Abstract

Abstract: Stabilin-1 is an endocytotic scavenger receptor, specifically expressed by non-continuous sinusoidal endothelial cells in the liver, spleen and lymph nodes and by M2 or alternatively activated macrophages in human malignancies. We analysed paraffin-embedded tissue of melanocytic lesions and granulomatous diseases for stabilin-1 expression, using the human/murine RS1 antibody. The specificity of the RS1 staining was confirmed in a knockout model, as only M2-like tumor-associated macrophages and vessels of a B16F10 melanoma in wild type mice stained positive; while staining of tumor-associated macrophages and vessels originating from stabilin-1 deficient mice remained negative for stabilin-1 specific antibody RS1. In human specimens, the RS1 antibody stained tumor-associated macrophages in all pathological stages of melanoma. In addition, five cases of juvenile xanthogranulomas and one case of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma were strongly stabilin-1 positive, while Th-1 cytokine dominated granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis and granulomatous leprosy were negative. Stabilin-1 positive vessels were found in all analysed non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses and melanocytic lesions. No stabilin-1 positive vessels were present in any other granulomatous diseases.

Keywords: Melanoma, melanocytic nevus, xanthogranuloma, tumor associated macrophages, tumor classification, M2 macrophages, marker molecules

Introduction

Human stabilin-1 is a 280 kDa type I transmembrane protein, with a small cytoplasmic domain at the C-terminus, a single transmembrane domain and a large extracellular part; which contains 7 fasciclin domains, 18 epithelial growth factor domains and a single X-link domain. Stabilin-1 was originally identified as the high molecular weight protein antigen of the human specific antibody, MS-1 [1]. The MS-1 antibody detects non-continuous sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow, as well as macrophage-like cells in human organs. In vitro, the MS-1 antigen was strongly expressed by alternatively activated macrophages; a special subtype of macrophage associated with functions in wound healing and angiogenesis [2]. Under pathologic conditions in humans, stabilin-1 expression has been localized to endothelial cells of continuous origin, like wound healing tissue, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, psoriasis and melanoma metastasis [3]. As the MS-1 antibody is limited to frozen sections, no systematic analysis allowing the correlation of stabilin-1 positive vessel or macrophage density to diagnostic parameters in human pathologies has been performed so far.

On a functional level, stabilin-1 is described as an endocytic clearance receptor expressed on sinusoidal endothelial cells, as well as alternatively activated (M2) macrophages. Known external stabilin-1 ligands comprise placental lactogen [4], the secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) [5], oxidized low-density lipoprotein [6] and heparin [7]. Although stabilin-1 ligands harbor potent physiological effects (e.g. angiogenesis and immune stimulation) and a link between stabilin-1 expression, and downstream effects mediated by stabilin-1 ligands have been discussed intensively [8], a physiological relevance of stabilin-1 in pathologies remains speculative. However, a stabilin-1 and -2 double knockout mouse model displayed a phenotype of glomerular sclerosis and mild liver fibrosis [9]. The homologous protein stabilin-2 is expressed exclusively by non-continuous endothelial cells, and it shares a sequence homology with stabilin-1 of about 56% on amino acid level [10].

Several stabilin-1 directed novel antibodies have been generated either commercially or by research groups [4,11-14]. One of these is the rabbit polyclonal antibody RS1, which is directed against the C-terminal part of human stabilin-1. This antibody detects stabilin-1 not only in frozen sections, but also in paraffin embedded material, required for a systematic, tissue bank based analysis of human specimens. In addition, RS1 was found to recognize murine stabilin-1.

Here, we analyzed the expression of stabilin-1 in paraffin-embedded melanocytic lesions and granulomatous skin diseases of humans. A systematic analysis of melanocytic lesions revealed a substantial infiltration of stabilin-1+ macrophages in nevi, as well as in melanomas. In addition, all analyzed non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses were stabilin-1 positive; while Th-1 cytokine dominated granulomatous diseases such as granulomatous leprosy, granuloma annulare and sarcoidosis stained negative or only partially positive. In terms of vascular structures, stabilin-1 expression were found only in human melanocytic nevi, melanomas and non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses, in contrast, vessels of other analyzed granulomatous diseases of the skin remained stabilin-1 negative.

Materials and methods

Case materials

The study was performed in accordance with federal laws and regulations and institutional policies. We obtained ethical approval of the local ethical committee (Medical Ethic Commission II, Faculty of Medicine Mannheim, University of Heidelberg in Germany) filed under the reference number: 2010-318N-MA. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and data was analysed anonymously. Pathological cases were identified using an electronic database and retrieved from the pathology tissue archives of the University Medical Center Mannheim. All juvenile and necrobiotic xanthogranulomas, tuberous xanthomas and granulomatous leprosy diagnosed after January 2000 were included in the study. A total of 5 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 8 cases of granuloma annulare, 6 cases of melanocytic nevi and 14 cases of melanomas were included in the study.

Murine tumor models

C57BL/6 wild type mice were purchased from Janvier Labs, Le Genest Saint Isle, France. C57BL/6 stabilin-1 knockout mice were bred in animal facility of the Faculty of Medicine Mannheim as described [9]. All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at the animal facility in Mannheim. To generate experimental B16F10 tumors, 1 x 106 tumor cells (B16F10 [ATCC CRL-6475], purchased from LGC Standards, Wesel, Germany) were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of 12 week-old female C57BL/6 wild type mice and female C57BL/6 stabilin-1 knockout mice. After 21 days, the animals were sacrificed and the tumor samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The animal experimental protocols were approved by the animal ethics committee (Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe, Germany, Az: 35-9185.81/G-208/10).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical studies of the human tissue were performed on 2 μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples using series graded alcohol for deparaffinization and heat induced epitope retrieval. CD68 was stained using a commercial antibody (1:300) (PG-M1, Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Stabilin-1 was stained using a custom-made rabbit anti-mouse/human stabilin-1 antibody (RS1) (1:1000) (PSL GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), followed by the appropriated horseradish peroxidase labeled secondary antibody as described [4]. All samples were analyzed by light-microscopy using a Leica DCRE microscope with Leica DC500 camera and software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

The immunohistochemical stainings of subcutaneous B16F10 tumors of C57BL/6 wild type and C57BL/6 stabilin-1 knockout mice were performed on 7 μm acetone-fixed cryosections using the same RS1 antibody (1:1000). To classify stabilin-1 positive structures cryosections were double stained with either rat anti-mouse CD68 (1:400) (MCS1957GA, ABD Serotec, Puchheim, Germany) or rat anti-mouse CD31 (1:300) (MCA2388, ABD Serotec) and subsequently, fluorescent secondary antibodies goat anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:300) (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and goat anti-rat Alexa 488 (1:400) (Dianova). The samples were analysed by confocal microscopy as described [4,15].

Scoring

For the quantification of CD68+ and stabilin-1+ macrophages and stabilin-1+ vessels in all analysed diseases, the amount of positively stained cells/vessels in three independent representative areas (400x magnification) were counted by two researchers (A.S. and K.S.). The results are shown as mean ± SEM and listed in the Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Stabilin-1/CD68 expression in melanoma - associated macrophages and vessels

| Patient ID | Age at diagnosis [Year] | Sex | Year of diagnosis | Tumour localization | Breslow index [mm] | PT stage (AJCC 2009) | TNM classification (AJCC 2009) | Sentinel lymph node | Stabilin-1 in CD68+ macrophages [%] | Stabilin-1+ vessels [%] | CD68 expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73 | M | 2013 | Shoulder | 0.45 | pT1a | IA | N/A | 14.4 | 0 | 39.7 |

| 2 | 56 | M | 2008 | Back | 0.6 | pT1b | IB | N/A | 91.3 | 13.3 | 82.3 |

| 3 | 59 | M | 2010 | Abdomen | 0.4 | pT1b | IB | Negative | 95.7 | 18.0 | 15.7 |

| 4 | 48 | M | 2013 | Shoulder | 1.9 | pT2a | IB | Negative | 7.9 | 6.7 | 121.3 |

| 5 | 78 | M | 2013 | Cheek | 1.3 | pT2a | IB | N/A | 89.2 | 0.0 | 55.7 |

| 6 | 23 | F | 2013 | Heel | 1.5 | pT2a | IB | Negative | 2.1 | 25.7 | 96.3 |

| 7 | 77 | M | 2010 | Back | 1.75 | pT2b | IIA | Negative | 33.1 | 34.7 | 70.3 |

| 8 | 56 | F | 2010 | Foot | 3.1 | pT3a | IIA | Negative | 56.3 | 67.3 | 23.3 |

| 9 | 61 | M | 2013 | Back | 2.2 | pT3a | IIA | Negative | 13.2 | 0 | 75.3 |

| 10 | 80 | M | 2011 | Arm | 3.9 | pT3a | IIIA | Positive | 35.3 | 43.3 | 39.0 |

| 11 | 58 | M | 2009 | Back | 3.0 | pT3b | IIIC | Negative | 42.9 | 8.0 | 57.3 |

| 12 | 48 | M | 2009 | Ankle | 4.1 | pT4a | IIIA | Postive | 12.2 | 26.7 | 241.3 |

| 13 | 103 | M | 2013 | Forehead | 5.25 | pT4b | IIC | N/A | 31.0 | 22.7 | 38.3 |

| 14 | 78 | M | 2008 | Temple | 9.0 | pT4b | IV | N/A | 62.5 | 39.3 | 131.7 |

Table 2.

Stabilin-1/CD68 expression in nevus- associated macrophages and vessels

| Patient ID | Age at diagnosis [Year] | Sex | Year of diagnosis | Diagnosis | Stabilin-1 in CD68+ macrophages [%] | Stabilin-1+ vessels [%] | CD68 expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | M | 2013 | Compound nevus | 98.3 | 21.0 | 39.7 |

| 2 | 76 | M | 2013 | Compound nevus | 84.8 | 0 | 31.3 |

| 3 | 33 | F | 2013 | Compound nevus | 24.1 | 11.0 | 31.0 |

| 4 | 76 | M | 2013 | Compound nevus | 62.6 | 11.3 | 42.3 |

| 5 | 30 | F | 2012 | Irritated papillomatous compound nevus | 92.6 | 40.0 | 34.3 |

| 6 | 30 | F | 2012 | Junctional nevus | 59.6 | 20.0 | 42.7 |

Results

Stabilin-1 is expressed in macrophages and several vessels of melanocytic lesions

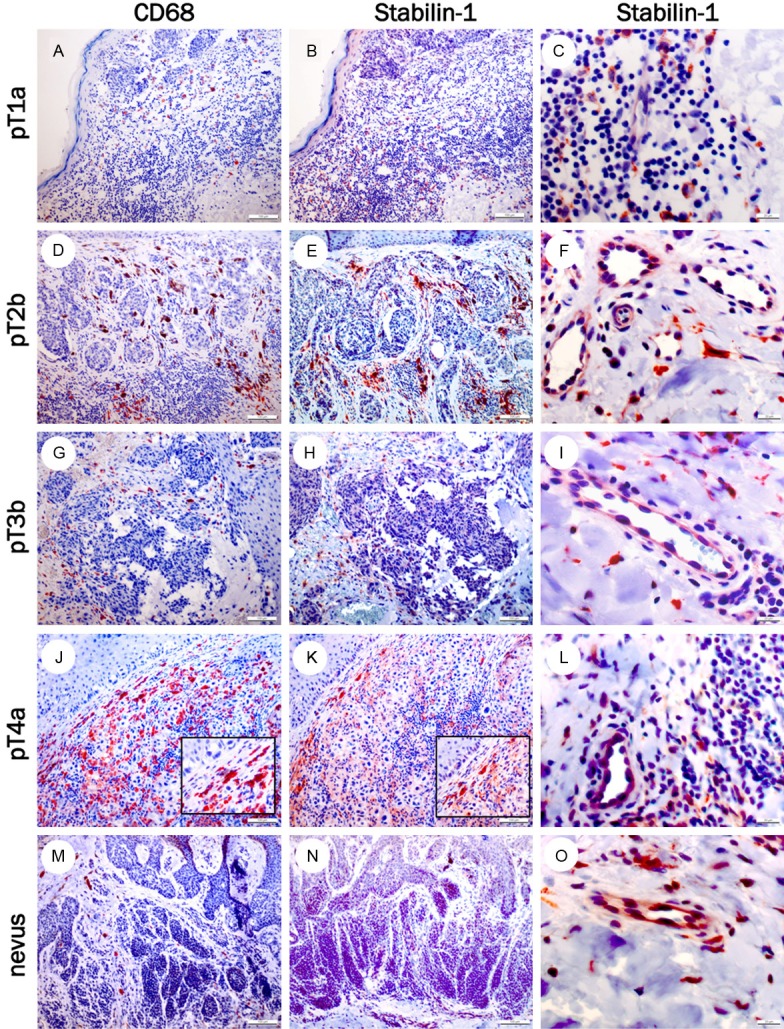

Stabilin-1 expression has been described in tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) in murine melanomas, breast carcinomas [15] and glioblastomas [12,16]. To verify the presence of stabilin-1+ macrophages in human melanomas, at least three different melanomas of each pathological stage were stained with pan macrophage marker CD68 (Figure 1A, 1D, 1G, 1J) and the RS1 antibody (Figure 1B, 1C, 1E, 1F, 1H, 1I, 1K, 1L, Table 1). Stabilin-1+ macrophages were found in all pathological stages of melanoma (Figure 1B, 1E, 1H, 1K, Table 1). In our patient cohort, no obvious correlation between stabilin-1+ TAM infiltration in melanomas with positive/negative sentinel lymph nodes or TNM classification was detected (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Stabilin-1 expression in melanocytic lesions. CD68+ (left panel), stabilin-1+ macrophages (middle panel) and stabilin-1+ vessels (right panel) in melanoma specimens of pT1a (A-C), pT2b (D-F), pT3b (G-I), pT4a (J-L) and in a human nevus (M-O) at a magnification of 100x for left and middle panel and 400x for right panel.

To verify whether stabilin-1+ macrophages can also be found in benign lesions, six melanocytic nevi were stained with the RS1 antibody. Stabilin-1+ expression in nevus-associated macrophages was found in nearly all lesions, indicating that the presence of stabilin-1+ macrophages is not indicative of a melanoma (Figure 1M-O).

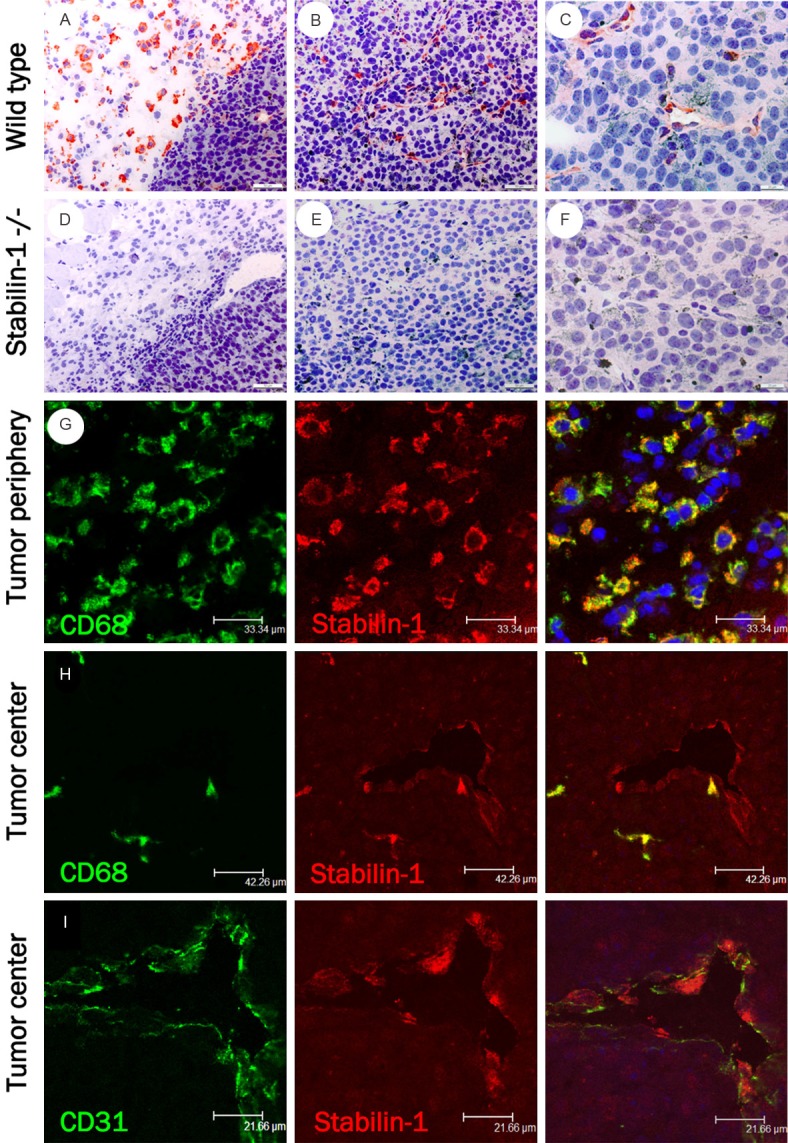

During the histopathological analysis, stabilin-1+ vessels in melanocytic nevi, as well as in melanomas were identified (Figure 1C, 1F, 1I, 1L, 1O, Tables 1 and 2). To independently confirm the specificity of the polyclonal RS1 antibody, regarding stabilin-1 expression in endothelial cells, a model of subcutaneously transplanted murine B16F10 melanoma was analysed in wild type C57BL/6 mice and C57BL/6 stabilin-1 knockout mice. There was a strong infiltration of stabilin-1+ macrophages in the tumor’s periphery of murine melanomas (Figure 2A, 2G), while almost no stabilin-1+ macrophages were observed in the melanoma center (Figure 2B, 2H). Interestingly, many intratumoral vessels showed a strong stabilin-1 expression (Figure 2B, 2C, 2H, 2I). No stabilin-1+ cells, neither macrophages nor endothelial cells were detected in B16F10 melanomas of C57BL/6 stabilin-1 knockout mice (Figure 2D, 2E, 2F), which confirms the specificity of the RS1 antibody for stabilin-1.

Figure 2.

Stabilin-1 expression in murine B16F10. Stabilin-1+ murine macrophages at the (A) periphery of B16F10 melanoma (200x) and stabilin-1+ endothelial-like cells (B, C) in the center of B16F10 melanoma grown subcutaneously in C57BL/6 wild type mice at a magnification of 200x (B) and 400x (C). Stabilin-1 staining of B16F10 melanoma grown in stabilin-1 knockout mice at (D) the tumor periphery (200x) and (E, F) the tumor center. Double immunofluorescent staining (G) with CD68 (green) and stabilin-1 (red) indicate an overlapping pattern (yellow) of CD68+/stabilin-1+ cells in the periphery of B16F10 grown in wild type mice. In the tumor center stabilin-1+ cells (red) overlap either with (H) CD68+ macrophages (green) or (I) CD31+ endothelial cells (green). Original magnification 630x.

After verification of the specificity of RS1 antibody for vessel staining, the presence of stabilin-1+ vessels in human melanocytic nevi and melanomas was analysed. No correlation between stabilin-1+ vessels with pathological melanoma stages (pT1-pT4) was noticed (Table 1). Nevertheless, up to 40% stabilin-1+ vessels were also found in melanocytic nevi.

Stabilin-1 expression in non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses and other granulomatous disease

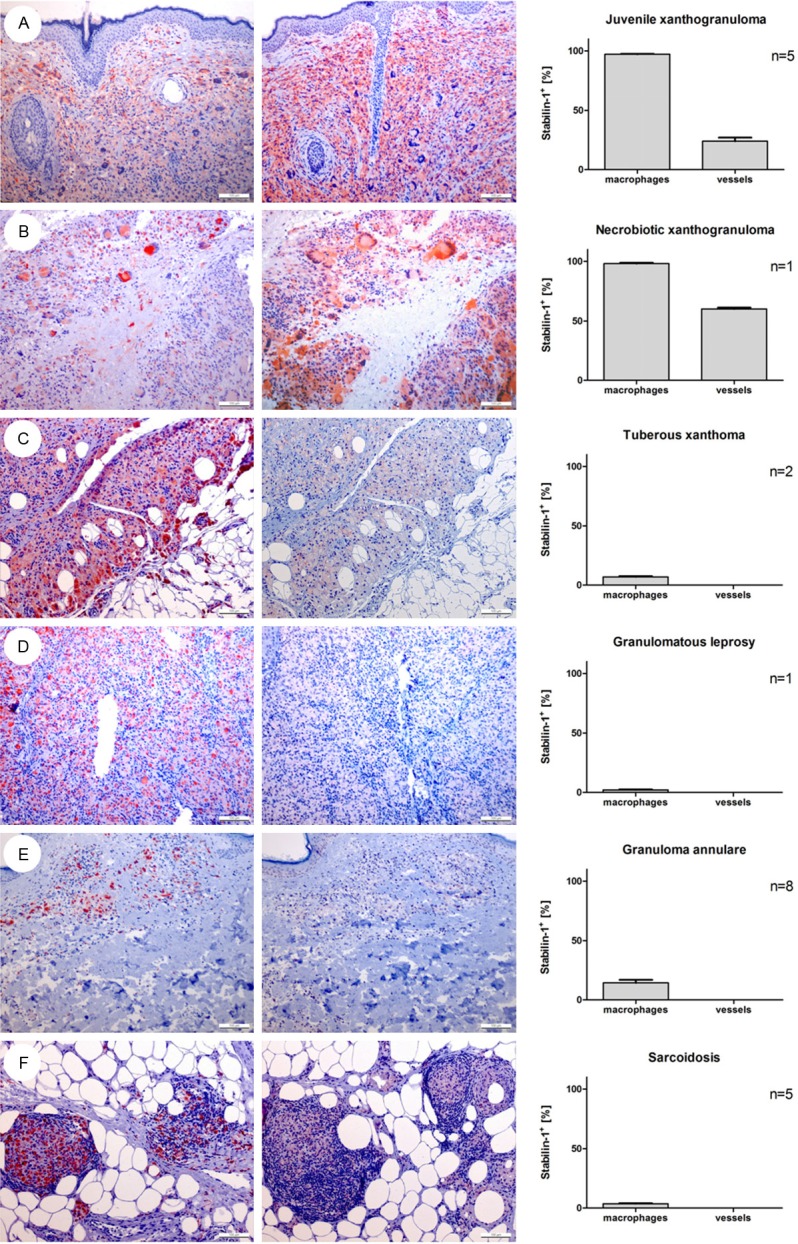

It has already been described by Goerdt et al. [3], that juvenile xanthogranulomas, which belong to the non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses, are strongly stabilin-1 positive. To confirm stabilin-1 expression in juvenile xanthogranulomas with the RS1 antibody in paraffinembedded tissue, five cases of juvenile xanthogranulomas were stained. In addition, one case of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma was added to the study (Figure 3A, 3B). Stabilin-1 expression was found in juvenile xanthogranulomas as well as in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (Figure 3A, 3B). In addition, high percentages of stabilin-1+ vessels (between 12.7% and 60.0%) were noticed. On the other hand, tuberous xanthomas stained negative (Figure 3C) [3].

Figure 3.

Stabilin-1 expression in human granulomatous diseases. Exemplary CD68+ (left panel) and stabilin-1+ stainings (middle panel) and corresponding percentage of stabilin-1+ macrophages in relation to CD68+ macrophages and percentage of stabilin-1+ vessels (right panel) in specimens of (A) juvenile xanthogranuloma, (B) necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, (C) tuberous xanthoma, (D) granulomatous leprosy, (E) granuloma annulare and (F) sarcoidosis are shown at an original magnification of 100x.

No significant stabilin-1 expression was found in Th1 cytokine dominated granulomatous disease as granulomatous leprosy, granuloma annulare and sarcoidosis (Figure 3D-F). In addition, not only was the macrophage staining with the RS1 antibody negative in these lesions, there was also no noticed stabilin-1 expression in the surrounding vessels either (Figure 3D-F).

Discussion

Macrophages are phagocytic cells important for a plethora of diverse functions in the body. Broadly, they are divided into pro-inflammatory or M1-like macrophages, which are held against anti-inflammatory or M2-like macrophages. In vitro, M1 macrophages are induced by IFN-γ or TNF-α, while M2 macrophages result from stimulation with IL-10, glucocorticoids, IL-4 and IL-13 [17]. In vivo, M2-like macrophages are important for tissue regeneration, immunosuppression and clearance of cell debris [18]. Their presence in neoplastic tissue has therefore been associated with a worse prognosis for patients [19]. While identification of M2 macrophages in mice is possible on the basis of well-defined M2-marker profiles; in humans, no highly specific M2-marker profile has been established so far [19]. One of the most frequently used M2 markers in human tumors is CD163. Although CD163 is expressed by a macrophage subpopulation, an association of CD163 expression with M2 macrophage differentiation remains controversially discussed as in vitro, this marker molecule is induced in monocytes/macrophages not only by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, but also by pro-inflammatory toll-like receptor agonists and IL-6 [20]. Stabilin-1, on the other hand, is specifically up-regulated by IL-4/glucocorticoid stimulation in peripheral blood monocytes.

As in murine subcutaneous implanted melanomas, stabilin-1+ TAM have been described [12], we systematically stained diverse human pathological stages of melanoma and six cases of melanocytic nevi for the presence of stabilin-1+ cells. Results showed a strong infiltration of stabilin-1+ TAM in nearly all pathological stages of melanoma, but stabilin-1+ macrophages were also found in melanocytic nevi; which ruled out stabilin-1 as a useful marker to distinguish malignant from benign melanocytic lesions. Recently, in human colorectal carcinomas, a high number of peritumoral stabilin-1+ macrophages correlated positively with survival [21]. However, in advanced stage IV colorectal cancer patients, a higher number of stabilin-1+ TAM in the tumor stroma and tumor periphery correlated with a shorter disease free survival [21]. Therefore, the role of stabilin-1 for the tumor development and progression requires further clarification. In our work focusing on melanocytic lesions, the analysed number of patients was too small to come to any conclusions regarding stabilin-1 expression and disease outcome, but our data did not show any drastic differences regarding positive/negative sentinel lymph nodes or clinical stage at the first presentation.

Independent of macrophages, stabilin-1 expression was also identified in vessels in human melanomas and nevi, as well as in all juvenile and necrobiotic xanthogranulomas. Specificity of RS1 dependent Stabilin-1 vessel staining was confirmed in a murine tumor model including a Stabilin-1 deficient mouse. Here, RS1 antibody stained nearly all vessels in the B16F10 tumor stroma of wild type mice; while no stabilin-1+ vessels were detected in the tumor stroma of stabilin-1 knockout mice. Independently, Stabilin-1+ vessels have already been described by Goerdt et al. [22] in human melanocytic nevi, primary melanomas, melanoma metastasis and in histiocytic and vascular lesions with the Stabilin-1 specific MS-1 antibody in frozen sections.

In human diseases, juvenile xanthogranulomas and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, were characterized by the stabilin-1+ infiltrating cells, while tuberous xanthomas remained stabilin-1 negative. Juvenile xanthogranulomas are mostly seen in children as solitary or multiple lesions seldom presenting as systemic diseases; necrobiotic xanthogranulomas appear in the elderly and are frequently associated with monoclonal gammopathies [23]. Both disease entities are regarded as reactive disease, but while juvenile xanthogranulomas are regarded as part of non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses, the classification of necrobiotic xanthogranulomas is still a matter of debate. Histopathologically, juvenile and necrobiotic xanthogranulomas show many similarities, such as the presence of histiocytes in combination with intermingled Touton-type giant cells and the positive staining for stabilin-1. However, while the former is a xanthogranulomatous tissue response, the latter presents as a palisading granuloma with relation to granuloma anulare and necrobiosis lipoidica. Further studies are needed to address the question, whether necrobiotic xanthogranuloma should be sub-classified as non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Other localised and systemic non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses have been described in the literature as adult type xanthogranulomas [24,25], benign cephalic histiocytosis [26], xanthoma disseminatum [27], generalised eruptive histiocytoma [28], papular xanthoma [28], progressive nodular histiocytosis [29] or spindle cell xanthogranuloma [30]. As these non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis are extremely rare, we were not able to include them in this study. Nevertheless, a systematic analysis of all forms of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Langerhans cell histiocytosis with the stabilin-1 antibody would be of interest, as a differential expression might help in distinguishing forms with a benign from those with a progressive clinical course.

Taken together, stabilin-1 detects M2 macrophages in human melanomas as well as in melanocytic nevi, but nearly no stabilin-1 positivity was detected in typical Th-1 cytokine dominated granulomatous diseases such as granulomatous leprosy, granuloma annulare or sarcoidosis. In addition, stabilin-1 is a useful marker to identify juvenile xanthogranulomas and necrobiotic xanthogranulomas.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB938, project H to S.G. and by the Olympia Morata Stipendium to A.S.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Goerdt S, Walsh LJ, Murphy GF, Pober JS. Identification of a novel high molecular weight protein preferentially expressed by sinusoidal endothelial cells in normal human tissues. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1425–1437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goerdt S, Orfanos CE. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goerdt S, Kolde G, Bonsmann G, Hamann K, Czarnetzki B, Andreesen R, Luger T, Sorg C. Immunohistochemical comparison of cutaneous histiocytoses and related skin disorders: diagnostic and histogenetic relevance of MS-1 high molecular weight protein expression. J Pathol. 1993;170:421–427. doi: 10.1002/path.1711700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Schmuttermaier C, Brundiers H, Krusell L, Mamidi S, Zhang J, Workman G, Sage EH, Anderle C, Sedlmayr P, Goerdt S. Alternatively activated macrophages regulate extracellular levels of the hormone placental lactogen via receptor-mediated uptake and transcytosis. J Immunol. 2008;180:3028–3037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kzhyshkowska J, Workman G, Cardo-Vila M, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Gratchev A, Krusell L, Goerdt S, Sage EH. Novel function of alternatively activated macrophages: stabilin-1-mediated clearance of SPARC. J Immunol. 2006;176:5825–5832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R, Oteiza A, Sorensen KK, McCourt P, Olsen R, Smedsrod B, Svistounov D. Role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and stabilins in elimination of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G71–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00215.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pempe EH, Xu Y, Gopalakrishnan S, Liu J, Harris EN. Probing structural selectivity of synthetic heparin binding to Stabilin protein receptors. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20774–20783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kzhyshkowska J. Multifunctional receptor stabilin-1 in homeostasis and disease. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:2039–2053. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schledzewski K, Geraud C, Arnold B, Wang S, Grone HJ, Kempf T, Wollert KC, Straub BK, Schirmacher P, Demory A, Schonhaber H, Gratchev A, Dietz L, Thierse HJ, Kzhyshkowska J, Goerdt S. Deficiency of liver sinusoidal scavenger receptors stabilin-1 and -2 in mice causes glomerulofibrotic nephropathy via impaired hepatic clearance of noxious blood factors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:703–714. doi: 10.1172/JCI44740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Politz O, Gratchev A, McCourt PA, Schledzewski K, Guillot P, Johansson S, Svineng G, Franke P, Kannicht C, Kzhyshkowska J, Longati P, Velten FW, Johansson S, Goerdt S. Stabilin- 1 and -2 constitute a novel family of fasciclin-like hyaluronan receptor homologues. Biochem J. 2002;362:155–164. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martens JH, Kzhyshkowska J, Falkowski-Hansen M, Schledzewski K, Gratchev A, Mansmann U, Schmuttermaier C, Dippel E, Koenen W, Riedel F, Sankala M, Tryggvason K, Kobzik L, Moldenhauer G, Arnold B, Goerdt S. Differential expression of a gene signature for scavenger/lectin receptors by endothelial cells and macrophages in human lymph node sinuses, the primary sites of regional metastasis. J Pathol. 2006;208:574–589. doi: 10.1002/path.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schledzewski K, Falkowski M, Moldenhauer G, Metharom P, Kzhyshkowska J, Ganss R, Demory A, Falkowska-Hansen B, Kurzen H, Ugurel S, Geginat G, Arnold B, Goerdt S. Lymphatic endothelium-specific hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1 is expressed by stabilin-1+, F4/80+, CD11b+ macrophages in malignant tumours and wound healing tissue in vivo and in bone marrow cultures in vitro: implications for the assessment of lymphangiogenesis. J Pathol. 2006;209:67–77. doi: 10.1002/path.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Algars A, Irjala H, Vaittinen S, Huhtinen H, Sundstrom J, Salmi M, Ristamaki R, Jalkanen S. Type and location of tumor-infiltrating macrophages and lymphatic vessels predict survival of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:864–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palani S, Maksimow M, Miiluniemi M, Auvinen K, Jalkanen S, Salmi M. Stabilin-1/CLEVER-1, a type 2 macrophage marker, is an adhesion and scavenging molecule on human placental macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2052–63. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmieder A, Schledzewski K, Michel J, Schonhaar K, Morias Y, Bosschaerts T, Van den Bossche J, Dorny P, Sauer A, Sticht C, Geraud C, Waibler Z, Beschin A, Goerdt S. The CD20 homolog Ms4a8a integrates pro- and anti-inflammatory signals in novel M2-like macrophages and is expressed in parasite infection. Eur J Immunol. 2010;42:2971–2982. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David C, Nance JP, Hubbard J, Hsu M, Binder D, Wilson EH. Stabilin-1 expression in tumor associated macrophages. Brain Res. 2012;1481:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver LK, Pioli PA, Wardwell K, Vogel SN, Guyre PM. Up-regulation of human monocyte CD163 upon activation of cell-surface Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:663–671. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Algars A, Irjala H, Vaittinen S, Huhtinen H, Sundstrom J, Salmi M, Ristamaki R, Jalkanen S. Type and location of tumor-infiltrating macrophages and lymphatic vessels predict survival of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:864–873. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goerdt S, Sorg C. Endothelial heterogeneity and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: a paradigm for the pathogenesis of vascular disorders. Clin Investig. 1992;70:89–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00227347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura F, Yamashita S, Hirano K, Ishigami M, Hiraoka H, Tamura R, Nakagawa T, Nishida M, Sakai N, Nakamura T, Nozaki S, Funahashi T, Matsumoto C, Higashiyama M, Yoshikawa K, Matsuzawa Y. Activation of monocytes in vivo causes intracellular accumulation of lipoprotein-derived lipids and marked hypocholesterolemia--a possible pathogenesis of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Atherosclerosis. 1999;142:355–365. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adamson H. Society intelligence: The Dermatological Society of London. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gartmann H, Tritsch H. [Nevoxanthoendothelioma with small and large nodules. Report on 13 cases] . Arch Klin Exp Dermatol. 1963;215:409–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. [Singular “infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles”] . Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:232–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery HOA. Xanthomatosis: correlation of clinical, histopathologic and chemical studies of cutaneous xanthoma. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1938;37:373–402. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkelmann RK. Cutaneous syndromes of non-X histiocytosis. A review of the macrophage-histiocyte diseases of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taunton OD, Yeshurun D, Jarratt M. Progressive nodular histiocytoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1505–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zelger BG, Zelger B, Steiner H, Mikuz G. Solitary giant xanthogranuloma and benign cephalic histiocytosis--variants of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]