Abstract

Due to the significantly high levels of comorbid substance use and mental health diagnosis among urban poor populations, examining the intersection of drug policy and place requires a consideration of the role of housing in drug user mental health. In San Francisco, geographic boundedness and progressive health and housing polices have coalesced to make single room occupancy hotels (SROs) a key urban built environment used to house poor populations with co-occurring drug use and mental health issues. Unstably housed women who use illicit drugs have high rates of lifetime and current trauma, which manifests in disproportionately high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression when compared to stably housed women. We report data from a qualitative interview study (n=30) and four years of ethnography conducted with housing policy makers and unstably housed women who use drugs and live in SROs. Women in the study lived in a range of SRO built environments, from publicly-funded, newly built SROs to privately-owned, dilapidated buildings, which presented a rich opportunity for ethnographic comparison. Applying Rhodes et al.’s framework of socio-structural vulnerability, we explore how SROs can operate as “mental health risk environments” in which macro-structural factors (housing policies shaping the built environment) interact with meso-level factors (social relations within SROs) and micro-level, behavioral coping strategies to impact women’s mental health. The degree to which SRO built environments were “trauma-sensitive” at the macro level significantly influenced women’s mental health at meso- and micro- levels. Women who were living in SROs which exacerbated fear and anxiety attempted, with limited success, to deploy strategies on the meso- and micro- level to manage their mental health symptoms. Study findings underscore the importance of housing polices which consider substance use in the context of current and cumulative trauma experiences in order to improve quality of life and mental health for unstably housed women.

Keywords: built environment, SRO hotels, women, trauma, mental health, drug use, ethnography

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the comorbidity of substance use and mental illness is a widely recognized phenomenon at a national level (NIDA, 2008; Volkow, 2006; Conway et al. 2004), specifically among the urban poor (Bassuk et al., 1998, Hien et al., 1997). Epidemiological studies underscore significant gender differences in the presentation of comorbidity, with women more likely than men to be diagnosed with affective and anxiety-related mental health disorders (Diflorio & Jones, 2010; NIDA, 2008). Estimates of depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are disproportionately higher among substance-using, unstably housed women than cohorts of housed women (Nyamathi, Leake, and Gelberg, 2000; El-Bassel et al., 2011; Coughlin, 2011). While research has shown that access to housing may contribute in a significant way to a number of individual mental health outcomes (Baker and Douglas, 1990; Hanrahan et al., 2001; Nagy, Fisher and Tessler, 1998; Earls and Nelson, 1988), there is need to understand how housing policies shape specific built environments, which in turn impact women at risk for poor mental health outcomes and substance abuse. This paper analyzes the role of place, specifically Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotel rooms, in exacerbating and ameliorating negative mental health outcomes for substance using, urban poor women.

Urban housing environments have received increasing attention as sites that can both contribute to health and produce harm (Vlahov, et al., 2007; Freudenberg, Galea, and Vlahov, 2005, Northridge, Sclar & Biswas, 2003), and there is growing evidence linking the built environment to mental health (Halpern, 1995; Evans, 2003; Parr, 2000; Frumkin, 2003). Contributing factors include neighborhood conditions (Cohen, et al., 2003; Dalgard & Tambs, 1997; Wandersman & Nation,1998; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Johnson, Ladd, & Ludwig, 2002), poor housing quality (Evans, Wells, & Moch, 2003; Freeman, 1984), crowding and lack of privacy (Baum & Paulus 1987; Evans & Lepore, 1993; Wener & Keys, 1988), and noise (Stansfeld, 1993), which negatively impact depression (Galea, et al. 2005; Weich et al, 2002), social support (McCarthy & Saegert 1979; Evans & Lepore, 1993) and recovery from cognitive fatigue and stress (Frumkin, 2001; Ulrich, 1991).

Living in an SRO, when compared to living in other housing environments, has been associated with higher rates of HIV infection, emergency room use, recent incarceration, having been physically assaulted, crack cocaine smoking, and cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine injection (Evans & Strathdee, 2006; Shannon et al., 2006). Further, Lazarus et al. (2011) demonstrate that the specific organization and management of SROs creates a gendered vulnerability to violence and sexual risk taking among women. Political-economic theories which account for the role place (Popay, 2003; Rabinow, 2003; Bourgois and Schoenberg, 2009; Fullilove, 2013) have included an analysis of the structural-level policies responsible for the creation of built environments through the use of public funds. Drawing from this example, we adapt Rhodes’ (2002, 2009) “risk environment” framework to argue that SROs can operate as “mental health risk environments” for urban poor women. Consistent with the risk environment framework (Rhodes et al., 2005; Rhodes et al, 2012), our analysis examines the interplay between: 1) housing policies addressing comorbid substance use and mental illness as a macro-level factor shaping the built environments of SROs, 2) meso-level factors such as the management of social relationships within SROs, including drug/sex economy involvement, and 3) micro-level individual behaviors related to drug use and trauma management enacted within SROs.

Our application of the risk environment framework to SROs offers potential contributions in the areas of theory, methodology, and health policy. Theoretically, our analysis foregrounds how specific constructions of urban space may exacerbate women’s co-occurring mental health issues and substance use. Methodologically, we employ qualitative methods to examine the relationship between space, drug use, and mental health to reveal the linkages between housing policies, the socio-structural organization of urban built environments and everyday behaviors. In terms of health policy, our analysis highlights the importance of considering comorbidity in housing policy for active substance users, particularly the role of trauma-sensitive housing environments for unstably housed women who use illicit drugs.

METHODS

Our participants were recruited from a larger epidemiological study, the “Shelter, Health and Drug Outcomes among Women” (SHADOW), a cohort study of homeless and unstably housed women living in San Francisco (Riley et al., 2007). A qualitative sub-sample (n=30) was selected from the larger SHADOW cohort. Consistent with qualitative study designs, the sample was not representative of the larger cohort (Silverman and Marvasti, 2008). Rather, we purposefully sampled (Coyne, 1997; Higginbottom, 1998) women illustrative of a set of issues (recent physical and/or sexual victimization, unprotected sex, and needle sharing) previously described in the epidemiological literature to be relevant to unstably housed women (Coughlin, 2011). Women in the sub-sample underwent a separate consent process and took part in approximately hour-long taped interviews with trained qualitative researchers (Knight, Lopez, and Cohen). During the interviews, participants were asked to describe their current and past living situations, current and past drug use, mental health (including experiences with diagnosis and psychiatric medications), sexual and friendship relationships, and experiences with violence and trauma. Participants completed a baseline, one-year, and 18-month follow up interview and were reimbursed $15 for each interview completed. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco. In addition, the first author (Knight) conducted an independent, four-year (2007–2010) ethnographic study which included interviews with housing and health policy-makers in San Francisco and a photo-ethnographic study of a variety of SRO hotel rooms. Over 500 photographs were taken during this timeframe in 25 different SRO hotels in San Francisco.

Transcribed audio-recorded interviews from each study underwent a similar two-phase analysis, consistent with methods the authors have employed in several previous qualitative studies (Comfort et al., 2005; Knight, et al., 2005; Knight, et al., 1996). In phase one, the team of four analysts (three of whom were the interviewers) used grounded theory methodologies (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) to construct memo summaries of each interview, which included basic background information, current circumstances, notable events and quotations, and analyst impressions and interpretations. Because previous research (Chan, Dennis, & Funk, 2008; Cohen et al., 2009; Hooper, et al., 1997; Kushel et al., 2003; Luhrmann, 2008) indicated a potential relationship between lifetime histories of traumatic exposure, housing instability, current living situations, and sexual and drug use behaviors, we sought to keep narratives “intact” in the initial data analysis phase. The interview transcript and summaries were then discussed at a 2-hour meeting devoted to analyzing each participant’s interview. The team identified each narrative’s micro, meso, and macro factors for analysis. After the initial group analysis process, the team developed a preliminary codebook, which was amended throughout data collection. In phase two of analysis, interview transcripts were coded and entered into a qualitative data management software program (www.Transana.org), to produce aggregate data for the entire qualitative sample. For the purposes of this analysis, memoed summaries and multiple aggregate sections of coded data (e.g., codes for housing, trauma, mental health, neighborhood) were analyzed. Photo-ethnographic data were coded by location, type of hotel, and date.

RESULTS

Macro-level factors: housing policies shape SRO built environments in San Francisco

The widespread implementation of mental health deinstitutionalization policies which took place in the 1970’s and 80’s in California was not accompanied by structured housing plans for the uptake of mentally ill persons now residing in the community (Lamb, 1984). Thus, community reintegration of adults with disabling mental illnesses created a housing need, which was largely unmet. One policy maker outlined the statistics on co-morbidity among the population in San Francisco, underscoring the relationship between drug use, place, and social policy in this setting:

Of the people in supportive housing in San Francisco, 93% have a major mental illness that we can name. That is very, very high. 80% use cocaine, speed, or heroin every thirty days, or get drunk to the point of unconsciousness. There are no more disabled people in this country.

Because of San Francisco’s small size and geographic boundedness, it was expedient to use existing SROs as sites to house the burgeoning urban poor. To date, there are more than 500 SROs in San Francisco, providing homes for approximately 30,000 low income individuals (CCSRO website). These built environments include both larger and smaller building stock, with some SRO hotels housing up to 200 persons and others with only 25–30 rooms. The necessity of using existing SRO housing as sites to accommodate the expanding population of impoverished individuals created a trifurcated system. This system has led some women to find housing in older, privately run and managed SROs, some in previously privately-owned buildings whose master lease had been purchased by the City of San Francisco, and other to be housed in new buildings built on the demolished cites of older SROs or in other urban spaces1. These three types of built environments presented different challenges to women in the management of their mental health.

The department of Housing and Urban Health (HUH), the first in the country to formally integrate housing management with public health, was created within the San Francisco Department of Public Health to develop and manage the publically funded older and newer SRO buildings. The HUH discovered through the course of this progressive housing initiative that building new, publically-funded SROs is more cost effective and produces better housing and health outcomes for the tenants, than converting exiting privately owned SROs. Even if rental payments could be deferred through welfare or subsidy payment mechanism, simply placing adults indoors in older SRO building was not efficacious if the indoor environment was still chaotic, dangerous, and poorly managed. At the macro-level, the built environment needed to be responsive to “trauma.”2 For a population of tenants with such high rates of co-morbid substance use and mental health issues, the built environment – the organization of the physical and social space – was construed as critical to ensuring housing success. One health and housing policy maker compared the different levels of housing stability for tenants in new SRO built environments to those in older SROs, to emphasize the interactive relation between the built environment and trauma:

When we look at our success in keeping people housed in our buildings, what we see is that places like the Marque3, which has small, dirty rooms, case management, but shared bathrooms. The rate of people staying housed there for two years consecutively is 30%. That is horrible. The Zenith, a new building, has case management, same as the Marque. But it is beautiful; every room has its own bathroom. 70% of the tenants stay at least two years.” The point is the good stuff is the better investment when it comes to supportive housing. The environment matters. I think it is about trauma. People, who have had so much trauma cannot stabilize, cannot stay housed if they still living in a dump.

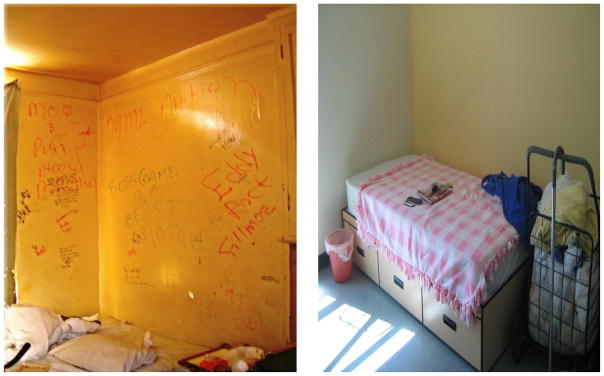

The following pictures draw a comparison between the physical environment deemed to be “trauma-sensitive” and a standard situation from a privately-owned SRO. The physical layout of a typical SRO is a single, 8x10″ room with shared toilets and showers down the hallway. Newly built SROs were often clean, less chaotic, well-managed, and safer. Newer SROs included individual bathrooms and sometimes small kitchens to prepare food. In contrast, older and privately-owned SROs often consisted of a double or single bed, a sink, a small chest of drawers, and a desk. The physical conditions which routinely affected women’s mental health in our study included the presence of rats, mice, and bed bugs; graffitied walls and broken furniture; and, non-operating sinks, electricity, door locks, and TV sets. As demonstrated in the photos, the condition and functionality of the physical aspects of the built environment varied a great deal and this variation contributed in positive and negative ways to women’s mental health outcomes.

Meso and micro-level factors: social relations and behavioral strategies intersect with the built environment to influence mental health

The women in our sample had high rates of co-occurring mental health and substance use issues and extensive histories of childhood and adult sexual and physical victimization, making the management of trauma symptoms an everyday life challenge. One woman described the impact her new calm, controlled environment had on her risk for poor mental health:

I discovered that my environment had a lot to do with my mental state. So, when I had my own place, I was in control of the environment. You know, there was no drama, everything was nice and mellow, and so I was able to function. Everything was on an even keel; that was fine. It was when other people and situations were introduced into my environment that I couldn’t get away from, that would send me over the edge.

The physical and social organization of specific SRO housing environments made such a significant impact on the women in our studies that many reported choosing street homelessness or homeless shelter stays if they could not secure a room in a monthly rate, clean, and safe SRO. Reinforcing the data provided from the housing policy-maker, one woman described “shopping” for an SRO which meet her mental health needs, rather than accepting the first publically subsidized built environment offered to her.

[The homeless shelter administrator] told me I would find a place [through a subsidized program] if I work with them. And they did find me a lot of places, but I didn’t want to go, because [those] SROs they have now are really nasty. Really tore up, tore down. Syringes in the bathroom. Blood on the toilet. Because you use the same toilet that everybody else uses. So it wasn’t sanitized. So I didn’t want to go. And I found the Martin Hotel and I went in and it was a really clean, nice place. So I went back to [the shelter] and I asked them ‘Can you please get me a place inside that hotel?’ They said that would be cool, they would work on it. And within two, three weeks I had a place at the Martin.

SRO environments where women felt unsafe exacerbated several physical and emotional symptoms associated with poor mental health. The physical organization of SROs, which consisted of crowding people with addiction and mental health issues into a single space. This, in combination with, chaos related to drug/sex economy interactions (drug dealers, runners, pimps and sex workers), and rapid cycling of new tenants contributed to stress-related sleeping problems, hyper-vigilance, and drug and alcohol use. Many women described needing prescription sleep medication to rest in chaotic hotel settings and avoid conflicts with neighbors:

When I go in [to the SRO hotel] and shut my door, I just try to shut my eyes and block it out. Sometimes they [neighbors] have their TVs on and I want to say something. I’m thinking, ‘You know, [says her own name], just be quiet! Just go to sleep.’ Once I take my [sleeping] pills, I’m good.

Women commonly adopted a strategy of deliberate social isolation to shield themselves from risk for victimization within unsafe SRO environments. For some women, isolation in the hotel room was an emotionally self-protective response to living daily in a traumatized state. One woman provided an example of isolation linked to on-going fears of being attacked:

So I started using back in 2009, which I have been using drugs for a year now. I got raped last year. I got raped, I got kidnapped. I was tortured for days. My best friend died, as I told you. It’s just everything fell apart and I have been tore up since then…Since I moved to [my SRO], I basically stay in my room all day.

For others, isolation served as a strategy to avoid being “caught up” in unpredictable violence and social disorder associated with the drug-sex economy:

So, now I’m here, you know, just trying to deal with a lot of different things, you know. Adjustment of being back [in my SRO room] which I’m getting more adjusted to it, but I don’t like the space that I’m in because it’s small. Of course, I don’t mingle with my neighbors either…I just tend to stay to myself because I see trouble there and I avoid that because I don’t need that in my life, you know. So, that’s another thing I deal with on a day-to-day basis you know.

In contrast to the women above who described deliberate social isolation as a mental health survival strategy, another woman positively described increased safety and independence in built environments which were perceived as safe and non-chaotic. For example, one positively described her highly structured SRO housing environment, a place specifically designed to reduce her fear and anxiety over repeated victimization and to enhance her ability to manage her mental health symptoms despite years of trauma and housing instability:

Oh, it’s [my room’s] beautiful, it’s comfortable and it’s quiet and it’s clean! I mean the manager there is up on it. He’s got security cameras now. It’s secure, I’m high up. The only way you can get into my window is if you try to do it. And if you try to do it and you fall, you’re going to die. It’s out of the way [out of the neighborhood], yeah. And so the [public] bus takes me to school. Takes me straight to school, straight home. Boom, no chaos. Walgreen’s right there. Boom, psych meds, boom right there, boom. Bus pass, Walgreen’s right there, boom. Everything’s right there. You know [the bank] is right on the corner, boom. I’m just -- McDonald’s everything, grocery store, laundromat, everything is just right there in my commute. I don’t have to go a block to go to the laundromat. I don’t have to go through a block to go to grocery shopping. So, everything is just perfect for me.

In terms of localized drug policy and housing, the adjudication of in-building drug use was not prioritized by the women in our study to the same extent as other measures taken to ensure the built environment was spatially and socially organized to reduce fear, anxiety, and conflict. While women acknowledged the risks that the drug-sex economy posed to their mental health, many also actively participated in those economies as drug users and (intermittently) as sex workers. Even women who were seeking to reduce or eliminate their own drug use, or who were abstinent, did not suggest that drug use or sex work should be outlawed within their hotels to promote safety. Opinions veered towards a “closed-door” policy, particularly about drug use. Women expressed that, ideally, open-air drug markets and the street-level chaos and violence often associated with the drug-sex economy should be mitigated by the hotel management, thereby promoting safety and control within the housing environments. In one example, several women in our study positively described an active campaign by SRO management, which evicted drug-dealing tenants from the building. Drug-using tenants were not targeted; however, those participating in the economy that brought associated violence and social disturbance were systematically removed. In another example, a crack and heroin-using woman described her building as safe, had friendships with neighbors in the hotel, and could list several examples of how her hotel manager helped her and other tenants. “We don’t have an open-air drug market here,” she noted. At the macro-level, policy maker data supported the view that many women held indicating that drug use adjudication is not necessarily the key area of intervention for SRO built environments. One policy maker indicated that the drug-sex economy is very active in one hotel, while the duration of tenant occupancy is still high.

Actually in our building that has the highest success rate [80% of tenants stay housed there at least two years]; there is a ton of sex work and drug use. And yet people stay housed. I am arguing the financial argument. The cost effective argument: ‘If you spend the money here – on beautiful new supportive housing and you will reduce costs.’

Both policy maker and women’s data concurred that supportive housing could succeed in a cost effective manner, even if all problematic aspects of the drug/sex economy are not abated, as long as the built environments are designed with sensitivity toward the mental health vulnerabilities of tenants, clean, and well-managed.

DISCUSSION

Access to affordable housing is a key drug policy issue for the urban poor in the United States. Due to the high levels of comorbid substance use and mental illness, access to housing cannot be divorced from discussions of “place” - the construction and quality of built environments designed and funded to house at-risk urban populations of substance users. Critical debates over the use of public funds to physically construct and manage public housing that is responsive to the complex needs of drug users with mental health challenges requires knowledge of the macro-structural factors, meso-level social interactions of everyday living, and micro-behavioral mental health management among tenants. Our analysis applies Rhodes et al.’s framework of socio-structural vulnerability, to explore how SROs can operate as “mental health risk environments” that impact women’s mental health.

Low-income and homeless women have higher lifetime and current rates of major depression and substance abuse when compared to women in the general population (Bassuk et al., 1998). Historically, a burgeoning homeless population and a public policy commitment to create housing opportunities for people with co-occurring mental health diagnoses and substance use led to SROs becoming the default housing stock for the urban poor in San Francisco. The conditions and characteristics of these built environments contributed to and/or exacerbated poor mental health among women in our studies. Our findings show that in SROs that were reorganized through physical and managerial changes, women residents with histories and current vulnerabilities to trauma experienced greater stabilization. In non-trauma-informed SRO environments women reported on-going fear and anxiety, sleep deprivation and hyper-vigilance. Our findings support other research indicating that the type, availability, and the material conditions of housing environments play a significant role in mental health (O’Campo, Salmon, & Burke, 2009; Galea, et al., 2005), especially for women (Epele, 2002; Evans, 2003). In terms of housing policy for substance using urban populations, our research suggests that public fund investment in SRO built environments which secure the physical and emotional safety of comorbid women tenants should be a key priority to alleviate chronic homelessness and reduce further victimization.

Figure 1.

older SRO room compared to newly built SRO room;

Figure 2.

view of newly built SRO compared to view out of older SRO;

Figure 3.

newly built SRO hallway compared to older SRO hallway.

Footnotes

The payment structure for rent in these three types of SROs is complex and varies for tenants depending on whether they pay for SRO rooms out of pocket, or through welfare program linked subsidies, of which there are several. Discussion of the complex payment structures is beyond the scope of this paper, but is discussed at length in a forthcoming publication. See Knight, KR Limited Addiction: Pregnancy and Madness in the Daily-rent Hotels, forthcoming with Duke University Press.

“Trauma” here is a colloquial (as opposed to clinical) term deployed to refer to the complex array of affective symptoms many chronically-homeless persons, especially women, demonstrate in daily life as a result of historic experiences of abuse and current vulnerabilities.

The names of SRO hotels are pseudonyms.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baker F, Douglas C. Housing Environments and Community Adjustment of Severely Mentally Ill Persons. Community Mental Health Journal. 1990;26(6):497–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00752454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Paulus PB. Crowding. In: Stokols D, Altman I, editors. Handbook of Environmental Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. pp. 533–570. [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Buckner JC, Perloff JN, Shari S, Bassuk SS. Prevalence of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders Among Homeless and Low-Income Housed Mothers. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1561–1564. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Schonberg J. Righteous Dopefiend. University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Central City SRO Collaborative (CCSRO), San Francisco. History of SROs in San Francisco. [Accessed on the web January 20, 2010]. no date. [Google Scholar]

- Chan YF, Dennis ML, Funk RL. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LR, Tross S, Pavlicova M, Hu MC, Campbell AN, Nunes EV. Drug Use, Childhood Sexual Abuse, and Sexual Risk Behavior among Women in Methadone Treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(5):305–310. doi: 10.1080/00952990903060127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Mason K, Bedimo A, Scribner R, Basolo V, Farley T. Neighborhood Physical Conditions and Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(3):467–471. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comfort M, Grinstead O, McCartney K, Bourgois P, Knight K. You cannot do nothing in this damn place”: sex and intimacy among couples with an incarcerated male partner. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(1):3–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton W, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Lifetime comorbidity of DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders and specific drug use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):247–257. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS. Co-occurring health conditions among women living with profound life challenges. Am J Epidemiology. 2011;174(5):523–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne IT. Sampling in Qualitative Research. Purposeful and Theoretical Sampling; Merging or Clear Boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:623–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.t01-25-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard OS, Tambs K. Urban environment and mental health: a longitudinal study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:530–536. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diflorio A, Jones I. Is sex important? Gender differences in bipolar disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(5):437–52. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.514601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epele ME. Gender, violence and HIV: women’s survival in the streets. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2002;26:33–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1015237130328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls M, Nelson G. The Relationship between Long-Term Psychiatric Clients’ Psychological Well-Being and Their Perceptions of Housing and Social Support. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1988;16(2):279–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00912527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Vinocur D, Chang M, Wu E. Posttraumatic stress disorder and HIV risk among poor, inner-city women receiving care in an emergency department. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):120–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Lepore SJ. Household crowding and social support: a quasi-experimental analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:308–316. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. The Built Environment and Mental Health. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536–555. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Wells NM, Moch A. Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J Soc Issues. 2003;59:475–500. [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, Strathdee SA. A roof is not enough: Unstable housing, vulnerability to HIV infection and the plight of the SRO. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman HL. Housing. In: Freeman HL, editor. Mental Health and the Environment. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. pp. 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Galea S, Vlahov D. Beyond urban penalty and urban sprawl: back to living conditions as the focus of urban health. J Community Health. 2005;30(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-6091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin H. Beyond toxicity: human health and the natural environment. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:234–240. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin H. Health places: exploring the evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93( 9):1451–1456. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove M. Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities. New Village Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Rudenstine S, Wallace Z, Vlahov D. Urban built environment and depression: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(10):822–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.033084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern D. Mental Health and the Built Environment: More Than Bricks and Mortar? Taylor & Francis; Abingdon: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ, Savage C, Goldman HH. Housing Satisfaction and Service Use by Mentally Ill Persons in Community Integrated Living Arrangements. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1206–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Zimberg S, Weisman S, First M, Ackerman S. Dual diagnosis subtypes in urban substance abuse and mental health clinics. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(8):1058–63. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom GMA. Sampling Issues in Qualitative Research. Nurse Researcher. 2004;12:7–19. doi: 10.7748/nr2004.07.12.1.7.c5927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K, et al. Homelessness, Severe Mental Illness, and the Institutional Circuit. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:659–65. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ladd HF, Ludwig J. The benefits and costs of residential mobility programs for the poor. Housing Stud. 2002;17:125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Knight KR, Rosenbaum M, Kelley MS, Irwin J, Washburn A, Wenger L. Defunding the poor: the impact of lost access to subsidized methadone maintenance treatment on women injection drug users. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26(4):923–942. [Google Scholar]

- Knight KR, Purcell D, Dawson-Rose C, Gómez CA, Halkitis PN the SUDIS Team. Sexual risk taking among HIV-positive injection drug users: contexts, characteristics, and implications for prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;S17(1):76–88. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.76.58692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, et al. No door to lock: victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2492–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R. Deinstitutionalization and the Homeless, Mentally Ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1984;35(9):899–907. doi: 10.1176/ps.35.9.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L, Chettiar J, Deering K, Nabess R, Shannon K. Risky health environments: Women sex workers’ struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada’s poorest postal code. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73(11):1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrmann TM. The street will drive you crazy”: why homeless psychotic women in the institutional circuit in the United States often say no to offers of help. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(1):15–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D, Saegert S. Residential density, social overload, and social withdrawal. In: Aiello J, Baum A, editors. Residential Crowding and Design. New York, NY: Plenum; 1979. pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy M, Fisher G, Tessler R. Effects of Facility Characteristics on the Social Adjustment of Mentally Ill Residents of Board-and-Care Homes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(12):1281–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.12.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. NIH Publication Number 08–5771. 2008. Comorbidity: Addiction and Other Mental Illnesses NIDA Research Report Series. [Google Scholar]

- Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:556–568. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Leake B, Keenan C, Gelberg L. Type of Social Support Among Homeless Women: Its Impact on Psychosocial Resources, Health and Health Behaviors, and Use of Health Services. Nursing Research. 2000;49(6):318–326. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Salmon C, Burke J. Neighbourhoods and mental well-being: what are the pathways? Health and Place. 2009;15:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr H. Interpreting the ‘hidden social geographies’ of mental health: ethnographies of inclusion and exclusion in semi-institutional places. Health & Place. 2000;6 (3):225–237. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Thomas C, Williams G, Bennett S, Gatrell A, Bostock L. A proper place to live: health inequalities, agency and the normative dimensions of space. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow P. Ordonnance, Discipline, Regulation: Some Reflections on Urbanism. In: Low Setha, Lawrence-Zuniga Denise., editors. The Anthropology of Space and Place: Location Culture. Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. (2009) International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(5):1026–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: Theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In: O’Campo P, Dunn JR, editors. Rethinking social epidemiology: Towards a science of change. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2012. pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Weiser SD, Sorensen JL, Dilworth S, Cohen J, Neilands TB. Housing Patterns and Correlates of Homelessness Differ by Gender among Individuals Using San Francisco Free Food Programs. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3):415–422. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Francisco Department of Public Health, Housing and Urban Health (HUH) [Accessed February 2013];Direct Access to Housing Program. website. http://www.sfdph.org/dph/comupg/oprograms/DAH/

- Shannon K, Ishida T, Lai C, Tyndall M. The impact of unregulated single room occupancy hotels on health status of illicit drug users in Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17 (2):107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D, Marvasti A. Doing Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld SA. Noise, noise sensitivity, and psychiatric disorder: epidemiological and psychophysiological studies. Psychol Med, Monogr Suppl. 1993;22:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness: theory and recent scientific research. J Health Care Interior Design. 1991;3:97–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Freudenberg N, Proietti F, Ompad D, Quinn A, Nandi V, Galea S. Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i16–26. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND. The reality of comorbidity: Depression and drug abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Nation M. Urban neighborhoods and mental health. Am Psychol. 1998;53:647–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S, Blanchard M, Prince M, Burton E, Erens B, Sproston K. Mental health and the built environment: cross sectional survey of individual and contextual risk factors for depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;176:428–433. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wener RE, Keys C. The effects of changes in jail population densities on crowding, sick call, and social behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1988;18:852–866. [Google Scholar]