Abstract

Aims/Introduction: Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) are major incretins that potentiate insulin secretion from pancreatic β‐cells. The factors responsible for incretin secretion have been reported in Caucasian subjects, but have not been thoroughly evaluated in Japanese subjects. We evaluated the factors associated with incretin secretion during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in Japanese subjects with normal glucose tolerance (NGT).

Materials and Methods: We measured plasma GIP and GLP‐1 levels during OGTT in 17 Japanese NGT subjects and evaluated the factors associated with GIP and GLP‐1 secretion using simple and multiple regression analyses.

Results: GIP secretion (AUC‐GIP) was positively associated with body mass index (P < 0.05), and area under the curve (AUC) of C‐peptide (P < 0.05) and glucagon (P < 0.01), whereas GLP‐1 secretion (AUC‐GLP‐1) was negatively associated with AUC of plasma glucose (P < 0.05). The insulinogenic index was most strongly associated with GIP secretion (P < 0.05); homeostasis model assessment β‐cell was the most the strongly associated factor in GLP‐1 secretion (P < 0.05) among the four indices of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity.

Conclusions: Several distinct factors might be associated with GIP and GLP‐1 secretion during OGTT in Japanese subjects. (J Diabetes Invest, doi: 10.1111/j.2040‐1124.2010.00078.x, 2011)

Keywords: Gastric inhibitory polypeptide, Glucagon‐like peptide‐1, Incretin

Introduction

Oral glucose administration leads to greater insulin release from pancreatic islets than intravenous glucose loading that yields equivalent glucose levels. Gut hormonal substances released in response to glucose include the incretins, gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1), which are responsible for 50–60% of postprandial insulin secretion1. GIP is secreted on meal ingestion from K‐cells in the proximal small intestine, whereas GLP‐1 is secreted from L‐cells in the distal small intestine and colon, and binds to their respective receptors (GIP receptor [GIPR] and GLP‐1 receptor) on the surface of pancreatic β‐cells to stimulate insulin secretion by increasing the intracellular adenosine 3′,5′‐monophosphate (cAMP) concentration2–4.

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by both decreased insulin secretion and reduced insulin sensitivity5–7. The incretin effect has been shown to be reduced in type 2 diabetic subjects compared with those with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) in previous studies8,9, suggesting that a reduced incretin effect might be associated with hyperglycemia after food intake and glucose loading in type 2 diabetes. When intravenous infusion of GIP or GLP‐1 was carried out in type 2 diabetic subjects, GLP‐1 potentiated insulin secretion from pancreatic β‐cells, but GIP did not, showing that the GIPR signal is downregulated in β‐cells in type 2 diabetes10. In studies using rodent models, it was reported that GIPR mRNA and protein expression levels in islets are decreased in the diabetic state11. In contrast, in the non‐diabetic obese state, GIP plays an important role in maintaining blood glucose levels12. The GIP signal might be enhanced as a result of increased GIPR sensitivity of β‐cells to GIP or increased GIP secretion from K‐cells in the non‐diabetic obese state. Indeed, GIP concentrations are reported to be increased in obese rodent models and human subjects compared with those in lean rodents and human subjects, respectively13–15. Furthermore, we have previously shown the hypersensitivity of GIPR to GIP in β‐cells of high fat‐induced obese mice16. Plasma GLP‐1 concentrations in type 2 diabetic patients are reported to be reduced after meal ingestion and glucose loading9,17. However, in other studies it was reported that GLP‐1 concentrations did not differ in NGT and type 2 diabetic subjects18–20. Thus, the measurement of GIP and GLP‐1 concentrations in various metabolic states is important to evaluate the effects of incretin on insulin secretion.

Insulin sensitivity in Asian subjects has been shown to be higher than in Mexican Americans and Caucasians in previous reports21,22, which is partly as a result of the fact that Asians, including Japanese, are generally less obese. Furthermore, insulin secretion rather than insulin sensitivity is the more important factor in progression from NGT to diabetes in Japanese subjects23. We have reported that early‐phase insulin secretion is considerably decreased, even in Japanese NGT subjects with 1‐h plasma glucose (PG) levels during oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of more than 180 mg/dL24. Thus, it is especially important to evaluate incretin secretion and determine the factors associated with incretin secretion in Japanese NGT subjects, because GIP and incretin is responsible for more than 50% of postprandial insulin secretion after glucose ingestion. The factors responsible for incretin secretion have been reported in Caucasian subjects, but have not been thoroughly elucidated in Japanese subjects.

In the present study, we evaluated GIP and GLP‐1 levels during OGTT and determined the factors involved in GIP and GLP‐1 secretion (area under the curve [AUC] of GIP and GLP‐1 during OGTT) in Japanese NGT subjects.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We recruited 17 Japanese healthy volunteers. The subjects had no history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia or kidney and liver diseases, and did not take any drugs 2 weeks before the study. The study was designed in compliance with the ethics regulations of the Helsinki Declaration and Kyoto University. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Study Procedure

The subjects’ age, height and bodyweight were determined. Blood samples for the measurement of liver and kidney function, HbA1c, serum triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL)‐cholesterol levels were drawn after an overnight fast. All subjects received OGTT. After the subjects fasted overnight for 10–16 h, standard OGTT with 75 g glucose was given according to the National Diabetes Data Group recommendations25. NGT was diagnosed according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria26.

Blood samples were collected at −15, 0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 min after glucose loading and were centrifuged at 1800 g at 4°C for 10 min. After collecting supernatant of the samples, plasma and serum were stocked at −80°C. Plasma GIP, GLP‐1 levels and the various parameters (PG, serum immunoreactive insulin [IRI], serum C‐peptide reactivity [CPR], TG, serum free fatty acid [FFA] and plasma glucagon) were measured at the indicated times (plasma GIP and GLP‐1 levels were measured at −15, 0, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min after glucose loading, and plasma glucagon levels were measured at −15, 0, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min after glucose loading). The PG levels were measured by glucose oxidase method. Serum IRI levels were measured by two‐site radioimmunoassay. Total GIP and total GLP‐1 levels were measured using human GIP ELISA kit (Linco Research, St Charles, MO, USA; range of detection from 8.2 pg/mL to 2000 pg/dL) and human GLP‐1 ELISA kit (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD, USA; range of detection from 2.4 pg/mL to 1,000,000 pg/dL), respectively, as previously described27,28. The AUC of PG, IRI, CPR, TG, FFA, glucagon, total GIP (AUC‐GIP) and total GLP‐1 (AUC‐GLP‐1) were calculated. We then analyzed the relationship between the AUC of GIP (GIP secretion) and GLP‐1 (GLP‐1 secretion) and age, body mass index (BMI) and the parameters during OGTT.

Statistical Analysis

Basal insulin secretion and sensitivity were evaluated by homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) β‐cell function and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR)29,30, respectively. Early‐phase insulin secretion and systemic insulin sensitivity during OGTT were evaluated by insulinogenic index31 and insulin sensitivity index (ISI) composite32. The calculations of the four indices were as follows:

|

All analyses were carried out using statistical analysis software (spss version 17.0, IBM, Somers, NY, USA) system. Statistical analysis was carried out by anova with Fisher’s PLSD test for changing levels of GIP, GLP‐1, and the parameters during OGTT and differences between the two groups were assessed by unpaired t‐test. We used simple regression analysis to determine the relationship between AUC‐GIP or AUC‐GLP‐1 and the age, BMI and the parameters during OGTT, and we carried out multiple regression analysis to determine the factors most strongly associated with AUC‐GIP and AUC‐GLP‐1, and the indices of insulin secretion and sensitivity. Probability (P) values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE).

Results

Table 1 shows clinical characteristics of the subjects. Mean age was 31.7 ± 1.3 years and mean BMI was 23.1 ± 0.9 kg/m2. No subjects had liver or kidney dysfunction. HbA1c, FPG, TG, total cholesterol and HDL‐cholesterol levels were within normal limits in the fasting state.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the subjects.

| n (male/female) | 17 (14/3) |

| Age (years) | 31.7 ± 1.3 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 0.9 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 25.2 ± 3.7 |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.7 ± 0.0 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.00 ± 0.31 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.56 ± 0.16 |

| HDL‐cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.51 ± 0.10 |

| Insulinogenic index | 66.22 ± 8.54 |

| HOMA β‐cell | 60.85 ± 8.89 |

| HOMA‐IR | 0.94 ± 0.15 |

| ISI composite | 11.45 ± 1.67 |

Means ± SE. HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HOMA, homeostasis model assessment; HOMA‐IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; ISI, insulin sensitivity index.

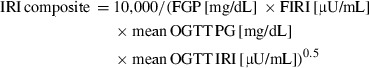

The levels of GIP, GLP‐1, PG, IRI, CPR, TG, FFA and glucagon after glucose loading were measured (Figure 1). The subjects were diagnosed NGT according to WHO criteria with fasting plasma glucose and 2‐h glucose levels below 6.1 and 7.8 mmol/L, respectively. Levels of PG, IRI and CPR were significantly increased from 10 min after glucose loading compared with fasting level (Figure 1a–c). FFA levels were significantly decreased from 10 min after glucose loading (Figure 1d). TG levels were not significantly changed during OGTT (Figure 1e). Glucagon levels were significantly decreased from 30 min after glucose loading (Figure 1f). Total GIP levels were significantly increased from 10 min during OGTT (Figure 1g). Total GLP‐1 levels were significantly increased from 10 min during OGTT with peaks at 30 and 120 min (Figure 1h).

Figure 1.

Concentrations of (a) plasma glucose, (b) serum immunoreactive insulin, (c) serum C‐peptide reactivity (CPR), (d) serum free fatty acid (FFA), (e) serum triglyceride (TG), (f) glucagon, (g) total gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and (h) total glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) during oral glucose tolerance test in 17 Japanese subjects. Mean ± SE, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs the levels at fasting.

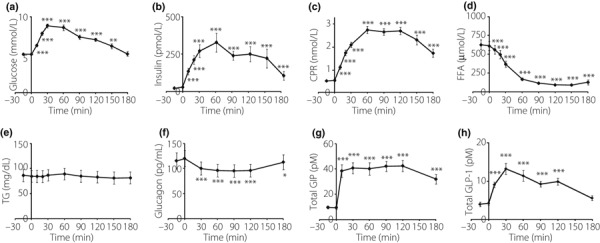

We analyzed the relationship between AUC‐GIP or AUC‐GLP‐1 and age, BMI and the several parameters (AUC of PG, IRI, CPR, TG, FFA and glucagon). AUC‐GIP were positively related to BMI and AUC of CPR, IRI and glucagon, but AUC‐GLP‐1 was not related to these factors (Figure 2a–c; AUC data of IRI during OGTT are not shown; P < 0.05). In contrast, AUC‐GLP‐1 was inversely related to AUC of PG (Figure 2d), but AUC‐GIP was not.

Figure 2.

Simple regression analysis of gastric inhibitory polypeptide secretion (AUC‐GIP) and (a) body mass index (BMI), (b) AUC of serum C‐peptide reactivity (CPR) and (c) glucagon. (d) Simple regression analysis of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 secretion (AUC‐GLP‐1) and AUC of plasma glucose (PG).

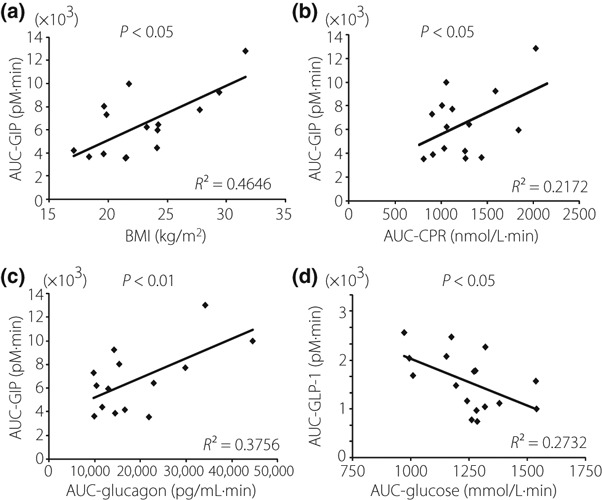

We then analyzed the relationship between AUC‐GIP or AUC‐GLP‐1 and indices of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity. AUC‐GIP was positively related to insulinogenic index and HOMA‐IR, whereas AUC‐GLP‐1 was positively related to HOMA β‐cell function (Figure 3a–c). ISI composite was not related to either AUC‐GIP or AUC‐GLP‐1 (Figure 3d). In addition, multiple regression analysis was carried out to determine the factors strongly associated with AUC‐GIP and AUC‐GLP. The insulinogenic index was the most strongly associated factor in AUC‐GIP (correlation coefficients 0.56, standardized β 0.56, P < 0.05) of the four indices; HOMA β‐cell function was the strongest factor in AUC‐GLP‐1 (HOMA β‐cell function: correlation coefficients 0.524, standardized β 0.870, P < 0.01, ISI composite: correlation coefficients 0.063, standardized β 0.581, P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Relationship between gastric inhibitory polypeptide secretion (AUC‐GIP) and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 secretion (AUC‐GLP‐1) and the indices of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity. (a) Insulinogenic index, (b) homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) β‐cell function, (c) homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR) and (d) insulin sensitivity index (ISI) composite. Ns, not significant.

Discussion

In the present study, we estimated the incretin level after glucose loading in Japanese NGT subjects and found that plasma GIP and GLP‐1 levels during OGTT are related to different factors.

Incretin action of GIP is reduced in the diabetic state as a result of decreased GIP receptor expression on pancreatic β‐cells11, whereas GIP signaling is enhanced and maintains glucose homeostasis by compensatory increased insulin secretion in the obese state15,16. In some human studies in Caucasians, plasma GIP levels are increased in obese subjects14,15 and there is a positive relationship between AUC‐GIP and AUC of FFA during OGTT18. In the present study, AUC‐GIP after glucose loading was not associated with AUC of FFA, but was positively associated with BMI, HOMA‐IR, and AUC of IRI and CPR after glucose loading. In fact, obese subjects are known to have hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance33,34, and BMI was strongly associated with AUC of IRI and CPR. Thus, GIP secretion from K‐cells may well be associated with insulin resistance to maintain postprandial hyperinsulinemia in Japanese NGT subjects. It is unknown why there was no correlation between AUC‐GIP and AUC‐glucose. It might be explained by the fact that GIP secretion is associated with the amount of glucose loading1, whereas blood glucose levels are maintained within normal levels by GIP‐induced compensatory insulin secretion in NGT subjects.

GLP‐1 secretions of type 2 diabetes subjects after glucose or meal ingestion are diverse in human studies9,17–19. Some studies report that GLP‐1 secretion is decreased in Caucasian type 2 diabetes9,17. Recently, it is reported that GLP‐1 levels after ingestion of glucose and mix meal in Japanese type 2 diabetic subjects were not decreased compared with those in NGT subjects, suggesting that GLP‐1 secretion is not decreased in Japanese type 2 diabetes20,35,36. Two studies of Caucasian subjects found that AUC‐GLP‐1 during OGTT is positively associated with age and AUC of glucagon, whereas AUC of GLP‐1 is negatively associated with BMI or bodyweight and AUC of FFA9,18. In the present study, AUC‐GLP‐1 was negatively related to AUC of PG during OGTT, showing that the increase in GLP‐1 secretion after glucose loading is associated with a decrease in postprandial glucose levels in Japanese NGT subjects. It has been reported that GLP‐1 levels after glucose loading are positively related to gastric empting in Caucasian subjects37. Although we did not measure gastric empting of the subjects in the present study, increasing GLP‐1 secretion after glucose loading might decrease postprandial glucose levels through gastric emptying. In the present study, BMI and AUC of FFA were not associated with AUC‐GLP‐1 during OGTT. Obese subjects have higher FFA levels than lean subjects38. However, because Japanese subjects are less obese than Caucasian subjects21, the difference observed in the relationship between AUC‐GIP and GLP‐1, and AUC of FFA might reflect this ethnic difference in Caucasians and Japanese.

Insulin secretion, rather than insulin sensitivity, is the more important factor in the progression from NGT to type 2 diabetes in Japanese patients23,39. Because incretin is an intestinal hormone that induces postprandial insulin secretion1, we hypothesize that GIP and GLP‐1 secretion is more crucial in Japanese subjects than in Caucasian subjects. Indeed, GLP‐1 mimetics and DPP‐4 inhibitors improve glycemic control better in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients than in Caucasian type 2 diabetic patients in clinical trials40–43. We therefore evaluated the correlation between GIP secretion (AUC‐GIP) and GLP‐1 secretion (AUC‐GLP‐1), and the indices of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in Japanese NGT subjects during OGTT. The values of HOMA β‐cell, insulinogenic index, HOMA‐IR and ISI composite were similar to those in previous studies of Japanese subjects24,30,39. AUC‐GIP was positively associated with the insulinogenic index and HOMA‐IR, and the insulinogenic index was strongly associated with AUC‐GIP, whereas AUC‐GLP‐1 was associated only with HOMA β‐cell among the four indices. It has been reported that early‐phase insulin secretion is an important factor in the progression from NGT through impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) to type 2 diabetes39, and that basal insulin secretion (HOMA β‐cell) and insulin resistance are important factors in the progression from NGT through impaired fasting glucose (IFG) to type 2 diabetes in Japanese patients44. Thus, enhancing the GIP and GLP‐1 signals might be particularly useful in inhibiting the progression of type 2 diabetes in Japanese patients. Recently, variants at the GIP receptor gene locus associated with 2‐h glucose levels during OGTT were identified by meta‐analysis of genome‐wide association studies45. In subjects who carry this GIP receptor risk allele, early‐phase insulin secretion is decreased. These data seem to support our results that GIP secretion is associated with insulinogenic index in Japanese NGT subjects.

In conclusion, we evaluated plasma GIP and GLP‐1 levels during OGTT in Japanese NGT subjects. GLP‐1 secretion was associated with PG during OGTT, and basal insulin secretion (HOMA β‐cell) and GIP secretion was associated with BMI and early‐phase insulin secretion (insulinogenic index). Thus, there might be different factors associated with GIP and GLP‐1 secretion during OGTT in Japanese subjects.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Yutaka Seino (Kansai Electric Power Hospital) for his helpful suggestions. This study was supported by Scientific Research Grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and by Kyoto University Global COE Program ‘Center for Frontier Medicine’, and also by Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd.

References

- 1.Nauck MA, Homberger E, Siegel EG, et al. Incretin effects of increasing glucose loads in man calculated from venous insulin and C‐peptide responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986; 63: 492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seino Y, Fukushima M, Yabe D. GIP and GLP‐1, the two incretin hormone: similalities and differernce. J Diabetes Invest 2010; 1: 8–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab 2010; 3: 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon‐like peptide 1. Physiol Rev 2007; 87: 1409–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitrakou A, Kelley D, Mokan M, et al. Role of reduced suppression of glucose production and diminished early insulin release in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 1992; 2: 22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, et al. Increased insulin concentrations in nondiabetic offspring of diabetic parents. N Engl J Med 1988; 17: 1297–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saad MF, Knowler WC, Pettitt D, et al. A two‐step model for development of non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes. Am J Med 1991; 90: 229–235 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauck M, Stöckmann F, Ebert R, et al. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 1986; 29: 46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muscelli E, Mari A, Casolaro A, et al. Separate impact of obesity and glucose tolerance on the incretin effect in normal subjects and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2008; 57: 1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, et al. Preserved incretin activity of glucagon‐like peptide 1 [7‐36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type‐2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1993; 91: 301–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holst JJ, Gromada J, Nauck MA. The pathogenesis of NIDDM involves a defective expression of the GIP receptor. Diabetologia 1997; 40: 984–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Yano H, et al. Glucose intolerance caused by a defect in the entero‐insular axis: a study in gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 14843–14847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, et al. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat Med 2002; 8: 738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flatt PR, Bailey CJ, Kwasowski P, et al. Abnormalities of GIP in spontaneous syndromes of obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 1983; 32: 433–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creuzfeldt W, Ebert R, Willms B, et al. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and insulin in obesity: increased response to stimulation and defective feedback control of serum levels. Diabetologia 1978; 14: 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada N, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, et al. A novel GIP receptor splice variant influences GIP sensitivity of pancreatic beta‐cells in obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E61–E68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilsbøll T, Krarup T, Deacon CF, et al. Reduced postprandial concentrations of intact biologically active glucagon‐like peptide 1 in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2001; 50: 609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vollmer K, Holst JJ, Baller B, et al. Predictors of incretin concentrations in subjects with normal, impaired, and diabetic glucose tolerance. Diabetes 2008; 57: 678–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faerch K, Vaag A, Holst JJ, et al. Impaired fasting glycaemia vs impaired glucose tolerance: similar impairment of pancreatic alpha and beta cell function but differential roles of incretin hormones and insulin action. Diabetologia 2008; 51: 853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabe D, Kuroe A, Lee S, et al. Little enhancement of meal‐induced glucagon‐like peptide 1 secretion in Japanese: comparison of type 2 diabetes patients and healthy controls. J Diabetes Invest 2010; 1: 56–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu KC, Chuang LM, Yoon C. Comparison of measured and estimated indices of insulin sensitivity and beta cell function: impact of ethnicity on insulin sensitivity and beta cell function in glucose‐tolerant and normotensive subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 1620–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandavilli A, Cyranoski D. Asian’s big problem. Nature Med 2004; 10: 325–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seino Y, Ikeda M, Yawata M, et al. The insulinogenic index in secondary diabetes. Horm Metab Res 1975; 7: 323–335 1150131 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harada N, Fukushima M, Toyoda K, et al. Factors responsible for elevation of one hour postchallenge plasma glucose levels in Japanese men. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008; 81: 284–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Diabetes Data Group . Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 1979; 28: 1039–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberi KG, Zimmeret PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998; 54: 539–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narita T, Katsuura Y, Sato T, et al. Miglitol induces prolonged and enhanced glucagon‐like peptide‐1 and reduced gastric inhibitory polypeptide responses after ingestion of a mixed meal in Japanese Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 187–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim GE, Huang GJ, Flora N, et al. Insulin regulates glucagon‐like peptide‐1 secretion from the enteroendocrine L cell. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 580–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β‐cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985; 28: 412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukushima M, Taniguchi A, Sakai M, et al. Homeostasis model assessment as a clinical index of insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1911–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda M, Defronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euroglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seltzer HS, Allen EW, Herron AL Jr, et al. Insulin secretion in response to glycemic stimulus: relation of delayed initial release to carbohydrate intolerance in mild diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1967; 46: 323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rabinowitz D, Zierler KL. Forearm metabolism in obesity and its response to intra‐arterial insulin. Characterization of insulin resistance and evidence for adaptive hyperinsulinism. J Clin Invest 1962; 41: 2173–2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 1991; 14: 173–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kozawa J, Okita K, Imagawa A, et al. Similar incretin secretion in obese and non‐obese Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 393: 410–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Yabe D, Nohtomi K, et al. Intact glucagon‐like peptide‐1 levels are not decreased in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J 2009; 57: 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wishart JM, Horowitz M, Morris HA, et al. Relation between gastric empting of glucose and plasma concentrations of glucagon‐like peptide‐1. Peptides 1998; 19: 1049–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson CM, et al. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J Clin Invest 2004; 113: 1582–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki H, Fukushima M, Usami M, et al. Factors responsible for development from normal glucose tolerance to isolated postchallenge hyperglycemia. Diabetes care 2003; 26: 1211–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madsbad S, Schmitz O, Ranstam J, et al. Improved glycemic control with no weight increase in patients with type 2 diabetes after once‐daily treatment with the long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide 1 analog liraglutide (NN2211): a 12‐week, double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1335–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aschner P, Kipnes MS, Lunceford JK, et al. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2632–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seino Y, Rasmussen MF, Zdravkovic M, et al. Dose‐dependent improvement in glycemia with once‐daily liraglutide without hypoglycemia or weight gain: a double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008; 81: 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nonaka K, Kakikawa T, Sato A, et al. Efficacy and safety of sitagliptin monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007; 79: 291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitsui R, Fukushima M, Nishi Y, et al. Factors responsible for deteriorating glucose tolerance in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes in Japanese men. Metabolism 2006; 55: 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saxena R, Hivert M, Langenberg C, et al. Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 142–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]