Abstract

Objectives:

This study seeks to investigate to what extent are students conversant with global oral health initiatives and policies, students’ willingness to volunteer service at international setting or developing countries and the need for global oral health course in Nigeria.

Methods:

Final year dental students in two Nigerian Universities were surveyed for this study. The students voluntarily completed the global oral health information questionnaire in a classroom before a scheduled lecture. The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistic 20.

Results:

All the final year students participated in the survey. All the students agreed that they need to be taught course on global oral health and would consider volunteering their dental skills and expertise in an international setting or developing country. Only 4.5% of the students knew the meaning of the basic package of oral care (BPOC) and none of the surveyed students could correctly name the three components of BPOC. Whereas only 18.2% could identify World Dental Federation and World Health Organization as the bodies that developed global oral health goals for the year 2000, none of the students could correctly list the three components of global oral health goals for the year 2000.

Conclusion:

This study concludes that a gap exists in the knowledge of students on global oral health matters and recommends that the curricula of schools be constantly reviewed in line with current trends in policies and practices.

Keywords: Basic package of oral care, dental curriculum, dental volunteer, global oral health, oral health initiatives

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is an important component of general health and a determinant factor for quality of life. Globally major oral health inequalities exist both within and between countries in terms of disease severity and prevalence.[1] Throughout the world, individuals particularly the poor and socially disadvantaged in developing countries, suffer greatly from oral disease.[2] The common oral diseases faced by these groups range from periodontal disease, gingivitis, caries, tooth wear lesions to oral cancer and human immunodeficiency virus-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related oral conditions.[2,3,4] The effect of poor oral health is enormous, besides its impact on general health; the psychosocial effects include poor feeding, aesthetic problems, social embarrassment and isolation and time lost from work or school.[5] The burden of oral disease may be linked to any of these factors including poverty, illiteracy, poor oral hygiene, lack of oral health education and lack of access to prompt and affordable health services.[6] Others factors that may contribute to the burden of the disease include weak or nonexistent national oral health programs, inequitable distribution of dental professionals between urban and rural areas and poorly manage public dental health facilities with inadequate dental materials, instruments and equipment.[5,7,8,9]

In view of the burden of oral diseases, there has been a strong international aid response to public health emergencies and oral health disparities in developing countries.[10,11] Many of the dental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and volunteers have contributed to remedying global oral health disparities.[12,13] The activities of these groups included service provision, education and training, technical assistance and community development. The major limitations were inadequate services and non-sustainability.[14]

Basic package of oral care (BPOC) is a global initiative developed by World Health Organization (WHO) to promote oral health and bridge the gap of oral health inequalities. It can be done with hand instruments using locally trained health workers and the global effort to improve the oral condition of the underserved population could be enhanced if the principle of BPOC is adopted and advocated by dental health care personnel.[15,16]

The importance of oral health goals was first emphasized in 1981 by WHO as part of the program; health for all by the year 2000. In 1982, World Dental Federation (FDI) and WHO developed the global goal for oral health for the year 2000. About a decade ago WHO, jointly with the FDI and the International Association for Dental Research (IADR), formulated goals for oral health by the year 2020. These specific goals may assist in the development of effective oral health programs, targeted to improve the health of those people most in need of care.[10,17,18]

Again, the world oral day introduced in 2007 by FDI provide an occasion for global, regional and national actions and activities on Oral health. It raises awareness and supports improvement in oral healthy by offering dental and oral health community a platform to take action and help reduce the global disease burden.

Undergraduate and graduate students may be exposed to these global initiatives and goals through the teaching of global oral health course. While global oral health course is being taught in some developed countries of the world, none of the dental institutions in Nigeria with the highest number of dental school in the West African sub region is running course on global oral health. The study therefore, seeks to investigate to what extent are students conversant with global oral health issues and the need for global oral health course in Nigerian dental schools.

METHODS

Survey was conducted using final year dental students at the Universities of Port Harcourt and Benin Dental Schools. The global oral health information questionnaire (GOHIQ) was used to collect information from the students. GOHIQ consist of 5 sets of questions[15] and was modified to 10 in this study to broaden the scope. The first three questions were structured and the others were open-ended. The additional questions include; meaning of BPOC, state three components of global goals for oral health 2000, who developed the goal, do you think you need to be taught global oral health course and the world dental body whose mandate is to promote dental and oral health research. The students completed and returned the questionnaires in a classroom before the commencement of a scheduled lecture. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 20.

RESULTS

All the final year students (44) participated in the survey, 14 (31.8%) from University A and 30 (68.2%) from University B. All the students stated they would consider volunteering their dental skills and expertise as a senior dental student or future dentist in an international setting or developing country and agreed that they need to be taught course on global oral health.

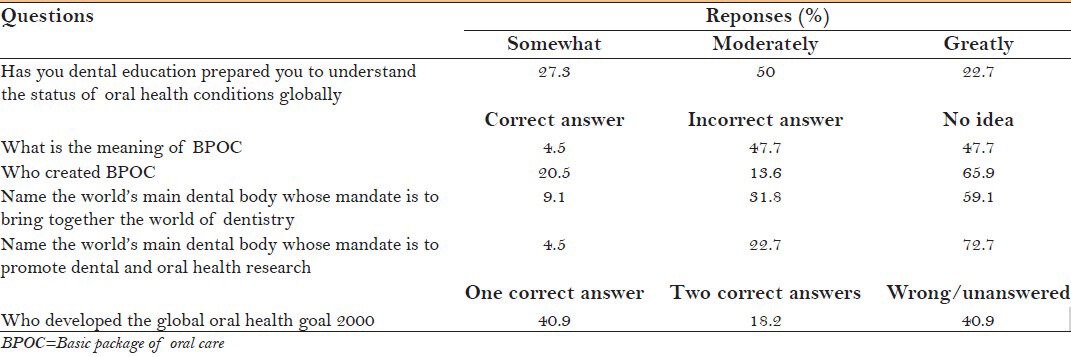

Half of the surveyed students stated that their dental education has “moderately” prepared them to understand the status of oral health conditions globally, especially in developing countries. Nearly 27.3% of the surveyed students stated that they were “somewhat” prepared and 22.7% percent stated that they were “greatly” prepared by their dental education to understand the status of oral health conditions globally.

Only 4.5% of the students (two) knew the meaning of BPOC, the meaning was wrongly defined by 47.7% of the surveyed students and another 47.7% did not know the meaning and left the question unanswered by simply putting a dash. Few students (20.5%) knew who created BPOC. Majority of the students (79.5%) either did not know who created BPOC or gave a wrong answer to the question. None of the surveyed students correctly answer the question “name the three components of BPOC.” Whereas some of the students gave wrong answers, the others left the space blank.

Very few (9%) of the surveyed students could correctly identify FDI as the world dental body whose mandate is to “bring together the world of dentistry, represent the dental profession of the world and stimulate and facilitate the exchange of information across all borders with the aim of optimal oral health for all people,” 4.5% (two) correctly identify IADR as the world dental body whose mandate is to promote dental and oral health research.

None of the students correctly answered the question “list three components of global oral health goals for the year 2000.” Again, while some of the students gave wrong answers the others left the space blank. Only 18.2% identify FDI and WHO as the bodies that developed global oral health goals for the year 2000. While 40.9% identify either FDI or WHO as the body, another 40.9% could not correctly answer the question. These results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Students response to global oral health information questionnaire

DISCUSSION

The Nigerian population is greatly underserved.[15] The delivery of health care services in any country is dependent on a trained cadre of health care professionals. Globally, there is a shortage of health care providers, including oral health care providers, this impact disproportionately on emerging economies and the least developed countries. The needs of developing countries in the oral health care sector are enormous but, have limited capacity to educate and support the workforce needed to meet these needs. This is made worse with serious resource constraints and as well as an immense burden of disease.[18]

There is a growing consensus within the dental profession that its members must advocate and champion collective professional and moral responsibilities to serve the public good by providing expert care to all in need.[19,20] Despite this discussion on dental professionalism and the moral responsibilities of dental practitioners, community service is not a formally recognized competency in dental practice.[21] Dental education has focused mainly on restorative clinical approaches to the detriment of prevention of oral disease in communities or vulnerable populations. Therefore it is an unrealistic expectation for a dental professional to consciously provide care for the underserved populations when formal dental training largely promotes principles of care that are to the contrary.[15] In the present study, conducted in two Nigerian Universities, all the students agreed on the need for global oral health course in Nigerian Universities. This is similar to a study conducted in Central Indian where 96.6% of dental students affirmed the need for global oral health course.[22] A study done by Karim et al.[15] suggested creating a global oral health course that includes the principles of primary oral health care (POHC) and BPOC, at all levels could reinforce the concept that care to the underserved is integral to the profession and an ethical responsibility. Essentially, it affords students the opportunity to hear, learn, practice and evaluates for them the value of such care.

Furthermore, all the surveyed students stated that they would consider volunteering their dental skills or expertise as a future dentist in an international setting or developing countries. In Indian and North American studies 87% and 84% of the students respectively, gave similar indication.[15,22] Volunteer services have contributed to remedying global oral health disparities by providing international aid response to public health emergencies and oral health disparities in developing countries.[11,12,13,14] The situation is not different in our environment. NGOs employ the services of volunteer dental health care personnel to provide oral health care services in rural communities, extending service from one community to the other. Services provided include oral health education, minor oral surgeries and scaling and polishing. The major problems faced by these volunteer groups include lack of follow-up for patients who had minor oral surgeries; lack or inadequate financial support, inability to carry out fillings due to lack of equipments and materials, non-sustainability and above all lack of regulation. It has been reported however, that lack of regulation does not however necessarily detract from the value of their contribution.[14]

Almost all (95.5%) the students did not know the meaning of BPOC and less than a quarter knew who created BPOC as WHO. None of the students knew any of the BPOC components. This is similar to what was also seen in India and North America survey.[15,22] The BPOC, which includes oral urgent treatment, affordable fluoride toothpaste (AFT) and atraumatic restorative treatment, can be delivered by locally trained health workers using some basic instruments and can be tailored specifically to meet the needs of a community. It is designed to work with minimum resources for maximum effect and does not require a dental drill or electricity. It is important to quickly point out, BPOC being advocated to provide care for underserved is mainly a downstream intervention with a focus on restorative care. Only one of the three components focuses on prevention AFT, therefore in advocating for BPOC emphasis has to be placed on prevention. However, since it can be operated without drill and electricity it may serve as a major cornerstone for the provision of both upstream and downstream intervention in settings where there is no electricity or inadequate supply of electricity and therefore may address oral health inequalities.

Global goal for oral health by the year 2000 was developed by WHO and FDI as a strategy for the promotion of oral health globally. Less than 10% of the surveyed students knew the role of FDI and IADR on global oral health. Only 18.2% of the surveyed students could correctly identify WHO and FDI as the bodies that developed the global oral health goals, 40.9% identified the body as either WHO or FDI, the other 40.9% did not have any idea.

This study suggests the need for dental schools in Nigeria to develop curriculum on global oral health which needs to be constantly reviewed in line with current trends in policies and practices. Other studies[15,22] have previously recommended same and suggested that area of focus should include but not limited to; international health with emphasis on dental health organizations such as FDI and IADR, global burden of oral diseases, oral health care delivery systems of established and non-established market economies, global health ethics, the role of NGOs and global dental volunteers and POHC strategies.

By developing global oral health dental curricula in developed and developing countries, global oral health issues and interventions will become recognized and validated as necessary professional responsibilities, not regarded as optional interventions in resource-poor situations.[15] Educating students about global oral health issues includes them in the reality of global oral health disparities and facilitates the belief that they can affect change within and beyond their immediate community.[23,24]

CONCLUSION

The present study revealed that level of awareness on global oral health issues among Nigerian dental students is low. All students expressed a desire to volunteer their professional services in international settings. However, few students knew about the WHO and FDI global goal for oral health as well as the role of IADR and FDI on global oral health. The results suggest that there is a gap between global oral health policy and interventions set out by WHO and FDI and awareness of this policy, interventions and global oral health issues among Nigerian dental students.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marmot M, Bell R. Social determinants and dental health. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:201–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034511402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. Priorities for research for oral health in the 21st century – The approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Health. 2005;22:71–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee R, Sheiham A. The burden of restorative dental treatment for children in Third World countries. Int Dent J. 2002;52:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. World Health Organization. The World Oral Health Report, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auluck A. Oral health of poor people in rural areas of developing countries. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005;71:753–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Palenstein Helderman W, Mikx F, Truin GJ, Hoang TH, Pham HL. Workforce requirements for a primary oral health care system. Int Dent J. 2000;50:371–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helderman WV, Benzian H. Implementation of a basic package of oral care: Towards a reorientation of dental NGOs and their volunteers. Int Dent J. 2006;56:44–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2006.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikx F. Caring for oral needs through the basic package of oral care. Dev Dent. 2003;1:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobdell M, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, Johnson N. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J. 2003;53:285–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benzian H, van Palenstein Helderman W. Dental charity work – Does it really help? Br Dent J. 2006;201:413. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hobdell MH. Taxonomy of volunteering - Humanitarian missions: What they can do and what it involves. Dev Dent. 2003;1:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson M, Dickson GG. Volunteering: Beyond an act of charity. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005;71:865–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benzian H, Gelbier S. Dental aid organisations: Baseline data about their reality today. Int Dent J. 2002;52:309–14. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karim A, Mascarenhas AK, Dharamsi S. A global oral health course: Isn’t it time? J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1238–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frencken JE, Holmgren C, Helderman WH. Basic Package of Oral Care. World Health Organisation. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – The approach of the WHO global oral health programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. World Health Report. 2006. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf .

- 19.Welie JV. Is dentistry a profession? Part 2. The hallmarks of professionalism. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70:599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garetto LP, Yoder KM. Basic oral health needs: A professional priority? J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1166–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Dental Education Association. Competencies for the new general dentist (as approved by the 2008 ADEA House of Delegates) J Dent Educ. 2008;72:823–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh A, Purohit B. Global oral health course: Perception among dental students in central India. Eur J Dent. 2012;6:295–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerr AR, Changrani JG, Gany FM, Cruz GD. An academic dental center grapples with oral cancer disparities: Current collaboration and future opportunities. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:531–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huynh-Vo L, Rosenbloom JM, Aslanyan G, Leake JL. Investigating the potential for students to provide dental services in community settings. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:408–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]