Abstract

Background/Aims

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more important in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients. This study investigated the prevalence of high risk for obstructive sleep apnea in GERD patients in comparison with that in healthy controls using the Berlin Questionnaire. We also investigated the risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in GERD patients.

Methods

We enrolled 1,007 subjects: 776 healthy controls, 115 individuals with erosive reflux disease, and 116 with non-erosive reflux disease. GERD was diagnosed and classified using endoscopy and a reflux questionnaire. The Berlin Questionnaire was used to evaluate obstructive sleep apnea.

Results

More patients in the GERD group (28.2%) had higher risk for obstructive sleep apnea than healthy controls (20.4%, P = 0.036). More patients with non-erosive disease (32.8%) had higher risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) than patients with erosive disease (20.9%) and controls (20.4%, P = 0.010). On multivariate analysis, non-erosive disease was a high risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea (odds ratio [OR], 1.82; P = 0.011). Age ≥ 55 years (OR, 1.83; P < 0.001) and a high body mass index (≥ 25 kg/m2) (OR, 2.76; P < 0.001) were also identified as risk factors. Nocturnal GERD was related to high risk for OSA in non-erosive disease patients (OR, 2.97; P = 0.019), but not in erosive disease patients.

Conclusions

High risk for OSA is more prevalent in GERD patients than in controls. Non-erosive reflux disease, age ≥ 55, and a high BMI are associated with high risk for OSA.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux; Esophagitis; Sleep apnea, obstructive

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a very common disorder worldwide, and is classified into erosive reflux disease (ERD) and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD). In western countries, typical GERD symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation occur in about 20% of adults. In Eastern Asia, the prevalence of GERD has increased gradually and was reported to be around 2.5–4.8% before 2005 but reached to 5.2–8.5% from 2005 to 2010.1

GERD can coexist with variable extraesophageal manifestations such as non-cardiac chest pain, posterior laryngitis, respiratory complications, and sleep disturbance. The association between GERD and sleep disorders is controversial, even though a relationship between GERD and insomnia has been established. More recently, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is found to be an emerging sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by episodes of intermittent, partial, or complete obstruction of the upper airway. It causes transient awakening from sleep during the night.

One published study2 suggested GERD may be associated with OSA, but this is still being debated. Furthermore, in an epidemiologic survey, GERD patients with nocturnal symptoms were found to be at an increased risk of OSA.3 Patients with OSA may have an increased risk of GERD, as evidenced by the frequent findings of gastrointestinal symptoms, esophageal pH monitoring, and endoscopic findings of esophagitis.2,4

Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the prevalence of high risk for OSA in patients with GERD and that in healthy controls to evaluate if there is an association between GERD and OSA. For this, we used the Berlin Questionnaire, a convenient and inexpensive tool, which has been widely used in the screening for the clinical evaluation of OSA.5 In addition, risk factors for OSA in GERD subjects were investigated.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

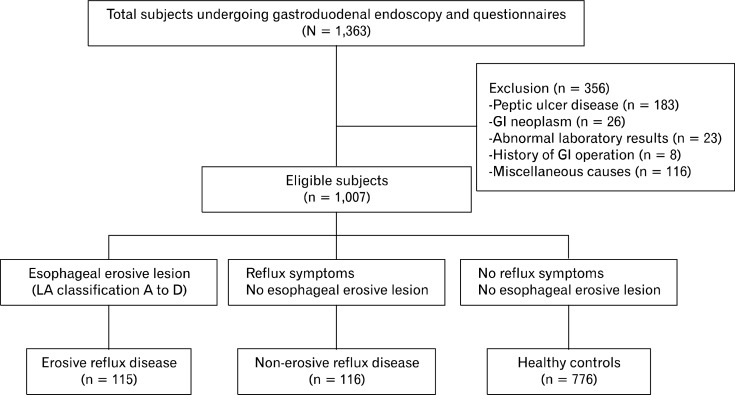

We enrolled 1,363 subjects who visited the gastrointestinal clinic and the health promotion center of St. Paul’s Hospital of The Catholic University of Korea between March and October in 2009. Trained and certified clinicians performed the standard gastroduodenal endoscopic examination in all patients. Subsequently, all patients completed questionnaires for the evaluation of GERD and the Berlin questionnaire for OSA. We excluded 356 subjects who had a history of gastrointestinal surgery, peptic ulcer disease, gastroduodenal neoplasm, or other chronic systemic diseases requiring medical therapy. Peptic ulcer disease was observed in 183 patients, gastroduodenal neoplasm in 26 patients, and abnormal laboratory findings were reported in 23 patients. Eight patients were excluded because they had a history of gastrointestinal surgery, and the others were excluded for various miscellaneous reasons, including the presence of other medical disease or psychiatric disorders. Finally, 1,007 subjects were included in this study (Fig. 1). All subjects in the control group were participants from the health promotion center, while the subjects in the GERD group included all patients from the gastrointestinal clinic and a few participants from the health promotion center. The subjects of control group had no specific gastrointestinal symptoms and received endoscopic examination for screening. Using a questionnaire, we excluded participants with typical reflux symptoms from the control group. The study was approved by the institutional review board at our hospital (PC09ZZZZ0060).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the protocol used to classify subjects in this study.

Questionnaires

The reflux questionnaire has been designed to investigate a patient’s gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and socio-demographic data and was completed by each subject. The questionnaire used was originally designed by the Mayo clinic for an epidemiological study and was then adapted for our study.6–9 The subjects were asked to respond to questions regarding the weekly frequency of typical reflux symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation and to rate them on a scale of 1–5: (0) none, (1) less than once a month, (2) approximately once a month, (3) approximately once a week, (4) more than twice a week and (5) every day.

The Berlin questionnaire (BQ) has been validated as a tool for identifying patients who are at high risk for OSA with variations designed for different countries.10,11 The BQ includes 10 questions in 3 categories: 5 items about snoring severity in category 1, 4 items about wake-time sleepiness and tiredness in category 2 and history of hypertension or obesity in category 3.12 Category 1 and 2 are positive when the total score reaches 2 points or more and category 3 is positive if the subject has a history of high blood pressure and/or BMI of more than 30 kg/m2. High risk for OSA is defined as 2 or more positive categories, while low risk for OSA is defined as only one or none of the positive categories. All questionnaires were completed before diagnostic evaluation and administered by trained and certified staff.

Disease Classification

We described endoscopic findings for GERD according to the Los Angeles (LA) classification of esophagitis.13 ERD was defined as endoscopy findings indicating mucosal breaks at the gastroesophageal junction, classified as from A to D according to the LA classification. Patients who showed minimal change were excluded from the ERD group. The NERD group included patients who experienced typical GERD symptoms such as heart-burn or acid regurgitation for more than once a week but did not experience erosive esophagitis. If a patient had symptoms but had minimal change at the gastroesophageal junction, then the patient was excluded from the ERD group and included in the NERD group. Controls had no GERD symptoms with normal endoscopic findings.

Statistical Methods

Patient’s categorical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate categorical variables. A t test was used to evaluate continuous variables. Differences between GERD and controls were assessed using the Chi square test and t tests. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to investigate risk factors for OSA (SAS system for Windows, version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The level of statistical significance was P < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 1,007 subjects were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of all subjects are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There were no differences in age (55.1 ± 9.1 vs. 54.9 ± 8.8, P = 0.767), sex (male, 43.3% vs. 38.3%, P = 0.166), body mass index (BMI) (≥ 25 kg/m2, 31.6% vs. 30.9%, P = 0.501) and smoking history (13.1% vs. 10.9%, P = 0.346) between GERD and control groups (Table 1). Patients were categorized into 3 groups according to GERD symptoms and endoscopic findings: 115 individuals into ERD group (LA classification A to D in endoscopic examination), 116 individuals into NERD group (GERD symptoms and normal or minimal change on endoscopy), and 776 individuals into the control group. There were no significant differences in age among the 3 groups. The proportion of women was higher in the NERD and control groups, whereas the proportion of men was higher in the ERD group (P < 0.001). No significant differences in BMI were found among 3 groups (BMI ≥ 25, 27.6% in NERD group vs. 35.7% in ERD group vs. 30.9% in the control group, P = 0.373).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Subjects

| GERD (n = 231) | Controls (n = 776) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 55.1 ± 9.1 | 54.9 ± 8.8 | 0.767 |

| Sex (n [%]) | 0.166 | ||

| Male | 100 (43.3) | 297 (38.3) | |

| Female | 131 (56.7) | 479 (61.7) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 23.9 ± 2.8 | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 0.501 |

| < 25 | 158 (68.4) | 536 (69.1) | |

| ≥ 25 | 73 (31.6) | 240 (30.9) | |

| Cigarette smoking (n [%]) | 30 (13.1) | 84 (10.9) | 0.346 |

| Alcohol consumption (n [%]) | 119 (52.2) | 339 (43.9) | 0.026 |

| Nocturnal GERD (n [%]) | 54 (23.4) | 32 (4.1) | <0.001 |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics in Patients With Non-erosive Reflux Disease, Erosive Reflux Disease and Controls

| NERD (n = 116) | ERD (n = 115) | Controls (n = 776) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 55.8 ± 8.4 | 54.2 ± 9.8 | 54.9 ± 8.8 | 0.384 |

| Sex (n [%]) | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 27 (23.3) | 73 (63.5) | 297 (38.3) | |

| Female | 89 (76.7) | 42 (36.5) | 479 (61.7) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 3.0 | 23.9 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 0.373 |

| < 25 | 84 (72.4) | 74 (64.3) | 536 (69.1) | |

| ≥ 25 | 32 (27.6) | 41 (35.7) | 240 (30.9) | |

| Cigarette smoking (n [%]) | 7 (6.1) | 23 (20.2) | 84 (10.9) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol consumption (n [%]) | 45 (39.8) | 74 (64.3) | 339 (43.9) | < 0.001 |

| Nocturnal GERD (n [%]) | 32 (27.6) | 22 (19.1) | 32 (4.1) | < 0.001 |

NERD, nonerosive reflux disease; ERD, erosive reflux disease; BMI, body mass index GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Chi-square test and ANOVA.

A history of smoking was more common in the ERD group (20.2%) than the NERD group (6.1%, P = 0.002) (Table 2). Similarly a history of alcohol consumption was more common in the ERD group (64.3%) than NERD group (39.8%, P < 0.001).

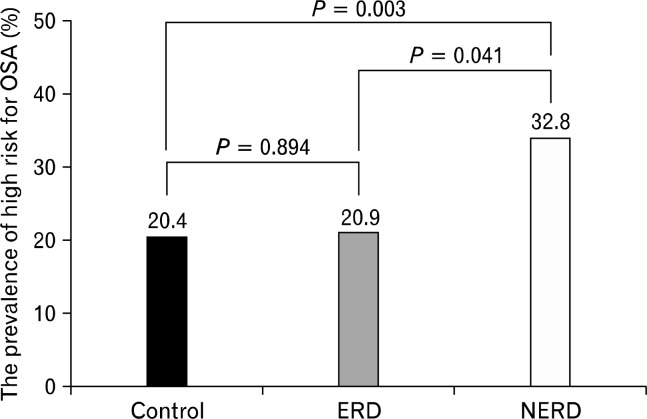

Prevalence of High Risk for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

We found 220 patients at high risk for OSA (21.8%). The proportion of subjects with high risk for OSA was significantly higher in the GERD group (28.2%) than in the control group (20.4%, P = 0.036). Among the 3 groups, a significantly higher number of patients in the NERD group (32.8%) had high risk for OSA than the ERD group (20.9%) and controls (20.4%, P = 0.010) (Fig. 2). The number of subjects at high risk for OSA was not significantly different between the ERD group and controls. (P = 0.894). Typical GERD symptoms of more than once a week were found in 24.3% (28/115) of patients with ERD, but the presence (21.4%) or absence of (20.7%) GERD symptoms was not associated with high risk for OSA.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) among non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), erosive reflux disease (ERD) and control groups. In all, 32.8% patients in the NERD group, 20.9% in the ERD group and 20.4% in the control group had high risk for OSA (P = 0.010).

Risk factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

On univariate analysis, high risk of OSA was related to age ≥ 55 years (P < 0.001), a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 (P < 0.001), nocturnal GERD (P = 0.050) and NERD (P < 0.001). However, ERD was not related to high risk of OSA (P = 0.894). Sex, a history of smoking, and alcohol consumption were not related to high risk of OSA. On multivariate analysis, age ≥ 55 years (odds ratio [OR], 1.83; P < 0.001), a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (OR, 2.76; P < 0.001) and NERD (OR, 1.82; P = 0.011) were independent risk factors related to high risk of OSA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Based on Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses

| Number (%) of high risk for OSA | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| < 55 | 80/496 (16.1) | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 55 | 140/511 (27.4) | 1.96 (1.44–2.66) | < 0.001 | 1.83 (1.33–2.51) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 93/397 (23.4) | 1 | ||||

| Female | 127/610 (20.8) | 0.86 (0.63–1.16) | 0.322 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| < 25 | 111/691 (16.1) | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 109/316 (34.5) | 2.82 (2.07–3.85) | < 0.001 | 2.76 (2.01–3.78) | < 0.001 | |

| Cigarette smokinga | ||||||

| No | 197/889 (22.2) | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 21/114 (18.4) | 0.79 (0.48–1.31) | 0.363 | |||

| Alcohol consumptiona | ||||||

| No | 115/543 (21.2) | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 103/458 (22.5) | 1.08 (0.80–1.46) | 0.617 | |||

| Nocturnal GERD Sx | ||||||

| No | 194/921 (21.1) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 26/86 (30.2) | 1.63 (1.00–2.65) | 0.050 | 1.55 (0.90–2.66) | 0.112 | |

| Group | ||||||

| Control | 158/776 (20.4) | 1 | 1 | |||

| ERD | 24/115 (20.9) | 1.03 (0.64–1.68) | 0.894 | 0.93 (0.56–1.55) | 0.789 | |

| NERD | 38/116 (32.8) | 1.91 (1.25–2.92) | < 0.001 | 1.82 (1.15–2.90) | 0.011 | |

Missing values: cigarrette smoking (n = 4) and alcohol consumption (n = 6).

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; BMI, body mass index; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; Sx, symptom; ERD, erosive reflux disease; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease.

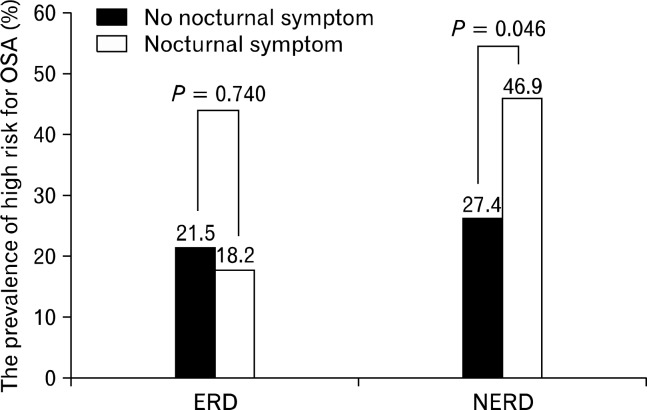

Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Of the 231 subjects with GERD, nocturnal GERD was observed in 54 (23.4%). Nocturnal GERD was more frequent in the NERD group (27.6%) than in the ERD group (19.1%, P < 0.001). In the 116 subjects with NERD, high risk of OSA occurred more frequently in patients with nocturnal GERD (46.9%) than in those who did not (27.4%, P = 0.046). However, for the 115 patients with ERD, there was no significant difference in the rates of high risk for OSA according to nocturnal GERD (18.2% vs. 21.5%, P = 0.740) (Fig. 3). While age ≥ 55 years was an independent risk factor for high risk of OSA in the ERD group (OR, 6.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.03–20.83; P = 0.002), nocturnal GERD was the only independent risk factor in the NERD group (OR 2.97; 95% CI, 1.19–7.84; P = 0.019).

Figure 3.

Comparison of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) risk between patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and those with erosive reflux disease (ERD) based on nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In the NERD group, high risk for OSA occurred more frequently in patients with nocturnal GERD. However, in the ERD group, there was no significant difference in the rate of high risk for OSA.

Discussion

This study shows that GERD can be associated with OSA in the general population. Recent studies have suggested that symptomatic GERD and OSA are closely related. However, the exact causative relationship remains unclear. GERD occurs in up to 60% of OSA patients; comparatively, it occurs in only 20% of the general population.14–16 In addition, several studies showed that OSA was more common in GERD patients than in the general population.3,17,18 A recent study showed that the prevalence of OSA was higher over 10% in GERD patients compared with general population.3 However, other studies did not use a questionnaire and endoscopy to evaluate GERD. Furthermore, some of the patients with other gastrointestinal disease such as gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, or gastric cancer may have been included in the GERD group. In our study, we performed endoscopy in all study participants and excluded patients who were diagnosed with other gastrointestinal disorders.

In this study, we found that an increased risk for OSA was more frequent in patients with NERD than in those with ERD and controls. No difference in high risk for OSA was found between ERD patients and controls. In contrast with the findings of our study, another study in Egyptian patients found that pulmonary manifestations were significantly higher in ERD patients than in NERD patients.19

Although we report an association between high risk of OSA and NERD, we did not identify any obvious explanation for the mechanism of this association. We hypothesize that NERD patients may be at risk of extraesophageal symptoms. Most studies have shown that NERD patients have other digestive symptoms, such as functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome, as well as non-digestive symptoms, such as chest pain, urinary symptoms, and mood disorder with a higher frequency than that observed in ERD patients.20–22 An observational study demonstrated that non-digestive symptoms, including chest pain, dyspnea, cough, urinary symptoms, and sleep disturbance, were more frequent in pH-positive NERD patients compared to that in ERD patients.22 In addition, sleep dysfunction and anxiety were higher in NERD patients compared with controls.23

There is insufficient evidence for a causal relationship between GERD and OSA. One explanation for this is that both disorders have common risk factors, such as obesity and alcohol consumption, and the association between the two disorders is complex. Treatments used for GERD or OSA often improve the symptoms of the other. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure treatment for OSA improves the symptoms of GERD.24,25 Proton pump inhibitor treatment reduces the obstructive events and improves the apnea hypopnea index in OSA patients.26,27 In patients with OSA, intrathoracic pressure is increased negatively during an apnea. In addition, hyperventilation after sleep apnea is related to the mechanism of GERD. The connection between the diaphragm and lower esophageal sphincter through the phrenoesophageal ligament is considered the mechanism of GERD in OSA patients.2 Conversely, nocturnal acid regurgitation, repetitive microaspiration of gastric acid and vagal reflex may induce OSA in GERD patients. Many patients with GERD have nocturnal re-flux symptoms, because sleep itself leads to proximal migration of gastric acid and aspiration into the tracheal-bronchial tree.28 The proximal migration of refluxed gastric contents and microaspiration of acid during sleep can cause inflammation and edema of the upper airway, as well as bronchoconstriction, thereby predisposing to OSA. The refluxed gastric acid in the distal esophagus in GERD also triggers a vagal reflex that can facilitate bronchospasm.29 However, these hypotheses of the OSA pathogenesis in GERD need to be investigated.

Nocturnal GERD is considered to have a greater risk for respiratory complications including OSA.3,30 According to previous studies, nocturnal symptoms of GERD are more common in patients with OSA and may be improved by treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure.25 A recent study also showed that having persistent nocturnal symptoms of GERD is linked to recent development of OSA symptoms.30 In our study, subjects with nocturnal GERD in the NERD group were more frequently at high risk for OSA than those in the ERD group. The ERD group in our study included some subjects without typical reflux symptoms, while the NERD group did not. We did not investigate sleep disturbance in our subjects. Sleep disturbance is known to occur more frequently in NERD than in ERD.31–33 These factors may influence the relationship between nocturnal symptoms of GERD and high risk for OSA in the NERD group.

We acknowledge there are limitations in this study. First, the definition of high risk for OSA was not based on objective measurement such as a polysomnography but on a subjective, self-reported questionnaire. We were unable to perform a polysomnography in many of the study participants. Although polysomnography is the standard diagnostic tool used to evaluate OSA, the BQ has been frequently used as the screening test for OSA in large-scale studies.5 The sensitivity and specificity of the BQ results varied, perhaps because of the different cutoff values for OSA diagnosis. A recent validation study reported that the sensitivity was 86%, and specificity was 95% when a high-risk OSA category was defined by the BQ predicted an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5.10 A validation study for Korean version of the BQ showed excellent internal consistency and reliability. High-risk groups for OSA defined by the Korean BQ predicted an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5 with a sensitivity of 69% and a specificity of 83%.12 Second, we diagnosed and classified GERD groups using the questionnaire for GERD symptoms and endoscopic findings without esophageal pH monitoring. This might have led to NERD being over-diagnosed because functional dyspepsia, esophageal motility disorder, and other gastrointestinal disorders were included in the NERD group. However, we attempted to distinguish GERD more accurately by defining reflux symptoms only when they occurred at least once a week or more. We also performed gastroduodenal endoscopy in all subjects to exclude other gastrointestinal diseases. Third, patients with severe GERD (LA classification C or D) accounted for only a minority of patients in our study because we included many subjects from the health promotion center.

In conclusion, high risk for OSA developed more frequently in GERD patients compared with healthy controls. NERD, age ≥ 55 years, and a high BMI might be related to high risk for OSA. The unclear mechanism of the association between OSA and GERD calls out for further studies by using more accurate diagnostic tools (e.g., esophageal pH monitoring for GERD and polysomnography for OSA).

Acknowledgments

The statistical consultation was supported by Catholic Research Coordinating Center of the Korea health 21 R & D Project (A070001), Ministry of Health & Welfare Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

References

- 1.Jung HK. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:14–27. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demeter P, Pap A. The relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obstructive sleep apnea. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:815–820. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emilsson OI, Janson C, Benediktsdóttir B, Júlíusson S, Gíslason T. Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux, lung function and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea: Results from an epidemiological survey. Respir Med. 2012;106:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ing AJ, Ngu MC, Breslin AB. Obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2000;108(suppl 4a):120S–125S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmadi N, Chung SA, Gibbs A, Shapiro CM. The Berlin questionnaire for sleep apnea in a sleep clinic population: relationship to polysomnographic measurement of respiratory disturbance. Sleep Breath. 2008;12:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11325-007-0125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho YS, Choi MG, Jeong JJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Asan-si, Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:747–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong JJ, Choi MG, Cho YS, et al. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in the Korean population. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6388–6394. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh JH, Kim TS, Choi MG, et al. Relationship between Psychological Factors and Quality of Life in Subtypes of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gut Liver. 2009;3:259–265. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh JH, Choi MG, Park JM, et al. The clinical characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with laryngeal symptoms who are referred to gastroenterology. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:465–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma SK, Vasudev C, Sinha S, Banga A, Pandey RM, Handa KK. Validation of the modified Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang K, Park KS, Kim JE, et al. Usefulness of the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at high risk for obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based door-to-door study. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:803–810. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse CA, Quan SF, Mays MZ, Green C, Stephen G, Fass R. Is there a relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and gastroesophageal reflux disease? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:761–768. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valipour A, Makker HK, Hardy R, Emegbo S, Toma T, Spiro SG. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in subjects with a breathing sleep disorder. Chest. 2002;121:1748–1753. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guda N, Partington S, Vakil N. Symptomatic gastro-oesophageal reflux, arousals and sleep quality in patients undergoing polysomnography for possible obstructive sleep apnoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1153–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gislason T, Janson C, Vermeire P, et al. Respiratory symptoms and nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study of young adults in three European countries. Chest. 2002;121:158–163. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maher MM, Darwish AA. Study of respiratory disorders in endoscopically negative and positive gastroesophageal reflux disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:84–89. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.61233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vries DR, Van Herwaarden MA, Baron A, Smout AJ, Samsom M. Concomitant functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome decrease health-related quality of life in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:951–956. doi: 10.1080/00365520701204204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung HK, Halder S, McNally M, et al. Overlap of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: prevalence and risk factors in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerman J, Hershcovici T. Non-esophageal symptoms cannot differentiate between erosive reflux esophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a referred population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:797–802. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.579997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JY, Kim N, Seo PJ, et al. Association of sleep dysfunction and emotional status with gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:344–354. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerr P, Shoenut JP, Millar T, Buckle P, Kryger MH. Nasal CPAP reduces gastroesophageal reflux in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1992;101:1539–1544. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green BT, Broughton WA, O’Connor JB. Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:41–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zamagni M, Sforza E, Boudewijns A, Petiau C, Krieger J. Respiratory effort. A factor contributing to sleep propensity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1996;109:651–658. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasilewska J, Semeniuk J, Cudowska B, Klukowski M, Debkowska K, Kaczmarski M. Respiratory response to proton pump inhibitor treatment in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Sleep Med. 2012;13:824–830. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orr WC, Heading R, Johnson LF, Kryger M. Review article: sleep and its relationship to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 9):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harding SM. Gastroesophageal reflux, asthma, and mechanisms of interaction. Am J Med. 2001;111(suppl 8A):8S–12S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emilsson ÃsI, Bengtsson A, Franklin K, et al. Nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux, asthma and symptoms of OSA: a longitudinal, general population study. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:1347–1354. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00052512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yi CH, Hu CT, Chen CL. Sleep dysfunction in patients with GERD: erosive versus nonerosive reflux disease. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:168–170. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318141f4a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, Kim N, Seo P, et al. Association of sleep dysfunction and emotional status with gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:344–354. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju G, Yoon IY, Lee SD, Kim N. Relationships between sleep disturbances and gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asian sleep clinic referrals. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]