Abstract

Historically, the assisted living (AL) industry has promoted a social, non-medical model of care. Rising health acuity of residents within AL, however, has brought about the need for providing increased health care services. This article examines the key staff role related to health care provision and oversight in AL, described as the health care supervisor. It briefly describes individuals in this role (N = 90) and presents their perspectives regarding their roles and responsibilities as the health care point person within this non-medical environment. Qualitative analyses identified four themes as integral to this position: administrative functions, supervision of care staff, provision of clinical and direct care, and clinical care coordination and communication. The article concludes with recommendations for AL organizations and practice of the emerging health care supervisor role in AL.

INTRODUCTION

As an industry driven by consumer needs, assisted living (AL) provides a supportive, primarily non-medical living environment for more than one million of the U.S.’s older adults in more than 36,000 settings nationwide (ALFA, 2011), filling the gap between independent living and nursing home care (Zimmerman et al., 2001). Historically, the AL industry has generally promoted a model of care focused on resident autonomy and choice as opposed to the more structured care characteristic of the nursing home industry. But AL residents currently have an average age of 87 years as well as significant chronic health conditions and acute care needs for which AL settings must provide some medically oriented monitoring and health care services. Many older adults in AL want to avoid nursing home placement and instead prefer to age in place; i.e., experience the progression of chronic conditions that require ongoing care and monitoring within one residence. Therefore, AL increasingly provides medical as well as social care, whether by design or default. As such, AL regulations are trying to meet the growing changes within this industry, especially in terms of health care.

The increasing provision and supervision of basic health care for residents in AL represents an organizational challenge. While many AL settings do employ some licensed nursing staff (Zimmerman et al., 2005), regulations vary widely by state in terms of whether and when nurses are required; e.g., Connecticut and New Jersey require 24-hour registered nurse (RN) availability, while Iowa, Ohio, and West Virginia require that an RN be present when medications are administered or other nursing tasks are performed (Hodlewsky, 2001). In AL settings without licensed nurses, health-related monitoring, services, and communications may be overseen or coordinated by the AL administrator, owner, care manager, or a direct care worker; e.g., personal care aides. It is within this broadly ranging context that this article systematically examines the work role of the AL staff member who serves as the primary point person for health care and health-related activities in AL.

This article begins by briefly describing the characteristics of individuals in this position. Next, it presents their perspectives regarding their health care roles and responsibilities in the AL setting. For the purposes of this article, and in the absence of a common title, this project uses the title “health care supervisor” (HCS) to represent the AL staff member who fulfills this role in the AL setting. Notably, the HCS is defined as the staff member in the setting who is responsible for health care provision in the community and is most knowledgeable about residents’ health care status. The article concludes by providing recommendations for AL organizations in enhancing the work role.

Health Care in Assisted Living

As part of the long-term care system, AL is generally defined as settings or discrete portions of settings licensed by the state as a non-nursing home level of care that provide room, board, 24-hour oversight, and assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) (Zimmerman et al., 2001). Philosophically, AL seeks to minimize the need to relocate, to accommodate changing resident needs and preferences, and to maximize resident dignity, autonomy, privacy, independence, and safety (Assisted Living Quality Coalition, 1998). People typically move to AL following a health crisis/hospitalization or functional decline (e.g., cognitive impairment) that challenges their ability to live independently. Consequently, the resident profile includes notable cardiac morbidities (e.g., congestive heart failure, myocardial infarctions, angina, arrhythmias), which range from 38% to 49% (Zimmerman et al., 2003), as well as urinary incontinence for 33% of AL residents (Hawes, Phillips, & Rose, 2000). Furthermore, the typical AL resident requires assistance with two to three ADLs, such as bathing, grooming, eating, transferring, or mobility (Golant, 2004). Overall, AL residents nationwide have many similarities with nursing home residents in terms of acuity, comorbidity, impairment in ADLs, and cognitive impairment (Manard & Cameron, 1997). As a result of rising acuity, AL settings are often faced with an array of health-related responsibilities (Polzer, 2011).

On a broader level, AL settings and HCSs have emerged and are influenced by a number of larger social and political dynamics. As noted above, consumer demand for a homelike, supportive, non-nursing home environment has influenced the rapid growth of the industry. Consumers also prefer aging in place and avoiding transitions to settings with higher levels of care that directly impact the type of supportive services and personnel an AL may need to provide. In terms of financing, the AL industry has been largely private-pay, with only modest levels of government payment for AL services; e.g., New Hampshire waiver programs. Regulation in AL remains at the state level and is highly heterogeneous among states, particularly in terms of health care (Mollica, 2008). A federal request to examine AL issues resulted in the development of an Assisted Living Work Group Report (2003), which achieved broad consensus yet some differing opinions in areas including resident wellness and health care needs. Finally, issues relating to the quality of health care in AL have been the focus of numerous investigative news reports. Serious allegations include resident neglect, lack of health care expertise, and inadequate standards of care (Washington Post, 2004; Consumer Reports, 2005; Miami Herald, 2011). Collectively, these social and political dynamics suggest the compelling need to systematically examine, describe, and begin to understand the role of health care supervision within the AL industry.

METHODS

Sample and Procedure

The study definition of AL included any setting that was not licensed as a nursing home and was licensed by the state to provide room, oversight, at least one meal per day, and support with ADLs.

Two strategies were used to obtain the sample. The first was a stratified random sample of AL settings in Florida, New Mexico, and Wisconsin—states that were selected due to differences in their AL regulations and industry. Settings that primarily served persons with mental retardation or developmental disabilities were excluded, as were settings with fewer than 16 beds that housed fewer than four residents 65 and older and settings with 16 or more beds that housed fewer than 10 residents 65 and older. Eligible settings were then stratified into three types according to the well-established typology developed by the Collaborative Studies of Long-Term Care (CS-LTC; Zimmerman et al., 2001): “smaller” – those with fewer than 16 beds; “new-model” – those with 16 or more beds, tending to have nursing support or more impaired residents; and “traditional” those with 16 or more beds that do not meet the new-model definition. Within each stratum, eligible AL settings were recruited in random order until five in each stratum had been recruited in each state (N = 45).

In a second sampling strategy, AL settings were identified by physicians/medical care providers who completed surveys at two national geriatric professional association meetings. As part of the survey, respondents were instructed to record the name and contact information associated with the AL setting on which survey results were based. Using this strategy, an additional 45 AL settings were recruited for a total sample size of 90 settings.

Recruitment

Each AL administrator was sent a recruitment package either by mail or fax that included informational study materials (e.g., introductory letter and study brochure), as well as a letter of support from the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA). Next, administrators were telephoned approximately one week after the letter was sent to explain what was involved in participation, to obtain agreement to participate, gather descriptive information on the setting, and to identify the HCS; i.e., the staff member who is responsible for health care provision. Functionally, the HCS is the staff member who is most knowledgeable about residents’ health care situation and who most frequently communicates with external health care providers, particularly physicians. This person may be the AL owner/manager, a health care manager, a nurse, or a direct care provider. Based on the design, one person was identified in this role, relying on the guidance of the AL administrator.

The HCS was then contacted to participate in a telephone interview regarding his/her role and experience with primary medical care providers in AL. All HCSs received a consent information sheet detailing their rights as study participants. HCSs provided verbal consent to participate before data were collected. Interviewees were notified prior to the interview that the telephone call would be tape-recorded for data collection purposes. The interviews were then transcribed verbatim.

The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) approved participant enrollment and data collection procedures. Recruitment and data collection were conducted over a 19-month period (September 2008–July 2010).

Measures

AL administrators provided information by telephone regarding setting characteristics; e.g., profit status, number of licensed beds, years in operation, presence of medical director, and resident demographics. The HCSs participated in semi-structured, recorded telephone interviews addressing their demographic and professional characteristics. A combination of closed- and open-ended questions explored the experience of health care delivery and staffing in AL, with a focus on the HCSs’ roles and responsibilities. The primary open-ended question analyzed in this article was, “In general, how would you describe your roles/responsibilities in terms of health care?”

ANALYSIS

Quantitative data analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows 18.0. Qualitative analysis of the open-ended responses regarding their health care roles and responsibilities was conducted using collaborative coding (Eckert et al., 2009) by a multidisciplinary team of six co-investigators comprised of sociologists, anthropologists, and gerontologists. The data and codes were initially managed with Atlas.ti software. Next, each investigator independently reviewed, coded, and analyzed the data. Finally, the full team met to discuss and reconcile the differences in assigned codes. This process of developing codes enabled the team to analyze the data further and, through a consensus model, identify salient thematic categories regarding the roles and responsibilities of the HCS.

FINDINGS

Settings and Resident Demographics

In total, 90 AL settings were enrolled in the study: 16 (18%) with fewer than 16 beds (“smaller”), 26 (29%) “traditional” AL settings, and 48 (53%) “new model” settings. The AL settings represented in this study averaged 14 years in operation and reported an average of 57 licensed beds. About three-quarters were for-profit (74%), more than one-third had a medical director on staff (38%), and 78% reported not being contractually affiliated with a physician practice. In terms of resident composition, settings reported an average of 42% of residents over age 85, 91% white, 5% Hispanic, 24% male, 3% with developmental disabilities, less than 1% bedfast, and 44% of residents with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1.

Table of Assisted Living Community Characteristics.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or Number (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Community type | ||

| Smaller (< 16 beds) | 16 | (18%) |

| Traditional | 26 | (29%) |

| New model | 48 | (53%) |

| Ownership status | ||

| For-profit | 67 | (74%) |

| Non-profit | 22 | (24%) |

| Number of licensed beds, mean (SD)a | 56.5 | (46.5) |

| Years in operation, mean (SD) | 13.7 | (11.8) |

| Medical director on staff | 34 | (38%) |

| No contractual affiliation with physician practice | 70 | (78%) |

| Resident demographics, mean (SD) | ||

| > 85 years old | 42.1 | (29.5) |

| Male | 24.3 | (16.4) |

| White/Caucasian | 90.6 | (18.9) |

| Hispanic | 5.1 | (16.2) |

| Developmentally disabled | 2.6 | (9.3) |

| Bedfast | .63 | (1.6) |

| Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia | 44.3 | (29.5) |

Notes: N ranges from 87–90 due to missing data.

Bed sizes range from five to 225, with a median of 47.

Description of Health Care Supervisors: Demographics and Training

The typical respondent in our sample was a non-Hispanic (90%), white (80%), female (91%) averaging 48 years of age. Most HCSs had a community college degree (46%) as their highest level of education, while 13% had only high school credentials (Exhibit 2). More than 40% completed four or more years of college.

Exhibit 2.

Table of Health Care Supervisor Demographics.

| Variable | Mean (SD) or Number (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.4 | (10.7) |

| Female | 82 | (91%) |

| Race | ||

| African American | 3 | (3%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3 | (3%) |

| Asian | 4 | (4%) |

| White | 71 | (80%) |

| Other (e.g., South American, Latino/a, biracial) | 8 | (9%) |

| Hispanic | 9 | (10%) |

| Education | ||

| High school graduate/GED | 12 | (13%) |

| Some college or community college graduate | 41 | (46%) |

| 4-year college graduate | 25 | (28%) |

| Post-graduate (beyond 4-year college) | 12 | (13%) |

| Traininga | ||

| RN or NP | 32 | (36%) |

| LPN | 25 | (28%) |

| Other medical (e.g., CNA, medication technician) | 12 | (13%) |

| Other, non-medical (e.g., MBA, marketing) | 21 | (23%) |

| Tenure in facility at time of interview, mean (SD) | 4.9 | (5.2) |

| Worked in nursing home | 58 | (64%) |

Notes: N ranges from 89–90 due to missing data.

Multiple answers possible; therefore, total does not equal 100%.

Two-thirds of the HCSs in the study were certified with medical credentialing: RNs/nurse practitioners (NPs) (36%) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) (28%). Thirteen percent were certified nursing assistants who were trained to administer medications, and close to one-fourth of those serving in the role of HCS (23%) had less medical training. Participants in our sample, on average, had served as the HCS in their current work setting for close to five years, and 64% had previous work experience in the nursing home environment (Exhibit 2).

Although many participants in our sample were credentialed and trained regarding medical services, it should be noted that more than 10% were not educated beyond the high school level, and almost 25% had no health care credential or health care training but are broadly positioned with responsibility for health-related decisions and issues. Within this context, this article turns to the HCSs’ own descriptions of their roles and responsibilities related to their health care position in AL settings.

The Multidimensional Role of the HCS

When asked, “In general, how would you describe your roles/responsibilities in terms of health care?” the HCSs in this study spoke broadly and at length about their position. Their most common response: seeing themselves as doing “everything” in the AL setting related to residents’ care needs (health or otherwise) and at times alluding to being the beginning and end of all matters related to resident care in AL. In general, there seemed to be very few boundaries regarding what HCSs considered to be part of their job (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3.

Multidimensional Responsibilities of Health Care Supervisors.

| “Well, I do everything…sometimes you’re administrator, sometimes you’re payroll. I mean, I do payroll, scheduling, staffing, everything actually…I am very involved…I go in the dining room and help assist with meals. I monitor my residents. When they are given showers or something, I would go in and assist at times, so I can monitor their skin…” |

| “I am a caregiver as well. I’m the cook, I do the shopping, I run the organization, I run everything. I do the firing, hiring, all the meetings with the state. I do have to handle all the training…” |

| “I usually take care of the whole facility. I mean cooking their lunch, or cooking their breakfast, and making sure that all the cleaning’s being done and housekeeping done…I do showering, and we give out, we assist with the medications… I do everything also.” |

| “Completely responsible for these residents, make sure that they’re…all their care is given to them… I do all that kind of stuff…I do…direct care…” |

| “Well, I would say my role was, as overseeing what the other staff is doing, coordinating the care, and, you know, making out the schedules for the employees, taking care of all the paperwork…” |

| “If a resident’s not feeling well, or something’s wrong, I have direct contact with their physician to let the physician know what’s going on and take any new orders, which could include medication or scheduling appointments for follow-up.” |

| “I coordinate with the doctors…If there is an emergency then the doctor…is called for authorization. If there is a real emergency like somebody falls…then I send them out directly to the emergency unit. And after that I inform the doctor…And, like, make appointments for doctors’ visits, coordinate their transportation…” |

| “Well, I oversee all of the coordination of care…Making sure that if any problems are noted by staff or myself that doctors are notified of medication changes or anything like that…” |

| “…because we know the resident so well, if, you know, we observe them on a daily basis, if I see any changes in them whatsoever…I will report it to their doctors immediately…” |

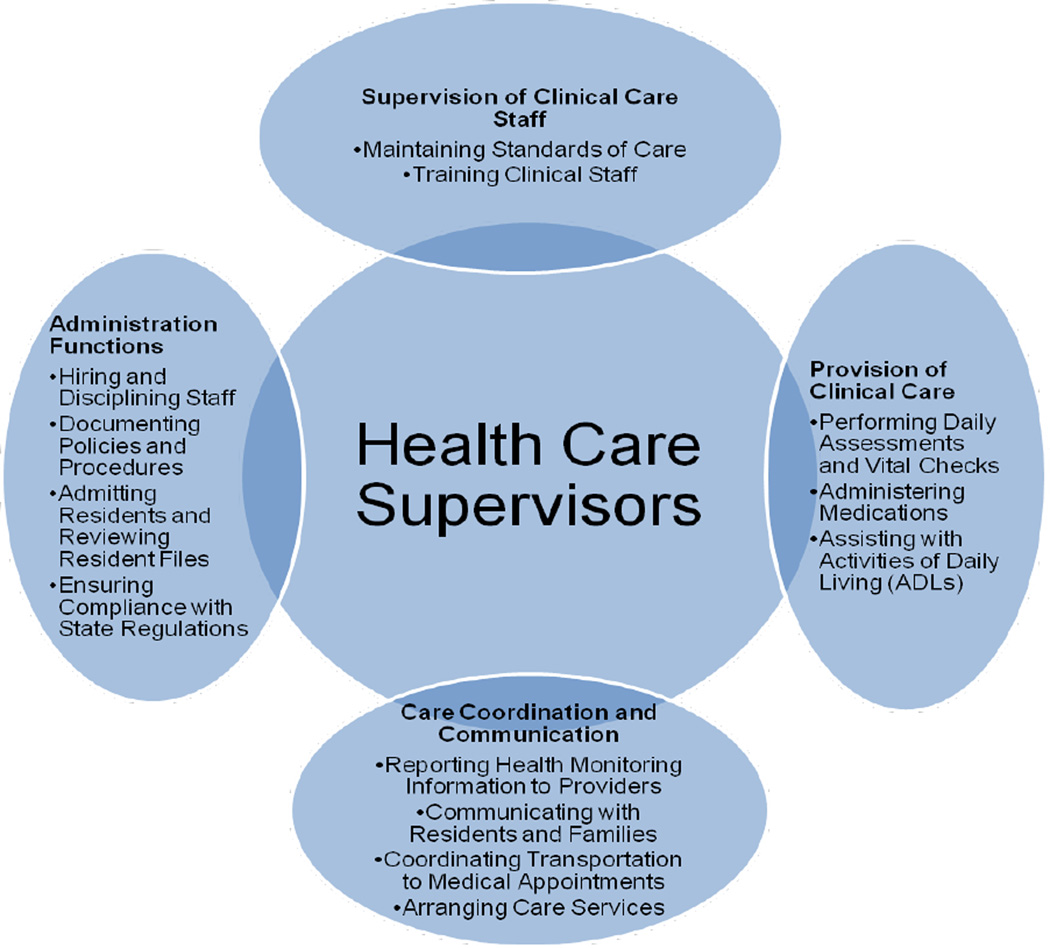

Drilling down into this strong sense of the HCSs doing “everything,” four major themes were identified representing the HCSs’ self-described work role in AL: 1) administrative functions; 2) supervision of care staff; 3) provision of clinical and direct care; and 4) clinical care coordination and communication (Exhibit 4).1 HCSs conceptualized their role in terms of an administrative function, with responsibility for staff scheduling, hiring, firing, record keeping/paperwork, and upkeep of state compliance/licensure. Supervision of care staff involved HCSs providing oversight of staff and developing ongoing training; e.g., universal precautions. HCSs also reported routinely providing clinical and direct care services ranging from doing dressing changes and assisting with ADLs to housekeeping tasks; e.g., cleaning and cooking. The final HCS theme focused on clinical care coordination and communication activities. HCSs responded that they reported health monitoring information to primary medical care providers (e.g., physicians), coordinated transportation to medical appointments, and arranged other health care services. Moreover, HCSs often embraced the coordination role, seeing themselves as a liaison between health care providers and AL residents, sometimes identifying themselves as resident advocates, as represented here: “I’ll fight for their [residents’] rights. I don’t care if it’s a Sunday and a lab result came in; it’s their [physician’s] job. Our job is to call them and notify them of what’s going on. Their job is to call me back, and I will keep bothering them until they do, to get what my resident needs…” And “Well, my role, from the nursing standpoint is, you know, I do daily assessments of my patients, and if I find problems, I communicate with their physician. I’m a patient advocate. As far as getting their needs met [by the physician], when I notice problems…If I find out there’s a problem, and I find there’s been any kind of change or decline, or, you know, acute problems, infections, things like that, I will call the physician.”

Exhibit 4. Health Care Supervisor Conceptual Framework.

Beyond the aforementioned four themes, a subtheme across HCSs was the sense that the primary medical care providers generally lacked understanding of the scope and limitations of AL health care services (Exhibit 5). This lack of provider understanding was repeatedly reported and, at times, perhaps seen as a challenge to efficiently carrying out their roles and responsibilities in coordinating care services.

DISCUSSION

The study provides an initial look into the role of the HCS in AL, with findings from interviews with 90 HCSs across a range of AL settings providing a clearer understanding of their work role. The belief that they do “everything” was pervasive throughout the transcripts, as evidenced by consistent reports of administrative duties, supervisory responsibilities, care provision, and care coordination. This omnibus role, however, is limited in its scope by external control factors such as AL licensure scope of practice limits, the limited medical training of some HCSs, and that HCSs are not physicians and so may be asked to carry out orders made by primary care medical providers who are typically outside of the setting and are not knowledgeable of the scope of practice in AL; i.e., 78% of settings in this sample were not contractually affiliated with physician practice as presented in Exhibit 1. For HCSs working in AL, these dynamics have the potential to create stressful role overload as seen in this representative quote: “…all the nursing role…I do all of that myself…the charting, the faxing lab works, everything to the doctor, taking telephone orders, ordering medications, doing the medication logs, and everything…that’s why I’m asking for help!”

Results of this study suggest that AL organizations examine the scope of the HCS position in relation to AL resident’s needs and the potential for role overload, stress, and burnout among HCSs. Findings show that HCSs feel responsible for multiple and divergent administrative, supervisory, clinical, and communication tasks, and so it may be necessary for AL organizations to more clearly define and limit the scope of the HCS role, especially in cases when the demands exceed the educational or professional training of the HCS. Furthermore, AL organizations could use the HCS themes identified here and prioritize them according to their importance within the setting; e.g., a “traditional” setting with higher functioning residents (i.e., less physically and cognitively impaired) may find it more important to focus on administrative functions and less important to tend to actual provision of care. Articulating this structure might result in a HCS position, for example, that explicitly calls for someone to perform duties related to documenting health care policies and procedures and ensuring compliance with state oversight agencies. Providing limits of the work role may ensure that HCSs are able to efficiently carry out duties and are not overwhelmed in doing so.

CONCLUSION

This research explores the duties and responsibilities associated with the role of the HCS from the workers’ perspectives, a role that is increasingly important as resident acuity in AL rises. While this study was limited to a survey of only 90 HCSs, it indicates the centrality of these responsibilities to resident health and welfare. Moreover, it points to confusion about the capabilities and limitations in serving the complex needs of the AL population and the burden these challenges place on a single individual. Given that there are more than 36,000 AL settings in the U.S., data from a larger sample are needed to better understand the HCS role and related issues.

Future Directions

Future research should delve deeper into an examination of work satisfaction and work role stressors of the HCS (e.g., conflict in working relationships), which can make executing the myriad of tasks in this position difficult to accomplish. Of note, this work reveals that HCSs are particularly frustrated by the lack of knowledge that residents’ primary medical care providers/physicians have regarding the AL regulatory structure; e.g., because AL is state regulated, staffing guidelines differ and are not always as clearly defined as in other long-term care institutional settings such as nursing homes. Therefore, there is greater flexibility and role ambiguity in terms of health care staffing in AL, as evidenced by the findings. In order to alleviate some of the frustration regarding knowledge of regulations, AL communities themselves might create material oriented to these providers regarding the organizational composition of AL and its inherent limitations regarding health care. Guidelines for developing medical provider education materials have been documented in the literature (Schumacher, 2005), and it is likely that providing information about AL regulations to medical providers may lessen the disconnect between provider expectation and HCS ability.

Exhibit 5.

Lack of Medical Care Provider Knowledge of Assisted Living Regulations, as Reported by Health Care Supervisors.

| “…Well, I think they don’t realize the limitations of the standard license, so they think that we are able to provide dressing changes, help with oxygen and so forth, even feeding in some instances, which is not allowed, you know.” |

| “…A lot of times I think they expect for us to provide the same thing a nursing home or a skilled nursing facility would provide, and we can’t do that. There’s a lot of things that…asked if we provided here, that I as a nurse, anywhere else I’ve worked have been able to do, and nursing things here that I’m not allowed to do, just because of the licenses that the facility holds.” |

| “I think oftentimes doctors are confused that we are a non-medical facility and think that we can provide more care than we actually can. We’re non-medical, we don’t provide nursing. I think they become a little upset when we can’t do wound care but are always willing to provide an order for a nurse to come out and you know, so…they think we’re more medical than we actually are. If they maybe came to see what we’re about…I don’t think they understand we don’t have nurses and you know and PAs [physician’s assistants] on duty at all times. They think we can just take an order verbally, and that’s one thing we can’t do everything has to be in writing…Well, I think they just think that as long as they called us and they told us it’s okay is what we were requesting that should be enough, and I don’t think they understand that without written orders we can’t do a thing…you know not being out of the ordinary I just think that’s the most common is that when they call us back if we say we’ve called and we’ve said you know so-and-so can’t take a certain medication, ‘Can we change this or can we discontinue this?’ They’ll call back and say, ‘Yeah go ahead and discontinue it.’ Well, then we have to say, ‘Well I really need it in writing,’ and they’re like, ‘Well, why do you need it in writing, I’m just telling you that you know, you can discontinue it.’ And we’re like, ‘Well, it’s regulations state that we can’t do it.’ I don’t think they understand that about assisted living in general.” |

| “…I just think the doctors, they just don’t know. Because they don’t come into our facilities…[a physician] will say, ‘I need you to do an in-and-out cath on so-and-so, and I need a CBC and this, this, this, this.’ And I’m like, ‘Um, we don’t do that here. This person’s private-pay; they’re not set up with home health, but if you give me a referral fax, I will get them set up and they can come in and do it.’ And they’re like, ‘Well, why can’t you do it?’ You know, the same people, no matter how many times you tell them, it’s the same doctors who still come back with the same. So you are, you’re continuously pretty much, you’re the one to educate them…And so my issue is, with several of the doctors…you are the one that made the recommendation for your patient to be placed in this facility, and you don’t even know what we do…I’m saying, you know, you don’t even know what we offer. And I do have an issue with this. You’re putting your patient in here, and it could be a patient that they had for 30 years. And you are recommending, ‘Well, hey, I think you should go to [AL facility],’ and then when they get here they actually don’t even know where they sent them…You know, so, I do have a big thing with that. A big thing.” |

Footnotes

Investigators qualitatively evaluated whether there was role variation between the two samples (randomized and convenience) and the three strata (small, traditional and new-model) and found that the dominant theme of multiple roles was consistent across samples, suggesting stability in the findings.

Contributor Information

Brandy Harris-Wallace, Assistant Research Scientist, Center for Aging Studies, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Public Policy 252, Baltimore, MD 21250, bhwalla@umbc.edu.

John G. Schumacher, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Public Policy Building 252, Baltimore, MD 21250, jschuma@umbc.edu.

Rosa Perez, Center for Aging Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Public Policy 252, Baltimore, MD 21250, rperez@umbc.edu.

J. Kevin Eckert, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Public Policy Building 252, Baltimore, MD 21250, eckert@umbc.edu.

Patrick J. Doyle, Doctoral Program in Gerontology, Graduate Research Assistant, Center for Aging Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Public Policy Building, 2nd Floor, Baltimore, MD 21250, pdoyle1@umbc.edu.

Anna Song Beeber, Research Fellow, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 725 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Chapel Hill, NC 27599, asbeeber@email.unc.edu.

Sheryl Zimmerman, Program on Aging, Disability, and Long-Term Care, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 725 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Campus Box 7590, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, Sheryl_Zimmerman@unc.edu.

REFERENCES

- Assisted Living Federation of America. [ALFA] What is Assisted Living? 2011 Retrieved from http://www.alfa.org/alfa/What_is_Assisted_Living1.asp?SnID=1433259030.

- Assisted Living Quality Coalition. Assisted Living Quality Initiative. Building a structure that promotes quality. Washington, D.C.: Public Policy Institute, American Association of Retired Persons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Reports. CR Investigates: Assisted Living, how much assistance can you really count on? Washington, D.C.: Consumers Union; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth E. Inside Assisted Living: The search for a home. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. Do impaired older persons with health care needs occupy U.S. Assisted Living facilities? An analysis of six national studies. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. 2004;59(2):S68–S79. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes C, Phillips CD, Rose M. High service or high privacy Assisted Living facilities, their residents and staff. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hodlewsky RT. Staffing problems and strategies in assisted living. In: Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, editors. Assisted Living: Needs, practices and policies in residential care for the elderly. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Manard BB, Cameron R. A national study of Assisted Living for the frail elderly: Report on in-depth interviews with developers. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, the Administration on Aging and the National Institute on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Miami Herald. Neglected to Death -- Part 1: Once pride of Florida; now scenes of neglect. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.miamiherald.com/2011/04/30/2194842/once-pride-of-florida-now scenes.html#ixzz1NNoxyv00).

- Mollica R. Trends in state regulation of Assisted Living. Generations. 2008;32(3):67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Polzer K. Assisted Living state regulatory review. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Assisted Living; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JG. Assisted living communities and medical care providers: Establishing proactive relationships. Seniors Housing & Care Journal. 2005;13:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- The Dangers of Virginia Assisted Living: A Washington Post Investigation. Washington Post. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/content/nation/investigative/assistedliving.html.

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, editors. Assisted Living: Needs, practices and policies in residential care for the elderly. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Gruber-Baldini AL, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, Hebel JR, Morgan LA, et al. Assisted living and nursing homes: Apples and oranges? The Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):107–117. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, Gruber-Baldini AL, Morgan LA, Hebel JR, et al. How good is assisted living? Findings and implications from an outcomes study. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. 2005;60B:195–204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.s195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]