Abstract

Background/Aims

Gallbladder diseases can give rise to dyspeptic or colonic symptoms in addition to biliary pain. Although most biliary pain shows improvement after cholecystectomy, the fates of dyspeptic or colonic symptoms still remain controversial. This study assessed whether nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms improved after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and identified the characteristics of patients who experienced continuing or exacerbated symptoms following surgery.

Methods

Sixty-five patients who underwent LC for uncomplicated gallbladder stones or gallbladder polyps were enrolled. The patients were surveyed on their dyspeptic or colonic symptoms before surgery and again at 3 and 6 months after surgery. Patients' mental sanity was also assessed using a psychological symptom score with the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised questionnaire.

Results

Forty-four (67.7%) patients showed one or more dyspeptic or colonic symptoms before surgery. Among these, 31 (47.7%) and 36 (55.4%) patients showed improvement at 3 and 6 months after surgery, respectively. However, 18.5% of patients showed continuing or exacerbated symptoms at 6 months after surgery. These patients did not differ with respect to gallstone or gallbladder polyps, but differed in frequency of gastritis. These patients reported lower postoperative satisfaction. Patients with abdominal symptoms showed higher psychological symptom scores than others. However, poor mental sanity was not related to the symptom exacerbation.

Conclusions

Elective LC improves dyspeptic or colonic symptoms. Approximately 19% of patients reported continuing or exacerbated symptoms following LC. Detailed history-taking regarding gastritis before surgery can be helpful in predicting patients’ outcome after LC.

Keywords: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; Cholecystectomy, laparoscopic; Gastritis; Postcholecystectomy syndrome

Introduction

The symptoms of gallstones occur in a wide range, from no symptoms to severe abdominal pain.1 In addition to abdominal pain, gallbladder stimulation by gallstones can give rise to gastrointestinal symptoms such as indigestion, nausea, vomiting and food intolerance.2 In almost all patients with gallstones, biliary pain disappears after cholecystectomy.3–5 However, the rates of relief from nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms tend to be low and heterogeneous in patients who undergo an elective cholecystectomy.3

In contrast to patients with gallstones, most patients with gallbladder polyps are asymptomatic. However, a minority of patients report abdominal symptoms that are similar to those induced by small gallstones that are rarely detached from the mucosa.6

When cholecystectomy is recommended, many patients wondered about the relief of their symptoms and about any occurrence of new symptoms after removing the gallbladder. However, many studies have reported that the changes in abdominal symptoms after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) may differ according to the selection of patients and their preoperative conditions. Variable factors were reported as predictors of poor outcomes in many different studies. The presence of gastrointestinal diseases including irritable bowel syndrome7 or bloating,8 rather than the original gallbladder disease, was also related to the persistence of symptoms after cholecystectomy. Patients with psychiatric medication,8 psychological problems,8 personality disorders9 and neuroticism10 showed poor outcomes. Patients with poor outcomes after cholecystectomy also showed decreased compliance, which complicates the effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, a method for predicting outcomes and factors related to poor outcomes is necessary in the clinical setting.

This study was designed to evaluate the outcomes of non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms after LC and to identify the factors attributable to poor outcomes. We compared symptom scores in patients with gallstones, who had typical biliary pain, and in those with gallbladder polyps, who were typically symptom free or experienced only mild abdominal discomfort. We evaluated the effects of psychological factors on the symptom outcome by scoring mental sanity in all patients with the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) questionnaire prior to surgery.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Among 134 patients who received LC at Chungbuk National University Hospital between October 2009 and May 2010. A total 65 patients which include 32 patients with gallstones, 31 patients with gallbladder polyps and 2 patients with both gallstones and gallbladder polyps were enrolled in this study. Two patients with gallstones and gallbladder polyps were included in the gallstone group. All patients experienced relief from abdominal pain at the time of surgery and underwent elective LC. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: 19 who were younger than 15 or older than 65 years of age, 31 with acute cholecystitis, 8 with stenosis or gallstones in the biliary tract, 6 with presence of cancer and 5 with severe comorbidities. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to LC.

Dyspeptic or Colonic Symptoms at Pre- and Post-operation

Interviews were conducted 1 day before surgery to assess medical history and abdominal symptoms. Abdominal symptoms of indigestion, nausea, vomiting, food intolerance, heartburn, acid regurgitation, loss of appetite, diarrhea and constipation were recorded as 0, 1 and 2 for “none,” “weak” and “severe,” respectively. Additionally, simple psychological diagnoses and examinations using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) questionnaire were recorded for all patients to evaluate overall mental health prior to surgery. The SCL-90-R records 0 to 4 points for each item by self-evaluation, with measurements consisting of 90 items. Overall, the global severity index, positive symptom distress index, and positive symptom total were measured. The SCL-90-R used internet scoring (testcenter.co.kr) operated by Test Center Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). Total scores for abdominal symptoms were recorded at 3 and 6 months after surgery through phone interviews and compared with preoperative scores. Patients were determined to have an overall improvement when they remained in an asymptomatic state or showed a decrease in total symptom scores.

Pathologic Evaluation of Cholecystectomized Gallbladder

All gallbladder specimens were sent for histopathology. The presence of chronic cholecystitis, gallbladder wall thickening and adenomatous hyperplasia were analyzed as pathological data. Chronic cholecystitis was diagnosed when the mucosa was infiltrated with mononuclear inflammatory cells and the epithelium showed atrophic, hyperplastic or metaplastic changes. A gall-bladder wall ≥ 3 mm in thickness was defined as thickened. Adenomatous hyperplasia was defined by the presence of hyperplasia of the gallbladder wall, limited to the epithelial elements of the mucosa without the involvement of the muscular layer.11

Statistical Methods

Discrete variables, including symptoms and clinical features, were evaluated using the Chi-square test, while the t test or paired t test was used to assess changes in symptom scores before and after surgery. SCL-90-R results were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test to assess the relationship between patients’ symptoms before and after surgery. P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS software (ver. 12; SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Characteristics of Patients With Gallstones or Gallbladder Polyps

Among the 34 patients with gallstones or 31 patients with gallbladder polyps, no differences were noted for gender, ages, history of abdominal surgery, or history of pancreatitis or hepatitis. Two patients with gallstones were currently using a psychiatric medication. Twelve patients were diagnosed with gastritis by an endoscopic exam less than 2 months before surgery. All but 3 patients with gallbladder polyps had chronic cholecystitis. Gallbladder wall thickening more than 3 mm was detected in 67.6% and 54.8% of patients with gallstones and gallbladder polyps, respectively. Adenomatous hyperplasia was detected in seven patients with gallstones and in one patient with gallbladder polyp. Prior to surgery, all patients’ blood and liver function tests were in normal ranges (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of 65 Patients With Gallbladder Diseases

| Parameters | Gallstones (n = 34) | Gallbladder polyps (n = 31) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male:Female | 16:18 | 19:12 | NS |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 45.0 ± 7.0 | 46.0 ± 6.0 | NS |

| Past medical history (n [%]) | |||

| Abdominal surgery | 11 (32.4) | 11 (35.5) | NS |

| Pancreatitis or hepatitis | 5 (14.7) | 2 (6.5) | NS |

| Psychiatric drugs | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Gastritis | 6 (17.6) | 6 (19.4) | NS |

| Laboratory findings (mean ± SD) | |||

| AST (IU/L) | 22.5 ± 4.5 | 23.6 ± 6.6 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 32.6 ± 18.5 | 23.7 ± 12.9 | 0.030 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 176.2 ± 62.9 | 154.5 ± 66.8 | NS |

| WBC (/mm3) | 6,650 ± 1,388 | 6,319 ± 1,811 | NS |

| Histopathological findings (n [%]) | |||

| Chronic cholecystitis | 34 (100.0) | 28 (90.3) | NS |

| GB wall thicking (≥ 3 mm) | 23 (67.6) | 17 (54.8) | NS |

| Adenomatous hyperplasia | 7 (20.6) | 1 (3.2) | 0.033 |

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; WBC, white blood cell; GB, gallbladder; NS, not significant.

Patients’ Dyspeptic or Colonic Symptoms Before and After Elective Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

One or more abnormalities in abdominal symptoms were recorded in 44 (67.7%) patients, including indigestion (50.8%), nausea (26.2%), heartburn (23%), loss of appetite (21.5%), food intolerance (20%), constipation (18.5%), acid regurgitation (9.2%), diarrhea (7.7%) and vomiting (4.6%) (Table 2). Abdominal symptom score (range, 0–18) before surgery was 1.92. This score decreased to 1.11 and 0.88, at 3 months and 6 months after surgery, respectively (P = 0.006 and P < 0.001 by a paired t test). The number of patients who showed improved symptom scores was 31 (47.7%) and 36 (55.4%) after 3 and 6 months, respectively. Among abdominal symptoms, indigestion, food intolerance, heartburn and constipation were improved after 3 and 6 months. However, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and acid regurgitation did not differ before and after surgery. Diarrhea, which was aggravated 3 months after surgery, was restored to the pre-surgical level at 6 months after surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequencies of Dyspeptic or Colonic Symptoms Before and After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

| Symptoms | Before | 3 months after surgery | 6 months after surgery | P1-value | P2-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absence | 21 (32.3) | 42 (64.6) | 45 (69.2) | - | - |

| Overall symptom scores (mean ± SD) | 1.92 ± 2.11 | 1.11 ± 1.78 | 0.88 ± 1.68 | 0.006a | < 0.001a |

| Indigestion | 0.035 | 0.013 | |||

| None | 32 (49.2) | 46 (70.8) | 50 (76.9) | ||

| Weak | 20 (30.8) | 15 (23.1) | 11 (16.9) | ||

| Severe | 13 (20.0) | 4 (6.1) | 4 (6.2) | ||

| Nausea | NS | NS | |||

| None | 48 (73.8) | 57 (87.7) | 57 (87.7) | ||

| Weak | 15 (23.1) | 8 (12.3) | 8 (12.3) | ||

| Severe | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Vomiting | NS | NS | |||

| None | 62 (95.4) | 65 (100.0) | 62 (95.4) | ||

| Weak | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.6) | ||

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Food intolerance | 0.006 | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 52 (80) | 51 (78.5) | 55 (84.6) | ||

| Weak | 7 (10.8) | 14 (21.5) | 8 (12.3) | ||

| Severe | 6 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | ||

| Heart burn | 0.014 | 0.024 | |||

| None | 50 (76.9) | 55 (84.6) | 57 (87.7) | ||

| Weak | 14 (21.5) | 10 (15.4) | 8 (12.3) | ||

| Severe | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Acid regurgitation | NS | NS | |||

| None | 59 (90.8) | 61 (93.8) | 62 (95.4) | ||

| Weak | 5 (7.7) | 4 (6.2) | 3 (4.6) | ||

| Severe | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Loss of appetite | NS | NS | |||

| None | 51 (78.5) | 54 (83.1) | 61 (93.8) | ||

| Weak | 13 (20.0) | 9 (13.8) | 4 (6.2) | ||

| Severe | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Diarrhea | 0.050 | NS | |||

| None | 60 (92.3) | 51 (80.0) | 59 (86.2) | ||

| Weak | 5 (7.7) | 10 (15.4) | 9 (13.8) | ||

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Constipation | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 53 (81.5) | 56 (86.2) | 57 (87.7) | ||

| Weak | 9 (13.8) | 9 (13.8) | 8 (12.3) | ||

| Severe | 3 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) |

Paired t test.

P1, P-value of before 3 months vs. post 3 months; P2, P-value of before 6 months vs. post 6 months; NS, not significant. Data are presented as n (%).

Relation Between Dyspeptic or Colonic Symptoms and Psychological Symptom Scores

A simple psychiatric test before surgery showed great differences between symptom positive and negative group. Specifically, patients with abdominal symptoms had significantly higher values than patients without symptoms regarding somatization, obsessive-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, and paranoid ideation. Overall group measurements were also higher regarding global severity index, positive symptom distress index, and positive symptom total. However, no differences were noted between the groups for measures of hostility, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Psychological Symptom Scores Between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients Before Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | Symptomatic patients (n = 44) | Asymptomatic patients (n = 21) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatization | 46.9 ± 6.9 | 39.0 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsion | 41.3 ± 8.0 | 36.1 ± 4.7 | < 0.001 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 42.4 ± 8.7 | 36.9 ± 3.3 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 42.4 ± 7.9 | 36.4 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 44.2 ± 7.0 | 40.1 ± 4.6 | 0.015 |

| Hostility | 43.6 ± 6.9 | 40.5 ± 2.2 | 0.060 |

| Phobic anxiety | 45.2 ± 6.8 | 42.1 ± 1.6 | 0.148 |

| Paranoid ideation | 41.8 ± 6.0 | 39.4 ± 3.5 | 0.040 |

| Psychoticism | 42.6 ± 7.2 | 39.8 ± 2.9 | 0.063 |

| Global severity index | 42.3 ± 7.6 | 36.4 ± 3.6 | < 0.001 |

| Positive symptom distress | 46.9 ± 8.7 | 39.9 ± 12.3 | 0.020 |

| Positive symptom total | 39.9 ± 8.2 | 31.4 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD of T score.

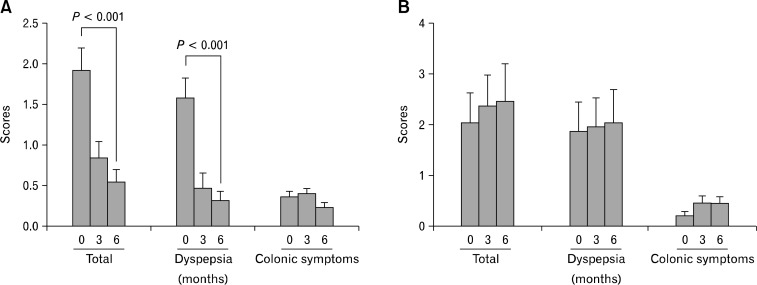

Clinical Features of Patients With Continuing or Exacerbated Symptoms After Surgery

At 6 months after cholecystectomy, 12 of 65 (18.5%) patients had either no improvement or an increased total symptom score compared to before surgery. No difference was noted between improved and unimproved patients in regard to gallstones or gallbladder polyps, gender, age, educational levels, economic conditions, marital status, gallbladder pathology or history of abdominal surgery. However, the patients having gastritis showed poor outcomes (P = 0.007, Table 4). The patients without gastritis showed total symptom scores to be decreased at 3 months and 6 months after LC compared to those at the time of enrollment, especially regarding the dyspeptic symptoms. However, the patients with gastritis did not show improvements of dyspeptic or colonic symptoms (Figure). Patients’ surgical satisfaction differed depending on the degree of symptom improvement after surgery (P < 0.001, Table 4). Only 33.3% of patients with unimproved abdominal symptoms were satisfied with their surgery, while 94.3% of patients with symptom improvement were satisfied. No significant difference was detected in SCL-90-R examination values with respect to the patients’ outcomes (Table 5).

Table 4.

Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Patients With Worsened Abdominal Symptoms at 6 Months After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

| Parameters | n | Improved patients (n = 53) | Unimproved patients (n = 12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 35 | 29 (82.9) | 6 (17.1) | NS |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 65 | 45.8 ± 6.7 | 45.0 ± 6.4 | NS |

| Types of gallbladder diseases | NS | |||

| Gallbladder stones | 34 | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.5) | |

| Gallbladder polyps | 31 | 27 (87.1) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Education status | NS | |||

| Less than college | 43 | 36 (83.7) | 7 (16.3) | |

| University graduates | 22 | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Socioeconomic status | NS | |||

| Less than intermediate | 14 | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Medium or more | 51 | 42 (82.4) | 9 (17.6) | |

| Marriage | NS | |||

| Unmarried | 10 | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Married | 55 | 46 (83.6) | 9 (16.4) | |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Abdominal surgery | 22 | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | NS |

| Pancreatitis or hepatitis | 7 | 7 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Psychiatric treatment | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | NS |

| Gastritis | 12 | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 0.007 |

| Histopathologic findings | ||||

| Chronic cholecystitis | 62 | 51 (82.3) | 11 (17.7) | NS |

| GB wall thicking (≥ 3 mm) | 40 | 33 (82.5) | 7 (17.5) | NS |

| Adenomatous hyperplasia | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | NS |

| Patients’ satisfaction | < 0.001 | |||

| Very satisfied | 38 | 38 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Satisfied | 16 | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Neutral | 10 | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | |

| Dissatisfied | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) |

GB, gallbladder; NS, not significant.

Data are presented as n (%).

Figure.

Changes of symptom scores, total, dyspeptic or colonic symptoms, before surgery and at 3 and 6 months after surgery in patients without gastritis (A) and in those with gastritis (B). Dyspeptic symptoms include indigestion, nausea, vomiting, food intolerance, heart burn, acid regurgitation and loss of appetite. Colonic symptoms represent diarrhea and constipation.

Table 5.

Changes in Psychological Symptom Scores According to Gastrointestinal Symptom Improvement at 6 Months After Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | Improved patients (n = 53) | Unimproved patients (n = 12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatization | 45.3 ± 7.5 | 44.6 ± 5.2 | NS |

| Obsessive-compulsion | 40.2 ± 7.4 | 39.3 ± 9.3 | NS |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 41.6 ± 8.2 | 41.8 ± 8.9 | NS |

| Depression | 42.2 ± 8.0 | 41.1 ± 8.2 | NS |

| Anxiety | 43.2 ± 6.9 | 43.0 ± 6.4 | NS |

| Hostility | 42.9 ± 5.5 | 44.2 ± 10.2 | NS |

| Phobic anxiety | 44.8 ± 6.7 | 44.3 ± 4.6 | NS |

| Paranoid ideation | 41.4 ± 5.5 | 41.8 ± 7.7 | NS |

| Psychoticism | 42.3 ± 7.2 | 42.1 ± 4.9 | NS |

| Global severity index | 41.1 ± 7.4 | 40.9 ± 8.2 | NS |

| Positive symptom distress | 45.2 ± 10.5 | 43.2 ± 12.9 | NS |

| Positive symptom total | 38.3 ± 9.2 | 37.6 ± 7.3 | NS |

NS, not significant.

Data are presented as mean ± SD of T score.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that elective LC improves non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms; the number of patients having abdominal symptoms decreased from 44 (67.7%) before surgery, to 23 (35.4%) and then 20 (30.8%), respectively, at 3 and 6 months after surgery. Scores for symptoms before and after surgery showed the same trend, with the average score of 1.92 before surgery decreasing to 1.11 and 0.88 at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Symptoms were improved in patients with gallstones or gallbladder polyps, regardless of the type of disease.

Previous studies revealed that abdominal symptoms continued in 43–57% even after elective LC in patients with gallstones.2,8,12,13 In contrast, the present study showed a lower rate of continuous symptoms than those of previous studies. The reasons may be that all patients except three had chronic cholecystitis and severe pathologic changes are usually related with a high rate of symptom relief.14 Similar to previous reports,3,8,15,16 our findings showed that indigestion, food intolerance, heartburn, and constipation were improved after surgery. However, nausea, vomiting, and acid regurgitation did not differ before and after surgery. The incidence of diarrhea increased temporarily at 3 months after surgery and then recovered by 6 months. Currently, no studies have reported any variations in symptoms before and after surgery for patients with gallbladder polyps. This study confirmed that more than half of the patients with gallbladder polyps also reported dyspeptic or colonic symptoms before surgery and showed improvements after surgery which is a similar feature presented in patients with gallstones.

Nevertheless, cholecystectomy was not effective in easing the symptoms for every patient, because no symptom improvement or a worsening of symptoms occurred in 12 of 65 (18.5%) patients at 6 months after surgery. Abdominal symptoms may have resulted from diseases in organs other than the gallbladder because many patients with no improvement in symptoms were diagnosed with gastritis before surgery. Sosada et al.17 reported that many symptoms had originated from gastrointestinal tracts and not from the gallbladder. In the present study, twelve patients were diagnosed with gastritis by endoscopy and these patients showed poor outcomes. Other studies revealed that the presence of irritable bowel syndrome7 or bloating8 was also related with persistent symptoms after cholecystectomy.

At present, no obvious correlation can be drawn from the literature regarding psychiatric problems and worsening symptoms after surgery. Previous studies suggested that patients with continuous pain after surgery had increased psychological vulnerability.14,18,19 However, other study reported that psychiatric factors had no special relationship with symptom variation after surgery.11 The current study considered that psychiatric conditions before a surgery did not greatly affect variation in symptoms after surgery, although they showed significant differences when compared with the scores for patients with no symptoms.

Cholecystectomy has been recommended under limited conditions.20,21 Although controversy remains whether cholecystectomy should be performed in gallstone patients with dyspeptic or colonic symptoms, many reports show that atypical symptoms are improved after cholecystectomy in gallstone patients, suggesting the need to offer cholecystectomy to these patients.22 Considering that these studies found chronic cholecystitis in 95% of cases after cholecystectomy, atypical abdominal symptoms are likely to occur as a result of chronic inflammation. However, it is very difficult to identify patients with gallstones or gallbladder polyps for treatment when they report atypical abdominal symptoms, because symptom variation is very subjective. Although the causes of dyspeptic or colonic symptoms in patients with gallbladder polyps or gallstones have not been clarified, the present view is that surgery should be performed when other medical treatments have been tried and after the existence of gastritis is ruled out. In the present study, patient’s satisfaction on surgery differed depending on the degree of symptom improvement after surgery.

Approximately two-thirds of patients who underwent gallbladder surgery showed improvement in their abdominal symptoms irrespective of gallstones or gallbladder polyps. Many patients with no improvement in their symptoms had been diagnosed with gastritis before surgery and their satisfaction with surgery was low. Detailed history-taking regarding gastritis before surgery can be helpful in predicting patients’ outcome after LC.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

References

- 1.Lorusso D, Porcelli P, Pezzolla F, et al. Persistent dyspepsia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The influence of psychological factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:653–658. doi: 10.1080/00365520310002995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finan KR, Leeth RR, Whitley BM, Klapow JC, Hawn MT. Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life after cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger MY, Olde Hartman TC, Bohnen AM. Abdominal symptoms: do they disappear after cholecystectomy? Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1723–1728. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitzer EM, Lorenz C, Nickel S, Dörning H, Trojan A. Assessing patient-reported outcomes of cholecystectomy in short-stay surgery. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2712–2719. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9878-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yun SN, Kim SH, Park SJ, Jang JY, Park YH. Clinical outcome after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 1999;57(suppl):1023–1030. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon W, Jang JY, Lee SE, Hwang DW, Kim SW. Clinicopathologic features of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder and risk factors of gallbladder cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:481–487. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.3.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirk G, Kennedy R, McKie L, Diamond T, Clements B. Preoperative symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome predict poor outcome after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3379–3384. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luman W, Adams WH, Nixon SN, et al. Incidence of persistent symptoms after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study. Gut. 1996;39:863–866. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svebak S, Søndenaa K, Hausken T, Søreide O, Hammar A, Berstad A. The significance of personality in pain from gallbladder stones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:759–764. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jess P, Jess T, Beck H, Bech P. Neuroticism in relation to recovery and persisting pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:550–553. doi: 10.1080/00365529850172151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stokes MC, Burnette R, Ballard B, Ross C, Beech DJ. Adenomatous hyperplasia of the gallbladder. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:959–961. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson RG, Macintyre IM. Symptomatic outcome after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:439–441. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ure BM, Troid lH, Spangenberger W, et al. Long-term results after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:267–270. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon AJ, Ross S, Baxter JN, et al. Symptomatic outcome 1 year after laparoscopic and minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: a randomised trial. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1378–1382. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lublin M, Crawford DL, Hiatt JR, Phillips EH. Symptoms before and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallstones. Am Surg. 2004;70:863–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vignolo MC, Savassi-Rocha PR, Coelho LG, et al. Gastric emptying before and after cholecystectomy in patients with cholecystolithiasis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:850–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sosada K, Zurawinski W, Piecuch J, Stepien T, Makarska J. Gastroduodenoscopy: a routine examination of 2,800 patients before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Enndosc. 2005;19:1103–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-2025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borly L, Anderson IB, Bardram L, et al. Preoperative prediction model of outcome after cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1144–1152. doi: 10.1080/003655299750024968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jørgensen T. Abdominal symptoms and gallstone disease. An epidemiological investigation. Hepatology. 1989;9:856–860. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt M, Dumot JA, Søreide O, Søndenaa K. Diagnosis and management of gallbladder calculus disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1257–1265. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.704934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bang S. [Natural course and treatment strategy of gallbladder polyp.] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:336–340. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.53.6.336. [Korean] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mentes BB, Akin M, Irkörücü O, et al. Gastrointestinal quality of life in patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic gallstones before and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1267–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]