Abstract

Intraperitoneal infection known as peritonitis is a major killer in the practice of clinical surgery. Tertiary peritonitis (TP) may be defined as intra-abdominal infection that persists or recurs ³48 h following successful and adequate surgical source control. A planned or on-demand relaparotomy after an initial operation is probably most frequent way to diagnose TP, but is a late event to occur. Hence it is desirable to have timely and nonoperative diagnosis of TP after the initial operation and subsequent initiation of an appropriate therapy to reduce the complications and to improve the outcome.

Keywords: Mannheim peritonitis index, simplified acute physiology score II, tertiary peritonitis

INTRODUCTION

Intraperitoneal infection known as peritonitis is a major killer in the practice of clinical surgery and it is also one of the most frequent diagnoses in a surgical intensive care unit (ICU) leading to severe sepsis.[1] It can be classified as — primary, secondary, and tertiary peritonitis (TP). Primary peritonitis lacks an identifiable anatomical derangement. It is also known as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and has a low incidence on surgical ICUs as it is managed purely without any surgical intervention and mostly by physician or intensivist. Secondary peritonitis is the most common entity in critical surgical patients and is defined as an infection of the peritoneal cavity resulting from hollow viscus perforation, anastomotic leak, ischemic necrosis, or other injuries of the gastrointestinal tract.[2] An exploratory laparotomy may be warranted to achieve surgical control of the source of infectious focus and reduction of the bacterial load. TP may be defined as a severe recurrent or persistent intra-abdominal infection after apparently successful and adequate surgical source control of secondary peritonitis.[2] Though it is less common entity but comprises of a prolonged systemic inflammation leading to a high chance of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock; and therefore mortality in TP ranges between 30 and 64%.[1,2,3,4,5] There is significant difference between the microbial flora in tertiary and secondary peritonitis and TP comprises of mostly opportunistic and nosocomial facultative pathogenic bacteria and fungi (e.g., Enterococci, Enterobacter, and Candida). The development of multidrug resistance has also been observed in microbes causing TP due to use of broad spectrum antibiotic therapy.

DEFINITION OF TERTIARY PERITONITIS

The standard treatment for secondary peritonitis is an urgent exploratory laparotomy with surgical source control and proper antibiotic therapy. However, a few patients develop persistent intra-abdominal infection, an altered microbial flora, failure of the immune response, and progressive organ dysfunction leading to high mortality; which may be referred to as TP. The debate continues about the definition of TP and some workers deny the existence of TP as a distinct entity. Various definitions have emphasized on failed surgical source control or inadequate antibiotic therapy of secondary peritonitis or even impaired host response to peritoneal infection.[6] This heterogeneity of definitions invited clinicians and intensivists to work out the exact parameters to label a clinical situation as TP.

The latest ICU consensus conference guideline provides a precise definition of TP as intra-abdominal infection that persists or recur ≥48 h following successful and adequate surgical source control.[2] This definition contains two essential conditions, which have to be met: The time period (≥48 h) and successful surgical source control.

However, there is a consensus that secondary peritonitis and TP exist in a continuum and the transition between both may be quite subtle. Although TP may be diagnosed during relaparotomy as a simple discrete point in the illness, in reality, it evolves gradually over several hours or days.

RISK FACTORS AND MICROBIAL FLORA OF TERTIARY PERITONITIS

Age of the patient, underlying etiology of peritonitis, malnutrition, and presence of multidrug resistant microorganisms has been some of the important epidemiologic and clinical risk factors which may predispose towards TP. Many workers have shown that there is a microbial shift in TP towards Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Candida albicans, and other opportunistic bacteria and fungi.[7,8,9]

DIAGNOSIS OF TP

The differentiation between secondary and TP becomes really difficult as there is usually a continuum between the two and the exact time point when secondary peritonitis turns into TP is often missed. In the cases when secondary peritonitis is diagnosed during the initial operation, a successful attempt of surgical source control (e.g., exteriorization of perforated viscus) is often enough to save prolong morbidity and mortality in the majority of patients. However, a reoperation may be indicated in a subset of patients who show clinical signs of recurrent or persistent intra-abdominal infection in spite of apparently successful source control, which is referred to as TP. It is important to differentiate the entity with an ongoing secondary peritonitis developing because of failure of the surgical attempt of the source control (e.g., failure of the surgical procedure or missed pathology), whereas in TP there is no obvious anatomical defect or perforation of the hollow viscus. A planned or on-demand relaparotomy after an initial operation is probably most frequent way to diagnose TP, but is a late event to occur.[10,11] Hence, it is desirable to have timely and nonoperative diagnosis of TP after the initial operation and subsequent initiation of an appropriate therapy to reduce the complications and to improve the outcome. It is also essential to identify patients at risk for developing TP as early as possible after initial operation for secondary peritonitis.

PREDICTIVE PARAMETERS AND DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGE

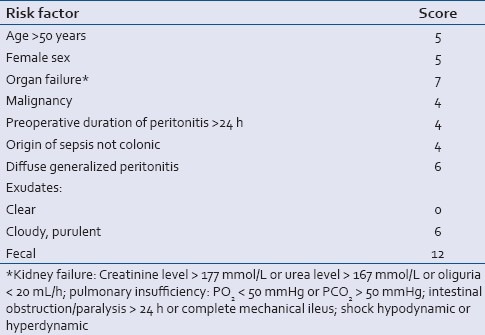

There has been no consensus till date regarding value of clinical and laboratory parameters and scoring systems for sufficient diagnosis and monitoring of TP.[5] The ICU consensus conference suggested three categories for the diagnostic certainty of TP, that is, microbiologically confirmed, probable, and possible.[2] Mannheim Peritonitis Index, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), and C-reactive protein are three early and easily accessible parameters which may be utilized for identification of patients who might further develop TP. Though the objections may arise over the limited role of clinical (Mannheim Peritonitis Index, SPAS II) and laboratory parameters (C-reactive protein) for sufficient diagnosis of TP due to persisting systemic inflammation repeated surgical procedures or intermittent nosocomial infections.[5] In fact, there are conflicting data concerning the value applying such parameters for the detection of TP.[9,12] The Mannheim Peritonitis Index (MPI) developed and first described in 1987 by Linder et al.[13] and validated in several studies for secondary peritonitis.[14,15] represents a scoring system that estimates the severity and prognosis of secondary peritonitis [Table 1]. Recent studies reported encouraging results for the Mannheim Peritonitis Index regarding detection patients at risk for TP.[7,8] It has to be kept in mind that the Mannheim Peritonitis Index is an early (if not the earliest) marker for TP. Its accessibility immediately during the index operation renders the Mannheim Peritonitis Index to a diagnostic tool of high potential to diagnose TP.

Table 1.

The Mannheim Peritonitis Index

SAPS II score[8] initially designed to predict mortality and disease severity of critically ill patients on surgical ICUs has shown a potential to be successfully applied in TP.[16,17]

C-reactive protein constitutes a routine parameter in patients with abdominal infections.[5,12] The main problem of C-reactive protein is the lack of specificity for abdominal infections, and a rise of C-reactive protein during the postoperative period may simply be the result of the operative trauma.[18,19,20,21,22] C-reactive protein or procalcitonin have also rarely been evaluated in the diagnosis of TP.[5,12] There is still a lack of studies addressing the identification of risk factors for patients prone to develop TP. Hence it still remains to have diagnostic markers that could predict the likelihood of a patient to develop TP even at the onset of peritonitis, during the initial operation, or during the first postoperative days.

CONCLUSION

Due to high mortality of TP and often delayed diagnosis, it is crucial to identify patients at risk for developing TP as early as possible, preferably at the initial operation or during the first postoperative days. The Mannheim Peritonitis Index assessed at the initial operation and the time course of C-reactive protein and SAPS II during the first days after initial operation are promising diagnostic candidates for the future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiss G, Steffanie W, Lippert H. Peritonitis: Main reason of severe sepsis in surgical intensive care. Zentralbl Chir. 2007;132:130–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calandra T, Cohen J. The international sepsis forum consensus conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1538–48. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168253.91200.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reemst PH, van Goor H, Goris RJ. SIRS, MODS and tertiary peritonitis. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1996;576:47–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buijk SE, Bruining HA. Future directions in the management of tertiary peritonitis. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1024–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans HL, Raymond DP, Pelletier SJ, Crabtree TD, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG. Diagnosis of intra-abdominal infection in the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:117–21. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans HL, Raymond DP, Pelletier SJ, Crabtree TD, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG. Tertiary peritonitis (recurrent diffuse or localized disease) is not an independent predictor of mortality in surgical patients with intraabdominal infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2001;2:255–63. doi: 10.1089/10962960152813296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panhofer P, Izay B, Riedl M, Ferenc V, Ploder M, Jakesz R, et al. Age, microbiology and prognostic scores help to differentiate between secondary and tertiary peritonitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:265–71. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss G, Meyer F, Lippert H. Infectiological diagnostic problems in tertiary peritonitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathens AB, Rotstein OD, Marshall JC. Tertiary peritonitis: Clinical features of a complex nosocomial infection. World J Surg. 1998;22:158–63. doi: 10.1007/s002689900364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koperna T, Schulz F. Relaparotomy in peritonitis: Prognosis and treatment of patients with persisting intraabdominal infection. World J Surg. 2000;24:32–7. doi: 10.1007/s002689910007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koperna T. Surgical management of severe secondary peritonitis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01369-12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malangoni MA. Evaluation and management of tertiary peritonitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linder MM, Wacha H, Feldmann U, Wesch G, Streifensand RA, Gundlach E. The Mannheim Peritonitis Index. An instrument for the intraoperative prognosis of peritonitis. Chirurg. 1987;58:84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billing A, Frohlich D, Schildberg FW. Prediction of outcome using the Mannheim Peritonitis Index in 2003 patients. Peritonitis Study Group. Br J Surg. 1994;81:209–13. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fugger R, Rogy M, Herbst F, Schemper M, Schulz F. Validation study of the Mannheim Peritonitis Index. Chirurg. 1988;59:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agha A, Bein T, Frohlich D, Hofler S, Krenz D, Jauch KW. “Simplified Acute Physiology Score” (SAPS II) in the assessment of severity of illness in surgical intensive care patients. Chirurg. 2002;73:439–42. doi: 10.1007/s00104-001-0374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.24.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahaba AA, Hagara B, Fall A, Rehak PH, List WF, Metzler H. Procalcitonin for early prediction of survival outcome in postoperative critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:503–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokart D, Merlin M, Sannini A, Brun JP, Delpero JR, Houvenaeghel G, et al. Procalcitonin, interleukin 6 and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): Early markers of postoperative sepsis after major surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:767–73. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reith HB, Mittelkotter U, Debus ES, Kussner C, Thiede A. Procalcitonin in early detection of postoperative complications. Dig Surg. 1998;15:260–5. doi: 10.1159/000018625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg M, Hole A, Johnsen H, Asberg A, Rydning A, Myrvold HE, et al. Reference intervals for procalcitonin and Creactive protein after major abdominal surgery. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2002;62:189–94. doi: 10.1080/003655102317475443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisner M, Tschaikowsky K, Hutzler A, Schick C, Schuttler J. Postoperative plasma concentrations of procalcitonin after different types of surgery. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:680–4. doi: 10.1007/s001340050644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]