Abstract

Background

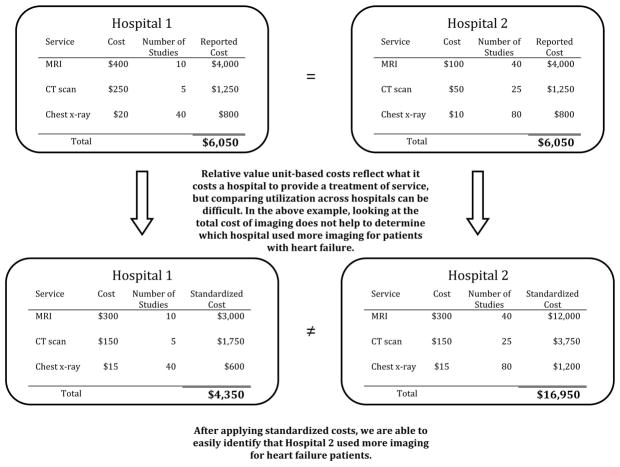

Because Relative Value Unit (RVU)-based costs vary across hospitals, it is difficult to use them to compare hospital utilization.

Objective

To compare estimates of hospital utilization using RVU-based costs and standardized costs.

Design

Retrospective cohort

Setting and Patients

2009–2010 heart failure hospitalizations in a large, detailed hospital billing database that contains an itemized log of costs incurred during hospitalization.

Intervention

We assigned every item in the database with a standardized cost that was consistent for that item across all hospitals.

Measurements

Standardized costs of hospitalization vs. RVU-based costs of hospitalization.

Results

We identified 234 hospitals with 165,647 heart failure hospitalizations. We observed variation in the RVU-based cost for a uniform “basket of goods” (10th percentile cost $1,552; 90th percentile cost of $3,967). The interquartile ratio (Q75/Q25) of the RVU-based costs of a hospitalization was 1.35 but fell to 1.26 after costs were standardized, suggesting that the use of standardized costs can reduce the “noise” due to differences in overhead and other fixed costs. Forty-six (20%) hospitals had reported costs of hospitalizations exceeding standardized costs (indicating that reported costs inflated apparent utilization); 42 hospitals (17%) had reported costs that were less than standardized costs (indicating that reported costs underestimated utilization).

Conclusions

Standardized costs are a novel method for comparing utilization across hospitals and reduce variation observed with RVU-based costs. They have the potential to help hospitals understand how they use resources compared to their peers and will facilitate research comparing the effectiveness of higher and lower utilization.

Keywords: methodology, health sciences research, billing and compliance

INTRODUCTION

Health care spending exceeded $2.5 trillion in 2007, and payments to hospitals represented the largest portion of this spending (more than 30%), equaling the combined cost of physician services and prescription drugs.1,2 Researchers and policymakers have emphasized the need to improve the value of hospital care in the United States, but this has been challenging, in part because of the difficulty in identifying hospitals that have high resource utilization relative to their peers.3–11

Most hospitals calculate their costs using internal accounting systems that determine resource utilization via “Relative Value Units” (RVUs).7,8 RVU-derived costs, also known as “hospital reported costs,” have proven to be an excellent method for quantifying what it costs a given hospital to provide a treatment, test, or procedure. However, RVU-based costs are less useful for comparing resource utilization across hospitals because the cost to provide a treatment or service varies widely across hospitals. The cost of an item calculated using RVUs includes not just the item itself, but also a portion of the fixed costs of the hospital (overhead, labor, and infrastructure investments such as electronic records, new buildings, or expensive radiological or surgical equipment).12 These costs vary by institution, patient population, region of the country, teaching status, and many other variables, making it difficult to identify resource utilization across hospitals.13,14

Recently, a few claims-based multi-institutional datasets have begun incorporating item-level RVU-based costs derived directly from the cost accounting systems of participating institutions.15 Such datasets allow researchers to compare reported costs of care from hospital to hospital, but because of the limitations we described above, they still cannot be used to answer the question: Which hospitals with higher costs of care are actually providing more treatments and services to patients?

In order to better facilitate the comparison of resource utilization patterns across hospitals, we standardized the unit costs of all treatments and services across hospitals by applying a single “cost” to every item across hospitals. This standardized cost allowed us to compare utilization of that item (and the 15,000 other items in the database) across hospitals. We then compared estimates of resource utilization as measured by the two approaches: standardized and RVU-based costs.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

All data were de-identified, by Premier, Inc., at both the hospital and patient level in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The Yale University Human Investigation Committee reviewed the protocol for this study and determined that it is not considered to be Human Subjects Research as defined by the Office of Human Research Protections.

Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from hospitals that participated in the database maintained by Premier Healthcare Informatics, Charlotte, NC, in the years 2009–2010. The Premier database is a voluntary, fee-supported database created to measure quality and health care utilization.3,16–18 In 2010, it included detailed billing data from 500 hospitals in the United States, with more than 130 million cumulative hospital discharges. The detailed billing data includes all elements found in hospital claims derived from the uniform billing 04 (UB-04) form, as well as an itemized, date-stamped log of all items and services charged to the patient or insurer, such as medications, laboratory tests, and diagnostic and therapeutic services. The database includes approximately 15% of all US hospitalizations. Participating hospitals are similar to the composition of acute care hospitals nationwide. They represent all regions of the United States, and represent predominantly small- to mid-sized non-teaching facilities that serve a largely urban population. The database also contains hospital reported costs at the item level as well as the total cost of the hospitalization. Approximately 75% of hospitals that participate submit RVU-based costs taken from internal cost accounting systems. Because of our focus on comparing standardized costs to reported costs, we included only data from hospitals that use RVU-based costs in this study.

Study Subjects

We included adult patients with a hospitalization recorded in the Premier database between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2010 and a principal discharge diagnosis of heart failure (HF) (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 428.xx). We excluded transfers, patients assigned a pediatrician as the attending of record, and those who received a heart transplant or ventricular assist device during their stay. Because cost data are prone to extreme outliers, we excluded hospitalizations that were in the top 0.1% of length of stay, number of billing records, quantity of items billed, or total standardized cost. We also excluded hospitals that admitted fewer than 25 HF patients during the study period in order to reduce the possibility that a single high-cost patient affected the hospital’s cost profile.

Hospital Information

For each hospital included in the study, we recorded number of beds, teaching status, geographic region, and whether it served an urban or rural population.

Assignment of Standardized Costs

We defined reported cost as the RVU-based cost per item in the database. We then calculated the median across hospitals for each item in the database and set this as the “standardized” unit cost of that item at every hospital (Figure 1). Once standardized costs were assigned at the item level, we summed the costs of all items assigned to each patient and calculated the standardized cost of a hospitalization per patient at each hospital.

Figure 1.

Standardized costs allow comparison of utilization across hospitals

Examination of Cost Variation

We compared the standardized and reported costs of hospitalizations using medians, interquartile ranges, and interquartile ratios (Q75/Q25). To examine whether standardized costs can reduce the “noise” due to differences in overhead and other fixed costs, we calculated, for each hospital, the coefficients of variation (CV) for per-day reported and standardized costs and per-hospitalization reported and standardized costs. We used the Fligner-Killeen test to determine whether the variance of CVs was different for reported and standardized costs.19

Creation of “Basket of Goods”

Because there can be differences in the costs of items, the number and types of items administered during hospitalizations, two hospitals with similar reported costs for a hospitalization might deliver different quantities and combinations of treatments (Figure 1). We wished to demonstrate that there is variation in reported costs of items when the quantity and type of item is held constant, so we created a “basket” of items. We chose items that are commonly administered to patients with heart failure, but could have chosen any combination of items. The basket included a day of medical room and board, a day of ICU room and board, a single dose of beta blocker, a single dose of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, complete blood count, a B-natriuretic peptide level, a chest radiograph, a chest CT, and an echocardiogram. We then examined the range of hospitals’ reported costs for this basket of goods using percentiles, medians, and interquartile ranges.

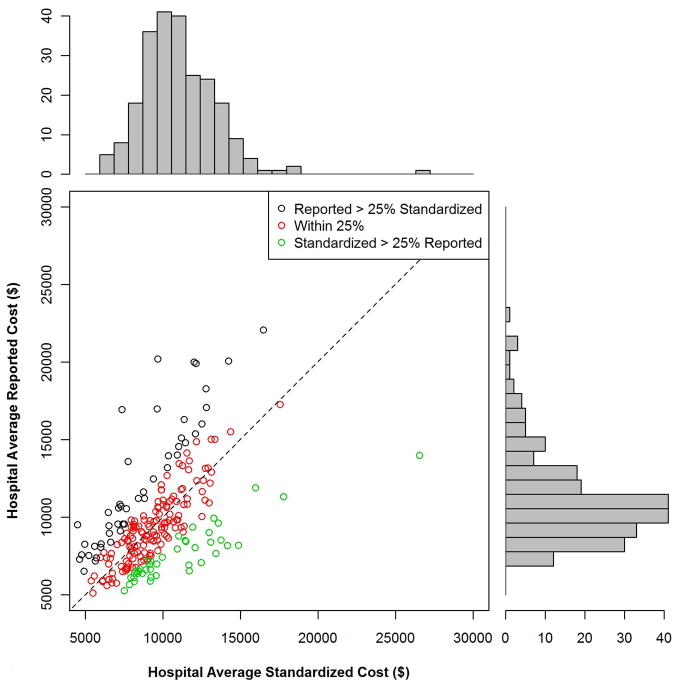

Reported to Standardized Cost Ratio

Next, we calculated standardized costs of hospitalizations for included hospitals and examined the relationship between hospitals’ mean reported costs and mean standardized costs. This ratio could help diagnose the mechanism of high reported costs for a hospital, because high reported costs with low utilization would indicate high fixed costs, while high reported costs with high utilization would indicate greater use of tests and treatments. We assigned hospitals to strata based on reported costs greater than standardized costs by more than 25%; reported costs within 25% of standardized costs; and reported costs less than standardized costs by more than 25%. We examined the association between hospital characteristics and strata using a Chi-square test. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The 234 hospitals included in the analysis contributed a total of 165,647 hospitalizations, with the number of hospitalizations ranging from 33 to 2,772 hospitalizations per hospital (eTable 1). Most were located in urban areas (84%) and many were in the southern United States (42%). The median hospital reported cost per hospitalization was $6,535, with an interquartile range of $5,541 to $7,454. The median standardized cost per hospitalization was $6,602 with a range of $5,866 to $7,386. The interquartile ratio (Q75/Q25) of the reported costs of a hospitalization was 1.35. After costs were standardized, the interquartile ratio fell to 1.26, indicating that variation decreased. We found that the median hospital reported cost per day was $1,651 with an IQR of $1,400 to $1,933 (ratio 1.38) while the median standardized cost per day was $1,640 with an IQR of $1,511 to $1,812 (ratio 1.20).

There were more than 15,000 items (e.g., treatments, tests, and supplies) that received a standardized charge code in our cohort. These were divided into 11 summary departments and 40 standard departments (eTable 2). We observed a high level of variation in the reported costs of individual items: the reported costs of a day of room and board in an ICU ranged from $773 at hospitals at the 10th percentile to $2,471 at the 90th percentile (Table 1a). The standardized cost of a day of ICU room and board was $1,577. We also observed variation in the reported costs of items across item categories. While a day of medical room and board showed a three-fold difference between the 10th and 90th percentile, we observed a more than ten-fold difference in the reported cost of an echocardiogram, from $31 at the 10th percentile to $356 at the 90th percentile. After examining the hospital-level cost for a “basket of goods,” we found variation in the reported costs for these items across hospitals, with a 10th percentile cost of $1,552 and a 90th percentile cost of $3,967.

Table 1.

a) Reported costs of a basket of items commonly used in patients with HF; b) Standardized vs. reported costs of total hospitalizations at 234 hospitals, by hospital characteristics (using all items); c) Characteristics of hospitals with various combinations of reported and standardized costs

| a)

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Costs | 10th Percentile | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 90th Percentile | Median (standardized cost) |

| Item | |||||

| Day of Medical | 490.03 | 586.41 | 889.95 | 1121.2 | 722.59 |

| Day of ICU | 773.01 | 1275.84 | 1994.81 | 2471.75 | 1577.93 |

| Complete Blood Count | 6.87 | 9.34 | 18.34 | 23.46 | 13.07 |

| B-Natriuretic Peptide | 12.13 | 19.22 | 44.19 | 60.56 | 28.23 |

| Metoprolol | 0.2 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 3.74 | 1.66 |

| Lisinopril | 0.28 | 1.02 | 2.79 | 4.06 | 1.72 |

| Spirinolactone | 0.22 | 0.53 | 2.68 | 3.83 | 1.63 |

| Furosemide | 1.267 | 2.45 | 5.73 | 8.12 | 3.82 |

| Chest X-ray | 43.88 | 51.54 | 89.96 | 117.16 | 67.45 |

| Echocardiogram | 31.53 | 98.63 | 244.63 | 356.5 | 159.07 |

| Chest CT (w & w/o Contrast) | 65.17 | 83.99 | 157.23 | 239.27 | 110.76 |

| Non-invasive Positive | 126.23 | 127.25 | 370.44 | 514.67 | 177.24 |

| Pressure Ventilation Electrocardiogram | 12.08 | 18.77 | 42.74 | 64.94 | 29.78 |

| Total “Basket” | 1552.5 | 2157.85 | 3417.34 | 3967.78 | 2710.49 |

| b)

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported >Standardized by >25% n (%) | Reported within 25% (two-tailed) of Standardized n (%) | Reported <Standardized by >25% n (%) | p for Chi-square Test | |

| Total | 46 (19.7) | 146 (62.4) | 42 (17.0) | |

| Number of Beds | 0.2313 | |||

| <200 | 19 (41.3) | 40 (27.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| 200–400 | 14 (30.4) | 67 (45.9) | 15 (35.7) | |

| >400 | 13 (28.3) | 39 (26.7) | 15 (35.7) | |

| Teaching | 0.8278 | |||

| Yes | 13 (28.3) | 45 (30.8) | 11 (26.2) | |

| No | 33 (71.7) | 101 (69.2) | 31 (73.8) | |

| Region | <0.0001 | |||

| Midwest | 7 (15.2) | 43 (29.5) | 19 (45.2) | |

| Northeast | 6 (13.0) | 18 (12.3) | 3 (7.1) | |

| South | 14 (30.4) | 64 (43.8) | 20 (47.6) | |

| West | 19 (41.3) | 21 (14.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Urban (vs. Rural) | 36 (78.3) | 128 (87.7) | 33 (78.6) | 0.1703 |

| c)

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Reported Costs High Standardized Costs |

High Reported Costs Low Standardized Costs |

Low Reported Costs High Standardized Costs |

Low Reported Costs Low Standardized Costs |

|

| Utilization | High | Low | High | Low |

| Severity of illness | Likely to be higher | Likely to be lower | Likely to be higher | Likely to be lower |

| Practice style | Likely to be more intense | Likely to be less intense | Likely to be more intense | Likely to be less intense |

| Fixed costs | High or Average | High | Low | Low |

| Infrastructure costs | Likely to be higher | Likely to be higher | Likely to be lower | Likely to be lower |

| Labor costs | Likely to be higher | Likely to be higher | Likely to be lower | Likely to be lower |

| Reported-to-standardized cost ratio | Close to 1 | >1 | <1 | Close to 1 |

| Causes of high costs | High utilization, high fixed costs, or both | High acquisition costs, high labor costs, or expensive infrastructure | High utilization | - |

| Interventions to reduce costs | Work with clinicians to alter practice style; consider renegotiating cost of acquisitions; hold off on new infrastructure investments | Consider renegotiating cost of acquisitions; hold off on new infrastructure investments; consider reducing size of labor force | Work with clinicians to alter practice style | - |

| Usefulness of reported-to-standardized cost ratio | Less useful | More useful | More useful | Less useful |

We found that 46 (20%) hospitals had reported costs of hospitalizations that were 25% greater than standardized costs (Figure 2). This group of hospitals had reported costs overestimated apparent utilization; 146 (62%) had reported costs within 25% of standardized costs; and 42 (17%) had reported costs that were 25% less than standardized costs (indicating that reported costs underestimated utilization). We examined the relationship between hospital characteristics and strata and found no significant association between the reported to standardized cost ratio and number of beds, teaching status, or urban location (Table 1b). Hospitals in the Midwest and South were more likely to have a lower reported cost of hospitalizations, while hospitals in the West were more likely to have higher reported costs (p<0.001). When using the CV to compare reported costs to standardized costs, we found that per-day standardized costs showed reduced variance (p=0.0238), but there was no significant difference in variance of the reported and standardized costs when examining the entire hospitalization (p=0.1423). At the level of the hospitalization, the Spearman correlation coefficient between reported and standardized cost was 0.89.

Figure 2.

Hospital average reported vs. standardized cost

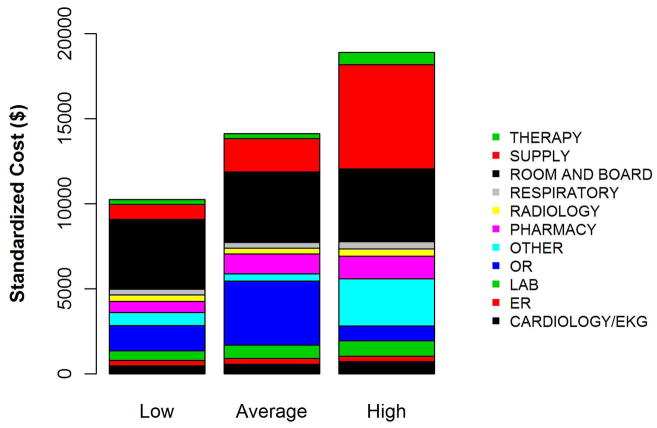

To better understand how hospitals can achieve high reported costs through different mechanisms, we more closely examined three hospitals with similar reported costs (Figure 3). These hospitals represented low, average, and high utilization according to their standardized costs, but had similar average per-hospitalization reported costs: $11,643, $11,787, and $11,892, respectively. The corresponding standardized costs were $8,757, $11,169, and $15,978. The hospital with high utilization ($15,978 in standardized costs) was accounted for by increased use of supplies and “other” services. In contrast, the low- and average-utilization hospitals had proportionally lower standardized costs across categories, with the greatest percentage of spending going towards room and board (which includes nursing).

Figure 3.

Average per-hospitalization standardized cost for three hospitals with reported costs of approximately $12,000

DISCUSSION

In a large national sample of hospitals, we observed variation in the reported costs for a uniform basket of goods, with a more than two-fold difference in cost between the 10th and 90th percentile hospitals. These findings suggest that reported costs have limited ability to reliably describe differences in utilization across hospitals. In contrast, when we applied standardized costs, the variance of per-day costs decreased significantly and the interquartile ratio of per-day and hospitalization costs decreased as well, suggesting less variation in utilization across hospitals than would have been inferred from a comparison of reported costs. Applying a single, standard cost to all items can facilitate comparisons of utilization between hospitals (Figure 1), Standardized costs will give hospitals the potential to compare their utilization to their competitors’ and will facilitate research that examines the comparative effectiveness of high and low utilization in the management of medical and surgical conditions.

The reported to standardized cost ratio is another useful tool. It indicates whether the hospital’s reported costs exaggerate its utilization relative to other hospitals. In this study, we found that a significant proportion of hospitals (20%) had reported costs that exceeded standardized costs by more than 25%. These hospitals have higher infrastructure, labor, or acquisition costs relative to their peers. To the extent that these hospitals might wish to lower the cost of care at their institution, they could focus on renegotiating purchasing or labor contracts, identifying areas where they may be “overstaffed,” or holding off on future infrastructure investments (Table 1c).14 In contrast, 17% of hospitals had reported costs that were 25% less than standardized costs. High-cost hospitals in this group are therefore providing more treatments and testing to patients relative to their peers and could focus cost-control efforts on reducing unnecessary utilization and duplicative testing.20 Our examination of the hospital with high reported costs and very high utilization revealed a high percentage of supplies and “other” items, which is a category used primarily for nursing expenditures (Figure 3). Because the use of nursing services is directly related to days spent in the hospital, this hospital may wish to more closely examine specific strategies for reducing length of stay.

We did not find a consistent association between the reported to standardized cost ratio and hospital characteristics. This is an important finding that contradicts prior work examining associations between hospital characteristics and costs for heart failure patients,21 further indicating the complexity of the relationship between fixed costs and variable costs and the difficulty in adjusting reported costs to calculate utilization. For example, small hospitals may have higher acquisition costs and more supply chain difficulties, but they may also have less technology, lower overhead costs, and fewer specialists to order tests and procedures. Hospital characteristics such as urban location and teaching status are commonly used as adjustors in cost studies because hospitals in urban areas with teaching missions (which often provide care to low income populations) are assumed to have higher fixed costs,3–6 but the lack of a consistent relationship between these characteristics and the standardized cost ratio may indicate that using these factors as adjustors for cost may not be effective and could even obscure differences in utilization between hospitals. Notably, we did find an association between hospital region and the reported to standardized cost ratio, but we hesitate to draw conclusions from this finding because the Premier database is imbalanced in terms of is regional representation, with fewer hospitals in the Midwest and West and a bulk of the hospitals in the South.

Although standardized costs have great potential, this method has limitations as well. Standardized costs can only be applied when detailed billing data with item-level costs are available. This is because calculation of standardized costs requires taking the median of item costs and applying the median cost across the database, maintaining the integrity of the relative cost of items to one another. The relative cost of items is preserved (i.e., an MRI still costs more than an aspirin), which maintains the general scheme of RVU-based costs while removing the “noise” of varying RVU-based costs across hospitals.7 Application of an arbitrary item cost would result in the loss of this relative cost difference. Because item costs are not available in traditional administrative datasets, these datasets would not be amenable to this method. However, highly detailed billing data are now being shared by hundreds of hospitals in the Premier network and the University Health System Consortium. These data are widely available to investigators, meaning that the generalizability of this method will only improve over time. It was also a limitation of the study that we chose a limited “basket” of items common to patients with heart failure in order to describe the range of reported costs and to provide a standardized snapshot by which to compare hospitals. Because we only included a few items, we may have overestimated or underestimated the range of reported costs for such a basket.

Standardized costs are a novel method for comparing utilization across hospitals. Used properly, they will help identify high and low intensity providers of hospital care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by grant DF10-301 from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation in West Hartford, Connecticut; grant UL1 RR024139-06S1 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland; and grant U01 HL105270-02 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Dharmarajan is supported by grant HL007854 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through Columbia University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Donaghue Foundation or the NIH. The funding source had no role in the study’s design, conduct, and reporting.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Krumholz reports that he is the recipient of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc. through Yale University and is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth.

References

- 1.Health Care Costs: A Primer. Kaiser Family Foundation; [Accessed July 20, 2012.]. Available at: http://www.kff.org/insurance/7670.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Squires D. Explaining High Health Care Spending in the United States: An International Comparison of Supply, Utilization, Prices, and Quality. The Commonwealth Fund; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Nathanson BH, Pekow PS, Steingrub JS, Lindenauer PK. The relationship between hospital spending and mortality in patients with sepsis. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):292–299. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skinner J, Chandra A, Goodman D, Fisher ES. The elusive connection between health care spending and quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):w119–123. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasaitis L, Fisher ES, Skinner JS, Chandra A. Hospital Quality And Intensity Of Spending: Is There An Association? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 Jul-Aug;28(4):w566–72. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w566. Epub 2009 May 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Dobson A, Book RA, Epstein AM. Measuring efficiency: the association of hospital costs and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):897–906. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman PA, Hornbrook MC. Assigning resources to health care use for health services research: options and consequences. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S70–75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a75a7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipscomb J, Yabroff KR, Brown ML, Lawrence W, Barnett PG. Health care costing: data, methods, current applications. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S1–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a7e401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett PG. Determination of VA health care costs. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3 Suppl):124S–141S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703256483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett PG. An improved set of standards for finding cost for cost-effectiveness analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S82–88. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819e1f3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Banthin J, et al. Comparison of approaches for estimating prevalence costs of care for cancer patients: what is the impact of data source? Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S64–69. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans DB. Principles involved in costing. Med J Aust. 1990;153 (Suppl):S10–12. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb136982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhardt UE. Spending more through “cost control:” our obsessive quest to gut the hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 1996;15(2):145–154. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.15.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RR, Frutos PW, Ciavarella GG, et al. Distribution of variable vs. fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999;281(7):644–649. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S51–55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c95aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Wang K, Mamidi DK, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Perioperative beta-blocker therapy and mortality after major noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):349–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):486–496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen SI, Dharmarajan K, Kim N, et al. Procedure intensity and the cost of care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(3):308–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conover W, Johnson M, Johnson M. A comparative study of tests for homogeneity of variances, with applications to the outer continental shelf bidding data. Technometrics. 23:351–361. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene RA, Beckman HB, Mahoney T. Beyond the efficiency index: finding a better way to reduce overuse and increase efficiency in physician care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(4):w250–259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.w250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. The association between hospital volume and processes, outcomes, and costs of care for congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):94–102. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.