A 54-year-old white man with a BMI of 29 presented with a 6-month history of supine positional snoring and progressive orthopnea without antecedent illness, trauma, or venous thromboembolism. He required daytime oxygen therapy at 3 L/minute and was unable to tolerate laying supine due to severe orthopnea. He slept in a recliner. Epworth score was 5. Chest examination demonstrated limited diaphragmatic excursions, bilaterally absent breath sounds, and dullness to percussion over the lower chest. Upon recumbency, he became tachypneic and had abdominal paradox with accessory muscle activation.

Daytime arterial blood gases showed pH 7.33, PCO2 59, PO2 68, HCO3 30 on 2 L/min supplemental oxygen with A-a gradient of 58 mm Hg. Portable overnight oximetry done with supplemental oxygen of 2 L/min demonstrated sustained hypoxemia with minimal oscillatory desaturations. He had an oxyhemoglobin desaturation index of 3/h over a valid recording time of 6 hours. A total of 20% of time (80 min) was spent below 88%. Pulmonary function tests in sitting position revealed a TLC of 4.52 L (71% of predicted), VC of 2.03 L (46% of predicted), FEV1 of 1.47 L (42% of predicted), and a FEV1/FVC of 70%. DLCO was mildly reduced. He could not perform MIP and MEP part of the test.

QUESTION:

Which of the following is the most likely cause of this patient's orthopnea?

Congestive heart failure

Pulmonary fibrosis

Bilateral diaphragmatic weakness

Bulbar weakness

ANSWER: C. Bilateral diaphragmatic weakness.

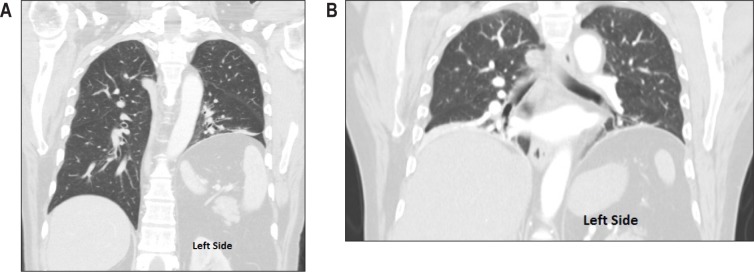

CT scan (Figures 1, 2) and diaphragmatic fluoroscopy confirmed bilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction and elevation. CT scan of the lung showed normal parenchyma with bilateral basal atelectasis without evidence of fibrotic changes. There was no mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Partial improvement in response to supplemental oxygen was suggestive of hypoxia secondary to VQ mismatch compounded by possible shunting due to bibasilar atelectasis.

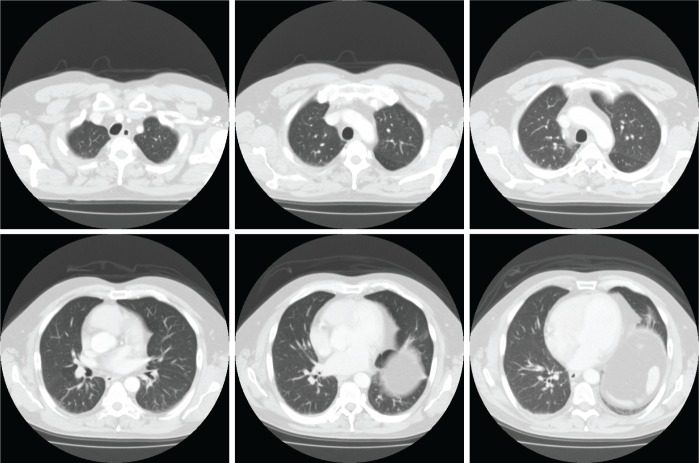

Figure 1. Coronal CT scan images of the chest.

(A) Initial scan shows left-sided unilateral hemidiaphragm elevation. (B) Scan of the chest 3 months later reveals elevation of right hemidiaphragm in addition to an already elevated left hemidiaphragm suggestive of progression of unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis to a bilateral paralysis. Also noted was bibasilar atelectasis.

Figure 2. Cross-sectional views showing no evidence of parenchymal lung disease.

EMG showed absent bilateral phrenic nerve conductions and right hemidiaphragmatic fibrillation potentials, but normal conduction and needle examination in the right upper extremity. Brachial plexus MRI was negative. Diagnostic polysomnogram was not performed, as he qualified for a bilevel PAP device based on his neuromuscular disease. Polysomnographic titration of bilevel PAP in timed mode began with an IPAP of 8 cm water and an EPAP of 4 cm water. With an IPAP of 14 cm and an EPAP of 7 cm in timed mode set at 12 breaths per minute, the patient needed blended oxygen at 2.5 L/minute to normalize oxyhemoglobin saturation. He was unable to tolerate higher pressures. During titration, he had higher respiratory events during stage REM sleep and needed higher pressures than during NREM sleep. Thirty-one months later, given persistent orthopnea and bilevel PAP requirement for sleep, he is being considered for bilateral diaphragmatic plication. He continues to be dependent on supplemental oxygen.

DISCUSSION

The prominent orthopnea and abdominal paradoxical breathing were highly suggestive signs of bilateral diaphragmatic weakness.1,2 The differential diagnoses for this patient's subacutely evolving bilateral diaphragmatic weakness included bilateral isolated phrenic neuropathy (BIPN),3–4 neuralgic amyotrophy ([NA] also known as Parsonage-Turner Syndrome),5–7 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. There was no evidence for other conditions which may rarely cause bilateral phrenic neuropathies, such as diabetes,8 multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block,9 POEMS syndrome,10 sarcoidosis,11 arsenic poisoning,12 prior irradiation,13 or acid maltase deficiency.14 BIPN presents as a painless paralysis of the diaphragm with relatively acute onset, and without antecedent factors such as infection or prior surgery.2–4 NA is a distinct and painful brachial plexus neuropathy causing patchy, multifocal paresis and sensory loss in one or both arms, with rare involvement of the phrenic nerves.5–7 A NA variant known as familial brachial plexus neuritis (hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy [HNA]) may lead to recurrent episodes of pain, numbness, and weakness in one or both upper extremities, with episodes triggered by extreme upper extremity movements or postures, infections, immunizations, or stress. HNA has been genetically linked to chromosome 17q25, where mutations may occur in the septin-9 (SEPT9) gene.15 Prognosis for recovery of normal function in affected limbs is generally favorable in NA, although in some cases persisting weakness may occur, and recurrent episodes may cause residual deficits.5–7,15–17

Our patient was diagnosed with BIPN due to painless onset, subacutely evolving symmetrical diaphragmatic weakness, and absence of other upper limb symptoms or electromyographic denervation to suggest the alternative diagnosis of NA. His symptoms did not improve over time, making the diagnosis of idiopathic bilateral phrenic nerve paralysis much more likely than neuralgic amyotrophy. Long-term persistent deficit is also more consistent with BIPN.2,3 Diaphragmatic weakness in BIPN is most often persistent, requiring lifelong noninvasive ventilatory support. However, successful relief of orthopnea and dyspnea symptoms in BIPN patients by surgical diaphragmatic plication has been reported.18 An association between upper airway collapsibility and diaphragmatic strength has been reported,19 which may be a plausible reason for new-onset snoring in our patient.

SLEEP MEDICINE PEARLS

Bilateral isolated phrenic neuropathy (BIPN) should be considered in patients presenting with orthopnea and sleep-related hypoxia.

BIPN patients experiencing significant orthopnea may be treated successfully with noninvasive positive pressure ventilatory therapy.

Unfortunately, diaphragmatic weakness may be permanent in patients with BIPN.

Orthopnea can be a symptom associated with diaphragmatic weakness, especially when associated with paradoxical abdominal movement.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Dr. St. Louis was the principal investigator.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EMG

electromyograph

- PAP

positive airway pressure

- BIPN

bilateral isolated phrenic neuropathy

- NA

neuralgic amyotrophy

- POEMS

polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, edema, M-protein, and skin abnormalities

CITATION

Jinnur P, Kumar N, Vassallo R, St Louis EK. A 54-year-old man with acute onset orthopnea and sleep-related hypoxia. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(5):595-598.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, McNamara S, Gandevia S, Halmagyi GM. Paradoxical abdominal wall movement in bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Pract Neurol. 2012;12:184–6. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2011-000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar N, Folger WN, Bolton CF. Dyspnea as the predominant manifestation of bilateral phrenic neuropathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1563–5. doi: 10.4065/79.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin PT, Andersson PB, Distad BJ, et al. Bilateral isolated phrenic neuropathy causing painless bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Neurology. 2005;65:1499–501. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183150.97425.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valls-Sole J, Solans M. Idiopathic bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:619–23. doi: 10.1002/mus.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh NE, Dumitru D, Kalantri A, Roman AM., Jr Brachial neuritis involving the bilateral phrenic nerves. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahrmann H, Grisold W, Authier FJ, Zifko UA. Neuralgic amyotrophy with phrenic nerve involvement. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:437–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<437::aid-mus2>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulvey DA, Aquilina RJ, Elliott MW, Moxham J, Green M. Diaphragmatic dysfunction in neuralgic amyotrophy: an electrophysiologic evaluation of 16 patients presenting with dyspnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:66–71. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang EW, Jardine DL, Rodins K, Evans J. Respiratory failure secondary to diabetic neuropathy affecting the phrenic nerve. Diabet Med. 2003;20:599–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyriakides T, Papacostas S, Papanicolaou E, Bagdades E, Papathanasiou ES. Sleep hypoventilation syndrome and respiratory failure due to multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:610–4. doi: 10.1002/mus.21994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokhlesi B, Jain M. Pulmonary manifestations of POEMS syndrome: case report and literature review. Chest. 1999;115:1740–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.6.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson LR, Brownsberger R, Raghu G. Respiratory failure and hypoventilation secondary to neurosarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1316–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9704068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal SK, Haldar N, Dhand UK, Chopra JS. Phrenic neuropathy in arsenic poisoning. Chest. 1991;100:878–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.3.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avila EK, Goenka A, Fontenla S. Bilateral phrenic nerve dysfunction: a late complication of mantle radiation. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:393–5. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellies U, Ragette R, Schwake C, Baethmann M, Voit T, Teschler H. Sleep-disordered breathing and respiratory failure in acid maltase deficiency. Neurology. 2001;57:1290–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Alfen N. Clinical and pathophysiological concepts of neuralgic amyotrophy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:315–22. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsairis P, Dyck PJ, Mulder DW. Natural history of brachial plexus neuropathy: report on 99 patients. Arch Neurol. 1972;27:109–117. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1972.00490140013004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes PD, Polkey MI, Moxham J, Green M. Long-term recovery of diaphragm strength in neuralgic amyotrophy. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:379–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13237999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Versteegh MI, Braun J, Voigt PG, et al. Diaphragm plication in adult patients with diaphragm paralysis leads to long-term improvement of pulmonary function and level of dyspnea. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillman DR, Walsh JH, Maddison KJ, Platt PR, Schwartz AR, Eastwood PR. The effect of diaphragm contraction on upper airway collapsibility. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115:337–45. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01199.2012. (1985) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]