Abstract

Introduction:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prevalence and correlates of use of nicotine-containing tobacco products such as cigars, pipe tobacco, and cigarettes that promise less exposure to toxins; e-cigarettes; and smokeless tobacco products among a cohort of conventional cigarette smokers followed over the past decade. We also evaluated associations between use of such products and cigarette quitting.

Methods:

Participants were 6,110 adult smokers in the United States, who were interviewed as part of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey between 2002 and 2011. Respondents reported their concurrent use of other smoked tobacco products (including cigars, pipe tobacco, and cigarillos), smokeless tobacco products (including chewing tobacco, snus, and snuff), unconventional cigarettes (including Omni, Accord, and Eclipse), and electronic cigarettes. Prevalence and correlates of use and associations between use and cigarette quitting were assessed using regression analyses via generalized estimating equations.

Results:

Most cigarette smokers did not use unconventional tobacco products, although use of any of these products started to rise at the end of the study period (2011). For each type of tobacco product evaluated, use was most prevalent among those aged 18–24 years. Smokers who did use unconventional tobacco products did not experience a clear cessation advantage.

Conclusions:

During the past decade, relatively few cigarette smokers reported also using other tobacco products. Those that did use such products were no more likely to stop using conventional cigarettes compared with those who did not use such products.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes tobacco products into two broad classes: those that are smoked (combustible) and those that are not (noncombustible, also called “smokeless”). Within the combustible category are conventional cigarettes and other smoked tobacco products, including cigars, pipe tobaccos, water pipe tobaccos, roll-your-own (RYO) cigarettes, bidis, and kreteks. The noncombustible category includes various forms of chewing tobacco, moist snuff, dry snuff, and the newer e-cigarette electronic nicotine delivery products. According to WHO, both combustible and noncombustible tobacco products pose health risks to the user though the health risks of combustible products are generally greater than those of noncombustible products because the process of burning tobacco generates toxicants. Conventional cigarettes are associated with the highest levels of disease because their designs and ingredients result in the highest exposures to toxicants. Cigarettes deliver mildly acidic smoke that is more readily inhaled into the lungs with less discomfort than the alkaline smoke from most pipes and cigars. Absorption of nicotine in the lung is particularly addictive because it very rapidly results in delivery of dependence-inducing doses of nicotine to the brain, establishing the repetitive and persistent smoke self-administration characteristics of the majority of smokers (WHO, in press).

Smokers of conventional cigarettes who are interested in products that they may perceive as potentially reducing exposure to harmful constituents may turn to other nicotine- containing tobacco products such as cigars, pipe tobacco, cigarettes that promise less exposure to toxins, e-cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco products. Since exposure to toxins from smoking conventional cigarettes is primarily the result of the combustion process, substituting cigarettes with noncombusted products such as smokeless tobacco or e-cigarettes could theoretically reduce the adverse health consequences caused by cigarette smoking among those who would not have quit tobacco entirely (Levy et al., 2004, 2006; Royal College of Physicians, 2007). For example, it has been demonstrated that e-cigarette vapor contains lower levels of carcinogens and toxicants than cigarette smoke (Goniewicz et al., 2013; McAuley, Hopke, & Zhao, 2012), which could theoretically reduce smoking-related disease rates if cigarette smokers who would not otherwise quit would completely switch to e-cigarettes. On the other hand, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) warns that availability of other tobacco products may have a net negative impact on public health since smokers might delay or refrain from quitting, former smokers may be drawn back to tobacco use, and nonsmokers might be encouraged to start using tobacco (IOM, 2012). Therefore, evaluating the net impact of these other tobacco products (hereafter referred to as unconventional tobacco products) on public health is an important and complex question (Bombard, Rock, Pederson, & Asman, 2008; Hatsukami et al., 2002; Hatsukami, Ebbert, Feuer, Stepanov, & Hecht, 2007; O’Connor, 2012; Shiffman et al., 2002).

In 2009, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act gave the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate all tobacco products, with immediate jurisdiction over cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and RYO tobacco (Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act [FSPTCA], Public Law 111–31). As a result, manufacturers of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, or RYO tobacco who want to market their products as “modified risk” must now obtain authorization to do so; a report produced by the IOM, commissioned by the FDA, calls for evaluation of the scientific evidence pertaining to the use, perceptions, and potential for risk reduction of these products (IOM, 2012). Currently, several types of tobacco products such as cigars, pipe tobacco, and e-cigarettes are not encompassed by FDA regulation. However, FDA can assert regulatory authority through rulemaking and has announced that it will propose a rule deeming products that meet the definition of a tobacco product to be subject to FDA’s jurisdiction (Federal Register 163).

The extent to which any tobacco products may serve as risk-reducing agents depends in part on cigarette smokers’ use of them. Among cigarette smokers, use of cigars, cigarillos, and little cigars is highest among males, adolescents/young adults, and minorities (Richardson, Xiao, & Vallone, 2012). Further, Schuster, Hertel, and Mermelstein (2012) found that use of these products among adolescents was positively correlated with alcohol use and antisocial behavior. Data are limited with regard to how cigar use influences cessation from cigarette smoking although recent studies have reported that many cigarette smokers have switched to little cigars because of their lower price (Cullen et al., 2011; Delnevo, 2006).

Several studies evaluating the use of smokeless tobacco among smokers of conventional cigarettes have found that dual use is most prevalent among males and young adults (Bombard, Pederson, Nelson, & Malarcher, 2007; Bombard et al., 2008; Tomar, 2002; Wetter et al., 2002), and U.S.-based studies suggest that it may interfere with cigarette cessation. For example, Wetter et al. (2002) found that, among adult smokers, those who used both cigarettes and smokeless tobacco were less likely to stop all tobacco use than were those who only used one product or the other. Tomar, Alpert, and Connolly (2010) found that unsuccessful attempts to quit smoking were more prevalent among males who used snuff than among those who did not. Zhu et al. (2009) found no advantage in cessation for men who switched to smokeless tobacco. However, several studies conducted in Sweden, where use of snus is relatively common among men, have concluded that males who use snus have greater odds of quitting cigarette smoking than those who do not use snus (Furberg et al., 2005; Gilljam & Galanti, 2003; Ramström & Foulds, 2006).

Little data are available on how smokers have used unconventional products promoted as less toxic such as Omni, Accord, and Eclipse, all of which are largely no longer available in the United States. Shiffman, Pillitteri, Burton, and Di Marino (2004) did show that simulated ads describing Eclipse reduced intentions to quit among smokers, and Hughes, Keely, and Callas (2005) showed that Eclipse users were no more or less likely to have quit at 6 months follow-up compared with other smokers. More recently, several studies have evaluated the use of e-cigarettes by cigarette smokers, which indicate that smokers report using them to help quit or cut down on smoking (Adkison et al., 2013; Etter, 2010; Etter & Bullen, 2011; Pearson, Richardson, Niaura, Vallone, & Abrams, 2012; Pokhrel, Fagan, Little, Kawamoto, & Herzog, 2013; Regan, Promoff, Dube, & Arrazola, 2013; Vickerman, Carpenter, Altman, Nash, & Zbikowski, 2013). None of the unconventional tobacco products evaluated in this study have been approved as smoking cessation aids.

The purpose of this study was (a) to determine the demographic and smoking-related predictors of cigarette smokers’ use of unconventional tobacco products (i.e., other smoked tobacco products, smokeless tobacco products, unconventional cigarettes, and e-cigarettes); (b) to evaluate demographic predictors of use of these products as an alternative to quitting smoking, to cut down on conventional cigarette smoking, and to help quit conventional cigarette smoking; and (c) to evaluate the association between unconventional tobacco product use and cigarette quitting. These efforts will help inform the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study in addressing the FDA’s tobacco regulatory mission under the FSPTCA by providing comparative data on cigarette smokers’ use of unconventional tobacco products.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 6,110 adult smokers (18+ years of age) in the United States who were interviewed as part of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey (ITC-4) between 2002 and 2011. Beginning in 2002, the ITC-4 recruited current smokers (i.e., those who smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetimes and who reported smoking at least once in the past 30 days) from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, using random digit dialing. Although response rates in the United States were relatively low (ranging from 21% to 35%), previous analyses have confirmed that the demographic profiles of those who responded to this survey were comparable with the profiles of those who responded to national benchmark surveys, suggesting that any nonresponse to this survey is comparable with that of benchmark surveys. (International Tobacco Control [ITC] Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project, 2004; ITC Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project, 2011; Thompson et al., 2006).

Participants were recontacted approximately annually to complete follow-up surveys, and new participants were added each year to offset those lost to attrition (~25%) using the same recruitment procedures as were used at baseline. Since attrition rates differed among different age, gender, and racial/ethnic groups (Thompson et al., 2006), multivariate models used in this study were adjusted for these variables (see Supplementary Table for demographic characteristics of respondents). Detailed descriptions of the survey design, procedures, and limitations have been published elsewhere (Fong et al., 2006; ITC Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project, 2004; ITC Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project, 2011; Thompson et al., 2006). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Waterloo, Canada and Roswell Park Cancer Institute, United States.

Measures

Respondents were queried about their use of each of four families of products: other smoked tobacco products, smokeless tobacco products, unconventional cigarettes, and electronic cigarettes. The exact wording of all items used in each ITC survey can be found at www.ITCproject.org (International Tobacco Control [ITC] Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project, 2012).

Use of Other Smoked Tobacco Products

During each survey wave, respondents were asked, “In the past month, have you used any other tobacco product that is smoked besides cigarettes?” Those who had were classified as “other smoked tobacco product users” and were specifically asked if they used each of the following: cigars, pipes, cigarillos, bidis, hookahs, or other smoked tobacco products. There was no quantity/frequency threshold of use considered when classifying a respondent as a user of other smoked tobacco products. For each type of product used, respondents were asked if they currently use the product (i.e., use at the time of interview), and if so, how often (response options were daily, less than daily but at least once a week, less than weekly but at least once a month, less than monthly, or stopped all together).

Use of Smokeless Tobacco Products

During each survey wave, respondents were asked, “Are you aware of any smokeless tobacco products, such as snuff or chewing tobacco, which are not burned or smoked but instead are usually put in the mouth?” Those who responded affirmatively were asked, “Have you used any smokeless tobacco products in the last 12 months?” Those who reported that they had were classified as “smokeless tobacco users” and were specifically asked if they used each of the following: chewing tobacco, moist snuff or snus, nasal snuff, Ariva, Exalt, or any other smokeless tobacco products. For each product indicated, respondents were asked how often they currently use the product (response options were the same as given in Use of Other Smoked Tobacco Products).

Use of Unconventional Cigarettes

Surveys conducted between 2002 and 2009 included the following item: “Tobacco companies are developing new types of cigarettes or cigarette-like products that are supposed to be less harmful than ordinary cigarettes. Have you heard of such products, outside of these surveys?” Those who responded affirmatively were asked if they could name any such products and, if so, were asked whether they had tried any named products since last survey date (LSD). Respondents who indicated that they had tried Omni, Accord, Eclipse, or Advance were classified as “alternative cigarette users” (alternative cigarettes differ from conventional cigarettes in that they use an electronic heating device, which burns less tobacco than conventional cigarette smoking). If still using the product indicated, respondents were asked how often they use it (with response options being the same as given in the Use of Other Smoked Tobacco Products section). Respondents who freely reported using any of these products when previously asked about use of any other smoked tobacco products were also classified as unconventional cigarette users. Since unconventional cigarette products are largely no longer available on the market in the United States, respondents were not queried about them after 2009.

Use of Electronic Cigarettes

Beginning in the 2010–2011 survey, respondents were asked the following: “Have you ever heard of electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes?” Those who responded affirmatively were asked if they ever tried electronic cigarettes, and if so, how often they currently use them (same response options as given in the Use of Other Smoked Tobacco Products section).

Thoughts About Harmfulness of Each Family of Products

Regardless of use of other smoked tobacco products, respondents were asked the following: “Thinking about all the different types of tobacco products that are smoked - that is, factory-made cigarettes, roll-your-own, pipes, and cigars - are any of these more harmful or are they all equally harmful?” Respondents who indicated that some kinds are less harmful than others were asked which product is the least harmful, and separately, which product is the most harmful. Regardless of use of smokeless tobacco products or unconventional cigarettes, respondents who were aware of these products were asked, “As far as you know, are [products] less harmful than ordinary cigarettes?” Those who responded “yes” were asked if they are a little or a lot less harmful than ordinary cigarettes, and those who responded “no” were asked if they are more harmful or the same (the wave 4 survey only queried product users about their thoughts regarding product harm, thus it was not included in this analysis). Regardless of use of electronic cigarettes, respondents who were aware of these products were asked, “Do you think electronic cigarettes are more harmful than regular cigarettes, less harmful, or are they equally harmful to health?”

Other Uses for Products

Those who were classified as users of other smoked tobacco products, smokeless tobacco products, or unconventional cigarettes were asked if they used each product family indicated “as an alternative to quitting?” and with a separate item “as a way of cutting down on your cigarette smoking?” Users of smokeless tobacco products and users of unconventional cigarettes who indicated that they had made an attempt to quit smoking since LSD (see Quit Attempts and 30-Day Smoking Cessation section) were additionally asked if they used each product family indicated “to help you quit.” For each family of products used, respondents could endorse any number of the foregoing reasons (users of e-cigarettes were asked a different series of items regarding their reasons for use, and since data were only available from one wave, sample size was too small to evaluate predictors of these reasons).

Quit Attempts and 30-Day Smoking Cessation

During each follow-up survey, participants who were smokers at previous interview (all were smokers at baseline) were asked, “Have you made any attempts to stop smoking since we last talked with you?” (which was approximately 1 year ago except for 11% of respondents who participated in an interim survey wave [which was not relevant to the current analyses except that these respondents had a previous interview referent of <1 year]). Respondents were classified as having quit smoking if they maintained 30-day continuous abstinence from cigarette smoking, which was determined at first follow-up among those who attempted to quit more than 1 month prior to this interview, and at next follow-up among those who attempted to quit within 1 month of first follow-up interview (since they did not yet have the chance to reach the 1-month cessation endpoint at first follow-up), as has been done previously with these data (Cooper et al., 2010). Those who quit and later relapsed back to smoking rejoined the analyses of cigarette smokers.

Demographic and Smoking-Related Characteristics

The following covariates were included in analyses: gender, baseline age group (i.e., 18–24, 25–39, 40–54, and 55+; analyses using the continuous age variable produced similar results), racial/ethnic group (i.e., non-Hispanic white/other), level of education (i.e., “low” if completed high school or less, “moderate” if completed community college/trade/technical school/some university (no degree), or “high” if completed university or postgraduate education), annual household income (i.e., “low” if less than $30,000, “moderate” if $30,000–$59,999, or “high” if $60,000 or more; those who did not provide this information [~5%] were included as a valid unknown group), intention to quit (a dichotomous variable measured with the item “Are you planning to quit smoking within the next month, within the next six months, sometime in the future - beyond six months, or are you not planning to quit?”), and nicotine dependence (measured with the heaviness of smoking index (HSI), a short form of the Fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, Rickert, & Robinson, 1989).

Statistical Analyses

For each unconventional tobacco product, prevalence of use was evaluated as a ratio of users among those who were surveyed (referred to as absolute use rates) at each interview wave, over the course of the study period. Among current users of each product (i.e., use at the time of interview), frequency of use was determined.

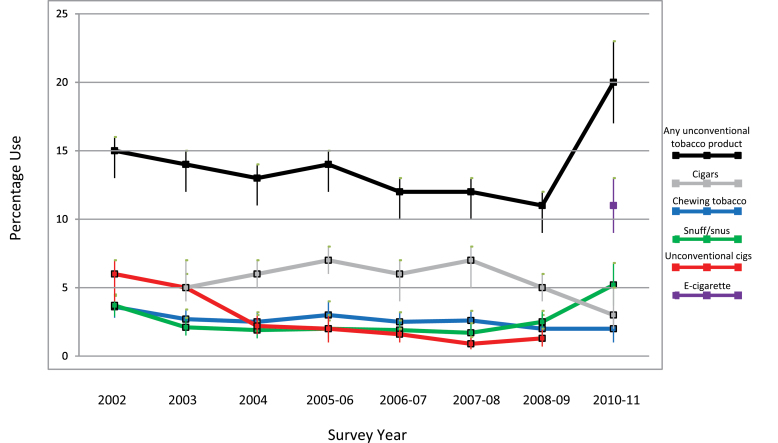

Predictors of use of each family of products were evaluated among those who were aware of the products (referred to as relative use rates) using repeated cross-sectional logistic regression analyses via generalized estimating equations (GEEs; Hardin & Hilbe, 2002; Liang & Zeger, 1986). That is, respondents who were present in multiple survey waves contributed multiple observations, and the inherent absence of independence among these observations was statistically controlled by adjusting for the estimated correlations among observations within respondents. Specifically, an unstructured within-person correlation matrix was specified in each model and confidence intervals were calculated using a robust variance estimator. Four separate GEE models were used to evaluate predictors of use of each of the four families of unconventional tobacco products, and each analysis was adjusted for gender, age group, race/ethnicity, education, income, HSI, and survey year (survey year itself was not evaluated as a predictor in the tables because doing so overlaps with the evaluation of use rates across the study period, see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Absolute prevalence of use (i.e., use rates among all smokers) of various types of unconventional tobacco products by cigarette smokers across the study period (with 95% confidence intervals). Note. For cigars, time frame for product use is within the past month; for chewing tobacco, snuff/snus, and unconventional cigarettes, time frame is within the past 12 months; and for e-cigarettes, time frame is ever tried.

The difference in thoughts about the equality of harmfulness between conventional cigarettes and each family of unconventional tobacco products was assessed as a function of product user status (among those who were aware of the products, i.e., relative use rates) using unconditional cross-sectional GEE logistic regression analyses (same model specifications as predictors of use analyses). That is, four separate models were used to assess whether smokers think conventional cigarettes are as equally harmful as versus are not as equally harmful as (i.e., the outcome) each family of unconventional tobacco products, by unconventional tobacco product user status.

Among those who used each family of unconventional tobacco products (excluding e-cigarettes), unconditional cross-sectional GEE logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the demographic predictors of product use as an alternative to quitting conventional cigarettes, product use to cut down on the amount of conventional cigarettes smoked, and product use to help quit conventional cigarette smoking, using the same model specifications as used in the predictors of use analyses.

For each family of unconventional tobacco products (excluding e-cigarettes due to follow-up data not yet being available), the likelihood of making a quit attempt was assessed as a function of unconventional tobacco product use (using absolute use rates) during the same inter-wave interval using longitudinal logistic regression GEE models (same specifications as used in the predictors of use analyses). For each family of unconventional tobacco products, the likelihood of quitting cigarette smoking, among those who attempted to quit, was assessed as a function of unconventional tobacco product use during the same inter-wave interval using longitudinal regression analyses. Smoking cessation was also assessed among the subset of smokeless tobacco users and, separately, among the subset of unconventional cigarette users, who reported that they used the product to help them quit smoking. Analyses were adjusted for gender, age group, race/ethnicity, education, income, HSI (measured during the preceding year), and survey year. All analyses were conducted using Stata Version 11 (StataCorp, 2009).

RESULTS

Among those who reported using other smoked tobacco products, 70% used cigars, 12% used pipe tobacco, 4% used cigarillos, and 14% used other smoked tobacco products; among those who reported using smokeless tobacco products, 61% used chewing tobacco, 55% used moist snuff/snus, 5% used nasal snuff, and 9% used other smokeless tobacco products (data not shown). Figure 1 shows the absolute prevalence of use of cigars, chewing tobacco, moist snuff/snus (i.e., the largest subcategories for other smoked tobacco products and for smokeless tobacco products), unconventional cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and any unconventional tobacco product across the study period (2002–2011). In general, use of each product was low throughout the study period (<10%) though use of snuff/snus began to rise at the end of the study period. By 2010–2011, 20% of smokers reported using any unconventional tobacco product, with 11% reporting use of e-cigarettes. Less than 2% of respondents reported using more than one family of unconventional tobacco product at any given wave (data not shown). When averaged across the study period, the majority (>60%) of current users of any unconventional tobacco product reported their frequency of product use as being less than once per week (data not shown).

Table 1 shows the relative use rates of each family of products by demographic characteristics. Male cigarette smokers were more likely to use other smoked tobacco products or smokeless tobacco products than were female cigarette smokers. Those aged 18–24 years were more likely to use each of the four families of products than were older smokers. Non-Hispanic whites were more likely to use smokeless tobacco products and were more likely to use e-cigarettes than were minorities. Compared with those with low scores on the HSI, those with high scores were more likely to use other smoked tobacco products or smokeless tobacco products. For each family of unconventional tobacco products, those who used a given product were significantly more likely to report that they believe the product is less harmful than conventional cigarettes compared with their counterparts who did not use the given product (data not shown).

Table 1.

Predictors of Use of Unconventional Tobacco Products Among Cigarette Smokers

| Predictors of use | Other smoked tobacco productsa | Smokeless tobacco productsb,c | Unconventional cigarettesb,c | Electronic cigarettesc,d | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 6,110 (8% use overall) | N = 5,442 (6% use overall) | N = 1,625 (12% use overall) | N = 520 (16% use overall) | |||||||||

| N | % Used | OR (95% CI) | N | % Used | OR (95% CI) | N | % Used | OR (95% CI) | N | % Used | OR (95% CI) | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 3,370 | 4 | Ref | 2,998 | 2 | Ref | 897 | 12 | Ref | 285 | 16 | Ref |

| Male | 2,740 | 13 | 2.86 (2.43–3.36) | 2,444 | 11 | 6.03 (4.67–7.78) | 728 | 13 | 1.14 (0.88–1.48) | 235 | 16 | 0.96 (0.59–1.56) |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 695 | 17 | Ref | 618 | 17 | Ref | 121 | 29 | Ref | 18 | 33 | Ref |

| 25–39 | 1,599 | 9 | 0.45 (0.35–0.57) | 1,444 | 8 | 0.50 (0.38–0.65) | 356 | 15 | 0.49 (0.31–0.77) | 69 | 22 | 0.46 (0.14–1.53) |

| 40–54 | 2,255 | 8 | 0.37 (0.29–0.46) | 2,026 | 4 | 0.18 (0.14–0.24) | 645 | 12 | 0.41 (0.27–0.63) | 245 | 16 | 0.27 (0.09–0.82) |

| 55+ | 1,561 | 4 | 0.18 (0.14–0.24) | 1,354 | 2 | 0.09 (0.06–0.14) | 503 | 8 | 0.27 (0.17–0.42) | 188 | 14 | 0.26 (0.08–0.79) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4,837 | 8 | Ref | 4,406 | 6 | Ref | 1,375 | 12 | Ref | 458 | 17 | Ref |

| Other | 1,273 | 8 | 1.00 (0.83–1.22) | 1,036 | 5 | 0.59 (0.44–0.80) | 250 | 15 | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | 62 | 10 | 0.53 (0.21–1.31) |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Low | 2,790 | 6 | Ref | 2,401 | 7 | Ref | 601 | 12 | Ref | 208 | 12 | Ref |

| Moderate | 2,376 | 8 | 1.41 (1.19–1.68) | 2,171 | 5 | 0.80 (0.64–1.00) | 729 | 14 | 1.31 (0.98–1.74) | 204 | 22 | 2.15 (1.23–3.75) |

| High | 1,012 | 9 | 1.71 (1.37–2.13) | 927 | 4 | 0.53 (0.37–0.74) | 303 | 9 | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 108 | 13 | 1.19 (0.57–2.48) |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| Low | 2,420 | 7 | Ref | 2,088 | 5 | Ref | 573 | 13 | Ref | 178 | 15 | Ref |

| Moderate | 2,171 | 7 | 0.86 (0.71–1.03) | 1,979 | 5 | 1.07 (0.85–1.36) | 591 | 10 | 0.86 (0.63–1.18) | 165 | 15 | 0.92 (0.50–1.71) |

| High | 1,535 | 9 | 1.04 (0.85–1.26) | 1,404 | 7 | 1.27 (0.98–1.64) | 425 | 14 | 1.09 (0.79–1.52) | 140 | 21 | 1.43 (0.77–2.67) |

| Not provided | 439 | 9 | 1.31 (0.97–1.77) | 362 | 6 | 1.31 (0.86–1.99) | 101 | 12 | 0.94 (0.52–1.69) | 37 | 14 | 0.86 (0.30–2.45) |

| HSI | ||||||||||||

| 0–1 | 1,762 | 8 | Ref | 1,518 | 5 | Ref | 415 | 14 | Ref | 68 | 16 | Ref |

| 2–3 | 3,494 | 7 | 1.10 (0.92–1.33) | 3,047 | 6 | 1.26 (0.99–1.60) | 817 | 12 | 0.86 (0.63–1.17) | 296 | 14 | 1.04 (0.48–2.26) |

| 4–6 | 2,303 | 8 | 1.31 (1.07–1.60) | 2,025 | 7 | 1.51 (1.16–1.97) | 613 | 12 | 0.91 (0.66–1.28) | 156 | 21 | 1.67 (0.74–3.76) |

| Intend to quit | ||||||||||||

| No | 2,126 | 8 | Ref | 1,835 | 6 | Ref | 543 | 10 | Ref | 138 | 13 | Ref |

| Yes | 4,855 | 8 | 0.86 (0.74–1.00) | 4,305 | 6 | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 1,215 | 13 | 1.00 (0.75–1.33) | 369 | 17 | 1.40 (0.78–2.52) |

Note. Generalized estimating equation models were used and were adjusted for gender, age group, race/ethnicity, education, income, heaviness of smoking index (HSI), and survey year (see Figure 1 for absolute product use prevalence rates across the survey years); Ns indicate number of unique individuals within rows; percentages consider multiple observations per individual.

aTime frame for product use is within the past month.

bTime frame for product use is within the past year.

cAmong those who reported awareness of the product (i.e., relative use rates).

dTime frame for product use is ever tried.

Table 2 shows the percentages of other smoked tobacco product users, smokeless tobacco product users, and unconventional cigarette users who used each product for each of three given reasons, by demographic characteristics (e-cigarette users were not evaluated due to small sample sizes). A majority of smokeless tobacco users (53%) reported that they used this product to cut down on the amount they smoke, and this was particularly true of minorities, those with low educations, and those with low incomes. While only one fourth of other smoked tobacco product users reported that they used these products to cut down on the amount smoked, this reason was also most common among those with low educations or low incomes. Approximately one third of unconventional cigarette users reported that they used this product for each of the following reasons: as an alternative to quitting, to cut down on the amount smoked, or to help them quit, and endorsing each of these reasons was particularly common among women.

Table 2.

Predictors of Use of Other Smoked Tobacco Products (OSTP), Smokeless Tobacco Products (SLTP), and Unconventional Cigarettes (UC) as an Alternative to Quitting, for Cutting Down on the Amount of Cigarettes Smoked, and for Helping to Quit Conventional Cigarette Smoking

| Predictors | Alternative to quitting | Cut down on cigarettes | To help quita | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSTP | SLTP | UC | OSTP | SLTP | UC | SLTP | UC | |||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Overall | 588 | 18 | 359 | 38 | 290 | 31 | 609 | 26 | 447 | 53 | 291 | 36 | 144 | 43 | 136 | 38 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Female | 196 | 18 | 75 | 43 | 145 | 39*** | 200 | 25 | 91 | 47 | 146 | 43 | 38 | 48 | 71 | 49 |

| Male | 392 | 18 | 284 | 37 | 145 | 22 | 409 | 27 | 356 | 54 | 145 | 27* | 106 | 41 | 65 | 26* |

| Age group | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 98 | 18 | 94 | 35 | 39 | 19 | 105 | 25 | 126 | 44 | 39 | 24 | 37 | 37 | 24 | 23 |

| 25–39 | 150 | 19 | 118 | 37 | 68 | 25 | 155 | 28 | 151 | 56* | 68 | 29 | 50 | 42 | 36 | 31 |

| 40–54 | 246 | 19 | 110 | 46 | 115 | 39 | 252 | 26 | 126 | 59* | 116 | 46 | 42 | 50 | 52 | 52 |

| 55+ | 94 | 13 | 37 | 30 | 68 | 30 | 97 | 25 | 44 | 48 | 68 | 31 | 15 | 38 | 24 | 34 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 473 | 17 | 315 | 38 | 252 | 30 | 487 | 25 | 388 | 52 | 253 | 35 | 123 | 42 | 117 | 37 |

| Other | 115 | 21 | 44 | 42 | 38 | 34 | 122 | 33 | 59 | 61* | 38 | 37 | 21 | 46 | 19 | 45 |

| Education | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 218 | 21 | 183 | 42 | 108 | 34 | 226 | 28 | 220 | 58 | 109 | 34 | 76 | 43 | 49 | 34 |

| Moderate | 251 | 18 | 134 | 37 | 134 | 32 | 261 | 28 | 182 | 51 | 134 | 38 | 55 | 41 | 65 | 43 |

| High | 124 | 14 | 46 | 30 | 48 | 19 | 127 | 20* | 50 | 38* | 48 | 31 | 14 | 47 | 22 | 33 |

| Income | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 196 | 21 | 113 | 46 | 105 | 33 | 206 | 34 | 149 | 60 | 106 | 40 | 44 | 51 | 45 | 45 |

| Moderate | 185 | 18 | 124 | 33 | 83 | 24 | 192 | 25* | 148 | 54 | 84 | 32 | 46 | 38 | 41 | 38 |

| High | 179 | 14 | 111 | 37 | 88 | 36 | 182 | 20** | 136 | 47** | 88 | 35 | 46 | 40 | 48 | 33 |

| Not provided | 44 | 23 | 31 | 34 | 19 | 21 | 47 | 27 | 34 | 38* | 19 | 32 | 14 | 43 | 5 | 40 |

| Heaviness of smoking index | ||||||||||||||||

| 0–1 | 140 | 23 | 74 | 36 | 63 | 32 | 145 | 29 | 90 | 50 | 63 | 32 | 32 | 43 | 41 | 34 |

| 2–3 | 289 | 16 | 185 | 41 | 135 | 34 | 299 | 26 | 217 | 52 | 135 | 39 | 77 | 46 | 59 | 46 |

| 4–6 | 208 | 16 | 130 | 36 | 101 | 26 | 217 | 26 | 178 | 55 | 103 | 34 | 47 | 38 | 43 | 32 |

Note. Generalized estimating equation models were used; Ns indicate number of unique individuals within rows; percentages consider multiple observations per individual.

aAmong those who reported making a quit attempt.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 for odds ratio comparing each category of a variable to the first category of the variable (within columns).

Table 3 shows the associations between unconventional tobacco product use (absolute use rates) and making a quit attempt, successful cessation among those who made a quit attempt in which the user group included all users, and successful cessation among those who made a quit attempt in which the user group only included those who used the product for the purpose of quitting smoking. There was a nonsignificant positive association between use of smokeless tobacco products or unconventional cigarettes and making an attempt to quit smoking conventional cigarettes. However, product users were less likely to succeed in quitting smoking than were nonusers.

Table 3.

Associations Between Use of Unconventional Tobacco Products and Cigarette Quitting Activity

| Type of product | Making a quit attempt | Cessationa | Cessationa,b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % Attempt | OR (95% CI) | N | % Quit | OR (95% CI) | N | % Quit | OR (95% CI) | |

| Other smoked tobacco | |||||||||

| Nonuser | 3,461 | 39 | Ref | 1,693 | 23 | Ref | |||

| User | 414 | 40 | 1.00 (0.84–1.20) | 156 | 17 | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) | |||

| Smokeless tobacco | |||||||||

| Nonuser | 3,498 | 39 | Ref | 1,723 | 22 | Ref | 1,723 | 22 | Ref |

| User | 125 | 45 | 1.25 (0.98–1.58) | 85 | 16 | 0.57 (0.33–0.98) | 45 | 18 | 0.77 (0.37–1.60) |

| Unconventional cigarettes | |||||||||

| Nonuser | 3,367 | 38 | Ref | 1,746 | 23 | Ref | 1,746 | 23 | Ref |

| User | 159 | 48 | 1.27 (0.95–1.69) | 76 | 9 | 0.33 (0.16–0.68) | 46 | 11 | 0.47 (0.21–1.07) |

Note. Generalized estimating equation models were used and were adjusted for gender, age group, race/ethnicity, education, income, heaviness of smoking index, and survey year; analyses used absolute use rates (i.e., the nonuser groups were not limited to those who reported product awareness); Ns indicate number of unique individuals within rows; percentages consider multiple observations per individual.

aAnalyses were limited to those who attempted to quit cigarette smoking.

bUser group was limited to those who used the product for the purpose of quitting cigarette smoking.

DISCUSSION

Among current smokers of conventional cigarettes, we found low reported use of other tobacco products such as cigars, pipe tobacco, and unconventional cigarettes promoted as lower exposure cigarettes. The exception to this finding was the reported use of e-cigarettes and use of smokeless tobacco, the use of which began to rise in 2011. The increased reported use of smokeless tobacco products and the use rate of e-cigarettes at the end of the study period corresponds to increased marketing of these products and the promotion of them as an alternative to cigarette smoking in places where smoking is not allowed. We found that smokers aged 18–24 years were more likely to use each family of unconventional tobacco products compared with older smokers, which is consistent with previous research (Bombard et al., 2007; Bombard et al., 2008; Richardson et al., 2012; Schuster et al., 2012; Tomar, 2010; Wetter et al., 2002).

Interestingly, we found that those with lower incomes were more likely to use other smoked tobacco products or smokeless tobacco products for the purpose of cutting down on conventional cigarettes than were those with higher incomes. Since smokeless tobacco products and many types of cigars are much less expensive than conventional cigarettes, it is possible that smokers use these cheaper products to supplement their cigarettes in order to reduce the cost of continued smoking. Further research is needed to examine the role of cost in use of unconventional tobacco products.

Importantly, despite perceptions of harm reduction among users of unconventional tobacco products, and despite cigarette smokers’ reported use of these products to help them quit smoking, we found no cessation benefit of unconventional tobacco product use and possibly a detrimental effect among users of unconventional cigarettes. These findings are consistent with those from Popova and Ling (2013), who reported that loose leaf, moist snuff, snus, dissolvables, and e-cigarettes did not facilitate successful quit attempts.

Our findings should be considered in light of the following study limitations: Survey response rates ranged from 21% to 35%; however, prior analyses have shown that respondent characteristics correspond well to characteristics of responders to national benchmark surveys, suggesting that any nonresponse to this survey is comparable with that of benchmark surveys (ITC Wave 1 Technical Report, 2004). Also, while approximately 25% of participants were lost to follow-up each year (average number of surveys completed per respondent is two), new respondents were recruited and multivariate analyses were adjusted for characteristics that varied with respect to retention. Additionally, the time frames for unconventional tobacco product use differed among the various types of products, meaning that comparisons across products are not parallel. Also, since the survey did not include an open-ended question regarding reasons for using other products, we could only assess how respondents differ from each other in endorsing the reasons given. Further, the relatively low rate of use of unconventional tobacco products necessarily limits statistical power to evaluate the associations of use or to evaluate nuances involved in use of two or more other tobacco products (i.e., poly product use). We found that less than 2% of cigarette smokers reported using more than one family of other tobacco products, making our population unsuitable for evaluating differences between dual users and poly users. Lastly, evaluating smoking cessation using a retrospective survey design may produce biased estimates if there are differences in recall of unsuccessful quit attempts between unconventional tobacco product users and nonusers (Borland, Partos, & Cummings, 2012). Also, the choice to use an unconventional tobacco product may be confounded by difficulty with quitting. The observational nature of the data collection may create unmeasured bias; however, the prospective data collection method employed for the ITC surveys and the use of multiple adjustments are strengths.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past decade, fewer than 15% of cigarette smokers reported also using unconventional tobacco products although use of e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco increased slightly between 2009 and 2011, consistent with increased marketing of these products. For each type of unconventional tobacco product evaluated, use was most prevalent among those aged 18–24 years. Those who did report using these unconventional tobacco products were no more likely to stop using conventional cigarettes compared with those who did not use such products. These findings suggest that so long as conventional cigarettes remain relatively inexpensive, accessible, and efficient in terms of nicotine delivery, the majority of smokers are likely to continue smoking their conventional product rather than switch to an unconventional product.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table can be found online at http://www.ntr.oxfordjournals.org

FUNDING

This study was supported by Federal funds from the National Institute on Drug Abuse , National Institutes of Health, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN271201100027C. The ITC Four Country Survey has been funded by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (P50 CA111326, P01 CA138389, R01 CA100362, R01 CA125116), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (57897, 79551, and 115016), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903, 450110, and 1005922), Cancer Research UK (C312/A3726, C312/A6465, and C312/A11039), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), and Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (014578). Geoffrey T. Fong is supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. The roles of Wilson Compton, Nicolette Borek, and Anna Kettermann on this article are solely as collaborators on HHSN271201100027C, with no involvement in any other cited projects.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

RJO has served as a consultant to the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (Tobacco Constituents Subcommittee) of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. KMC has received grant support from Pfizer Corporation to develop hospital based tobacco cessation services and has served as a paid expert witness in litigation against the cigarette industry which has on occasion included testimony about the use of other tobacco products by cigarette smokers. WC has minimal (less than $15,000 total value) stock holdings in Pfizer Corporation. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Adkison S. E., O’Connor R. J., Bansal-Travers M., Hyland A., Borland R., Yong H-H., Fong G. T. (2013). Electronic nicotine delivery systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44, 207–215. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombard J. M., Pederson L. L., Nelson D. E., Malarcher A. M. (2007). Are smokers only using cigarettes? Exploring current polytobacco use among an adult population. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2411–2419. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombard J. M., Rock V. J., Pederson L. L., Asman K. J. (2008). Monitoring polytobacco use among adolescents: Do cigarette smokers use other forms of tobacco? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10, 1581–1589. 10.1080/14622200802412887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R., Partos T. R., Cummings K. M. (2012). Systematic biases in cross-sectional community studies may underestimate the effectiveness of stop-smoking medications. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 14, 1483–1487. 10.1093/ntr/nts002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J., Borland R., Yong H. -H., McNeill A., Murray R. L., O’Connor R. J., Cummings K. M. (2010). To what extent do smokers make spontaneous quit attempts and what are the implications for smoking cessation maintenance? Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(Suppl. 1), S51–S57. 10.1093/ntr/ntq052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen J., Mowery P., Delnevo C., Allen J. A., Sokol N., Byron M. J., Thornton-Bullock A. (2011). Seven-year patterns in US cigar use epidemiology among young adults aged 18–25 years: A focus on race/ethnicity and brand. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 1955–1962. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delnevo C. D. (2006). Smokers’ choice: What explains the steady growth of cigar use in the U.S.? Public Health Report, 121, 116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter J. -F. (2010). Electronic cigarettes: A survey of users. BMC Public Health, 10, 231. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter J. -F., Bullen C. (2011). Electronic cigarette: Users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction, 106, 2017–2028. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Register 163. (2013). “Tobacco Products” Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Vol 7, No. 130, p. 40061–40062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong G. T., Cummings K. M., Borland R., Hastings G., Hyland A. J., Giovino G. A., Thompson M. E. (2006). The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tobacco Control, 15(Suppl. III), iii3–iii11. 10.1136/tc.2005.015438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furberg H., Bulik C. M., Lerman C., Lichtenstein P., Pedersen N. L., Sullivan P. F. (2005). Is Swedish snus associated with smoking initiation or smoking cessation? Tobacco Control, 14, 422–424. .org/10.1136/tc.2005.012476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilljam H., Galanti M. R. (2003). Role of snus (oral moist snuff) in smoking cessation and smoking reduction in Sweden. Addiction, 98, 1183–1189. .org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz M. L., Knysak J., Gawron M., Kosmider L., Sobczak A., Kurek J., Benowitz N. (2013). Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tobacco Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012–050859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J. W., Hilbe J. M. (2002). Generalized estimating equations. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC. 10.1201/9781420035285 [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D. K., Ebbert J. O., Feuer R. M., Stepanov I., Hecht S. S. (2007). Changing smokeless tobacco products: New tobacco-delivery systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, S368–S378. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D. K., Slade J., Benowitz N. L., Giovino G. A., Gritz E. R., Leischow S., Warner K. E. (2002). Reducing tobacco harm: Research challenges and issues. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 4(Suppl. 2), S89–S101. 10.1080/1462220021000032852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T. F., Kozlowski L. T., Frecker R. C., Rickert W., Robinson J. (1989). Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Addiction, 84, 791–800. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. R., Keely J. P., Callas P. W. (2005). Ever users versus never users of a “less risky” cigarette. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19, 439–442. 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project (2012). Surveys. Retrieved 17 February, 2012, from http://www.itcproject.org/ (archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65Wm59nLc).

- ITC Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project. (2004). Wave 1 Technical Report Retrieved 17 February, 2012, from http://www.itcproject.org/documents/keyfindings/technicalreports/itcw1techreportfinalpdf (archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65WlnsWWy).

- ITC Policy Evaluation Survey, Four Country Project. (2011). Waves 2 – 8 Technical Report Retrieved 17 February, 2012, from http://www.itcproject.org/documents/keyfindings/4cw28techreportmay2011_2_pdf (archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/65WmeqN1E).

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). (2012). Scientific standards for studies on modified risk tobacco products. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. T., Mumford E. A., Cummings K. M., Gilpin E. A., Giovino G., Hyland A., . . ., Warner K. E. (2004). The relative risks of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product compared with smoking cigarettes: Estimates of a panel of experts. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 13, 2035–2042 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D. T., Mumford E. A., Cummings K. M., Gilpin E. A., Giovino G., Hyland A., . . ., Compton C. (2006). The potential impact of a low-nitrosamine smokeless tobacco product on cigarette smoking in the United States: Estimates of a panel of experts. Addictive Behaviors, 31, 1190–1200. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K. Y., Zeger S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73, 13–22. 10.2307/2336267 [Google Scholar]

- McAuley T. R., Hopke P. K., Zhao J. (2012). Comparison of the effects of e-cigarette vapor and cigarette smoke on indoor air quality. Inhalation Toxicology, 24, 850–857. 10.3109/08958378.2012.724728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor R. J. (2012). Non-cigarette tobacco products: What have we learnt and where are we headed?Tobacco Control, 21, 181–190. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. L., Richardson A., Niaura R. S., Vallone D. M., Abrams D. B. (2012). E-cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1758–1766. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P., Fagan P., Little M. A., Kawamoto C. T., Herzog T. A. (2013). Smokers who try e-cigarettes to quit smoking: Findings from a multiethnic study in Hawaii. American Journal of Public Health, 103, e57–e62. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova L., Ling P. M. (2013). Alternative tobacco product use and smoking cessation: A national study. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 923–930. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramström L. M., Foulds J. (2006). Role of snus in initiation and cessation of tobacco smoking in Sweden. Tobacco Control, 15, 210–214. 10.1136/tc.2005.014969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan A. K., Promoff G., Dube S. R., Arrazola R. (2013). Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tobacco Control, 22, 19–23. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011–050044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A., Xiao H., Vallone D. M. (2012). Primary and dual users of cigars and cigarettes: Profiles, tobacco use patterns and relevance to policy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14, 927–932. 10.1093/ntr/ntr306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians. (2007). Harm reduction in nicotine addiction: Helping people who can’t quit. A report by the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. London: RCP [Google Scholar]

- Schuster R. M., Hertel A. W., Mermelstein R. (2012). Cigar, cigarillo, and little cigar use among current cigarette-smoking adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 925–931. 10.1093/ntr/nts222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Gitchell J. G., Warner K. E., Slade J., Henningfield J. E., Pinney J. M. (2002). Tobacco harm reduction: Conceptual structure and nomenclature for analysis and research. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 4(Suppl. 2, S113–S129. 10.1080/1462220021000032717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Pillitteri J. L., Burton S. L., Di Marino M. E. (2004). Smoker and ex-smoker reactions to cigarettes claiming reduced risk. Tobacco Control, 13, 78–84. 10.1136/tc.2003.005272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2009). Stata Statistical Software: Release 11: College Station, TX: StataCorp LP [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M. E., Fong G. T., Hammond D., Boudreau C., Driezen P., Hyland A., Laux F. L. (2006). Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control, 15(Suppl. III), iii12–iii18. 10.1136/tc.2005.013870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar S. L. (2002). Snuff use and smoking in U.S. men: Implications for harm reduction. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 143–149. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00491-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar S. L., Alpert H. R., Connolly G. N. (2010). Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among US males: Findings from national surveys. Tobacco Control, 19,104–109. 10.1136/tc.2009.031070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickerman K. A., Carpenter K. M., Altman T., Nash C. M., Zbikowski S. M. (2013). Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 1787–1791. 10.1093/ntr/ntt061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (in press). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. Geneva: WHO.

- Wetter D. W., McClure J. B., de Moor C., Cofta-Gunn L., Cummings S., Cinciripini P.M., Gritz E.R. (2002). Concomitant use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco: Prevalence, correlates, and predictors of tobacco cessation. Preventive Medicine, 34, 638–648. 10.1006/pmed.2002.1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S. -H., Wang B., Hartman A., Zhuang Y., Gamst A., Gibson J. T., Galanti M. R. (2009). Quitting cigarettes completely or switching to smokeless tobacco: Do US data replicate the Swedish results? Tobacco Control, 18, 82–87. 10.1136/tc.2008.028209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.