Abstract

Generating gene and cell therapy products under good manufacturing practices is a complex process. When determining the cost of these products, researchers must consider the large number of supplies used for manufacturing and the personnel and facility costs to generate vector and maintain a cleanroom facility. To facilitate cost estimates, the Indiana University Vector Production Facility teamed with the Indiana University Kelley School of Business to develop a costing tool that, in turn, provides pricing. The tool is designed in Microsoft Excel and is customizable to meet the needs of other core facilities. It is available from the National Gene Vector Biorepository. The tool allows cost determinations using three different costing methods and was developed in an effort to meet the A21 circular requirements for U.S. core facilities performing work for federally funded projects. The costing tool analysis reveals that the cost of vector production does not have a linear relationship with batch size. For example, increasing the production from 9 to18 liters of a retroviral vector product increases total costs a modest 1.2-fold rather than doubling in total cost. The analysis discussed in this article will help core facilities and investigators plan a cost-effective strategy for gene and cell therapy production.

Boeke and colleagues develop a costing tool for the generation of gene and cell therapy products under good manufacturing practices. The tool, which is available from the National Gene Vector Biorepository, was designed in Microsoft Excel and is customizable to any vector production core facility. The tool contains three different costing methods and was developed in an effort to meet the A21 circular requirements for U.S. core facilities performing work for federally funded projects.

Introduction

Recent successes in gene therapy clinical trials for genetic diseases such as adenosine deaminase deficiency, adrenoleukodystrophy, Leber congenital amaurosis, and hemophilia have energized the field (Bainbridge et al., 2008; Maguire et al., 2008; Aiuti et al., 2009; Cartier et al., 2009; Nathwani et al., 2011). Moreover, encouraging results in melanoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia provide proof of principle that the technology has potential for cancer and other diseases beyond those caused by monogenic mutations (Morgan et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2011). At the present time, gene therapies differ from traditional pharmaceutical agents in that many of these products are manufactured in academic production facilities. The reason for this is multifactorial. Large pharmaceutical companies are just now exploring the potential of gene therapy, and most current products are still in early phase clinical trials. Also, the production of viral vectors is a unique science that has generally been developed within the academic community.

When clinical products are generated in an academic core receiving funds from the U.S. government, special consideration must be taken when setting the cost of core services. Specifically, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget A21 Circular—“Principles for Determining Costs Applicable to Grants, Contracts, and Other Agreements with Educational Institution”—mandates that the price of a core service must represent the actual cost of delivering the service for institutions charging a facilities and administrative costs fee (commonly referred to as “indirect” costs) (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2012). To comply with the mandate, cores must carefully assess their operating costs and develop a fee structure that represents these costs. For manufacturing gene therapy products in a good manufacturing practices (GMP) environment, the determination of actual costs is complex. Personnel time includes hands-on work with a specific product, but time spent in facility maintenance and training must be taken into account as well. Cost calculations are further complicated if investigators are requesting core services in a grant application since the grant may not be funded for one or more years from the time the estimate is provided. Therefore, accurately estimating the cost of core services is important in maintaining the financial viability of a core and is also a key compliance issue.

In an effort to facilitate cost determination, the Indiana University Vector Production Facility (IU VPF) directors participated in a core improvement program offered through the Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute. The program teamed masters of business administration faculty and students from the Indiana University Kelley School of Business with IU VPF staff. The students participated in a semester-long elective, meeting weekly with IU VPF core personnel, assessing workflow and developing an Excel-based tool to determine production costs. This article describes the development of the tool and its utility in capturing cost inputs for viral vector production and determining total costs for each production run. The costing tool can be adapted to any core facility, and the illustrative example provided for vector production can assist investigators seeking clinical-grade material in understanding the influence of batch size on vector cost. The tool is currently available free of charge on the National Gene Vector Biorepository website (www.NGVBCC.org).

Methods

Data collection

The list of supplies used in calculating costs was obtained by recording items used in retroviral vector production at the time the item entered the production suite. This process was repeated two to three times for each manufacturing activity, and the average number of items used was entered into the costing tool. Quantities of disposable items for daily, monthly, semi-annual, and annual maintenance were derived from the corresponding cleanroom operations and maintenance standard operating procedures (SOP). Item prices are approximations based on online catalog prices or invoice documents. Reagent shipping costs were estimated by dividing the annual shipping costs charged to the IU VPF by the number of production runs per year. The cost of shipping the final product represents the actual cost of shipping using an overnight courier.

As stated above, the costing tool does not include the facility and administrative (F&A) costs fee recovered by Indiana University. Utilities, building maintenance, major repairs, and human resources management are not included in our analysis as they are covered by our institution through the F&A fees. Our facility was partially funded through an NIH construction grant that stipulated depreciation could not be included in fees charged to federally funded projects. The tool does allow the user to include these costs, if appropriate.

Costing tool methods

The costing tool was developed as a Microsoft Excel workbook to facilitate ease of use given the general availability and experience with this program. The tool is prepopulated with a mock analysis of a vector production as a means of illustration but is intended to be modified to meet the user's need. After opening the workbook, the user will find instructions by clicking on the Instructions tab. Throughout the workbook, the values in the colored cells can be modified by the user to capture the specific campaign requirements. Cells in white are locked to protect the cost calculation formulae. The Summary tab provides a data summary and cost determinations of three different batch sizes for each of the three costing models.

At the top of this worksheet, the user can enter up to three different batch sizes to be analyzed and also change the number of campaigns predicted per year, the number of days the facility will be in operation (i.e., not including shut-down periods), and the estimated failure rate. This tab also requests an estimate of the “Production Duration in Day,” which is used in the day rate model. As the Campaign model does not consider the number of days in estimating costs, the tool does allow the user to increase the charge for personnel and facility if the campaign will require greater effort and facility use by using the “Batch Size Multiplier” on the top right of the worksheet (the standard batch size is assigned a value of 1). Once the colored cells under the Summary tab are populated by the user, the tool then displays the total cost per batch and the cost per liter graphically and numerically.

The data presented under the Summary tab is drawn from the Supply, Personnel, and Facility tabs. The Supply tab contains the list of reagents and unit prices by batch size and is broken down by production phase. The spreadsheet columns are not protected, so the user can alter cost inputs to match their process. As discussed above, supply costs are allocated to the phase during which the supply item is consumed. The Personnel tab lists all employees involved in production activities. Personnel are categorized into technical staff, quality assurance, and management. Each individual is identified on the left column with their annual salary. At our institution, the benefits (fringe) rate differs for biweekly employees and professional staff, and the model accounts for this difference. A column also calculates salary costs based on annual percent effort expended by the employee on production activities. The Facility tab captures the cost of clean-room cleaning and maintenance activities along with the cost of service contracts, equipment recertification, and calibrations. The costs listed are annual costs. Users may add or delete items under this tab in order to customize the tool to meet the needs of their facility. The Service Expenses tab allows the user to list equipment and other items that incur an annual service contract or maintenance cost; the sum of these costs is then directly entered into the facility costs. While we currently do not utilize depreciation of equipment in our estimate, the Service Expenses tab allows the user to track these costs as well.

There are also nine tabs representing each of the three models with the three different batch sizes. Data from the respective cost estimate is then used to derive the data provided in the Summary page. Cells within these nine tabs should not be altered.

Results

Description of the IU VPF

The costing tool was developed for the IU VPF, which is dedicated to the production of Phase I/II gene therapy products and is organized into three areas: vector production, vector certification, and administration of the National Gene Vector Biorepository (Cornetta et al., 2005). The tool presented here was designed to address the production efforts. The production team consists of a Ph.D.-level supervisor and two full-time production technicians. The IU VPF has a dedicated quality assurance specialist who divides their time between production and certification efforts. The facility is managed by a faculty level Director and Associate Director. To date, the IU VPF facility has focused on retroviral vectors generated using stable packaging cell lines, and lentiviral vector products generated by transient transfection in HEK293T cell lines. It is located within the IU School of Medicine in Indianapolis and construction was funded, in part, by an NIH Construction Grant (NCRR C06-RR020128).

Costing tool design

In designing the costing tool, the team reviewed the production process and identified four specific phases: preparation, cell expansion, harvest, and change-over (Fig. 1). The preparation phase involves ordering supplies, sequencing of plasmids, preproduction runs to document functionality of plasmids, media preparation, and assembly of disposables including filtration units. Much of the preparation work is performed outside the cleanroom, although media preparation requires approximately one week of cleanroom time. The cell expansion phase requires approximately 2 weeks of cleanroom time and begins once a vial of Master Cell Bank cells is opened until the time sufficient cells are available to seed the harvest vessels. The harvest phase (from introduction of cells to the final harvest vessel through filtration, purification, concentration, and vialing), generally takes one week of cleanroom time. Change-over is the cleaning and revalidation process that occurs in preparation for the next production and requires approximately one week of cleanroom time.

FIG. 1.

Vector manufacturing phases and categories of expenses. The figure depicts four phases of vector manufacturing and the three categories of expenses used in generating a costing model. Gray boxes represent costs that are similar for most vector production and can be standardized in estimating vector costs. Harvest costs (diagonal lined boxes) reflect differences in processing and volume difference in production and require customized cost estimates for each product.

The team also identified three major categories of costs associated with production: supplies, personnel, and facility costs. It was decided to assign the cost of a specific supply item to the phase in which the item would be used (i.e., cell expansion, harvest, or change-over phase). As the majority of supply costs are associated with the harvest phase, and the harvest phase is generally vector specific, this stage of production requires customization for each vector product (Fig. 1). When evaluating our manufacturing process, we noted the supplies used in the cell expansion and change-over phases are similar so these costs do not require customization for most projects (represented in Fig. 1 as fixed cost for these phases of production). While standardize supply costs for all but the harvest phase worked for our facility, the tool does allow customization of all phases, if appropriate to the user's needs.

Estimating personnel costs is a major challenge of vector costing. Over a one-year period, the actual time an IU VPF technician spends in a production room is small compared to the effort spent in preparation and facility maintenance. Various cleaning and maintenance activities occur on a daily, weekly, monthly, semi-annual, or annual basis. Supplies for cleanroom operation and productions must be ordered, recorded for QA approval, and stored. Ongoing training is also important to meet Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements. In short, technical staff multitask a myriad of functions required for operating a cleanroom under GMP, and a large percentage of their effort will occur regardless of production activities. Therefore, a key element in tool design was how to allocate personnel costs to each production run.

In determining facility costs, a number of factors were considered during tool development. The first consideration was allocating cost for FDA-required semi-annual cleaning and recertification of critical equipment such as biological safety cabinets and facility heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. This process occupies approximately 8 weeks of facility time and is scheduled in December and June to accommodate staff vacation time. During cleaning and recertification (i.e., “shut-down”), the facility is not available for production yet personnel costs continue to accrue and significant costs are encumbered in the process of facility recertification. A second consideration was the general operation costs. For example, cleaning and environmental monitoring in common areas of the facility must occur regardless of work performed in a production room.

Allocating personnel and facility costs

The Costing Tool provides users with three approaches to determining production costs (Fig. 2): the Campaign, Day Rate, and Hybrid models. Each model uses the actual cost of supplies, but the models differ in how they allocate personnel and facility costs to individual production runs. The user can use the tool to compare the financial implications of each model and then select the most appropriate method for their facility. As will be illustrated in the simulation discussed below, how the personnel and facility costs are allocated is the key factor in determining the cost of production and assessing the risk that core revenue will not meet expenses.

FIG. 2.

Three options for cost analysis. The methods for generating cost estimates are depicted for the three pricing models available in the cost tool.

The Campaign model assumes each production is of similar duration and requires similar amounts of personnel and facility time (Fig. 2). It divides the annual personnel and facility costs by the estimated number of annual productions. In contrast, the Day Rate Costing model calculates a day use rate and calculates the personnel and facility charge based on the duration (in days) of a given production run. To determine the daily use rate, the annual personnel and facility costs are divided by the number of days the facility is in operation each year. For the facility, it is estimated that the shut-down period for cleaning and recertification occupy 61 days per year, leaving 304 operating days for vector production. The personnel and facility costs are then divided by 304 to arrive at the day use rate. To determine the personnel and facility cost for a production run, the duration of the production run (typically 35 days for the preparation, cell expansion, harvest, and change-over phases) are multiplied by the day use rate to obtain the personnel and facility cost for a specific production run.

The Hybrid model has components of the Campaign and Day Rate models. It divides the costs associated with the shut-down cleaning and recertification equally among all production runs but allocates the remaining personnel and facility costs based on days in production (Fig. 2). Specifically, this model first determines what percentage of time the facility is down for recertification (e.g., 61/365 days) then multiplies the total annual personnel and facility costs by this percentage (17%). The shut-down cost is then divided by the estimated number of production runs per year that become a fixed cost for a production (regardless of the number of days the product requires). The remaining 83% of the personnel and facility costs are then used to develop a daily use rate that is then multiplied by the number of days in production.

The tool has other features located in the Summary tab that allow for further customization. First, up to three different batch sizes can be entered into the model so that a side-by-side comparison can be performed. Second, the production run duration (in days) can be altered in the Day Rate and Hybrid models to reflect the time required for a specific batch size. Third, while the Campaign model assumes the length of each production run is equal, the Batch Size Multiplier allows users to make relative adjustments in personnel and facility costs for different batch sizes. Fourth, a “Failure Rate” can be entered on the Summary tab to build reserve funds in case of production failure. For illustrative purposes, we entered a failure rate of 10%, and the tool then increased the final vector cost by 10%. As these additional funds accrue, it provides the core with resources to repeat a failed production at no additional cost to the investigator.

Using the tool for simulating product costing

To illustrate how costing methods can alter price and risk, we populated the tool with the cost of production for three different batch sizes of a retroviral vector (9, 18, and 27 liters). As shown in Figure 3, the estimate for the days of clean-room use for the 9, 18, and 27 liters productions are 34, 35, and 37 days, respectively. These numbers were used in the Day Rate and Hybrid model. To illustrate the Batch Size Multipliers in the Campaign model, we utilized 1.0, 1.1, and 1.2 for the 9-, 18-, and 27-liter size, respectively. The annual days of operation was set at 304. As Figure 3 illustrates, the tool provides a quantitative cost analysis and graphical illustration of the cost per batch and cost per liter as determined by each of the three methods. The example in Figure 3 assumes eight production runs each year. At this rate, the Campaign model realizes the highest production cost per batch and the Day Rate model realizes the lowest production costs per batch.

FIG. 3.

Costing tool graphics. The figure represents the numeric (A) and graphic (B) information provided on the Summary tab of the costing tool for a theoretical retroviral vector production. The three batch sizes represent 9-, 18-, and 27-liter productions with the top panel demonstrating the total vector production cost and the bottom panel illustrating the per liter cost estimated using the Campaign (white), Day Use (black), and Hybrid (gray) models.

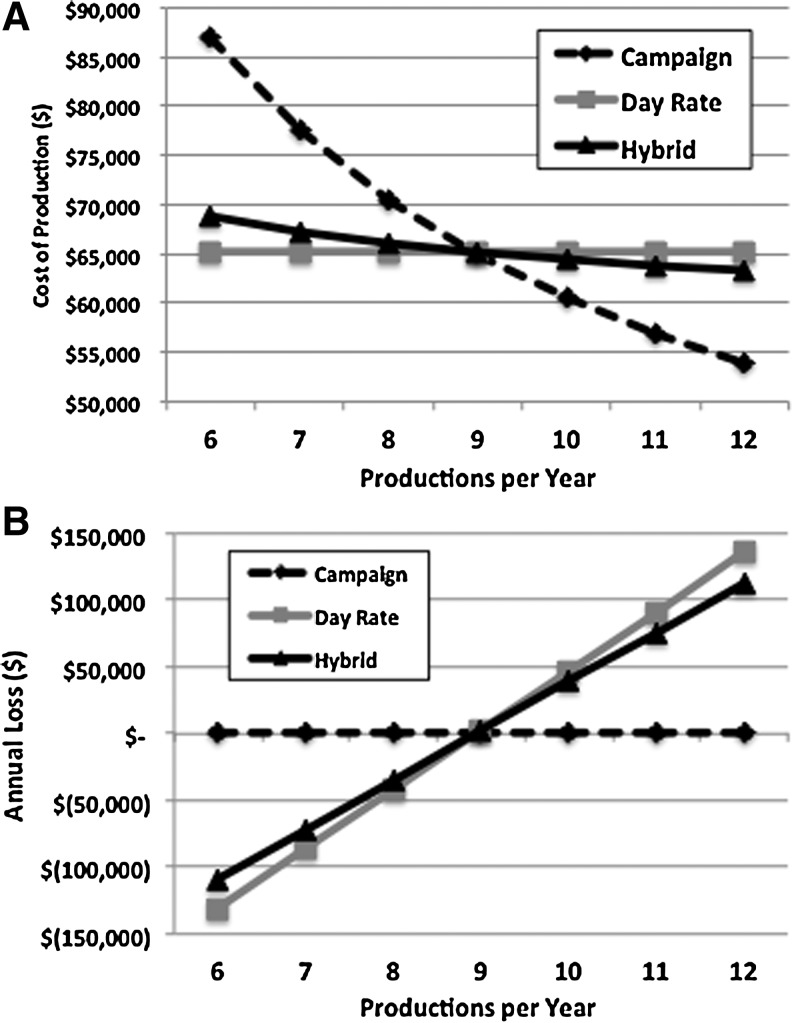

Figure 4A illustrates the cost of an 18-liter production as a function of the estimated production runs performed in a year. The Day Rate divides the annual personnel and facility costs by the number of days in operation (set here at 304 days). The Day Rate use will be the most cost competitive, but the disadvantage is noted in Figure 4B; if the facility is not running 304 days per year, the program will lose revenue. In this simulation, we see nine production runs are required per year (35 days per production run × 9 productions per year=315) to meet or exceed the 304-day requirement. Figure 4A also illustrates that the cost per production estimated in the Campaign model is the highest because the Campaign model allocates all of the annual personnel and facility costs to the productions. This means that if the number of products is significantly below capacity, the cost is passed on to the users so the financial risk to the facility is minimized (Fig. 4B). The Hybrid model shares the cost of the shut-down equally among all productions but uses a day rate for the actual production activity, resulting in a cost estimate (and risk) between the other two models. In this simulation, the Hybrid model did mitigate some of the loss when the facility is not used to maximal capacity (i.e., less than nine production runs per year), but the overall difference from the Day Rate use was small.

FIG. 4.

Cost analysis based on production activity. The figure represents a cost analysis for manufacturing a retroviral vector as a function of annual vector products generated assuming fixed supplies and annual personnel and facility costs and an average production time of 34 days. (A) The price per vector manufacturing was estimated using the three costing models based on the number of vectors generated annually. (B) The annual loss or gain of revenue based on the number of vectors generated annually.

Figure 4B also illustrates that if production activities are significantly above those predicted (assuming the facility has two production suites that allows simultaneous activities), the Day Rate and Hybrid model would result in net revenue that exceeds expenses and would not be in compliance with A21 requirements to match income and expenses. In this case, the user may wish to treat each production suite independently and divide personnel and facility costs accordingly. Also, the simulations assume a constant level of staffing; significant increases in manufacturing activities would require additional staff to compensate for the increased workload. If one hopes to maintain the current price but increase activity, the model allows one to see the financial impact of hiring additional staff and can be used to identify the number of production runs required to offset the cost of additional personnel.

In addition to comparing annual revenue and costs, the simulation facilitated a comparison of three batch sizes, thus allowing core personnel to provide options to investigators seeking vector production. As shown in Figure 5, the cost of a production run is not linear with the batch size. With the facility performing nine productions per year and using the Campaign costing model, doubling the batch size from 9 to 18 liters only increases the cost by a factor of 1.2. Tripling the batch size to 27 liters only increases the cost of production by a factor of 1.4. This occurs primarily because cells used in vector production double every 24 hr, so increasing from 9 to 18 liters generally requires one to two additional days in a 5-week production period. Hence, even a doubling of batch size does not significantly impact facility and personnel costs, so the additional costs generally reflect the differences in supply costs. The impact is also illustrated in the marked decrease in the cost per liter as large batches are produced (Fig. 3B). Similar savings were noted in the Day Rate and Hybrid models (Figs. 3B and 5).

FIG. 5.

Cost of vector production. The cost of vector production based on volume of material generated is illustrated for the three different costing models and an annual production of nine vectors per year. Numbers located above the columns for 18 and 27 liters represent the cost multiplier for the 9-liter costs.

Discussion

The recent successes in gene and cell therapies suggest that academic production sites can anticipate increasing demand for vectors. Determining the cost associated with each product is both complicated and time consuming and led the IU VPF to partner with faculty and MBA students from the IU Kelley School of Business to design a costing tool. The tool has allowed us to accurately capture costs and is easily adapted to estimate the cost of new products. Understanding the costs involved with production, and the nonlinear relationship between batch size and cost, can be helpful for investigators purchasing GMP-grade materials.

Many academic production facilities operate as cores and receive significant portions of their funding from NIH and other federal programs. Operating large core facilities presents special challenges, and business practices developed for commercial facilities must be adapted to the academic environment (Haley, 2009; Farber and Weiss, 2011) One significant challenge for U.S. facilities is the federal regulations that outline expectations for pricing services (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2012) Specifically, federal grants and contracts generally contain two components, the “direct” cost for the service and a facilities and administrative costs (“indirect”) fee that is federally negotiated for each institution. The regulations state the direct cost should reflect the actual cost for supplies and core operations (i.e., annual personnel and facility costs). The NIH has recognized that accurately determining the direct cost for core services and meeting the requirements of the federal law can be challenging and has published a draft document to explain costing issues for core facilities that fall under A21 Circular requirements (National Institutes of Health, 2010); a final document is anticipated to be published in the spring of 2013.

The tool presented in this article can help identify costs and assist in compliance with these challenging regulations. The tool illustrates that the personnel and facility costs for operating a GMP cleanroom is the major contributor to vector pricing. Different costing models proved very useful in setting annual production goals. The Campaign model ensures that operating cost equals revenue, but if the production goals are low, the cost per vector is high and the facility will not be cost-competitive. The Day Rate model illustrates the lowest cost for a product (i.e., the most favorable price for the consumer), but if the facility is not used to maximum capacity, the core will experience significant shortfall in revenue. Therefore, the tool can help guide efforts to reduce costs and limit financial risk when estimating vector prices for federal grants and contracts. As noted, the example provided excludes costs for building maintenance, utilities, or mark-ups because these costs are expected to be covered by the facilities and administrative costs (“indirects”) that accompany federal grants and contracts (although the tool allows these costs to be included if appropriate to the user's facility).

The nuances of meeting the expectations of the A21 circular can be challenging, and financial review by an institutional official from the institution's administrative office can assist core directors in setting core prices that are in compliance with the complex federal regulations. It should be noted that this model is specific for academic institutions in the United States generating work covered by federal grants; institutions are free to set prices above costs for nongovernment work (i.e., commercial activities). Commercial facilities and those outside the United States may not be required to set prices specifically at cost, but the model can still be of use to derive costs prior to setting prices.

The Campaign costing method is based on “process costing” principles typical in traditional manufacturing environments. The theory behind process costing is that overhead, such as facility equipment and managerial input, will be allocated across the span of all products manufactured within the year, thus averaging out the cost of equipment over all products it produced (Horngren, 1967). This structure of cost allocation provides the least amount of risk when working with funded research grants that require completing a quota of projects with similar duration and effort to be completed throughout a given year. The Day Rate model provides an alternative that emphasizes cost-effective pricing according to activity-based costing (ABC) principles (Cooper and Kaplan, 1992; Anderson and Kaplan, 2004) but does involve more risk. This risk can be minimized if the future production schedule was completely known, days the facility operates was unchanging, the facility dealt with no interruptions moving from one project to the next, and there was never a wait time moving from one production to the next. Unfortunately, the determination and accuracy of “Active Days in Lab” for production run, “Production Duration in Days for Different Batch Sizes,” and “% Effort” for all personnel can be challenging for academic production facilities. The challenge relates, in part, to the reliance on clients to provide necessary materials (e.g., vector plasmids used in production) in a timely fashion. Moreover, both academic and commercial clients often face funding issues that can challenge the facility to maintain a set schedule of activities beyond a few months time. Therefore, the Campaign model does offer an advantage to facilities that have a great variance in the predictability and demand for production services.

The Hybrid model is one that combines both Campaign and Day Rate approaches. This costing method mixes both a process and an ABC costing approach. The reasoning for this method was based on “down time” or recertification efforts that are required for regulatory compliance. While differing batch sizes utilize the “active lab time” at varying ABC rates, the recertification requirement to maintain GMP standards for each campaign is the same for all products regardless of size and duration. Thus, a fixed GMP overhead cost based on the number of Campaigns from the recertification delineation could be applicable as an implied and averaged fixed cost, as all campaigns benefit equally. The Hybrid model allows for competitive pricing but also provides a modest level of loss protection. Users of the tool can weigh each model and balance competitive pricing with financial risk while also using the spreadsheet for benchmarking efforts.

The costing tool illustrates how biomedical researchers can benefit from collaborations outside of the scientific community. Engaging with MBA students for this project provided valuable insights into cost methodology. The students educated core personnel on activity-based costing. The students gained insight into operations within a university cost center, as well as exposure to biotechnology research and GMP operations. While the simulation shown here reflects activities in a vector production core, the organization of the tool is suitable for cell-processing laboratories, sequencing facilities, or any cores with significant overhead expenses related to personnel or facility activities. Importantly, the tool can help quickly assess the cost of different production batches and facilitate estimates for clients. This simulation also provides investigators with insight into the major cost factors associated with vector production and can help them develop a cost-effective approach to identifying batch sizes for their research and clinical needs.

Acknowledgments

The MBA–student operations management consulting program is supported by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute grant (UL1 TR000006) from the NIH. The IU VPF is funded as the lentiviral vector production site from the NHLBI Gene Therapy Resource Program (HHSN2680001) and the NHLBI National Gene Vector Biorepository (P40HL11621).

Author Disclosure Statement

K.C. is founder of Rimedion, Inc., but is not employed by the company; there is no conflict of interest with the company activities and the development of this costing tool. The remaining coauthors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Aiuti A. Cattaneo F. Galimberti S., et al. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. New Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S.R. Kaplan R.S. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harvard Business Review. 2004;82:60–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge J.W.B. Smith A.J. Barker S.S., et al. Effect of Gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2231–2239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier N. Hacein-Bey Abina S. Bartholomae C.C., et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R. Kaplan R.S. Activity-based systems: measuring the costs of resource usage. Accounting Horizon. 1992;6:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cornetta K. Matheson L. Ballas C. Retroviral vector production in the National Gene Vector Laboratory at Indiana University. Gene Ther. 2005;12:S28–S35. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber G.K. Weiss L. Core Facilities: Maximizing the return on investment. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:1–3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley R. A framework for managing core facilities within the research enterprise. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques. 2009;20:226–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horngren C.T. Process costing in perspective: Forget FIFO. The Accounting Review. 1967;42:593–96. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire A.M. Simonelli F. Pierce E.A., et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. New Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R.A. Dudley M.E. Wunderlich J.R., et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani A.C. Tuddenham E.G. Rangarajan S., et al. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. New Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2357–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Request for comment on FAQs to explain costing issues for core facilities. 2010. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-10-138.html. [Oct 29;2012 ]. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-10-138.html

- Porter D.L. Levine B.L. Kalos M. Bagg A., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. New Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Circular A-21 Title 2: Grants and agreements. PART 220—Cost principles for educational institutions. http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title02/2cfr220_main_02.tpl. [Oct 29;2012 ]. http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title02/2cfr220_main_02.tpl