Abstract

Introduction:

Unlike older smokers, young adult smokers frequently engage in light and intermittent smoking. It remains unclear how stable such smoking patterns are over time, as substantial variability exists between these smokers. This study identified subgroups of college student smokers based on the trajectory of their smoking frequency during the first year of college, thereby examining stability versus instability over time. We then tested if the interplay between drinking and smoking differed in the identified groups to determine the relative role drinking may play in intermittent versus more regular smoking.

Methods:

Incoming college students at 3 institutions completed online biweekly surveys of their daily substance use throughout the first year of college. Students who reported smoking at least 1 cigarette during this year (n = 266) were included in analyses (70% female, 74% White).

Results:

Group-based trajectory modeling identified 5 groups of smokers, 3 of which maintained their smoking frequency throughout the year (77%), and 2 groups of infrequent smokers showed significant trends (11% increasing, 12% decreasing). Notably, nondaily smoking was maintained at different specific frequencies (e.g., 1 vs. 3 days per week). Identified groups differed in the relationship between drinking and smoking, where cooccurrence was particularly strong among infrequent smokers, and trends in smoking quantity differed between groups.

Conclusions:

While there was a diversity of smoking patterns in the sample, patterns of intermittent smoking remain relatively stable for a majority of students throughout the year. Intervention messages targeting drinking and smoking should be tailored on the basis of smoking frequency.

INTRODUCTION

Young adults (18–24 years of age) are the age group with the highest rates of current cigarette smoking in the United States, with a prevalence rate of 23.9% (i.e., 100+ cigarettes lifetime, and currently smoking every day or some days; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Unlike tobacco use in older age groups, however, tobacco use during this developmental period is often characterized by light and intermittent smoking. Among all adult smokers, 24.0% report smoking only on some days (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003), but these rates exceed 60% in young adult smokers (Lenk, Chen, Bernat, Forster, & Rode, 2009) and are as high as 70% in college student smokers (Sutfin et al., 2012). Thus, intermittent smoking is a common pattern of young adult smoking, and particularly so in college student smokers.

Although intermittent smoking may be perceived to be less harmful than daily smoking, it is associated with poor health outcomes (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). Among college students, a recent 4-year longitudinal study (n = 1,253) linked intermittent smoking to adverse health effects during college (Caldeira et al., 2012). Further, a multisite health screening survey (n = 2,091) found intermittent smoking among college students to be associated with greater utilization of emergency and mental health services (Halperin, Smith, Heiligenstein, Brown, & Fleming, 2010). Thus, intermittent smoking in college is reason for concern from a public health perspective.

Understanding trajectories of intermittent smoking is important to evaluate the likelihood with which intermittent smokers may “mature out of” smoking, escalate their smoking, or maintain intermittent patterns long term. Evidence to date on this point has been mixed. Older, cross-sectional evidence suggests an increase in smoking more than 4 years of college (Wechsler, Rigotti, Gledhill-Hoyt, & Lee, 1998). By contrast, a population-based 4-year longitudinal survey of adult smokers (n = 3,083) indicated that most light and intermittent smoking is not a gateway to heavier smoking (Levy, Biener, & Rigotti, 2009). A more fine-grained (i.e., daily) longitudinal study on college students (n = 496) (Colder et al., 2006) noted decreases in smoking in college, both in terms of the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the proportions of students reporting smoking. This study also noted substantial variability in smoking between individuals, which makes it difficult to know whether trends generalize to all types and frequencies of smoking.

Subsequent studies of the longitudinal trajectories of smokers have differentiated smokers who exhibit stable, increasing, or decreasing patterns, but these studies have differed on their conclusions as to the stability of intermittent smoking. White, Bray, Fleming, and Catalano (2009) examined biannual data of high school seniors (n = 990) followed for 2 years and found that less than half of the light and intermittent smokers maintained their intermittent smoking pattern 2 years later, whereas 79% of heavy smokers remained heavy smokers. These results were similar to an earlier survey on introductory psychology college students (n = 698), which found that few intermittent smokers maintained their smoking pattern (35%), while most changed it by either quitting (51%) or progressing to daily smoking (14%) over the course of 4 years (Wetter et al., 2004). Other longitudinal trajectory studies, however, point to more stable patterns of light and intermittent smoking (Caldeira et al., 2012; Klein, Bernat, Lenk, & Forster, 2013). A 4-year annual longitudinal study grouped college student smokers based on their smoking frequency (i.e., number of days smoked in the past 30 days) and found that among low-frequency smokers, stability (67%) was more common than increasing patterns (33%). Similarly, another 4-year cohort study (Klein et al., 2013), this time on nondaily young adult smokers, not just college student smokers, identified low (48%), medium (28%), and high (24%) frequency smokers, who maintained relatively stable smoking patterns; only high frequency smokers (>18 smoking days in 30 days) showed increases in smoking frequency. In summary, there is considerable variability in the findings about the stability of intermittent smoking in college. To better understand shifts (or stability) in smoking frequency, an examination of fine-grained (i.e., week-to-week) smoking patterns appears to be warranted.

Evidence to date also suggests that intermittent smokers are quite different from daily smokers in a number of important ways, including smoking motives, perceived nicotine dependence, and interest in quitting smoking. Compared with daily smokers, intermittent smokers tend to smoke for social rather than affect regulation reasons (Berg, Ling, et al., 2012) and tend to emphasize motives associated with acute, situational smoking (e.g., cue exposure, positive reinforcement) rather than dependence-related motives (e.g., tolerance, craving, automaticity) (Shiffman, Dunbar, Scholl, & Tindle, 2012). Young adult nondaily smokers also often report feeling less addicted than young adult daily smokers (Lenk et al., 2009). Indeed, many college student smokers do not consider themselves to be smokers (Berg et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2007). Contrary to these perceptions, evidence indicates that symptoms of nicotine dependence can be seen even among relatively low level nondaily college student smokers (Dierker et al., 2007) and very early (<20 cigarettes lifetime) nondaily smokers (Savageau, Mowery, & DiFranza, 2009). Yet, consistent with intermittent smokers’ optimistic perceptions of their own nicotine dependence, intermittent college smokers are more likely than daily smokers to have made a quit attempt (Berg, Sutfin, Mendel, & Ahluwalia, 2012) and up to 56.8% plan to quit before graduation (Thompson et al., 2007).

Given the importance of the social context in young adult smoking in general and college student smoking in particular, the specific role of drinking in intermittent and more regular smoking becomes of interest. Data from the 2001 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study (student n = 10,924; 120 colleges) show that more than 98% of current college smokers also drink (Weitzman & Chen, 2005). In first-year college students, the vast majority of all smoking episodes (74%) occur while under the influence of alcohol (McKee, Hinson, Rounsaville, & Petrelli, 2004). These data illustrate that smoking and drinking frequently occur together, but the specific role of alcohol in smoking may differ between intermittent and more regular smokers. For example, both intermittent and regular smokers report increased smoking while drinking and increased pleasure and desire when smoking while drinking, but in intermittent smokers, this increase was greater (Harrison, Hinson, & McKee, 2009). Moreover, both drinking and smoking show a strong weekday periodicity, with use elevated on weekends compared with weekdays (Colder et al., 2006; Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Mundt, Searles, Perrine, & Helzer, 1995). This weekday periodicity is particularly pronounced in light smokers (Jackson, Colby, & Sher, 2010). Recent research also suggests that intermittent smoking may be more closely tied to hazardous drinking than daily smoking (Harrison, Desai, & McKee, 2008). A recent analysis of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions data showed that the odds of being a hazardous drinker were 16 [9.46–26.48] times greater in a nondaily smoker compared with a nonsmoker, whereas the odds for a daily smoker were increased by sevenfold [5.54–9.36]. Taken together, current evidence suggests that drinking and smoking may cooccur differently in intermittent versus more frequent smokers and that different types of smoking convey different drinking-related risks.

The primary objective of this study was to identify subgroups of college student smokers based on the trajectory of their smoking frequency during the first year of college, so as to provide further information about the relative stability versus instability of intermittent smoking in this important population of smokers. We then tested if the interplay between drinking and smoking differed in the identified groups, so as to determine the relative role drinking may play in intermittent versus more regular smoking. To this end, we examined both the cooccurrence and amounts of drinking and smoking.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were incoming first-year college students, who were recruited during the summer to participate in a 2-year longitudinal study to evaluate naturalistic changes in alcohol use for typical college students (n = 1,053; 37% recruitment rate). Recruitment occurred in three cohorts, in the summers of 2004, 2005, and 2006. Students were eligible to participate if they were attending high school in the United States, planning to live on campus in college, and enrolled at one of three participating New England universities and colleges. Schools had undergraduate programs of similar size (i.e., 6,000–7,000 undergraduate students each), but differed on selectivity (less selective, selective, and very selective), graduation rate (15%, 30%, and 83%) (http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com), whether first-year students typically lived on campus (i.e., 20%, 66% vs. 100%), and whether the institutions were public or private. Participants were included in the present analyses if they reported smoking at least one cigarette during their first year of college (25.3%), which is similar to the current annual prevalence of cigarette use in college students (25.8%; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). This criterion excluded 18 students who reported any level of current smoking during the summer prior to college attendance (n = 6 daily, n = 12 nondaily) but did not report any smoking during the academic year. The sample (n = 266) was on average 18.4 (SD = 0.4) years old at study entry and was 59.4% female. Participants reported their race as White (74.4%), Asian (7.9%), Black (3.0%), Pacific Islander (1.5%), American Indian (1.9%), and multiracial (8.4%); 9.4% reported being Hispanic.

Procedure

Incoming students received letters inviting them to enroll in the study (for further detail, please refer to Barnett, Orchowski, Read, & Kahler, 2013), and parents of minors received similar letters. Participants completed an online consent procedure, followed by a baseline assessment battery prior to arriving on their college campus. Starting with the first week after arrival on campus, participants received biweekly E-mails containing links to an online survey. Participants were given 1 week to complete each survey and were reminded twice to do so via E-mail. Surveys were conducted throughout the school year, including breaks, resulting in 18 possible surveys in the academic year. Biweekly reports rather than weekly reports were used to reduce response burden (i.e., in any given week only half of the participants were asked to complete surveys). At the end of each semester, participants were paid $2 for each completed survey and a $20 bonus if they completed 85% or more of the surveys each semester. After completing each survey, participants also had a 1 in 50 chance of winning $100. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions.

Measures

Precollege Characteristics

The baseline assessment battery assessed demographics (i.e., age, sex, race) and precollege smoking frequency and number of previous quit attempts. Precollege alcohol experiences were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT: Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993), a 10-item questionnaire that covers the domains of alcohol consumption, drinking behavior, and alcohol-related problems, and the Young Adult Alcohol Problems and Screening Test (YAAPST: Hurlbut & Sher, 1992), where we summed the 20 past-year items recommended by Kahler, Strong, Read, Palfai, & Wood (2004).

Cigarette Use During First Year of College

For the biweekly reports, students completed a 7-day calendar of the number of cigarettes they smoked each day. The online survey link provided a grid with dates for the 7 days prior to the survey completion, starting with yesterday. Thus, for each respondent, there was a flexibly timed 7-day recall period during every a priori determined 14-day interval. For each 7-day recall period, we coded the number of days smoked.

Alcohol Use During First Year of College

Using the same biweekly 7-day survey as for cigarette use, students also reported the number of drinks they consumed each day.

Analytic Strategy

In order to identify subgroups of college student smokers based on their smoking trajectory during the first year of college, we used group-based trajectory modeling, using the SAS procedure Proc Traj (Jones & Nagin, 2007). This approach identifies clusters of individuals who follow a similar trajectory on a specific outcome over time (Nagin & Odgers, 2010). Thus, instead of a priori classifying individuals into groups based on subjective classification rules, this approach uses the longitudinal data to empirically derive trajectory groups. The dependent variable was the number of days students reported smoking each week. In identifying groups, we focused on frequency rather than quantity of smoking because college students themselves define their own smoking status based on the frequency with which they smoke (Berg et al., 2010). The independent variable was time, where we allowed both linear and quadratic trends across the 18 biweekly assessments. We used group-based trajectory modeling rather than growth mixture modeling (GMM) because GMM often collapses groups of differing level; we were equally interested in distinguishing patterns that differed based on overall frequency or changing trends. Following standard group-based modeling practices, we fit models of increasing complexity (i.e., increasing number of groups), until improvements in model fit, as measured by Bayesian information criteria, Akaike’s information criterion, and log likelihood, plateaued and selected the model with optimal fit while being clinically meaningful.

To describe individual differences associated with the smoking trajectories, we tested for significant differences on demographics, and precollege smoking and drinking experiences using logistic or univariate regression tests for categorical versus continuous variables, respectively.

We then examined the day-to-day relationship of smoking and drinking across the first year of college and tested if the identified groups differed on the relationship between drinking and smoking. For these analyses, we used the daily level data (i.e., 126 observations per person). First, we tested if drinking days were correlated with smoking days. To this end, we fit a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model (Liang & Zeger, 1986) in SAS proc genmod, where “smoking day” was the binary dependent variable (1 = smoking day, 0 = no cigarettes smoked that day), which we modeled with a binary distribution and a logit link function. Primary predictors of interest were “drinking day” (1 = any alcoholic drink consumed that day, 0 = no alcoholic drink consumed that day), group membership in the identified trajectory groups, and the interaction term between “drinking day” and “group membership,” which tests if the identified groups differ in their correlation between drinking days and smoking days. Second, we examined if the amount of drinking was related to the amount of smoking. For this model, we restricted the analysis to smoking days (1–126 smoking days per person, with an average of 23±33 and a median of 7.5). Using GEE, we fit a Poisson model for the number of cigarettes smoked on a given smoking day, which is an appropriate model for count data (i.e., integer values rather than continuous data, and no negative values are possible, unlike in a normal distribution). Primary predictors of interest were “number of drinks consumed on that day,” “group membership,” and the interaction term between “number of drinks” and “group membership,” which tests if the identified groups differ in their relationship between number of drinks and number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day.

In both models, we included the following covariates: weekday periodicity (coded as three-level categorical variable: 1 = Sunday–Wednesday, 2 = Thursday, and 3 = Friday & Saturday, with “Friday & Saturday” serving as the references category) because of the strong weekday periodicity oftentimes underlying college student drinking and smoking; a linear trend for time as well as an interaction term between “time” and “group membership” because the identified groups were expected to have differing trends over time.

We included significant predictors of nonresponse in the GEE models examining the relationship of drinking to smoking over time. To identify these predictors of nonresponse, we used a GEE model with the binary dependent variable (1 = nonresponse, 0 = completed biweekly survey) measured on a weekly rather than daily scale. We tested demographics (i.e., sex, race, age), logistical variables (i.e., school of enrollment, linear trend for time), and precollege smoking frequency as potential predictors. In all GEE models, we used an autoregressive correlation structure of the first order (AR1) to account for autocorrelations, where data were modeled as nested within persons. For all models, we used maximum likelihood estimation using all available data, as recommended (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

RESULTS

Compliance With Biweekly Assessments

Participants (n = 266) reported data on average on 108±30.0 days (median = 119, min = 7, max = 126) of the possible 126 days, or 15±4.3 weeks (median = 17, min = 1, max = 18) of the possible 18 weeks. In any given week, nonresponse ranged from 9.0% (biweekly interval #5) to 22.2% (biweekly interval #9; winter break). On a per-person-level, 48% of the participants completed every biweekly survey; 78% completed 80% or more of the surveys. Few participants (12%) failed to complete half or more of all of the biweekly surveys. Sporadic nonresponses (e.g., providing data for fewer than 7 days within the 1-week recall period) occurred in only three (1.1%) participants, for a total of three biweekly reports (< 0.1%) of the 17,856 possible weekly reports.

Significant predictors of biweekly nonresponse were race (χ2(1) = 4.38, p < .05), school (χ2(2) = 11.38, p < .05), and precollege smoking frequency (χ2(2) = 6.54, p < .05). Non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to complete a biweekly report (86.5%) than any other racial or ethnicity group (83.3%). Schools with larger percentage of first-year students living on campus had greater completion rates (79% vs. 83% vs. 89%). Precollege daily smokers, compared with precollege nonsmokers, were less likely to complete a biweekly report (28.0% vs. 11.7%). There was no increasing or decreasing trend in biweekly survey completion across the first year of college (χ2(1) = 0.35, p > .05), and age (χ2(1) = 0.41, p > .05) and sex (χ2(1) = 2.65, p > .05) appeared to be unrelated to biweekly nonresponse.

Identification of Smoking Trajectory Groups

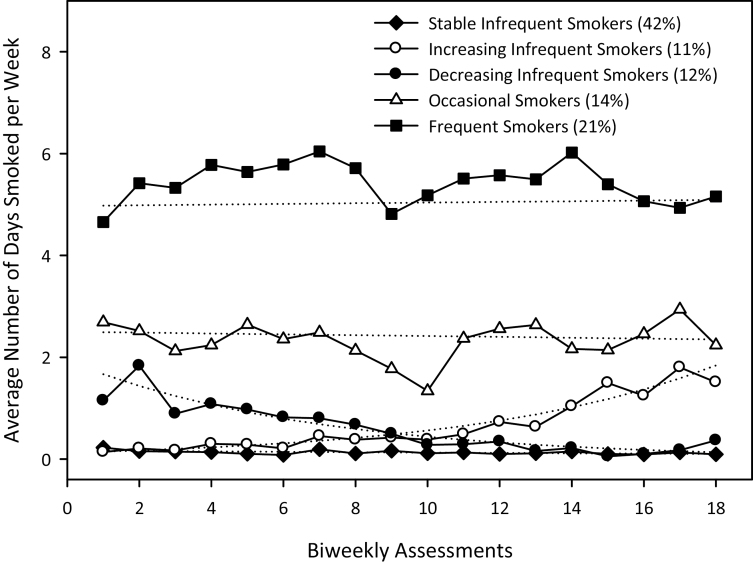

Indices of model fit began to plateau when four groups were differentiated, indicating that increasing model complexity beyond four groups resulted in little improvement in model fit. In inspecting graphs that showed the average and predicted number of days smoked per week, however, for models that retained four, five, and six groups, we found the five-group model to be the most informative, as it differentiated two groups with slight but opposing trends (i.e., Groups 2 and 3). This is the model we retained. Quadratic terms were only significant in one instance; thus, for the sake of parsimony, we dropped quadratic terms from the group-based trajectory model. Identified groups (Figure 1) largely remained the same, with only four participants (1.5%) grouped differently.

Figure 1.

For each identified smoking group, the average number of days smoked per week is shown alongside their predicted values (dotted line), based on the group-based trajectory model. Smoking frequency was relatively stable throughout the first year of college for most smokers (77%), with only some infrequent smokers showing increases (group 2, 11%) or decreases (group 3, 12%) in smoking frequency.

The five groups consisted of three groups of infrequent smokers (Groups 1–3), a stable (42%, Group 1), increasing (11%, Group 2), and decreasing (12%, Group 3) infrequent smoking group, and occasional (14%, Group 4) and frequent (21%, Group 5) smokers. Significant trends over time were observed for the increasing (b = 0.15, t = 7.00, p < .01) and decreasing infrequent (b = −0.15, t = 7.00, p < .01) smoking groups (Table 1), while the other three groups (76.7%) exhibited relatively stable patterns of smoking frequency across the first year of college. Infrequent, occasional, and frequent smokers significantly differed on smoking frequency (F(4,261) = 151.60, p < .01) (Table 2), consistent with the group-based trajectory modeling approach. Frequent smokers also smoked more cigarettes per smoking day than the other four groups (F(4,261) = 47.76, p < .01).

Table 1.

Maximum Likelihood Estimates of Zero-Inflated Group-Based Trajectory Models for Five Groups

| Group | Parameter | Estimate | Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: stable infrequent smokers (42.1%) | Intercept | −1.56 | 0.17 | −9.22** |

| Linear | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.72 | |

| Group 2: increasing infrequent smokers (11.3%) | Intercept | −1.84 | 0.32 | −5.71** |

| Linear | 0.15 | 0.02 | 7.00** | |

| Group 3: decreasing infrequent smokers (12.0%) | Intercept | 0.89 | 0.14 | 6.56** |

| Linear | −0.15 | 0.02 | −8.54** | |

| Group 4: occasional smokers (13.9%) | Intercept | 1.14 | 0.07 | 15.60** |

| Linear | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.65 | |

| Group 5: frequent smokers (20.7%) | Intercept | 1.83 | 0.03 | 54.42** |

| Linear | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | |

| Alpha0 | −1.37 | 0.16 | −8.85** | |

| Alpha1 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.24 |

Note. AIC = Akaike’s information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criteria. BIC = −4995.11 (obs = 4,098); BIC = −4973.23 (n = 266); AIC = −4944.57; L = −4928.57.

**p < .01.

Table 2.

Smoking Frequency and Quantity Across the Identified Groups

| # of days smoked per week | # of cigarettes smoked per smoking day | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Group 1: stable infrequent smokers (42.1%) | 0.14 (0.10) | 1.63 (1.11)a |

| Group 2: increasing infrequent smokers (11.3%) | 0.68 (0.31)a | 1.83 (0.70)a |

| Group 3: decreasing infrequent smokers (12.0%) | 0.70 (0.34)a | 2.06 (1.15)a |

| Group 4: occasional smokers (13.9%) | 2.36 (0.78) | 2.33 (0.95)a |

| Group 5: frequent smokers (20.7%) | 5.66 (1.42) | 6.32 (4.28) |

Note. Values with the same superscript do not differ pairwise from each other at p < .05.

School-Entry Differences Between Smoking Trajectory Groups

The five groups of smokers were comparable in terms of sex, race, and age (Table 3) but differed on precollege smoking characteristics and alcohol experiences. As would be expected, students who were frequent smokers during the first year of college more frequently described themselves as smoking every day precollege (49%) than the other four groups (8% of occasional smokers, <1% of infrequent smokers) (χ2(4) = 30.2, p < .01). Precollege intermittent smoking status (i.e., smoking on some days) differed across identified groups, with decreasing infrequent (44%), occasional (49%), and frequent smokers (33%) all indicating precollege intermittent smoking more often than stable infrequent smokers (18%) (χ2(4) = 16.3, p < .01). Conversely, infrequent smokers more frequently described themselves as nonsmokers prior to college (>56%) than occasional (43%) or frequent smokers (18%), though pairwise differences were not always significant. The smoking groups also differed on whether or not they had made a 24-hr quit attempt in the previous year, with frequent smokers indicating so (54%) more often than infrequent smokers (≤20%). Even among infrequent smokers, however, there were quit attempts. In terms of precollege alcohol experiences, the five groups of smokers differed on both YAAPST and AUDIT scores. Frequent smokers had higher YAAPST scores than stable infrequent smokers (t(261) = 3.75, p < .01) and higher AUDIT scores than stable and increasing infrequent smokers (t(261) = 2.20 and 3.50, p < 0.01, respectively).

Table 3.

Smoking Characteristics of the First-Year College Smoking Trajectory Groups

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | F/χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable infrequent smokers (n = 112) | Increasing infrequent smokers (n = 30) | Decreasing infrequent smokers (n = 32) | Occasional smokers (n = 37) | Frequent smokers (n = 55) | ||

| 42.1% | 11.3% | 12.0% | 13.9% | 20.7% | ||

| Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | Mean/% (SD) | ||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex (female) | 59.8 | 56.7 | 46.9 | 59.5 | 67.3 | 3.6 |

| Race (White) | 73.2 | 70.0 | 78.1 | 67.6 | 81.8 | 3.1 |

| Age | 18.4 (0.4) | 18.4 (0.4) | 18.3 (0.6) | 18.4 (0.5) | 18.4 (0.5) | 0.3 |

| Precollege smoking characteristics | ||||||

| Smoking frequency | 124.3** | |||||

| Every day† | 0.9a | 0.0ab | 0.0ab | 8.1a | 49.1b | |

| Some days† | 17.9a | 30.0ab | 43.8b | 48.7b | 32.7b | |

| Not at all† | 81.3a | 70.0ab | 56.3bc | 43.2c | 18.2 | |

| Made 24-hr quit attempt | 9.8a | 20.0ab | 15.6ab | 35.1bc | 54.6c | 37.6** |

| Precollege alcohol experiences | ||||||

| YAAPST | 2.7 (2.3)a | 2.8 (2.5) ab | 3.3 (2.4)ab | 2.9 (2.1)ab | 4.3 (3.0) b | 3.4** |

| AUDIT | 5.9 (5.0)a | 4.6 (3.6)a | 6.3 (4.9)ab | 5.6 (4.1)ab | 8.1 (5.1)b | 3.1* |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; YAAPST = Young Adult Alcohol Problems and Screening Test.

†For pairwise comparisons across groups, this response category was compared against the other two combined; values with the same superscript do not differ pairwise from each other.

**p < .01.

Day-to-Day Relationship of Smoking and Drinking

The results of the binary GEE model predicting smoking days indicated that the identified groups of smokers differed in the extent to which drinking and smoking days cooccurred (χ2(4) = 49.13, p < .01).

For each of the groups, the estimated probability of a day being a smoking day was greater for drinking than nondrinking days, as indicated an overall main effect for drinking days (χ2(4) = 50.98, p < .01), and by each group’s adjusted odds ratio (AOR) exceeding one (Table 4). This effect was greatest in stable infrequent smokers (AOR = 3.29 vs. AOR ≤ 2.25 with nonoverlapping CIs). It was smallest in frequent smokers (AOR = 1.27), where it was significantly smaller than in infrequent smokers (AOR ≥ 1.86 with nonoverlapping CIs). Please note that ORs were adjusted for weekday and predictors of noncompliance (i.e., race [non-Hispanic White vs. other], institution attended, and precollege smoking frequency).

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) of a Given Day Being a Smoking Day, Given Alcohol Consumption on That Day

| AOR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|

| Group 1: stable infrequent smokers (42.1%) | 3.29 [2.74–3.96]** |

| Group 2: increasing infrequent smokers (11.3%) | 1.86 [1.59–2.17]** |

| Group 3: decreasing infrequent smokers (12.0%) | 2.25 [1.89–2.69]** |

| Group 4: occasional smokers (13.9%) | 1.56 [1.36–1.78]** |

| Group 5: frequent smokers (20.1%) | 1.27 [1.13–1.42]** |

Note. Adjusted for type of weekday, race (non-Hispanic White vs. other), institution attended, and precollege smoking frequency.

**p < .01.

The results of the Poisson GEE model predicting the number of cigarettes smoked on smoking days did not indicate group differences in the relationship between the amounts of drinking and smoking (χ2(4) = 8.53, p = .07), nor was there a main effect for the number of drinks consumed on a given day (χ2(4) = 3.20, p = .07), largely due to the lack of effect in the stable infrequent smokers, the largest of the identified groups, as illustrated for descriptive purposes in Figure 2A. There were, however, group differences in trends over time (χ2(4) = 10.33, p = .04), as illustrated in Figure 2B. Follow-up analyses, in which we refit the same model with a different group serving as the reference group, showed that increasing infrequent smokers increased not just their smoking frequency but also their smoking quantity (b = 0.003, p = .04), while frequent smokers decreased their number of cigarettes smoked per day (b = −0.002, p = .02).

Figure 2.

For each group, the estimated number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day is graphed. Panel A depicts the relationship with regard to the number of drinks consumed on the same day. Group differences were not significant. Panel B depicts trends over time. Compared to stable infrequent smokers (whose increase is not statistically significant), increasing infrequent smokers (group 2) increased not just their smoking frequency but also their smoking quantity, while frequent smokers (group 5) decreased their number of cigarettes smoked per day. These estimates were adjusted for type of weekday, race (non-Hispanic White vs. other), institution attended, and precollege smoking frequency.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used first-year college students’ daily reports of smoking to identify subgroups with differing smoking frequency trajectories. We identified five groups of smokers, only two of which changed their smoking frequency significantly during the first year of college (representing 23% of smokers). Both groups were infrequent smokers, who smoked on average on less than 1 day a week and approximately two cigarettes per smoking day. Trends were in opposite directions, with one group increasing (11%) and the other decreasing (12%) smoking frequency during the first year of college.

The other three groups (83% of smokers) had stable smoking patterns throughout the school year. These results are similar to those of other recent longitudinal trajectory studies (Caldeira et al., 2012; Klein et al., 2013) that likewise indicate a relative stability in intermittent smoking patterns. They differ from the findings by White et al. (2009), which suggest a greater instability in intermittent smoking patterns. This discrepancy could be due to differences in defining intermittent smoking. In the study by White et al. (2009), participants were grouped into “nonsmokers,” “light and intermittent smokers,” and “heavy smokers” based on their report of the number of cigarettes they smoked per day in the past month, rather than an indication of their smoking frequency. This grouping combines light and intermittent smokers into a rather heterogeneous group, among which intermittent smokers tend to be the most stable smokers (Husten, 2009). Taken together, our findings and previous findings from longitudinal trajectory modeling suggest that smoking frequency appears to be relatively stable for a majority of college student smokers. Our findings extend current evidence by showing that not just the designation of “nondaily” (vs. daily) is relatively stable but that varying nondaily frequencies (e.g., 3 vs. 1 smoking days per week) can be maintained for at least 1 year.

Regarding the role of alcohol, we found that alcohol was linked to the occurrence of smoking, particularly so in infrequent smokers and less so in frequent smokers. Alcohol and smoking quantities, however, were not significantly linked in our sample, possibly due to insufficient power. Encouragingly, we also found that smoking consumption (i.e., the number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day) appeared to be increasing in only one group, increasing infrequent smokers (11.3%), who increased both their smoking frequency and quantity during the first year of college. All other groups either exhibited stable (68%) or declining (21%) smoking quantities, where it is particularly encouraging that frequent smokers were showing a declining trend in the number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day.

Our findings have implications for tailoring intervention messages. First of all, our data are in line with evidence that suggests that college student smokers are open to smoking cessation (Berg, Sutfin, et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2007). Transitioning into lesser frequent smoking patterns as a partial quit success did not appear to be dominant theme (only <1% of infrequent smokers and 8% of occasional smokers were precollege daily smokers). Encouragingly, however, prior quit attempts were common among frequent smokers (55%) and numerous in less frequent smokers (10%–35%). Thus, our findings suggest that even infrequent smokers could benefit from cessation aides. Second, alcohol appears to be strongly related to smoking in first-year college students, but differentially so for smokers of differing smoking frequency. Thus, intervention messages regarding drinking and smoking might need to vary for smokers of different smoking frequency. For infrequent smokers, it may be particularly important to set goals not to smoke when drinking and socializing.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include its longitudinal, fine-grained assessment schedule, which enabled examination of trends as they developed over time. The biweekly, online assessments also minimized recall biases, providing strong internal validity of the data. It should be kept in mind, however, that smoking and drinking were assessed by self-report, and it is possible that students underreported their use. Self-report was also only assessed on a daily level, so that it is not clear if drinking and smoking happened at the same time, or simply on the same day. Data were collected on multiple campuses, thereby increasing generalizability of the findings. Given the relatively low prevalence of smoking among college students, however, even a large sample of more than 1,000 students yielded a sample of only 266 smokers, thereby limiting generalizability and statistical power. Our recruitment rate (37%) further limited generalizability. The study was also originally designed with a focus on alcohol use, and thus a limited number of smoking variables were assessed.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that intermittent smoking occurs at a variety of frequency levels in first-year college students. Moreover, these patterns of intermittent smoking remain relatively stable for a majority of students throughout the year, suggesting a degree of stability. Young adulthood, however, is marked by many changes in substance use patterns that span a longer period of time. Therefore, it is possible that transitions in smoking behavior will occur outside the period of observation in this study. In future research, it would be important to extend our findings by examining what happens to these students over the course of their college career and beyond. Further, although intermittent smokers may only reach low levels of nicotine dependence, our data suggest they may still be in need of tailored interventions in order to quit successfully. The tailoring of intervention messages is particularly important, as our data show that less frequent smoking is tied more closely to drinking days and thereby likely driven by external stimuli and social motives. By contrast, existing smoking cessation materials have been developed based on daily smoking, where the role of internal cues and motives is likely to play a substantially larger role than in intermittent smoking.

FUNDING

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA013970) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA027097, K23DA033302).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Barnett N. P., Orchowski L. M., Read J. P., Kahler C. W. (2013). Predictors and consequences of pregaming using day- and week-level measurements. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 10.1037/a0031402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. J., Ling P. M., Hayes R. B., Berg E., Nollen N., Nehl E., Ahluwalia J. S. (2012). Smoking frequency among current college student smokers: Distinguishing characteristics and factors related to readiness to quit smoking. Health Education Research, 27, 141–150. 10.1093/her/cyr106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. J., Lust K. A., Sanem J. R., Kirch M. A., Rudie M., Ehlinger E., An L. C. (2009). Smoker self-identification versus recent smoking among college students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36, 333–336. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. J., Parelkar P. P., Lessard L., Escoffery C., Kegler M. C., Sterling K. L., Ahluwalia J. S. (2010). Defining “smoker”: College student attitudes and related smoking characteristics. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 963–969. 10.1093/ntr/ntq123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. J., Sutfin E. L., Mendel J., Ahluwalia J. S. (2012). Use of and interest in smoking cessation strategies among daily and nondaily college student smokers. Journal of American College Health, 60, 194–202. 10.1080/07448481.2011.586388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K. M., O’Grady K. E., Garnier-Dykstra L. M., Vincent K. B., Pickworth W. B., Arria A. M. (2012). Cigarette smoking among college students: Longitudinal trajectories and health outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14, 777–785. 10.1093/ntr/nts131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking—United States, 1996–2001. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5214a2.htm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5644a2.htm [Google Scholar]

- Colder C. R., Lloyd-Richardson E. E., Flaherty B. P., Hedeker D., Segawa E., Flay B. R. (2006). The natural history of college smoking: Trajectories of daily smoking during the freshman year. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 2212–2222. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca F. K., Darkes J., Greenbaum P. E., Goldman M. S. (2004). Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 155–164. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L. C., Donny E., Tiffany S., Colby S. M., Perrine N., Clayton R. R. (2007). The association between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among first year college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 106–114. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin A. C., Smith S. S., Heiligenstein E., Brown D., Fleming M. F. (2010). Cigarette smoking and associated health risks among students at five universities. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 96–104. 10.1093/ntr/ntp182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison E. L., Desai R. A., McKee S. A. (2008). Nondaily smoking and alcohol use, hazardous drinking, and alcohol diagnoses among young adults: Findings from the NESARC. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 2081–2087. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00796.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison E. L., Hinson R. E., McKee S. A. (2009). Experimenting and daily smokers: Episodic patterns of alcohol and cigarette use. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 484–486. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut S. C., Sher K. J. (1992). Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41, 49–58. 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten C. G. (2009). How should we define light or intermittent smoking? Does it matter? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11, 111–121. 10.1093/ntr/ntp010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Colby S. M., Sher K. J. (2010). Daily patterns of conjoint smoking and drinking in college student smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 424–435. 10.1037/a0019793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E. (2012). Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Retrieved from www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. L., Nagin D. S. (2007). Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociological Methods & Research, 35, 542–571. 10.1177/0049124106292364 [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Strong D. R., Read J. P., Palfai T. P., Wood M. D. (2004). Mapping the continuum of alcohol problems in college students: A Rasch model analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 322–333. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E. G., Bernat D. H., Lenk K. M., Forster J. L. (2013). Nondaily smoking patterns in young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 38, 2267–2272. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk K. M., Chen V., Bernat D. H., Forster J. L., Rode P. A. (2009). Characterizing and comparing young adult intermittent and daily smokers. Substance Use and Misuse, 44, 2128–2140. 10.3109/10826080902864571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. E., Biener L., Rigotti N. A. (2009). The natural history of light smokers: A population-based cohort study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11, 156–163. 10.1093/ntr/ntp011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K. Y., Zeger S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73, 13–22. 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13 [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. A., Hinson R., Rounsaville D., Petrelli P. (2004). Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6, 111–117. 10.1080/14622200310001656939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt J. C., Searles J. S., Perrine M. W., Helzer J. E. (1995). Cycles of alcohol dependence: Frequency-domain analyses of daily drinking logs for matched alcohol-dependent and nondependent subjects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S., Odgers C. L. (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 109–138. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J. B., Aasland O. G., Babor T. F., de la Fuente J. R., Grant M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savageau J. A., Mowery P. D., DiFranza J. R. (2009). Symptoms of diminished autonomy over cigarettes with non-daily use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6, 25–35. 10.3390/ijerph6010025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J. L., Graham J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. :10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Dunbar M. S., Scholl S. M., Tindle H. A. (2012). Smoking motives of daily and non-daily smokers: A profile analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126, 362–368. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin E. L., McCoy T. P., Berg C. J., Champion H., Helme D. W., O’Brien M. C., Wolfson M. (2012). Tobacco use by college students: A comparison of daily and nondaily smokers. American Journal of Health Behavior, 36, 218–229. 10.5993/AJHB.36.2.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B., Coronado G., Chen L., Thompson L. A., Halperin A., Jaffe R., Zbikowski S. M. (2007). Prevalence and characteristics of smokers at 30 Pacific Northwest colleges and universities. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9, 429–438. 10.1080/14622200701188844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Retrieved from www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/tobaccosmoke/executivesummary.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Rigotti N. A., Gledhill-Hoyt J., Lee H. (1998). Increased levels of cigarette use among college students: A cause for national concern. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1673–1678. joc80656 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman E. R., Chen Y. Y. (2005). The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: National survey results from the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 80, 377–386. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter D. W., Kenford S. L., Welsch S. K., Smith S. S., Fouladi R. T., Fiore M. C., Baker T. B. (2004). Prevalence and predictors of transitions in smoking behavior among college students. Health Psychology, 23, 168–177. :10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. R., Bray B. C., Fleming C. B., Catalano R. F. (2009). Transitions into and out of light and intermittent smoking during emerging adulthood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11, 211–219. 10.1093/ntr/ntn017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]