Abstract

Background:

Trauma represents a global public health concern with an estimated 5 million deaths annually. Moreover, the incidence of blunt traumatic injuries (BTI) particularly road traffic accidents (RTAs) and workplace-related injuries are rising throughout the world-wide. Objectives: We aimed to review the epidemiology and prevention of BTI, in the Arab Middle East.

Materials and Methods:

A traditional narrative literature review was carried out using PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE search engines. We used the keywords “traumatic injuries”, “blunt” “epidemiology”, “Arab Middle East” between December 1972 and March 2013.

Results:

The most common mechanisms of BTI in our region are RTAs, falls from height, struck by heavy objects and pedestrian motor vehicle trauma crashes. The rate of RTA and occupational injuries are markedly increased in the region due to rapid industrial development, extreme climatic conditions and unfamiliar working environment. However, lack of reliable information on these unintentional injuries is mainly responsible for the underestimation of this trauma burden. This knowledge deficit shields the extent of the problem from policy makers, leading to continued fatalities. These preventable injuries in turn add to the overall financial burden on the society through loss of productivity and greater need of medical and welfare services.

Conclusion:

In the Arab Middle East, population-based studies on the incidence, mechanism of injury, prevention and outcome of BTI are not well-documented. Therefore, region-specific BTI studies would strengthen surveillance to better understand the burden of these injuries in the region.

Keywords: Arab Middle East, blunt traumatic injuries, fall, pedestrians, road traffic accident

INTRODUCTION

Globally, blunt traumatic injuries (BTI) represent a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality. Moreover, the numbers of temporary or permanent disabilities due to BTI are also accounted in millions.[1] Despite better socio-economic conditions and living standards, the incidence of BTI is rising in the Arab Middle Eastern countries. Moreover, most of the countries in this region experiences an over burden on the health care system. The most common mechanism of blunt trauma are road traffic accidents (RTAs), fall from height and struck by the heavy object.[2] Pedestrian motor vehicle trauma crashes (PMVT) are also significantly higher in the regions that mainly involve expatriates from Asian countries.[3] The rate of workplace-related falls is markedly increased in the region due to rapid infrastructure need, harsh working conditions and unfamiliar working environment.[4] According to a World Health Organization (WHO) global survey on road safety, several developing countries have necessary legislative framework for road safety, but unfortunately only 47% have laws relating to major risk factors such as speeding, drink-driving, helmets, seat-belts and child restraints.[5] Further, these laws are generally not widespread in their reach and commitment to enforcement. In fact, in many countries implementation of laws for the prevention of road traffic injuries are unsatisfactory.[5] Moreover, institutional frameworks are inadequately resourced to attain effective outcomes. Another important reason for improper estimates and magnitude of the problem is under-reporting of road traffic fatalities.[5] The quality of information may be influenced by political pressures, competing priorities and accessibility of resources. Data from police records is the only source of road traffic fatalities in around 50% of the countries world-wide.[5] Studies have shown higher levels of under reporting by police and transport department compared with data from the health sector, which highlights the need for an integrated system for improving data quality.[6] Despite the vast impact of pedestrian injuries, less consideration has been observed in the developing countries. Lack of reliable information on pedestrian injuries is one of the main reasons for underestimation of this problem in rapidly developing countries.

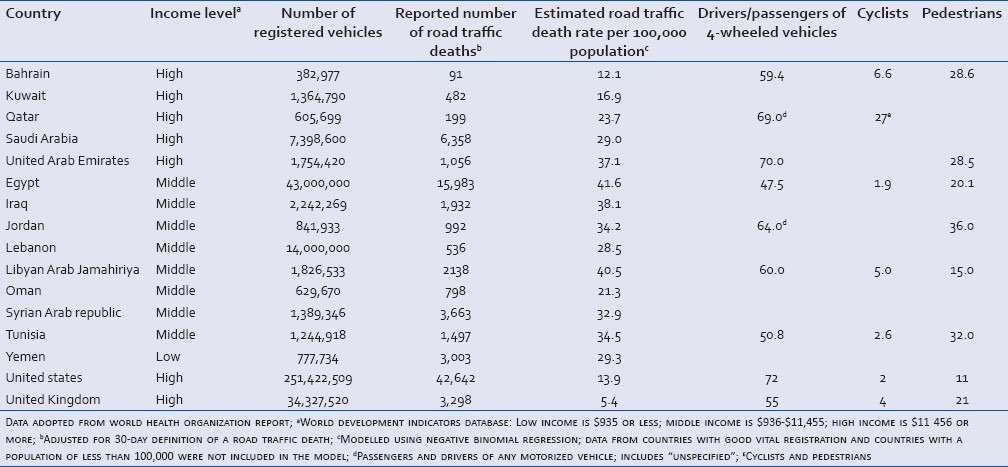

Occupational injuries resulted in sufferings and hardship of workers and their families as physically-active young men are the primary victims of workplace-related injuries. Therefore, these preventable injuries increase the financial burden on society with the loss of productivity and need for medical and welfare services. Health care systems of several middle-income countries of the Gulf are overburdened with traffic-related injuries among pedestrians, passengers of motor vehicles and cyclists.[5,7,8] Libya (40.5), Iraq (38.1), United Arab Emirates (37.1) and Jordan (34.2) has the highest estimated road traffic death rate per 100,000 population in the Arab Middle East. Moreover, Pedestrian injuries are also higher in the Arab Middle Eastern countries in comparison to United States and United Kingdom.

BTI have diverse patterns based on the socio-cultural status and demography. In rapidly developing Middle-Eastern countries such as UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, blunt trauma constituted a significant cause of fatalities among young population.[9,10] Blunt injuries such as RTAs, falls from height and falls of heavy objects are widely reported causes of morbidity and mortality in this region.[2,11] On the other hand, the rapid economic growth has attracted large numbers of expatriate workers from different nationalities which have become the victims of traffic related pedestrian injuries in the Arab Middle East particularly in the rapid developing countries namely Qatar, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.[3] Complex interaction of socio-cultural practices, economic and educational status, politics and large influx of expatriates in the Middle-East make it difficult to estimate the root cause of increasing traumatic injuries.

Unfortunately, little consideration has been given for workplace safety in many developing countries. Also during the last three decades, several armed conflicts occurred in the region. However, most of the published studies are concentrated mainly on the war-related injuries in Iraq, though, the actual data regarding the incidence of BTI in middle-income Gulf countries is still lacking.[5] The key factor for this under reporting and estimation of BTI in the rapidly developing Arab Middle Eastern countries is the lack of relevant literature on BTI. There is considerably limited population-based information available on the incidence, mechanism of injury, outcome and recommendation for prevention for blunt trauma from the Middle-Eastern countries.

Therefore, we have focused on the epidemiology of BTI, traffic injury prevention initiatives and measures for occupational safety and health governance system in the Arab Middle East. Herein, we aim to review the literature to evaluate the epidemiology of traumatic injuries in the Arab Middle East.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A traditional narrative literature review was carried out using PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE search engines. We used the keywords “traumatic injuries,” “blunt,” “epidemiology,” “Arab Middle East” between December 1972 and March 2013. Due to paucity of information regarding this topic all articles were considered for analysis. Medical subject headings (MeSH) terms used were blunt “wounds and injuries” (MeSH terms) OR “wounds” (all fields) AND “injuries” (all fields) OR “wounds and injuries” (all fields) OR “traumatic” (all fields) AND “injury” (all fields) OR “traumatic injury” (all fields). These were limited by the terms (“Arabs” [MeSH terms] OR “Arabs” [all fields] OR “Arab” [all fields]) AND (“Middle East” [MeSH terms] OR (“Middle” [all fields] AND “East” [all fields] OR “middle east” [all fields]) AND (“epidemiology” [Subheading] OR “epidemiology” [all fields] OR “epidemiology” [MeSH terms]). These articles were then included for the review analysis. The criteria for inclusion of articles were based on the epidemiology of BTI in the Arab Middle Eastern region during the mentioned period. Articles written in English which are available on electronic databases and specific institutional sites were included in this study. The articles identified through the search were independently screened by two authors for inclusion, resulting in 20 papers selected for review. Bibliographies of the retrieved references were also used to identify relevant associated articles for cross referencing.

The Middle East is a region that roughly covers the South West Asia and North Africa to include countries extending from Libya on the west to Afghanistan on the East. The “Middle East” refers collectively to the Asian countries of Bahrain, Cyprus, Iran, Iraq, Israel/Palestine, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen and the African country of Egypt. However, this review only focuses on Arab Middle Eastern countries which include Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Palestine, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen and Egypt. The articles on BTI were also searched for specific countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Oman showed 14, 11, 5 and 4 articles, respectively.

RESULTS

The search produced a total of 15,298 articles related to “BTI” and further adding “Middle East” to the search showed 225 articles and subsequent use of “epidemiology” resulted in 149 studies and finally inclusion of “Arab” yielded only 9 articles. Out of 225 articles based on blunt trauma AND Middle East, 205 article were irrelevant to the purpose of this review and were excluded as majority (n = 94) were from non-Arab countries (such as Iran, Israel and Turkey) and 91 were based on non-epidemiological data, 6 studies reported penetrating trauma and 3 studies described blast trauma, 2 articles were published on non-English language and 2 had no abstracts available. Finally, a total of 20 articles were included in this review with the keyword “BTI” in the title or an article regarding “Middle East” in this narrative review. Cross referencing of the of the retrieved references enable us to include a total of 82 references which includes published articles as well as references of data sources on the specific websites.

DISCUSSION

RTAs

Traumatic injuries from RTA are the third most common cause of disabilities world-wide and the second most common cause in the developing nations.[12] It accounts for one-fourth of all blunt injuries, with an annual incidence of mortalities exceeding 1.2 million world-wide.[13,14] Practically, the approach for road safety is region-specific. Also, within a country, the trend varies among the urban and rural populations. Approximately 34% of these unintended injuries are related to RTAs particularly in low and middle income countries.[15] Since late 1980s the numbers of RTA related deaths have increased gradually in the Middle-Eastern and North Africa (MENA) region and in Asia, due to a rapid increase in motor vehicles ownership.[16] Subsequently, RTAs become a major public health issues in these countries.[17,18,19]

In 2002, RTAs have the highest mortality rate (28.3/100,000 population) in Africa, closely followed by the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean (26.4/100,000 population) which also includes Arab Middle Eastern countries.[20] According to WHO/Eastern-Mediterranean Region Office (EMRO), in 2002 the incidence of RTA in the Middle-East was the second highest after Africa.[21,22] Apart from Arab Middle East, countries like Afghanistan, Iran, Morocco, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan are included in the WHO/Eastern-Mediterranean Region. According to the Traffic Fatality and Economic Growth model, there will be a significant increase in road traffic deaths (probable by 68%) in the MENA region by 2020.[23]

The high motorization index (number of registered motor vehicles/1000 individuals) (range: 379-1335) is a considerable risk for traffic-related fatalities among all Eastern Mediterranean countries.[5,24] Many rapidly developing Middle-Eastern countries had a higher incidence of RTA-related fatalities compared to many western countries of relatively similar income levels.[17,18,25]

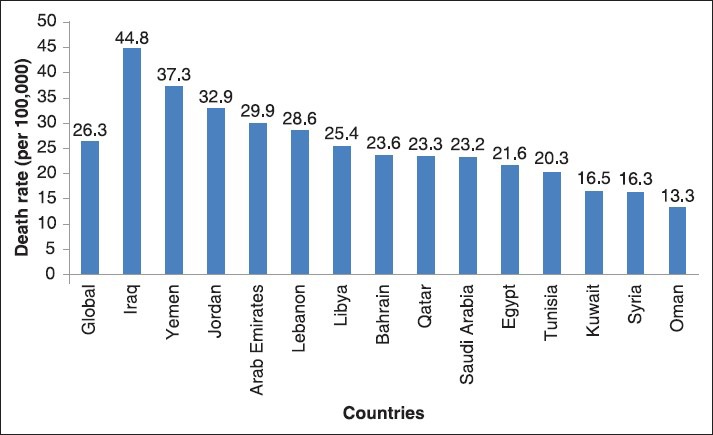

[Figure 1] shows the death rates due to RTA per 100,000 populations in various Middle-Eastern countries, as per world life expectancy data.[26] The death rate ranges from 44.8 in Iraq to 13.3 in Oman.

Figure 1.

The death rates due to road traffic accidents per 100,000 populations in various Arab Middle Eastern Countries[26]

According to recent statistics, Qatar, a small country with rapid booming economy, has the 11th highest motorization rate (number of passenger cars per 1000 inhabitants) (605,699 registered motor vehicles) which is accounted for high fatality rates.[27] Around two-thirds of all injury-related deaths were due to road accidents in Qatar, with 75% of the fatalities in the age group of <50 years.[28]

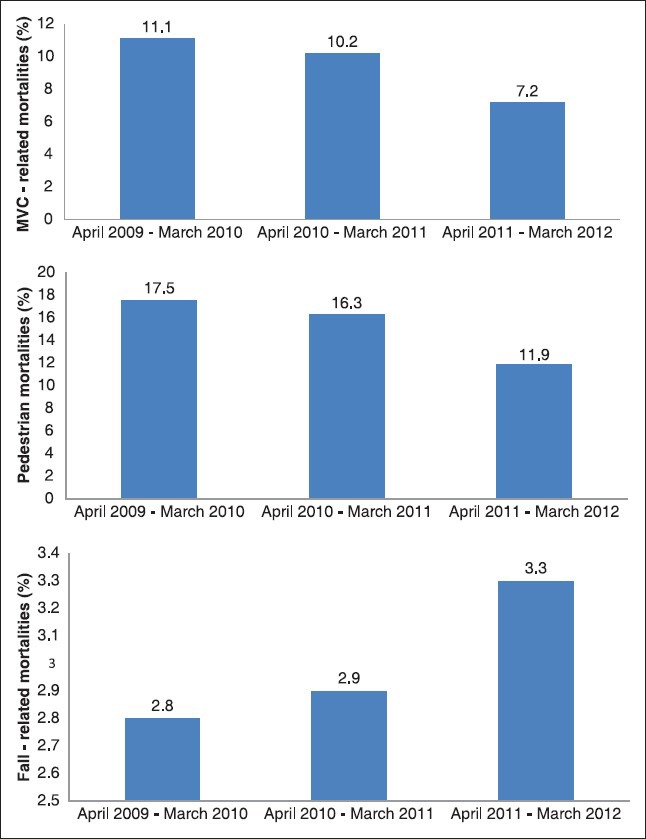

The human factor (behavior) is the major predictable factor for all road accidents world-wide. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration report driver's distraction was mainly responsible for 80% of all road accidents in the US.[29] Earlier reports from the State of Qatar, also observed eating, drinking and the use of mobile phone as the reasons for driver's distraction.[30,31] Another report showed that over speeding and reckless driving were the mainly involved in RTA (57%) cases.[31] Therefore, driver behavior plays an important role in major road crashes. Al-Masaeid[32] in their study reported that young drivers are 1.6-2.5 times more involved in traffic accidents in comparison to the other age groups in Jordan. Other studies from the Middle-East also reported a low frequency of seat belt compliance.[19,33,34,35,36] Over the past years, the trend of RTAs showed some improvement in the region. A decreasing trend of RTAs is also observed in Qatar over last 3 years period, due to strict implementation of road safety measures and dedicated pre-hospital and emergency medical services for trauma patients [Figure 2]. The high incidence of RTA-related injuries needs urgent implementation of road safety measures in the Middle-Eastern countries.[37] Although, authorities in the Middle-East are concerned for controlling RTA since the last decade the objective of effective injury prevention has not been fully attained so far.

Figure 2.

Trend of traffic-related (road traffic accident and pedestrian) and occupational (fall-related) fatalities in Qatar

Traffic-related pedestrians injuries (TPI)

Pedestrians are the most vulnerable group of road users involved in major RTAs, world-wide. In general, socio-cultural practices, education, awareness, reaction-time, vision, vigilance and driving speed, age and expatriates are considerable factors for pedestrian fatalities.[38,39,40] Expatriate workers are more susceptible to road accidents with poor socio-economic conditions, cultural differences, language barriers and exposure of different road driving conventions. Specially, unskilled labors from rural areas are habitual of low-volume traffic and less restrictions on movements which makes them more susceptible for TPI.

Al-Ghamdi[41] found that of the total RTA fatalities reported in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), 29% involved Pedestrians. Further, Al-Shammari et al.[42] reported that more than half (55%) of the pedestrians injured in RTA were expatriates from Asian countries. In United Arab Emirates, of all RTAs involving four wheel drives vehicles and passenger cars in 2000, pedestrians were victimized in 13% cases.[43] The authors found speed violations as a major risk factor for traffic related pedestrian injuries., In Egypt, majority (75%) of RTA victims are pedestrians.[44] Also a campus survey among university students in Egypt showed that 22% of the participants experienced pedestrian injuries during last 6 months.[45] Although, PMVT represents only 5% of total traffic crashes in Jordan, but had higher rates of morbidity (26%) and mortality (34%) causing serious concerns for pedestrian safety.[32] A recent study from Jordan reported high incidence of traffic related injuries (24%) and deaths (32.5%) among pedestrians.[46]

In Qatar, the average injury rate for young pedestrian is higher in comparison to high-income western countries.[47] Bener[48] found pedestrians and motor vehicle passengers (57%) to be the most vulnerable groups for traffic-related injuries in Qatar. A recent study on pedestrian injuries from Qatar showed that of the total hospital admissions during 2007 and 2010, 10.3% represents traffic related pedestrian injuries.[49] According to the Qatar Road Safety survey, pedestrians accounted for >33% of fatalities in RTAs and the incidence pedestrian injuries are increasing [Figure 2].[47] However, the recent traffic statistics (2011) recorded a decline in traffic-related fatalities by 13.3%/100,000 inhabitants of Qatar.[50] A similar trend of pedestrian mortality has been observed in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi during 2011 and 2012, with 21% reduction in mortality by traffic related pedestrian injuries.[51] They also found majority (65%) of the pedestrian who died in RTA were of Asian origin. Despite marked reduction in pedestrian injuries and fatality in some countries, still data is lacking from other Arab Middle Eastern countries regarding the trend of traffic-related pedestrian injuries which need special attention.

Falls from height

Falls continues to be an important source of disabilities and deaths, world-wide. In general, falls are the primary source of serious injuries among children, elderly and industrial workforce, In particular, fall from height is the most frequent cause of workplace related injuries.[52] In rapidly developing countries of Arab Middle East, the majority of fall-related accidents are associated with the construction industry. Over the years, the rate of fall-related accidents is markedly increased due to massive industrial development.[53] Working in exceptionally high-rise buildings and extremes of temperature contributed significantly to the risk of falls. However, it is difficult to analyze the exact incidence of occupational injuries in the construction industry. In many countries, accidents on construction sites are not registered due to lack of awareness and insurance coverage.

According to the Annual Report of Ministry of Health in UAE, fall-related deaths were highest (97%) among expatriates with an age range of 20-64 years.[4] Al-Rubaee and Al-Maniri showed that fall (11.8%) was the second most common cause of occupational injuries in Oman.[54] Since, Qatar will be hosting the next FIFA world cup in 2022, the demand for infrastructure development is enormous which attracts young expatriates to work in the construction industry. A recent study from Qatar, reported falls to be the second most common cause of traumatic brain injury (TBI) among young workers (94%).[11] The incidence of fall-related accidents is proportionately increasing in Qatar over the past few years [Figure 2]. Tuma et al.[53] showed that the incidence of fall injuries in Qatar was 86.7/100,000 workers which has significant financial burden (average $15,735/patient) on health care system. The authors also showed that the majority of workers involved in falls related occupational injuries were expatriates from Nepal, India and Egypt. Because little is known about the incidence and impact of fall-related injuries in Arab Middle Eastern countries, there is an urgent need of information regarding fall related injuries from our region to improve the quality of life and better working conditions.

Fall of heavy objects

Being struck by falling objects is exclusively a construction-site injury. Construction workers face a different kind of health and safety hazards every day in the workplace. Whenever large and heavy objects are being lifted, there is a significant risk of collision and fall. Thereby, falling objects and “struck-bys” are the major source of morbidity and mortality in the construction industry.[55,56] Yousefzadeh Chabok et al.,[57] reported that 2.4% of traumatic spinal injuries were caused by fall of a heavy object. Faeadh[58] found that occupational injuries such as struck by a heavy object or machine was responsible for 4% of head injuries in Iraq. Among all occupational injuries, struck by falling objects (15%) ranked second most common cause of hospital admissions in UAE after falls (51%).[59] Moreover, Barss et al.[59] reported that lack of safety measures were associated with fatal and nonfatal injuries at construction sites in UAE. Parchani et al.,[11] found struck by falling objects to be the third most common cause of head injury among construction workers in Qatar. Another recent study from Qatar found that the rate of injuries by falling objects was 4% with overall mortality of 8.6% at construction sites.[60] To control these unintentional injuries, a National Committee of Occupational Health and Safety has been established in Qatar for strict implementation and assessment of suitable safety measures at construction.

War-related injuries and deaths in the Arab Middle East

In the early 90's Nassoura et al.[61] presented the experience of war-related injuries from a tertiary care center during Lebanon war. The study analyzed 1,500 cases of abdominal trauma, of which 1,314 had high-velocity gunshot wounds, 157 sustained blunt injuries and 29 had stab wounds. The overall mortality rate was 8.7%; of which 9.5% died due to gunshot wounds, 3.4% by stab wounds and 2.5% by blunt trauma. Complications such as hemorrhage (3.7%), sepsis (2.1%) and adult respiratory distress syndrome (1.2%) were the main causes of deaths.[61] Several reports are available on war-related injuries in Iraq. According to a death survey after Iraq war, around 2.5% of the Iraqi population died due to bomb explosion and gunfire during the war period.[62] Feldt et al.[63] analyzed the facial and neck injuries in Iraq war victims. The authors found that the majority of the mild to moderate injuries were due to penetrating (49.1%), blunt (25.7%) and blast (24.2%) injuries with overall mortality of 3.5%. mortality was significantly associated with female gender, pre-hospital intubation, blast injury and treatment at a level IIa center in Iraq.[63] Other studies showed that TBI resulted due to blasts and vehicle crashes represents the frequent source of morbidity among military personnel during Iraq war,[64,65] A study based on the pediatric population in Baghdad, Iraq during war time found gunshot and bomb blasts to be mainly associated with childhood injuries (63% in young children and 83% in older children and adults). Whereas, isolated blunt injuries were less common and was found in 34% of young children and 15% in older children and adults.[66] Hence, majority of war-related injuries in the Arab Middle East were due to penetrating and blast trauma. According to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) on global refugee trends in 2012, around 55% of the world's refugee population belongs to five countries, which are in state of emergency from EMRO. In Iraq about, 746,400 Iraqi lives outside the country after Iraq war. Currently, the Syrian conflict forced 728,500 people to shelter in the nearby countries such as Lebanon and Jordan in 2012 which overburdened the health systems of these host country and raises the serious health issues, Such war related injuries and diseases are unpredictable and are out of the scope of domestic injury prevention and require financial and political support from the leading international authorities.

Major initiatives for injury prevention in the Arab Middle East

Traffic injury prevention

For raising traffic safety standards in Abu Dhabi, the municipality of has recently accomplished many initiatives for in-collaboration with the US.[67] These initiatives include the preparation of manuals for Traffic Safety Audit, Speed Reduction, Traffic Diversions Works and updating roads design to improve road safety as per international standards.[67] The municipality also stepped up the pace of local, regional and global forums for road safety by organizing a series of international conferences and drafted plans to ensure traffic safety around educational institutions, especially school zones.[67]

To overcome the main barriers of road safety in Kuwait, a long-term, comprehensive National Traffic and Transport Strategy (NTTS) was developed in 2009, in collaboration with United Nations Development Program. The NTTS has identified the major obstacles, characteristics and role of each agency for improving road safety. It facilitates institutional reform, human resources development, engineering, law enforcement, community awareness and emergency service for improving public health services in Kuwait.[68]

The Ministry of Interior in Kuwait also launched several road safety initiatives, such as enforcement of cameras at the traffic signals, installation of message signs boards and establishment of Traffic Management System to manage traffic control devices.[69] Furthermore, progress is underway to construct pedestrian over-bridges and convert signalized intersections to roundabouts.[69] To promote public awareness for road safety across the MENA countries “Kuwait Shell” hosted a road safety campaign.[70]

The KSA adopted a world-class “Saher Road system” based on automated traffic control and management system to counter speeding and traffic signal violations through cameras and computerized database. This program showed tangible improvements in driving behavior across the region over the past years.[71]

Egypt participated in the “road safety in 10 countries” project for road safety by controlling speed limits and seat-belt compliance in Cairo and Alexandria. For sustainable road safety and cost-effective solutions, a risk management workshop was held in Cairo (2010) with key participants from the Ministry of Health, Transport and the national police.[72] Apart from road safety and injury prevention, national and international partners also contributed for the development of data system.[73]

In 2008, Jordan introduced a strategic plan for enforcement of strict traffic rules and controlling excessive speeding and traffic violation by traffic police, which showed significant improvement in reducing overall traffic accidents and deaths by 14% and 25.63%, respectively.[32] [Table 1] summarizes vehicles, road traffic deaths and proportion of road users in the Middle East.[73]

Table 1.

Vehicles, road traffic deaths and proportion of road users in the middle east

Similarly in Qatar, strict road safety measures were implemented in the past few years through installation of speed control cameras with higher penalties for traffic violation.[25] Road safety in Qatar continues to be a priority for the National Development Strategy (2011-2016)[74] which focuses on improving road safety through increased public awareness, improved safety measures, strict laws and comprehensive strategy of intra-governmental cooperation for traffic safety. It also focuses on improving pedestrian safety, protecting children and young individuals who are over represented in casualty statistics. The safe-system approach in Qatar will enforces speed limits, strict seatbelt laws and ban of mobile phone while driving.[74] The system will be used to categorize accident prone to improve future planning. It also assess vehicle safety regulations, provisions for pedestrians and cyclists, driver licensing and training systems and penalty standards for traffic violations.[74]

Occupational safety and health governance

Appropriate occupational health and safety measures, particularly focusing construction-related injuries are necessary in the Arab Middle-East.[75,76] The major obstacles in improving occupational health in the region are lack of legislative facilitation, standards, expertise, coordination between the concerned authorities, lack of participation from employers’ organizations and NGOs, insufficient financial and human resources and the lack of educational programs to develop human expertise.[77]

In order to overcome these shortcomings, Gulf Cooperation Council has adopted healthy workplaces initiative using Gulf Strategy for Occupational Health and safety in 2009. Oman has been a pioneer in the region to enforce healthy workplace initiatives among all major corporates.[78]

Furthermore, National Occupational Safety and Health Committee in Qatar has been setup for workplace safety regulations. Establishment of this committee is the first step towards national laws, regulations and standards for occupational health and safety among all working sectors of the country.[74] There is a plan to enforce a centralized interactive database of accidents and diseases which require mandatory reporting of all workplace incidents and accidents. The government also strengthens laws for legal enforcement and accountability of all line managers for occupational safety in key sectors.[74]

Regional recommendations for sustained injury prevention

For sustained injury prevention, active and effective interventions and resource allocation for education and research are at most needed. However, the region is lacking skilled professionals’ capacity building through training and integrated research and collaboration is most important. Also, there is a strong need for population-based information to develop preventive strategies and policies though registries and databases. There is also a need for proper documentation and analysis of RTA and occupational injuries in our region. Detailed regional recommendations are as follows:

Need for integrated research and collaboration

For implementing advanced road safety strategies, a multidimensional approach based on research and collaboration is needed. The focus of research should be on data integration, identification of dangerous road sites, analysis of accidents and improving road designs. There should be a multidisciplinary partnership between health care professionals, traffic and engineering department for data management and analysis. These initiatives have been proposed by the National road safety strategy 2022 in Qatar which is based on “principles of safe system through partnership.”[79]

Need for crash analysis and engineering measures

Data from the identified “Hotspots” should be analyzed according to the road type, traffic flow, pattern of injuries and other environmental factors. So, integrated analysis of database for engineering measures would be helpful in identifying specific patterns and safety issues at accident prone areas.[80]

There is a need to analyze data from major sites and patterns of injuries involved in road accidents for restructuring road design. Knowledge dissemination and raising awareness at the public level plays an important role in development of evidence-based preventive strategies for sustained road safety.[80] Therefore, there is a need of safe-system approach for the road safety in our region.[74]

Sustainable pedestrian safety measures

Reduction of driving speed at accident prone areas is one of the essential factors for pedestrian safety. Improved pedestrian crossings with highly visible, recognizable and uniform pattern will help in preventing PMVT. Adherence to safe driving behavior is also important to enhance pedestrian safety Public awareness campaigns and road surveillance also contributes in improving the overall driving behavior and attitude. Traffic education for children at primary level in schools is also important. Moreover, parents can also contribute to the traffic education of their children at home. The Qatar National Development Strategy (2011-2016) in Qatar is based on the above mentioned directives for pedestrian safety.[74]

Occupational practices and policies

Occupational practices and policies needs to be focused on orientation of expatriate workers for cultural change and appropriate health and safety information. Employees should be educated for safety precautions at workplace and fully aware of the risk of working in high rise buildings. Moreover, safety measure and equipments should be strictly complied while working. At organizational level, reforms in cross-cultural cooperation and accountability should be encouraged to improve occupational health and safety.[81] Furthermore, there is a strong need for multi-lateral strategic plans for proper work-culture orientation and governing safe systems in the workplace by the government authorities.[81,82]

LIMITATIONS OF THIS REVIEW

Though, there are around fourteen Arab countries in the Middle Eastern, only few published articles are available on the current topic from our region. This lack of information could be explained by the fact that all these countries did not use English as their official language and therefore restricting the review to articles written in English is a major limitation. Further, this review did not focus on assault, as majority (92-95%) of blunt injuries cases in our region corresponds to RTAs, pedestrians, falls and fall of a heavy object.[2,49,53] Also, armed conflict and wars in the Gulf region are not considered for injury prevention as it is beyond the scope of this review as war-related injuries are largely unpredictable. Also, the recommendations are generalized for all Arab Middle East countries due to similarity in socio-cultural practices, education level and law enforcement. Another important limitation is the lack of database system to record and analyze the incidence of BTI in most of these countries. Subsequently, if databases are available they suffer inconsistencies in the documentation and missing information which affects data quality and increases the chances of erroneous interpretation. This might results in underestimation of the true incidence of blunt trauma and injury surveillance. These limitations highlighted the need for a mandatory reporting system such as trauma registries, implementation of trauma systems and analysis of the socio-economic factors for evidence-based safety recommendations.

CONCLUSION

There are relatively less population-based studies to support the incidence and prevention of traumatic injuries in the Arab Middle-East. Moreover, lack of education and law enforcement are the main barriers for effective injury surveillance. Therefore, region-specific incidence of BTI would strengthen surveillance to better understand the burden of these injuries in the region. Also, strategic plans, establishment of trauma registries, implementation of trauma systems and analysis of the socio-economic factors are strongly recommended. For the development of regional and national trauma systems, a collaborative approach is needed which includes researchers, health care providers, representatives from the ministry of health and public work and traffic authorities. In addition, public awareness through media and educational programs would substantiate awareness and surveillance of BTI in the region.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. World Health Organization. Injuries and Violence: The Facts. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/key_facts/en/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bener A, Abdul Rahman YS, Abdel Aleem EY, Khalid MK. Trends and characteristics of injuries in the State of Qatar: Hospital-based study. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19:368–72. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.656314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eid HO, Barss P, Adam SH, Torab FC, Lunsjo K, Grivna M, et al. Factors affecting anatomical region of injury, severity, and mortality for road trauma in a high-income developing country: Lessons for prevention. Injury. 2009;40:703–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Ministry of Health; 2006. Preventive Medicine Sector. Annual Report 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Eastern Mediterranean status report on road safety: Call for action. World Health Organization. 2010. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa1045.pdf .

- 6.Derricks HM, Mark PM. The Hague, Netherlands: Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Managementl; 2007. [Last accessed on 2009 Apr 07, Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. IRTAD Special Report. Underreporting of Road Traffic Casualties. Available from: http//www.who.int/roadsafety/publications/irtad_underreporting.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagstaff A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:97–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nantulya VM, Reich MR. Equity dimensions of road traffic injuries in low- and middle-income countries. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10:13–20. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.13.14116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofman K, Primack A, Keusch G, Hrynkow S. Addressing the growing burden of trauma and injury in low- and middle-income countries. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:13–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parchani A, Maull KI, Sheikh N, Sebastian M. Injury prevention implications in an ethnically mixed population: A study of 764 patients with traumatic brain injury. Panam J Trauma Crit Care Emerg Surg. 2012;1:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Publications; 2004. World Health Organization. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Publications; 2003. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2003 - Shaping the Future. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norton R, Hyder AA, Bishai D, et al. Unintentional injuries. In: Jamison D, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Ch. 39. Oxford University Press: 2006. pp. 737–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO; Global Impact. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. 2002. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/world_report/chapter2.pdf .

- 17.Ansari S, Akhdar F, Mandoorah M, Moutaery K. Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 2000;114:37–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Sadig M, Norman JN, Lloyd OL, Romilly P, Bener A. Road traffic accidents in the United Arab Emirates: Trends of morbidity and mortality during 1977-1998. Accid Anal Prev. 2002;34:465–76. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bener A, Abu-Zidan FM, Bensiali AK, Al-Mulla AA, Jadaan KS. Strategy to improve road safety in developing countries. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Magnitude and impact of road traffic injuries. Unit 1. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_traffic/activities/roadsafety_training_manual_unit_1.pdf .

- 21.World Health Organization/EMRO Web site. WHO/EMRO 2006: Commissioning an expert Group for Documenting Injury Data in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/pressreleases/2006/no25.htm .

- 22.World Health Organization/EMRO Web site. WHO/EMRO 2006: WHO Regional Survey on National Situation and Response to Violence and Injury. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/pressreleases/2006/no25.htm .

- 23.Kopits E, Cropper M. Traffic fatalities and economic growth. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37:169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odero W, Garner P, Zwi A. Road traffic injuries in developing countries: A comprehensive review of epidemiological studies. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:445–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mamtani R, Al-Thani MH, Al-Thani AA, Sheikh JI, Lowenfels AB. Motor vehicle injuries in Qatar: Time trends in a rapidly developing Middle Eastern nation. Inj Prev. 2012;18:130–2. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Road traffic accidents: Middle East. World life expectancy data. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/middle-east/road-trafficaccidents-cause-of-death .

- 27.Driving in Qatar. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.keithlane.com/page26.htm .

- 28.Al-Dulimi HH, Abosalah S, Abdulaziz A, Bener AB. Trauma mortality in the state of Qatar, 2006-2007. J Emerg Med Trauma Acute Care. 2010;9:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Press Release; 2006. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. NHTSA, Virgina Tech Transportation Institute Release Findings of Breakthrough Research on Real-World Driver Behaviour, Distraction and Crash Factors. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bener A, Lajunen T, Ozkan T, Haigney D. The effect of mobile phone use on driving style and driving skills. Int J Crashworthiness. 2006;11:459–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgut HR, Bener A, Sidahmed H, Albuz R, Sanya R, Khan WA. Risk factors contributing to road traffic crashes in a fast-developing country: The neglected health problem. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Masaeid HR. Traffic accidents in Jordan. Jordan J Civil Eng. 2009;3:331–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bener A. Road traffic injuries in developing countries: Motor vehicle accidents in the United Arab Emirates: Strategies for prevention. Global Forum for Health Research, the 10/90 Gap in Health Research, Forum 5, Geneva, 9-12 October. 2001:221–2. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jadaan KS, Bener A, Al-Zahrani A. Some aspects of road user behaviour in selected Gulf countries. J Traffic Med. 1992;20:129–35. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klenk G, Kovacs A. Etiology and patterns of facial fractures in the United Arab Emirates. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:78–84. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munk MD, Carboneau DM, Hardan M, Ali FM. Seatbelt use in Qatar in association with severe injuries and death in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:547–52. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00006397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Kharusi W. Update on road traffic crashes: Progress in the Middle East. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2457–64. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregersen NP, Bjurulf P. Young novice drivers: Towards a model of their accident involvement. Accid Anal Prev. 1996;28:229–41. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(95)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Washington, DC: NHTSA; 2008. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24, Last cited on 2010 May 19]. Department of Transportation (US), National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traffic Safety Facts 2008: Pedestrians. Available from: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811163.PDF . [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latifi R, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Zarour A, Parchani A, Abdulrahman H, et al. Traffic related pedestrian injuries amongst expatriate workers in Qatar: A need for cross cultural injury prevention program. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2013 doi: 10.1080/17457300.2013.857693. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Ghamdi AS. Pedestrian-vehicle crashes and analytical techniques for stratified contingency tables. Accid Anal Prev. 2002;34:205–14. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Shammari N, Bendak S, Al-Gadhi S. In-depth analysis of pedestrian crashes in Riyadh. Traffic Inj Prev. 2009;10:552–9. doi: 10.1080/15389580903175313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bener A, Ghaffar A, Azab A, Sankaran-Kutty M, Toth F, Lovasz G. The impact of four-wheel drives on traffic disability and deaths compared to passenger cars. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006;16:257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hisham F. Cairo: Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University; 2006. Injury Statistics and Control Program in Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ibrahim JM, Day H, Hirshon JM, El-Setouhy M. Road risk-perception and pedestrian injuries among students at Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. J Inj Violence Res. 2012;4:65–72. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v4i2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Omari BH, Obaidat ES. Analysis of pedestrian accidents in Irbid City, Jordan. Open Transportation J. 2013;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qatar road safety: 24-25 April. 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.qatarroadsafety.com/about-us.php .

- 48.Bener A. The neglected epidemic: Road traffic accidents in a developing country, State of Qatar. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2005;12:45–7. doi: 10.1080/1745730051233142225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdulrazzaq H, Zarour A, El-Menyar A, Majid M, Al Thani H, Asim M, et al. Pedestrians: The daily underestimated victims on the road. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012 Nov 30; doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.748811. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traffic fatalities decline in the country. 2012. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.infoqat.com/news/moinews/401/Traffic-fatalities-Decline-in-the-Country .

- 51.Hammoudi A, Karani G, Littlewood J. Dubai (UAE): 2nd International Conference on Computational Techniques and Artificial Intelligence (ICCTAI’2013) March 17-18; 2013. Causes of traffic accidents among pedestrians in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong BY. Occupational deaths and injuries in the construction industry. Appl Ergon. 1998;29:355–60. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuma MA, Acerra JR, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Al-Hassani A, Recicar JF, et al. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:3–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Rubaee FR, Al-Maniri A. Work related injuries in an oil field in Oman. Oman Med J. 2011;26:315–8. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jennings D. Safety hazards in construction. [Last accessed on 2013 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www.ehow.com/about_6648240_safety-hazards-construction.html .

- 56.Chen GX, Fosbroke D. Work-related fatal injury risk of construction workers by occupation and cause of death. National Occupational Injury Research Symposium Abstracts. 1997. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/noirs/pdfs/abstracts.pdf .

- 57.Yousefzadeh Chabok S, Safaee M, Alizadeh A, Ahmadi Dafchahi M, Taghinnejadi O, Koochakinejad L. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal injury: A descriptive study. Acta Med Iran. 2010;48:308–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Faeadh MH. Functional outcome of severe closed head injury: A case series study of 50 patients. Tikrit Med J. 2011;17:78–99. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barss P, Addley K, Grivna M, Stanculescu C, Abu-Zidan F. Occupational injury in the United Arab Emirates: Epidemiology and prevention. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;59:493–8. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atique S, Zarour A, Siddiqui T, El-Menyar A, Maull K, Al Thani H, et al. Trauma caused by falling objects at construction sites. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:704–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825472d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nassoura Z, Hajj H, Dajani O, Jabbour N, Ismail M, Tarazi T, et al. Trauma management in a war zone: The Lebanese war experience. J Trauma. 1991;31:1596–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burnham G, Lafta R, Doocy S, Roberts L. Mortality after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: A cross-sectional cluster sample survey. Lancet. 2006;368:1421–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69491-9. Erratum in Lancet. 2009; 373-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feldt BA, Salinas NL, Rasmussen TE, Brennan J. The joint facial and invasive neck trauma (J-FAINT) project, Iraq and Afghanistan 2003-2011. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:403–8. doi: 10.1177/0194599812472874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taber KH, Warden DL, Hurley RA. Blast-related traumatic brain injury: What is known? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:141–5. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riyadh: Ministry of Interior; 1999. Official Statistics: Annual Traffic Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matos RI, Holcomb JB, Callahan C, Spinella PC. Increased mortality rates of young children with traumatic injuries at a US army combat support hospital in Baghdad, Iraq, 2004. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e959–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abu Dhabi Municipality Participates in the UN Ten-Year Traffic Safety Plan. International News-May. 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.alertdriving.com/home/alert-driving-magazine/international/abu-dhabimunicipality-participates-un-ten-year-traffic-safety-plan .

- 68.Jraiw K. National Road and Transport Sector Strategy 2009-2019 for Kuwait Government and UNDP Programme. 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.undp.org/content/dam/kuwait/documents/projectdocuments/Human%20Development/General%20Directorate%20of%20Traffic%20Project%202009-2013%20SIGNED.pdf .

- 69.Current & planned traffic safety measures in the state of Kuwait. Prepared by: Col./Eng. Saadoun Ajeel Al Khaldi Director of Traffic Engineering Dept. MOI — Kuwait. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.abckw.org/ppt/spsc/Safety.ppt .

- 70.Kuwait shell committed to saving lives by promoting road safety measures. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.shell.com/home/content/kwt/aboutshell/media_centre/news_and_media_releases/archive/2009/road_safety_measures_11112009.html .

- 71.Saudi Arabia 2012 OSAC Crime and Safety Report. Road safety. [Last accessed on 2012 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.osac.gov/Pages/ContentReportDetails.aspx?cid = 12215 .

- 72.Global road safety partnership. Road safety in 10 countries. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.grsproadsafety.org/what-we-do/geography/middleeast-north-africa/egypt .

- 73.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 20]. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety: Time for Action. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_traffic/countrywork/egy/en/index.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qatar National Development Strategy, 2011-2016. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.gsdp.gov.qa/gsdp_vision/docs/NDS_EN.pdf .

- 75.Smith GS. Public health approaches to occupational injury prevention: Do they work? Inj Prev. 2001;7(Suppl 1):i3–10. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.suppl_1.i3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barss P, Smith GS, Baker SP, Mohan D. Injury Prevention: An International Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. Occupational injuries; pp. 219–32. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Primary health care and basic occupational health services: Challenges and opportunities: Report on an Intercountry Workshop, Sharm-el-Sheik, Egypt, 12-14 July. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization (WHOs) Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, Annual Report of the Regional Director. 2008. [Last accessed on 2009 Sep 29]. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/rd/annualreports/2008/Chapter1_objective8.htm .

- 79.10-year National Road Strategy launched. [2013 Jan 14, Monday, Last accessed on 2013 Jun 15]. Available from: http://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/qatar/221835-10-year-nationalroad-strategy-launched.html .

- 80. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.thepeninsulaqatar.com/qatar/221835-10-yearnational-road-strategy-launched.html .

- 81.Loo BP, Chow CB, Leung M, Kwong TH, Lai SF, Chau YH. Multidisciplinary efforts toward sustained road safety benefits: Integrating place-based and people-based safety analyses. Inj Prev. 2013;19:58–63. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Integrating Foreign Workers Issues into Qatar Strategies and Policies. December. 2011. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 11]. Available from: http://www.gsdp.gov.qa/portal/page/portal/ppc/PPC_home/PPC_Publications/studies/Integrating%20Foreign%20Workers%20Issues.pdf .