Abstract

Purpose

This article reviews the literature on definitions and issues related to measurement of quality of life in people with diabetes and summarizes reviews of evidence of intervention studies, with a particular focus on interventions targeted for underserved and minority populations.

Methods

An integrative literature review of reviews was conducted on adult diabetes interventions and outcomes. Five electronic databases were searched. Eligible publications were those published between 1999 and 2006 that described outcome measures. Twelve review articles are included.

Results

Review studies were heterogeneous in terms of intervention type, content, participants, setting, and outcome measures. Interventions used variable operational definitions and frequently lacked adequate description; therefore, comparisons of findings proved difficult. A clinical outcome, A1C, was the most frequently assessed, with little inclusion of quality-of-life measures. Several reviews and independent studies did not explicitly consider interventions aimed at the underserved. When quality of life was considered, measures and operational definition of domains were limited.

Conclusions

Understanding the relationship between interventions and resulting outcomes, particularly quality of life, will require attention to operational definitions and better conceptual models. There is an evidence base emerging about important characteristics of effective intervention programs. This evidence base can guide public health and clinical program planners to better understand and make prudent decisions about assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation of interventions for people with complex chronic illnesses such as diabetes.

As the personal, social, and economic burden of diabetes mellitus (DM) continues,1 so does the concern for building the evidence for efficacious and effective primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention strategies. It is important to focus on the outcomes of DM intervention efforts and to individualize diabetes self-management education (DSME).2,3 Community involvement and collaboration can effectively build and deliver culturally centered interventions.4,5 Documenting the effectiveness of interventions requires explicit indicators specific to DSME interventions,3 along the continuum of outcomes categories: immediate (learning), intermediate (behavior change), post intermediate (clinical improvement), and long term (health status improvement).6 Given the important intervention focus on DSME and its related impact on longterm outcomes, the patient’s perceptions and sociocultural context, including quality of life, are also important.

The American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) offers the following working definition for diabetes education:

Diabetes education, also known as diabetes self-management training (DSMT), is a collaborative process through which people with or at risk for diabetes gain the knowledge and skills needed to modify behavior and successfully self-manage the disease and its related conditions. The intervention aims to achieve optimal health status, better quality of life and reduce the need for costly healthcare. Diabetes education focuses on seven self-care behaviors that are essential for improved health status and greater quality of life. The AADE 7 Self-Care Behaviors are: healthy eating, being active, monitoring, taking medication, problem solving, healthy coping, and reducing risks.7

Currently, the success of diabetes interventions is primarily assessed by traditional clinical measures, such as A1C, blood pressure, and blood glucose levels for a variety of reasons. African Americans are at a greater risk for complications related to DM. This article first reviews the definitions and issues related to measuring quality of life in people with diabetes. It then summarizes the published reviews of intervention studies with respect to outcome measures with a special focus on quality-of-life measures and studies that explicitly consider interventions for African Americans.

Background

Improved outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes are related to several complex factors, which operate at many levels: public policy, health system, organizations, and individual provider and patient. Population subgroups, notably African Americans, face greater risks to health status and quality of life.8-11 The public health community is paying considerable attention to health disparities and the role of improved health systems in reducing the burden of DM.

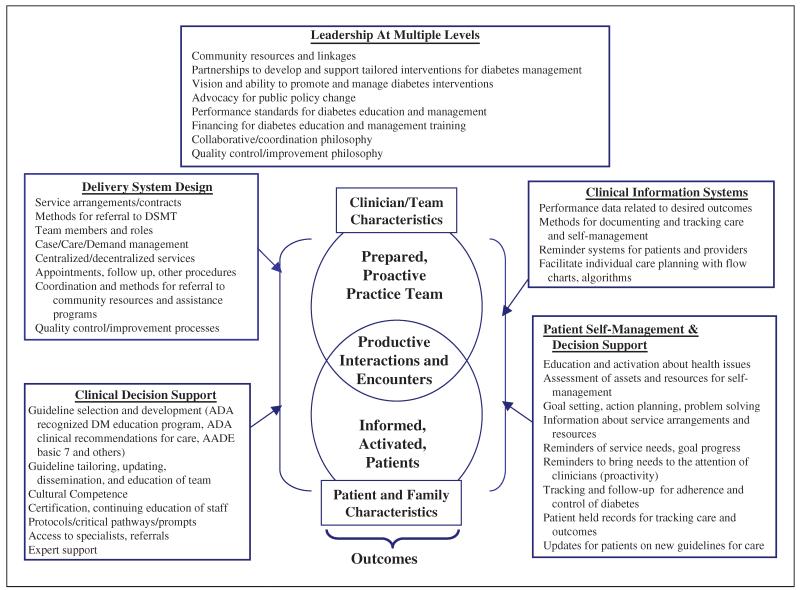

Classically defined, health outcomes are the changed state or condition of an individual as a consequence of medical care over time.12 However, evidence demonstrates that individual and population health status are affected by access to and quality of health care, as well as complex factors at multiple levels, including patient and provider behavior and utilization over time, as noted in Figure 1.13,14 Outcomes can be traditional health status endpoints, such as mortality or morbidity; clinical measures or biological indicators, such as A1C or blood pressure; predisposing and behaviors such as medication compliance; or psychosocial and patient-centered measures such as satisfaction, well-being, or quality of life.

Figure 1.

Strategies to improve outcomes. DSMT, diabetes self-management training; DM, diabetes mellitus; ADA, American Diabetes Association; AADE, American Association of Diabetes Educators. Adapted from Wagner13 and Zapka et al.14

Definition and Measurement of Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is considered a patient-assessed or patient-centered outcome that relates to the individual’s health perceptions, well-being, and functioning.15-17 Moreover, health perceptions reflect the context of cultural and value systems. Various societal and individual determinants influence physical health, psychological state, social relationships, environmental factors, and beliefs.18,19 Several studies report lower HRQOL in people diagnosed with diabetes.20,21 Furthermore, evidence suggests the level of HRQOL is dependent on the presence of comorbidities and the severity of complications and has been significantly correlated with socioeconomic and/or familial barriers.21,22

In the health literature, the terms quality of life (QOL), health-related quality of life, well-being, health status, and satisfaction are used interchangeably.15,16Healthy People conceptualized QOL as reflecting a “general sense of happiness and satisfaction with our lives and environment. General quality of life encompasses all aspects of life, including health, recreation, culture, rights, values, beliefs, aspirations, and the conditions that support a life containing these elements.”23(p10) Overall QOL includes health-related factors and nonmedical phenomena such as personal relationships, employment, spirituality,15 and a sense of well-being.24 QOL is frequently defined as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”19

In comparison, “HRQOL reflects a personal sense of physical and mental health and the ability to react to factors in the physical and social environments.”23 HRQOL is a multidimensional construct of an individual’s subjective appraisal of health and well-being involving physical, psychological, and social functioning.25 HRQOL includes health perception of risk and conditions such as social support, as well as socioeconomic and functional status.10 The literature, although discordant, concedes that HRQOL is patient centered and is grounded in one’s reality. Because HRQOL is a measure of subjective health status and quality of life, health care providers are encouraged to consider HRQOL as a priority outcome, in addition to traditional physiologic and functional indicators.

Disease-specific instruments are designed to be used in a specific patient group, sensitive to treatment and natural history, and are more responsive to changes in health.18,26 Important contributions have been made to identify and understand available diabetes-specific measures of HRQOL. Garratt and colleagues18 reviewed available instruments, summarized the psychometric evidence, and made recommendations for their use. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to review all the findings of Garratt and colleagues’ extensive work, Table 1 reports important dimensions of existing instruments that reflect the personal and social outcomes important to living with diabetes.

Table 1. Instrument Dimensions (Number of Items).

| Appraisal of Diabetes Scale |

Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality of Life |

Diabetes Health Profilea |

Diabetes Impact Measurement Scales |

Diabetes Quality-of-Life Measure |

Diabetes-Specific Quality-of-Life Scale |

Diabetes-39 | Questionnaire on Stress in Patient With Diabetes-R |

Well-Being Enquiry for Diabetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single index (7) |

Single index (13) |

Psychological distress (14) |

Well-being (11) | Worries about future effectsof diabetes (4) |

Worries about future (5) |

Anxiety and worry (4) |

Depression/fear of future (6) |

Serenity (10) |

| Barriers to activity (13) |

Diabetes-related morale (11) |

Worries about social/vocational issues (7) |

Social relations (11) |

Social and peer burden(5) |

Leisure time (4) | Discomfort (10) | ||

| Disinhibited eating (5) |

Nonspecific symptoms (11) |

Impact of treatment (20) |

Leisure time flexibility (6) |

Sexual functioning (3) |

Partner (6) | Impact (20) | ||

| Specific symptoms (6) |

Satisfaction with treatment (15) |

Daily hassles (4) | Energy and mobility (15) |

Work (6) | ||||

| Diet restrictions (5) | Treatment regimen/diet (9) |

|||||||

| Physical complaints (8) |

Diabetes control (12) |

Physical complaints (6) |

||||||

| Treatment satisfaction (10) |

Hypoglycemia (4) Doctor-patient relationship (4) |

The number of items for the Diabetes Health Profile refers to the DHP-1. The DHP-18 has 6, 7, and 5 items for the psychological distress, barriers to activity, and disinhibited eating dimensions, respectively. Table 2 in Garratt AM, Schmidt L, Fitzpatrick R. Patient-assessed health outcome measures for diabetes: a structured review. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:1-11. Reprinted here with permission.

Methods

To determine the state of evidence of HRQOL as a measured outcome in interventions designed specifically for adults with type 2 diabetes, the following were searched (1996-2006) for systematic or critical reviews and meta-analysis articles: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO databases. Inclusion criteria included English-language and review articles reported to include patient outcomes published between 1999 and 2006. The subject headings used for search included disease management, case management, care management, community, health system, self-management, self-management education, blacks, African Americans, health-related quality of life, quality of life, intervention, and outcomes, all in association with type 2 diabetes. In addition, selected bibliographic references and diabetes journals of relevance were searched by hand. Twelve review articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this integrative review.

The analyses included review of criteria for inclusion in the review, the number and design of studies included, intervention description (components, content, and setting), and the impact, process, and outcomes assessed. This study includes comments about QOL instruments and consideration of minority and disadvantaged populations.

Findings

Table 2 reports the key analysis points for each review article, listed in alphabetical order by first author. The reviews covered studies conducted between 1966 and 2006, although the reviews were published between 1999 and 2006.

Table 2. Summary of Review Articles.

| Period and Methods | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria N = Number of Studies |

Intervention | Impact, Process, and Outcomes Assessed |

Notes/Comments Re: QOL in Minority and Disadvantaged Populations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:26-35. | ||||

| 1987-2001: MEDLINE supplemented by review of bibliographies from identified studies and reviews |

Included English-language RCTs or quasi- experimental studies with comparison group; DSME intervention delivered to an underserved/ disadvantaged group or community. |

Component DSME, group and individual sessions, informational mailings, media campaign, peer support, home visits, unstructured sessions, videotapes, handouts, monthly calls from nurse |

RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework used to compare and evaluate studies Physiological GHb, cholesterol, BP, weight, FBG, BMI, body composition, glucose tolerance and symptoms |

Studies were conducted with explicit focus on minority and disadvantaged populations. |

| A summary methodologic rating of 0 to 9 was calculated. Scores ranged from 2 to 8, with 4 studies receiving a score of 7 or more. |

||||

| Excluded descriptive reports and studies without comparison group. N = 10 studies |

Content DM knowledge, early detection, exercise, nutrition, lifestyles, history and culture (Pima Indian community), compliance, access to primary care Setting Delivered in community centers, community, hospital clinic, and by telephone |

Behavioral Diet, physical activity, smoking, EtOH use Knowledge DM self-management (nutrition, general DM), changes in medication regime Other Cost to provide intervention Psychosocial Depression, social support, self-efficacy, and QOL QOL: 3 of 10 studies |

Authors emphasize that DSME interventions for underserved populations should explicitly address social-contextual issues. |

|

| Authors suggest that interventions designed to be proactive, such as telephone follow-up and behaviorally focused DSME interventions incorporated within the primary care visits, have successful levels of implementation. |

||||

| QOL instruments: Daniel et al, 1999-not reported; Glasgow et al, 1992-assessed diabetes- specific QOL with a modified DCCT DQOL scale, no between-group statistical significance observed; Weinberger et al, 1995-measured HRQOL using the SF-36; statistical significance not observed. |

||||

| Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Brown A, Pichert JW, Elasy TA. Diabetes patient education: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:97-105. | ||||

| 1990-12/2000: MEDLINE, CINAHL, HealthSTAR, ERIC, Science Citation Index, PsyclNFO, CRISP, and AADE database |

Included English-language RCTs using educational, including nonpharmacological, intervention intended to improve patients’ health status (physical, intellectual, and/or psychosocial), interventions for adults, and reporting pre- and postintervention A1C values (at least 12 weeks postintervention). N = 28 studies |

Elasy’s taxonomy used to categorize educational interventions and assess relationship between specific variables within the interventions and metabolic control. |

Physiological A1C Psychosocial HRQOL/QOL: not reported |

Authors report only A1C measures, noting other important outcomes were neither uniformly available nor uniformly measured in the literature. |

|

Component Didactic, negotiated goal setting; goal setting; situational problem solving; cognitive reframing; and other unspecified |

Authors used meta-regression to identify “components” of the educational intervention that best explained variance in metabolic control. Meta-analysis supports the notion that patient education improves glycemic control. |

|||

|

Content Diet, exercise, self- monitoring blood glucose, basic diabetes knowledge, medication adherence, psychosocial, and other unspecified |

The authors examined the impact of the number of “episodes” as well as the duration, and neither of these dose-related indicators predicted (was an indicator) an intervention’s success or failure. |

|||

|

Setting No reported setting. Referred solely to the number of recipients |

Authors note that work would have been enhanced with the inclusion of behavioral outcomes. |

|||

| Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:488-501. | ||||

| 1966-1999: MEDLINE; Cochrane Collaboration database (1990-1999); references from experts, colleagues, previous meta-analyses, and review articles |

Included published trials randomized by clinician and/or patient, sample size ≥ 10, English language; educational, counseling, or behavioral interventions aimed at long-term self-care behavior. |

Components Individual and group counseling, instruction packets and audiovisual materials, telephone outreach; clinician prompting, clinician education, computer programs |

Physiological FBG, total glycohemoglobin, hemoglobin A1 or hemoglobin A1C, body weight or BMI, blood pressure, and lipids Psychosocial QOL: not reported |

Authors assigned and categorized methodologic quality scores. Scores were grouped into low (<0.65), moderate (0.65- 0.79), and high (≥ 0.80), with 5 studies receiving a quality rating of high. |

| Excluded published abstracts, type 1, drug interventions, and studies evaluating short-term effects. N = 18 studies |

Content Patient-diet, exercise, medication regime changes or adherence, BGSM, and foot care |

Authors found that compared with controls, most intervention groups produced a decline in glycohemoglobin. Furthermore, group and individual counseling produced similar effects. |

||

| Providers-methods to increase patient involvement, DM pathophysiology, complications, DM education, urine testing, and treatment/regimen adherence Setting Outpatient clinic (96%) |

Authors note that very few studies reported including African American or Hispanic individuals. |

|||

| Authors cite few studies that have evaluated culturally sensitive interventions for African Americans and other ethnic minority populations, an issue that should be addressed. |

||||

| Authors note lack of QOL measurement as a limitation. |

||||

| Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, Willson K. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29: 1675-1688. | ||||

| 1986-2004: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Health STAR, Cochrane Library, Sociological Abstracts, Social Science Citation Index, and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts |

Included RCT, CT, and before-and-after studies with a control group; studies aimed toward low SES or ethnic/racial minority or socially disadvantaged adults with type 1 and 2 DM. Included studies of any language that measured self-management, provider management, or clinical outcomes. |

Elasy’s intervention taxonomy used to describe scope and components of the interventions. |

Physiologic FBG.A1C, BP, BMI, lipids, mortality, DM complications Patient behavior Glucose monitoring, diet and exercise, medication adherence and self- adjustment, scheduling and/or attending scheduled medical appointments Provider behavior Management: diagnostic testing, prescribing, referrals, educational and behavioral counseling Psychosocial QOL: not reported |

Studies focused on those groups with low SES or belonging to an ethno- racial minority. To evaluate methodological quality, the authors used an evaluation method to identify specific intervention features that are associated with successful or unsuccessful outcomes: (1) target of intervention, (2) intervention design, (3) setting, (4) delivery, and (5) intensity and duration. |

|

Components Individualized assessment and goal setting, individual educational counseling, DSME, reminder cards, videotapes, support groups, case management, evidenced-based guidelines, community health workers/peer educators, group visits, treatment algorithms | ||||

| Excluded: age-specific, gestational DM studies; studies that only reported hospital process of care measures; and those not specifying which socially disadvantaged group. N = 11 studies |

||||

|

Content DM knowledge, self-care, symptoms and treatment, exercise, nutrition, foot care, lifestyle, monitoring; clinician-focused evaluation and management of glycemic control, associated comorbidities and complications |

Authors suggest that cultural tailoring, use of community educators or lay educators, one-on-one interventions, individualized assessment/reassessment, use of treatment algorithms, behavioral interventions, and patient feedback are all consistent with positive rate differences found in multiple studies. |

|||

|

Setting Primary care practice sites, hospitals, community- based clinics, community facilities (centers, churches), and telephone |

High-intensity (>10 contacts) and delivery over a long time frame (≥ 6 months) were also associated with success intervention in disadvantaged groups. |

|||

| Loveman E, Royle P, Waugh N. Specialist nurses in diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003286. | ||||

| 1966-11/2002: MEDLINE, Cochrane library, EMBASE, CINAHL, British Nursing Index, Royal College of Nursing Index, HealthSTAR, BIOSIS, PsyclNFO, Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index; hand-searched relevant journals and conference proceedings (1990-2001), reference lists, National Research register, Early Warning system and Current Controlled Trials registries |

Included randomized controlled and controlled clinical trials designed to test effects of DNS/NCM interventions, trial duration 6 months. |

Components DNS plus routine care versus routine care, automated calls with structured messages, treatment regime alterations led by DNS/NCM, treatment recommendations to PCP by DNS/NCM, and care coordination within primary care system Content Goal setting and self-care Setting Hospital, outpatient clinic, primary care system, and community |

Physiological All trials used A1C as endpoint; short-term complications (hypoglycemic episodes, hyperglycemic incidents) |

Methodologic quality of studies was assessed using factors included in Schulz and Jadad’s quality criteria: minimization of selection, attrition, and detection bias. Studies were then subdivided in the following categories: low, moderate, and high risk of bias. |

| Excluded studies with no control group, group education, no prespecified outcomes, other team members other than DNS/NCM involved delivering intervention, nurses not able to adjust treatments. N = 6 studies |

Other Emergency room visits, hospitalizations Psychosocial Quality of life QOL: 1 of 6 studies with no data presented |

|||

|

Other Prespecified outcomes established for this review but not included and/or reported in trials: long-term complications (retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy), mortality, BMI, costs, and adverse effects |

Authors noted that the quality of trials was mostly not good, making it difficult to assess the implications for practice. Future research suggestions include international observational studies to identify roles and time allocations; qualitative studies and RCTs of specialist nurse intervention. |

|||

| Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Venkat Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561-587. | ||||

| 1/1980-12/1999: MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL, restricted to RCTs, hand-searched several relevant journals; abstracts and dissertations were excluded |

Included English-language RCTs examining the effectiveness of self- management training, all or most subjects with type 2 DM, age >18, multicomponent interventions included (if educational component evaluated separately). Excluded children. N = 72 studies |

Components Chart reminders, group and individual sessions, written information, videos, didactic education, individual sessions based on patient’s priorities, home visits, computer knowledge assessment program, feedback, behavior modification, contracts, demonstrations, food logs, nutrition goals, interactive computer, culturally appropriate flashcards, pharmacist, nursing students, dietitian , lay health worker, nurse-led sessions, psychologist-led group sessions, patient-led education, and self-study course |

Physiological Weight, lipids, blood pressure, glycemic control Behavioral Dietary, physical activity, self-care skills Knowledge Diabetes Other Economic measures; health care utilization Psychosocial Attitudes, problem solving, anxiety levels, quality of life QOL: yes, in 5 studies Kaplan 1987-increase in QOL at 18 months for lifestyle intervention (intensive counseling on diet + physical activity). Gilden 1992-increase in QOL at 2 years follow-up for coping skills intervention (6 weekly sessions +18 monthly support group sessions). |

Authors qualitatively summarized outcomes to generate hypotheses, categorize variables for quantitative syntheses, and illustrate the vast heterogeneity of methods and outcomes in the included literature. |

| Notably, the authors emphasize limited literature measuring QOL and long-term clinical outcomes. Authors advocate for a more holistic view of patients, including that QOL outcomes take precedence in future research and more diverse study populations. |

||||

| Content | Three studies (deWeerdt, Glasgow, Trento) considered “brief interventions” with no significant difference between intervention and control groups. |

|||

| Physical activity, diet, nutrition, SMBG, weight loss, barriers, social support, foot care, general DM knowledge, self-adjustment of insulin, goal setting, problem solving, stress management, patient empowerment, self- control, self-management |

||||

|

Setting Not specifically identified in the review; described as heterogeneous |

||||

| Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159-1171. | ||||

| 1980-1999: MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL; manual search of relevant journals, and experts were consulted for citations |

Included English-language RCTs, DSME interventions, and other interventions when delivered in combination with DSME (if effect of DSME could be examined separately). |

Components Didactic or collaborative DSME, individual and group education, support groups, home visits, dietician, flashcards by lay health workers, meal demonstration, feedback, telephone follow-up, psychologist-led group sessions, weight loss program, empowerment techniques, computer- assisted knowledge assessment and instruction |

Physiological GHb, HbA1, HbA1c Psychosocial QOL: not identified as a key outcome of this review |

Meta-regression indicates no significant interactions except total contact. In 15 studies, GHb measurements were reduced for every hour of additional contact, which approximates 23.6 hours of contact between an educator and patient to achieve a 1% reduction; brief intervention appears to be less effective. |

| Excluded abstracts and dissertations. N = 31 studies |

||||

|

Content Diet, physical activity, SMBG or urine glucose, foot care, coping, self-efficacy, identifying and preventing complications, goal setting, and modeling Setting Clinic, home, and senior center |

Authors suggest that psychosocial mediators, cultural relevancy, and health care system structure and primary care linkage may account for the heterogeneity in outcomes. |

|||

| Authors stress that further research to identify predicators and correlates needs to focus on psychosocial attributes, social support, and problem-solving skills. |

||||

| Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22(suppl 4):15-38. | ||||

| 1966-12/2000: MEDLINE, ERIC, CINAHL, HealthSTAR, Chronic Disease Prevention database (health promotion and education subfile), Combined Health Information Database, diabetes, health promotion and education subfile), journals hand- searched, reference list of included articles and consultation with team experts for relevant citations |

Included published comparative study designs, English language, conducted in established market economies as defined by the World Bank, studies with primary investigation of disease (as defined by review team) and case management intervention, reported information on 1 or more outcomes of interest preselected by review team. |

Components Disease or case management along with DSME, telemedicine support, insulin adjustment algorithms, group support, visit reminders, hospital discharge assessment and follow-up Content Not applicable or not specified Setting Managed care organizations and community clinics |

Physiological A1C, weight, BMI, BP, and lipids Behavioral SMBG, patient health care utilization; provider screening, monitoring and treatment): A1C, lipids, dilated eye exams, foot exams, proteinuria Other Health care system: health insurance, provision of services, health care utilization (admissions, outpatient visits, length of stay), public health services, economic outcomes Psychosocial Self-efficacy, patient satisfaction, quality of life |

Authors note research gaps in the areas of intervention effectiveness on long-term health and QOL outcomes, as well as diverse populations and settings. |

| QOL Instrument: Peters et al (1998) used the SF-36 with 2 (unspecified) diabetes- specific questions added. | ||||

| Excluded: studies characterized as limited quality based on the number of threats to validity, dissertations, and abstracts. N = 42 studies |

QOL: Assessed in 2 of 42 studies (1 in adults and 1 in children); adult cohort study reported relative change of +4.7% between groups. |

|||

| Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, Wagner EH, Eijk Van JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1821-1833. | ||||

| 1966-2000: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, EPOC, and Cochrane clinical trial registries (1999); reference list of selected articles was reviewed |

Included studies of effectiveness of interventions to improve process of care or patient outcomes among type 1 or type 2 that had (1) randomized or quasi- experimental trials, (2) interrupted time series with defined interventions and a minimum of 3 before-and-after time points, (3) nonrandomized studies with a second controlled site, and (4) predetermined measures of patient outcomes or the process of health care. |

Components Professional (education, reminders, audit, and feedback); organizational (role revision, changes in medical record systems; patient education, learner-centered counseling, telephone follow-up for missed appointments); financial (fee for services and grants) or multistrategy Content Provider-guidelines Patient-problem solving and decision making Setting Primary care, outpatient, and community |

Physiological Glycemic control, BP, cholesterol, BMI, weight, microvascular and/or macrovascular complications, albumin, creatinine Behavioral Patient attendance, provider process measures: glycemic control, BP, weight, microvascular complications, cholesterol, visits, education, health survey, compliance care providers, albumin, urine protein, creatinine, hospitalizations |

The authors note that complex professional interventions improved the process of care, but patient outcomes were rarely assessed, making it less clear to evaluate the impact. Furthermore, the authors emphasize that measuring both process and patient outcomes lead to better understanding of how to improve quality of care. |

| Excluded study interventions classified as only patient oriented. N = 41 studies |

Other Hospitalizations, health care system process measures: glycemic control, BP, weight, cholesterol, visits, education, microvascular complications Psychosocial Well-being, quality of life QOL: yes, but limited 3 of 41 (2 QOL and 1 well-being) studies. QOL outcomes showed no effect in 2 professional and organizational interventions; well-being reported as positive effect in 1 education intervention. |

|||

| Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, Wintz RL, Mangione CM. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American, or Latino adults. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:467-479. | ||||

| 01/1995-12/2000: MEDLINE, HealthSTAR, EMBASE, PsyclNFO, Ageline, and Sociological abstracts |

Included English-language published intervention studies that described intervention aimed at changing knowledge, beliefs or behavior; targeted 1 or more of the following: age >55 years, African American or Latino adults with DM; and measure at least 1 of the preidentified outcomes: glycemic control, diabete- srelated symptoms, or quality of life. N = 12 studies |

Components Group education plus exercise class; group sessions led by physician, nurse, or dietitian; didactic DM education alone or in combination with support groups, individual counseling, 1-to-1 DM education, bicultural community health worker liaison, nutritionist, weekly pharmacist appointments, grocery store tour, follow-up phone calls, physician education |

Physiological Glycemic control and diabetes-related symptoms (established as an outcome of interest by review authors but not assessed in any of the 12 included studies) Psychosocial Quality of life HRQOL/QOL In 5 of 12 studies: 4 of 8 RCTs and 1 of 4 pre/post designs; 1 RCT reported statistically significant improved QOL in the intervention arm (78 points vs 71 points); |

Authors were unable to summarize the effect of self-care interventions on quality of life because of the heterogeneity of QOL instruments. |

| The authors suggest that age- and culture-specific interventions be designed for clinical trials. | ||||

|

Content Exercise, nutrition, goal setting, “standard DM education curriculum,” others unspecified/unclear Setting Noted as urban or rural |

1 pre/post design reported improved mean scores on the QOL instrument, with no mean change in A1C at end of intervention. |

|||

| Steed L, Cooke D, Newman S. A systematic review of psychosocial outcomes following education, self-management and psychological interventions in diabetes mellitus. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:5-15. | ||||

| 1980-2001: EMBASE, MEDLINE, Psyclit; hand search of reference list of reviews and retrieved papers |

Included pre/post or controlled trial design studies published in English-language peer- reviewed journals, adults with type 1 or 2 DM, provision of DMSE or psychological intervention and assessed either QOL or psychological well- being. |

Components Classified as education, self- management, or psychological biofeedback. Content General education, diet, meal planning, goal setting, reinforcement, modeling, reward systems, problem solving, exercise sessions, behavior change maintenance, relaxation, communication skills, and social support Professional or layperson- led discussion groups Setting Not reported |

Psychosocial Overall psychological well- being, depression, anxiety, or emotional adjustment and QOL HRQOUQOL Ten studies used a generic measure, 9 used a diabetes-specific measure, 1 used both, and 5 studies used an overall psychological well-being measure. |

This review did not speak to issues related to minority or disadvantaged groups. The authors were unable to examine the efficacy of different intervention components; noted as the original aim of the review, multiple components in single studies and the overlap between components in different intervention categories hindered these attempts. Self-management interventions had beneficial impact on QOL. None of the included studies using psychological |

| Excluded interventions that provided only diet or exercise or intensive insulin regimens. N = 36 studies |

Generic QOL measures: 2 of 9 studies showed improvement relative to control; DM-specific QOL measures: 6 of 9 found improvement. Overall psychological well- being: 1 of 5 reported significant improvemen. Global and disease-specific QOL were not assessed in any of the psychological interventions. |

|||

| Authors suggest that future research should use diabetes-specific studies measures within larger controlled trials. |

||||

| QOL Instrument: SF-36 and DQOL were the most frequently used generic and diabetes-specific instruments, respectively. |

||||

| van Dam HA, van der Horst F, van den Borne B, Ryckman R, Crebolder H. Provider-patient interaction in diabetes care: Effects on patient self-care and outcomes: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:17-28. | ||||

| 1980-10/2001: MEDLINE Advanced, EMBASE, PsycIit/PsycINFO, and The Cochrane Library |

Included English-language RCTs and quasi- experimental studies testing the effects of modification of patient- provider interaction and provider consulting style on DM self-care and outcomes. |

Component Provider training, questionnaire prompts, feedback reports; patient- automated telephone calls, nurse telephone feedback, individual education, empowerment group ed. sessions, group consultations with doctor, and individual consultation with standard DM education |

Physiological BP, lipids, BMI, GlyHb, general health, mortality Behavioral Health behavior Knowledge DM knowledge Psychosocial Satisfaction, well-being, mental health, self- efficacy, DM-specific QOL scores |

Methodological quality was assessed using a modified version of the Van Tulder criteria list; the authors include a table of the criteria. Nineteen items (questions) are categorized into the following categories: patient selection, interventions, outcome measurements, and statistics. The mean quality score was 17.3 out of 19 total points. |

| Excluded non-type 2 DM patients, case, case control, and nonexperimental studies. N = 8 studies |

||||

|

Content Provider-behavioral change, communications, patient- centered consulting, guidelines; patient-diet, self-care, problem solving/barriers, decision making Setting General practice or hospital outpatient |

Patient: communication, interaction, lifestyle, perception of care, functional, attitudes Provider: beliefs, attitudes, and behavior change; adherence to guidelines, time spent with patient |

Authors emphasize a shift from the traditional medical model and toward a patient empowerment model with shared decision making. |

||

|

HRQOUQOL In 2 of 8 studies: 1 with no change in HRQOL scores and 1 with “better” QOL. |

Authors note they found no evidence that the 3 most promising studies have ever been replicated among diverse patient populations or different care settings, thus causing alarm. |

|||

RCT, randomized controlled trial; DSME, diabetes self-management education; DM, diabetes mellitus; BP, blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; BMI, body mass index; QOL, quality of life; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; DQOL, diabetes quality of life; DCCT, Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group; SES, socioeconomic status; PCP, primary care provider; CT, controlled trial; BGSM, blood glucose self-monitoring; DNS/NCM, diabetes nurse specialist/nurse case manager; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Included Review Articles

Variable criteria were considered within each individual review. For example, some included only randomized trials (RCTs),27-32 whereas others included RCT, quasiexperimental, and/or other comparative design methods.33-37 Exclusion criteria also varied considerably across reviews. For example, some studies were excluded because they evaluated short-term effects32 or included only patient interventions.34

Intervention Type and Content

Numerous intervention approaches in a variety of settings were reported33,38 and included delivery by lay leaders and professionals from diverse health care disciplines.30,31 Many interventions included multiple components or strategies. Intervention content was loosely defined and, again, was broad and varied within each review.29 Content ranged from being unspecified to diet, nutrition, goal setting, problem solving, or simply described as “standard diabetes education curriculum.”

Terms such as disease management and case management are widely used, and their operational definitions are exceptionally broad and variable.35,37 The goal of disease management is improved short- and long-term health and/or economic outcomes. In particular, disease management interventions have been promoted, especially for costly, chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus. For the included studies, settings were urban centers of managed care organizations and outpatient and community health clinics. A range of organizational, professional, and patient intervention components and strategies was included and supported multisystem approaches, which could lead to improvements in patient outcomes as well as process of care.35

Case management, one component of a multisystem collaborative approach, delivered in conjunction with disease management, can serve an important role for people at high risk for adverse outcomes and excess health care utilization. Furthermore, assessment, planning, linking, monitoring, advocacy, and outreach, described as essential core functions of case management, are complementary with the chronic care model (CCM).39 Yet, multicomponent approaches incorporating both disease and case management have been shown to improve outcomes as well as the process of care.30,34,35 The evidence suggests that DSME was routinely delivered across disease management and case management interventions. Moreover, integrating DSME across interventions could potentially help to costeffectively optimize outcomes, such as metabolic control and quality of life, and prevent complications.40,41

Impact, Process, and Outcomes Assessed

Seven of the review articles included in this review primarily focused on DSME interventions,27-29,31-33,36 specifically, the effect of DSME interventions on multiple physiological, psychological, behavioral, and knowledge processes and outcomes27,28,33 and, to a lesser extent, HRQOL.29,36 Notably, Steed and colleagues36 completed a systematic review of psychological outcomes (eg, psychological well-being and QOL) in 36 studies. They found that self-management interventions had more positive impact than educational interventions where patients received information only. Nine of the 36 studies reviewed by Steed et al used diabetes-specific QOL instruments; of these, 5 used the diabetes quality of life (DQOL).42 Six of the 9 trials found QOL improvement postintervention, with no significant difference reported in 3 of the studies. Overall, 6 trials found QOL improvement postintervention. However, no significant difference was reported in 3 of the 5 studies using the DQOL.

Outcome measures varied substantially across studies, making it difficult to compare results across interventions, and many studies lacked sufficient detail for replication. Even when glycemic control was assessed, a variety of different methods and reference values was used.32,34 Although outcomes for diabetes education research have historically focused on knowledge and glycemic control (A1C),43,44 researchers and clinicians generally agree that DSME should be integrated across multiple intervention strategies and encompass behavioral approaches to improve self-management outcomes.44 Also, several RCTs have demonstrated the value of blood pressure and other outcome variables. In addition, the outcomes of disease management, case management, and/or multisystem approaches to diabetes interventions are more often physiologic measures, as evidenced in Table 2.

The reviews identified few studies focusing on African Americans, particularly older African Americans. For example, in a review of self-care interventions designed to improve glycemic control or QOL in older, African American, or Latino adults, only 1 study among African Americans (n = 39) examined QOL.29

Discussion and Recommendations

Several key observations emerged from this review of reviews. Statements about the “state of sciences” are enormously challenging as the reviews demonstrate great heterogeneity in terms of intervention type, content, participants, and outcome measures. The language used to describe interventions varies, and diverse disciplines were involved in the delivery of sometimes complex interventions. The limited description of intervention and content included in these approaches limits the possibility of replication and necessitates cautious comparison between studies. Although a diabetes intervention taxonomy45 is suggested and sometimes used28,46 to systematically describe the components of interventions, intervention heterogeneity remains commonplace in the current literature, making it difficult to compare results. Thus, researchers and educators should seriously consider opportunities to uniformly categorize interventions, at least for descriptive purposes.

With respect to the operational definition of outcome categories,6 clearly the most frequently used clinical improvement (postintermediate) outcome measured was A1C, and the least measured were health status improvement and QOL (long-term) outcome measures.10,16,47,48 Review articles reported limited information about instruments used in the included studies. Where available, identified QOL instruments have been included in Table 2. Overall, the most frequently cited instruments were the SF-3649 and DQOL50 to measure general and diabetes-specific QOL, respectively. Moreover, when considering key outcomes for studies, in addition to including physiological outcomes, additional patientreported outcomes should be considered. Addressing the importance of patients’ perceptions of the effects of chronic illness and its treatment has the potential to significantly improve overall DM management.51 Noted researchers32 emphasized the exclusion of outcomes such as QOL as a limitation. As telling, having looked at only A1C, other review authors28 suggest their work would have been enhanced with the inclusion of behavioral outcomes. Given the complexity of factors at many levels, which can affect processes, impact, and outcomes of care, investigators and clinicians should mindfully seek clarity in operational definitions and in better understanding the relationships of the various factors.

Interventions tailored toward high-risk populations, such as African Americans or the aged, or those with limited literacy skills have been emphasized, yet cultural relevance, literacy, and age-related concerns of interventions have been neglected in the current literature. Although several review authors31-33,46 suggest sociocultural context as an important indicator, only 3 of 12 review articles were solely dedicated to such areas. For example, Sarkisian et al29 was the only review specifically focused on older high-risk racial and ethnic groups, whereas Eakin et al33 and Glazier et al46 defined their populations of interest as low socioeconomic status (SES) or socially disadvantaged ethnic and racial adults.

The broader behavioral literature regarding tailoring of interventions must describe the lessons learned. Complete and accurate descriptions of interventions will encourage further analysis and determine interventions’ effectiveness, structure, process, and outcomes. Although attempts have been made to characterize interventions28,33,46 and employ meta-analysis,28,31,32 incomplete study descriptions and variations in content and components continue to hamper comparability. There is an urgent need to provide and document well-designed studies, systematically describing components. More important, presenting adequate information for assessments regarding study quality and broader comparability can advance the science and care of diabetes.

There are several limitations to this review of reviews. The authors were able to evaluate only what was reported, not what may in fact have been done. Together with the methodological strengths and weaknesses of the included studies, limitations of the reviews must also be considered. Finally, the search strategy and inclusion criteria for the current review may be perceived as too narrow, given that only published studies in English-language journals were selected. It is acknowledged that journal space limits what may be included in articles. Unfortunately, descriptions of intervention research fail to provide evidence of culturally tailored interventions. Also, literacy, which is known to affect care and outcomes, has not been adequately addressed. Very few studies included and/or focused on African Americans; thus, enormous gaps related to racial and ethnic groups in the literature remain.

In conclusion, this review of reviews of intervention studies shows that effects on long-term health and quality-of-life outcomes have not been adequately assessed in the current literature.30,34,35 Previous reviews26,52 provide evidence that patient-assessed health status differs from those proxy assessments made by health professionals. Although several important conceptual frameworks13,53-55 and proponents have confirmed the relevance of HRQOL as an outcome capable of affecting the effectiveness of interventions and utilization behavior, the available evidence fails to actualize HRQOL as a priority targeted outcome. Research is needed to assess long-term outcomes, such as HRQOL and its impact on specific components of interventions, particularly among diverse populations. Other researchers10,16,47,48 suggest that the initial priority should be on evaluating and refining existing HRQOL instruments. Our review confirms minimal to no testing in certain high-risk groups (Table 2). The need for disease-specific instruments, specifically validated in African Americans, becomes particularly evident in this context. Both qualitative and quantitative methods can and should be used to assess and refine existing instruments, as well as in using population-specific validated instruments to measure outcomes of clearly articulated and described interventions.

References

- 1.Bertoni AG, Krop JS, Anderson GF, Brancati FL. Diabetes-related morbidity and mortality in a national sample of U.S. elders. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:471–475. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fain JA. Understanding the importance of diabetes education outcomes: position statement and technical review. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:708. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) Standards for outcomes measurement of diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:804–816. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AADE position statement: individualization of diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:45–49. doi: 10.1177/0145721706298308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AADE position statement: cultural sensitivity and diabetes education: recommendations for diabetes educators. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:41–44. doi: 10.1177/0145721706298202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeples M, et al. Diabetes self-management education core outcomes measures. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:768–803. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AADE AADE … an organization on the move: definition of diabetes. Audio conference. 2007 May 8; [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association (ADA) [Accessed February 15, 2004];Diabetes statistics for African Americans. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics/african-americans.jsp.

- 9.Eyre H, Kahn R, Robertson RM. Preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes: a common agenda for the American Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1812–1824. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Diabetes in the United States, 2003. Rev ed CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donabedian A. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. Vol. 2. Health Administration Press; Ann Arbor, MI: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapka JG, Taplin SH, Solberg LI, Manos MM. A framework for improving quality of cancer care: the case of breast and cervical cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Ntetu A, Maltais D. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snoek FJ. Quality of life: a closer look at measuring patients’ well-being. Diabetes Spectrum. 2000;13:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuifbergen AK, Seraphine A, Roberts G. An explanatory model of health promotion and quality of life in chronic disabling conditions. Nurs Res. 2000;49:122–129. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garratt AM, Schmidt L, Fitzpatrick R. Patient-assessed health outcome measures for diabetes: a structured review. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHO-QOL) What quality of life? Vol. 17. The WHOQOL Group. World Health Forum; 1996. pp. 354–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow RE, Ruggiero L, Eakin EG, Dryfoos J, Chobanian L. Quality of life and associated characteristics in a large national sample of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:562–567. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill-Briggs F, Gary TL, Hill MN, Bone LR, Brancati FL. Health-related quality of life in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:412–419. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group (UKPDS) Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37). U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1125–1136. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services [Accessed January 6, 2002];Healthy People 2010. Available at: www.health.gov.healthypeople.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Measuring Healthy Days: Population Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polonsky WH. Understanding and assessing diabetes-specific quality of life. Diabetes Spectrum. 2000;13:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHorney CA. Health status assessment methods for adults: past accomplishments and future challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:309–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Venkat Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561–587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis SE, Speroff T, Dittus RS, Brown A, Pichert JW, Elasy TA. Diabetes patient education: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, Wintz RL, Mangione CM. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American, or Latino adults. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:467–479. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Dam HA, van der Horst F, van den Borne B, Ryckman R, Crebolder H. Provider-patient interaction in diabetes care: effects on patient self-care and outcomes. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1159–1171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:488–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18:26–35. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin SJ, Wagner EH, Eijk Van JT, Assendelft WJ. Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1821–1833. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(suppl):15–38. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steed L, Cooke D, Newman S. A systematic review of psychosocial outcomes following education, self-management and psychological interventions in diabetes mellitus. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loveman E, Royle P, Waugh N. Specialist nurses in diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. Increasing diabetes self-management education in community settings: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(suppl 4):39–66. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaefer J, Davis C. Case management and the chronic care model: a multidisciplinary role. Lippincott Case Manag. 2004;9:96–103. doi: 10.1097/00129234-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeples M, et al. Diabetes self-management education core outcomes measures. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29:768–803. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mensing C, Boucher J, Cypress M, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(suppl 1):S72–S79. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.suppl_1.s72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (DCCT) Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT). The DCCT Research Group. Diabetes Care. 1988;11:725–732. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.9.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasgow RE. Outcomes of and for diabetes education research. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25(suppl 6):74–88. doi: 10.1177/014572179902500625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown SA. Interventions to promote diabetes self-management: state of the science. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25(suppl 6):52–61. doi: 10.1177/014572179902500623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elasy TA, Ellis SE, Brown A, Pichert JW. A taxonomy for diabetes educational interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glazier RH, Bajcar J, Kennie NR, Willson K. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1675–1688. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garratt A, Schmidt L, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ. 2002;324:1417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wildes K, Greisinger A, O’Malley K. Review of quality of life measures for patients with diabetes: report of the Measurement Excellence and Training Resource Information Center, Houston Center for Quality of Care and Utilization Studies, and the Houston VA Medical Center. Available at: http://www.measurementexperts.org/learn/practice/tf-diabetes.asp.

- 49.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne C. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The DCCT Research Group Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT) Diabetes Care. 1988;11:725–732. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.9.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradley C, Speight J. Patient perceptions of diabetes and diabetes therapy: assessing quality of life. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18(suppl 3):S64–S69. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woodend AK, Nair RC, Tang AS. Definition of life quality from a patient versus health care professional prospective. Int J Rehabil Res. 1997;20:71–80. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green LW, Kreutner MW. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach with PowerWeb Bind-in Card. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill Higher Education; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips KA, Morrison KR, Andersen R, Aday LA. Understanding the context of healthcare utilization: assessing environmental and provider-related variables in the behavioral model of utilization. Health Serv Res. 1998;33:571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]