Abstract

Background. Pneumococcal serotypes are represented by a varying number of clonal lineages with different genetic contents, potentially affecting invasiveness. However, genetic variation within the same genetic lineage may be larger than anticipated.

Methods. A total of 715 invasive and carriage isolates from children in the same region and during the same period were compared using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing. Bacterial genome sequencing, functional assays, and in vivo virulence mice studies were performed.

Results. Clonal types of the same serotype but also intraclonal variants within clonal complexes (CCs) showed differences in invasive-disease potential. CC138, a common CC, was divided into several PFGE patterns, partly explained by number, location, and type of temperate bacteriophages. Whole-genome sequencing of 4 CC138 isolates representing PFGE clones with different invasive-disease potentials revealed intraclonal sequence variations of the virulence-associated proteins pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) and pneumococcal choline-binding protein C (PspC). A carrier isolate lacking PcpA exhibited decreased virulence in mice, and there was a differential binding of human factor H, depending on invasiveness.

Conclusions. Pneumococcal clonal types but also intraclonal variants exhibited different invasive-disease potentials in children. Intraclonal variants, reflecting different prophage contents, showed differences in major surface antigens. This suggests ongoing immune selection, such as that due to PspC-mediated complement resistance through varied human factor H binding, that may affect invasiveness in children.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, pneumococcal infections, invasive disease potential, intraclonal variation, surface proteins, bacteriophages, factor H binding, PspA, PspC, PcpA

(See the editorial commentary by Klugman et al on pages 321–2.)

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a human-adapted commensal pathogen colonizing the nasopharynx in up to 60% of preschool children [1, 2]. Even though invasive disease is an unlikely event of infection, this organism is estimated to cause the death of >800 000 children <5 years of age worldwide annually [3]. Epidemiological studies have revealed that pneumococci expressing particular capsular serotypes dominate in invasive pneumococcal disease among children, and it is against such pediatric serotypes that polysaccharide-conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have been directed. Comparisons of the prevalence of carriage and invasive isolates within the same geographical area and period demonstrate that particular serotypes (ie, those with a high invasive-disease potential) are associated with a higher potential than others to cause invasive disease [4–6].

It has been difficult to demonstrate whether different clonal lineages of pneumococci, independent of capsular type, differ in their ability to cause invasive disease. One reason is that many serotypes, including those with a high invasive-disease potential, such as serotypes 1, 4, and 7F, belong to only 1 or a few dominating genetic lineages [5, 7, 8]. Among serotypes with a low invasive-disease potential, such as serotype 19F, many different genetic lineages are found, but since the number of isolates representing each lineage usually is low the study has to be sufficiently large to demonstrate statistical significance. The same holds true for genetic lineages that may appear with different capsules, such as clonal complex 156 (CC156) [9].

Because of the highly recombinogenic nature of pneumococci, different isolates belonging to the same genetic lineage, as determined by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), may differ from one another in gene content [10, 11]. Therefore, even within the same genetic lineage, there may be specific subclones or variants with a higher capacity than others to cause invasive disease. Deletions, insertions, and DNA rearrangements are expected to create differences in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns among isolates belonging to the same genetic lineage as determined by MLST.

In this study, we examined a large set of nasopharyngeal carriage and invasive pneumococcal isolates recovered from children from the Stockholm area during 1997–2004. We calculated the odds ratio (OR) for causing invasive disease and found that different clonal types but also intraclonal variants may exhibit different invasive-disease potentials. Pneumococcal isolates representing intraclonal variants of the most prevalent clonal lineage with different disease outcomes in children were characterized genetically and functionally.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Isolates Studied

Nasopharyngeal carriage pneumococcal isolates (n = 550) and invasive pneumococcal isolates (n = 165) were recovered from children (<18 years of age) during 1997–2004 from the Stockholm area. The mean age was 2.5 years for children with invasive pneumococcal disease and 3.3 years for healthy carriers.

Serotyping

All 715 isolates were serotyped using gel diffusion with 46 serotype/group antisera obtained from Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, Denmark [2].

PFGE Analysis

All invasive and carriage isolates from children were subjected to PFGE adapted from the procedure described by Hermans et al [12]. The clones were defined by using the criteria described by Tenover et al [13].

MLST Analysis

A total of 200 isolates—165 invasive isolates from children and 35 representatives of clonal types found with PFGE among the carriage isolates—were subjected to MLST analysis. MLST was performed according the procedure described by Enright et al [10]. The sequences obtained were submitted to the MLST database (available at: http://www.mlst.net) and assigned a sequence type (ST). The isolates were assigned to different clonal complexes (CCs), as defined on the basis of the entire collection of isolates within the MLST database [14], using an algorithm on the MLST Web site from 2008 [15]. In brief, a CC is defined as a group of STs in a population that shares 6 of 7 alleles with at least 1 other ST in the group. Isolates belonging to a CC may be assumed to have a recent common ancestor [15]. For isolates without MLST data, we assigned a CC to those that belong to a PFGE clone for which the MLST is available for at least 1 isolate.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for pcpA and Typing of Prophage DNA

PCR was performed as previously described [9]. The presence of pcpA was determined using specific primers from the coding region (Supplementary Table 1). The presence of phage genes and individual phage typing was determined as described by Romero et al [16].

Lysogenic Bacteriophage Induction by Use of Mitomycin C

The protocol was adapted from the report by Romero et al [16]. In brief, S. pneumoniae isolates were grown in C + Y medium at 37°C until the culture reached an optical density (OD) at 620 nm of 0.2. Mitomycin C was added to a final concentration of 100 ng/mL to induce release of temperate bacteriophages. Growth was monitored in microtiter plates (5 replicate wells/isolate) with Bioscreen equipment (Labsystems, Finland). Measurements were made at OD600 every fifth minute for 16 hours.

Sequencing of pspC and pspA

Sequencing of pspC1 was performed for 4 serotype 6B isolates, and sequencing of pspC2 and pspA was performed for 14 and 12 serotype 6B isolates, respectively, as described previously [17, 18].

Whole-Genome Shotgun Sequencing

Whole-genome shotgun sequencing was performed on 4 serotype 6B isolates (BHN237, BHN427, BHN418, and BHN191). Chromosomal DNA was prepared using a Qiagen DNA prep kit (Genomic DNA Buffer Set and Genomic-tip 100/G). The DNA was subjected to sequencing using a Roche Genome Sequencer FLX (GS FLX). Assembly of the 454 data was performed using Newbler v 2.3 [19]. Genes were predicted using GeneMark.hmm prokaryotic, version 2.6p [20]. To align the contigs to the reference genome, MUMmer [21] was used; to visualize the data, Artemis Comparison Tool was used [22]. Results of this whole-genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession number ASHQ00000000.

Factor H (FH) Binding by Use of Far Western Blot and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Analyses

Strains were grown in C + Y medium to an optical density at 620 nm of 0.6 and harvested by centrifugation. Bacterial pellets were lysed by boiling in 1 × Nupage sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading solution (Invitrogen). The samples containing 15 µg of proteins from whole-cell lysate of pneumococci (quantified by Bradford Reagent, Sigma-Aldrich) were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated with 1 µg/mL human FH, followed by incubation with goat anti-FH antibody (1:2000 dilution; Calbiochem) and with rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP; 1:8000 dilution; Invitrogen). Detection was performed using the ECL prime Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare) and developed using Gel-doc (Biorad).

FH binding was also quantified using whole-cell ELISA. Microtiter plates were coated overnight with 5 µg/mL FH at 4°C. Subsequent steps were conducted at room temperature for 2 hours each. After washes with 0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 1% skim milk in PBS and washed again, and 2 × 106 bacteria were added. Bound bacteria were detected using a 6B specific polyclonal anticapsule (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark) diluted 1:1000 in 0.1% BS and anti-rabbit-HRP. SigmaFast OPD (Sigma) was used for detection, and absorbance was measured at 492 nm. Three different experiments were done in triplicate.

Animal Model

C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU). Blood samples were collected every 24 hours, and the bacterial load in lungs was determined at the time of euthanization. The experiments were approved by the local ethics committee (Stockholms Norra djurförsöksetiska nämnd).

Statistical Analysis

ORs were calculated to estimate the potential of causing invasive disease for different serotypes and clonal types, as follows: OR = [ad]/[bc], where a the number of invasive clone X isolates, b is the number of carriage clone X isolates, c is the number of invasive clone non-X isolates, and d the number of carriage clone non-X isolates. ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Fisher method implemented in the Epitools package for statistical software R, version 2.13.0 (available at: http://www.r-project.org). An OR of >1, along with a 95% CI that did not include 1, indicated an increased risk for causing invasive disease.

The data from animal experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 software. Survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test, and blood CFU data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All 715 invasive and carriage isolates were subjected to serotyping and molecular typing to study genetic relatedness, using PFGE and/or MLST (Table 1). The nomenclature for PFGE variants indicates a particular pattern within the dominating serotype, whereas the MLST data allow grouping of isolates into different CCs. The ORs for invasive disease were calculated for each PFGE pattern and are given in Table 1. Isolates belonging to CCs associated with the highest invasive-disease potential (CC306, CC205, and CC191) were represented by isolates belonging to mainly 1 serotype (types 1, 4, and 7F, respectively).

Table 1.

Odds Ratio (OR) of Clonal Types Determined Using Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

| Isolates, No. |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFGE clone | Total | Invasive | Carriage | Other serotypes | CCa | OR (95% CI) | Comment |

| SWE14-6b | 7 | 7 | 0 | - | 15 | ∞ (4.94-∞) | All invasive |

| SWE11A-1 | 13 | 3 | 10 | - | 62 | 1.00 (0.17-3.95) | |

| SWE19F-5 | 8 | 0 | 8 | - | 63 | 0.00 (0.00-1.95) | All carriage |

| SWE18C-1 | 17 | 2 | 15 | 10A,6A, 18B | 113 | 0.44 (0.05-1.91) | |

| SWE18C-3b | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6B | 113 | 17.07 (1.89-809.23) | |

| SWE14-2 | 14 | 3 | 11 | - | 124 | 0.91 (0.16-3.49) | |

| SWE14-3b | 8 | 5 | 3 | - | 124 | 5.68 (1.09-36.97) | |

| SWE14-4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | - | 124 | 1.67 (0.15-11.8) | |

| SWE23F-2 | 21 | 4 | 17 | 19A, 19F, 35F | 124 | 0.78 (0.19-2.44) | |

| SWE6B-1 | 61 | 16 | 45 | 6A | 138 | 1.20 (0.62 -2.25) | |

| SWE6B-2 | 34 | 9 | 25 | - | 138 | 1.21 (0.49-2.75) | |

| SWE6B-3b | 7 | 6 | 1 | 6A | 138 | 20.62 (2.47-949.68) | |

| SWE14-1 | 23 | 3 | 20 | 9V,19F | 156 | 0.49 (0.09-1.69) | |

| SWE3-1 | 12 | 2 | 10 | - | 180 | 0.66 (0.07-3.16) | |

| SWE7F-1b | 18 | 12 | 6 | - | 191 | 7.09 (2.41-23.4) | |

| SWE14-5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 19A | 199 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE19A-1 | 25 | 6 | 19 | 19F, 15B, 15C | 199 | 1.05 (0.34-2.81) | |

| SWE4-1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6A | 205 | 6.78 (0.96-75.51) | |

| SWE19F-6 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | 271 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE19F-7 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | 271 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE1-1b | 14 | 13 | 1 | - | 306 | 46.68 (6.91-1977.78) | |

| SWE19F-4 | 11 | 0 | 11 | - | 309 | 0.00 (0.00-1.32) | All carriage |

| SWE38-1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | - | 393 | 0.00 (0.00-2.83) | All carriage |

| SWE16F-1 | 16 | 2 | 14 | - | 414 | 0.47 (0.05-2.08) | |

| SWE19F-2 | 7 | 1 | 6 | - | 425 | 0.55 (0.01-4.61) | |

| SWE23F-1 | 29 | 4 | 25 | 19A | 439 | 0.52 (0.13-1.54) | |

| SWE23F-3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | 439 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE6A-4 | 14 | 2 | 12 | - | 460 | 0.55 (0.06-2.51) | |

| SWE6A-9 | 8 | 0 | 8 | - | 460 | 0.00 (0.00-1.95) | All carriage |

| SWE6A-8 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | 473 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE6A-1 | 22 | 4 | 18 | - | 490 | 0.73 (0.18-2.27) | |

| SWE6B-4 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | 553 | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE19A-2b | 7 | 5 | 2 | - | NPF | 8.53 (1.38-90.45) | |

| SWE19F-1 | 9 | 0 | 9 | - | NPF | 0.00 (0.00-1.68) | All carriage |

| SWE19F-9 | 8 | 0 | 8 | - | NPF | 0.00 (0.00-1.95) | All carriage |

| SWE35B-1 | 11 | 0 | 11 | - | NPF | 0.00 (0.00-1.32) | All carriage |

| SWE35F-1 | 6 | 0 | 6 | - | NPF | 0.00 (0.00-2.83) | All invasive |

| SWE6A-2 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | NC | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE19F-3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | NC | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| SWE19F-8 | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | NC | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| NT | 5 | 0 | 5 | - | NC | 0.00 (0.00-3.64) | All carriage |

| Otherc | 211 | 45 | 166 | 0.87 (0.57-1.30) | |||

| Total | 715 | 165 | 550 | ||||

PFGE clones representing ≥5 isolates are shown. A PFGE clone was given its name according to the most prominent serotype in the clone.

Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; NC, nonconclusive; NPF, no predicted founder.

a CCs are named after the predicted founder as of the 2008 Mars Project in the MLST database.

b Significantly associated with invasive disease.

c PFGE clones with <5 isolates belonging to serotype 6A, 19F, 6B, 23F, 14, 10A, 9 V, 18C, 35F, NT, 3, 21, 11A, 23A, 9N, 15B, 7F, 19A, 33F, 16F, 23B, 4, 8, 31, 38, 11B, 15C, 17F, 22F, and 24F, in decreasing order.

The results presented in Table 1 suggest that isolates with different PFGE patterns and/or different CCs differ in their OR for causing invasive disease. Thus, isolates of PFGE SWE14-6 belonging to CC15 (all serotype 14) had a higher invasive-disease potential than serotype 14 isolates of CC124 (PFGE SWE23F-2, SWE14-2, SWE14-3, and SWE14-4) and CC156 (39% of serotype 14; Table 1). For serotype 19F, a multitude of different PFGE types and CCs were found, and the 3 isolates of PFGE pattern SWE19F-10 (CC251; data not shown) were solely from individuals with invasive disease. The other PFGE clones of serotype 19F belonged to different CCs and were almost exclusively found among healthy carriers (Table 1). These findings suggest that the invasive-disease potential for a serotype can be affected by its clonal distribution within that serotype.

Of particular interest was the presence of different PFGE patterns with different invasive-disease potentials belonging to the same genetic lineage (CC) and serotype, as exemplified for CC138 (type 6B), CC124 (type 14), and CC113 (type 18C; Table 1).

Comparative Genomics on CC138 Isolates Reveal Important Differences That May Influence Disease Outcome

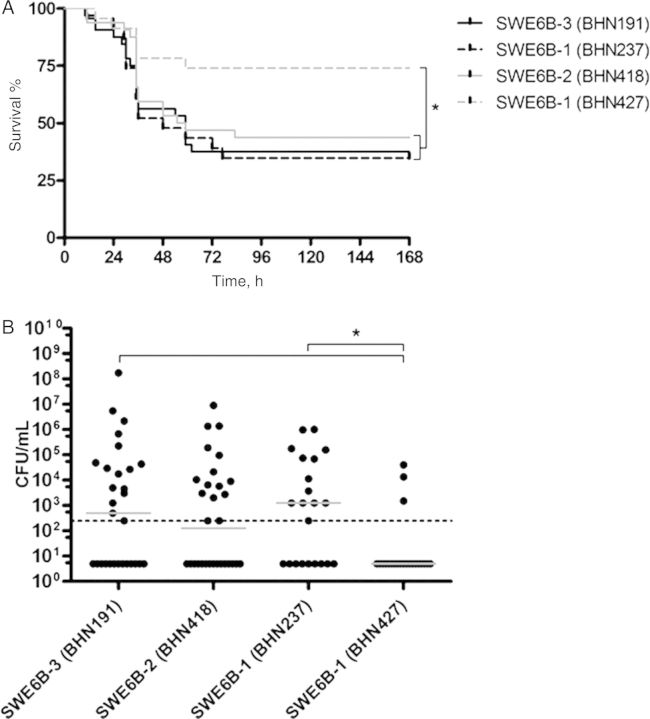

CC138 was the most common genetic lineage among children with invasive disease and healthy carriers; this CC was observed in 110 isolates, of which 107 were of serotype 6B. One subclone, SWE6B-3 by PFGE, belonging to CC138 showed a high OR for causing invasive disease, in contrast to 2 other CC138 subclones, SWE6B-1 and SWE6B-2 (Table 1). Four serotype 6B isolates representing these 3 PFGE patterns with different invasive-disease potentials were selected for whole-genome sequencing (Figure 1A and 1B and Tables 1 and 2). The invasive isolate BHN191 represented SWE6B-3, strongly associated with invasive disease, while carriage isolate BHN418 came from the less invasive SWE6B-2. SWE6B-1 was represented by BHN237 from an individual with invasive disease and by BHN427 from a healthy carrier.

Figure 1.

Genomic differences between (A) invasive BHN191 from SWEB-3 and carriage BHN418 from SWEB-2 and (B) between invasive BHN237 and carriage BHN427, both from SWE6B-1.

Figure 2.

Factor H binding to the 4 strains of 6B and clonal complex 138, using Far Western blotting.

Intraclonal Variations in the Presence, Location, and Function of Prophages

The pneumococcal genome contains a large number of accessory regions (ARs), defined as at least 3 consecutive genes only present in a subset of clinical isolates [7]. The 4 CC138 isolates contained roughly the same ARs. The 2 exceptions were AR13, encoding a putative type 1 restriction system, which was missing in BHN237 and BHN427, and AR29, encoding a putative ABC transporter in which about two thirds of the genes were present in BHN237 and BHN427 but missing in the other isolates. Our previous identification of ARs [7] was based on the TIGR4 and R6 genomes, both of which lack prophages. However, pneumococcal prophages are common [16] and represent large segments of integrated DNA that might affect PFGE patterns in otherwise genetically related strains. Analyses of the 4 genomes revealed that 3 of the 4 CC138 isolates carried clustered genes homologous to identified prophage genes of pneumococci and commensal streptococci. Only carrier isolate BHN418 of SWE6B-2 lacked integrated prophage DNA (Figure 1A and 1B; data not shown). Phages of group 3 were present in the 2 invasive isolates BHN191 and BHN237, each located between the genes homologous to the TIGR4 genes SP_0020 and SP_0021. These 2 group 3 phages were very similar in the 2 invasive isolates, with an overall nucleotide sequence identity of 92% (counted over aligned sequences but not including sequence areas between contigs where sequence information is lacking). The sequence identity varied over the phage genome and over areas covering 89% of the phage sequence, and the nucleotide identity was 97%. Phages of group 2 were found in the 2 isolates of SWE6B-2 (BHN237 and BHN427) and were also similar but not identical in the 2 genomes (82% nucleotide sequence identity over alignable areas). BHN191 belonging to SWE6B-3 contained a second prophage that did not correlate with any of the 3 phage groups described by Romero et al [16], but similar sequences can be found in the 2 sequenced isolates SP19-BS75 and JJA (GenBank accession numbers ABAF00000000 and CP000919). In both BHN191 and JJA, the phage is located between TIGR4 genes SP_1908 and SP_1909.

To further investigate the possible role of the prophages in intraclonal variation and invasive-disease potential, we next studied the presence of phages in all serotype 6B isolates by PCR and performed functional assays of lysogeny by phage induction using mitomycin C [16] (Table 2). All isolates belonging to SWE6B-3 (all but 1 were invasive isolates) and 58 of 61 isolates belonging to SWE6B-1 (invasive and carrier isolates) were shown to harbor at least 1 phage type, with phage group 3 being the most prominent, whereas prophages were absent in most (25 of 34) isolates belonging to SWE6B-2 (the majority of which were carrier isolates). Isolates that had a lysogenic phage (Table 2) were also positive by PCR. However, we found lysogenic isolates that did not fully react with any of the 3 phage group–specific PCR primers, suggesting that there are additional phage groups present. Also, some isolates reacted positively with use of phage-specific primers, even though no phage induction was seen with mitomycin C, suggesting the presence of incomplete prophages. For SWE6B-2, we noted that 4 of the 6 isolates harboring inducible phages were invasive isolates, but we found no correlation as such between the presence of phage DNA and either carriage or invasive disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of All Isolates Belonging to Serotype 6B

| BHN | Serotype | PFGE | ST | CCa | Invasive or Carriage | Phage Group(s)b | Mitomycin C–Induced Lysis | pcpAc | pspAd | pspC1e | pspC2e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHN 191f | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2, clade 3 | PspC6.9 | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 328 | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 387 | 6A | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 238 | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 249 | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 250 | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 460 | 6B | SWE6B-3 | 138 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | … |

| BHN 273 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 176 | 138 | I | Unclassified | + | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 212 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | − | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 259 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | 2 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 305 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 310 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 217 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 379 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 381 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 386 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | I | 3 | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 461 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 462 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 463 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 418f | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam1, clade 1 | PspC6.9 | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 464 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 465 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 466 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 467 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | − | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 468 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | − | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 469 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 470 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 471 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | − | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 510 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | PspC9.4 |

| BHN 50 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 176 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 472 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 176 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 473 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 176 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 543 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 544 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 545 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 546 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 547 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 548 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 549 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 550 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 138 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 474 | 6B | SWE6B-2 | 176 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 237f | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 2, 3 | + | + | Fam1, clade2 | PspC6.1 | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 314 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 382 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 3 | − | + | … | … | … |

| BHN 200 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | − | − | − | Fam2, clade 5 | … | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 322 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 264 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 269 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 287 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 307 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 296 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 333 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 248 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 253 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 300 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | I | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 266 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 171 | 138 | I | 3 | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 271 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 138 | 138 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 427f | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 2 | + | − | Fam1, clade2 | PspC6.1 | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 475 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 476 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 477 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 525 | 6A | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 478 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1, 2, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 479 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 480 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | − | Fam1 | … | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 481 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 2 | + | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 482 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 2 | + | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 483 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 484 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1, 3 | + | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 485 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 1, 3 | + | − | Fam1 | … | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 486 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 487 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 488 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 489 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 490 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 491 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | PspC9.1 |

| BHN 492 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 493 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 494 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 495 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 496 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 497 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 498 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 499 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 500 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 501 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 502 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | Remnant | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 503 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 504 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 53 | 62 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 51 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 505 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 526 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 2 | + | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 528 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 529 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 530 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | − | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 531 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 532 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 533 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 2 | + | + | Fam2, clade 3 | … | … |

| BHN 534 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | … | … | … |

| BHN 535 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 536 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 506 | 6B | SWE6B-1 | 176 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 553 | 6B | SWE6B-4 | 553 | 553 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 554 | 6B | SWE6B-4 | 553 | 553 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 555 | 6B | SWE6B-4 | 553 | 553 | C | 2 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 556 | 6B | SWE6B-4 | 553 | 553 | C | 2 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 557 | 6B | SWE6B-4 | 553 | 553 | C | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 559 | 6B | SWE6B-5 | 553 | 553 | C | 1, 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 560 | 6B | SWE6B-5 | 553 | 553 | C | 1 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 320 | 6B | SWE6B-6 | 385 | 90 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 304 | 6B | SWE6B-7 | 315 | 315 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 302 | 6B | SWE6B-7 | 315 | 315 | I | − | − | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 272 | 6B | SWE6B-8 | 2659 | 90 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 255 | 6B | SWE6B-8 | 146 | 90 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 306 | 6B | SWE6B-9 | 2660 | 2660 | I | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 278 | 6B | SWE6B-10 | 90 | 90 | I | 1, 2 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 197 | 6B | SWE6B-11 | 138 | 138 | I | 2 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 507 | 6B | SWE6B-12 | 176 | 138 | C | 2, 3 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 514 | 6B | SWE6B-13 | 176 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 515 | 6B | SWE6B-14 | 8790 | Not present in any group | C | − | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 516 | 6B | SWE6B-15 | 2156 | 156 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 517 | 6B | SWE6B-16 | 8789 | Not present in any group | C | − | − | − | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 518 | 6B | SWE6B-17 | 8791 | Not present in any group | C | 2 | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 519 | 6B | SWE6B-18 | 553 | 553 | C | 2 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 520 | 6B | SWE6B-19 | NC | NC | C | Unclassified | + | − | … | … | … |

| BHN 521 | 6B | SWE6B-20 | 710 | 1121 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

| BHN 522 | 6B | SWE6B-21 | 2936 | Singleton | C | − | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 523 | 6B | SWE6B-22 | 176 | 138 | C | Unclassified | + | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 509 | 6B | SWE6B-23 | 176 | 138 | C | 2, 3 | − | + | Fam1 | … | … |

| BHN 508 | 6B | 18C-3 | 138 | 138 | C | 3 | + | + | Fam2 | … | … |

Abbreviations: CC, clonal complex; NC, nonconclusive; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; ST, sequence type; –, negative; +, positive.

a CCs are named after the predicted founder as of the 2008 Mars Project in the MLST database.

b Defined by a positive PCR product of primer pairs designed by Romero et al [16]. The term “unclassified” denotes a lysogenic strain but no detectable PCR product, suggesting the presents of a novel prophage not belonging to any of the 3 groups previously described by Romero et al [16]. The term “remnant” denotes expression of genes without lyse upon induction of mitomycin C.

c Determined by PCR, using specific primers.

d Determined by PCR, using specific primers, and clades by sequencing.

e Determined by Sanger sequencing. For pspC1, PspC6.9 was from G386, and PspC6.1 was from G31. For pspC2, PspC9.4 was from G386, and PspC9.1 was from G31.

f Selected for whole-genome sequencing.

Intraclonal Allelic Variations of Known Virulence Surface Proteins

The comparative sequence analyses revealed differences among the 4 CC138 isolates in genes encoding the important virulence-associated surface proteins pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA), pneumococcal choline-binding protein A (PcpA), and pneumococcal surface protein C (PspC). These surface proteins are known to represent dominating antigens to which many individuals without prior invasive disease have antibodies [23].

pspA is a mosaic gene that has evolved through extensive recombination and is an important vaccine candidate [18, 24]. PspA is required for pneumococcal virulence and contributes to colonization in mice, and it has been shown to interfere with the fixation of complement C3 [25, 26] and to bind human lactoferrin [27]. PspA can be divided into 3 families and 6 clades, in which the clade-defining region is determined by residues 192–290. It has previously been reported that a single clone usually consists of strains from 1 specific clade. However, in this study of CC138 isolates, we observed extensive intraclonal pspA variation (Table 2). Thus, BHN191 of SWE6B-3 possessed a pspA allele similar to TIGR4 (pspA family 2, clade 3), whereas the other 3 isolates carried a pspA allele similar to R6 (pspA family 1) but still with sequence differences placing them in different clades (Table 2).

All CC138 6B isolates were subsequently tested for the pspA family by use of family-specific primers, and the complete pspA gene was sequenced from a selected number of isolates to determine the clade (Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). All isolates from SWE6B-3 belonged to pspA family 2, and those sequenced were of clade 3. In SWE6B-2, only a minority of isolates possessed a pspA allele of family 1 (clade 1), whereas the majority were of pspA family 2 (clade 3). Finally, for SWE6B-1, most isolates carried pspA of family 1 (clade 2), but 2 were of family 2 (clades 2 and 5). Thus, for the largest single clone among children (CC138) in Stockholm, we identified extensive pspA variation. However, no specific pspA family and clade correlated to either carriage or disease.

Another sequence difference among the 4 completely sequenced CC138 strains was the complete absence of pcpA in the carrier isolates BHN427 of SWE6B-1 but the presence of this virulence-associated gene in the other 3 isolates (Table 2). In BHN427 pcpA was replaced by 2 open reading frames with no similarities to pcpA (data not shown). The presence of pcpA was further analyzed by PCR in all CC138 isolates (Table 2). The pcpA gene was absent in 10 of 72 tested isolates, of which 8 were from healthy carriers and 2 from individuals with invasive disease. PcpA is a potential vaccine candidate, but unlike PspA expression of this protein is not required for colonization in mice [28].

Each of the 4 CC138 isolates possessed 2 different pspC genes, pspC1, encoding a choline binding version of this highly variable protein, and pspC2, encoding a cell-wall-anchored LPXTG protein. Of the 4 completely sequenced CC138 isolates, BHN191 and BHN418 were of pspC1 variant PspC6.9. [29]. Nevertheless, the 2 predicted amino acid sequences differed at a number of locations (Supplementary Figure 1; the 2 sequences can be aligned with 80.9% sequence identity, with 4.0% gaps). The 2 pspC1 genes of BHN237 and BHN427 (both of SWE 6B-1) were, however, identical and of PspC6.1 [29]. All 4 pspC1 sequences contain 2 copies of an RNYPT motif known to bind human FH [29].

The 4 pspC2 sequences were all very similar but not identical. BHN191 and BHN418 both had a pspC2 allele of PspC9.4, and the sequences were identical except for the length of the proline-rich repeat region. BHN237 and BHN427, on the other hand, were of PspC9.1 and were 99.1% identical to each other, with all differences in the repeat region. When additional CC138 isolates were sequenced for pspC2 (Table 2), all SWE6B-3 and SWE6B-2 isolates had a PspC9.4 allele, and the SWE6B-1 isolates were all PspC9.1. The major difference again involved the number of repeats in the proline-rich region.

Intraclonal Variations Within PspC1 and PspC2 and Correlation to Human FH Binding

One human-specific virulence property in pneumococci is the ability to sequester human alternative pathway inhibitor FH, leading to evasion of complement-mediated opsonization. In pneumococci, only PspC1 and PspC2 (Hic) have been shown to bind FH [30, 31]. Since we could identify sequence variations in the different pspC1 and pspC2 genes of the 4 6B CC138 strains, we examined FH binding by use of Far Western blotting (Figure 2). FH was shown to bind 1 major protein in strainT4, corresponding in size (95 kDa) to PspC1 purified from this strain (data not shown). All 4 6B strains were shown to preferentially bind FH to a similarly sized protein as in strain T4, suggesting that it represents PspC1. Interestingly, we found that FH bound more intensively to this protein in invasive strain BHN191, compared with the other 3 strains. Since none of the 4 CC138 strains were possible to transform, we were unable to create mutants in the pspC1 or pspC2 genes. FH binding was further quantified by whole-cell ELISA, using strain T4 as the reference strain, in which pneumococci were attached to a microtiter plate and the binding of FH was analyzed. The 4 6B strains were found to sequester more FH than strain T4 (difference, 2–4-fold), with BHN191 exhibiting the highest degree of binding (data not shown), suggesting that enhanced complement resistance could be one explanation why this strain exhibited a higher invasiveness in children than the other isolates. All 4 strains bound FH with maintained cofactor activity, as representative C3b cleavage products were found when the strains were pretreated with FH and incubated with C3b and factor I (data not shown).

Differences in Virulence Within CC138 in an Experimental Mouse Model May Correlate With the Presence of Virulence Protein PcpA

The 4 CC138 isolates were next tested for virulence in an intranasal murine model. The carrier isolate BHN427 was considerably less virulent than the corresponding invasive isolate BHN237 (Figure 3A–C). It is likely that this difference in mice virulence reflects the lack of PcpA, a known mouse virulence determinant, in the carrier isolate. However, we found no difference in mouse virulence between invasive BHN191 of SWE6B-3 with high invasive-disease potential, compared with carrier BHN418 of SWE 6B-2 and invasive BHN237 of SWE6B-1, suggesting that the high invasive-disease potential of SWE6B-3 in children may represent 1 or more virulence attributes only operating in the human setting, such as sequestration of human FH.

Figure 3.

Survival of mice (A) and the number of colony-forming units (CFU) in the bloodstream at 24 hours (B) after intranasal challenge with the 4 strains of serotype 6B and clonal complex 138 representing clonal types with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns indicating different invasive-disease potentials. *P < .05.

Concluding Remarks

We found that efficient horizontal gene transfer events generate intraclonal variants in dominating lineages that differ in invasive-disease potential in children and in virulence in mice. Also, we observed major differences in phage DNA content and in the presence or sequence of surface antigens. These surface antigens are known to be important virulence factors, and some bind human FH, which has been shown to increase complement resistance and to promote invasion directly [29, 32, 33]. We found differential FH binding among intraclonal variants, potentially affecting invasiveness. We hypothesize that a constantly ongoing selection for immune escape variants of pneumococci occurs during carriage that result in variants that may affect the invasive-disease potential in children by simultaneously affecting the disease-promoting properties of individual proteins.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the clinical microbiology laboratory in Stockholm, for sending the pneumococcal isolates; and Ingrid Andersson, Christina Johansson, and Gunnel Möllerberg, for excellent technical assistance.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic research, the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg foundation, the EU commission DG research project Pneumopath, Marie Curie project EIMID-IAPP and by ALF-bidrag from the Stockholm City Council.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Nunes S, Sa-Leao R, Carrico J, et al. Trends in drug resistance, serotypes, and molecular types of Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizing preschool-age children attending day care centers in Lisbon, Portugal: a summary of 4 years of annual surveillance. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1285–93. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1285-1293.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henriqus Normark B, Christensson B, Sandgren A, et al. Clonal analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae nonsusceptible to penicillin at day-care centers with index cases, in a region with low incidence of resistance: emergence of an invasive type 35B clone among carriers. Microb Drug Resist. 2003;9:337–44. doi: 10.1089/107662903322762761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueggemann AB, Griffiths DT, Meats E, Peto T, Crook DW, Spratt BG. Clonal relationships between invasive and carriage Streptococcus pneumoniae and serotype- and clone-specific differences in invasive disease potential. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1424–32. doi: 10.1086/374624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandgren A, Sjostrom K, Olsson-Liljequist B, et al. Effect of clonal and serotype-specific properties on the invasive capacity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:785–96. doi: 10.1086/381686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjostrom K, Spindler C, Ortqvist A, et al. Clonal and capsular types decide whether pneumococci will act as a primary or opportunistic pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:451–9. doi: 10.1086/499242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blomberg C, Dagerhamn J, Dahlberg S, et al. Pattern of accessory regions and invasive disease potential in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1032–42. doi: 10.1086/597205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagerhamn J, Blomberg C, Browall S, Sjostrom K, Morfeldt E, Henriques-Normark B. Determination of accessory gene patterns predicts the same relatedness among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae as sequencing of housekeeping genes does and represents a novel approach in molecular epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:863–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01438-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjostrom K, Blomberg C, Fernebro J, et al. Clonal success of piliated penicillin nonsusceptible pneumococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12907–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705589104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright MC, Spratt BG. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 11):3049–60. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffey TJ, Enright MC, Daniels M, et al. Recombinational exchanges at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus lead to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:73–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermans PW, Sluijter M, Hoogenboezem T, Heersma H, van Belkum A, de Groot R. Comparative study of five different DNA fingerprint techniques for molecular typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1606–12. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1606-1612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://spneumoniae.mlst.net/ . Accessed 2008.

- 15.Feil EJ, Li BC, Aanensen DM, Hanage WP, Spratt BG. eBURST: inferring patterns of evolutionary descent among clusters of related bacterial genotypes from multilocus sequence typing data. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1518–30. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.5.1518-1530.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero P, Garcia E, Mitchell TJ. Development of a prophage typing system and analysis of prophage carriage in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1642–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02155-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iannelli F, Oggioni MR, Pozzi G. Allelic variation in the highly polymorphic locus pspC of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene. 2002;284:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00896-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollingshead SK, Becker R, Briles DE. Diversity of PspA: mosaic genes and evidence for past recombination in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5889–900. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5889-5900.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukashin AV, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver T, Berriman M, Tivey A, et al. Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2672–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giefing C, Meinke AL, Hanner M, et al. Discovery of a novel class of highly conserved vaccine antigens using genomic scale antigenic fingerprinting of pneumococcus with human antibodies. J Exp Med. 2008;205:117–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Paton JC, et al. Immunizations with pneumococcal surface protein A and pneumolysin are protective against pneumonia in a murine model of pulmonary infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:339–48. doi: 10.1086/376571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balachandran P, Brooks-Walter A, Virolainen-Julkunen A, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE. Role of pneumococcal surface protein C in nasopharyngeal carriage and pneumonia and its ability to elicit protection against carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2526–34. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2526-2534.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren B, McCrory MA, Pass C, et al. The virulence function of Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein A involves inhibition of complement activation and impairment of complement receptor-mediated protection. J Immunol. 2004;173:7506–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hakansson A, Roche H, Mirza S, McDaniel LS, Brooks-Walter A, Briles DE. Characterization of binding of human lactoferrin to pneumococcal surface protein A. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3372–81. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3372-3381.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glover DT, Hollingshead SK, Briles DE. Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein PcpA elicits protection against lung infection and fatal sepsis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2767–76. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01126-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammerschmidt S, Agarwal V, Kunert A, Haelbich S, Skerka C, Zipfel PF. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:5848–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dave S, Brooks-Walter A, Pangburn MK, McDaniel LS. PspC, a pneumococcal surface protein, binds human factor H. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3435–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3435-3437.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janulczyk R, Iannelli F, Sjoholm AG, Pozzi G, Bjorck L. Hic, a novel surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae that interferes with complement function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37257–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuste J, Khandavilli S, Ansari N, et al. The effects of PspC on complement-mediated immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae vary with strain background and capsular serotype. Infect Immun. 2010;78:283–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agarwal V, Asmat TM, Luo S, Jensch I, Zipfel PF, Hammerschmidt S. Complement regulator Factor H mediates a two-step uptake of Streptococcus pneumoniae by human cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23486–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.