Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) belongs to a category of adult neurodegenerative conditions which are associated with intracellular and extracellular accumulation of neurotoxic protein aggregates. Understanding how these aggregates are formed, secreted and propagated by neurons has been the subject of intensive research, but so far no preventive or curative therapy for AD is available and clinical trials have been largely unsuccessful. Here we show that deficiency of the lysosomal sialidase NEU1 leads to the spontaneous occurrence of an AD-like amyloidogenic process in mice. This involves two consecutive events linked to NEU1 loss-of-function – accumulation and amyloidogenic processing of an oversialylated amyloid precursor protein in lysosomes, and extracellular release of Aβ-peptides by excessive lysosomal exocytosis. Furthermore, cerebral injection of NEU1 in an established AD mouse model substantially reduces β-amyloid plaques. Our findings identify an additional pathway for the secretion of Aβ and define NEU1 as a potential therapeutic molecule for AD.

Introduction

The amyloidoses comprise a group of diseases characterized by the abnormal deposition of insoluble fibrillar proteins, called amyloid deposits, in different organs including the brain1. These deposits are usually the result of increased synthesis or altered degradation of specific proteins or protein fragments. Amyloid deposition in the brain is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent, age-related neurodegenerative condition worldwide, which is associated with progressive decline of cognitive functions and dementia2. Although the precise mechanisms leading to AD pathology are not yet fully understood, it is well established that the two types of protein aggregates accumulating in AD brains are primarily composed of proteolytic fragments of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles. Aberrant processing of APP by the β–secretase BACE1, (β-site-APP-cleaving enzyme 1), generates an amyloidogenic APP-C-terminal fragment (CTF), which is further cleaved by the presenilin-containing γ-secretase complex into two main amyloid β-peptide isoforms (Aβ): Aβ-40 and Aβ-423,4,5. Aβ-42 is considered the most toxic peptide, which in vitro assembles into fibrils at micromolar concentrations and at acidic pH, and functions in vivo as seeding point for the deposition of amyloid into senile plaques 6,7,8. Although most of the Aβ is found extracellularly, it is now accepted that it may also reside in neurons9,10,11. This intracellular pool may be linked to extracellular Aβ, because an inverse relationship between plaque numbers and Aβ intraneuronal immunoreactivity has been demonstrated 10. These findings suggest that the intracellular accumulation of Aβ represents an early event in AD aetiology, preceding the deposition of the extracellular pool9,11.

It is still unclear, however, how this intracellular Aβ is deposited outside the cells and how it aggregates into plaques. It has been proposed that Aβ, like other toxic proteins, can “spread” from one cell to another via prion-like mechanisms of transmission including passive release/membrane rupture, cell to cell nanotubes and exocytosis12,13. Indeed, it has been shown that intracellular Aβ oligomers can be transferred from neuron to neuron via direct contacts14, and APP, CTF and Aβ have been found in multivesicular bodies and released in association with exosomes15,16,17,18. These recent observationsraise the possibility that intracellular Aβ can be released by these or other, as yet unknown, regulated exocytic processes. The extracellular Aβ may then be recaptured by an endocytic mechanism by neighbouring or distant neurons, thereby propagating the transmission of the toxic peptide. In fact, changes in the morphology and function of the endosomal system have been described as the earliest biochemical alterations seen in AD brains11,19,20,21. In addition, the findings of reduced autophagic clearance22 and accumulation of lysosomal cathepsins in the amyloid plaques23,24,25 directly implicate the lysosomal compartment in the development and progression of AD.

The importance of a fully functional lysosomal system in neural cell homeostasis is well recognized in the large group of neurodegenerative lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs). These primarily pediatric disorders often display signs of premature cellular aging26. Therefore, they may represent ideal models to identify basic mechanisms of CNS pathogenesis and provide insight into more common, adult neurodegenerative conditions. This has been recently highlighted by the discovery of a genetic association between Parkinsonism and Gaucher disease, caused by mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene, GBA127,28. Parkinson’s disease patients have an increased rate of GBA1mutations, defining lysosomal GBA1 as the most common risk factor for the development of this disease. We now provide evidence, in mice, of another link between age-related neurodegeneration and lysosomal dysfunction, by showing that deficiency of the lysosomal sialidase NEU1 (neuraminidase 1) in the LSD sialidosis is at the basis of an amyloidogenic process reminiscent of AD.

In normal conditions, NEU1 initiates the catabolism of sialoglyconjugates by removing their terminal sialic acids29. The enzyme depends on its interaction with the auxiliary protein protective protein/cathepsin A or PPCA for its compartmentalization in lysosomes and catalytic activation30. Aside from its canonical degradative function, NEU1 regulates the physiological process of lysosomal exocytosis by controlling the sialic acid content of the lysosomal-associated membrane protein-1, LAMP131. Lysosomal exocytosis is a calcium-regulated process that entails the recruitment along the cytoskeletal network of a pool of lysosomes destined to dock at the plasma membrane (PM); this step is mediated by LAMP1. Docked lysosomes then fuse their limiting membrane with the PM in response to calcium influx and release their luminal content extracellularly. Lysosomal exocytosis plays a role in the regulated secretion of lysosomal contents in specialized cells32, and in the replenishment and repair of the PM in virtually all cell types31,33. In the absence of NEU1, oversialylated LAMP1 marks an increased number of lysosomes poised to dock at the PM and engage in lysosomal exocytosis. The end result is the exacerbated release of lysosomal contents, which abnormally remodels the extracellular matrix and changes its composition, along with that of the PM.

Here, we investigate the role of NEU1 and lysosomal exocytosis in the amyloidogenic process found in the brain of the Neu1−/− mice, the only model of excessive lysosomal exocytosis. We show that this process begins with the accumulation in endo-lysosomes of an oversialylated APP, a newly identified substrate of NEU1. Endo-lysosomal APP is then proteolytically cleaved to generate Aβ, which is ultimately released extracellularly by excessive lysosomal exocytosis. Remarkably, intracranial injection of NEU1 in the AD model 5XFAD reduces the numbers of amyloid plaques and the levels of amyloid peptides. Thus, NEU1 may represent a risk factor for the development of AD-like amyloidosis and in this respect could be explored as a therapeutic approach for AD.

Results

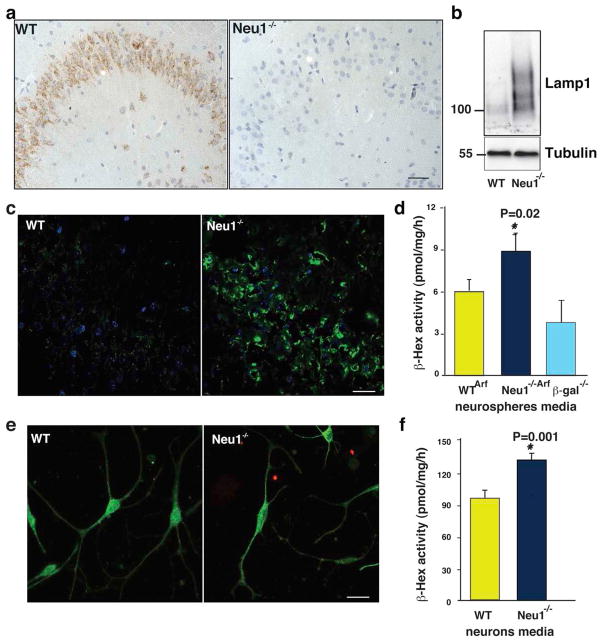

Excessive Lysosomal Exocytosis in Neu1−/− Neural Cells

Neu1−/− mice have profound systemic and neurological abnormalities, are smaller in size than their wild-type littermates and have a shortened lifespan (~5 months). At a late stage of the disease, they appear weak and debilitated, and suffer from dyspnea, edema, gait abnormalities, and tremor34,35. By mapping Neu1 expression in the wild-type mouse brain we found that the enzyme was distributed evenly throughout the parenchyma (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Fig. S2), but was particularly abundant in the hippocampus (Fig. 1a). In the Neu1−/− brain, deficiency of the enzyme was accompanied by increased levels of Lamp1, whose expression is normally low in the wild-type brain (Fig. 1c). In addition, Lamp1 accumulated in an oversialylated state (Fig. 1b). Although Lamp1 has been found up-regulated in other LSDs36,37 due to expansion of the lysosomal compartment, in the context of a Neu1 deficiency upregulation of the protein coupled to its oversialylation results in increased lysosomal exocytosis31,38. Thus, we tested the extent of lysosomal exocytosis in primary neurospheres, by measuring as marker of this process the activity lysosomal β-hexosaminidase (β-hex)33,39 in the culture medium.. These cells were isolated from pups obtained by crossing WT or Neu1−/− mice with Arf−/− mice 40, in order to improve their self-renewaland culturing time41,42. Neurospheres from WT/Arf−/− (WTArf) and Neu1−/−/Arf−/− (Neu1−/−/Arf) had similar cell composition (Supplementary Fig. S3a), but β-hex activity was substantially increased only in the medium of the Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres but not in their cell pellets (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig S3b). Thus, excessive lysosomal exocytosis occurs in the deficient cells. In contrast, β-hex activity measured in the medium of neurospheres isolated from β-galactosidase-deficient mice, a model of the LSD GM1-gangliosidosis43, was in the normal range (Fig. 1d), indicating that exacerbated lysosomal exocytosis is linked to Neu1 deficiency. To determine which cell type in the neurosphere cultures was more exocytic, we assayed for lysosomal exocytosis WT and Neu1−/− primary astrocytes and hippocampal neurons differentiated from neurospheres44 (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. S3c). The activity of β-hex was comparable in the medium of the astrocyte cultures (Supplementary Fig. S3d), while it was increased in the medium of Neu1−/− neurons (Fig. 1f), defining this population of cells as the most exocytic. Thus, Neu1-deficiency in neurons enhances their lysosomal exocytosis potential.

Figure 1. Altered expression of Lamp1 in the brain of Neu1−/− mice.

a, Neu1 expression is high in the CA3 region of the WT hippocampus. b, Oversialylation of Lamp1 shown on immunoblots of WT and Neu1−/− hippocampal lysates probed with the indicated antibody. c, Loss of Neu1 is accompanied by accumulation of Lamp1. d, Extent of lysosomal exocytosis measured as β-hex enzyme activity in the culture medium of neurospheres. Neu1−/−/Arf hippocampal neurospheres have enhanced lysosomal exocytosis. e, Representative picture of WTArf and Neu1−/−/Arf hippocampal neurons stained with β-III tubulin (green) and GFAP (red). f, Neu1−/−/Arf hippocampal neurons have enhanced lysosomal exocytosis as assessed by β-hex enzyme activity measured in the culture medium. Asterisks indicate statistically significant results, as determined by the Student’s t test. Data are represented as mean ± SD (error bars); n=3. Mice used for histological analyses were 5 months of age. Scale bars 20μm.

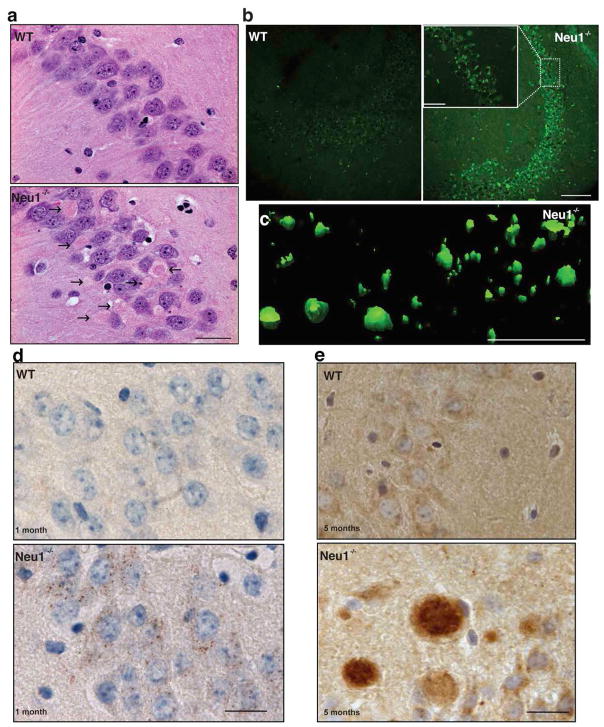

Neu1 Deficiency Leads to AD-Like Pathology

Increased exocytosis of lysosomal contents from neurons could impact on the architecture and composition of the brain parenchyma. In fact, histopathological examination of the Neu1−/− brain identified numerous abnormal eosinophilic bodies, primarily clustered in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 2a) and the fimbria. These bodies were heterogeneous in size and shape, and mostly contained amorphous, granular, proteinaceus material that resembled amyloid. They were visualized throughout the CA3 region and, to some extent, in the cortex, after systemic, in vivo injection of Neu1−/− mice with the Congo red/Chrysamine-G fluorescent derivative Methoxy-X04, which has been shown to bind with high affinity to amyloid fibrils45 (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, ultrastructural examination of the Neu1−/− hippocampal region identified numerous swollen dystrophic neurites (Supplementary Fig. S4), a feature also associated with amyloid plaques. Combined these pathological changes downstream of Neu1 deficiency were reminiscent of those seen in several neurological amyloidoses, including early stage AD46.

Figure 2. Pathologic abnormalities in the Neu1−/− hippocampus.

a, H&E staining demonstrated numerous eosinophilic bodies (arrows) in the CA3 region of the Neu1−/− brain (Mice 5 months of age). Scale bar 20μm b, Methoxy-XO-4–stained amyloid deposits in Neu1−/− hippocampus Scale bars 100μm (Mice 5 months of age) (scale bar for zoom in 50μm). c, Z-stacks obtained from confocal images of Neu1−/− Methoxy-XO4+ amyloid deposits were used to build a three-dimensional surface rendering. Scale bar 250μm d, In the Neu1−/− hippocampus, APP starts to accumulate intracellularly as early as 1 month of age, as revealed by immunohistochemistry analysis with anti-APP N-terminal antibody (brown) e, Amyloid deposits in 5 months old Neu1−/− brain stained positive for APP (N-terminal antibody). d and e scale bars 20μm.

We therefore asked whether the amyloid bodies spontaneously arising in Neu1−/− brains shared features with Alzheimer β-amyloid. To address this point, we performed a series of immunostainings of brain sections, using antibodies against full length APP (N-terminal antibody). We found that APP accumulated in the Neu1−/− CA3 hippocampal neurons as early as one month of age, and was resolved in discrete intracellular puncta (Fig. 2d). As the animals aged APP+ bodies increasingly formed (Fig. 2e), and were most prominent towards the end of their lifespan. At this time point, the majority of these bodies were also immunoreactive for ubiquitin and neurofilaments, indicating that Neu1−/− hippocampal neurons underwent extensive cytoskeletal remodelling and showed impaired intracellular trafficking (Supplementary Fig. S5a, b). Accumulation of APP was also assessed by quantitative analysis of band intensity on immunoblots of Neu1−/− hippocampal lysates (Fig. 3a, b). The presence of amyloid deposits and accumulated APP in the Neu1−/− mice support the idea that NEU1 deficiency may predispose to an AD-like phenotype.

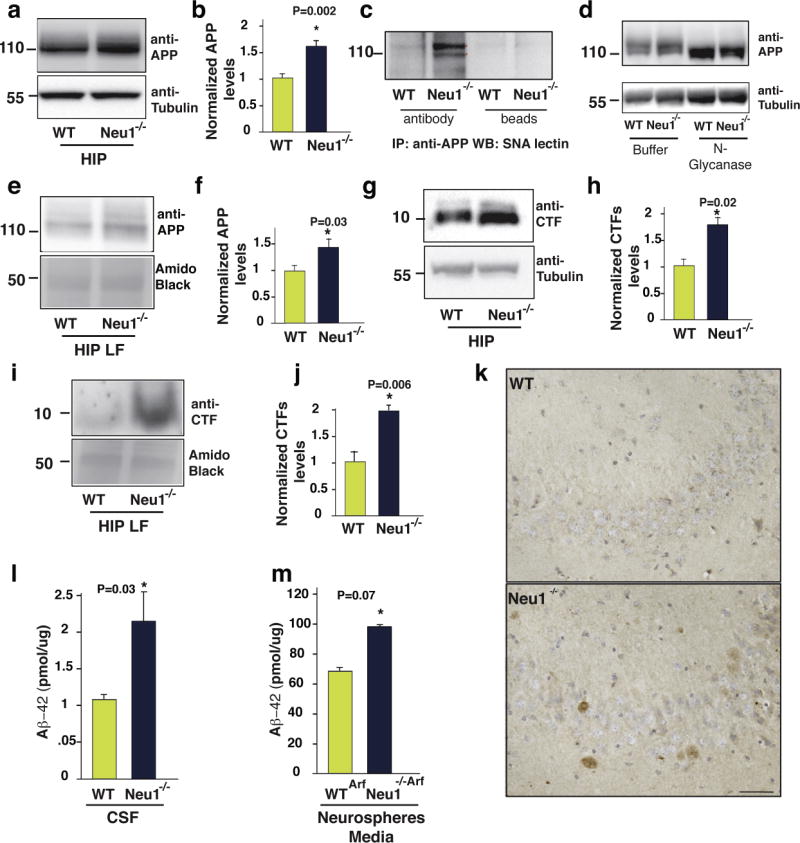

Figure 3. APP is a natural substrate of Neu1 and is abnormally processed in Neu1−/− lysosomes.

a and b, APP levels are increased in Neu1−/− total hippocampal lysates (HIP) as demonstrated by immunoblots (a) and by densitometric analysis (b). c, APP was immunoprecipitated from WT and Neu1−/− HIP and probed on blots with Sanbucus nigra lectin (SNA). d, Equal amounts of HIP lysates were treated with N-glycanase, sialidase, and O-glycanase and probed on blots with anti-APP N-terminal antibody. e, Immunoblots of WT and Neu1−/− HIP-enriched-LF shows APP accumulation in the Neu1−/− samples. f quantification of (e). g and i, β-CTF levels are increased in Neu1−/− HIP lysates and Neu1−/− hippocampal-enriched-LF, respectively. h and j, quantification of (g) and (i). k, Representative Aβ-peptide staining in WT and Neu1−/− brain sections shows immunoreactivity only in Neu1−/−specimens (mouse specific pan Aβ-antibody used on 5 months old brain sections). Scale bar 20μm. l and m, Levels of mouse Aβ42 assayed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and in the culture medium of neurospheres respectively.

Normalized APP and CTFs refer to the ratio of WT vs Neu1−/− bands. These were calculated by densitometric analysis of single bands on immunoblots probed with anti APP or β-CTF antibodies and amido black bands and anti-tubulin in WT and Neu1−/− samples. Red asterisks in (c) denote oversialylated bands.

Asterisks on graphic bars indicate statistically significant results, as determined by the Student’s t test. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (error bars); n=3.

APP is a natural substrate of NEU1

Given that APP is a glycosylated and sialylated integral membrane protein that was shown to localize in purified lysosomes47, and that changes in its glycan composition can cause spurious proteolytic cleavage of the protein, leading to increased formation of Aβ48, we thought of testing whether APP could be processed by Neu1 in lysosomes. For this purpose, we first analysed the sialylation status of APP by probing immunoblots of Neu1−/− hippocampal lysates with Sambucus nigra lectin, which binds with high affinity to α-2,6–linked sialic acids. The results showed that in absence of Neu1 APP had increased levels of sialic acids, compared to the WT protein (Fig. 3c). In vitro enzymatic removal of all N-glycans released a core APP protein that was identical in size in the Neu1−/− and WT samples, indicating that the changes in APP levels in the Neu1−/− brain were due to the impaired removal of its sialic acids (Fig. 3d). We next purified lysosomes from Neu1−/− and WT hippocampi through a density gradient. Those fractions with the highest lysosomal acid phosphatase activity (Supplementary Fig. S6) were used for biochemical analyses; indeed, APP was increased in pure lysosomal fractions (LFs) from Neu1−/− hippocampi (Fig. 3e, f). Hence, APP is a bona fide substrate of NEU1 and remains oversialylated in the absence of this enzyme activity. The lack of processing of APP’s glycan chains may lengthen its half-life and explain its accumulation in lysosomes.

A determining step in the amyloidogenic processing of APP is the generation of C-terminal fragments (CTF), which are subsequently cleaved into Aβ3. We thought to ascertain the extent of CTF generated in the Neu1−/− hippocampus as predictive measure of abnormal Aβ processing. CTF levels were substantially elevated in both total hippocampal lysates and LFs isolated from the Neu1−/− brains (Fig. 3g–j), compared to those in WT samples. The increased CTF in Neu1−/− LFs were proteolytically cleaved into Aβ, because we were able to detect endogenous Aβ-peptides in Neu1−/− brain sections, probed with a rodent-specific pan anti-Aβ antibody, but not in WT sections (Fig. 3k). These results prompted us to test for the presence of Aβ42 in the cerebrospinal fluid isolated from WT and Neu1−/− mice, as well as in the culture media of Neu1Arf and Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres. In both sets of Neu1−/− samples we measured substantially increased levels of this peptide (Fig. 3l, m). These results suggest that accumulated APP and CTF are processed into Aβ42 in the lysosomal compartment.

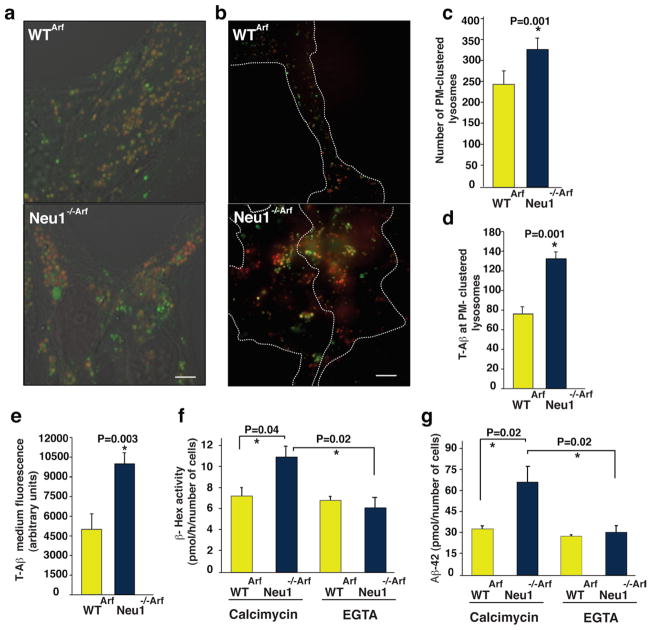

Excessive Lysosomal Exocytosis Promotes Aβ Peptide Release

Given that loss of Neu1 is associated with increased lysosomal exocytosis, we argued that this process could then mediate the extracellular release of lysosomally-generated Aβ42 from lysosomes. To test this, we cultured WTArf and Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres in the presence of a human, TAMRA–conjugated, fluorescent Aβ42 (T-Aβ)8. T-Aβ was similarly taken up by both WT and Neu1−/− cell populations and routed to late endosomes/lysosomes (Fig. 4a). This fraction of the internalized peptide was then trafficked from the endosomes/lysosomes to the PM, as determined by live imaging of lysotracker-labeled lysosomes with total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) (Fig. 4b). This technique allows the visualization of fluorescently labeled organelles in the evanescent field near the cell surface31. Quantification of the number of lysotracker+ organelles proximal to the PM (Fig. 4c) showed that Neu1−/−/Arf cells had substantially more T-Aβ–containing-lysosomes clustered at the PM than did WTArf cells (Fig. 4d). Moreover, when neurospheres were maintained in T-Aβ–free medium for 24 h after exposure to the peptide, we could recover more T-Aβ fluorescence exocytosed from the Neu1−/−/Arf cells than from the WTArf cells (Fig. 4e). To further confirm that the Aβ-peptide was released from Neu1−/− cells by lysosomal exocytosis, we tested whether induction/inhibition of this process would affect the amount of Aβ peptide released in the medium. WTArf and Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres were cultured in the presence of T-Aβ for 24 h; cells were then treated with the calcium ionophore calcimycin, which enhanceslysosomal exocytosis by promoting the calcium-dependent fusion of lysosomes docked at the PM39. We found that the medium from calcimycin-treated Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres had higher levels of β-Hexactivity than that from treated WT cells (Fig. 4f). This was paralleled by substantially increased levels of Aβ-42 peptide in the calcimycin-treated Neu1−/− samples (Fig. 4g). Most importantly, Neu1−/− cells maintained in calcium-free medium (+EGTA) prior to the assays to inhibit lysosomal exocytosis had normal levels of both β-Hex and Aβ peptide measured in their culture medium (Fig. 4f, g). Thus, in absence of Neu1, Aβ is abnormally exocytosed by lysosomes, a finding that identifies lysosomal exocytosis as an additional mechanism for the extracellular release of this peptide.

Figure 4. Neu1 deficiency and consequent exacerbated Lysosomal Exocytosis promotes Aβ peptide release.

a, Neurospheres isolated from WTArf and Neu1−/−/Arf brains were maintained in culture in the presence of exogenous T-Aβ42 for 24 h and then imaged with confocal microscopy. T-Aβ42 fluorescence (red fluorescence of TAMRA-Aβ42) colocalized with lysotracker (green), marker of endosomes/lysosomes. b, TIRF analysis shows that Neu1−/−/Arf hippocampal neurospheres have enhanced T-Aβ levels in PM-docked lysosomes (lysostracker green). c, Quantification of PM-docked lysosomes shows an increased number of clustered organelles at the PM of Neu1−/−/Arf cells. d, Quantification of T-Aβ levels present in PM-docked lysosomes shows higher amounts of T-Aβin Neu1−/−/Arf cells than in WT samples. e, TAMRA fluorescence was assayed in neurospheres’ culture medium as indicator of the levels of T-Aβ released by lysosomal exocytosis. f, g, Extent of lysosomal exocytosis measured as β-hex enzyme activity and human Aβ-42 assayed in the culture medium of WTArf and Neu1−/−/Arf neurospheres treated with the calcium ionophore calcimycin in presence or absence of EGTA which effectively blocks the lysosomal exocytosis.

Asterisks on graphic bars indicate statistically significant results, as determined by the Student’s t test. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (error bars); n=3. a and b scale bars 20μm

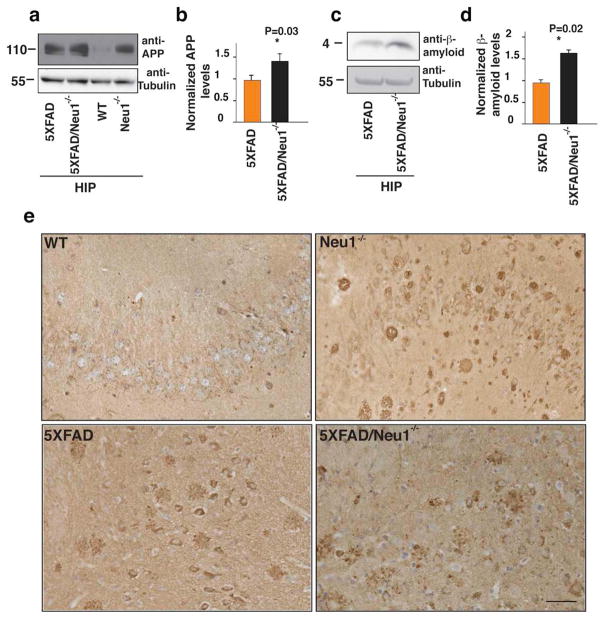

NEU1 Ablation Affects Plaque Formation in 5XFAD Mice

Our results so far point to a Neu1-dependent AD-like amyloidogenic process arising spontaneously in the Neu1−/− mice. To further ascertain whether Neu1 deficiency could exacerbate an existing amyloidogenic process, we crossed the Neu1−/− mice with a well-characterized model of early onset familial AD, the 5XFAD mice49. These mice overexpress human APP and presenilin-1, both harboring mutations found in AD patients. Expression of the transgenes is under the control of the neural-specific elements of the mouse Thy1 promoter. In 5XFAD mice intraneuronal Aβ-42 accumulation starts at six weeks of age just prior to amyloid deposition, which begins in the subiculum of the hippocampus at two months and propagates throughout the brain in older mice49.

We first assessed the effects of Neu1 ablation in the double mutant mice (5XFAD/Neu1−/−) by recording their ambulatory activity in an open space. Both the double mutants and the Neu1−/− mice showed similar walking pattern abnormalities and limited exploratory capacity (Supplementary Movie 1–4). We next demonstrated that APP was present in higher amounts in hippocampal lysates from 5XFAD/Neu1−/− double mutants than in those from 5XFAD mice (Fig. 5a, b). Remarkably, APP levels in Neu1−/−lysates were comparable to those in 5XFAD (Fig. 5a). Accumulation of APP was paralleled by increased levels of β-amyloid in 5XFAD/Neu1−/− animals (Fig. 5c, d). Histological analyses of brain sections revealed higher levels of APP in the 5XFAD/Neu1−/− subiculum when compared to the levels in the same region of the 5XFAD (Fig. 5e). Hence, deficiency or downregulation of NEU1 may represent a risk factor for the development of AD.

Figure 5. NEU1 loss of function in a model of AD accelerates β-amyloid production.

a, c, APP and β-amyloid levels respectively were analyzed in hippocampal lysates from 5XFAD, 5XFAD/Neu1−/−and Neu1−/− hippocampi. b, d, quantification of (a) and (c); The normalized levels of APP and β-amyloid were calculated by densitometric analysis of single bands on immunoblots probed with anti APP or β-amyloid antibodies and anti-tubulin in 5XFAD and in 5XFAD-Neu1−/− samples. Anti-tubulin antibody was used as loading controls; Asterisks on graphic bars indicate statistically significant results, as determined by the Student’s t test. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (error bars); n=3 e, Representative pictures of full length APP staining in WT, 5XFAD, 5XFAD/Neu1−/− and Neu1−/−hippocampal regions (5XFAD, 5XFAD/Neu1−/− mice were 3 months of age, WT and Neu1−/− mice were 5 months of age) (N-terminal antibody against APP). Scale bar 20μm.

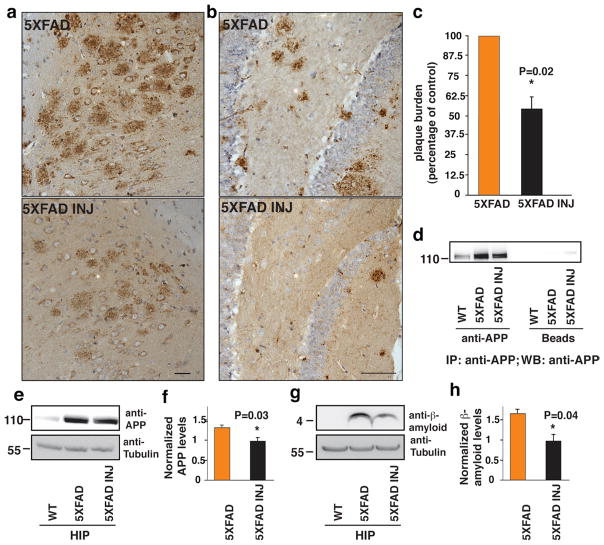

NEU1 Upregulation Reverses AD Pathology in 5XFAD Mice

We next tested whether augmentingNeu1 activity in the 5XFAD model would revert or delay the amyloidogenic process. To generate high levels of Neu1 activity in the brain we used an admixture of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) expressing human NEU1 and its auxiliary chaperone PPCA30,50. This vector combination produced the highest NEU1 activity when transduced into Neuro2a neuroblastoma cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S7a). The AAV-PPCA/AAV-NEU1 mixture was stereotactically injected unilaterally into the hippocampal region of 4–6-month-old 5XFAD mice. Four weeks after injection, immunohistochemical analyses of brain sections revealed a remarkable overall reduction of plaque burden in the hippocampal region of the AAV-injected mice mice compared to that of 5XFAD mice injected only with carrier solution (Fig. 6a, b). This was accompanied by high levels of expression of NEU1 and PPCA in the same region of the AAV-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S7b, c). We also quantified the number of amyloid plaques in serial sections of the subiculum from 4 AAV-injected animals and found that the surface occupied by the plaques was reduced by 44.3% ± 6.2% in these mice, compared to the same area in the carrier solution-injected mice (Fig. 6c). Finally, boosting the activity of NEU1 in the hippocampal area of the AAV-injected 5XFAD had a direct effect on the levels of APP (Fig. 6d–f) and β-amyloid (Fig. 6g, h), which were substantially reduced. Collectively, these results put forward the idea that NEU1 could be an effective therapeutic agent for AD.

Figure 6. NEU1 upregulation in 5XFAD reduces β-amyloid and plaques development.

a, b, Injection of an adeno-associated virus containing human NEU1 and PPCA in the hippocampus of 4 and 6 month-old 5XFAD animals, respectively, (5XFAD INJ) reduced the number of amyloid plaques compared to that seen in 5XFAD animals injected only with carrier solution. Plaques were identified by 4G8 immunostaining (brown). a Scale bar 20μm. b Scale bars 10μm. c, Reduction of amyloid plaques in 5XFAD INJ, as determined by quantification of 4G8 immunostaining (mean ± SD; n=4). d and e, NEU1 overexpression in the 5XFAD INJ mice reduces APP as demonstrated by immunoprecipitation (d) and immunoblotting (e) analyses. f, quantification of (e). g, Reduction of β-amyloid levels in hippocampal lysates from 5XFAD INJ mice. h quantification of (g). The 5XFAD/5XFAD-INJ ratio was calculated by densitometric analysis of single bands on immunoblots probed with anti- APP or β-amyloid antibodies and anti-tubulin in 5XFAD and in 5XFAD INJ hippocampal lysates. Asterisks on graphic bars indicate statistically significant results, as determined by the Student’s t test. Data are represented as the mean ± SD (error bars); n>3

Discussion

The trafficking and deposition of progressively accumulating toxic proteins by diseased neurons is a crucial but poorly understood issue in the field of neurodegenerative diseases. Autophagy and lysosomal mechanisms of degradation have been rapidly emerging areas of interest in this regard51,52. The notion that neurons could release abnormal proteins by lysosomal exocytosis has been postulated but, until now, there was no evidence for such a process. Moreover, the concept that β-amyloid deposited extracellularly in the AD brain could originate from intraneuronal production in the endosomal-lysosomal compartment23,47 has hinted on exocytic processes as likely additional mechanisms for the release of Aβ. Most importantly, the oligomerization/aggregation of Aβ is favored by an acidic environment6, which further indicates that initial oligomerization within the acidic endosomes/lysosomes coupled to a regulated lysosomal release mechanism could be critical in the Aβ toxic life cycle.

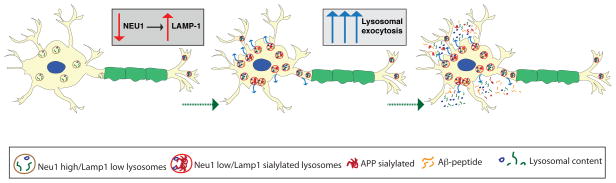

In this study we identify a central role for NEU1 in regulating both the fate of APP by cleaving its sialic acids, and the extracellular release of Aβ by lysosomal exocytosis (Fig. 7). Our data on APP sialic acid content agree with earlier studies that found a positive correlation between increased APP sialylation by overexpression of the α-2,6-sialyltransferase ST6Gal-I and the extracellular release of its metabolites, promoting the secretion of amyloid-β peptides48. This implies that either the biosynthetic or the catabolic control of the sialic acids on APP affects its β-amyloidogenic processing. We propose that in the absence of NEU1, the oversialylation of APP may change its half-life and lead to accumulation of it and/or its metabolites in the endosomal-lysosomal compartment. This accumulated APP would then be more prone to β-amyloidogenic cleavage, resulting in accelerated production of neurotoxic APP end products by the neuronal β-secretase. In this regard, it is noteworthy that BACE1 was shown to reside in the lumen of an acidic intracellular compartment and to function at acidic pH53. Altogether, our findings favor a lysosomal control over the levels of APP and its proteolytic cleavage, which we believe are directly relevant to the pathogenesis of AD.

Figure 7. Schematic Model.

In absence of Neu1, oversialylated APP is abnormally processed in lysosomes and the generated Aβ–peptide is released in the extracellular space via excessive lysosomal exocytosis.

It has been postulated that proteolytically-generated Aβ-peptides may engage in a prion-like mechanism of spreading and be transmitted from cell to cell54 or deposited extracellularly by processes that involve microvesicles or cellular nanotubes13. We now provide evidence that excessive lysosomal exocytosis downstream of Neu1 deficiency mediates the release of Aβ, a finding that identifies this process as a plausible mode of spreading of the toxic peptide (Fig. 7). Moreover, excessive release of endo-lysosomal contents may create in the immediate vicinity of the PM of cells and the extracellular space, an ideal acidic microenvironment that would favor the continuous processing, aggregation and fibrillation of Aβ, ultimately resulting in plaque formation7,8,55. This kind of pathogenic cascade is also in agreement with a large body of work that has involved the endocytic pathway as a major contributor to AD 25,56,57. Increased endocytosis in AD increases the delivery of substrates, including APP and its metabolites, to endo-lysosomes56. The accumulation of incompletely degraded cargoes within NEU1-deficient dysfunctional lysosomes could then contribute to further release of Aβ by lysosomal exocytosis. It is conceivable that excessive lysosomal exocytosis may be counterbalanced by further increased endocytosis in order to maintain PM integrity. In this scenario, endo-lysosomes would be engaged in a self-propagating pathogenic loop, which eventually promotes the generation of Aβ in the endo-lysosomal compartment and its subsequent exocytosis.

Another feature that can be indicative of deregulated lysosomal exocytosis is the increased expression of the NEU1 substrate LAMP1. This protein is present in an oversialylated state in neurons of the Neu1−/− model. Consistent with this finding, LAMP1 has been found upregulated both in AD patients and animal models of the disease, and shown to increase in amounts with disease progression 23,58,59, reiterating the notion that lysosomes are actively engaged in AD pathogenesis. Furthermore, if NEU1 downregulation will be proven in AD brain specimens, the relative levels of NEU1 and LAMP1 may be suggestive of excessive lysosomal exocytosis.

Only 1–5% of AD cases are familial (FAD), i.e. linked to known genetic mutations, and usually develop an early onset form of the disease. The vast majority of the patients contracts the so-called sporadic AD of still unknown aetiology and mostly associated with aging60. Given the complexity of this disease it is foreseeable that it may result from the interplay between deterministic or risk genes, and epigenetic and environmental factors. So far, the strongest genetic risk factor found in sporadic AD patients is Apolipoprotein E, genotype ε4, which is thought to increase the rate of aggregation and decrease the clearance of Aβ61, albeit by still not fully understood mechanisms. We now propose NEU1 as a potential, novel risk factor in hastening the progression of AD. We show that Neu1 deficiency have an additive effect when combined with familial AD mutations in the 5XFAD transgenic model in accelerating β-amyloid formation. We are tempted to speculate that genetic or epigenetic downregulation of NEU1 may exacerbate the development and progression of AD in some of the sporadic cases, although further studies are required to validate this hypothesis.

The need for developing effective treatments for AD is becoming urgent given the projected number of people worldwide who will present with the disease within the next 4 decades3,60. Despite tremendous scientific effort, at the moment the available drugs used in AD patients have had only modest and transient effects, which exclude their curative potential. Recently, new therapeutic strategies have proven effective in clearing extracellular β-amyloid deposition in AD mouse models62, but it is still uncertain whether these approaches may be effective in addressing the intracellular pathobiology, including lysosomal clearance deficits and Intraneuronal Aβ toxicity, that may be critical for neurodegeneration. As demonstrated in this study, AAV-mediated gene therapy could be a suitable therapeutic strategy for AD because it has been successfully applied in clinical trials and preclinical studies50,63. Based on our findings that increasing Neu1 activity in the brain of the 5XFAD mice reduces their β-amyloid plaque burden, we propose that upregulation of NEU1 could be exploited as a novel therapeutic strategy to halt or revert disease pathogenesis.

Methods

Animal models

All procedures in mice were performed according to animal protocols approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and NIH guidelines. Neu1−/− and WT mice were bred into the FVB/NJ and C57BL/6 genetic backgrounds. 5XFAD transgenic mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory.

Enzymatic activities

NEU1 and β-HEX catalytic activities were measured against synthetic substrates 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid, sodium salt and 4MU-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide as reported previously31. Briefly cells were harvested and lysed in water for both assays. To measure NEU1 enzymatic activity 5μl of homogenate was incubated with 5μl of 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid, sodium salt in triplicate in 96 well plates for 1h at 37 °C. To assay β-HEX activity 10μl of homogenate was incubated with 10μl of 4MU-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide. To stop enzyme reactions 200-μl of 0.5 M Carbonate Buffer pH 10.7 was added to all wells. The fluorescence was measured on a plate reader (EX-355, EM-460). The net fluorescence values were compared with those of the linear 4-MU standard curve and were used to calculate the specific enzyme activities. Activities were calculated as nmoles of substrate converted per hour per mg of protein (nmol/hr/mg). Acid phosphatase activity was assayed with the help of the acid phosphatase assay kit from Sigma, according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Media from different cells was collected and centrifuged at 11,000 g for 5 min. Spun down medium was then applied onto a G50 Sephadex column packed in an acidic buffer before performing enzymatic assays.

Elisa of Aβ1–42

The amount of mouse Aβ1–42 and human Aβ1–42 in the cell culture media and in the CSF was determined by using mouse and human Aβ42 ELISA kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse Aβ and human Aβ levels were normalized to respectively total protein levels and total cell number.

Antibodies and Reagents

We used the following commercial antibodies: anti-LAMP1 (Sigma, 1:500), anti-α/β tubulin (Cell Signaling 1:1000), anti-GFAP (DAKO 1:1000), anti-β-III tubulin (TUJ1) (Covance, 1:500)anti-APP (22C11, Millipore 1:500), anti-APP/Aβ (4G8 Covance, 1:500) anti-Aβ (12F4 Covance, 1:500), pan anti-Aβ (Covance, 1:50), anti-ubiquitin (DAKO, 1:1000), anti-neurofilaments (DAKO, 1:1000), Anti Neu1-and anti-cathepsin A (PPCA) antibodies were generated in our laboratory. The anti-C1/6.1 antibody (anti-CTF) was provided by Dr. Nixon. CY3- and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immuno Research, 488- and 594- conjugated secondary antibodies were from Molecular probes. Sanbucus nigra (SNA) lectin was obtained by Vector Labs and used 1:500 dilution. Lysotracker Red DND-99 was obtained from Invitrogen and applied per manufacturer’s instructions. TAMRA-Aβ1–42 was purchased from Anaspec.

Cell Culture

For neurospheres cultures, hippocampi were dissected from brains of P3 to P6 Neu1−/−Arf, WT Arf and βgal−/− mice (mixed sex) and dissociated into a single-cell suspension by 5 min incubation in TrypLE Express (Invitrogen) and trituration with glass pipettes. For immunofluorescence analysis, neurospheres were transferred onto glass coverslips, coated sequentially with poly-L-ornithine (10 μg ml−1) (Sigma) and laminin (5 μg ml−1) (Invitrogen). After an additional 48 hr, attached neurospheres were fixed in PBS containing 4% PFA, washed, and processed for immunocytochemical analysis. Images were analyzed with confocal laser scanning microscope (LEICA, TCS-NTSP). Astrocytes were isolates from P1–3 postnatal animals and dissociated into a single-cell suspension by 5 min incubation in 2.5% trypsin (Invitrogen) and 1% (wt/vol) DNase (Invitrogen) and trituration with glass pipettes. Single-cells were resuspended in growth medium containing MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% FBS (Sigma), 5% Horse serum (Invitrogen). For cell uptake experiments, neurospheres were dissociated an attached on laminin/poly-L ornithine coated slides and incubated with 250nM TAMRA-Aβ1–42. After incubation with TAMRA-Aβ1–42, neurospheres were washed to remove the compound present in the culture medium. After 24h of recovery time, medium was collected in a plate that was excited at 535 nm as a measure of TAMRA-Aβ1–42 exocytosed. Neuro 2a, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line, was kindly provided by Dr. Nixon. This line was used as in vitro model system to test NEU1 activity after Adeno-associated viral particles transduction. These cells were maintained in DMEM media (Invitrogen) supplemented with Glutamax (Sigma), penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone).

Hippocampal neurospheres were differentiated into neurons using a recombinant basic FGF- (rh b FGF) stimulation method which promotes the proliferation of neuronal progenitors prior to differentiation44 following a procedure outlined by STEMCELL Technologies. Briefly 25000 dissociated neurospheres cells were plated onto poly-D-lysine (100 μg/mL Invitrogen) coated slides in DMEF:F12 plus N2 supplement (Invitrogen), containing rh b FGF to a final concentration of 20ng/mL without serum. The next day cells were washed and Neuronal basal medium plus SM1 supplement (STEMCELL Technologies) was added. Differentiated cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence with neuronal and glial markers.

Calcimycin Treatment and lysosomal exocytosis inhibition

To induce fusion of docked lysosomes to the PM and extracellular release of their luminal contents, neurospheres were dissociated, counted and plated. They were incubated for 30 min in medium containing 10 μM Calcimycin A23187 (Sigma) in the presence of 1.2 mM CaCl2. In some instances, to inhibit lysosomal exocytosis, cells were washed with Ca2+-free PBS and further maintained in Ca2+-free medium containing 10 mM EGTA, prior to the addition of Calcimycin and CaCl2.

Immunoblotting

Hippocampi were homogenized with a buffer containing: 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1 % SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.05% deoxycholate, and protease inhibitor. Lysosomes were purified from hippocampi of WT and Neu1−/− mice using the Lysosome Isolation Kit (Sigma) following the manufacturer’s protocol with slight modifications. In brief, hippocampi from 4 WT and Neu1−/− mice were homogenized in 4 volumes of 1X extraction buffer in a glass Dounce homogenizer. The nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1.000 × g for 10 min. The postnuclear supernatant was centrifuged at 20.000 × g for 20 min and the resulting pellet, containing the crude lysosomal fraction, was resuspended in a minimal volume of 1X extraction buffer and loaded onto a Optiprep density gradient and centrifuged at 150.000 × g for 4h. 0.5 ml fractions were collected starting from the top of the gradient. Each fraction was assayed for protein concentration and acid phosphatase activity (Sigma). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA-assay (Pierce Biotechnology). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (4–12%, 4–20%, 12% Bis Tris gel, Invitrogen) under reducing conditions and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer and subsequently probed with the specific antibody overnight. Immunoblots were developed by using Enhanced Chemiluminescence Kit (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) or SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). For amyloid detection, prior to the blocking step, membranes were incubated in 0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 45′. For immunoprecipitation analyses, hippocampal extracts (500 μg) were diluted in 250 μl PBS/0.2% BSA with antibodies (2.5 μg; anti-APP; 4G8 or 22C11) overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. Samples were incubated for an additional hour after the addition of BSA (2%) blocked Protein G beads (Invitrogen). The beads were washed 3 times in PBS, and proteins were eluted with sample loading buffer prior to immunoblot (4–12% Bis Tris gel; Invitrogen). Proteins then transferred onto PVDF membranes were probed with an anti–APP antibody or biotynilated SNA lectin. Full gel scans can be found in Supplementary Figures S8–S11.

Methoxy-XO4 in vivo injections

For in vivo imaging studies, WT and Neu1−/− mice (n = 3) were injected intra peritoneally with 10 mg/kg methoxy-X04 45. Mice were anesthetized and perfused with PBS 24 h after the injection. The brains were collected, sliced at 200 μm and imaged. Three-D renderings of Methoxy-XO4-labeled amyloid were created from z-stack acquisitions using Imaris 6.0 software.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Mouse brains were collected after PBS perfusion and fixed with 4% PFA for 12 h at 4°C. Brain tissues were incubated over night in 20% sucrose at 4°C. Finally, tissues were embedded in TFM tissue freezing medium (Triangle biomedical sciences, Inc.) and snapfrozen in liquid nitrogen. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) analyses were performed on 10 μm thick serial cryosections or paraffin sections. For IHC, after blocking (0.1% BSA, 0.5% Tween-20 and 10% normal serum), sections were incubated overnight at room temperature with the specific antibody diluted in blocking buffer. The sections were washed and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA) for 1 hour. Endogenous peroxidase was removed by incubating the sections with 0.1% hydrogen peroxidase for 30 minutes. Antibody detection was performed using the ABC Kit and diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin according to standard method. For IHC with 4G8 or Aβ42 antibodies, tissue sections were pretreated with formic acid (70%) before the blocking step. For IF, after blocking with 0.1% BSA, 0.2% saponin and 10% normal serum, the specific antibody diluted in blocking buffer was applied overnight at room temperature. The sections were washed and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA and Molecular probes, Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Stained sections were mounted with prolong Gold with DAPI (Invitrogen). For lysotracker-fluorescence microscopy, dissociated neurospheres were seeded on laminin/poly-L-ornithine slides and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in medium containing 200-nM Lysotracker (DND-99, Invitrogen). TIRFM of live lysotracker-labeled neurospheres was performed with a Marianas imaging system (Intelligent Imaging Innovations/3i) consisting of a Carl Zeiss 200M motorized inverted microscope and TIRF illuminator (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) and a DPSS 561 nm laser (Cobolt). Images were acquired with a Zeiss Alpha Plan-Fluar 100 × 1.45 NA objective on a CoolSNAP HQ 2 CCD camera (Photometrics), using SlideBook 4.2 software (3i). Confocal on lysotracker-stained live cells and immunofluorescence on brain sections was performed with an inverted microscope equipped with a C1Si confocal system. Lysosomes and TAMRA-Aβ1–42 were identified as objects and counted in more than 10 TIRFM images.

Electron microscopy

For the ultrastructural studies, hippocampi were fixed and embedded using standard protocols and sections (600–900 Å) were stained in grids and visualized using a JEOL:-JEM 1200EX II Electron Microscope and a Gatan 782 Digital Camera.

Vector production

The scAAV2/8-CMV-PPCA (PPCA) and scAAV2/8-CMV-NEU1 (NEU1) constructs contain a Cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, which ensures expression of the 1.44-kb human PPCA cDNA and 1.247-kb human NEU1 cDNA. The scAAV vector particles were made in the Children’s (GMP) Good Manufacturing Practice, LLC facility on the St. Jude campus. scAAV2/8-CMV-PPCA and scAAV2/8-CMV-NEU1 vector genome titers were determined by qPCR and/or direct loading and electrophoresis of detergent-treated vector particles on native agarose gels, staining with fluorescent dye, quantitation of signal relative to known mass standards.

AAV transduction in vitro and in vivo

Neuro2a cells were transduced with 5000 genome-containing particles (GC) of scAAV2/8-CMV-PPCA and 1700 GC of scAAV2/8-CMV-NEU1 either alone or in combination in 500 μl of Optimem (Invitrogen). After 90 min incubation with vectors, complete culture medium was added to the cells that were grown for 2 days. Cell pellets from not-transduced and transduced cells were used for NEU1 enzymatic activity assays. For the transduction in vivo, 5XFAD mice (4-5-6 months old) (n= 2 for each age) were anesthetized and placed into a Kopf stereotaxic device. Injections were done unilaterally into the left hippocampus. Injections were performed with a 10-μl Hamilton syringe fitted with a glass micropipette. 10μl of virus (mixture of 2× 1011 PPCA GC and 0.7 × 1011 NEU1 GC) or 10μl of carrier solution per brain. For all the brain injections, the needle was left in place for 5 min prior to withdrawal from the brain. 4 weeks after the injection mice were sacrificed and brains were processed for amyloid (4G8 antibody), NEU1 and PPCA stainings.

Amyloid counts

Quantification of β-amyloid plaques was carried out on IHC images captured from sections stained with anti-APP/Aβ antibody (4G8 antibody). IHC images were first transformed to monochrome and inverted to make amyloid plaques bright areas. Sections of each mouse brain were imaged and the areas and densities of the plaques present in the subiculum, dentate gyrus areas were measured using NIS-Elements 3.22.11 software (Nikon Instruments, Inc. Melville, NY). An intensity threshold level was established to discriminate between plaque immunostating and background labeling. The threshold for detection was held constant throughout the image quantification. An object of interest was defined by its surface and its brightness.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were evaluated using the Student’s t-test for unpaired samples. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor William Klunk, University of Pittsburg, for the generous gift of Methoxy XO4, Dr Charles Sherr for providing the Arf−/− mice and Dr Gerard Grosveld for insightful discussions. We thank Yvan Campos for help with the graphic work and Angela McArthur for her editorial work. We also thank Dr John Gray of Vector Development Core for producing the AAV vectors, and the Veterinary Pathology and Cell and Tissue Imaging Cores for technical assistance. A.d’A. holds the Jewelers for Children Endowed Chair in Genetics and Gene Therapy. This work was funded in part by NIH grants GM60905 and DK52025, the Assisi Foundation of Memphis, the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) and the National Tay-Sachs & Allied Disease Association (NTSAD).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.d’A. supervised the research. I.A. and A.d’A. designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. I.A., A.P. and D.H. performed experiments. H.H. performed surgeries and AAV injections. S.M. obtained and processed confocal images. E.G. maintained the animal colony and collected CSF samples. R.N. provided reagents and intellectual inputs. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the scientific discussion.

Competing financial Interests: A.d’A. and I.A. are named as co-inventors on the patent application “Methods and compositions to detect the level of lysosomal exocytosis activity and methods of use”, number PCT/US2012/052629 based, in part, on the research reported herein. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Merlini G, Bellotti V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:583–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. 2012;148:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran L, Annaert W. Membrane trafficking pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Traffic. 2012;13:759–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C, Kaether C, Thinakaran G, Sisodia S. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006270. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su Y, Chang PT. Acidic pH promotes the formation of toxic fibrils from beta-amyloid peptide. Brain Res. 2001;893:287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood SJ, Maleeff B, Hart T, Wetzel R. Physical, morphological and functional differences between ph 5.8 and 7.4 aggregates of the Alzheimer’s amyloid peptide Abeta. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:870–877. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu X, et al. Amyloid seeds formed by cellular uptake, concentration, and aggregation of the amyloid-beta peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20324–20329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911281106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Smith IF, Green KN, LaFerla FM. A dynamic relationship between intracellular and extracellular pools of Abeta. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:184–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cataldo AM, et al. Abeta localization in abnormal endosomes: association with earliest Abeta elevations in AD and Down syndrome. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SJ, Lim HS, Masliah E, Lee HJ. Protein aggregate spreading in neurodegenerative diseases: problems and perspectives. Neurosci Res. 2011;70 doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brundin P, Melki R, Kopito R. Prion-like transmission of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:301–307. doi: 10.1038/nrm2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nath S, et al. Spreading of neurodegenerative pathology via neuron-to-neuron transmission of beta-amyloid. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8767–8777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajendran L, et al. Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11172–11177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vingtdeux V, et al. Alkalizing drugs induce accumulation of amyloid precursor protein byproducts in luminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18197–18205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellingham SA, Guo BB, Coleman BM, Hill AF. Exosomes: vehicles for the transfer of toxic proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases? Front Physiol. 2012;3:124. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Gonzalez R, Gauthier SA, Kumar A, Levy E. The exosome secretory pathway transports amyloid precursor protein carboxyl-terminal fragments from the cell into the brain extracellular space. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:43108–43115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nixon RA, Cataldo AM, Mathews PM. The endosomal-lysosomal system of neurons in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: a review. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:1161–1172. doi: 10.1023/a:1007675508413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funk KE, Kuret J. Lysosomal fusion dysfunction as a unifying hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:752894. doi: 10.1155/2012/752894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, et al. Endolysosome mechanisms associated with Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in rabbits ingesting cholesterol-enriched diet. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:1289–1303. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA. Primary lysosomal dysfunction causes cargo-specific deficits of axonal transport leading to Alzheimer-like neuritic dystrophy. Autophagy. 2011;7:1562–1563. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.12.17956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cataldo AM, Paskevich PA, Kominami E, Nixon RA. Lysosomal hydrolases of different classes are abnormally distributed in brains of patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:10998–11002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nixon RA, Cataldo AM. Lysosomal system pathways: genes to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:277–289. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nixon RA. Autophagy, amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer disease. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4081–4091. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staretz-Chacham O, Lang TC, LaMarca ME, Krasnewich D, Sidransky E. Lysosomal storage disorders in the newborn. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1191–1207. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidransky E, Lopez G. The link between the GBA gene and parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:986–998. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70190-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzulli JR, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and alpha-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. 2011;146:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.d’Azzo A, Bonten E. Molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis in a glycosphingolipid and a glycoprotein storage disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:1453–1457. doi: 10.1042/BST0381453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonten EJ, d’Azzo A. Lysosomal neuraminidase. Catalytic activation in insect cells is controlled by the protective protein/cathepsin A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37657–37663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yogalingam G, et al. Neuraminidase 1 is a negative regulator of lysosomal exocytosis. Dev Cell. 2008;15:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stinchcombe J, Bossi G, Griffiths GM. Linking albinism and immunity: the secrets of secretory lysosomes. Science. 2004;305:55–59. doi: 10.1126/science.1095291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca(2+)-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell. 2001;106:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Geest N, et al. Systemic and neurologic abnormalities distinguish the lysosomal disorders sialidosis and galactosialidosis in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1455–1464. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.12.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowden JA, O’Brien JS. Sialidosis: a review of human neuraminidase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1979;31:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meikle PJ, et al. Diagnosis of lysosomal storage disorders: evaluation of lysosome-associated membrane protein LAMP-1 as a diagnostic marker. Clin Chem. 1997;43:1325–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karageorgos LE, et al. Lysosomal biogenesis in lysosomal storage disorders. Exp Cell Res. 1997;234:85–97. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zanoteli E, et al. Muscle degeneration in neuraminidase 1-deficient mice results from infiltration of the muscle fibers by expanded connective tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:659–672. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaiswal JK, Andrews NW, Simon SM. Membrane proximal lysosomes are the major vesicles responsible for calcium-dependent exocytosis in nonsecretory cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:625–635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamijo T, et al. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell. 1997;91:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, et al. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1136–1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Utikal J, et al. Immortalization eliminates a roadblock during cellular reprogramming into iPS cells. Nature. 2009;460:1145–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature08285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hahn CN, et al. Generalized CNS disease and massive GM1-ganglioside accumulation in mice defective in lysosomal acid beta-galactosidase. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:205–211. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Irvin DK, Dhaka A, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Kornblum HI. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors governing cell fate in cortical progenitor cultures. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:162–172. doi: 10.1159/000072265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klunk WE, et al. Imaging Abeta plaques in living transgenic mice with multiphoton microscopy and methoxy-X04, a systemically administered Congo red derivative. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:797–805. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.9.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:532–540. doi: 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haass C, Koo EH, Mellon A, Hung AY, Selkoe DJ. Targeting of cell-surface beta-amyloid precursor protein to lysosomes: alternative processing into amyloid-bearing fragments. Nature. 1992;357:500–503. doi: 10.1038/357500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagawa K, et al. Sialylation enhances the secretion of neurotoxic amyloid-beta peptides. J Neurochem. 2006;96:924–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oakley H, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu H, et al. Preclinical dose-finding study with a liver-tropic, recombinant AAV-2/8 vector in the mouse model of galactosialidosis. Mol Ther. 2011;20:267–274. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong E, Cuervo AM. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nn.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang L, Sheng R, Qin Z. The lysosome and neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41:437–445. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cole SL, Vassar R. The Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eisele YS, et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330:980–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1194516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klug GM, et al. Beta-amyloid protein oligomers induced by metal ions and acid pH are distinct from those generated by slow spontaneous ageing at neutral pH. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:4282–4293. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nixon RA. Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cirrito JR, et al. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrachina M, Maes T, Buesa C, Ferrer I. Lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;32:505–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hashimoto T, et al. Age-dependent increase in lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 and early-onset behavioral deficits in APPSL transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;469:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:77sr71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63:287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cramer PE, et al. ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science. 2012;335:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1217697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nathwani AC, et al. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2357–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.