Abstract

Viruses such as lentiviruses that are responsible for long lasting infections have to evade several levels of cellular immune mechanisms to persist and efficiently disseminate in the host. Over the past decades, much evidence has emerged regarding the major role of accessory proteins of primate lentiviruses, human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus, in viral evasion from the host immune defense. This short review will provide an overview of the mechanism whereby the accessory protein Vpu contributes to this escape. Vpu is a multifunctional protein that was shown to contribute to viral egress by down-regulating several mediators of the immune system such as CD4, CD1d, NTB-A and the restriction factor BST2. The mechanisms underlying its activity are not fully characterized but rely on its ability to interfere with the host machinery regulating protein turnover and vesicular trafficking. This review will focus on our current understanding of the mechanisms whereby Vpu down-regulates CD4 and BST2 expression levels to favor viral egress.

Keywords: Vpu, CD4, BST2/Tetherin, HIV-1, ESCRT, degradation, cell surface down-regulation, NF-κB

INTRODUCTION

Viral egress and replication rely on a complex interplay between viral and cellular proteins. During their replication cycle, viruses, notably lentiviruses, have to face several levels of the host immune defense mechanisms and must counteract these barriers to persist and disseminate in the host. Understanding the mechanisms underlying lentiviruses evasion from host antiviral activities has been the focus of many studies of the past decades. Not only did they contribute to major advances in the characterization of host strategies to repress viral replication, notably by the identification of antiviral cellular proteins such as APOBEC3G, SAMHD1, TRIM5α, and BST2 referred to as restriction factors (Sheehy et al., 2002; Stremlau et al., 2004; Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008; Laguette et al., 2011), but also they unraveled the importance of the accessory proteins of viruses in this process (Malim and Bieniasz, 2012).

The genome of lentiviruses encodes for several accessory proteins such as Nef, Vif, Vpr, Vpx, and Vpu, in addition to the structural and enzymatic proteins Gag, Pol, and Env and the regulatory proteins Tat and Rev (Malim and Bieniasz, 2012). These accessory proteins are, however, not common to all lentiviruses: Nef and Vpr are specific of primate lentiviruses (HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV), Vpx is expressed by HIV-2 and its closely related SIVsmm and SIVmac, Vpu is expressed by HIV-1 strains and a few strains of SIV (described later; Malim and Emerman, 2008). These proteins are not strictly required for viral replication in vitro. However, much evidence has highlighted their importance in the pathogenesis of the infection, as they contribute to modify the cell environment to facilitate viral replication and evasion from the host antiviral immune response (Malim and Emerman, 2008).

This review will provide an overview of our current understanding of the mechanisms whereby the accessory protein Vpu exploits the host cell machineries to counteract two components of the adaptive and innate host immune system: the protein CD4 and the restriction factor BST2.

CHARACTERISTICS AND FUNCTIONS OF THE ACCESSORY PROTEIN VPU

The accessory protein Vpu is an 81-amino acid type I integral membrane phosphoprotein, expressed by the genome of HIV-1, the related SIVcpz (Strebel et al., 1988) and the SIVgsn lineages including the greater spot-nosed monkey (SIVgsn), the mona monkey (SIVmon), the mustached monkey (SIVmus) and Dent’s mona monkey (SIVden) isolates (Gao et al., 1999; Courgnaud et al., 2002, 2003; Bailes et al., 2003). Vpu contains a short luminal N-terminal domain, a 23-amino acid transmembrane domain and a large cytoplasmic C-terminal domain (Strebel et al., 1988; Maldarelli et al., 1993). Vpu localizes mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the trans–Golgi network (TGN) and endosomal compartments. Two major functions have been attributed to Vpu during HIV-1 replication cycle. Firstly, Vpu targets the newly synthesized CD4 receptor for proteasomal degradation (Willey et al., 1992a). Secondly, it favors the release of viral particles from most human cell types through counteracting the inhibitory effect of BST2 (Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008). More recently, Vpu was shown to down-regulate cell surface expression of two additional mediators of the immune response: the lipid-antigen presenting protein CD1d expressed by antigen-presenting cells (Moll et al., 2010) and the natural killer cells ligand NTB-A (Shah et al., 2010). Vpu appears therefore as a key factor for HIV evasion from the host immune system.

VPU-INDUCED DOWN-REGULATION OF CD4

CD4 constitutes the major component of the receptor complex used by primate lentiviruses to infect the cells. It is a 54 kDa type I integral glycoprotein expressed at the surface of helper T-lymphocytes, cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage and hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Infection of CD4+ cells by primate lentiviruses results in a rapid and constant down-modulation of cell surface CD4 expression level (Ray and Doms, 2006). CD4 down-regulation was proposed to prevent lethal superinfection of cells by additional virions (Wildum et al., 2006), contribute to the escape of infected cells from the immune system and favor viral fitness (Willey et al., 1992b). CD4 depletion in infected cells is achieved by the concerted, though mechanistically distinct, action of three viral proteins: Nef, Vpu and, to a lower extent, Env (Wildum et al., 2006). Nef, produced shortly after infection, enhances internalization of pre-existing CD4 from the cell surface and targets the receptor for lysosomal degradation (Chaudhuri et al., 2007). Env precursor gp160 binds CD4 in the ER and blocks its transport to the cell surface (Crise et al., 1990; Jabbar and Nayak, 1990). Vpu targets CD4 molecules present in the ER for proteasomal degradation (Willey et al., 1992a).

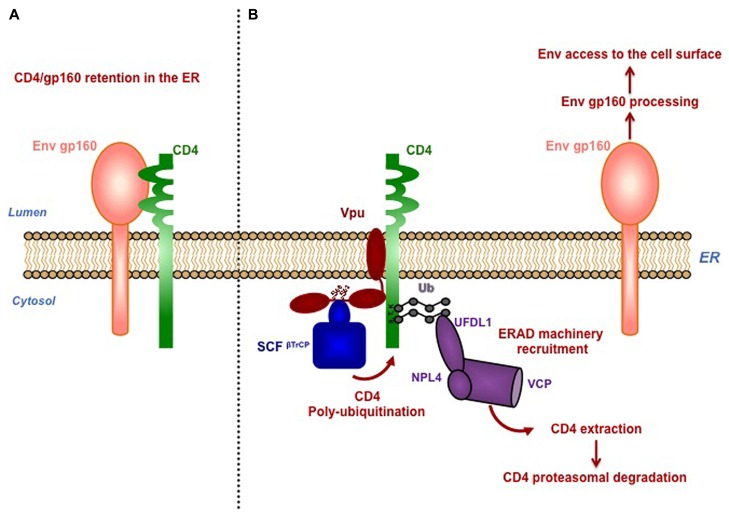

Vpu induces degradation of newly synthesized CD4 by a multi-step process involving binding of Vpu with CD4 via their transmembrane domains (TMD), retention and poly-ubiquitination of CD4 in the ER, followed by its delivery to the ER-associated degradation pathway (ERAD) for further proteasomal degradation (Magadan et al., 2010; Magadan and Bonifacino, 2012; Figure 1). Vpu-induced degradation of CD4 requires the integrity of two phosphoserines S52/S56 present in a canonical DSGXXS motif within the cytoplasmic tail of Vpu and involved in an interaction with the β-transducin repeat-containing protein 1 or 2 (β-TrCP1; β-TrCP2), two adaptors for the SKP1-cullin1-F-Box (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Margottin et al., 1998). Recruitment of the SCFβ-TrCP) complex by Vpu results in poly-ubiquitination of the cytoplasmic tail of CD4 on lysine, serine and threonine residues (Magadan et al., 2010). Interestingly, Vpu-induced SCF-mediated poly-ubiquitination of CD4 contributes to retain the receptor in the ER and enables the recruitment of the ERAD VCP-UFD1L-NPL4 dislocase complex, leading to the extraction of CD4 from the ER membrane and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome (Magadan et al., 2010; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Vpu mediates proteasomal degradation of CD4 to favor viral fitness. (A) Newly synthetized CD4 and HIV-1 envelope precursor gp160 interact in the ER through their luminal domain, preventing Env trafficking to the cell surface. (B) Vpu induces retention of CD4 in the ER through interaction via their transmembrane region and connects CD4 to SKP1-cullin1-F-Box (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase through binding with the SCF subunits β-TrCP1 and β-TrCP2. Interaction of Vpu with β-TrCP involves the conserved phophorylated serines S52 and S56, located in the cytoplasmic tail of Vpu. Recruitment of the SCFβ-TrCP complex by Vpu induces poly-ubiquitination of CD4 on lysine, serine and threonine residues in its cytoplasmic tail. Poly-ubiquitination of CD4 partially contributes its retention in the ER, through a yet-to-be-determined mechanism. Vpu-induced SCF-mediated poly-ubiquitination of CD4 enables the recruitment of the ERAD VCP-UFD1L-NPL4 dislocase complex, leading to the extraction of CD4 from the ER membrane and its subsequent degradation by the proteasome. Degradation of CD4 by Vpu was proposed to dissociate CD4 from newly synthesized viral Env present in the ER, allowing Env maturation and trafficking to the cell surface for its subsequent incorporation in the forming virions.

VPU-MEDIATED ANTAGONISM OF THE RESTRICTION FACTOR BST2

A major breakthrough in understanding how Vpu promotes the release of HIV-1 particles was made by the identification of BST2 as a restriction factor for HIV-1 release (Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008).

CHARACTERISTICS OF BST2

BST2 is a 30–36 kDa highly glycosylated type II integral membrane protein, constitutively expressed in several cell types and can be up-regulated by type-I interferon and pro-inflammatory stimuli (Neil, 2013). BST2 is composed of a short N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, linked to a transmembrane domain and an extracellular domain anchored to the membrane through a C-terminal glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) moiety (Kupzig et al., 2003). Recently, a short isoform of BST2 produced by an alternative translation initiation from the methionine residue at position 13 has been identified (Cocka and Bates, 2012). BST2 is localized at the plasma membrane (PM) in cholesterol–rich microdomains (rafts) and in intracellular compartments such as the TGN as well as early and recycling endosomes (Kupzig et al., 2003; Masuyama et al., 2009). BST2 was proposed to assemble as a “picket fence” around the lipid rafts, playing a role in organizing membrane microdomains (Billcliff et al., 2013). BST2 was shown to physically trap the de novo formed mature viral particles at the surface of infected cells, thereby considerably reducing virus release (Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008; Perez-Caballero et al., 2009; Hammonds et al., 2010). This activity relies on BST2 ability to form parallel disulfide–bond homo-dimers and to bridge virions and cellular membranes via its N– and C–terminal membrane anchoring domains (Iwabu et al., 2009; Perez-Caballero et al., 2009; Schubert et al., 2010), with a preference for an “axial” configuration in which the GPI anchors are inserted into virions, and the N-termini transmembrane anchors remain in the infected cells membrane (Venkatesh and Bieniasz, 2013).

Although initially identified as the factor responsible for defective release of HIV-1 mutants lacking the accessory gene vpu (Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008), it is now well established that BST2 restricts the release of nearly all enveloped viruses (retroviruses, herpes viruses, filoviruses, rhabdoviruses, paramyxoviruses, and arenaviruses) (Neil, 2013). BST2 therefore appears as a major mediator of the innate immune defense against viral dissemination. Primates lentiviruses deploy three proteins to antagonize BST2 antiviral activity: Vpu in HIV-1 (Neil et al., 2008; Van Damme et al., 2008); Env in HIV-2 ROD10, HIV-2 RODA, SIVagmTan and SIVmac239Δnef isolates (Gupta et al., 2009b; Le Tortorec and Neil, 2009; Hauser et al., 2010; Serra-Moreno et al., 2011) and Nef in most isolates of SIV (Jia et al., 2009; Sauter et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009). HIV-1 Vpu, HIV-2 Env, and SIV Nef were shown to down-regulate the cell surface expression level of BST2 to favor its removal from viral budding sites and further viral release (Neil, 2013). To date, the precise mechanism involved in this process has not been fully characterized.

BINDING OF VPU WITH BST2

Binding of Vpu with BST2 through their respective TMD was shown to be essential to counteract BST2 antiviral activity. Mutagenesis analyzes have unraveled the critical role of residues I34, L37, L41 of BST2 and A14, W22 and to some extent A18 of Vpu in this interaction (Vigan and Neil, 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2011). These residues were proposed to form an anti-parallel helix-helix interface (Skasko et al., 2012). Interestingly, recent studies have identified additional residues, located at the periphery of the TMD of BST2 and Vpu respectively, required for the interaction between both proteins and antagonism of BST2 (McNatt et al., 2013; Pickering et al., 2014).

VPU-INDUCED CELL SURFACE DOWN-REGULATION OF BST2

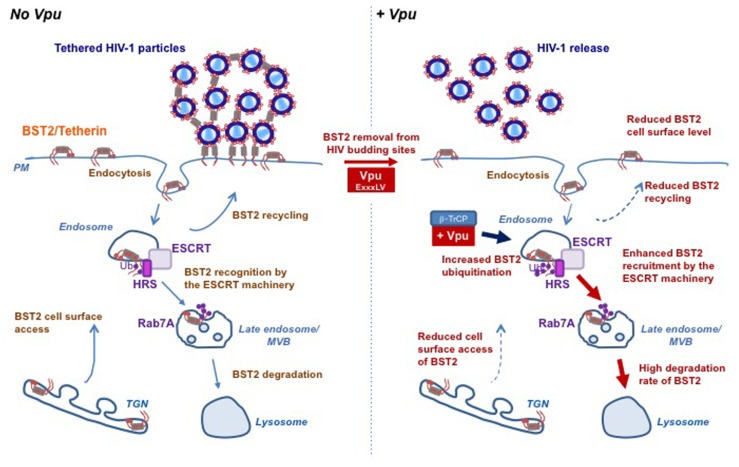

The mechanism whereby Vpu decreases cell surface BST2 expression appears to rely on interference with BST2 intracellular trafficking. BST2 was thought to cycle between the PM, the TGN and the endosomes, with a fraction sorted for lysosomal degradation through an Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport (ESCRT)-mediated pathway (Rollason et al., 2007; Masuyama et al., 2009; Habermann et al., 2010; Janvier et al., 2011). Internalization of BST2 from the PM occurs through clathrin-coated vesicles, via direct binding of the clathrin adaptor complexes AP2 with non-canonical dual tyrosine residues (Y6XY8) in the cytoplasmic tail of BST2 (Rollason et al., 2007; Masuyama et al., 2009). Binding of BST2 with AP1 complexes regulates its retrieval from the early endosomes back to the TGN (Rollason et al., 2007). Vpu does not increase the rate of BST2 endocytosis but rather slows down the recycling of internalized BST2 back to the PM and inhibits the access of de novo synthetized BST2 to the cell surface, thereby decreasing the resupply of BST2 to the PM (Mitchell et al., 2009; Dube et al., 2011; Lau et al., 2011; Schmidt et al., 2011; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Vpu subverts the host cell trafficking and ubiquitin machineries to counteract BST2 antiviral activity. BST2 physically tethers HIV-1 particles on the surface of infected cells preventing their release and further dissemination. The accessory protein Vpu counteracts this restriction by hijacking the host machineries involved in BST2 trafficking and turnover. BST2 cycles between the plasma membrane, the TGN and the endosomes, with a fraction sorted for lysosomal degradation through an ESCRT-mediated pathway (left panel). Vpu counteracts BST2 restriction activity through (i) displacing it from viral assembly sites by a yet-to-be-determined mechanism involving a “dileucine”-like motif located in its cytoplasmic tail and (ii) down-regulating BST2 cell surface expression level and as such restores viral release. Vpu down-regulates cell surface BST2 by slowing down the PM access of internalized and newly synthesized BST2. Vpu-induced BST2 cell surface down regulation is associated with targeting of the restriction factor for lysosomal degradation through an ubiquitin-dependent mechanism that involves the recruitment of SCFβ-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase complex and the ESCRT machinery. Indeed, through binding to HRS, Vpu enhances the affinity of BST2 for HRS thus accelerating its sorting by the ESCRT machinery for lysosomal degradation. One might propose that through binding with the ESCRT machinery, Vpu may favor the sorting of BST2 at the level of endosomes, thereby reducing its recycling to the plasma membrane (right panel). This figure is adapted from Janvier et al. (2012).

In some cell types such as T-cells and primary macrophages, antagonism of BST2 by Vpu is not associated with decreased expression of cell surface BST2 (Miyagi et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2012), consistent with the view that Vpu promotes viral release by displacing BST2 from viral budding sites at the PM. Using a sophisticated approach, it has been recently suggested that this function relies on the integrity of a “dileucine”-like motif E59VSAL63V in the cytoplasmic tail of Vpu (McNatt et al., 2013), first reported to be essential for Vpu to down-regulate CD4 and BST2 expression and counteract BST2 antiviral activity (Hill et al., 2010; Kueck and Neil, 2012). How this motif contributes to these functions is, however unclear. Vpu EXXXLV motif fits the consensus dileucine – based sorting signal (D/E)XXXL(L/I/M) that mediates binding to the AP complexes. However, evidence for an interaction of Vpu with the AP complexes or a direct contribution of these complexes in Vpu’s functions could not be demonstrated (Kueck and Neil, 2012).

VPU-MEDIATED DEGRADATION OF BST2

In some cell types, Vpu-induced down-regulation of cell surface BST2 is associated with enhanced targeting of the cellular protein to the degradation pathway (Gupta et al., 2009a; Mitchell et al., 2009). This process is ubiquitin-dependent and requires the recruitment of the SCFβ-TrCP complex by Vpu via its DS52GxxS56 motif (Douglas et al., 2009; Goffinet et al., 2009; Mangeat et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009; Tokarev et al., 2010). The importance of β-TrCP in Vpu-mediated antagonism of BST2 antiviral activity remains controversial to date (Douglas et al., 2009; Iwabu et al., 2009; Mangeat et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009; Miyagi et al., 2009; Tervo et al., 2011). BST2 undergoes ubiquitination on lysine residues located in its cytoplasmic tail (Pardieu et al., 2010). Interestingly, Vpu increases BST2 ubiquitination on lysine/serine and threonine residues located in its cytoplasmic tail, as is also observed with CD4 (Tokarev et al., 2010). Mutation of these residues reduces Vpu-induced antagonism of BST2. Consistent with this observation, the short isoform of BST2 lacking these residues shows decreased sensitivity to Vpu antagonism (Tokarev et al., 2010; Cocka and Bates, 2012). One study challenged the requirement of the S3T4S5 residues in Vpu-induced ubiquitination of BST2 (Gustin et al., 2012) but no explanation has been proposed for this discrepancy.

Despite the similarity in the molecular mechanisms underlying Vpu-induced ubiquitination and degradation of CD4 and BST2, the fate of both proteins differs. Indeed, it is now well established that Vpu does not target BST2 for proteasomal degradation but induces β-TrCP-dependent lysosomal sorting of BST2 (Douglas et al., 2009; Iwabu et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2009). In agreement with this notion, we highlighted a major role of Rab7, a regulator of the endo/lysosomal trafficking, in this process (Caillet et al., 2011), and revealed that Vpu enhances ESCRT-mediated sorting of BST2 for degradation (Janvier et al., 2011). The ESCRT machinery is a set of four hetero-oligomeric protein complexes involved in the sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins into vesicles budding into endosomes for their subsequent degradation in the lysosomes. The ESCRT-0 protein HRS (hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate) coordinates this process by linking ubiquitinated cargoes and the ESCRT-I component TSG101 (Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009). We showed that Vpu-mediated down-regulation of BST2 and viral release require HRS, and unveiled an increased affinity of BST2 for HRS upon Vpu expression (Janvier et al., 2011). One might propose that through binding with HRS and BST2, Vpu accelerates ESCRT-mediated sorting of BST2 to the lysosomes, thereby reducing its recycling to the PM (Janvier et al., 2012; Figure 2). Further evidence of the requirement of the ESCRT machinery in Vpu-mediated BST2 degradation was obtained by the characterization of a new component of the ESCRT-I machinery: the protein UBAP1 (Agromayor et al., 2012). Depletion of UBAP1 abolishes Vpu-induced degradation of BST2, but has no impact on Vpu antagonism of BST2 antiviral activity (Agromayor et al., 2012), consistent with the notion that degradation of BST2 is not strictly required for Vpu-mediated antagonism of BST2 (Miyagi et al., 2009; Goffinet et al., 2010).

VPU AND BST2 VIRAL SENSING ACTIVITY

In addition to its activity as a restriction factor of viral release, BST2 has been recently characterized as an innate immune sensor for HIV (Cocka and Bates, 2012; Galao et al., 2012; Tokarev et al., 2013). In 2003, BST2 was first reported to stimulate the activity of the NF-κB family of transcription factors, using a whole-genome cDNA screen (Matsuda et al., 2003). Recent studies further revealed that tethered HIV particles increase BST2 signaling activity, resulting in enhanced production of pro-inflammatory stimuli, consistent with a role of BST2 as a sensor for assembled viruses (Cocka and Bates, 2012; Galao et al., 2012; Tokarev et al., 2013). This function seems separable from its activity as an inhibitor of viral release and relies on the integrity of the non-canonical dual tyrosine residues (Y6XY8) regulating its trafficking (Galao et al., 2012; Tokarev et al., 2013). Whether BST2 trafficking is relevant for its signaling activity is unclear. BST2 was proposed to activate the “canonical” NF-κB pathway through engaging mediators of this pathway via its tyrosine motif (Galao et al., 2012; Tokarev et al., 2013). Regulation of this pathway depends on the activation of the transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1 (TAK1)/TAK1-binding protein 1 and 2 (TAB1 and TAB2) complex, through poly-ubiquitination by E3 ligases of the TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) family (Skaug et al., 2009). Interestingly, BST2 was shown to co-immunoprecipitate with TRAF2, TRAF6 as well as the TAK1/TAB1 complex (Galao et al., 2012; Tokarev et al., 2013).

Vpu was shown to counteract BST2 signaling activity through a β-TrCP-dependent mechanism (Tokarev et al., 2013). Interestingly, over a decade ago, Vpu was shown to sequester β-TrCP away from its substrates and inhibit NF-κB activation by interfering with β-TrCP-mediated degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB (Bour et al., 2001; Besnard-Guerin et al., 2004). Whether this mechanism accounts solely for Vpu-induced inhibition of BST2 signaling activity requires further investigation. Furthermore, many questions remain regarding how viral expression triggers BST2 sensing activity.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Over the past decade, Vpu has emerged as an important asset for viral egress and evasion from the host antiviral mechanisms. Although tremendous progress has been made toward understanding the mechanisms underlying Vpu’s functions, many questions remain regarding how this protein contributes to viral pathogenesis. Vpu’s contribution to viral immune evasion relies on its ability to alter the trafficking of its targets by subverting cellular machineries involved this process. However, despite some similarities in the mechanisms involved, major differences have been reported regarding the site of action of Vpu as well as the fate of its targets in cells. Further characterization of the mechanisms controlling Vpu expression and distribution in cells as well as the interplay with its targets and the host cell machineries might contribute to explain these pleiotropic effects. In keeping with this line of thought, another fascinating aspect worthy of further investigation is the role of Vpu with regards to BST2, in cell-to-cell transmission of HIV through virological synapses. So far, conflicting results have been obtained regarding the impact of both proteins on this process, but intriguingly, they have underlined a multifaceted role of BST2 in HIV pathogenesis (Schubert et al., 1995; Gummuluru et al., 2000; Casartelli et al., 2010; Jolly et al., 2010). Adding to this complexity, BST2 was recently described to act as a host sensor of assembled viruses. Therefore, a more detailed characterization of BST2’s functions in cells as well as its interplay with Vpu would contribute to better comprehend the role of both proteins in viral egress and dissemination. Addressing all these questions might provide important insights into AIDS pathogenesis and contribute to the future development of therapeutic strategies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nicolas Roy and Grégory Pacini conceived the figures and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; Clarisse Berlioz-Torrent edited the manuscript; Katy Janvier wrote the manuscript and contributed to the drawing of the figures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely apologize to the authors whose works will not have been cited due to space limitations. We thank Monica Naughtin for critical reading and editing of our manuscript. Nicolas Roy holds a fellowship from ANRS; Grégory Pacini holds a fellowship from the “Ministère Français de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche”. This work is funded by SIDACTION, the ANR-12-JSV3-0005-01 program and by ANRS.

REFERENCES

- Agromayor M., Soler N., Caballe A., Kueck T., Freund S. M., Allen M. D., et al. (2012). The UBAP1 subunit of ESCRT-I interacts with ubiquitin via a SOUBA domain. Structure 20 414–428 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailes E., Gao F., Bibollet-Ruche F., Courgnaud V., Peeters M., Marx P. A., et al. (2003). Hybrid origin of SIV in chimpanzees. Science 300 1713 10.1126/science.1080657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard-Guerin C., Belaidouni N., Lassot I., Segeral E., Jobart A., Marchal C., et al. (2004). HIV-1 Vpu sequesters beta-transducin repeat-containing protein (betaTrCP) in the cytoplasm and provokes the accumulation of beta-catenin and other SCFbetaTrCP substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 279 788–795 10.1074/jbc.M308068200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billcliff P. G., Rollason R., Prior I., Owen D. M., Gaus K., Banting G. (2013). CD317/tetherin is an organiser of membrane microdomains. J. Cell Sci. 126 1553–1564 10.1242/jcs.112953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour S., Perrin C., Akari H., Strebel K. (2001). The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein inhibits NF-kappa B activation by interfering with beta TrCP-mediated degradation of Ikappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 276 15920–15928 10.1074/jbc.M010533200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillet M., Janvier K., Pelchen-Matthews A., Delcroix-Genete D., Camus G., Marsh M., et al. (2011). Rab7A is required for efficient production of infectious HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002347 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casartelli N., Sourisseau M., Feldmann J., Guivel-Benhassine F., Mallet A., Marcelin A. G., et al. (2010). Tetherin restricts productive HIV-1 cell-to-cell transmission. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000955 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri R., Lindwasser O. W., Smith W. J., Hurley J. H., Bonifacino J. S. (2007). Downregulation of CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is dependent on clathrin and involves direct interaction of Nef with the AP2 clathrin adaptor. J. Virol. 81 3877–3890 10.1128/JVI.02725-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H., Wang J. J., Qi M., Yoon J. J., Chen X., Wen X., et al. (2012). Tetherin/BST-2 is essential for the formation of the intracellular virus-containing compartment in HIV-infected macrophages. Cell Host Microbe 12 360–372 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocka L. J., Bates P. (2012). Identification of alternatively translated Tetherin isoforms with differing antiviral and signaling activities. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002931 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courgnaud V., Formenty P., Akoua-Koffi C., Noe R., Boesch C., Delaporte E., et al. (2003). Partial molecular characterization of two simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) from African colobids: SIVwrc from Western red colobus (Piliocolobus badius) and SIVolc from olive colobus (Procolobus verus). J. Virol. 77 744–748 10.1128/JVI.77.1.744-748.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courgnaud V., Salemi M., Pourrut X., Mpoudi-Ngole E., Abela B., Auzel P., et al. (2002). Characterization of a novel simian immunodeficiency virus with a vpu gene from greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) provides new insights into simian/human immunodeficiency virus phylogeny. J. Virol. 76 8298–8309 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8298-8309.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crise B., Buonocore L., Rose J. K. (1990). CD4 is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein precursor. J. Virol. 64 5585–5593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas J. L., Viswanathan K., McCarroll M. N., Gustin J. K., Fruh K., Moses A. V. (2009). Vpu directs the degradation of the human immunodeficiency virus restriction factor BST-2/Tetherin via a {beta}TrCP-dependent mechanism. J. Virol. 83 7931–7947 10.1128/JVI.00242-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube M., Paquay C., Roy B. B., Bego M. G., Mercier J., Cohen E. A. (2011). HIV-1 Vpu antagonizes BST-2 by interfering mainly with the trafficking of newly synthesized BST-2 to the cell surface. Traffic 12 1714–1729 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01277.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galao R. P., Le Tortorec A., Pickering S., Kueck T., Neil S. J. (2012). Innate sensing of HIV-1 assembly by Tetherin induces NFkappaB-dependent proinflammatory responses. Cell Host Microbe 12 633–644 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Bailes E., Robertson D. L., Chen Y., Rodenburg C. M., Michael S. F., et al. (1999). Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397 436–441 10.1038/17130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet C., Allespach I., Homann S., Tervo H. M., Habermann A., Rupp D., et al. (2009). HIV-1 antagonism of CD317 is species specific and involves Vpu-mediated proteasomal degradation of the restriction factor. Cell Host Microbe 5 285–297 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet C., Homann S., Ambiel I., Tibroni N., Rupp D., Keppler O. T., et al. (2010). Antagonism of CD317 restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) particle release and depletion of CD317 are separable activities of HIV-1 Vpu. J. Virol. 84 4089–4094 10.1128/JVI.01549-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummuluru S., Kinsey C. M., Emerman M. (2000). An in vitro rapid-turnover assay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication selects for cell-to-cell spread of virus. J. Virol. 74 10882–10891 10.1128/JVI.74.23.10882-10891.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K., Hue S., Schaller T., Verschoor E., Pillay D., Towers G. J. (2009a). Mutation of a single residue renders human tetherin resistant to HIV-1 Vpu-mediated depletion. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000443 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K., Mlcochova P., Pelchen-Matthews A., Petit S. J., Mattiuzzo G., Pillay D., et al. (2009b). Simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein counteracts tetherin/BST-2/CD317 by intracellular sequestration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 20889–20894 10.1073/pnas.0907075106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin J. K., Douglas J. L., Bai Y., Moses A. V. (2012). Ubiquitination of BST-2 protein by HIV-1 Vpu protein does not require lysine, serine, or threonine residues within the BST-2 cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 287 14837–14850 10.1074/jbc.M112.349928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermann A., Krijnse-Locker J., Oberwinkler H., Eckhardt M., Homann S., Andrew A., et al. (2010). CD317/tetherin is enriched in the HIV-1 envelope and downregulated from the plasma membrane upon virus infection. J. Virol. 84 4646–4658 10.1128/JVI.02421-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds J., Wang J. J., Yi H., Spearman P. (2010). Immunoelectron microscopic evidence for Tetherin/BST2 as the physical bridge between HIV-1 virions and the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000749 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser H., Lopez L. A., Yang S. J., Oldenburg J. E., Exline C. M., Guatelli J. C., et al. (2010). HIV-1 Vpu and HIV-2 Env counteract BST-2/tetherin by sequestration in a perinuclear compartment. Retrovirology 7 51 10.1186/1742-4690-7-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. S., Ruiz A., Schmitt K., Stephens E. B. (2010). Identification of amino acids within the second alpha helical domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu that are critical for preventing CD4 cell surface expression. Virology 397 104–112 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwabu Y., Fujita H., Kinomoto M., Kaneko K., Ishizaka Y., Tanaka Y., et al. (2009). HIV-1 accessory protein Vpu internalizes cell-surface BST-2/tetherin through transmembrane interactions leading to lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 284 35060–35072 10.1074/jbc.M109.058305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar M. A., Nayak D. P. (1990). Intracellular interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (ARV-2) envelope glycoprotein gp160 with CD4 blocks the movement and maturation of CD4 to the plasma membrane. J. Virol. 64 6297–6304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier K., Pelchen-Matthews A., Renaud J. B., Caillet M., Marsh M., Berlioz-Torrent C. (2011). The ESCRT-0 component HRS is required for HIV-1 Vpu-mediated BST-2/tetherin down-regulation. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001265 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier K., Roy N., Berlioz-Torrent C. (2012). Role of the endosomal ESCRT machinery in HIV-1 Vpu-induced down-regulation of BST2/tetherin. Curr. HIV Res. 10 315–320 10.2174/157016212800792414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia B., Serra-Moreno R., Neidermyer W., Rahmberg A., Mackey J., Fofana I. B., et al. (2009). Species-specific activity of SIV Nef and HIV-1 Vpu in overcoming restriction by tetherin/BST2. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000429 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly C., Booth N. J., Neil S. J. (2010). Cell-cell spread of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 overcomes tetherin/BST-2 mediated restriction in T cells. J. Virol. 84 12185–12199 10.1128/JVI.01447-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Ode H., Yoshida T., Sato K., Gee P., Yamamoto S. P., et al. (2011). Identification of amino acids in the human tetherin transmembrane domain responsible for HIV-1 Vpu interaction and susceptibility. J. Virol. 85 932–945 10.1128/JVI.01668-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueck T., Neil S. J. (2012). A cytoplasmic tail determinant in HIV-1 Vpu mediates targeting of tetherin for endosomal degradation and counteracts interferon-induced restriction. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002609 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupzig S., Korolchuk V., Rollason R., Sugden A., Wilde A., Banting G. (2003). Bst-2/HM1.24 is a raft-associated apical membrane protein with an unusual topology. Traffic 4 694–709 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguette N., Sobhian B., Casartelli N., Ringeard M., Chable-Bessia C., Segeral E., et al. (2011). SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474 654–657 10.1038/nature10117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau D., Kwan W., Guatelli J. (2011). Role of the endocytic pathway in the counteraction of BST-2 by human lentiviral pathogens. J. Virol. 85 9834–9846 10.1128/JVI.02633-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Tortorec A., Neil S. J. (2009). Antagonism to and intracellular sequestration of human tetherin by the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 83 11966–11978 10.1128/JVI.01515-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magadan J. G., Bonifacino J. S. (2012). Transmembrane domain determinants of CD4 Downregulation by HIV-1 Vpu. J. Virol. 86 757–772 10.1128/JVI.05933-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magadan J. G., Perez-Victoria F. J., Sougrat R., Ye Y., Strebel K., Bonifacino J. S. (2010). Multilayered mechanism of CD4 downregulation by HIV-1 Vpu involving distinct ER retention and ERAD targeting steps. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000869 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldarelli F., Chen M. Y., Willey R. L., Strebel K. (1993). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is an oligomeric type I integral membrane protein. J. Virol. 67 5056–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malim M. H., Bieniasz P. D. (2012). HIV Restriction factors and mechanisms of evasion. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2:a006940 10.1101/cshperspect.a006940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malim M. H., Emerman M. (2008). HIV-1 accessory proteins–ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe 3 388–398 10.1016/j.chom.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeat B., Gers-Huber G., Lehmann M., Zufferey M., Luban J., Piguet V. (2009). HIV-1 Vpu neutralizes the antiviral factor Tetherin/BST-2 by binding it and directing its beta-TrCP2-dependent degradation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000574 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margottin F., Bour S. P., Durand H., Selig L., Benichou S., Richard V., et al. (1998). A novel human WD protein, h-beta TrCp, that interacts with HIV-1 Vpu connects CD4 to the ER degradation pathway through an F-box motif. Mol. Cell 1 565–574 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama N., Kuronita T., Tanaka R., Muto T., Hirota Y., Takigawa A., et al. (2009). HM1.24 is internalized from lipid rafts by clathrin-mediated endocytosis through interaction with alpha-adaptin. J. Biol. Chem. 284 15927–15941 10.1074/jbc.M109.005124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A., Suzuki Y., Honda G., Muramatsu S., Matsuzaki O., Nagano Y., et al. (2003). Large-scale identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-kappaB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene 22 3307–3318 10.1038/sj.onc.1206406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNatt M. W., Zang T., Bieniasz P. D. (2013). Vpu binds directly to tetherin and displaces it from nascent virions. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003299 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R. S., Katsura C., Skasko M. A., Fitzpatrick K., Lau D., Ruiz A., et al. (2009). Vpu antagonizes BST-2-mediated restriction of HIV-1 release via beta-TrCP and endo-lysosomal trafficking. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000450 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi E., Andrew A. J., Kao S., Strebel K. (2009). Vpu enhances HIV-1 virus release in the absence of Bst-2 cell surface down-modulation and intracellular depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 2868–2873 10.1073/pnas.0813223106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll M., Andersson S. K., Smed-Sorensen A., Sandberg J. K. (2010). Inhibition of lipid antigen presentation in dendritic cells by HIV-1 Vpu interference with CD1d recycling from endosomal compartments. Blood 116 1876–1884 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S. J. (2013). The antiviral activities of tetherin. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 371 67–104 10.1007/978-3-642-37765-5_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S. J., Zang T., Bieniasz P. D. (2008). Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature 451 425–430 10.1038/nature06553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardieu C., Vigan R., Wilson S. J., Calvi A., Zang T., Bieniasz P., et al. (2010). The RING-CH ligase K5 antagonizes restriction of KSHV and HIV-1 particle release by mediating ubiquitin-dependent endosomal degradation of tetherin. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000843 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Caballero D., Zang T., Ebrahimi A., McNatt M. W., Gregory D. A., Johnson M. C., et al. (2009). Tetherin inhibits HIV-1 release by directly tethering virions to cells. Cell 139 499–511 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering S., Hue S., Kim E. Y., Reddy S., Wolinsky S. M., Neil S. J. (2014). Preservation of tetherin and CD4 counter-activities in circulating Vpu alleles despite extensive sequence variation within HIV-1 infected individuals. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003895 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C., Stenmark H. (2009). The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature 458 445–452 10.1038/nature07961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray N., Doms R. W. (2006). HIV-1 coreceptors and their inhibitors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 303 97–120 10.1007/978-3-540-33397-5_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollason R., Korolchuk V., Hamilton C., Schu P., Banting G. (2007). Clathrin-mediated endocytosis of a lipid-raft-associated protein is mediated through a dual tyrosine motif. J. Cell Sci. 120 3850–3858 10.1242/jcs.003343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter D., Schindler M., Specht A., Landford W. N., Munch J., Kim K. A., et al. (2009). Tetherin-driven adaptation of Vpu and Nef function and the evolution of pandemic and non-pandemic HIV-1 strains. Cell Host Microbe 6 409–421 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S., Fritz J. V., Bitzegeio J., Fackler O. T., Keppler O. T. (2011). HIV-1 Vpu blocks recycling and biosynthetic transport of the intrinsic immunity factor CD317/tetherin to overcome the virion release restriction. MBio 2 e00036–00011 10.1128/mBio.00036-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert H. L., Zhai Q., Sandrin V., Eckert D. M., Garcia-Maya M., Saul L., et al. (2010). Structural and functional studies on the extracellular domain of BST2/tetherin in reduced and oxidized conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 17951–17956 10.1073/pnas.1008206107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert U., Clouse K. A., Strebel K. (1995). Augmentation of virus secretion by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein is cell type independent and occurs in cultured human primary macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Virol. 69 7699–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Moreno R., Jia B., Breed M., Alvarez X., Evans D. T. (2011). Compensatory changes in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 confer resistance to tetherin/BST-2 in a pathogenic nef-deleted SIV. Cell Host Microbe 9 46–57 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A. H., Sowrirajan B., Davis Z. B., Ward J. P., Campbell E. M., Planelles V., et al. (2010). Degranulation of natural killer cells following interaction with HIV-1-infected cells is hindered by downmodulation of NTB-A by Vpu. Cell Host Microbe 8 397–409 10.1016/j.chom.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy A. M., Gaddis N. C., Choi J. D., Malim M. H. (2002). Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418 646–650 10.1038/nature00939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skasko M., Wang Y., Tian Y., Tokarev A., Munguia J., Ruiz A., et al. (2012). HIV-1 Vpu protein antagonizes innate restriction factor BST-2 via lipid-embedded helix-helix interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 287 58–67 10.1074/jbc.M111.296772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug B., Jiang X., Chen Z. J. (2009). The role of ubiquitin in NF-kappaB regulatory pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78 769–796 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.102750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strebel K., Klimkait T., Martin M. A. (1988). A novel gene of HIV-1, vpu, and its 16-kilodalton product. Science 241 1221–1223 10.1126/science.3261888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M., Owens C. M., Perron M. J., Kiessling M., Autissier P., Sodroski J. (2004). The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in old world monkeys. Nature 427 848–853 10.1038/nature02343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo H. M., Homann S., Ambiel I., Fritz J. V., Fackler O. T., Keppler O. T. (2011). Beta-TrCP is dispensable for Vpu’s ability to overcome the CD317/Tetherin-imposed restriction to HIV-1 release. Retrovirology 8 9 10.1186/1742-4690-8-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarev A., Suarez M., Kwan W., Fitzpatrick K., Singh R., Guatelli J. (2013). Stimulation of NF-kappaB activity by the HIV restriction factor BST2. J. Virol. 87 2046–2057 10.1128/JVI.02272-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarev A. A., Munguia J., Guatelli J. C. (2010). Serine-threonine ubiquitination mediates downregulation of BST-2/tetherin and relief of restricted virion release by HIV-1 Vpu. J. Virol. 85 51–63 10.1128/JVI.01795-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme N., Goff D., Katsura C., Jorgenson R. L., Mitchell R., Johnson M. C., et al. (2008). The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe 3 245–252 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S., Bieniasz P. D. (2013). Mechanism of HIV-1 virion entrapment by tetherin. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003483 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigan R., Neil S. J. (2010). Determinants of tetherin antagonism in the transmembrane domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (Hiv-1) Vpu protein. J. Virol. 84 12958–12970 10.1128/JVI.01699-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildum S., Schindler M., Munch J., Kirchhoff F. (2006). Contribution of Vpu, Env, and Nef to CD4 down-modulation and resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected T cells to superinfection. J. Virol. 80 8047–8059 10.1128/JVI.00252-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey R. L., Maldarelli F., Martin M. A., Strebel K. (1992a). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces rapid degradation of CD4. J. Virol. 66 7193–7200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey R. L., Maldarelli F., Martin M. A., Strebel K. (1992b). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein regulates the formation of intracellular gp160-CD4 complexes. J. Virol. 66 226–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Wilson S. J., Landford W. C., Virgen B., Gregory D., Johnson M. C., et al. (2009). Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency viruses are tetherin antagonists. Cell Host Microbe 6 54–67 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]