the total number of variant genotypes (Arg/Ser and Arg/Arg) were included in the analysis for the dominant model but not for other genetic models. Finally, our meta-analysis consisted of 44 publications including 59 case-control studies: 20 breast cancer studies, 5 lung cancer studies, 6 head and neck cancer studies, 7 cervical cancer studies, 3 colorectal cancer studies, 3 skin cancer studies, 5 gastric and esophageal cancer studies, and 10 studies of other cancers (Table 1). Among the 59 studies, 28 were conducted in Caucasian descents, 28 were conducted in Asian descents, 2 were conducted in other descents, and the remaining one by Keshava et al.[26] was divided into two subgroups (Caucasians and other ethnicity), because it included multiple ethnicities. In addition, 11 studies were population-based and 48 were hospital-based; 26 did not provide matching information, while 33 were matched by age, sex, and/or geographic region. The polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay (PCR-RFLP) was the most frequently used method for genotyping. Some other methods were also applied, such as direct sequencing, Taqman, and SNaPshot (Table 1). Overall, most studies indicated that the distribution of genotypes in controls was consistent with HWE with the exception of 6 studies[19],[26],[40],[43],[47],[59].

Table 1. Characteristics of the 44 references included in the meta-analysis.

| Reference | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Cancer type | Sample size (case/control) | Matching (yes/no) | Genotyping method | Source of control |

| Keshava et al.[26] | 2002 | USA | Multiple | Breast cancer | 160/327 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Ma et al.[27] | 2006 | China | Asian | Breast cancer | 368/467 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Tarasov et al.[28] | 2006 | Russia | Caucasian | Breast cancer | 151/191 | No | PCR-RFLP and dCAPs | Hospital |

| Staalesen et al.[29] | 2006 | Norway | Caucasian | Breast cancer | 547/1006 | No | Sequencing | Hospital |

| Cox et al.[30] | 2007 | Multiple | Caucasian/Asian | Breast cancer | 18 290/22670 | Both | Multiple methods | Both |

| MARIE-GENICA[31] | 2010 | Germany | Caucasian | Breast cancer | 3140/5472 | Yes | MALDI-TOF MS and PCR-based fragment analyses | Population |

| Sjalander et al.[32] | 1996 | Sweden | Caucasian | Lung cancer | 144/761 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Shih et al.[33] | 2000 | China | Asian | Lung cancer | 155/189 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Su et al.[34] | 2003 | USA | Caucasian | Lung cancer | 1069/1220 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Popanda et al.[35] | 2007 | Germany | Caucasian | Lung cancer | 402/403 | No | Fluorescence-based melting-curve | Hospital |

| Choi et al.[36] | 2008 | Korea | Asian | Lung cancer | 549/533 | Yes | PCR and sequencing | Hospital |

| Sun et al.[19] | 1995 | China | Asian | Nasopharyngeal cancer | 76/66 | No | PCR-SSCP direct sequencing | Hospital |

| Tsai et al.[37] | 2002 | China | Asian | Nasopharyngeal cancer | 47/119 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Rodrigues et al.[38] | 2003 | Brazil | Caucasian | Head and neck cancer; skin cancer | 73/104;46/104 | No | PCR-SSCP | Hospital |

| Li et al.[39] | 2005 | USA | Caucasian | Head and neck cancer | 712/1222 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Bau et al.[40] | 2007 | China | Asian | Oral cancer | 137/105 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Gomes et al.[41] | 2008 | Brazil | Mixed | Oral cancer | 80/80 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Roh et al.[42] | 2001 | Korea | Asian | Cervical cancer | 111/98 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Harima et al.[43] | 2001 | Japan | Asian | Cervical cancer | 66/108 | No | Sequencing | Hospital |

| Lee et al.[44] | 2004 | Korea | Asian | Cervical cancer | 185/345 | No | SNaPshot assay | Hospital |

| Lee et al.[45] | 2004 | Korea | Asian | Cervical cancer | 81/86 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Bhattacharya et al.[46] | 2005 | India | Asian | Cervical cancer | 148/191 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Tian et al.[47] | 2009 | China | Asian | Cervical cancer | 317/353 | Yes | MAMA-PCR | Hospital |

| Roh et al.[48] | 2010 | Korea | Asian | Cervical adenocarcinoma | 53/286 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Wu et al.[49] | 2003 | China | Asian | Esophageal cancer | 128/178 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Wu et al.[50] | 2004 | China | Asian | Gastric cancer | 89/192 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Lai et al.[51] | 2005 | China | Asian | Gastric cancer | 123/119 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Taghavi et al.[52] | 2010 | Iran | Asian | Esophageal cancer | 126/100 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Yang et al.[53] | 2010 | China | Asian | Esophageal cancer | 80/200 | Yes | Sequencing | Hospital |

| Polakova et al.[54] | 2009 | Germany | Caucasian | Colorectal cancer | 612/611 | Yes | Taqman | Hospital |

| Liu et al.[55] | 2010 | China | Asian | Colorectal cancer | 373/838 | No | PCR-RFLP | Population |

| Cacina et al.[56] | 2010 | Turkey | Caucasian | Colorectal cancer | 53/64 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Konishi et al.[57] | 2000 | Japan | Asian | Skin cancer | 113/165 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Li et al.[58] | 2008 | USA | Caucasian | Cutaneous melanoma | 805/838 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Hachiya et al.[59] | 1999 | Japan | Asian | Endometrial cancer | 54/55 | Yes | Dot Blot Hybridization | Hospital |

| Chen et al.[60] | 2002 | China | Asian | Bladder cancer | 53/119 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Roh et al.[61] | 2004 | Korea | Asian | Endometrial cancer | 95/285 | No | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Hishida et al.[62] | 2004 | Japan | Asian | Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | 103/440 | No | Duplex PCR-CTPP | Hospital |

| Huang et al.[63] | 2004 | China | Asian | Prostate cancer | 200/247 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Hirata et al.[64] | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Renal cell carcinoma | 200/200 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Gayther et al.[65] | 2007 | Multiple | Caucasian | Ovarian cancer | 1491/2463 | Yes | Taqman | Population |

| Rajaraman et al.[66] | 2007 | USA | Mixed | Brain tumor | 594/529 | Yes | Taqman | Hospital |

| Chung et al.[67] | 2008 | China | Asian | Urothelial carcinoma | 169/402 | Yes | PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

| Chen et al.[68] | 2010 | USA | Caucasian | Pancreatic cancer | 509/462 | Yes | Pyrosequencing and PCR-RFLP | Hospital |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphisms; dCAPs, derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry; SSCP, single strand conformation polymorphism; MAMA, mismatch amplification mutation assay; CTPP, confronting two-pair primers.

Quantitative synthesis

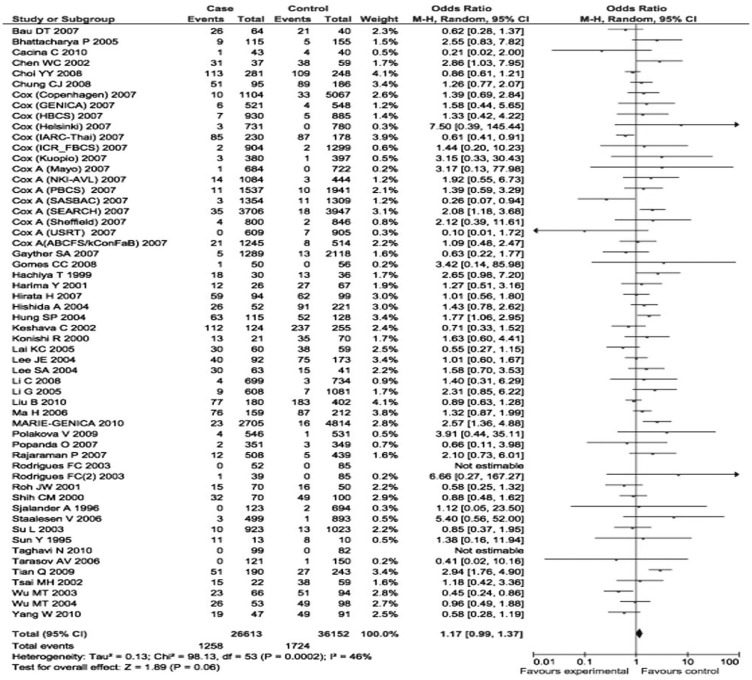

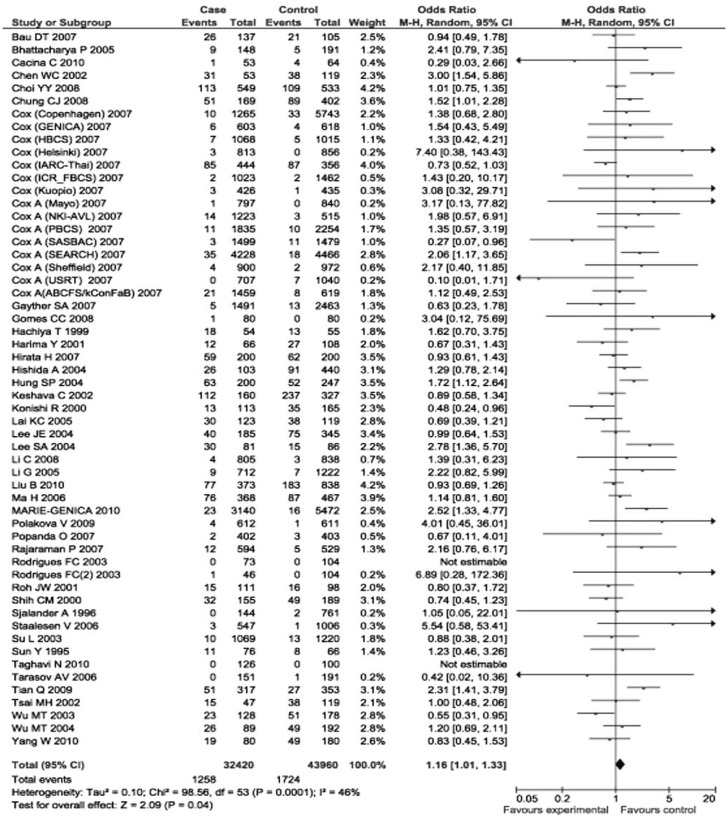

The p21 31Arg allele frequency varied in different ethnicities, ranging from 0.04 in a Caucasian population[30] to 0.54 in an Asian population[51]. When the eligible studies were pooled into the meta-analysis, the variant genotypes of p21 Ser31Arg were significantly associated with an increased cancer risk. Specifically, compared to the wild-type homozygotes (31Ser/Ser), the variant homozygotes (31Arg/Arg) had a borderline increased risk of all types of cancers (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.37, P = 0.0002 for heterogeneity test), and the association was significant in the recessive genetic model [Arg/Arg vs. (Ser/Ser + Arg/Ser): OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.33, P = 0.0001 for heterogeneity test] (Figures 1 and 2). However, such associations were not found for heterozygous comparison or for dominant model comparison (heterozygote comparison: OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.94 to 1.08, P < 0.0001 for the heterogeneity test; dominant model comparison: OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.89 to 1.08, P < 0.0001 for the heterogeneity test).

Figure 1. Forest plot (random-effects model) of overall cancer risk associated with the p21 codon 31 polymorphism: Arg/Arg vs. Ser/Ser. Compared to Ser/Ser, Arg/Arg had a borderline association with increased risk of all types of cancer.

Figure 2. Forest plot (random-effects model) of overall cancer risk associated with the p21 codon 31 polymorphism: Arg/Arg vs. (Arg/Ser+ Ser/Ser). Compared to Arg/Ser + Ser/Ser, Arg/Arg had an association with increased risk of all types of cancer.

In stratified analysis by tumor type, recessive model comparison with the heterogeneity test showed that individuals with variant homozygous genotypes (31Arg/Arg) had a higher risk for colorectal cancer (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.08, P = 0.25) and estrogen-related cancer (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.60, P = 0.002), but not for other cancers (Table 2). Furthermore, recessive model comparison for the heterogeneity test showed that the risk effect of variant homozygotes (31Arg/Arg) remained significant in studies with Caucasian subjects (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.14 to 1.73, P = 0.34), population-based controls (OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.67, P = 0.06), matching design (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.45, P = 0.002), and sample size more than 1000 (OR =1.18, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.37, P = 0.08).

Table 2. Summary ORs for association between the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk.

| Subgroup | Comparisons | Cases/Controls | Arg/Arg vs. (Arg/Ser + Ser/Ser) OR (95% CI)c | Pd |

| Totala | 56 | 32 420/43 960 | 1.16 (1.01–1.33) | 0.0001 |

| Tumor type | ||||

| Breast cancer | 20 | 22 656/30 133 | 1.25 (0.95–1.63) | 0.03 |

| Lung cancer | 5 | 2319/3106 | 0.92 (0.73–1.17) | 0.88 |

| Head and neck cancer | 6 | 1125/1696 | 1.16 (0.79–1.72) | 0.63 |

| Cervical cancer | 6 | 908/1181 | 1.40 (0.85–2.28) | 0.005 |

| Colorectal cancer | 3 | 1038/1513 | 1.39 (1.03–1.87) | 0.25 |

| Skin cancer | 3 | 964/1107 | 0.64 (0.36–1.16) | 0.15 |

| Gastric / esophageal cancer | 5 | 546/769 | 0.78 (0.58–1.03) | 0.25 |

| Other cancers | 8 | 2864/4455 | 1.43 (1.18–1.73) | 0.08 |

| Smoking–related cancer | 12 | 3574/4936 | 1.05 (0.88–1.27) | 0.10 |

| Estrogen–related cancer | 29 | 25 055/33 777 | 1.27 (1.01–1.60) | 0.002 |

| Ethnicityb | ||||

| Caucasian | 28 | 27 184/36 960 | 1.41 (1.14–1.73) | 0.34 |

| Asian | 26 | 4495/6251 | 1.09 (0.92–1.28) | < 0.0001 |

| Others | 3 | 741/749 | 0.87 (0.53–1.42) | 0.11 |

| Control source | ||||

| Population | 11 | 17623/26454 | 1.36 (1.11–1.67) | 0.06 |

| Hospital | 45 | 14797/17506 | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 0.0008 |

| Matching status | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 23 809/27 929 | 1.21 (1.01–1.45) | 0.002 |

| No | 24 | 8611/16031 | 1.09 (0.88–1.35) | 0.01 |

| Sample size | ||||

| < 500 | 25 | 2653/3827 | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 0.002 |

| 500–1000 | 8 | 2455/3522 | 1.21 (0.87–1.68) | 0.01 |

| > 1000 | 23 | 27 312/36 611 | 1.18 (1.01–1.37) | 0.08 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. aThree references that only provided the total number of Arg/Ser and Arg/Arg were excluded from the analysis for the recessive comparison [Arg/Arg vs. (Arg/Ser+Ser/Ser)]. b0ne study by Keshava et al included multiple ethnicities. cRandom effect model was used when P value for heterogeneity test < 0.05; otherwise, fix effect model was used. dTest for heterogeneity.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses

In the recessive model comparison, heterogeneity among all studies on the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and cancer risk was observed (χ2 = 98.56, P = 0.0001). We evaluated the source of heterogeneity by tumor type, ethnicity, control source, matching status, and sample size, and found that tumor type contributed to substantial heterogeneity (χ2 = 21.83, P = 0.003), but not ethnicity, control source, matching status, and sample size. The leave-one-out sensitivity analysis indicated that no single study changed the pooled ORs qualitatively. Furthermore, the exclusion of 6 studies [19],[28],[40],[43],[47],[59], whose genotype distributions deviated from HWE, did not affect the results of the meta-analysis (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.34, P = 0.0004).

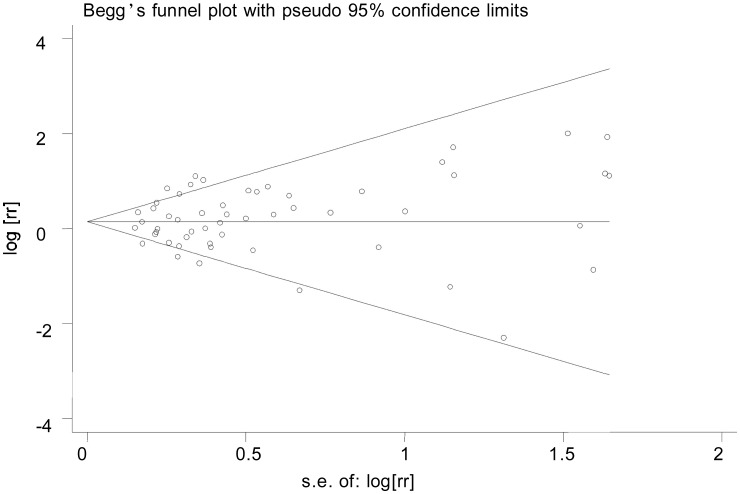

Publication bias

Funnel plot and Egger's test were conducted to access the publication bias of all studies. The shapes of the funnel plots seemed symmetrical (Figure 3), suggesting that there was no obvious publication bias. Egger's test was used to provide further statistical evidence; similarly, we did not find significant publication bias in this meta-analysis (t = 0.95, P = 0.345).

Figure 3. Funnel plot analysis to detect publication bias. Each point represents a separate study for the Indicated association.

Discussion

On the basis of 44 independent publications, our meta-analysis provided statistical evidence that variant homozygous Arg/Arg genotype of p21 was significantly associated with an increased risk of cancers, particularly of colorectal cancer and estrogen-related cancer. The stratification analysis also showed that the risk effect of Arg/Arg was more prominent in studies with Caucasian subjects, population-based controls, matching design, and larger sample sizes.

P21 is a Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, causing cell cycle arrest by inhibiting the G1 to S phase checkpoint, and it is up-regulated by the tumor suppressor protein P53[7]. In addition, p21 is frequently down-regulated in human cancer, and the loss of its expression or function has been implicated in Carcinogenesis or the prognosis of multiple cancers[12]–[17],[74]. However, studies also suggest that p21 can promote the development of cancer, indicating a double-edged effect showing tumor-suppressing or tumor-promoting properties[9]–[11]. The most common p21 polymorphism is at codon 31 (C > A) within a highly conserved region of the gene, which causes an amino acid change from Ser to Arg and may encode functionally distinct proteins [23]. Although some functional studies suggest that p21-Ser and p21-Arg variant alleles present similar kinase inhibitory activity and growth suppression ability[19], they have been shown to differ significantly in their transcriptional efficiency. For example, individuals carrying the p21-Arg-encoding allele manifest a lower p21 expression[75]. Our meta-analysis supports that individuals carrying the Arg/Arg genotype have a higher cancer risk as assessed in a recessive model.

Because of the paradoxical role of p21 contributing to both cancer suppressive and promoting effects, it is biologically plausible that multiple tumors with different carcinogenic mechanisms may reflect different susceptibilities conferred by the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism. In our meta-analysis, we found that the effect of the p21 31Arg/Arg genotype was unfavorable toward the development of breast, head and neck, cervical, and colorectal cancer, but appeared to be favorable toward the development of lung, skin, gastric, and esophageal cancer. Heterogeneity analysis also showed that tumor type contributed to substantial between-study heterogeneity. Thus, inconsistent results among different cancers may involve the mechanisms by which p21 regulates cell proliferation or apoptosis in different cancer cells. However, this difference could also be due to limited statistical power as a result of a small sample size in subgroup analysis. Recently, a meta-analysis investigated the association between the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and breast cancer risk among 22 109 cases and 29 127 controls, but no significant associations were found[76], which is consistent with our results in breast cancer-including additional studies (22 656 cases and 30 133 controls). Moreover, studies have reported that estrogen stimulates cell mitotic activity and Carcinogenesis in breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer[77],[78]. In subgroup analysis, we found that the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism was significantly associated with risk toward the development of estrogen-related cancer, possibly due to different carcinogenic mechanisms of different cancer types including gene-environment interactions.

Ethnicity may affect tumor susceptibility by different genetic factors and environmental exposures through gene-gene and gene-environment interactions. In our meta-analysis, we observed that the association between the p21 31Arg/Arg genotype and overall cancer risk was significant in Caucasians but not in Asians. Furthermore, our results indicated that the association of significantly increased cancer risk with the p21 31Arg/Arg genotype was more pronounced in studies with population-based controls, matching design, or larger sample sizes. The possible explanation may be that population-based controls were more representative of the general population and that studies with matching design or larger sample sizes may eliminate some bias and thus have a greater reliability or statistical power to detect the moderate effect of this single nucleotide polymorphism, suggesting that some characteristics should be carefully considered in genetic association studies, such as the selection of controls, matching status, ethnicity information, and sample size.

Several potential limitations of the present meta-analysis warrant consideration. First, although the funnel plot and Egger's test showed no publication bias, selection bias might have occurred because only studies published in English were included in our meta-analysis. Second, in the stratification analyses, the numbers of individuals carrying the Arg/Arg genotype in some subgroups were relatively small because of its low allele frequency in Caucasian subjects, which might have a small statistical power to detect the real association. Third, our results were based on unadjusted estimates, because ORs in all studies were not adjusted by the same potential confounders, such as age, sex, and exposure. Thus, a more precise analysis should be conducted, if individual data were available, which would allow for the adjustment by some co-variants and further evaluation of potential gene-environment interactions. In summary, this meta-analysis provides statistical evidence that the p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism may contribute to individual susceptibility to cancer. Future well-designed large studies were warranted to validate our findings in different ethnic populations.

References

- 1.Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell cycle control and cancer [J] Science. 1994;266(5192):1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakoff-Nahoum S. Why cancer and inflammation? [J] Yale J Biol Med. 2006;79(3–4):123–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordon-Cardo C. Mutations of cell cycle regulators. Biological and clinical implications for human neoplasia [J] Am J Pathol. 1995;147(3):545–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLachlan TK, Sang N, Giordano A. Cyclins, Cyclin-dependent kinases and cdk inhibitors: implications in cell cycle control and cancer [J] Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 1995;5(2):127–156. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v5.i2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaumot M, Estanol JM, Casanovas O, et al. The cell cycle inhibitor p21CIP is phosphorylated by cyclin A–CDK2 complexes [J] Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241(2):434–438. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, et al. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G, Cyclin-dependent kinases [J] Cell. 1993;75(4):805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.el-Deiry WS, Harper JW, O'Connor PM, et al. WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G, arrest and apoptosis [J] Cancer Res. 1994;54(5):1169–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willenbring H, Sharma AD, Vogel A, et al. Loss of p21 permits Carcinogenesis from chronically damaged liver and kidney epithelial cells despite unchecked apoptosis [J] Cancer Cell. 2008;14(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The role of the Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in apoptosis [J] Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(8):639–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartel AL. The conflicting roles of the cdk inhibitor p21 (CIP1/WAF1) in apoptosis [J] Leuk Res. 2005;29(11):1237–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gartel AL. Is p21 an Oncogene? [J] Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(6):1385–1386. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang M, Shao ZM, Wu J, et al. p21/waf1/cip1 and mdm-2 expression in breast carcinoma patients as related to prognosis [J] Int J Cancer. 1997;74(5):529–534. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971021)74:5<529::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoji T, Tanaka F, Takata T, et al. Clinical significance of p21 expression in non-small-cell lung cancer [J] J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(18):3865–3871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang LW, Seow KM, Lee CC, et al. Decreased p21 expression in HPV-18 positive cervical carcinomas [J] Pathol Oncol Res. 2010;16(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12253-009-9191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbendary AA, Cirisano FD, Evans AC, Jr, et al. Relationship between p21 expression and mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in normal and malignant ovarian epithelial cells [J] Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(9):1571–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Waldman T, et al. Topological control of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression in normal and neoplastic tissues [J] Cancer Res. 1995;55(13):2910–2919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erber R, Klein W, Andl T, et al. Aberrant p21 (CIP1/WAF1) protein accumulation in head-and-neck cancer [J] Int J Cancer. 1997;74(4):383–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970822)74:4<383::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiohara M, el-Deiry WS, Wada M, et al. Absence of WAF1 mutations in a variety of human malignancies [J] Blood. 1994;84(11):3781–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun Y, Hildesheim A, Li H, et al. No point mutation but a codon 31ser→arg polymorphism of the WAF-1/CIP-1/p21 tumor suppressor gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC): the polymorphism distinguishes Caucasians from Chinese [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4(3):261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facher EA, Becich MJ, Deka A, et al. Association between human cancer and two polymorphisms occurring together in the p21Waf1/Cip1 Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene [J] Cancer. 1997;79(12):2424–2429. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2424::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukas J, Groshen S, Saffari B, et al. WAF1/Cip1 gene polymorphism and expression in carcinomas of the breast, ovary, and endometrium [J] Am J Pathol. 1997;150(1):167–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mousses S, Ozcelik H, Lee PD, et al. Two variants of the CIP1/WAF1 gene occur together and are associated with human cancer [J] Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(6):1089–1092. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.6.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chedid M, Michieli P, Lengel C, et al. A single nucleotide substitution at codon 31 (Ser/Arg) defines a polymorphism in a highly conserved region of the p53-inducible gene WAF1/CIP1 [J] Oncogene. 1994;9(10):3021–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goode EL, Fridley BL, Vierkant RA, et al. Candidate gene analysis using imputed genotypes: cell cycle single-nucleotide polymorphisms and ovarian cancer risk [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(3):935–944. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Driver KE, Song H, Lesueur F, et al. Association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the cell cycle genes with breast cancer in the British population [J] Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(2):333–341. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keshava C, Frye BL, Wolff MS, et al. Waf-1 (p21) and p53 polymorphisms in breast cancer [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(1):127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma H, Jin G, Hu Z, et al. Variant genotypes of CDKN1A and CDKN1B are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in Chinese women [J] Int J Cancer. 2006;119(9):2173–2178. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarasov VA, Aslanyan MM, Tsyrendorzhiyeva ES, et al. Genetically determined subdivision of human populations with respect to the risk of breast cancer in women [J] Dokl Biol Sci. 2006;406:66–69. doi: 10.1134/s0012496606010182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staalesen V, Knappskog S, Chrisanthar R, et al. The novel p21 polymorphism p21G251A is associated with locally advanced breast cancer [J] Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 pt 1):6000–6004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox A, Dunning AM, Garcia-Closas M, et al. A common coding variant in CASP8 is associated with breast cancer risk [J] Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):352–358. doi: 10.1038/ng1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MARIE-GENICA Consortium on Genetic Susceptibility for Menopausal Hormone Therapy Related Breast Cancer Risk Polymorphisms in the BRCA1 and ABCBI genes modulate menopausal hormone therapy associated breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women [J] Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120(3):727–736. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sjalander A, Birgander R, Rannug A, et al. Association between the p21 codon 31 A1 (arg) allele and lung cancer [J] Hum Hered. 1996;46(4):221–225. doi: 10.1159/000154357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shih CM, Lin PT, Wang HC, et al. Lack of evidence of association of p21WAF1/CIP1 polymorphism with lung cancer susceptibility and prognosis in Taiwan [J] Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2000.tb00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su L, Liu G, Zhou W, et al. No association between the p21 codon 31 serine-arginine polymorphism and lung cancer risk [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(2):174–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popanda O, Edler L, Waas P, et al. Elevated risk of squamous-cell carcinoma of the lung in heavy smokers carrying the variant alleles of the TP53 Arg72Pro and p21 Ser31Arg polymorphisms [J] Lung Cancer. 2007;55(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi YY, Kang HK, Choi JE, et al. Comprehensive assessment of P21 polymorphisms and lung cancer risk [J] J Hum Genet. 2008;53(1):87–95. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai MH, Chen WC, Tsai FJ. Correlation of p21 gene codon 31 polymorphism and TNF-alpha gene polymorphism with nasopharyngeal carcinoma [J] J Clin Lab Anal. 2002;16(3):146–150. doi: 10.1002/jcla.10032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodrigues FC, Kawasaki-Oyama RS, Fo JF, et al. Analysis of CDKN1A polymorphisms: markers of cancer susceptibility? [J] Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;142(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li G, Liu Z, Sturgis EM, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of p21 are associated with risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [J] Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(9):1596–1602. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bau DT, Tsai MH, Lo YL, et al. Association of p53 and p21 (CDKN1A/WAF1/CIP1) polymorphisms with oral cancer in Taiwan patients [J] Anticancer Res. 2007;27(3B):1559–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomes CC, Drummond SN, Guimaraes AL, et al. P21/WAF1 and cyclin D1 variants and oral squamous cell carcinoma [J] J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(3):151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roh J, Kim M, Kim J, et al. Polymorphisms in codon 31 of p21 and cervical cancer susceptibility in Korean women [J] Cancer Lett. 2001;165(1):59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00401-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harima Y, Sawada S, Nagata K, et al. Polymorphism of the WAF1 gene is related to susceptibility to cervical cancer in Japanese women [J] Int J Mol Med. 2001;7(3):261–264. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.7.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JE, Lee SJ, Namkoong SE, et al. Gene-gene and gene-environmental interactions of p53, p21, and IRF-1 polymorphisms in Korean women with cervix cancer [J] Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14(1):118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee SA, Kim JW, Roh JW, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTM1, p21, p53 and HPV infection with cervical cancer in Korean women [J] Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(1):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhattacharya P, Sengupta S. Lack of evidence that proline homozygosity at codon 72 of p53 and rare arginine allele at codon 31 of p21, jointly mediate cervical cancer susceptibility among Indian women [J] Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(1):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian Q, Lu W, Chen H, et al. The nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms in codon 31 of p21 gene and the susceptibility to cervical cancer in Chinese women [J] Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(6):1011–1014. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a8b950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roh JW, Kim BK, Lee CH, et al. P53 codon 72 and p21 codon 31 polymorphisms and susceptibility to cervical adenocarcinoma in Korean women [J] Oncol Res. 2010;18(9):453–459. doi: 10.3727/096504010x12671222663719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu MT, Wu DC, Hsu HK, et al. Association between p21 codon 31 polymorphism and esophageal cancer risk in a Taiwanese population [J] Cancer Lett. 2003;201(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu MT, Chen MC, Wu DC. Influences of lifestyle habits and p53 codon 72 and p21 codon 31 polymorphisms on gastric cancer risk in Taiwan [J] Cancer Lett. 2004;205(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lai KC, Chen WC, Jeng LB, et al. Association of genetic polymorphisms of MK, IL-4, p16, p21, p53 genes and human gastric cancer in Taiwan [J] Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(10):1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taghavi N, Biramijamal F, Abbaszadegan MR, et al. P21(waf1/cip1) gene polymorphisms and possible interaction with cigarette smoking in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in northeastern Iran: a preliminary study [J] Arch Iran Med. 2010;13(3):235–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang W, Qi Q, Zhang H, et al. p21 Waf1/Cip1 polymorphisms and risk of esophageal cancer [J] Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(5):1453–1458. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polakova V, Pardini B, Naccarati A, et al. Genotype and haplotype analysis of cell cycle genes in sporadic colorectal cancer in the Czech Republic [J] Hum Mutat. 2009;30(4):661–668. doi: 10.1002/humu.20931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu B, Zhang Y, Jin M, et al. Association of selected polymorphisms of CCND1, p21, and caspase8 with colorectal cancer risk [J] Mol Carcinog. 2010;49(1):75–84. doi: 10.1002/mc.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cacina C, Yaylim-Eraltan I, Arikan S, et al. Association between CDKN1A Ser31Arg and C20T gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk and prognosis [J] In Vivo. 2010;24(2):179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konishi R, Sakatani S, Kiyokane K, et al. Polymorphisms of p21 Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and malignant skin tumors [J] J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(3):177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(00)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C, Chen K, Liu Z, et al. Polymorphisms of TP53 Arg72Pro, but not p73 G4C14>A4TA4 and p21 Ser31Arg, contribute to risk of cutaneous melanoma [J] J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(6):1585–1588. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hachiya T, Kuriaki Y, Ueoka Y, et al. WAF1 genotype and endometrial cancer susceptibility [J] Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72(2):187–192. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen WC, Wu HC, Hsu CD, et al. p21 gene codon 31 polymorphism is associated with bladder cancer [J] Urol Oncol. 2002;7(2):63–66. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(01)00152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roh JW, Kim JW, Park NH, et al. p53 and p21 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to endometrial cancer [J] Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(2):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hishida A, Matsuo K, Tajima K, et al. Polymorphisms of p53 Arg72Pro, p73 G4C14-to-A4T14 at exon 2 and p21 Ser31Arg and the risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Japanese [J] Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(5):957–964. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001638878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang SP, Wu WJ, Chang WS, et al. p53 Codon 72 and p21 codon 31 polymorphisms in prostate cancer [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(12):2217–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Kikuno N, et al. MDM2 SNP309 polymorphism as risk factor for susceptibility and poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma [J] Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(14):4123–4129. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gayther SA, Song H, Ramus SJ, et al. Tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms in cell cycle control genes and susceptibility to invasive epithelial ovarian cancer [J] Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3027–3035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rajaraman P, Wang SS, Rothman N, et al. Polymorphisms in apoptosis and cell cycle control genes and risk of brain tumors in adults [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1655–1661. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chung CJ, Huang CJ, Pu YS, et al. Polymorphisms in cell cycle regulatory genes, urinary arsenic profile and urothelial carcinoma [J] Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232(2):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen J, Amos CI, Merriman KW, et al. Genetic variants of p21 and p27 and pancreatic cancer risk in non-Hispanic Whites: a case-control study [J] Pancreas. 2010;39(1):1–4. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bd51c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roninson S, Allan JM, Law GR, et al. High-throughput association testing on DNA pools to identify genetic variants that confer susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia [J] Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(5):795–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xi YG, Ding KY, Su XL, et al. p53 polymorphism and p21WAF1/CIP1 haplotype in the intestinal gastric cancer and the precancerous lesions [J] Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(11):2201–2206. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lau J, loannidis JP, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews [J] Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials [J] Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in metaanalysis detected by a simple, graphical test [J] BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xie HL, Su Q, He XS, et al. Expression of p21(WAF1) and p53 and polymorphism of p21 (WAF1) gene in gastric carcinoma [J] World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(8):1125–1131. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i8.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnson GG, Sherrington PD, Carter A, et al. A novel type of p53 pathway dysfunction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia resulting from two interacting single nucleotide polymorphisms within the p21 gene [J] Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):5210–5217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qiu LX, Zhang J, Zhu XD, et al. The p21 Ser31Arg polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis involving 51,236 subjects [J] Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124(2):475–479. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0858-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Persson I. Estrogens in the causation of breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers-evidence and hypotheses from epidemiological findings [J] J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74(5):357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song RX, Santen RJ. Apoptotic action of estrogen [J] Apoptosis. 2003;8(1):55–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1021649019025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]