ABSTRACT

We investigated the presence of Salmonella in the green anole (Anolis carolinensis), an invasive alien species on Chichi Island, Japan. Samples were also collected from feral goats and public toilets on the island to examine infectious routes. Salmonellae were isolated from 27.1% of 199 samples; 32.6% of 141 cloacal samples from anoles, 62.5% of 8 intestinal samples from anole carcasses, 16.7% of 12 fecal samples from goats and 2.6% of 38 toilet bowl swabs. The serotype of most isolates was Salmonella Oranienburg (94.4% of 54). Although we did not confirm the infection pathways, our results indicated that green anoles are a risk factor as a source of Salmonella for public health. It is important to consider endemic pathogens that may be amplified by alien species within their introduced areas.

Keywords: green anole, invasive alien species, lizard, reptiles, Salmonella Oranienburg

Recently, invasive alien species have become widespread in Japan. Their impact on ecosystems as competitors for food and habitat and as predators of endemic and endangered animals has been demonstrated [9, 25]. They also cause serious damage to agriculture resulting in countermeasures being taken to control the populations. Although these species are a potential risk for introducing infectious diseases to humans by acting as reservoirs, there are only a few proposals in Japan to control the transport and amplification of these pathogens [11] and no published studies on zoonotic pathogens carried by alien lizards.

The green anole (Anolis carolinensis) is an arboreal lizard that originally inhabited regions in North America and was then introduced to Guam [4, 6] and Hawaii [1] in the 1950s and Chichi Island in the 1960s [18, 20]. The lizards have impacted negatively on the ecosystems of Chichi Island [21]. In this study, we conducted a surveillance study focused on Salmonella, zoonotic bacteria that are isolated at a high rate from reptiles. The object of this study was to evaluate the risks of pathogenic microorganisms being carried by an alien species, namely the green anole, to gain information for public health.

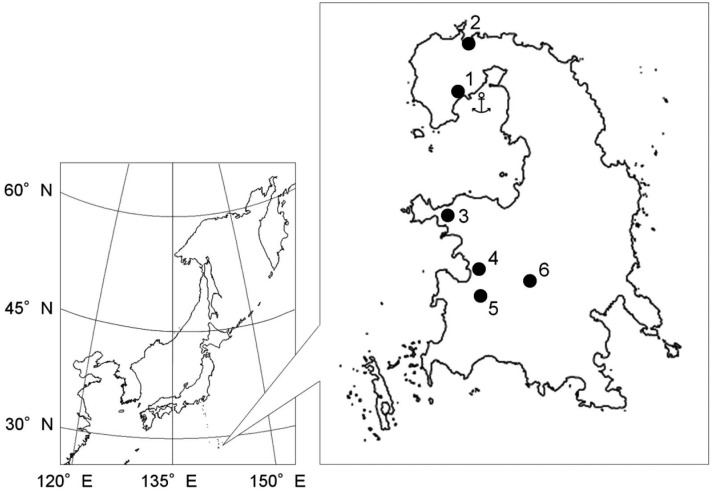

The survey was carried out on Chichi Island, located at 27°05’ N and 142°11’ E (Fig. 1

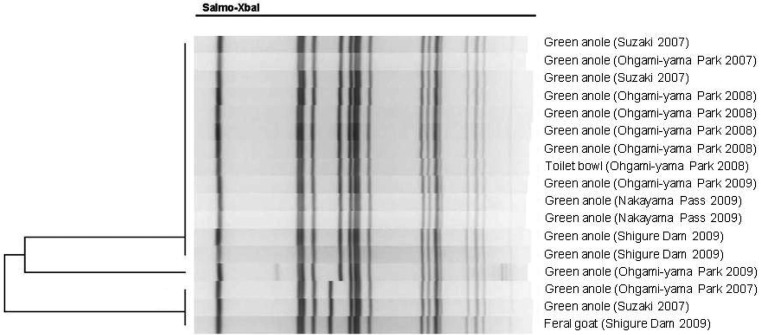

Fig. 2.

PFGE profiles of Salmonella Oranienburg from samples collected in several locations on the island. The PFGE patterns were classified into only one type.

). Samples were collected at six different places (Fig. 1). Sampling was performed with the cooperation of the Japan Wildlife Research Center, under the permission of the Ministry of the Environment, for 5 days a month during 2007 to 2009 (Table 1). Especially, the area near Ohgami-yama Park has a high population density, and the other locations have only a few inhabitants.

Fig. 1.

Location of Chichi Island with the Ogasawara archipelago and the sampling sites on the island. The numbers in the figure indicates the following site locations: 1, Ohgami-yama Park; 2, Miyano Beach; 3, Kominato; 4, Suzaki; 5, Nakayama Pass; 6, Shigure Dam. The anchor symbol indicates the location of the main port of Chichi island.

Table 1. Isolation of Salmonella in cloacal samples from green anoles to location and year of sampling.

| Samples and month/year of sampling |

% of isolation (positive samples/total samples examined) of Salmonella by area on the island | Prevalence of each year |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohgami-yama Park |

Miyano Beach |

Suzaki | Kominato Beach |

Shigure Dam |

Nakayama Pass |

Ohgami-yama Park/Suzaki* |

Unknown | ||

| Cloacal samples from green anoles | |||||||||

| October 2007 | 28 (7/25) | - | 41.7 (5/12) | - | - | - | - | - | 32.4 (12/37) |

| June 2008 | 43.8 (7/16) | - | - | - | - | - | 37.9 (11/29) | - | 40 (18/45) |

| July 2009 | 45.5 (5/11) | 15.4 (2/13) | - | - | 37.5 (6/16) | 17.6 (3/17) | - | - | 27.1 (16/59) |

| Sub total | 36.5 (19/52) | 15.4 (2/13) | 41.7 (5/12) | - | 37.5 (6/16) | 17.6 (3/17) | 37.9 (11/29) | - | 32.6 (46/141) |

| Intestinal samples from frozen green anoles | |||||||||

| October 2007 & June 2008 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 62.5 (5/8) | 62.5 (5/8) |

| Fecal samples from feral goats | |||||||||

| July 2009 | 0 (0/4) | - | - | - | 33.3 (1/3) | 20 (1/5) | - | - | 16.7 (2/12) |

| Swab samples from toilet bowls | |||||||||

| June 2008 | 10 (1/10) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 (1/10) |

| July 2009 | 0 (0/22) | 0 (0/3) | - | 0 (0/3) | - | - | - | - | 0 (0/28) |

| Sub total | 3.1 (1/32) | 0 (0/3) | - | 0 (0/3) | - | - | - | - | 2.6 (1/38) |

| Total | 22.7 (20/88) | 12.5 (2/16) | 41.7 (5/12) | 0 (0/6) | 36.8 (7/19) | 18.2 (4/22) | 37.9 (11/29) | 62.5 (5/8) | 27.1 (54/199) |

* Ohgami-yama Park/Suzaki indicates that the sampling location could not be distinguished between these two areas.

Cloacal samples were collected from 141 green anoles found in 5 locations and one unidentified location (Fig. 1 and Table 1) placed immediately in Seed Swab γ No. 1 Eiken transport medium (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and stored at 4°C until laboratory examination. Eight green anole carcasses of unknown origin preserved frozen at the Japan Wildlife Research Center were transported to our laboratory and defrosted, and the large intestine contents were collected. We also collected 38 swabs from eight public lavatories (toilet bowl) at 3 places and 12 fecal samples from feral goats (Capra hircus), the other invasive alien species on the island at 3 locations (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

All samples were examined for Salmonella spp. by transferring into 10 ml Enterobacteriacae Enrichment Mannitol Broth, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 hr. One ml aliquot of each culture was then transferred to 9 ml Rappaport–Vassiliadis broth and incubated at 42°C for 20 hr. And then, these samples were cultured on Salmonella–Shigella agar with colonies screened for Salmonella using triple sugar iron and lysine indole motile media, followed by identification using the ID-Test·EB-20 system (Nissui Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Serotyping was carried out according to the Kauffmann and White scheme (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). PFGE was performed using S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 as the standard [8] with 17 samples included in the analysis according to year, location and source of sampling ( Fig. 2 and Table 1). The resulting profiles were interpreted by visual analysis, and profile photographs were then scanned and analyzed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Similarities were determined using the Dice coefficient with clustering based on the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages and a band position tolerance of 1.2% [19]. Statistical analysis was performed using χ2 tests for independence which were used to evaluate differences in Salmonella prevalence in cloacal samples collected in different years and places using JMP 9.0 (SAS Institute, Tokyo, Japan). To assess differences in prevalence between the sampling locations, we omitted 29 cloacal samples collected in 2008 as the location of these samples could not be confirmed.

Table 2. Serotypes of Salmonella isolated from samples grouped according to area.

| Serotype (% of 54 isolates) and isolated samples |

Place and number of each Salmonella serotype isolated | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohgami-yama Park |

Miyano Beach |

Suzaki | Nakayama Pass |

Shigure Dam |

Ohgami-yama Park/Suzaki |

unknown | ||

| S. Oranienburg (94.4) | ||||||||

| Cloacal sample from green anole | 18 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 11 | - | 44 |

| Intestinal sample from green anole | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 5 |

| Fecal sample from feral goat | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | |||

| swab sample from toilet bowl | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| S. Weltevreden (1.9) | ||||||||

| Cloacal sample from green anole | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| S. Adelaide (3.7) | ||||||||

| Cloacal sample from green anole | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Fecal sample from feral goat | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

Salmonella spp. were isolated from 27.1% of the 199 samples collected from green anoles, feral goats and toilets; the overall isolation rate from 141 cloacal samples was 32.6%. The specific rates divided by area are shown in Table 1. Of the eight intestinal contents, 5 were positive for Salmonella. The isolation rates of the 12 fecal samples from feral goats and 38 swabs from toilet bowls were 16.7% and 2.6%, respectively. The specific rates for these samples divided by area are shown in Table 1.

There were no significant differences in Salmonella prevalence between the 3 sampling years (χ2=1.928, P=0.381, df=2) or between the lizard cloacal samples (χ2=3.788, P=0.285, df=3), goat fecal samples (χ2=1.440, P=0.487, df=2) or toilet bowl swabs (χ2=0.193, P=0.908, df=2).

The Salmonella Oranienburg serotype was isolated from 94.4% of 54 isolates (44 lizard cloacal samples and 1 goat fecal sample). The S. Weltevreden and S. Adelaide serotypes were also isolated from 1.9% and 3.7% of the 54 isolates, respectively. Table 2 shows the number and serotype-specific location of each isolate. Figure 2 shows the PFGE profiles of S. Oranienburg were classified into one type (more than 92.3% similarity).

The number of human cases of Salmonella infection associated with pet reptiles is increasing in the United States and Europe. Approximately 6% of human cases of Salmonella infection reported annually in the United States are attributed to exposure to reptiles, amphibians [15] or pet lizards [2]. There is also a report of a Japanese patient with Salmonellosis caused due to exposure to a pet green iguana (Iguana iguana) [10]. The reported Salmonella prevalence in various pet lizards in Japan is 17.3% in 98 green iguanas [13], 62.7% in 158 lizards [7] and 66.1% in 71 lizards of 16 species [17]. In contrast, the prevalence in wild lizards in Japan was shown to be only 4.1% in 434 individuals [7]. The relatively high Salmonella prevalence observed in green anoles on Chichi Island is comparable to these earlier studies, indicating that these lizards could become a reservoir and play an important role in the epidemiology of the pathogen. This is the first report of Salmonella infestation in alien lizards in Japan.

The population density of green anoles on Chichi Island is high (600–2,570 heads/10,000 m2 [18]) with the lizards roaming freely in and around houses, making it necessary for the community to prevent fecal pollution by the lizards and avoid contact. As many tourists visit the Ogasawara Islands annually [22], it is also necessary to introduce formal precautions against contracting Salmonella infection from the lizards.

In this study, we detected three serotypes of Salmonella. S. Oranienburg has been identified as the causative agent of food poisoning in humans [24] with a large-scale outbreak of the organism in main land of Japan in 1999 that affected 1634 people [16]. However, S. Oranienburg is an uncommon serovar in food poisoning cases in Japan, except on Okinawa Island, the southern part of Japan, and occasionally elsewhere [14]. S. Weltevreden and S. Adelaide are also uncommon Salmonella serotypes in Japan and often geographically restricted [14]. Salmonella gastroenteritis has occurred sporadically in Chichi Island since 2000, though the source of these infections remains unclear. A study on 32 patients from this area showed that related isolates were S. Oranienburg (90.6%), S. Gaminara (6.3%) and S. Weltevreden (3.1%) [12] with feral goats suspected as the source of infection. As the PFGE patterns indicated that detected S. Oranienburg in this study from green anoles, a toilet bowl swab and feral goat feces has the same source of infection and transmission [19], however, this S. Oranienburg strain was different from that in the 1999 food poisoning incident in Japan, this excludes the possibility that these isolates originated from human carriers [22].

We also found S. Oranienburg infections in feral goats from the island. These goats became feral in the 1940s before the introduction of green anoles [12]. As the habitats of the 2 species overlap, we suspect that there is transmission of Salmonella from goats to green anoles and vice versa. Fecal matter may also contribute to soil contamination with Salmonella, making transmission from feral goats to green anoles more likely. To our knowledge, there is no record of S. Oranienburg being isolated from green anoles with Salmonella subspecies isolated from wild lizards in Japan mainly being type IV (72.2%), followed by type I (27.8%) [7]. It is therefore difficult to determine whether the lizards were infected with Salmonella on the island or were already infected prior to invading the area.

Previous reports have suggested that introducing alien species poses risks and may negatively impact the health of humans, domestic animals and endemic species [5, 23]. It is therefore important to consider that alien species may be novel carriers or reservoirs for pathogens in areas in which they are introduced. Although our study did not determine the infection route, we consider that Salmonella is transmitted to green anoles by natural reservoirs, such as feral goats (spill-over) and that the lizards spread the pathogen throughout the island (spill-back) [3]. During surveys and control of alien species, it is necessary to recognize that alien pathogens will invade along with host species and that endemic pathogens may be acquired or amplified by the alien species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masaaki Takiguci and Yuji Takafuji of the Japan Wildlife Research Center for helping capture and sample the green anoles, Ikuno Hayashida, Yuri Endo, Emi Sasaki and Akiko Mitsuhashi of Nihon University and Azabu University for helping capture the green anoles and bacterial culture and Masafumi Nukina of Kobe Municipal Environmental Hygiene Research Center for helping salmonella serotyping. This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for challenging Exploratory Research (24651270), a Nihon University Research Grant, Academic Frontier Project “Surveillance and control for zoonoses,” and the “High-Tech Research Center” Project for Private University from MEXT of Japan for KM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beletsky L.2000. p. 416. Hawaii The Ecotravellers Wildlife Guide. Academic Press, London. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooke F. J., De Pinna E., Maguire C., Guha S., Pickard D. J., Farrington M., Threlfall E. J.2009. First report of human infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Apapa resulting from exposure to a pet lizard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47: 2672–2674. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02475-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daszak P., Cunningham A. A., Hyatt A. D.2000. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife-Threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287: 443–449. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fritts T., Rodda G.1998. The role of introduced species in the degradation island ecosystems: A case history of Guam. Annu. Rev. of Ecol. Syst. 29: 113–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg S. R., Bursey C. R.2000. Transport of helminths to Hawaii via the brown anole, Anolis sagrei (Polychrotidae). J. Parasitol. 86: 750–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddock R. L., Nocon F. A., Santos E. A., Taylor T. G.1990. Reservoirs and vehicles of Salmonella infection on Guam. Environ. Int. 16: 11–16. doi: 10.1016/0160-4120(90)90199-G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashidani H., Iwata Nakadai A.2008. Salmonella in reptiles. Modern Media 54: 165–170 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter S. B., Vauterin P., Lambert-Fair M. A., Van Duyne M. S., Kubota K., Graves L., Wrigley D., Barrett T., Ribot E.2005. Establishment of a universal size standard strain for use with the PulseNet standardized pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols: converting the national databases to the new size standard. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43: 1045–1050. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1045-1050.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda T., Asano M., Matoba Y., Abe G.2004. Present status of invasive alien raccoon and its impact in Japan. Glob. Environ. Res. 8: 125–131 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Infectious A. S. R.2010. http://idsc.nih.go.jp/iasr/26/310/kj3102.html Accessed December 2010 (in Japanese).

- 11.Inoue K., Kabeya H., Fujita H., Makino T., Asano M., Inoue S., Inokuma H., Nogami S., Maruyama S.2011. Serological survey of five zoonoses, Scrub typhus, Japanese spotted fever, Tularemia, Lyme Disease, and Q Fever, in feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Japan. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 11: 15–19. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue S., Saikawa N., Nakagawa S., Shinomiya M.2006. Fecal examination of feral goats on Ogasawara Islands. pp. 194–195. In: Proceedings of the Society of Public Health, Social Welfare and Medical Services, Tokyo Metropolitan Government 2006 (in Japanese).

- 13.Kabeya H., Fujita M., Morita Y., Yokoyama E., Yoda K., Yamauchi A., Murata K., Maruyama S.2008. Salmonella, Pasteurella and Staphylococcus infection in pet iguanas. J. Jpn. Vet. Med. Assoc. 61: 70–74 (in Japanese with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudaka J., Itokazu K., Taira K., Iwai A., Kondo M., Susa T., Iwanaga M.2006. Characterization of Salmonella isolated in Okinawa, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 59: 15–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mermin J., Hutwagner L., Vugia D., Shallow S., Daily P., Bender J., Koehler J., Marcus R., Angulo F. J.,Emerging Infections Program FoodNet Working Group. 2004. Reptiles, amphibians, and human Salmonella infection: a population-based, case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38: S253–261. doi: 10.1086/381594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyakawa S., Takahashi K., Hattori M., Itoh K., Kurazono T., Amano F.2006. Outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg infection in Japan. J. Environ. Biol. 27: 157–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakadai A., Kuroki T., Kato Y., Suzuki R., Yamai S., Yaginuma C., Shiotani R., Yamanouchi A., Hayashidani H.2005. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in pet reptiles in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 67: 97–101. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okochi I., Yoshimura M., Abe T., Suzuki H.2010. High population densities of an exotic lizard, Anolis carolinensis and its possible role as a pollinator in the Ogasawara Islands. pp. 71–74. In: Restoring the Oceanic Island Ecosystem: Impact and Management of Invasive Alien Species in the Bonin Islands (Kawakami, K. and Okochi, I. eds.), Springer, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover F. C., Arbeit R. D., Goering R. V., Mickelsen P. A., Murray B. E., Persing D. H., Swaminathan B.1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33: 2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) of the IUCN Species Survival Commission2010. interface.creative.auckland.ac.nz/database/welcome Accessed December 2010.

- 21.Toda M., Takahashi H., Nakagawa N., Sukigara N.2010. Ecology and control of the green anole (Anolis carolinensis), an invasive alien species on the Ogasawara Islands. pp. 145–152. In: Restoring the Oceanic Island Ecosystem: Impact and Management of Invasive Alien Species in the Bonin Islands (Kawakami, K. and Okochi, I. eds.), Springer, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokyo Metropolitan Government2010. www.metro.tokyo.jp/INET/BOSHU/2009/09/22j9h300.htm Accessed December 2010 (in Japanese).

- 23.Rushton S. P., Lurz P. W., Gurnell J., Nettleton P., Bruemmer C., Shirley M. D., Sainsbury A. W.2006. Disease threats posed by alien species: the role of a poxvirus in the decline of the native red squirrel in Britain. Epidemiol. Infect. 134: 521–533. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805005303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werber D., Dreesman J., Feil F., Van T. U., Fell G., Ethelberg S., Hauri A. M., Roggentin P., Prager R., Fisher I. S., Behnke S. C., Bartelt E., Weise E., Ellis A., Siitonen A., Andersson Y., Tschape H., Kramer M. H., Ammon A.2005. International outbreak of Salmonella Oranienburg due to German chocolate. BMC. Infect. Dis. 5: 7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada F., Sugimura K.2004. Negative impact of an invasive small Indian mongoose Herpestes javanicus on native wildlife species and evaluation of a control project in Amami-Ohshima and Okinawa Islands, Japan. Glob. Environ. Res. 8: 117–124 [Google Scholar]