Abstract

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) is a multisystem genetic disorder with distinct facies, growth failure, intellectual disability, distal limb anomalies, gastrointestinal and neurological disease. Mutations in NIPBL, encoding a cohesin regulatory protein, account for >80% of cases with typical facies. Mutations in the core cohesin complex proteins, encoded by the SMC1A, SMC3 and RAD21 genes, together account for ∼5% of subjects, often with atypical CdLS features. Recently, we identified mutations in the X-linked gene HDAC8 as the cause of a small number of CdLS cases. Here, we report a cohort of 38 individuals with an emerging spectrum of features caused by HDAC8 mutations. For several individuals, the diagnosis of CdLS was not considered prior to genomic testing. Most mutations identified are missense and de novo. Many cases are heterozygous females, each with marked skewing of X-inactivation in peripheral blood DNA. We also identified eight hemizygous males who are more severely affected. The craniofacial appearance caused by HDAC8 mutations overlaps that of typical CdLS but often displays delayed anterior fontanelle closure, ocular hypertelorism, hooding of the eyelids, a broader nose and dental anomalies, which may be useful discriminating features. HDAC8 encodes the lysine deacetylase for the cohesin subunit SMC3 and analysis of the functional consequences of the missense mutations indicates that all cause a loss of enzymatic function. These data demonstrate that loss-of-function mutations in HDAC8 cause a range of overlapping human developmental phenotypes, including a phenotypically distinct subgroup of CdLS.

INTRODUCTION

Cornelia de Lange syndrome and cohesin

Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS; or Brachmann-de Lange syndrome, OMIM 122740, 300590, 610759 and 614701) is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with congenital malformations that include characteristic facial features, growth retardation, intellectual disability and limb anomalies. Typical CdLS is caused by de novo, heterozygous mutations in NIPBL (1–7), and recent data have demonstrated that as many as 20% of individuals may have mosaic mutations that are not readily detectable in blood (8). NIPBL encodes the human ortholog of the Drosophila Nipped-B (9) and yeast Scc2 proteins, key components of sister chromatid cohesion (10). NIPBL is required for the chromosomal loading of the cohesin complex (11,12), which comprises four highly conserved subunits: SMC1, SMC3, RAD21 (hSCC1) and STAG (SCC3/SA) (13). Approximately 5% of patients with CdLS, usually those with milder congenital anomalies or atypical facial features, have mutations in the human SMC1A gene (14,15). One patient has been reported with a mutation in the SMC3 gene (16) and several have been noted with mutations in RAD21 (17). However, 10–20% of patients with typical CdLS have no identified etiology. In addition, a high number of individuals with atypical CdLS or an overlapping phenotype have no identified cause.

Acetylation of SMC3 and the role of HDAC8

The acetylation of SMC3 at key lysine residues is required to establish the cohesiveness of chromatin-loaded cohesin during S-phase (18–20). In addition, SMC3 is rapidly deacetylated during mitosis (19–21) and was noted in yeast to be regulated by the class I deacetylase Hos1 (22–24). We recently identified HDAC8 as the vertebrate SMC3 deacetylase and demonstrated its role in recycling cohesin from one cell cycle to the next (25). Furthermore, we identified HDAC8 mutations in six individuals with typical CdLS or an overlapping phenotype.

To investigate and fully characterize the range of clinical features in patients with HDAC8 mutations, we screened an internationally assembled cohort of 586 patients with typical CdLS and overlapping clinical presentations who had no known molecular etiology. Here we report on a range of mutations, including chromosomal aberrations, nonsense and missense mutations that disrupt HDAC8 and clarify the clinical spectrum of features in individuals with these mutations. This study demonstrates the range of phenotypes caused by HDAC8 mutations in an emerging era of genomic/exomic sequencing, since seven subjects herein were identified by genomic studies (array and exome sequencing) independent of a CdLS diagnosis. This work serves to emphasize the range of features seen in individuals with HDAC8 mutations and underscores their distinctness from typical CdLS. Furthermore, it portends the likelihood that additional subjects will be identified by NGS approaches.

RESULTS

We recently identified HDAC8 as the vertebrate deacetylase responsible for deacetylating cohesin to facilitate its recycling (25) and identified mutations in a small number of subjects from a cohort of children with CdLS. Also recently, a family with an X-linked pattern of obesity and mental retardation in males was noted to have an intronic HDAC8 mutation that segregates with the phenotype (26). To further clarify the clinical consequences of HDAC8 mutations in human developmental disorders, we assembled a large international cohort of individuals with CdLS and overlapping phenotypes and screened for mutations.

Identification of HDAC8 mutations in a large cohort of patients

We assessed 586 individuals with CdLS and overlapping phenotypes for whom screening for mutations in NIPBL, SMC1A and, in most cases, SMC3 (see Materials and Methods) was negative. Among this cohort, we identified 25 probands, three affected family members and three unaffected mothers with mutations in HDAC8, revealing a cause in ∼4% of probands. In addition, two children were ascertained by discovery of de novo HDAC8 microdeletions and five as a result of identifying a de novo HDAC8 mutation using clinical exome sequencing, all these latter cases prior to considering the diagnosis of CdLS. In total, including the six previously reported individuals (25), this includes six different chromosomal microdeletions or microduplications, three nonsense mutations, one splice site and 16 different missense mutations (Fig. 1). Of the mutations, 23 occurred de novo in the affected child, six were maternally inherited (in four families) and in seven the inheritance could not be fully confirmed.

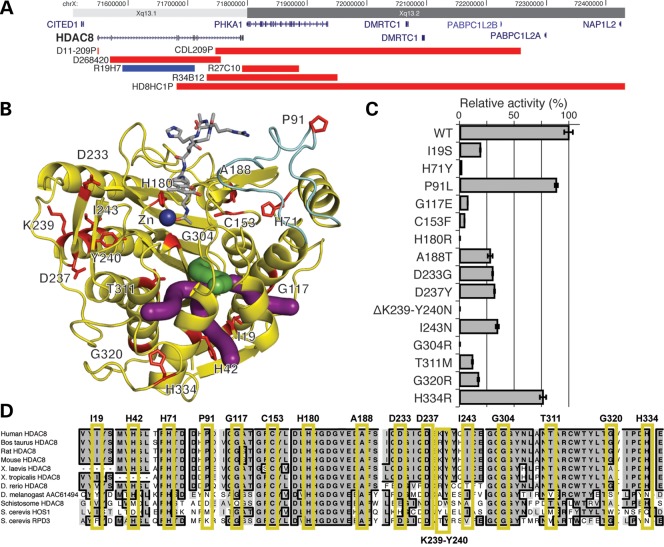

Figure 1.

Mutations in HDAC8. (A) Copy number abnormalities that disrupt the HDAC8 locus. Localization of deletions (red) and duplications (blue) on Xq13 are indicated by chromosome band and position (hg19). Gene locations are indicated in blue with gene names. HDAC8 is indicated in bold. (B) Localization of HDAC8 missense mutations on the crystal structure (PDB accession code 2V5W (27)). Mutated residues are in red and labeled. The acetylated substrate is in gray and the active site zinc ion (Zn) is in dark blue. The light blue portion indicates the L2 substrate-binding loop. Green and purple tubes indicate the catalytically important main and branch exit channels, respectively, for the acetate hydrolysis product (28,29). (C) HDAC8 mutations disrupt deacetylase activity. Bar graphs demonstrate the effect of HDAC8 mutations on deacetylase relative activity relative to the wild-type enzyme activity (specific activities are noted in Supplementary Material, Table S1). All assays were performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Enzymatic activity for all mutations is significantly less than wild type (P <0.05) using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Single letter amino acids are used for mutation notation to correlate with residues in (B and C). (D) Conservation of mutations in HDAC8. Alignment of HDAC8 and related deacetylases from 10 species, as indicated on the left. Residues identical to the human residue in a majority of species at each position are in bold, in dark gray and a black border. Those that are similar are shaded in lighter gray, without a border. Each mutated human residue is indicated at the top, with a yellow box surrounding the aligned residues. Note the conservation through yeast for all residues in which a missense mutation causes a complete loss of function.

HDAC8 mutations in CdLS cause loss of enzyme activity

To obtain independent data regarding the effect and severity of these mutations on protein function, we mapped mutations onto the previously reported crystal structure of HDAC8 (27,30) (Fig. 1B) and expressed the wild type and each of the mutated forms of HDAC8 in Escherichia coli. We purified each and assayed deacetylase activity using a commercially available HDAC8 assay (31) (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Material, Table S1).

Wild-type HDAC8 requires a single zinc ion for the hydrolysis of N6-acetyllysine side chains in acetylated protein substrates such as SMC3 (blue sphere in Fig. 1B). The side chains of D178, H180 and D267 coordinate to the zinc ion and play a critical role in stabilizing the active site structure and modulating the chemistry of the zinc ion for catalysis (32). X-ray crystal structures of inactive HDAC8 mutants complexed with peptide substrates reveal extended regions of the protein surface capable of interacting with protein substrates, including a portion of the L2 loop (light blue in Fig. 1B) that exhibits moderate flexibility in the binding of substrates and inhibitors (27,30,33,34). A catalytically important internal channel leading to possible exit channels for the acetate hydrolysis product has been identified in modeling and mutagenesis studies (green and purple tubes in Fig. 1B) (28,29). This channel may facilitate catalysis when HDAC8 is bound to large protein substrates by providing a "back door" exit for the small product without first requiring dissociation of the HDAC8-substrate complex. Inspection of mutation sites mapped onto the HDCA8 structure reveals that most appear capable of compromising molecular features required for optimal catalytic function.

Based on structural location and enzymatic activity, mutations are classified into four groups. The first group of mutations (H180R, G304R, H71Y and ΔK239-Y240N) completely inactivate the enzyme. The H180R mutation destroys the binding site of the catalytically obligatory zinc ion. The G304R mutation introduces a large positively charged residue near the active site that might destabilize the protein structure and/or block substrate binding. The H71Y substitution disrupts hydrogen bonds with the backbone NH group of N156 and the backbone carbonyl groups of K145 and K146, which may destabilize the L2 loop and adjacent residues that accommodate substrate binding. Finally, the positively charged amino group of K239 makes an electrostatic interaction with D355 and donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyl group of N357. While the side chain of adjacent residue Y240 does not make any hydrogen bond interactions with protein residues, it is close to the active site. The deletion of K239 and the simultaneous Y240N mutation suggests they perturb the protein scaffold in the vicinity of the active site to abolish catalytic activity.

The second mutation group, comprised of G117E and C153F, is characterized by residual enzyme activity less than 10% of that observed for the wild-type enzyme. The larger, negatively charged glutamate side chain of G117E would be oriented toward solvent. However, it could sterically perturb the conformation of the adjacent K60-A62 polypeptide segment, to destabilize the nearby L2 loop. C153 is located only ∼10 Å away from the catalytically obligatory zinc ion, and it is also close to H142 and H143, residues that are known to be involved in catalysis (30,32). The substitution by a larger hydrophobic phenylalanine is likely to dramatically remodel the active site and thus impair catalysis.

A third group of mutations (T311M, I19S, G320R, A188T, D233G, D237Y and I243N) exhibit ∼10–50% residual activity compared with the wild-type enzyme. The T311M mutation may perturb the putative internal channel for product acetate dissociation, and the I19S may perturb one of the possible acetate exit channels that branch away from the internal channel. Additionally, the T311M and G320R mutations may compromise the active site structure, since the helix containing these residues (helix H2) buttresses the β-sheet comprising one wall of the active site. The T311 hydroxyl group also donates a hydrogen bond to the backbone carbonyl group of N307, and disruption of this hydrogen bond by the T311M mutation would destabilize the protein. The guanidinium side chain in the G320R mutation would occupy a cleft on the surface of the protein, but it is difficult to explain how this particular substitution might influence the active site structure. A188 is in a hydrophobic environment, surrounded by F70, V159, L163, V185 and F189; mutation to a larger, partially hydrophilic residue might subtly affect packing interactions. D233 is located on the protein surface, but its carboxylate group accepts a salt-linked hydrogen bond from the side chain of K202. The deletion of the carboxylate group in the D233G mutant disrupts this interaction; being moderately close to the active site, this mutation might cause some subtle structural changes that compromise catalysis. The carboxylate side chain of D237 accepts hydrogen bonds from the side chain hydroxyl group and the backbone NH group of T280, and D237 is moderately close to the active site. Mutation of D237 to a less polar residue in the D237Y mutant probably causes a structural rearrangement that propagates through to the active site. Finally, while I243 is a partially conserved residue among the HDAC isozymes, analysis of the HDAC8 structure does not suggest any particular reason for the loss of activity resulting from this mutation.

A fourth group of mutations (P91L and H334R) exhibit relatively minor but significant losses of catalytic activity (residual activities >50% compared with the wild-type enzyme). H334 is located on the protein surface far from the active site, and P91L is in the portion of the L2 loop that is most distant from the active site.

The varying loss of activity of these mutations also correlates with the amino acid conservation at each site (Fig. 1D). Each of the substitution mutations that result in complete ablation of activity (H71Y, H180R and G304R) alters a residue that is identical from humans through yeast. Mutations with minor or intermediate losses of activity largely reside in residues that are less conserved in non-vertebrates, although nearly all mutations occur in residues that are nearly identical in vertebrates, consistent with the overall high conservation of sequence in vertebrate HDAC8 homologs.

HDAC8 mutations are associated with severely skewed X-inactivation

To assess the HDAC8 mutations effect on RNA, we evaluated expression in cell lines available for several of the probands. We noted that for a male subject (case ID CDL426P), with a hemizygous missense mutation, the mutant transcript was detectable, as expected for this X-linked gene. However, for available lymphoblastoid cell lines from females (CDL016P, CDL209P, CDL248P, CDL317P and CDL603P) that harbored heterozygous missense mutations (Table 1), we were only able to detect the wild-type allele, even in the presence of the nonsense-mediated decay inhibitor cycloheximide. Since blood cell lines freely mix and would be expected to demonstrate biallelic expression, this inability to detect the mutant allele suggested selection for expression of the normal allele in these cell lines or in peripheral blood prior to their establishment. We then analyzed the allelic expression in a fibroblast cell line from the female probands CDL016P and CDL248P, the only two subjects for whom both lymphoblastoid and fibroblast cell lines were available. We reasoned that the line derived from a small skin biopsy had a better possibility of being clonally derived and would be less subject to selection. Consistent with this possibility, these cells expressed only the mutant allele, also supporting the likelihood of selection within the peripheral blood (25) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Skewed X-inactivation with HDAC8 mutations

| Patient | DNA source | Gender | Allele 1:Allele 2 | cDNA allele expressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0007 | Blood | Female | 97:3 | N/A |

| C0084 | Blood | Female | 98:2 | N/A |

| C0146 | Blood (3 years 7 months) | Female | 16:84 | N/A |

| CDL016P | Blood | Female | 100:0 | 100% wt |

| CDL016P | Fibroblast | Female | 0:100 | 100% mut |

| CDL179P | Blood | Male | 100 | N/A |

| CDL209P | Blood | Female | 100:0 | 100% wt |

| CDL231P | Blood | Female | 0:100 | N/A |

| CDL233P | Blood | Male | 100 | N/A |

| CDL248P | Blood | Female | UTD | 100% wt |

| CDL248P | Fibroblast | Female | UTD | 100% mut |

| CDL279P | Blood (infant) | Female | 59:41 | N/A |

| CDL317P | Blood | Female | 100:0 | 100% wt |

| CDL326AS | Blood | Female | 100:0 | N/A |

| CDL326M | Blood | Female | UTD | N/A |

| CDL326P | Blood | Male | 100 | N/A |

| CDL347P | Blood | Male | 100 | N/A |

| CDL423M | Blood | Female | 100:0 | N/A |

| CDL423P | Blood | Male | 100 | N/A |

| CDL426P | Blood | Male | 100 | 100% mut |

| CDL603P | Blood | Female | 100:1 | 100% wt |

| CDLG13952 | Blood (3 years) | Female | 8:92 | N/A |

| D11-209M | Blood | Female | 2:98 | N/A |

| DECIPHER 268420 | Blood | Female | 100:0 | N/A |

| HD8HC01P | Blood (1 year) | Female | 100:0 | N/A |

| R19E9 | Blood | Female | 95:5 | N/A |

| R19H7 | Blood | Female | 2:98 | N/A |

| R23F4 | Blood | Female | 98:2 | N/A |

| R24E11 | Blood | Female | 3:97 | N/A |

| R34B12 | Blood (15 months) | Female | 85:15 | N/A |

| R34B12 | Blood (5 years) | Female | 100:0 | N/A |

| R27C10 | Blood | Female | 1:99 | N/A |

Patient ID, source of DNA, age (in parentheses where relevant) and sex are indicated. The ratio of the activity is noted for each allele. In the allele ratio column, ‘UTD’ indicates that skewing cannot be determined due to homozygosity of the AR microsatellite allele tested. In this column, samples are shaded to indicate whether they are male (blue), female skewed toward the mutated allele (red), female skewed toward the normal allele (green), female skewed toward unknown allele (gray) or unskewed (unshaded). Note that in some familial cases (CDL326, CDL423), the determination of the wild-type and mutant alleles is inferred from an affected male family member. nd, not determined; N/A, not available; wt, wild-type allele; mut, mutated allele.

Because lymphoblastoid and fibroblast cell lines are available for only a small subset of patients, we analyzed for skewing of X-inactivation as a marker of HDAC8 allele selection in the peripheral blood. To accomplish this, we utilized a well-characterized assay that measures the methylation status of a microsatellite repeat in the 5′UTR of the androgen receptor (AR) of the inactivated X chromosome (35). For 23 heterozygous females for whom peripheral blood genomic DNA or cell lines were available, 20 were skewed >95:5, one was skewed between 95:5 and 70:30, one showed no skewing and two were uninformative due homozygous polymorphisms at the testing locus. Of note, the three samples that were skewed <95:5 were all from girls aged <4 years when the sample was obtained, which supports the hypothesis that selection of the normal allele occurs after birth.

Clinical features of individuals with HDAC8 mutations

CdLS is noted for growth, cognitive delays, limb anomalies and distinctive facial features. Of the 35 affected individuals identified in this work with mutations in HDAC8, all have clinical features that overlap those seen in CdLS, although few subjects are fully consistent with that diagnosis. Figure 2 demonstrates facial and limb findings, Supplementary Material, Table S2 details the clinical features for each individual and Table 2 demonstrates the summary of clinical findings in this cohort. The range of phenotypes was consistent with that seen for an X-linked disorder, with males being more affected. In multiplex families, we observed apparently unaffected carrier females. This sex-weighted effect is illustrated by the differences in average height, weight and head circumference between the two sexes in affected individuals (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Individuals with HDAC8 mutations. Facial features of individuals with HDAC8 mutations labeled with corresponding mutation and sex; ♂, male; ♀, female. Photos for individual patients are grouped, with the first image for each containing the type of mutation and sex, and the last image containing the subject identifier.

Table 2.

Clinical feature frequency in individuals with HDAC8 mutations

| Category | Feature | Percent (no. observed/no. assessed) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Brachycephaly | 70% (24/34) | |

| Low anterior hairline | 67% (23/34) | ||

| Skull | Prominent metopic suture (1), open/delayed fontanelles (13), asymmetry (2) | ||

| Eyes | Arched eyebrows | 88% (30/34) | |

| Synophrys | 90% (30/33) | ||

| Long eyelashes | 45% (14/31) | ||

| Hypertelorism | 47% (16/34) | ||

| Telecanthus | 64% (22/34) | ||

| Ptosis | 18% (6/32) | ||

| Myopia | 44% (11/25) | ||

| Lacrimal duct obstruction | 24% (6/25) | ||

| Hooding of lids | 46% (15/32) | ||

| Nose | Depressed nasal bridge | 45% (15/33) | |

| Anteverted nostrils | 76% (26/34) | ||

| Long philtrum | 57% (19/33) | ||

| Featureless philtrum | 30% (10/33) | ||

| Broad/bulbous nasal tip | 66% (22/33) | ||

| Mouth | Thin upper lip | 29% (10/34) | |

| Downturned corners of mouth | 57% (19/33) | ||

| Palate—high arch | 33% (7/21) | ||

| Palate—cleft | 18% (5/27) | ||

| Widely spaced teeth | 61% (16/26) | ||

| Gap between upper incisors | 50% (13/26) | ||

| Other teeth | (19) | Congenital abnormalities (10), oligodontia (3), fused (4), delayed (6) | |

| Micrognathia/retrognathia | 59% (19/32) | ||

| Short neck | 48% (12/25) | ||

| Other facial | Facial asymmetry (2), grimacing smile (1), small low-set ears (5), macrostomia (1), premature aging (1) | ||

| Skin | Cutis marmorata | 18% (5/27) | |

| Hirsutism | 65% (21/32) | ||

| Nevus flammeus | 58% (17/29) | ||

| Other skin | Pigmentary mosaicism (6), slow-growing hair and nails (1) | ||

| Hands | Small hands | 96% (28/29) | |

| Proximally set thumbs | 85% (23/27) | ||

| Clinodactyly 5th finger | 50% (14/28) | ||

| Short 5th finger | 84% (21/25) | ||

| Single Palmar crease | 20% (5/24) | ||

| Feet | Small feet | 89% (26/29) | |

| Syndactyly of toes | 44% (12/27) | ||

| Arms | Restriction of elbow movements | 4% (1/23) | |

| Other skeletal | Atypical/absent patella (2) | ||

| Cardiac | Cardiac defects | Leg asymmetry (5), Short 4/5 metacarpals, 5th fingers and distal (6), phalanges of thumbs | |

| Genitourinary | Genitourinary defects | 36% (11/30) | |

| Gastrointestinal | GER | 44% (13/29) | VUR/hydronephrosis (6), renal cysts (2), dysplasia (2), chronic disease (2), cryptorchidism or hypoplastic genitalia (5/8 males) PCOS (2) |

| Feeding problems in infancy | 67% (19/28) | ||

| GI anomalies | 86% (25/29) | ||

| Other gastrointestinal | |||

| Otolaryngologic | Hearing loss | 59% (16/27) | |

| CNS | CNS anomalies | 22% (6/27) | |

| Seizures | 28% (8/28) | ||

| Other | Hypertonia (3), hypotonia (1), gait apraxia (1) | ||

| Cognitive | Intellectual disability | 100% (30/30) | Carrier mothers not carefully evaluated |

| Behavior, personality | (23) | Autistic (3), friendly (14), hyperactive (3), aggressive (3 older), self-injurious (3) |

Clinical features are summarized by category. Percent and fractional data are indicated. Single numbers in parentheses indicate the number assessed or noted with the feature. M, male; F, female; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; GER, gastroesophageal reflux; CNS, central nervous system; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux.

Table 3.

Comparison of quantitative features between males and females with HDAC8 mutations and classical CdLS

| Parameter | HDAC8 males | HDAC8 females | Classical CdLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight | −1.7 (−3 to −0.5, n = 6) | −1.6 (−3.6 to 0, n = 21) | −1.9 (−3.0 to 0.0) |

| Birth length | −2.4 (−4 to −1, n = 5) | −1.9 (−4 to +0.5, n = 17) | −1.5 (−4.3 to +0.7) |

| Birth head circumference | −1.7 (−2.8 to −0.5, n = 2) | −1.8 (−3 to +1.5, n = 12) | −2.0 (−2.8 to −0.9) |

| Subsequent weights | −2.8 (−6.5 to −0.3, n = 7) | −1.4 (−6.5 to +3.0, n = 22) | −4.8 (−10.1 to −1.8) |

| Subsequent heights | −2.8 (−6.6 to +0.4, n = 7) | −2.0 (−4.5 to +0.4, n = 22) | −4.1 (−8.0 to −1.2) |

| Subsequent head circumference | −2.5 (−6.6 to −0.4, n = 7) | −1.9 (−5 to +1, n = 21) | −3.8 (−5.6 to −1.5) |

Growth parameters are noted at the top. Z-scores were calculated using the LMS values from 2000 United States CDC Growth Percentile Data Files (36). Data within the HDAC8 categories are presented as: (Z-score average, minimum-to-maximum range and the number or individuals with available data). Z-scores for classical CdLS data are derived from Kline et al. (37) and represents an average of both sexes at birth and 3 years for the mean and 5th–95th percentile range.

In this cohort of affected individuals, many features are quite similar to those observed in typical CdLS. These include non-specific findings such as postnatal growth retardation (28%), microcephaly (29%), hearing loss (59%), gastroesophageal reflux (67%), feeding difficulties (86%), cardiac defects (36%), genitourinary anomalies (44%) and intellectual disabilities (100%).

Many also display craniofacial features suggestive of CdLS, including brachycephaly (70%), arched eyebrows (88%), synophrys (90%), long eyelashes (45%), depressed nasal bridge (45%), anteversion of the nares (76%), long philtrum (57%), downturned corners of the mouth (57%), small widely spaced teeth (61%), micrognathia (59%) and cleft palate without cleft lip (18%). Other findings suggestive of CdLS include cutis marmorata (18%), hirsutism (65%), small hands (96%) and feet (89%), toe syndactyly (44%), verbal performance that is worse than motor performance and development of behavioral problems with age. Only one patient demonstrates a major limb anomaly.

However, several features are unique in these patients that are not seen in typical CdLS. These include delayed fontanelle closure (∼50%), ocular hypertelorism (47%) and/or telecanthus (64%), hooding or redundant overfolded skin of the upper eyelids (46%), a broad or bulbous nasal tip (66%), a prominent gap between the central incisors (50%), dental anomalies (∼50%, including oligodontia and fused incisors), nevus flammeus (58%), mosaic skin pigmentation (∼25%), limb length discrepancies in the absence of major malformations (n = 5) and happy or friendly personalities as younger children (∼50%).

Finally, several features are absent in this cohort that are commonly seen in typical CdLS. For example, the growth tends to be less disrupted with lower frequency of postnatal growth retardation (28%) and microcephaly (20%). In the face, the philtrum is often long but it is infrequently flat as in typical CdLS. In addition, the vermillion border of the upper lip tends to be thin less frequently. Only one subject has major cardiac defect, none have diaphragmatic defects and only a minority of individuals have cutis marmorata (17%), single palmar creases (20%) or restriction of elbow range of motion (4%).

DISCUSSION

Variable clinical severity caused by HDAC8 mutations

In an ongoing effort to understand the phenotypic consequences of mutations in HDAC8, we screened a broad cohort of subjects with CdLS or features that overlap the diagnosis and have sought to identify patients with HDAC8 mutations ascertained independently of a diagnosis of CdLS. In total, we have identified 38 individuals with mutations in HDAC8. These range from genomic copy number abnormalities through single nucleotide substitutions that cause missense mutations. Based on these numbers, individuals with HDAC8 mutations comprise ∼4% of patients ascertained (25 probands of 586 screened). However, the identification of HDAC8 mutations by genomic testing in seven individuals without a diagnosis of CdLS affirms that this phenotype differs from typical CdLS and may ultimately have wider ranging features than even the patients reported here. Furthermore, the severity of clinical phenotypes caused by mutations in HDAC8, especially in females, is heavily influenced by random X-inactivation. We would suspect that females with unfavorable Lyonization in the brain would display a more affected phenotype, but additional investigation would be needed to test this model.

HDAC8 mutations in CdLS cause reduced enzymatic activity

Although we have noted a range of clinical features, genetic and biochemical analysis of all HDAC8 mutations to date causing CdLS or overlapping phenotypes predict or demonstrate loss of function. Several mutations we have identified result from microdeletions or microduplications that disrupt the gene and several result from nonsense substitutions. Furthermore, enzymatic assays of all missense mutations demonstrated reduced or absent activity. This correlates with in silico mapping of the missense mutations using the known crystal structure that shows these are often located in or around residues critical for HDAC8 function. Although the numbers are quite small, there is a weak trend in males toward a milder phenotype with higher residual activity of HDAC8. However, a significant caveat exists for this observation, since this assay was performed in vitro with standardized amounts of purified HDAC8, and does not represent in vivo levels of protein. Unfortunately, we have cell lines for very few of the affected boys to determine stability of each mutation in vivo and further studies would be needed to more clearly correlate genotype and clinical severity.

Complete loss of HDAC8 function appears to be viable in humans, as evidenced by a male with a partial deletion of HDAC8 (D11–209P) and another with undetectable levels of HDAC8 protein in cells (CDL426P). This is supported by the finding that mice with a targeted null mutation can be viable, albeit at lower frequencies than wild type (38). This differs from the survivability seen for loss of other cohesin genes (39–41) in which homozygous knockouts result in embryonic lethality. This finding suggests that the endogenous function of HDAC8 may be at least partially redundant, or that other proteins, such as related deacetylases, may be upregulated to compensate for HDAC8 loss of function.

Overlapping and unique features caused by HDAC8 mutations

Although the facial features certainly overlap those of patients with typical CdLS caused by NIPBL mutations, there are notable features in individuals with HDAC8 mutations. Several of the most distinct likely derive from an abnormality of skull formation. Quite notably, this effect is directly comparable with the Hdac8 mouse knockout, which demonstrates extreme growth failure and markedly delayed closure of skull sutures (38). In a large percentage of individuals with HDAC8 mutations, delayed, sometimes marked, closure of the anterior fontanelle has been observed. We hypothesize that this effect represents an embryonic anomaly that results in delayed development of midline structures of the face to result in hypertelorism, telecanthus and/or forehead nevus flammeus. Furthermore, several additional facial features, including hooding of eyelids and dental anomalies, are distinctive in this cohort. These findings, in combination with a more well-formed philtrum and upper lip, suggest that the face may be useful in defining a clinically recognizable subgroup of individuals. While all affected cases demonstrate some dysmorphic facial features, there is a significant diversity of facial appearance within the HDAC8-mutated subjects. This diversity may reflect level of mutation load in the embryonic face (in the context of unaffected mothers) or an evolving phenotype with age. However, it may also provide clues to domain-specific functions of the protein.

Of note, a family was recently reported by Harakalova et al. (26), in which affected males demonstrate intellectual disability, truncal obesity, hypogonadism and distinctive facial features caused by a splice site mutation in HDAC8. This family does not demonstrate facial features or a body build of typical CdLS, suggesting that the mechanism of this mutation may differ from that for cases of CdLS initially noted with HDAC8 mutations (25). In support of this, our cohort had only three individuals for whom obesity was a significant feature. However, several of the boys reported by Harakalova et al. (26) demonstrate some weak similarity with hooding of the eyelids and arched eyebrows. In combination with the wide range of phenotypes seen in our cohort, it is possible that this family represents another instance of an emerging spectrum of phenotypes caused by HDAC8 mutations. Further analysis of the mutation identified in this family and the role of HDAC8 in growth and metabolism will be useful to help further understand these observations.

Updated clinical diagnostic approach for CdLS

Based on genotype–phenotype correlations, we currently recommend the following diagnostic approach for patients with features suggestive of CdLS due to atypical growth, cognition, facies or limbs. For those with classical facial features, NIPBL should be assessed first, preferably in buccal or skin cells as suggested by Huisman et al. (8). If a multiple cohesin gene panel is not available and the facial features are atypical, X-inactivation studies may be useful. In the setting of atypical facies, a wide fontanelle, hooding of the eyelids and/or heavily skewed X-inactivation studies, HDAC8 assessment would be increased in priority. For those with atypical features that include broader fuller less arched eyebrows or a broader nasal tip, SMC1A, and perhaps SMC3, assessment would be higher priority than HDAC8 (14). If the above testing is negative, RAD21 should be considered. As exome sequencing coverage increases, exome-based exon-level copy number analysis improves, and the cost of exome sequencing falls, it will become reasonable to consider exome sequencing as first line testing for this heterogenous disorder.

Unique clinical recommendations for these patients

For patients in whom an HDAC8 mutation is suspected or identified, we would include a workup similar to patients with a diagnosis of classical CdLS (42,43), which typically includes cardiac, renal and gastroenterologic studies, palate evaluation, hearing studies, speech, physical and occupational therapy assessments, molecular studies to confirm a diagnosis, and assessment of platelet levels and immune function. In addition, a careful maternal family history should be assessed and molecular testing of all mothers of children for whom HDAC8 mutations have been found should be considered. If a high suspicion of an HDAC8 mutation exists but none is identified, X-inactivation studies could help to increase or decrease suspicion of a mutation in the region.

In conclusion, mutations in HDAC8 comprise ∼4% of mutations in individuals with features suggestive of CdLS and result in an atypical clinical phenotype that has elements of overlap with patients harboring NIPBL mutations. However, in general, there are several exceptions to the phenotypic similarity that include wide skull fontanelles, hooded eyelids, a slightly broader nasal base and a notably pleasant personality. This work emphasizes the role of acetylation of non-histone targets in human development and stresses the need for additional studies to understand the mechanism of cohesin regulation in the context of human developmental disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

All individuals in this study were diagnosed by clinical geneticists to have clinical features consistent with or overlapping a diagnosis of CdLS or were found to have HDAC8 mutations identified by genome-wide analyses. All subjects and family members were enrolled in the study under an institutionally approved protocol of informed consent at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the Institut für Humangenetik Lübeck or the UK (Scotland A) MREC Committee. All probands ascertained as CdLS were previously screened and found negative for mutations in NIPBL and SMC1A. Most were previously screened for mutations in SMC3, RAD21 and other cohesin genes. Subjects with HDAC8 mutations found by genome-wide methods were enrolled following their identification.

Mutation screening

The coding exons and intron–exon boundaries of HDAC8 were amplified by PCR of genomic DNA and Sanger sequenced. Primers were designed using ExonPrimer (http://ihg.gsf.de/ihg/ExonPrimer.html) (44). Primer sequences and PCR conditions (25) are available upon request. Sequencing was performed using BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing and analyzed on an ABI 3730 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Genome-wide copy number analysis

Whole-genome SNP genotyping was performed using Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) Infinium HumanHap550 or Omni 1 M Beadchip or Affymetrix (Fremont, CA, USA) Genome-Wide Human SNP 6.0 arrays according to the manufacturer's protocols. Copy number calling was performed using published algorithms (45) and PennCNV (46). Inspection of copy number variants was performed for Xq13.1 by analyzing allele frequency and log R ratio values using Illumina BeadStudio (ver. 3.1.3) or Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite (version 1.0) software as described (47). For case R19H7, genome-wide analysis of DNA copy number aberrations was carried out using the Roche Nimblegen 3 × 720K whole-genome array (median probe spacing of ∼2 kb) according to the manufacturer's instructions, modified as follows: 500 ng of genomic DNA from patient and sex-matched control samples (pool of five samples) was labeled for 2h followed by hybridization for 72 h. After washing, slides were scanned using the Roche MS200 scanner, and analyzed using the software NimbleScan (Roche Nimblegen). The CGH-segMNT module of NimbleScan was used for the analysis with a minimum segment length of five probes and an averaging window of 20 kb.

Exome sequencing

Exome capture and sequencing was performed in several clinically validated diagnostic labs. Subject HD8HC01P exome sequencing and copy number analysis were performed using the UW CMG CoNIFER pipeline (48).

Reference sequences and HDAC8 conservation analysis

HDAC8 accession numbers used to include NM_018486.2 (mRNA), NP_060956 (RefSeq protein) and Q9By41 (UniProt). HDAC8 protein sequences for human (AAF73428), Bos taurus (DAA12953), rat (AAI62023), mouse (CAM17598), Danio rerio (NP_998596), Xenopus laevis (NP_001085711), Xenopus tropicalis deduced from mRNA BC161282, Drosophila melanogaster (AAC61494) and for Saccharomyces cerevisiae HDAC8-like proteins, HOS1 (Q12214) and RPD3 (AAT92832) were aligned by the ClustalW method (49) using MacVector software (Accelrys Corp, San Diego, CA, USA).

Mapping mutations to HDAC8 structure

Identified HDAC8 mutations were mapped onto the crystal structure data of human HDAC8-substrate complex (PDB accession code 2V5W) (27) to visualize location with respect to the enzyme active site using Cn3D (50) and PyMol (51) software.

Recombinant HDAC8 purification from E. coli

Missense human HDAC8 mutations were introduced into a previously described HDAC8–6His-pET20b construct (30) using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Genomics, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Oligonucleotide sequences are available upon request. Recombinant wild-type HDAC8 and mutants I19S, H42P, H71Y, P91L, G117E, C153F, H180R, A188 T, D233G, D237Y, ΔK239-Y240N, I243N, G304R, T311M, G320R and H334R were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and purified according to a previously published procedure (30), with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 ml cultures (LB media supplemented with 100 µg/l ampicillin) were grown overnight and used to inoculate 1 l flasks (minimal media supplemented with 100 µg/l ampicillin). Typically, 2–6 l were expressed for each mutant. Cells were grown at 37°C until OD600 ∼0.5, at which point the temperature was lowered to 18°C. After 30 min, cells were induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.4 mm final concentration) and zinc chloride (100 µm final concentration), and grown overnight at 18°C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation and kept at −80°C until purification. After thawing, cells were resuspended in ∼ 30 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mm KCl, 5% glycerol, 3 mm β-mercaptoethanol (BME) and 115 µm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride), and lysed by sonication on ice. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was purified by affinity chromatography (Talon resin, Clontech Labs) using an imidazole gradient. After loading the cell-free extract in buffer A (50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mm KCl, 5% glycerol, 3 mm BME), the column was washed with 4% buffer B (50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mm KCl, 250 mm imidazole, 5% glycerol, 3 mm BME) and the protein was eluted with a 4–80% linear gradient of buffer B. Fractions containing the protein were pooled and concentrated to ∼ 500 µl by ultrafiltration. The protein was then dialyzed at 4°C against buffer C (50 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mm KCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol). Protein concentrations were determined from the absorbance using a calculated extinction coefficient: 50 240 m−1cm−1 for the wild type and all the mutants except H71Y (51 520 m−1cm−1), C153F (50 180 m−1cm−1), D237Y (51 520 m−1cm−1) and ΔK239-Y240N (48 960 m−1cm−1) (52). The H42P mutant did not express a soluble protein under these conditions.

HDAC8 activity assays

Enyzmatic activity of purified proteins was measured using the commercially available Fluor-de-Lys HDAC8 deacetylase substrate (BML-KI178-0005) and Developer II (BML-KI176-1250) from Enzo Life Sciences. In this assay, deacetylation of the tetrapeptide substrate (acetyl)-l-Arg-l-His-l-Lys(ε-acetyl)-l-Lys(ε-acetyl)-aminomethylcoumarin allows a protease developer to cleave the amide bond linking the C-terminal aminomethylcoumarin to the peptide backbone, which results in a fluorescence shift. All assays were run at 25°C in assay buffer (25 mm Tris (pH = 8.2), 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2) and contained 150 µm substrate with the following enzyme concentrations: 0.5 µm (wild type, P91L, H334R), 1.0 µm (A188 T), 1.5 µm (I19S, I243N, D233G, D237Y, G320R), 2.5 µm (H71Y, G117E, H180R, ΔK239-Y240N, G304R, T311M) or 3 µm (C153F) enzyme. After 30 min, reactions were quenched by the addition of the HDAC8 inhibitor M344 (Sigma-Aldrich, 100 µm) and Developer II. The fluorescence of both remaining substrate and formed product was measured using a Fluoroskan II plate reader (excitation = 355 nm, emission = 460 nm). Product concentration was calculated from raw data using standard curves for substrate and product (Aminomethylcoumarin, Enzo Life Sciences), with the total concentration of substrate and product kept at 150 µm (before dilution with the developer solution). All assays were performed in triplicate.

Tissue culture

Lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented to 20% FBS and 2% 20 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. HeLa cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented to 10% FBS. Nonsense-mediated decay was inhibited using 1 mg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in culture media for 6 h prior to harvesting RNA.

Assessment of X-inactivation

X chromosome inactivation (XCI) was determined by evaluating the methylation status of the CAG microsatellite locus at the 5′ end of the AR gene as previously described with modifications (35,53). Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood or cell lines and for each sample, two reaction digests were performed. In one reaction, 1 μg of DNA was digested in 25 μl with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII (New England Biolabs), to cut the active unmethylated allele. In the other reaction, DNA was incubated in enzyme digest buffer without enzyme. After a 16 h incubation at 37°C, digestion was terminated by incubation at 65°C for 20 min. From each reaction, 2 μl was then amplified by PCR with primers flanking the polymorphic androgen-receptor CAG repeat as described (35); forward 5′-CTGTGAAGGTTGCTGTTCCTCAT-3′; reverse 5′-FAM-TCCAGAATCTGTTCCAGAGCGTGC-3′). ABI3730 Genetic Analyzer and GeneMapper V4.0 software (Applied Biosystems) was used for genotyping analysis. Percent X-inactivation was calculated by dividing the ratio of the allele peak volumes in the HpaII-treated by the ratio of the allele peak volumes in the untreated sample. We considered alleles separated by more than two trinucleotide repeats as informative (54) and used a cutoff of >80:20% for skewed XCI and >95:5% for extremely skewed XCI.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (NICHD K08HD055488 to, M.A.D., (GM49758 to D.W.C., NICHD P01 HD052860 to I.D.K.; research grants from the USA CdLS Foundation; the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to M.A.D.; institutional funds from the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; the Roy & Diana Vagelos Scholars Program in Molecular Life Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania; intramural funding from the University of Lübeck (Schwerpunktprogramm, Medizinische Genetik: Von seltenen Varianten zur Krankheitsentstehung) to F.J.K.; the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (B.M.B.F.) under the frame of E-Rare-2 (TARGET-CdLS to F.J.K.); the ERA-Net for Research on Rare Diseases, Research Program of Innovative Cell Biology by Innovative Technology and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research to K.S.; the Region of Tuscany to A.M.; the UK Medical Research Council to D.R.F. and M.A.; the Spanish Ministry of Health Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) [PI12/01318]; the Diputación General de Aragón (Grupo Consolidado B20); CIBERER (GCV-HCULB Zaragoza); the European Social Fund to J.P.; the Australian Research Council to M.B., the National Health and Medical Research Council to M.B., the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program, as well as Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council IRIISS support to M.B. and P.D. Sequencing was provided by the University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics (UW CMG) and was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant (1U54HG006493 to Drs Debbie Nickerson, Jay Shendure and Michael Bamshad). Work was performed under the FORGE Canada and Care4Rare Canada Consortiums funded by Genome Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Ontario Genomics Institute (OGI-049), Ontario Research Fund, Genome Quebec, Genome British Columbia and CHEO Foundation.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

F.J.K, G.G.-K., R.H., J.W., F.J.R, L.G.J., J.P., D.R.F, I.D.K. and M.A.D initiated the human studies. D.J.A., P.S.A., H.G.B., D.C., M.dC.-C, N.D., H.D., J.C.F, E.G.-N., Y.G., B.D.H., R.H., L.H., H.I., A.D.K., Z.K., K.L., S.A.L., G.R.M., S.G.M., I.M., S.M., E.M., G.R.M., L.N., A.P.-A., L.S.P., M.B.P., A.P., B.P., F.Q.-R., N.R., E.R., S.S., A.E.S., K.L.S., V.M.S., Z.S., H.T., P.W., K.W., L.W., J.W., A.M., G.G.-K., F.J.R., L.G.J., J.P., I.D.K., D.R.F. and M.A.D. identified, characterized and provided patient data and samples. F.J.K., M.A., M.C.G.-R., M.K., M.B., J.J.B., P.D., J.E., S.E., L.F. M.H., J.H., H.L., L.M., F.Q.-R., S.P.S., I.V., UWCMD, H.H., D.R.F., I.D.K. and M.A.D. performed array analysis, mutation screening, exome analysis and/or inactivation studies. C.D., J.W., C.F., M.B., C.M.B., M.B.M., J.S.M., N.N., K.S., D.W.C. and M.A.D. performed enzymatic and structural analysis. F.J.K., D.R.F. and M.A.D. drafted the manuscript. All authors analyzed data, discussed the results and were provided opportunity to comment on the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are exceptionally grateful to the patients and families who participated in this study as well as to the referring physicians and colleagues who have contributed samples and clinical information. We are indebted to the continued support of the USA and International Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Foundations. We acknowledge the contribution of the University of California Los Angeles Clinical Genomics Center Genomic Data Board members who have not otherwise been included in the authorship; Drs Kingshuk Das, Joshua Deignan, Naghmeh Dorrani, Sibel Kantarci, Eric Vilain, Stanley F. Nelson and Wayne W. Grody.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhuiyan Z., Klein M., Hammond P., Mannens M.M., Van Haeringen A., Van Berckelaer-Onnes I., Hennekam R.C. Genotype–phenotype correlations of 39 patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome: the Dutch experience. J. Med. Genet. 2005;43:568–575. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.038240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillis L.A., McCallum J., Kaur M., DeScipio C., Yaeger D., Mariani A., Kline A.D., Li H.H., Devoto M., Jackson L.G., et al. NIPBL mutational analysis in 120 individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome and evaluation of genotype-phenotype correlations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:610–623. doi: 10.1086/424698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krantz I.D., McCallum J., DeScipio C., Kaur M., Gillis L.A., Yaeger D., Jukofsky L., Wasserman N., Bottani A., Morris C.A., et al. Cornelia de Lange syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:631–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonkin E.T., Wang T.J., Lisgo S., Bamshad M.J., Strachan T. NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:636–641. doi: 10.1038/ng1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan J., Saifi G.M., Wierzba T.H., Withers M., Bien-Willner G.A., Limon J., Stankiewicz P., Lupski J.R., Wierzba J. Mutational and genotype-phenotype correlation analyses in 28 Polish patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:1531–1541. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selicorni A., Russo S., Gervasini C., Castronovo P., Milani D., Cavalleri F., Bentivegna A., Masciadri M., Domi A., Divizia M.T., et al. Clinical score of 62 Italian patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome and correlations with the presence and type of NIPBL mutation. Clin. Genet. 2007;72:98–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pie J., Gil-Rodriguez M.C., Ciero M., Lopez-Vinas E., Ribate M.P., Arnedo M., Deardorff M.A., Puisac B., Legarreta J., de Karam J.C., et al. Mutations and variants in the cohesion factor genes NIPBL, SMC1A, and SMC3 in a cohort of 30 unrelated patients with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:924–929. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huisman S.A., Redeker E.J., Maas S.M., Mannens M.M., Hennekam R.C. High rate of mosaicism in individuals with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2013;50:339–344. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollins R.A., Morcillo P., Dorsett D. Nipped-B, a Drosophila homologue of chromosomal adherins, participates in activation by remote enhancers in the cut and Ultrabithorax genes. Genetics. 1999;152:577–593. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciosk R., Shirayama M., Shevchenko A., Tanaka T., Toth A., Nasmyth K. Cohesin's binding to chromosomes depends on a separate complex consisting of Scc2 and Scc4 proteins. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:243–254. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillespie P.J., Hirano T. Scc2 couples replication licensing to sister chromatid cohesion in Xenopus egg extracts. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1598–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi T.S., Yiu P., Chou M.F., Gygi S., Walter J.C. Recruitment of Xenopus Scc2 and cohesin to chromatin requires the pre-replication complex. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2004;6:991–996. doi: 10.1038/ncb1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasmyth K., Haering C.H. Cohesin: its roles and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohatgi S., Clark D., Kline A.D., Jackson L.G., Pie J., Siu V., Ramos F.J., Krantz I.D., Deardorff M.A. Facial diagnosis of mild and variant CdLS: insights from a dysmorphologist survey. Am. J. Med. Genet. A, 152A. 2010:1641–1653. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musio A., Selicorni A., Focarelli M.L., Gervasini C., Milani D., Russo S., Vezzoni P., Larizza L. X-linked Cornelia de Lange syndrome owing to SMC1L1 mutations. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:528–530. doi: 10.1038/ng1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deardorff M.A., Kaur M., Yaeger D., Rampuria A., Korolev S., Pie J., Gil-Rodriguez C., Arnedo M., Loeys B., Kline A.D., et al. Mutations in cohesin complex members SMC3 and SMC1A cause a mild variant of Cornelia de Lange syndrome with predominant mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:485–494. doi: 10.1086/511888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deardorff M.A., Wilde J.J., Albrecht M., Dickinson E., Tennstedt S., Braunholz D., Monnich M., Yan Y., Xu W., Gil-Rodriguez M.C., et al. RAD21 mutations cause a human cohesinopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:1014–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J., Shi X., Li Y., Kim B.J., Jia J., Huang Z., Yang T., Fu X., Jung S.Y., Wang Y., et al. Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is required for S phase sister chromatid cohesion in both human and yeast. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolef Ben-Shahar T., Heeger S., Lehane C., East P., Flynn H., Skehel M., Uhlmann F. Eco1-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1157774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unal E., Heidinger-Pauli J.M., Kim W., Guacci V., Onn I., Gygi S.P., Koshland D.E. A molecular determinant for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1157880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutani T., Kawaguchi T., Kanno R., Itoh T., Shirahige K. Budding yeast Wpl1(Rad61)-Pds5 complex counteracts sister chromatid cohesion-establishing reaction. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckouet F., Hu B., Roig M.B., Sutani T., Komata M., Uluocak P., Katis V.L., Shirahige K., Nasmyth K. An Smc3 acetylation cycle is essential for establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong B., Lu S., Gerton J.L. Hos1 is a lysine deacetylase for the Smc3 subunit of cohesin. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1660–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges V., Lehane C., Lopez-Serra L., Flynn H., Skehel M., Rolef Ben-Shahar T., Uhlmann F. Hos1 deacetylates Smc3 to close the cohesin acetylation cycle. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deardorff M.A., Bando M., Nakato R., Watrin E., Itoh T., Minamino M., Saitoh K., Komata M., Katou Y., Clark D., et al. HDAC8 mutations in Cornelia de Lange syndrome affect the cohesin acetylation cycle. Nature. 2012;489:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harakalova M., van den Boogaard M.J., Sinke R., van Lieshout S., van Tuil M.C., Duran K., Renkens I., Terhal P.A., de Kovel C., Nijman I.J., et al. X-exome sequencing identifies a HDAC8 variant in a large pedigree with X-linked intellectual disability, truncal obesity, gynaecomastia, hypogonadism and unusual face. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:539–543. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vannini A., Volpari C., Gallinari P., Jones P., Mattu M., Carfi A., De Francesco R., Steinkuhler C., Di Marco S. Substrate binding to histone deacetylases as shown by the crystal structure of the HDAC8-substrate complex. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:879–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D.F., Helquist P., Wiech N.L., Wiest O. Toward selective histone deacetylase inhibitor design: homology modeling, docking studies, and molecular dynamics simulations of human class I histone deacetylases. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6936–6947. doi: 10.1021/jm0505011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haider S., Joseph C.G., Neidle S., Fierke C.A., Fuchter M.J. On the function of the internal cavity of histone deacetylase protein 8: R37 is a crucial residue for catalysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2129–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowling D.P., Gantt S.L., Gattis S.G., Fierke C.A., Christianson D.W. Structural studies of human histone deacetylase 8 and its site-specific variants complexed with substrate and inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13554–13563. doi: 10.1021/bi801610c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wegener D., Hildmann C., Riester D., Schwienhorst A. Improved fluorogenic histone deacetylase assay for high-throughput-screening applications. Anal. Biochem. 2003;321:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lombardi P.M., Cole K.E., Dowling D.P., Christianson D.W. Structure, mechanism, and inhibition of histone deacetylases and related metalloenzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011;21:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somoza J.R., Skene R.J., Katz B.A., Mol C., Ho J.D., Jennings A.J., Luong C., Arvai A., Buggy J.J., Chi E., et al. Structural snapshots of human HDAC8 provide insights into the class I histone deacetylases. Structure. 2004;12:1325–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cole K.E., Dowling D.P., Boone M.A., Phillips A.J., Christianson D.W. Structural basis of the antiproliferative activity of largazole, a depsipeptide inhibitor of the histone deacetylases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12474–12477. doi: 10.1021/ja205972n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen R.C., Zoghbi H.Y., Moseley A.B., Rosenblatt H.M., Belmont J.W. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:1229–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuczmarski R.J., Ogden C.L., Guo S.S., Grummer-Strawn L.M., Flegal K.M., Mei Z., Wei R., Curtin L.R., Roche A.F., Johnson C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kline A.D., Barr M., Jackson L.G. Growth manifestations in the Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993;47:1042–1049. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haberland M., Mokalled M.H., Montgomery R.L., Olson E.N. Epigenetic control of skull morphogenesis by histone deacetylase 8. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1625–1630. doi: 10.1101/gad.1809209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawauchi S., Calof A.L., Santos R., Lopez-Burks M.E., Young C.M., Hoang M.P., Chua A., Lao T., Lechner M.S., Daniel J.A., et al. Multiple organ system defects and transcriptional dysregulation in the Nipbl(+/−) mouse, a model of Cornelia de Lange syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu H., Balakrishnan K., Malaterre J., Beasley M., Yan Y., Essers J., Appeldoorn E., Tomaszewski J.M., Vazquez M., Verschoor S., et al. Rad21-cohesin haploinsufficiency impedes DNA repair and enhances gastrointestinal radiosensitivity in mice. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remeseiro S., Cuadrado A., Carretero M., Martinez P., Drosopoulos W.C., Canamero M., Schildkraut C.L., Blasco M.A., Losada A. Cohesin-SA1 deficiency drives aneuploidy and tumourigenesis in mice due to impaired replication of telomeres. EMBO J. 2012;31:2076–2089. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kline A.D., Krantz I.D., Sommer A., Kliewer M., Jackson L.G., FitzPatrick D.R., Levin A.V., Selicorni A. Cornelia de Lange syndrome: clinical review, diagnostic and scoring systems, and anticipatory guidance. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143:1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deardorff M.A., Clark D.M., Krantz I.D. In GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (Database Online) University of Washington, Seattle, in press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strom T. 2006 ExonPrimer (database online) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaikh T.H., Gai X., Perin J.C., Glessner J.T., Xie H., Murphy K., O'Hara R., Casalunovo T., Conlin L.K., D'Arcy M., et al. High-resolution mapping and analysis of copy number variations in the human genome: a data resource for clinical and research applications. Genome Res. 2009;19:1682–1690. doi: 10.1101/gr.083501.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K., Li M., Hadley D., Liu R., Glessner J., Grant S.F., Hakonarson H., Bucan M. PennCNV: an integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peiffer D.A., Le J.M., Steemers F.J., Chang W., Jenniges T., Garcia F., Haden K., Li J., Shaw C.A., Belmont J., et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of chromosomal aberrations using Infinium whole-genome genotyping. Genome Res. 2006;16:1136–1148. doi: 10.1101/gr.5402306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krumm N., Sudmant P.H., Ko A., O'Roak B.J., Malig M., Coe B.P., Project N.E.S., Quinlan A.R., Nickerson D.A., Eichler E.E. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eddy S.R. Multiple alignment using hidden Markov models. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1995;3:114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Geer L.Y., Chappey C., Kans J.A., Bryant S.H. Cn3D: sequence and structure views for Entrez. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:300–302. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jessberger R. The many functions of SMC proteins in chromosome dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3:767–778. doi: 10.1038/nrm930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill S.C., von Hippel P.H. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Sutton V.R., Omar Peraza-Llanes J., Yu Z., Rosetta R., Kou Y.C., Eble T.N., Patel A., Thaller C., Fang P., et al. Mutations in X-linked PORCN, a putative regulator of Wnt signaling, cause focal dermal hypoplasia. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:836–838. doi: 10.1038/ng2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amos-Landgraf J.M., Cottle A., Plenge R.M., Friez M., Schwartz C.E., Longshore J., Willard H.F. X chromosome-inactivation patterns of 1,005 phenotypically unaffected females. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:493–499. doi: 10.1086/507565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.