Abstract

Amyloidosis is characterized by an extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils. Amyloid deposition caused various clinical symptoms associated with affected organs. Secondary amyloidosis without renal involvement and chronic inflammatory conditions is rarely reported. We experienced a case of secondary intestinal amyloidosis presented with recurrent hematochezia and abdominal pain in a 54-year-old male. Sigmoidoscopy and abdominal computed tomography (CT) presented ischemic colitis and necrosis of whole colon. On microscopically, pinkish amorphous materials were infiltrated in the lamina propria and the thickened submucosal vessel walls in colon. The apple-green birefringence with polarized light on Congo red stain was demonstrated in the lamina propria and submucosal vessel walls. The deposits were positive for amyloid A and κ and negative for λ. The echocardiography and cardiac MRI findings showed infiltratives cardiomyopathy involving amyloidosis. Despite of conservative treatment, ischemic colitis and hemorrhage were aggravated and the patient expired.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, hematochezia, colon

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a disease characterized by extracelluar deposition of non-branching fibrils. Several forms of amyloidosis has been observed; primary or light chain (L)-associated AL amyloidosis, secondary amyloidosis with acute-phase reactant serum amyloid A protein (AA amyloidosis), familial amyloidosis (ATTR amyloid), hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis (Aβ2 amyloid), senile and localized amylodosis [1-5]. Secondary amyloidosis is associated with infectious, inflammatory, or less commonly, neoplastic disorders and renal dysfunction is the most common symptom of AA amyloidosis at diagnosis [2,6-8]. The clinical manifestation of colonic amyloidosis may similar with other colonic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, collagenous colitis, and malignancy [9,10]. We present an unusual case of intestinal AA amyloidosis with intractable hematochezia, with no renal involvement.

Case report

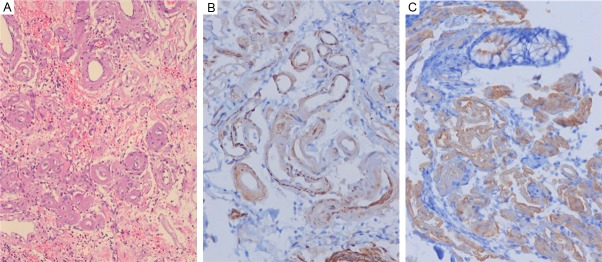

A 54-year-old male was referred to our hospital with a 2 month history of recurrent hematochezia and colicky lower abdominal pain. Two months ago, he visited the other hospital for bloody diarrhea and treated with infectious colitis and symptom was recovered. However, bloody diarrhea was recurred after a month. He was transferred to our hospital for intractable bloody diarrhea and abnormal echocardiography. On admission, he had an average 3 times stool frequency a day, with no abdominal pain, tenesmus, fever, nausea, or vomiting. Physical examination was unremarkable and laboratory findings revealed that red blood cell count 3.77 M/uL (normal range 4.5-6.3); hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL (normal range 14-18); hematocrit, 34.3% (normal range 38-52); white blood cell count 8.87 K/uL (normal range 4-10) with an increasing neutrophil count 66.9% (normal range 55-65%); platelet 262 K/uL (normal range 140-440). Serum IgG 272 mg/dL (normal range 700-1600), IgA 15 mg/dL (normal range 70-400) and IgM 20 mg/dL (normal range 40-230) were all decreased. Other biochemical results were within normal range. Autoantibodies for rheumatic factor, anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were all negative. Toxin A for clostridium difficile was negative in the stool. Stool cultures for Salmonella, Shigella, A. hydrophilia, V. enterocolitica was negative. Simple Abdomen X-ray showed distended small and large bowel by gas with no evidence of obstruction. Colonoscopy showed coarse granular mucosa in whole colon. Especially, diffuse ulceration with necrotic and hemorrhagic materials was observed in sigmoid to descending colon. Multiple biopsies were done through the whole colon. On microscopically, pinkish amorphous materials were infiltrated in the lamina propria and the thickened submucosal vessel walls in colon. The apple-green birefringence with polarized light on Congo red stain was demonstrated in the lamina propria and submucosal vessel walls. The deposits were positive for amyloid A and negative for κ and λ. Echocardiographic examination was performed to evaluate ischemic colitis. The echocardiography revealed asymmetric thickness of septal wall and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse wall thickening of left ventricular, which suggested infiltrative cardiomyopathy involving amyloidosis. Protein electrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis showed negative monoclonal light chains in serum and urine. In spite of conservative treatment, abdominal pain and recurrent hematochezia were continuous and then an elective left hemicolectomy was performed. The several ulcerations with diffuse edematous change were observed in colon. Histologically, pinkish amorphous materials were infiltrated in the thickened submucosal vessels wall in colon (Figure 1A). The apple-green birefringence with polarized light on Congo red stain was demonstrated in the submucosal vessels wall. The deposits were positive for amyloid A (Figure 1B) and κ (Figure 1C) and negative for λ. And ischemic change of mucosa was observed. The patient expired from multiple organ failure on the fifth postoperative day.

Figure 1.

A: Pinkish amorphous materials were infiltrated in the thickened submucosal vessels wall in colon, HE, x200. B: The pinkish amorphous material stains for amyloid A, x200. C: The amyloid stains for κ, x200.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is the extracellular deposition of non-branching fibrils in organs and tissues. Amyloidosis is caused by several different proteins made up the amyloid fibrils [3]. Amyloidosis is classified based on the protein that is present in the amyloid fibrils. Primary amyloidosis (AL Amyloidosis) presented immunoglobulin light chains. AL amyloidosis is the most common form [4]. It is associated with plasma cell dyscrasia related to multiple myeloma and clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow that produce amyloidogenic immunoglobulins [11,12]. Secondary (AA) amyloidosis presented serum amyloid A protein that is associated with infection, inflammatory, or neoplastic disease [1,2]. AA amyloidosis has been reported in inflammatory disorder such as Crohn’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis and serum lupus erythematosus; infectious processes such as tuberculosis, osteomyelitis and leprosy; and neoplastic disorder such as renal cell carcinoma,and gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumors [2,6-8].

The manifestations of amyloidosis were associated with affected organs. Secondary amyloidosis could involve several organs such as kidney, heart and adrenal gland [13]. Renal involvement was the predominant manifestation of secondary amyloidosis [2]. The clinical signs of renal AA amyloidosis presented proteinuria or serum creatinine concentration or both [2]. The clinical sings of renal AA amyloidosis were often missed until the development of nephrotic syndrome [14]. The GI tract is a more common site of amyloid deposition in primary amyloidosis than secondary amyloidosis [15]. The common GI manifestations are non-specific and variable, including erosion, ulceration, bleeding, malabsorption, intractable diarrhea, obstruction, infarction or ischemia [16,17]. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish from other intestinal diseases, such as IBD, ischemic colitis or malignancy [9,10]. Endoscopic and radiologic features are also nonspecific included granular pattern and polypoid protrusions, erosions, ulcerations and mucosal friability [18]. Cardiac involvement is rare in secondary amyloidosis, and even though it detected by echocardiography [19,20]. This patient presented intestinal symptoms at first and abnormality of echocardiography was found incidentally.

The type of amyloidosis must be determined after obtained positive biopsy results. The first step is to search for clonal plasma-cell dyscrasia [21]. Immunofixation electrophoresis of serum or urine used to detect monoclonal immunoglobulins or light chains [21]. Monoclonal immunoglobulins or light chains are detected in most of patients with primary amyloidosis [21]. If there is no evidence of a plasma-cell dyscrasia, another form of amyloidosis should be considered. A familial history of amyloidosis and unexpected progressive neuropathy considered familial ATTR amyloidosis [21].

The aim of therapy for amyloidosis is to slow amyloid formation by reducing production of the amyloidogenic protein and to control of the clinical symptoms [22]. Surgical procedure should be contemplated only in an emergency setting or in localized disease because of the risk of decompensation of organs affected by amyloidosis [9,23]. This patient underwent left hemicolectomy because conservative treatment was not effective and symptoms were aggravated.

Herein, we report a case of secondary intestinal amyloidosis presented with intractable hematochezia. Intestinal amyloidosis should be considered in patients with unresponsive to conventional treatment because its clinical manifestation was variable and non-specific.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 2012 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Secondary Systemic Amyloidosis (AA): Response and Survival in 64 Patients. Medicine. 1991;70:246–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJ, Gilbertson JA, Gallimore JR, Sabin CA, Gallimore JD, Hawkins PN. Natural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2361–2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westermark P, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Cohen AS, Frangione B, Ikeda S, Masters CL, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Sipe JD. Amyloid: Toward terminology clarification report from the nomenclature committee of the international society of amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2005;12:1–4. doi: 10.1080/13506120500032196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebert EC, Nagar M. Gastrointestinal manifestations of amyloidosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:776–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth DR, Tan SY, Booth SE, Tennent GA, Hutchinson WL, Hsuan JJ, Totty NF, Truong O, Soutar AK, Hawkins PN, Bruguera M, Caballeria J, Sole M, Campistol JM, Pepys MB. Hereditary hepatic and systemic amyloidosis caused by a new deletion/insertion mutation in the apolipoprotein AI gene. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2714–2721. doi: 10.1172/JCI118725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennings GH. Amyloidosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J. 1950;1:746–753. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4656.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovat LB, Madhoo S, Pepys MB, Hawkins PN. Long-term survival in systemic amyloid A amyloidosis complicating Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1362–1365. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaakkola H, Törnroth T, Groop PH, Honkanen E. Renal failure and nephrotic syndrome associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST)—a rare cause of AA amyloidosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1517–1518. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.7.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsiouris A, Neale J, Stefanou A, Sziagy EJ. Primary amyloid of the colon mimicking ischemic colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Oct 19; doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02456.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02456.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vernon SE. Amyloid colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:728–730. doi: 10.1007/BF02629550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glenner GG, Terry W, Harada M, Lsersky C, Page D. Amyloid fibril proteins: proof of homology with immunoglobulin light chains by sequence analyses. Science. 1971;172:1150–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3988.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyle RA, Linos A, Beard CM, Linke RP, Gertz MA, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Incidence and natural histroy of primary systemic amyloidosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950 through 1989. Blood. 1992;79:1817–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Röcken C, Shakespeare A. Pathology, diagnosis and pathogenesis of AA amyloidosis. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:111–122. doi: 10.1007/s00428-001-0582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grateau G. Musculoskeletal disorders in secondary amyloidosis and hereditary fevers. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:929–944. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada M, Hatakeyama S, Tsukagoshi H. Gastrointestinal amyloid deposition in AL (primary or myeloma-associated) and AA (secondary) amyloidosis: diagnostic value of gastric biopsy. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:1206–1211. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuang L, Sun W, Gibson MF, Sanusi ID. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis with ulceration, hemorrhage, small bowel diverticula, and perforation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2023–2026. doi: 10.1023/a:1026190809074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tada S, Iida M, Yao T, Kitamoto T, Yao T, Fujishima M. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction in patients with amyloidosis: clinicopathologic differences between chemical types of amyloid protein. Gut. 1993;34:1412–1417. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.10.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tada S, Iida M, Iwashita A, Matsui T, Fuchigami T, Yamamoto T, Yao T, Fujishima M. Endoscopic and biopsy findings of the upper digestive tract in patients with amyloidosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:10–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)70913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubrey SW, Cha K, Simms RW, Skinner M, Falk RH. Electrocardiography and Doppler echocardiography in secondary (AA) amyloidosis. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:313–315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maceira AM, Joshi J, Prasad SK, Moon JC, Perugini E, Harding I, Sheppard MN, Poole-Wilson PA, Hawkins PN, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2005;111:186–193. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000152819.97857.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falk RH, Comenzo RL, Skinner M. The systemic amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:898–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petre S, Shah I, Gilani N. Review article: gastrointestinal amyloidosis–clinical features, diagnosis and therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1006–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sattianayagam PT, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD. Systemic amyloidosis and the gastrointestinal tract. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:608–617. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]