Abstract

Endometrial polyp is a common benign lesion that protrudes into the endometrial surface. The incidence of carcinoma within endometrial polyp is thought to be low, however, postmenopausal women with endometrial polyps are at an increased risk. Endometrial clear cell adenocarcinoma is a distinct and relatively rare subtype of endometrial carcinoma, and recent studies have proposed putative precursor lesions of clear cell adenocarcinoma, namely clear cell endometrial glandular dysplasia (EmGD) and clear cell endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (EIC). Herein, we describe two cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma present exclusively within endometrial polyp and discuss the association of its precursor. Two postmenopausal Japanese females, 66-year-old (Case 1) and 54-year-old (Case 2) presented with abnormal genital bleeding. Cytological examination of both cases revealed adenocarcinoma, thus, hysterectomy was performed. Histopathological studies demonstrated clear cell adenocarcinoma within exclusively endometrial polyp in both cases. The peculiar finding in Case 1 was presence of atypical glandular cells with large round to oval nuclei and clear cytoplasm within the atrophic endometrial glands in the surrounding endometrial tissue, which corresponded to clear cell EIC. A recent study showed that 33% of uteri had at least one focus of clear cell EmGD in endometrial polyps. Accordingly, clear cell adenocarcinoma and clear cell EmGD can occur in association with endometrial polyps more frequently than previously thought. Therefore, detailed histopathological examination is important in diagnosis of endometrial polyps, especially in the postmenopausal women, moreover cytological examination is a useful tool in the postmenopausal women with endometrial polyps.

Keywords: Clear cell adenocarcinoma, endometrial polyp, precursors, endometrial glandular dysplasia

Introduction

Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the endometrium is a distinct histopathological subtype of endometrial carcinoma and is classified as type II carcinoma of the endometrium [1]. The incidence of this type of carcinoma is less common (1-5% of all endometrial carcinomas), and occurs in older patients like serous adenocarcinoma [1].

Endometrial polyp is a relatively common benign lesion that protrudes above the endometrial surface, and consists of endometrial glands and stroma that is typically at least focally fibrous and contains thick-walled vessels [1]. The incidence of carcinoma within endometrial polyp is thought to be low, however, postmenopausal women with endometrial polyp are at an increased risk of malignancy, as compared to premenopausal women [2-4]. It has been reported that 10-34% of endometrial carcinomas in postmenopausal women are associated with endometrial polyps [2]. The most common histopathological subtype of endometrial carcinoma associated with endometrial polyp is endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and the less common subtype is serous adenocarcinoma [2]. Clear cell adenocarcinoma associated with endometrial polyp has been rarely reported [6,7]. Herein, we describe two cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma present exclusively within endometrial polyp and discuss the relationship between clear cell adenocarcinoma and its putative precursor.

Case report

Case 1

A 66-year-old postmenopausal Japanese female presented with abnormal genital bleeding.Ultrasound examination revealed a polypoid lesion in the fundus of the uterine corpus. Biopsy and cytological examinations of the endometrium were performed. The biopsy specimen contained no endometrial tissue; however, the cytological specimen demonstrated adenocarcinoma. Subsequently, another biopsy from the endometrium was performed, which revealed clear cell adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Thus, she underwent total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with lymph node dissection.

Histopathological study of the surgically resected specimen of the uterus showed a polypoid lesion protruding into the endometrial surface in the fundus of the uterine corpus. The polypoid lesion was composed of fibrous stroma, thick-walled vessels and atrophic endometrial glands (Figure 1A). Most of the endometrial glands were dilated and had small nuclei with small nucleoli. No mitotic figures were found in these atrophic endometrial glands. These features are typical for endometrial polyp. There was a small infiltrative neoplastic growth restricted to the top of the endometrial polyp (Figure 1A, arrow). The infiltrative neoplastic growth was comprised of solid and tubulocystic patterns (Figure 1B). The neoplastic cells had clear cytoplasm and large round to oval nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli, and hobnail-appearing tumor cells were also observed (Figure 1B). Mitotic figures were frequently seen (7/5 high power fields). These histopathological features are typical for clear cell adenocarcinoma. No lymph node metastasis was noted.

Figure 1.

Histopathological features of Case 1. A. A polypoid lesion composed of dilated endometrial glands, fibrous stroma and thick-wall vessels is present in the endometrium. On top of the polyp, infiltrative solid and tubulocystic growth is observed (arrows), HE. x 40. B. The neoplastic cells have large round to oval nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and clear cytoplasm, HE. x 200. C. In the surrounding endometrium, a few atypical cells with large round to oval nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and clear cytoplasm are present within the atrophic endometrial gland (arrow), which correspond to clear cell endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma, HE. x 400.

The surrounding endometrial tissue was atrophic, however, only a few atrophic glands containing large atypical cells were observed without continuity with the endometrial polyp (Figure 1C, arrow). These atypical cells had large round to oval nuclei (the nuclear size was more than 3-fold bigger than that of the atrophic endometrial glandular cells) and relatively rich clear cytoplasm, which resembled the tumor cells of clear cell adenocarcinoma (Figure 1C, arrow). No invasive growth was noted in this lesion.

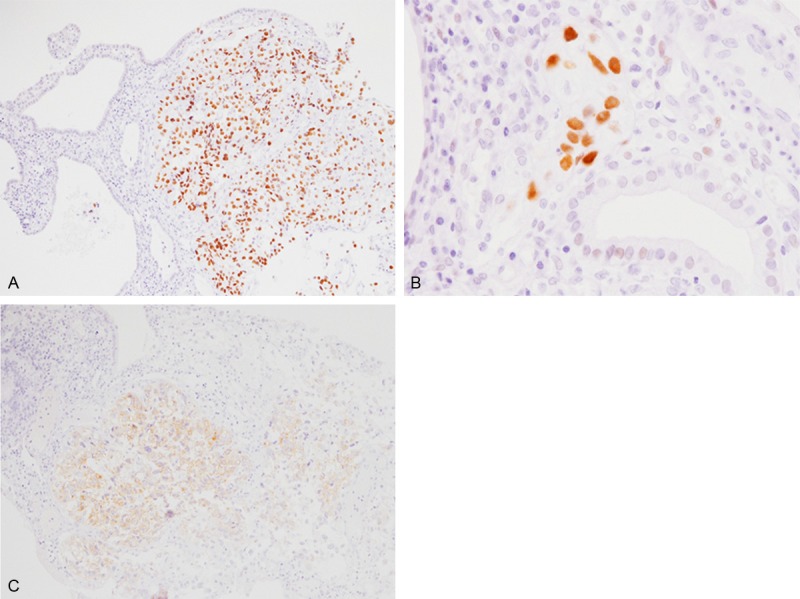

Immunohistochemical studies were performed using an autostainer (Ventana) by the same method as previously reported [8-12]. p53 protein was diffusely expressed in the clear cell adenocarcinoma (Figure 2A) and the atypical glands within the atrophic endometrial glands (Figure 2B). However, the atrophic endometrial glands were negative for p53 protein. IMP3 was also expressed in the clear cell adenocarcinoma (Figure 2C) and the atypical glands within the atrophic endometrial glands, but not in the atrophic endometrial glands. On the other hand, estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PgR) were expressed in the atrophic endometrial glands, but not in the clear cell adenocarcinoma and atypical glands within the atrophic endometrial glands.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical findings of Case 1. A. p53 protein is diffusely expressed in the clear cell adenocarcinoma, but not in the endometrial polyp, x 200. B. p53 protein is also expressed in the clear cell endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma, x 400. C. IMP3 is diffusely expressed in the clear cell adenocarcinoma, x 200.

Accordingly, an ultimate diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma restricted within an endometrial polyp (stage IA, pT1aN0M0) was made.

Case 2

A 54-year-old postmenopausal Japanese female presented with abnormal genital bleeding, and the endometrial cytological examination at an outpatient clinic revealed adenocarcinoma. Ultrasound examination revealed a polypoid lesion in the fundus of the uterine corpus, and the biopsy from the polypoid lesion demonstrated clear cell adenocarcinoma. Subsequently, total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed.

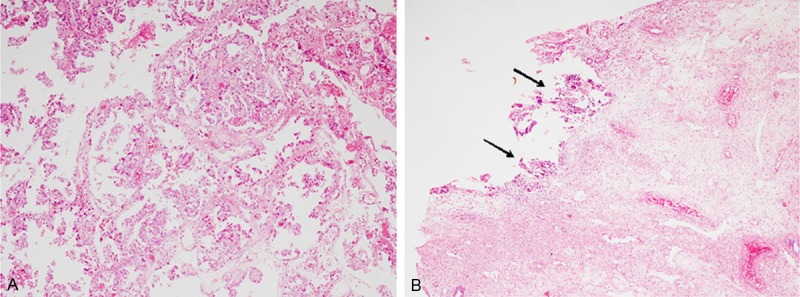

Histopathological analyses of the biopsy specimen demonstrated papillary and tubulocystic proliferation of atypical cells with large round to oval nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and clear cytoplasm (Figure 3A). Tumor cells showing hobnail features were also observed. These features are typical for clear cell adenocarcinoma. The surgically resected specimen revealed an endometrial polyp in the fundus of the uterine corpus. The endometrial polyp was composed of fibrous stroma and thick-walled vessels, and atrophic endometrial glands were also present. Only a small focus of residual clear cell adenocarcinoma was present on the top of the endometrial polyp (Figure 3B, arrows).

Figure 3.

Histopathological features of Case 2. A. Biopsy specimen reveals papillary and tubulocystic growth of neoplastic cells with large round to oval nuclei and clear cytoplasm, HE. x 100. B. A surgically resected specimen contains small focus of the residual clear cell adenocarcinoma on top of the endometrial polyp (arrows), HE, x 40.

The surrounding endometrial tissue contained atrophic endometrial glands. No atypical glands were observed in the surrounding endometrial tissue.

Immunohistochemical study revealed that clear cell adenocarcinoma was positive for p53 protein and IMP3, but negative for ER and PgR. In contrast, the atrophic endometrial glands were negative for p53 protein and IMP3, but positive for ER and PgR.

Accordingly, an ultimate diagnosis of clear cell adenocarcinoma restricted within an endometrial polyp (stage IA, pT1aN0M0) was made.

Discussion

Endometrial carcinoma is divided into two subtypes; namely, type I (endometrioid adenocarcinoma) and type II (serous and clear cell adenocarcinomas). They have different clinicopathological features and genetic background. For example, type I carcinoma frequently harbors PTEN inactivation or beta-catenin mutation, and in contrast, type II carcinoma often has TP53 mutation [1]. It has been well recognized that endometrial hyperplasia may be a precursor lesion of endometrioid adenocarcinoma [1]. Recent studies also suggested that endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (EIC) is a putative precursor of serous adenocarcinoma, which is referred to as serous adenocarcinoma in situ [13,14]. Serous adenocarcinoma and/or EIC arising within endometrial polyps have been reported [5,15-18].

It is well known that endometrial polyps are associated with the occurrence of endometrial carcinomas. Martin-Ondarza et al. analyzed 1,492 cases of endometrial polyps [2], who were predominantly postmenopausal women, and found twenty-seven cases of carcinoma in endometrial polyps, which accounted for 1.8% of endometrial polyp and 13.2% of endometrial carcinoma [2]. The most common histopathological subtype was endometrioid adenocarcinoma (81.5%) followed by serous adenocarcinoma (19.5%), but clear cell adenocarcinoma was not present in their series [2]. They recommended that postmenopausal women with endometrial polyps should undergo direct biopsies [2]. Recently, Yasuda et al. reported 8 cases of EIC in association with endometrial polyps [5]. In their series, all patients were postmenopausal, and three of 8 cases showed minimal stromal invasion restricted to the endometrial polyps [5]. The interesting finding of their report was that tumor cells resembling EIC within the endometrial polyps were also observed in the surrounding atrophic endometrial glands in 4 cases [5]. Moreover, they emphasized that endometrial cytological examination revealed adenocarcinoma in all 8 cases although the endometrial biopsy detected adenocarcinoma in only 2 cases [5]. In the present report, endometrial cytological examination demonstrated adenocarcinoma in both cases although the endometrial biopsy failed to detect adenocarcinoma in Case 1. Therefore, endometrial cytological examination is a useful diagnostic tool in postmenopausal patients with endometrial polyps because the biopsy may sometimes fail to detect tiny adenocarcinoma within endometrial polyps.

Recently, the concept of “endometrial glandular dysplasia (EmGD)” has been proposed [20-22]. EmGD is defined as single glands or small glandular groups within the superficial endometrium or a flat layer of epithelium on the endometrium, composing of a lining of cells with nucleomegaly (2-4 times the size of nuclei in resting endometrium and 4-5 times of those in serous EIC), variably conspicuous nucleoli, variable hyperchromasia, and loss of nuclear polarity [20,22]. Zheng et al. demonstrated that EmGD was present in 53% of the surrounding endometrial tissues of serous adenocarcinoma cases and 1.7% of endometrioid adenocarcinoma cases [20]. Therefore, they concluded that EmGD represents the true precursor of endometrial serous adenocarcinoma and endometrial serous carcinogenesis is also a morphologically identifiable stepwise process rather than de novo derivation from resting endometrium [20,22]. Moreover, they provided molecular evidence to support EmGD as the precursor lesion of serous adenocarcinoma. p53 mutations were identified in 0%, 43%, 72%, and 96% of resting endometrium, EmGD, serous EIC, and serous adenocarcinoma, respectively [23], and IMP3, one of the oncofetal protein highly expressed in fetal tissues and some malignant tumors but rarely found in normal adult tissues, was expressed in 14% of EmGD, 89% of EIC, and 94% of serous adenocarcinomas (this protein was also expressed in only 7% of endometrioid adenocarcinomas and 25% of clear cell adenocarcinomas) [24].

Moreover, potential precursor lesions of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the endometrium have also been proposed [25]. In 2004, Moid and Berezowski reported a very interesting lesion in a 70-year-old postmenopausal woman, which they designated as “EIC, clear cell type” [26]. Subsequently, Fadare et al. analyzed the clinicopathological features of the precursors of endometrial clear cell adenocarcinoma [25]. In their series, 90% of clear cell adenocarcinoma had at least one putative precursor lesion in the surrounding endometrium adjacent to the clear cell adenocarcinoma (2.5 foci/case); in contrast, precursor lesions were identified neither in the benign uteri nor in endometrioid adenocarcinoma specimens [25]. These lesions were characterized by the presence of single glands, small glandular clusters or segments of surface endometrium lined by cells that typically display cytoplasmic clarity and/or eosinophilia and a continuous gradation of nuclear atypicality. They graded these lesions based on the severity of the nuclear changes with grade 3 lesions being lined by overtly malignant cells comparable to those of the adjacent malignancies [25]. Grade 3 lesions are identical to clear cell EIC, while grade 1 and 2 lesions are designated as clear cell EmGD [25]. Immunohistochemically, p53 protein expression scores for the benign endometrium, these precursor lesions, and clear cell adenocarcinoma were 0, 4.5, and 6.2, respectively [25]. In the present Case 1, a few atypical glands with large round to oval nuclei and clear cytoplasm were present within the atrophic endometrium (the nuclear size of these atypical cells were the same as those of the clear cell adenocarcinoma). These atypical cells were positive for p53 protein and IMP3, like those of the clear cell adenocarcinoma within the endometrial polyp. Therefore, these atypical glands within the atrophic endometrium are considered as clear cell EIC.

In addition, in the case series of clear cell adenocarcinoma reported by Fadare et al., 33% of uteri showed that at least one focus of clear cell EmGD was located in the endometrial polyps [25]. Moreover, a case of clear cell adenocarcinoma in endometrial polyp associated with clear cell EmGD has also been reported [7]. Accordingly, clear cell adenocarcinoma and its precursor (clear cell EmGD) can occur in association with endometrial polyps more frequently than previously thought. Therefore, detailed histopathological examination is important in diagnosis of endometrial polyps, especially in the postmenopausal women.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Silverberg SG, Kurman RJ, Nogales F, Mutter GL, Kubik-Huch RA, Tavassoli FA. Epithelial tumours and related lesions. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2003. pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin-Ondarza C, Gil-Moreno A, Torres-Cuesta L, Garcia A, Eyzaguirre F, Diaz-Feijoo B, Xercavins J. Endometrial cancer in polyps: A clinical study of 27 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mossa B, Torcia F, Avenoso F, Tucci S, Marziani R. Occurrence of malignancy in endometrial polyps during postmenopause. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2010;31:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrazzi E, Zupi E, Leone FP, Savelli L, Omodei U, Moscarini M, Barbieri M, Cammareri G, Capobianco G, Cicinelli E, Coccia ME, Donarini G, Fiore S, Litta P, Sideri M, Solima E, Spazzini D, Testa AC, Vignali M. How often are endometrial polyps malignant in asymptomatic postmenopausal women? A multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:235e1–235e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda M, Katoh T, Hori S, Suzuki K, Ohno K, Maruyama M, Matsui N, Miyazaki S, Ogane N, Kameda Y. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma in association with polyp: review of eight cases. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadare O, Zheng W, Crispens MA, Jones HW III, Khabele D, Gwin K, Liang SX, Mohammed K, Desouki MM, Parkash V, Hecht JL. Morphologic and other clinicopathologic features of endometrial clear cell carcinoma: a comprehensive analysis of 50 rigorously classified cases. Am J Cancer Res. 2013;3:70–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabrizi AD, Vahedi A, Esmaily HA. Malignant endometrial polyps: Report of two cases and review of literature with emphasis on recent advances. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:574–579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishida M, Iwai M, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Okabe H. Sebaceous carcinoma associated with Bowen’s disease: a case report with emphasis on the pathogenesis of sebaceous carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:3029–3032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toriyama A, Ishida M, Amano T, Nakagawa T, Kaku S, Iwai M, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Takahashi K, Murakami T, Okabe H. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata coexisting with endometriosis within the same lesions: a case report with review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2949–2954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishida M, Hodohara K, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Iwai M, Yoshii M, Okuno K, Horinouchi A, Nakanishi R, Harada A, Yoshida T, Okabe H. Occurence of anaplastic large cell lymphoma following IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis and cholecystitis and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2560–2568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishida M, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Iwai M, Yoshii M, Okuno K, Horinouchi A, Nakanishi R, Harada A, Yoshida T, Okuno T, Hodohara K, Okabe H. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive large B-cell lymphoma: A case report with emphasis on the cytological features of the pleural effusion. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2631–2635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida M, Hodohara K, Yoshii M, Okuno H, Nakanishi R, Horinouchi A, Nakanishi R, Harada A, Iwai M, Yoshida K, Kagotani A, Yoshida T, Okabe H. Methotrexate-related Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder occurring in the gingiva of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2237–2241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambros RA, Sherman ME, Zahn CM, Bitterman P, Kurman RJ. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma: a distinctive lesion specifically associated with tumors displaying serous differentiation. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel GW. Endometrial carcinoma in situ in postmenopausal women. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:417–432. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trahan S, Tetu B, Raymond PE. Serous papillary carcinoma of the endometrium arising from endometrial polyps: a clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1316–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCluggage WG, Sumathi VP, McManus DT. Uterine serous carcinoma and endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma arising in endometrial polyps: report of 5 cases, including 2 associated with tamoxifen therapy. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:939–943. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler DT, Bell KA, Kurman RJ, Sherman ME. Minimal uterine serous carcinoma: diagnosis and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:797–806. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carcangiu ML, Tan LK, Chambers JT. Stage IA uterine serous carcinoma: a study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1507–1514. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199712000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva EG, Jenkins R. Serous carcinoma in endometrial polyps. Mod Pathol. 1990;3:120–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Liang SX, Yu H, Rutherford T, Chambers SK, Schwartz PE. Endometrial glandular dysplasia: a newly defined precursor lesion of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Part I: morphologic features. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:207–223. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang SX, Chambers SK, Cheng L, Zhang S, Zhou Y, Zheng W. Endometrial glandular dysplasia: a putative precursor lesion of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Part II: molecular features. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:319–331. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadare O, Zheng W. Endoemtrial glandular dysplasia (EmGD): morphologically and biologically distinctive putative precursor lesions of type II endometrial cancers. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia L, Liu Y, Yi X, Miron A, Crum CP, Kong B, Zheng W. Endometrial glandular dysplasia with frequent p53 gene mutation: a genetic evidence supporting its precancer nature for endometrial serous carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2263–2269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng W, Yi X, Fadare O, Liang SX, Martel M, Schwartz PE, Jiang Z. The oncofetal protein IMP3: a novel biomarker for endometrial serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:304–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181483ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadare O, Liang SX, Ulukus EC, Chambers SK, Zheng W. Precursors of endometrial clear cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1519–1530. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213296.88778.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moid F, Berezowski K. Pathologic quiz case: a 70-year-old woman with postmenopausal bleeding. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma, clear cell type. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:e157–e158. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-e157-PQCAYW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]