Abstract

Negative frequency-dependent sexual selection maintains striking polymorphisms in secondary sexual traits in several animal species. Here, we test whether frequency of beardedness modulates perceived attractiveness of men's facial hair, a secondary sexual trait subject to considerable cultural variation. We first showed participants a suite of faces, within which we manipulated the frequency of beard thicknesses and then measured preferences for four standard levels of beardedness. Women and men judged heavy stubble and full beards more attractive when presented in treatments where beards were rare than when they were common, with intermediate preferences when intermediate frequencies of beardedness were presented. Likewise, clean-shaven faces were least attractive when clean-shaven faces were most common and more attractive when rare. This pattern in preferences is consistent with negative frequency-dependent selection.

Keywords: sexual selection, frequency dependence, facial hair, human evolution

1. Introduction

Understanding the maintenance of additive genetic variation under selection remains a core challenge in population genetics [1]. In the sexual selection literature, this issue underpins the ‘lek paradox’ [2]. A population under strong sexual selection might be expected to converge on a single ‘most attractive’ phenotype, but attractive traits often show high additive genetic variance [3]. In understanding the maintenance of genetic variation in attractive traits, it is worth noting that an individual's attractiveness depends not only on their phenotype, but also on the distribution of rivals' phenotypes.

In some cases, rarity in ornamentation can be advantageous. For example, lower avoidance of rare colour morphs by pollinators of the orchid Dactylorhiza sambucina may maintain purple–yellow flower polymorphisms [4]. In guppies (Poecilia reticulata), polymorphic coloration is restricted to males [5]. Males bearing rare colour patterns enjoy greater survivability in the wild [6], and enhanced mating success in both the laboratory [7,8] and wild [9]. Preferences for rare phenotypes can exert negative frequency-dependent selection, a form of selection that prevents the loss of rare alleles, thus maintaining additive genetic variance [3]. Negative frequency-dependent mate choice can arise via a number of mechanisms, including avoiding familiar individuals [10,11], individuals who resemble previous mates [12] or preferring mates with novel or rare sexual signals [8].

In contemporary humans, traits that can be manipulated via grooming, and cosmetics might also be expected to converge on a single optimum and yet fashions in hairstyles and beards change regularly. While variation in men's natural patterning and density of facial hair reflects androgenic effects [13], men can easily groom or remove their beards, suggesting that cultural influences determine the attractiveness of facial hair. Although beards enhance ratings of age, masculinity and dominance [14,15], their role in male facial attractiveness is equivocal. Women preferred light stubble in one study [14], heavy stubble in another [16] and clean-shaven, light stubble and heavy stubble equally over full beards in a third study [17].

These equivocal findings might simply reflect culturally variable tastes in fashion, with different samples expressing geographically or spatially different mean preferences. However, a man's decision to groom his beard might occur in response to both prevailing preferences and fashions. Robinson [18] found among men photographed in the London Illustrated News magazine from 1842 to 1972, facial hairstyles showed patterned oscillations in frequency and popularity. Thus, sideburns peaked in frequency in 1853, sideburns and moustaches in 1877, beards in 1892 and moustaches from 1917 to 1919. Popularity in each style of facial hair rose gradually, peaked and then decayed following maximum popularity to be replaced by a newer, perhaps more novel, style [18]. Barber [19] demonstrated using Robinson's [18] data that men were more bearded when there were more males than females in the potential marriage pool, suggesting that the premium on beardedness fluctuates with the strength of intrasexual competition.

While changes in fashion cannot alter the genetic basis of preferences, if men tailored their grooming in order to be distinctive, possibly spurred by imitation of culturally influential early adopters, that could confer an advantage to rare-beard styles that would decay as a style grew more popular, resulting in negative frequency-dependent preferences. Here, we test the effects of facial hair grooming on women's preferences for men's beards. We hypothesized that the attractiveness of beards is influenced by the frequencies of different degrees of facial hair styles and that the attractiveness of a beard type would be elevated when that beard type was rare, compared with when it was common. We presented participants with a suite of faces, within which we manipulated the frequency of beard thicknesses and then measured preferences for four standard levels of beardedness.

2. Methods

(a). Stimuli

Thirty-six men (mean age ± s.d. = 27.08 ± 5.61 years) of European descent were photographed when clean-shaven, with five days of regrowth (light stubble), 10 days of regrowth (heavy stubble) and at least four weeks of untrimmed growth (full beard). Photographs were taken under controlled lighting from 1.5 m and cropped to show only the neck and face (figure 1).

Figure 1.

One of the models when clean-shaven, with light stubble, heavy stubble and full beard.

(b). Procedure

Participants viewed two sets of faces. The first familiarized participants with a set of faces corresponding to the treatment to which participants were assigned (rare-beard, rare clean-shaven and even). The second used a standardized set of faces to gauge the attractiveness of men's facial hair.

From the 36 models, 24 were used to populate three experimental treatments in which the frequency of beardedness varied: the ‘rare beardedness’ treatment included only clean-shaven faces; the ‘rare clean-shaven’ treatment included only fully bearded faces and the ‘even treatment’ included six models in each of the four levels of facial hair. Each model was used only once per experimental treatment. For each treatment, models were also drawn at random, without replacement, ensuring that participants saw different combinations of faces in each level of facial hair. All images were rated for attractiveness on a Likert scale where −4 is very unattractive to 4 is very attractive.

To gauge attractiveness of facial hair, we measured participants' responses to a standard set of 12 faces, following directly on from the experimental treatment. The 12 models were not used in the preceding experimental treatment. Three models were randomly assigned to each of the four levels of facial hair (clean-shaven, light stubble, heavy stubble and beard) and rated using the same Likert scale as above. Participants had no time restriction when performing ratings with no break between the two treatments.

This study was conducted online (www.socialsci.com). Participants were recruited via social media outlets (i.e. Facebook), volunteered to see and rate men's faces for attractiveness and were randomly assigned to one of the three treatments. After completing the ratings, participants provided their sexual orientation using the Kinsey scale, their partners' and fathers' beardedness.

(c). Participants

Only bisexual or heterosexual female and heterosexual male participants were retained, leaving 1453 women (mean age ± s.d. = 26.17 ± 7.28 years) and 213 men (28.35 ± 10.11). Sample sizes and ages within each treatment were rare clean-shaven (female N = 479, 26.30 ± 7.19; male N = 70; 29.91 ± 11.58); rare beards (female N = 502, 26.02 ± 7.68; male N = 76; 28.49 ± 9.07); the even treatment (female N = 472, 26.19 ± 6.95; male N = 67; 26.55 ± 9.43). Ethnicities were 70.47% European, 9.6% Asian, 6.12% Central/South American, 2.46% Oceania, 2.28% African/Middle Eastern, 1.86% Native North American and 7.2% chose not to answer.

3. Results

Ratings for the three models within each of the four categories of facial hair had reasonable internal consistency (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Thus, for each participant, we calculated an aggregate attractiveness response to the three faces within each of the four levels of beardedness. These scores formed the dependent variables in a repeated-measures ANCOVA where facial hair (clean-shaven, light stubble, heavy stubble and full beards) was the within-subjects fixed-factor and treatment (rare clean-shaven, rare beards and even) and sex (male, female) were between-subjects factors. Participant's age was a covariate as it differed between the sexes and treatments (electronic supplementary material, table S2).

There was a significant main effect of facial hair on attractiveness (table 1). Beards, light and heavy stubble were more attractive than clean-shaven faces (all t1665 ≥ 25.59, all p < 0.001), heavy stubble was more attractive than beards (t1665 = 2.99, p = 0.003). Preferences for light versus heavy stubble and light stubble versus beards did not differ significantly (all t1665 ≤ 1.74, all p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Repeated-measures analysis of variance on the effects of facial hair, sex and treatment on attractiveness.

| F | d.f. | P |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| within-subjects effects | ||||

| facial haira | 36.62 | 2.5, 4181.2 | <0.001 | 0.022 |

| facial hair × agea | 1.12 | 2.5, 4181.2 | 0.336 | 0.001 |

| facial hair × treatmenta | 11.23 | 5.0, 4181.2 | <0.001 | 0.013 |

| facial hair × sexa | 4.66 | 2.5, 4181.2 | 0.005 | 0.003 |

| facial hair × treatment × sexa | 1.39 | 5.0, 4181.2 | 0.224 | 0.002 |

| between-subjects effects | ||||

| age | 12.33 | 1, 1659 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| treatment | 0.22 | 2, 1659 | 0.799 | <0.001 |

| sex | 5.35 | 1, 1659 | 0.021 | 0.003 |

| treatment × sex | 0.03 | 2, 1659 | 0.967 | <0.001 |

aGreenhouse–Geisser adjusted degree of freedom (rounded to one decimal place), F-values, p-values and  .

.

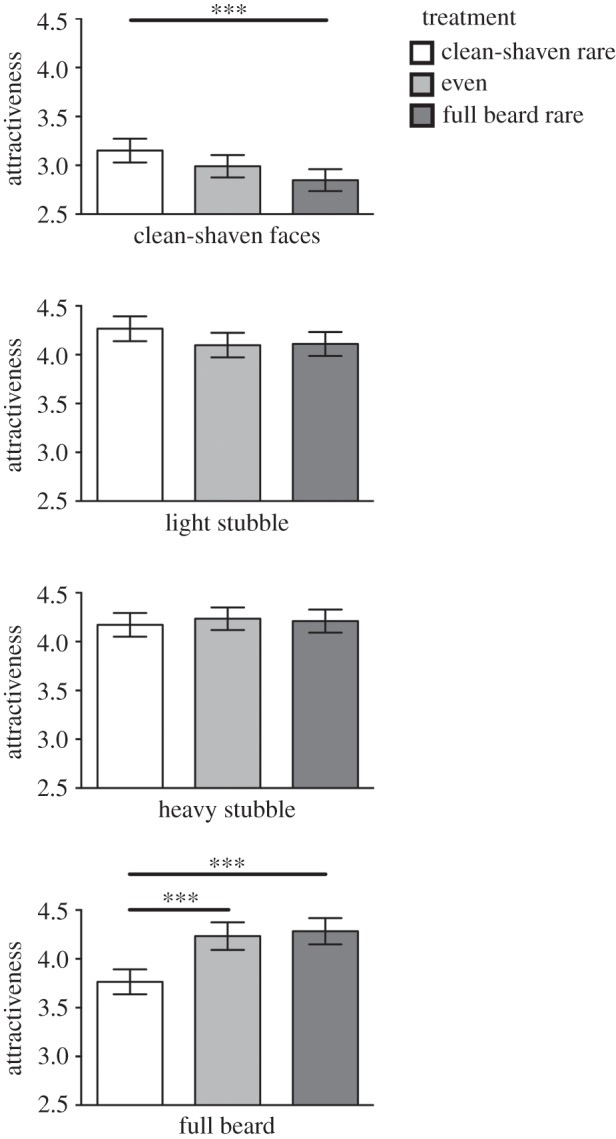

There was a significant facial hair × treatment interaction (table 1). Between treatments comparisons revealed that when clean-shaven faces were rare, clean-shaven faces received higher attractiveness ratings than when beards were rare (t1125 = 3.60, p < 0.001). Compared with when clean-shaven faces were rare, full beards were more attractive when beards were rare (t1125 = 5.46, p < 0.001) and in the even treatment (t1086 = 4.80, p < 0.001; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean attractiveness ratings (±95% CI) for facial hair within each experimental treatment. Data from the Likert scales were re-scaled for the figure to reflect positive values by adding 4. ***p < .001.

Within treatments, beards, light and heavy stubble were more attractive than clean-shaven faces for rare beard (all t577 ≥ 22.97, all p < 0.001), rare clean-shaven (all t548 ≥ 7.84, all p < 0.001) and even (all t538 ≥ 15.80, all p < 0.001) treatments. For the rare-beard treatment, beards and heavy stubble were rated as significantly more attractive than light stubble (t577 ≥ 2.26, all p < 0.05), but ratings for beards and heavy stubble did not differ significantly (t577 = 1.33, p = 0.185). In the rare clean-shaven treatment, light and heavy stubble were more attractive than beards (all t548 ≥ 5.92, all p < 0.001), and ratings between light and heavy stubble did not differ significantly (t548 = 1.87, p > 0.05). For the even treatment, heavy stubble was more attractive than light stubble (t538 = 2.74, p = 0.006). However, no other paired comparisons were significant (all t538 ≤ 1.89, all p > 0.05).

There was a significant facial hair × sex interaction (table 1). Beards, light and heavy stubble were more attractive than clean-shaven faces among men (all t212 ≥ 9.34, all p < 0.001) and women (all t1452 ≥ 23.82, all p < 0.001). Women gave higher ratings to light and heavy stubble than beards (all t1452 ≥ 2.42, all p < 0.05). Men rated beards higher than light (t212 = 2.11, p = 0.036), but not heavy stubble (t212 = 1.31, p = 0.191). Ratings between light and heavy stubble were not significant among men (t212 = 1.20, p = 0.230) or women (t1452 = 1.40, p = 0.162). Men gave higher ratings than women for clean-shaven faces and full beards (all t1664 ≥ 3.24, all p < 0.001), but not light or heavy stubble (t1664 ≤ 1.16, p ≥ 0.248; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). While women's preferences for beardedness were positively related to their current partner's, but not their father's beardedness, the effects of frequency on preferences remained (electronic supplementary material, S2–S4).

4. Discussion

Attractiveness ratings for styles of facial hair changed in response to their frequency. When beards were rare, hirsute faces were more attractive than when beards were common, and beards achieved intermediate attractiveness in the even treatment. Conversely, when clean-shaven faces were rare, clean-shaven faces and light stubble enjoyed their greatest attractiveness, and beards became less attractive. There was not an inversion of preferences, such as clean-shaven faces becoming more attractive than beards when rare and clean-shaven faces were rated lowest in all treatments. However, the mean attractiveness of a suite of faces is altered by the frequency of beards, suggesting negative frequency-dependence could alter the cultural dynamics by which facial hair fashions vary.

Concordant effects of frequency-dependent preferences among men and women might reflect a domain-general effect of novelty. Frost [20] suggested the variation in female blond, brown and red hair between European populations spread, geographically, from where they first arose, via negative frequency-dependent preferences for novelty. There is some evidence that men's preferences increase for brown hair when it is rare [21] and for unfamiliar (i.e. novel) female faces [22]. However, further studies investigating novelty effects in other traits would be valuable.

As an alternative to negative frequency-dependence, shared preferences for novel and innovative traits might reflect cultural evolutionary effects. Novelty effects, possibly spurred by imitation of influential early adopters, may affect the rise in frequency of new fashions. Interestingly, facial hair fashions may fluctuate in response to surrounding intrasexual competition [19] and bearded faces are rated as looking older, more masculine and socially dominant than clean-shaven faces [14,15]. This suggests that culturally driven perceptions of the novelty of beardedness may influence temporal variation in men's attractiveness and status among peers. Although these processes remain to be more fully explored, negative frequency-dependent cultural mechanisms may have the potential to maintain variation in novel or influential traits within and between populations.

Ethics approval was provided by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC no. 1878).

Data accessibility

All raw data can be found as electronic supplementary material. Data were collected anonymously and participants were each assigned a code to ensure anonymity. Formal consent included that information collected would be available for publications and presentations at conferences.

References

- 1.Barton NH, Keightley PD. 2002. Understanding quantitative genetic variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 11–21. ( 10.1038/nrg700) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotiaho JS, Simmons LW, Tomkins JL. 2001. Towards a resolution of the lek paradox. Nature 410, 684–686. ( 10.1038/35070557) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokko H, Jennions MD, Houde A. 2007. Evolution of frequency-dependent mate choice: keeping up with fashion trends. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 1317–1324. ( 10.1098/rspb.2007.0043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gigord LD, Macnair MR, Smithson A. 2001. Negative frequency-dependent selection maintains a dramatic flower color polymorphism in the rewardless orchid Dactylorhiza sambucina (L.) Soo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 6253–6255. ( 10.1073/pnas.111162598) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houde AE. 1997. Sex, color and mate choice in guppies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olendorf R, Rodd FH, Punzalan D, Houde AE, Hurt C, Reznick DN, Hughes KA. 2006. Frequency-dependent survival in natural guppy populations. Nature 44, 633–636. ( 10.1038/nature04646) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farr JA. 1977. Male rarity or novelty, female choice behavior, and sexual selection in the guppy, Poecilia reticulata Peters (Pisces: Poeciliidae). Evolution 31, 162–168. ( 10.2307/2407554) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes KA, Du L, Rodd FH, Reznick DN. 1999. Familiarity leads to female mate preference for novel males in the guppy (Poecilia reticulate). Anim. Behav. 58, 907–916. ( 10.1006/anbe.1999.1225) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes KA, Houde AE, Price AC, Rodd FH. 2013. Mating advantage for rare males in wild guppy populations. Nature 503, 108–110. ( 10.1038/nature12717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley JL, Graves JA, Magurran AE. 1999. Familiarity breeds contempt in guppies. Nature 401, 661–662. ( 10.1038/44314) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zajitschek SR, Evans JP, Brooks R. 2006. Independent effects of familiarity and mating preferences for ornamental traits on mating decisions in guppies. Behav. Ecol. 17, 911–916. ( 10.1093/beheco/arl026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakley AL, Houde AE. 2004. Possible role of female discrimination against ‘redundant’ males in the evolution of colour pattern polymorphism in guppies. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S299–S301. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0165) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randall VA. 2008. Androgens and hair growth. Dermatol. Ther. 21, 314–328. ( 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00214.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neave N, Shields K. 2008. The effects of facial hair manipulation on female perceptions of attractiveness, masculinity, and dominance in male faces. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 45, 373–377. ( 10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixson BJ, Vasey PL. 2012. Beards augment perceptions of men's age, social status, and aggressiveness, but not attractiveness. Behav. Ecol. 23, 481–490. ( 10.1093/beheco/arr214) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixson BJ, Brooks RC. 2013. The role of facial hair in women's perceptions of men's attractiveness, health, masculinity and parenting abilities. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 236–241. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.02.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixson BJ, Tam JC, Awasthy M. 2013. Do women's preferences for men's facial hair change with reproductive status? Behav. Ecol. 24, 708–716. ( 10.1093/beheco/ars211) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson DE. 1976. Fashions in shaving and trimming of the beard: the men of the Illustrated London News, 1842–1972. Am. J. Sociol. 81, 1133–1141. ( 10.1086/226188) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber N. 2001. Mustache fashion covaries with a good marriage market for women. J. Nonverbal. Behav. 25, 261–272. ( 10.1023/A:1012515505895) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frost P. 2006. European hair and eye color: a case of frequency-dependent sexual selection? Evol. Hum. Behav. 27, 85–103. ( 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.07.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thelen TH. 1983. Minority type human mate preference. Soc. Biol. 30, 162–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little AC, DeBruine LM, Jones BC. 2013. Sex differences in attraction to familiar and unfamiliar opposite-sex faces: men prefer novelty and women prefer familiarity. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1–9. ( 10.1007/s10508-013-0120-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All raw data can be found as electronic supplementary material. Data were collected anonymously and participants were each assigned a code to ensure anonymity. Formal consent included that information collected would be available for publications and presentations at conferences.