The CTCF protein functions as an insulator and higher-order chromatin organizer. Reinberg and colleagues report that in addition to its DNA-binding activity, CTCF binds RNA. They map the RNA-binding domain and demonstrate that apart from its established role at the p53 promoter, CTCF regulates p53 expression through its physical interaction with the Wrap53 RNA. Furthermore, the authors show that the RNA-binding domain facilitates CTCF multimerization in an RNA-dependent manner, which may bear directly on its role in establishing higher-order chromatin structures.

Keywords: CTCF, RNA binding, Wrap53, p53, multimerization

Abstract

The multifunctional CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) protein exhibits a broad range of functions, including that of insulator and higher-order chromatin organizer. We found that CTCF comprises a previously unrecognized region that is necessary and sufficient to bind RNA (RNA-binding region [RBR]) and is distinct from its DNA-binding domain. Depletion of cellular CTCF led to a decrease in not only levels of p53 mRNA, as expected, but also those of Wrap53 RNA, an antisense transcript originated from the p53 locus. PAR-CLIP-seq (photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation [PAR-CLIP] combined with deep sequencing) analyses indicate that CTCF binds a multitude of transcripts genome-wide as well as to Wrap53 RNA. Apart from its established role at the p53 promoter, CTCF regulates p53 expression through its physical interaction with Wrap53 RNA. Cells harboring a CTCF mutant in its RBR exhibit a defective p53 response to DNA damage. Moreover, the RBR facilitates CTCF multimerization in an RNA-dependent manner, which may bear directly on its role in establishing higher-order chromatin structures in vivo.

The CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is a remarkably versatile, ubiquitous, and highly conserved zinc finger (ZF) protein (Phillips and Corces 2009). It was originally identified after thorough analyses of factors binding to the chicken c-myc gene promoter (Lobanenkov et al. 1986), later purified (Lobanenkov et al. 1990), and described initially as a transcription factor (Filippova et al. 1996). Since then, CTCF has been implicated in diverse cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, alternative splicing, insulation, imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and higher-order chromatin organization (Phillips and Corces 2009; Holwerda and de Laat 2013). Genome-wide association studies have identified a large number of CTCF-binding sites scattered across the genome, and these sites map to promoters, enhancers, and intergenic regions as well as within gene bodies (Martin et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2012). The associations of CTCF with its DNA target sites as well as with its interacting proteins are thought to contribute to CTCF multifunctionality (Ohlsson and Renkawitz 2001).

Among the various genomic CTCF target sites is the gene encoding the tumor suppressor protein p53. p53 is a sequence-specific transcription factor essential in the cellular response to DNA damage and other types of cellular stress (Vousden and Prives 2009). Contingent on the level of DNA damage, p53 can initiate signaling pathways toward cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis to avoid oncogenic transformation (Vousden and Prives 2009). Expression of the p53 gene is regulated by the interplay of a number of transcription factors, microRNAs (miRNAs), the ZF protein CTCF, and its natural antisense transcript, Wrap53 (Mahmoudi et al. 2009; Saldaña-Meyer and Recillas-Targa 2011). p53 transcription levels are maintained through CTCF binding to the p53 gene promoter region, allowing for an open chromatin conformation (Soto-Reyes and Recillas-Targa 2010), and upon DNA damage, Wrap53 RNA is essential for induction of p53 gene expression (Mahmoudi et al. 2009). Wrap53 RNA is an antisense transcript originated from the p53 locus that positively regulates p53 mRNA levels and, upon DNA damage, is essential for induction of p53 gene expression (Mahmoudi et al. 2010). The Wrap53 gene lies upstream of the p53 gene on the opposite strand and comprises three different transcriptional start sites (TSSs), termed α, β, and γ (see Fig. 1A). Only transcripts originated from exon 1α that directly overlap the first exon of p53 were found to positively regulate p53 (Mahmoudi et al. 2009). Wrap53 can also be translated into protein that was found to be an essential component for Cajal body maintenance (Mahmoudi et al. 2010). Of note, as opposed to Wrap53 RNA, its protein has not been implicated in p53 regulation.

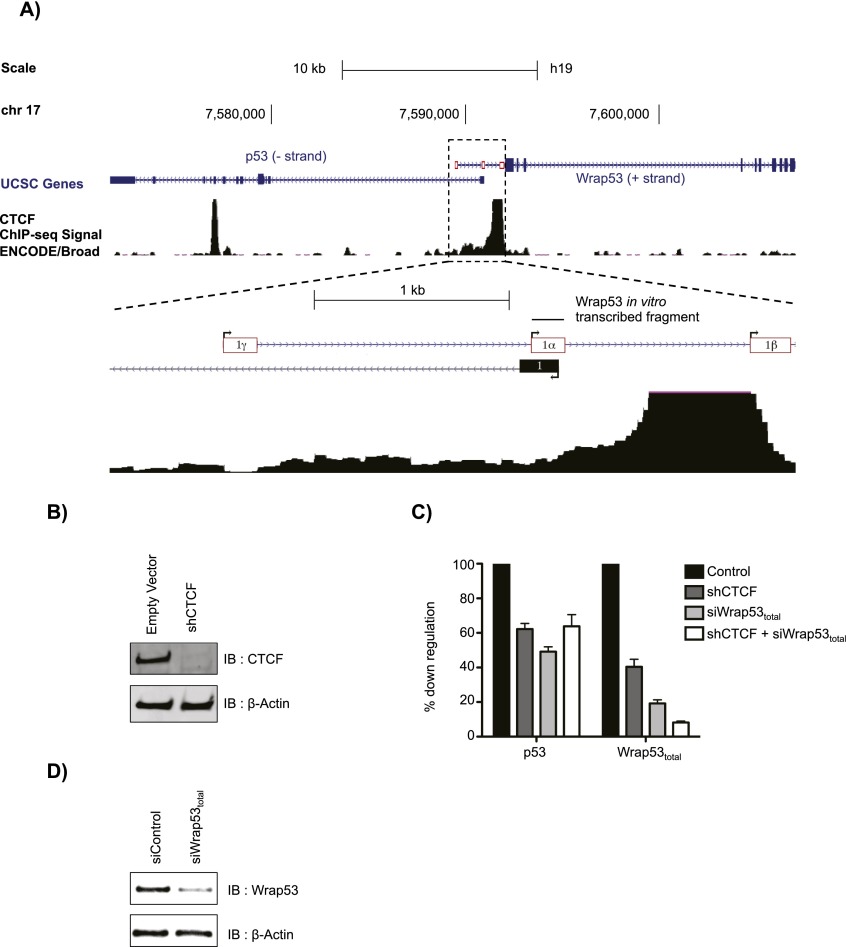

Figure 1.

CTCF is required for regulation of the p53/Wrap53 locus. (A) Genomic organization of the p53/Wrap53 locus. (B) Immunoblot after shRNA-mediated knockdown of CTCF or with empty vector (control) in U2OS cells. β-Actin served as loading control. (C) RNA was quantified by RT-qPCR after knockdown, as indicated, and normalized to GAPDH levels and is shown as percentage down-regulation. Bars indicate the mean of three biological replicates + SEM. (D) As in B, but with siRNA-mediated knockdown of Wrap53 or siControl.

Here, we report that apart from its established DNA-binding activity, CTCF also has an intrinsic ability to bind RNA. We mapped a domain within CTCF that is necessary and sufficient to bind RNA and is distinct from that required for DNA binding. Depletion of cellular CTCF led to a decrease in not only levels of p53 mRNA, as expected, but also those of Wrap53. With this basis, we addressed the relationship between CTCF and Wrap53 in regulating human p53 gene expression as well as the role of RNA in CTCF multimerization.

Results

CTCF is required for regulation of the p53/Wrap53 locus

The human p53 gene is mutated in ∼50% of tumors (National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program, http://seer.cancer.gov). However, a large number of tumors carry wild-type p53, suggesting that its expression can be disrupted by other mechanisms. Since the CTCF-binding site that lies in the p53 gene promoter corresponds to the first intron of Wrap53 on the opposite strand (Fig. 1A), we hypothesized that CTCF regulates the transcription of both p53 and Wrap53 genes through binding to its regulatory element and, possibly, to the antisense transcript Wrap53. Upon stable expression of a shRNA against CTCF, resulting in reduced CTCF levels (Fig. 1B), transcripts for p53 and all Wrap53 isoforms (Wrap53total) were decreased, based on normalization with the constitutively expressed GAPDH gene (Fig. 1C). Similar decreases were observed with an inducible shRNA targeting the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of CTCF after 72 h of induction (data not shown). Interestingly, p53 expression was also down-regulated when the antisense transcript Wrap53total was depleted using siRNAs (Fig. 1C,D; Mahmoudi et al. 2009), and depletion of both CTCF and Wrap53total had similar effects (Fig. 1C), suggesting that transcriptional regulation of sense and antisense RNAs at this locus is tightly coregulated by CTCF.

CTCF binds a variety of RNAs in vivo, including Wrap53

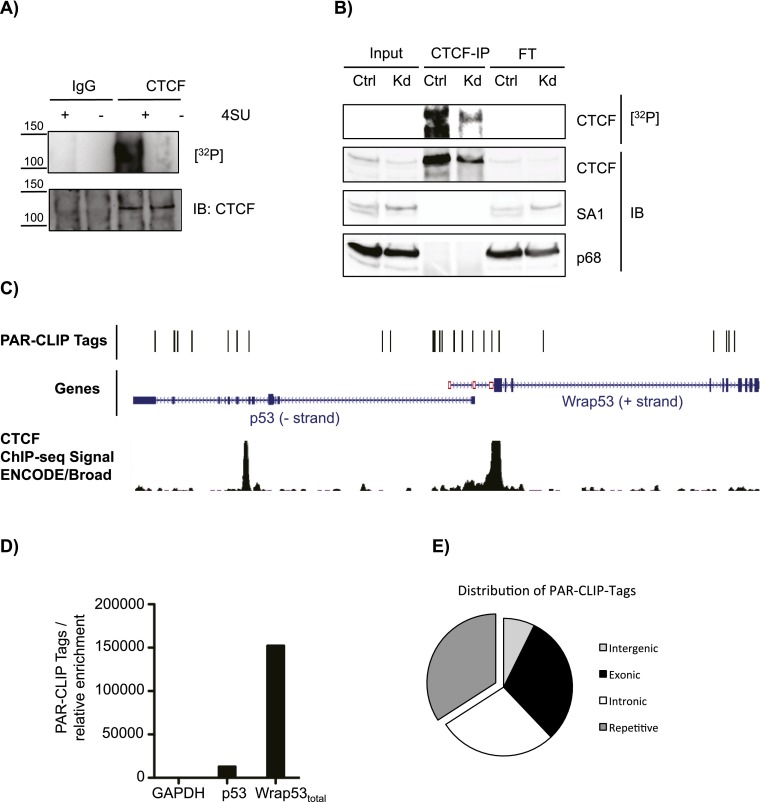

As depletion of either CTCF or Wrap53total gave rise to similar effects, we hypothesized that these two species may be not only functionally but also physically related. To determine whether Wrap53 RNA is associated with CTCF in vivo, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) followed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Consistent with our hypothesis, both p53 and the Wrap53total transcripts were enriched in CTCF-specific RIPs compared with IgG (Supplemental Fig. S1A,B). Moreover, Wrap53total RNA bound specifically to CTCF, as compared with the case of SCML2 (Supplemental Fig. S1A,B), an unrelated protein that also binds RNA in the nucleus (R Bonasio, E Lecona, and D Reinberg, unpub.). Although we observed some enrichment for the Wrap53total RNA using SCML2 as a control, native RIP can yield false positives due to RNA–protein reassociations after cell lysis (Mili and Steitz 2004; Riley et al. 2012). Given these limitations, we reassessed specific and direct binding of Wrap53 to CTCF using an unbiased genome-wide approach involving the PAR-CLIP (photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation) assay, which makes use of a photoactivatable nucleoside analog, 4-thiouridine (4-SU), to selectively and irreversibly cross-link protein to RNA in living cells (Hafner et al. 2008). To avoid possible contamination from other RNA-binding proteins with molecular weights similar to that of CTCF, we performed immunoprecipitations with a buffer containing a zwitterionic detergent, 2% lauryldimethylbetaine, that preserves antibody reactivity while significantly decreasing coprecipitation of CTCF protein partners, such as the DEAD-box RNA helicase p68 (DDX5) and the SA1 subunit of the cohesin complex (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S2C; Yao et al. 2010; Xiao et al. 2011). We concluded that the radioactive signal obtained was due to RNA specifically cross-linked to CTCF, since it was dependent on the presence of 4-SU in the culture medium (Fig. 2A), was decreased upon CTCF knockdown (Fig. 2B), and was sensitive to RNase treatment (Supplemental Fig. S1C,D). Of note, the preparation of cells for PAR-CLIP seems to result in the partial degradation of full-length (FL) CTCF given the presence of lower-molecular-weight species that are detected with an antibody against CTCF and are diminished upon CTCF knockdown (Supplemental Fig. S1D and Fig. 2B, respectively).

Figure 2.

CTCF binds a variety of RNAs in vivo, including Wrap53. (A) PAR-CLIP (top) and immunoblot for CTCF (bottom) in U2OS cells with (+) or without (−) 4-SU incorporation. Whole nuclear lysates were immunoprecipitated with a CTCF antibody or IgG. (B) PAR-CLIP (top) and immunoblots (bottom) for CTCF, DDX5, or SA1 using the same membrane. Immunoprecipitation was performed using an antibody against CTCF in whole nuclear extracts from cells stably transfected with a control shRNA (Ctrl) or shRNA against CTCF (Kd). (C) Genome browser view showing PAR-CLIP tags recovered after deep sequencing over the p53/Wrap53 locus. The CTCF ChIP-seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation [ChIP] combined with deep sequencing) signal from ENCODE is also shown. (D) Graphical representation of normalization of PAR-CLIP tags versus the average relative enrichment obtained by qPCR. (E) Pie chart showing the genome-wide distribution of PAR-CLIP tags.

To identify the RNAs bound to CTCF in vivo, the 32P-labeled species corresponding to FL CTCF were excised from the PAR-CLIP membrane, with the cross-linked RNA being eluted and prepared to construct libraries for deep sequencing. We obtained ∼1.2 × 106 unique PAR-CLIP tags in each biological replicate. Although p53 is expressed at low levels and Wrap53 RNA is much less abundant than p53 mRNA, we obtained PAR-CLIP tags from both Wrap53 α and β TSSs, confirming our initial observations of CTCF interaction with Wrap53 RNA (Fig. 2C). When the average relative enrichment of p53 and Wrap53total transcripts, normalized to those of GAPDH obtained by qPCR, was compared with the PAR-CLIP tags obtained from the two biological replicates, we observed a clear enrichment for Wrap53total over p53 and GAPDH (Fig. 2D). We then inspected the genome-wide distribution of the PAR-CLIP tags and found that ∼34% were located at repetitive regions, 30% were located at exons, 28% were located at introns, and 8% were located at intergenic regions (Fig. 2E). There was no significant enrichment for either exonic or intronic reads, indicating that CTCF binds to both nascent and mature transcripts. Using an arbitrary cutoff of five unique PAR-CLIP tags, the data set comprised 17,201 genes, of which 71% are protein-coding, 12% are pseudogenes, 8.3% are antisense, 5% are lincRNAs, and 3.7% accounted for other types (Supplemental Table S1). Thus, Wrap53total RNA is recovered in both native RIP and PAR-CLIP using an antibody against CTCF. The latter analysis provides the first evidence of CTCF binding to transcripts genome-wide.

Identification and mapping of the RNA-binding region (RBR) of CTCF

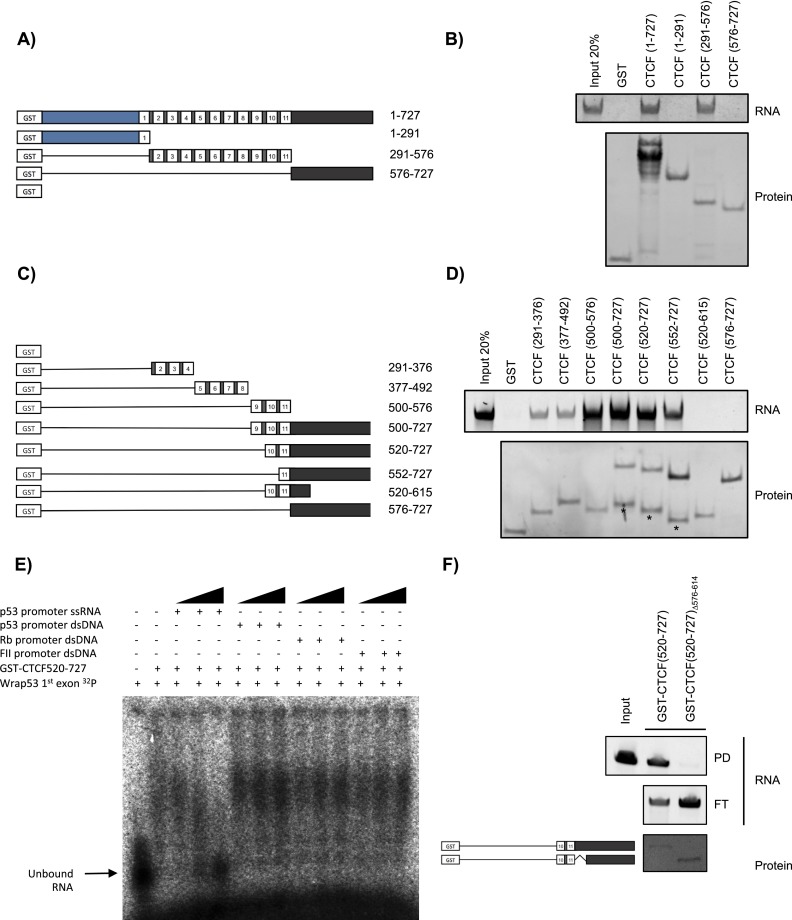

Given the data collected on RNA binding to CTCF in vivo, we next sought to identify the domain of CTCF required for such interaction. Candidates of CTCF, either FL or deletion mutants, were fused to the human glutathione S-transferase domain (GST), purified from Escherichia coli, and then incubated with RNA transcribed in vitro from a 5′-terminal Wrap53 template spanning nucleotides 1–167 of exon 1α (Fig. 1). RNA-binding activity was evident from the ZF domain but not from the terminal regions alone (Fig. 3A,B). More detailed mapping demonstrated that ZFs 9–11 exhibit a higher affinity for the RNA than the remaining ZFs (Fig. 3C,D). Finally, systematic deletion of ZFs 9–11 revealed that the optimal region for RNA binding spans amino acids 520–727 and includes ZFs 10–11 and the C-terminal region, henceforth termed the RBR (Fig. 3C,D). While the C terminus alone (576–727 amino acids) was ineffectual in binding, the deletion mutant (520–615 amino acids) lacking most of the C terminus but containing ZFs 10–11 was also ineffectual (Fig. 3C,D), suggesting that, although not sufficient, the C terminus is required for RNA binding.

Figure 3.

Identification and characterization of the CTCF RBR. (A,C) Schematic representations of GST-tagged CTCF, either FL or deletion mutant versions, analyzed as shown in B and D, respectively. (B,D) RNA-binding assay showing recovered RNA stained with SYBR Gold (top panel) and recovered protein stained with SYPRO Red (bottom panel). In D, the asterisk demarcates degraded protein. (E) EMSA using GST-CTCF520–727 and a radioactive 5′ probe spanning nucleotides 1–167 of Wrap53 mRNA incubated with increasing amounts of unlabeled DNA or RNA, as indicated. (F) As in B and D but with GST-CTCF520–727 or GST-CTCF(520–727)Δ576–614. (PD) Pull-down; (FT) flow through.

We next tested the RBR for DNA versus RNA-binding preferences using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). Binding of GST-RBR to a probe containing the first Wrap53 exon was compared in the presence of increasing amounts of RNA or DNA (Fig. 3E). Each of the competing DNAs comprised a distinct CTCF-binding site, as demonstrated previously in EMSA: the CTCF-binding site located in the p53 gene promoter (Soto-Reyes and Recillas-Targa 2010), the CTCF-binding site in the human Rb gene promoter (De La Rosa-Velázquez et al. 2007), and the chicken cHS4 β-globin insulator FII (Valadez-Graham et al. 2004). The RNA competitor was derived by in vitro transcription from the p53 promoter region described above. While addition of this p53-derived RNA successfully competed GST-RBR binding to the probe containing the Wrap53 exon, all of the DNA candidates containing a CTCF-binding site were ineffectual (Fig. 3E). To help pinpoint a specific region of CTCF that is necessary for RNA binding, we took advantage of the RNABindR software that is designed to predict putative RBRs (Terribilini et al. 2007). The software predicted with high sensitivity and specificity that the region of the C terminus downstream from the last ZF could bind RNA. Indeed, deletion of residues 576–614 within the predicted region drastically decreased binding to RNA, as demonstrated by RNA-binding assays (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that CTCF contains a previously unrecognized RBR that displays strong binding preferences for p53 and Wrap53 RNAs in vitro.

An internal deletion within the RBR disturbs the DNA damage response

To address the functional relevance of Wrap53 RNA–CTCF interactions in vivo, we generated an inducible cell system in which endogenous CTCF is depleted by shRNA knockdown and the CTCF-deficient cells are rescued with HA-tagged versions of CTCF, either wild type (HA-CTCFwt) or mutant in RNA binding (HA-CTCFΔ576–614) (Supplemental Fig. S2). Of note, a putative nuclear localization signal is found within 576–614 amino acids of CTCF, specifically in amino acids 590–603 (Klenova et al. 2001). Nonetheless, the Δ576–614 deletion did not affect the ability of CTCF to localize to the nucleus in vivo or its general association to chromatin or to the known interacting proteins DDX5 and the SA1 subunit of the cohesin complex (Supplemental Fig. S2A–C; Yao et al. 2010; Xiao et al. 2011). Furthermore, recombinant forms of both HA-CTCFwt and HA-CTCFΔ576–614 were able to evict the residual endogenous CTCF from the chromatin fraction after inducing knockdown for 72 h with doxycycline treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2D).

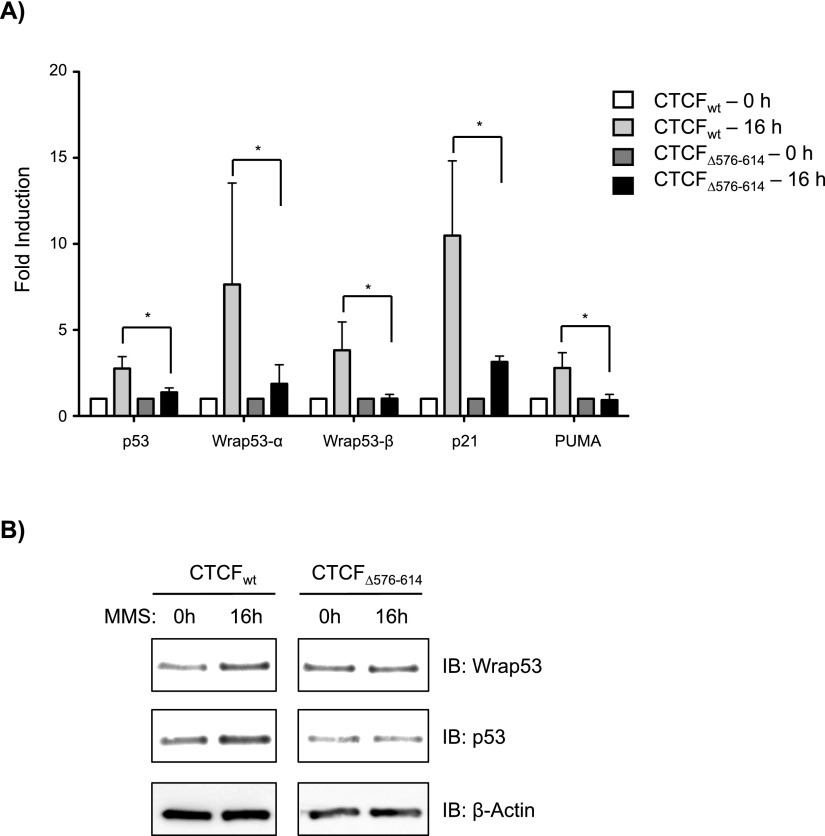

Mahmoudi et al. (2009) reported that both Wrap53 and the p53 transcripts were induced upon DNA damage. They also suggested that Wrap53 not only maintains p53 mRNA levels but also plays a role in stabilizing p53 mRNA in response to DNA damage (Mahmoudi et al. 2009). To ascertain whether a complex between CTCF and Wrap53 RNA regulates p53 expression, cell lines harboring HA-CTCFwt or HA-CTCFΔ576–614 were induced with doxycycline for 56 h and then treated for an additional 16 h with doxycycline along with the DNA-damaging drug methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). Consistent with the previous study (Mahmoudi et al. 2009), cells rescued with HA-CTCFwt exhibited up-regulation of both p53 and α and β isoforms of Wrap53 at the mRNA level as well at the protein level after DNA damage treatment (Fig. 4A,B, respectively). Furthermore, genes involved in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the p53 pathway (p21 and PUMA, respectively) were also up-regulated (Fig. 4A). In contrast, cells induced for expression of the mutant, RNA-binding-defective HA-CTCFΔ576–614 failed to rescue these mRNA and protein levels upon DNA damage (Fig. 4). Of note, knockdown of Wrap53total did not affect the recruitment of endogenous CTCF to the p53 promoter (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Furthermore, when used in the rescue experiment, HA-CTCFΔ576–614 did not exhibit a defect in binding to the p53 promoter (Supplemental Fig. S3B) or in the endogenous mRNA levels of p53 or Wrap53 (Supplemental Fig. S3C) but did show a decreased coprecipitation with Wrap53total (Supplemental Fig. S3D,E), highlighting the relevancy of its defect during conditions of DNA damage. Thus, a CTCF mutant defective in RNA binding cannot restore features of the DNA damage response in CTCF-depleted cells, likely due to its failure to bind Wrap53 RNA, thereby preventing transcriptional induction of the p53 locus.

Figure 4.

Deletion of the RBR within CTCF disturbs the DNA damage response. Cell lines containing HA-CTCFwt or HA-CTCFΔ576–614 were induced with doxycycline for 56 h and then treated for an additional 16 h with doxycycline with or without the DNA-damaging drug MMS, as indicated. (A) RT-qPCR for the transcripts indicated, shown as fold induction and normalized to GAPDH levels. Bars indicate the mean of three biological replicates + SEM. (*) P < 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U-test. (B) Immunoblot of p53 and Wrap53, with β-actin as loading control.

RNA aids in the formation of CTCF multimers

We speculated that RNA–CTCF interactions might participate in the formation of higher-order multimers of CTCF by bridging the interaction between monomers. CTCF has many binding partners (Zlatanova and Caiafa 2009), including other CTCF molecules (Valadez-Graham et al. 2004; Yusufzai et al. 2004), although the molecular basis underlying such dimerization/multimerization has not been reported. Because modulation of CTCF multimerization through RNA might have major implications in chromatin looping and interaction with diverse cofactors, we tested the ability of CTCF to dimerize or multimerize in the presence of different nucleases.

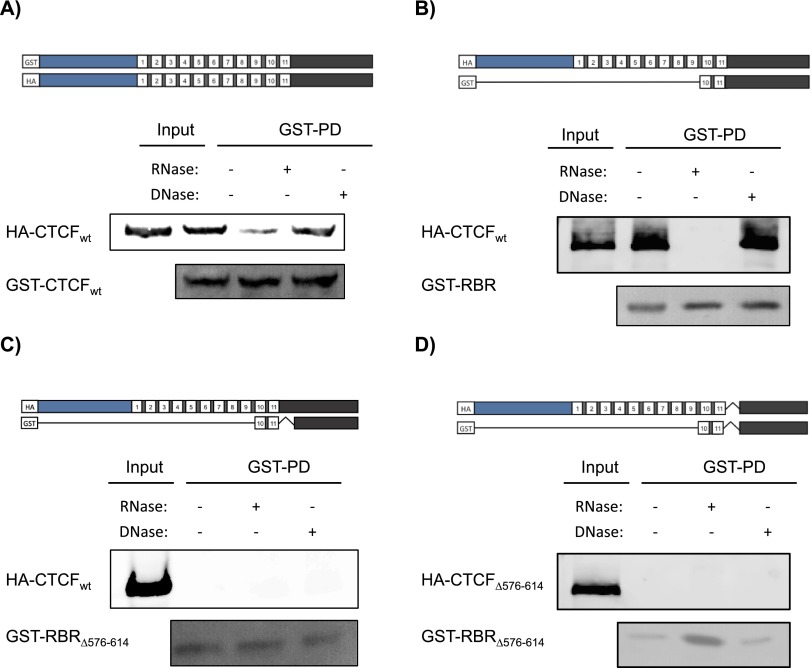

To this end, we took advantage of distinctly tagged versions of CTCF. We first tested the ability of FL proteins to interact with each other. Recombinant GST-CTCFwt purified from E. coli was added to nuclear extracts derived from the expressing HA-CTCFwt cell line, as a function of DNase or RNase treatment, and then analyzed in pull-down assays. Indeed, GST-CTCFwt could coprecipitate HA-CTCFwt (Fig. 5A). However, the addition of RNase during the incubation period led to an ∼50% decrease in the amount of HA-CTCFwt coprecipitated, compared with the untreated case; this decrease was not observed with DNase addition (Fig. 5A). The RBR is sufficient for this dimerization, since incubation with GST-RBR also gave rise to efficient coprecipitation of HA-CTCFwt, while the addition of RNase also thwarted HA-CTCFwt recovery in this case, and DNase treatment was again ineffectual (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the ability to interact with RNA was required for the observed CTCF dimerization/multimerization, as evidenced by the absence of such interaction in the case of the mutant, RNA-binding-defective GST-RBRΔ576–614 incubated with either HA-CTCFwt or HA-CTCFΔ576–614, (Fig. 5C,D, respectively).

Figure 5.

RNA facilitates CTCF dimerization/multimerization. (A–D) Shown at the top of each panel are schematic representations of CTCF, either wild type (WT) or mutant (CTCFΔ576–614), or its RBR, either wild type or mutant (RBRΔ576–614), tagged with HA or GST, as indicated. Below are the respective results of GST pull-down experiments performed using nuclear extracts of U2OS cells expressing either HA-CTCFwt or HA-CTCFΔ576–614, in the presence or absence of nucleases, as indicated. GST-CTCF proteins were stained with Ponceau Red, and HA-CTCF proteins were detected with an antibody against HA.

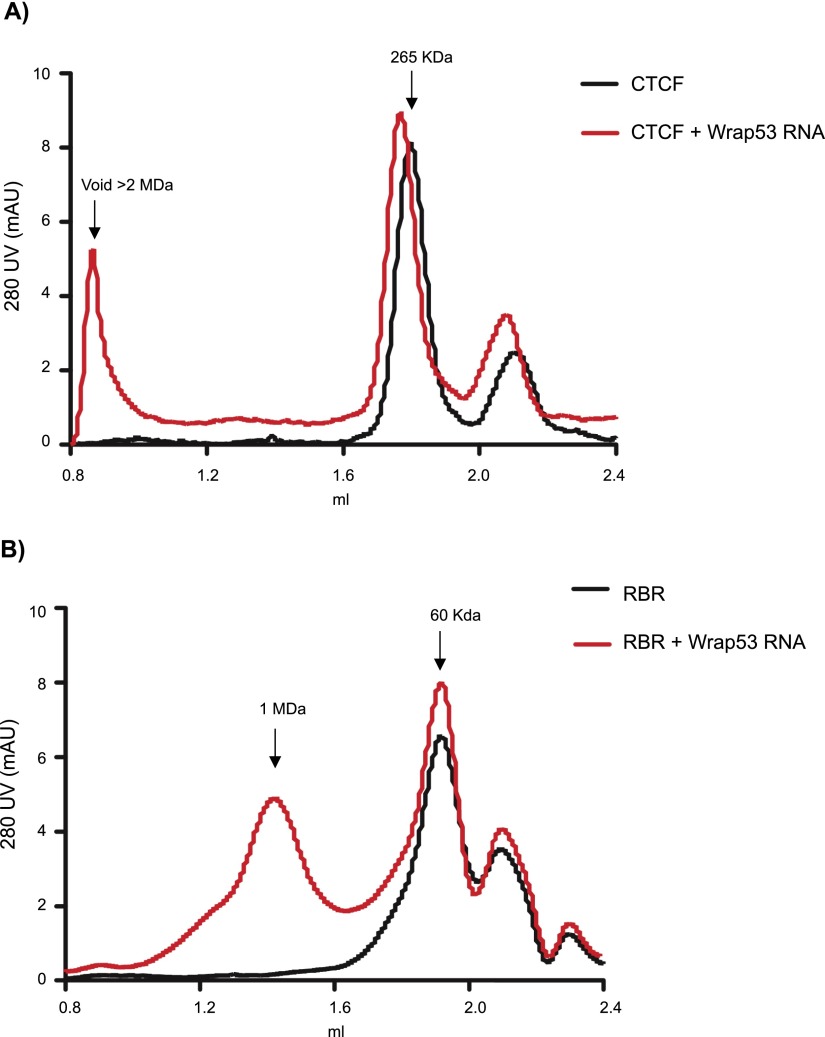

To corroborate this observation, we removed the GST tag from the CTCFwt and performed size exclusion chromatography in the presence or absence of 167 base pairs (bp) of Wrap53 RNA. The elution profile of the CTCF sample alone peaked at an apparent mass of 265 kDa, which would point to the formation of a trimer (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the elution profile in the presence of Wrap53 RNA suggested the formation of a complex >2 MDa (Fig. 6A). Lending further support to the conclusion that RNA helps CTCF multimerization via its RBR, the elution profile of the RBR fragment (∼22 kDa) alone peaked at ∼60 kDa but was shifted to 1 MDa in the presence of Wrap53 RNA (Fig. 6B). In the latter case, the RBR and RNA profiles strongly indicated their coelution, with all of the RNA being found in complex with RBR, migrating at a significantly higher molecular weight than that predicted for RBR (Fig. 6B) or RNA alone (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that RNA aids in the formation of multimers of CTCF through its RBR.

Figure 6.

CTCF–Wrap53 RNA forms large-molecular-weight complexes. Purified CTCF, either FL (A) or the RBR (B) domain, was fractionated in a Superose 6 sizing column in the presence or absence of Wrap53 RNA.

Discussion

Our findings support the role of RNA binding as an important, additional regulatory function among the spectrum of those already recognized for CTCF. As shown here, CTCF binding to Wrap53 is integrally related to the appropriate p53 transcriptional response to DNA damage. We also presented the first genome-wide array of CTCF-interacting transcripts that may provide insights into the scope of CTCF targets as well as the mechanistic basis for CTCF action. Our findings suggest a general function for such CTCF–RNA interaction in mediating CTCF multimerization that may bear directly on the role of CTCF in chromatin looping.

We previously determined that loss of CTCF binding to target DNA sequences promotes epigenetic silencing of p53 gene expression through enrichment of repressive chromatin marks in its regulatory region (Soto-Reyes and Recillas-Targa 2010). Knockdown of Wrap53 was reported by another group as leading to down-regulation of p53 (Mahmoudi et al. 2009). These initial observations provided insights into the regulation of the p53 locus. Here, we provide an additional means by which CTCF participates in the transcriptional regulation of the human p53 gene. Our finding that CTCF knockdown down-regulates both p53 and Wrap53total mRNA levels points to an interdependent mechanism involving CTCF and Wrap53 RNA. Our hypothesis that CTCF could make direct contacts with Wrap53 RNA was supported initially by their coimmunoprecipitation and then confirmed through in vitro characterizations. Indeed, as shown here, CTCF comprises a previously unrecognized RNA-binding activity that encompasses its ZFs 10–11 and C-terminal segment independent of its well-established DNA-binding activity (Fig. 3). Nakahashi et al. (2013) reported recently that CTCF binds primarily to its DNA sequence motif with ZFs 4–7 and that its remaining ZFs have a stabilizing role. They also described that ZFs 9–11 can associate with a second conserved, upstream DNA motif at ∼15% of its sites (Nakahashi et al. 2013). This study complements our observations, as ∼85% of the CTCF proteins bound to DNA would potentially be free to make additional contacts with RNA through their RBRs as well as any unbound CTCF.

The CTCF ZF domain is almost completely conserved among mice, chickens, and humans (Ohlsson and Renkawitz 2001) and comprises 10 C2H2-type ZFs and an 11th C2HC-type ZF. Results presented here show that ZFs 10–11 specifically bind RNA. Besides CTCF, there are a number of other ZF proteins from different organisms that bind both DNA and RNA (Brown 2005). TFIIIA in mammals is a prime example, providing insight into how proteins with multiple C2H2-type ZFs can specifically bind both DNA and RNA. Similar to our findings with CTCF, TFIIIA uses different ZFs to achieve specificity between DNA and RNA, requiring ZFs 1–3 to bind DNA and its central ZFs 4–6 to bind RNA (Searles et al. 2000). TFIIIA in complex with 5S RNA was also the first ZF–RNA structure resolved, revealing that ZF binding to RNA is different from its well-studied binding to DNA (Lu et al. 2003). It is important to emphasize that these ZFs can bind both DNA and RNA and both single-stranded and double-stranded versions but with distinctive affinities (Brown 2005). Recognition of ssRNA by C2H2 ZFs is made through aromatic side chains intercalating between appropriately spaced dinucleotide bases, whereas recognition of dsDNA is through the α helix forming hydrogen bonds with the major groove bases (Brown 2005). Unlike TFIIIA, which shows high specificity for 5S RNA, our results show that, at least in vitro, CTCF recognizes RNA with little sequence specificity. Instead of dependence only on sequence specificity, CTCF–RNA contacts may arise in a context-dependent manner, perhaps favoring intricate secondary or tertiary structures that are currently not feasible to reproduce in vitro.

The results discussed above argue for CTCF making direct contacts with RNA, but the general biological relevance of this RNA-binding activity remains unclear. In the context of p53 transcriptional regulation, our evidence supports CTCF-mediated regulation of p53 and Wrap53 transcription during the DNA damage response through two different levels: (1) binding to the p53 promoter region (Soto-Reyes and Recillas-Targa 2010) and (2) interacting with Wrap53 RNA. Another specific function for CTCF was reported recently in which CTCF binds to the noncoding RNA Jpx in the context of X-chromosome inactivation (Sun et al. 2013). This group proposed that CTCF could be evicted from its binding site by Jpx overexpression. However, this interplay was not a general feature of CTCF, being restricted to an allele-specific site in the Xist locus and irrelevant to the other CTCF-binding sites tested. To date, only locus-specific functions for RNA–CTCF interactions have been supported such that the general biological significance for these interactions remains elusive.

The first role of CTCF described was that of a transcription factor (Filippova et al. 1996), and, later, a number of studies described its function as an insulator (Barkess and West 2012). Nonetheless, accumulating evidence suggests that its insulation function may occur in only a few cases, probably as a consequence of its primary role as a chromatin organizer (Handoko et al. 2011; Sanyal et al. 2012; Phillips-Cremins et al. 2013). CTCF is implicated in a myriad of functions in gene regulation, but perhaps its most crucial role is in the formation of chromatin loops (Phillips and Corces 2009). In this regard, our data support the hypothesis that RNA facilitates CTCF multimerization, as evidenced by the requirement of RNA for CTCF–CTCF interactions by pull-downs (Fig. 5) and the formation of large CTCF–Wrap53 RNA complexes using size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 6). This RNA dependence for protein multimerization has been observed in other cases as well. For example, the human cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G (A3G) was shown to oligomerize only in the presence of RNA (Huthoff et al. 2009), and, similarly, the p53 protein can interact with p68/p72 and the Drosha complex in an RNA-dependent manner (Suzuki et al. 2009). Moreover, the physical interaction of CTCF with the DEAD-box RNA-binding protein p68 (DDX5) was also shown to be dependent on its associated noncoding RNA, SRA (Yao et al. 2010). Interestingly, the investigators proposed that other RNAs might partially substitute for SRA in this context, hinting at context-dependent interactions as opposed to sequence specificity. Nonetheless, our results show that the FL CTCF treated with RNase decreased the recovery of additional CTCF molecules by only ∼50% (Fig. 5A). This observation could be due to incomplete degradation of the RNA or contributions to CTCF oligomerization by CTCF-interacting proteins.

We can conclude that the ubiquitous architectural protein CTCF binds a large array of different RNA species genome-wide. This seems to constitute a general feature for the “master weaver” of the genome. However, currently, we have insight into only two functionally different and locus-specific roles for CTCF in its interaction with Jpx (Sun et al. 2013) or Wrap53 RNA (this study). We provided some insight into the possible formation of RNA-dependent CTCF multimers that would influence nuclear organization by regulating chromatin loops, and this in turn begets new sets of questions. Are some chromatin loops formed, maintained, and regulated by CTCF–RNA interactions? Do other architectural proteins interact via RNA? What are the regulatory cues for CTCF in RNA binding? Does DNA binding precede, being required for RNA binding, or vice versa? Is RNA methylation a means of regulating its interaction with CTCF? What is the molecular basis to achieve both locus-specific and general functions? All of these are interesting questions and warrant further investigation. Finally, the biochemical characterization of the RBR within CTCF and the genome-wide description of its associated RNAs will facilitate screens for other relevant locus-specific and cell type-specific regulatory functions. The RNA-dependent multimerization of CTCF and its potential in mediating chromatin looping will likely have major implications in future research in nuclear organization and epigenetic regulation.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and oligonucleotide primers

Detailed information for antibodies and oligonucleotides used in this study is reported in Supplemental Tables S3 and S4, respectively.

Protein constructs

DNA encoding FL CTCF or CTCFΔ576–614 was cloned into the pINTA-N3 system (Kaneko et al. 2014), and expression was activated in a doxycycline-dependent manner by the rtTA transactivator contained in the pTRIPZ vector expressing a doxycycline-dependent shRNA against the 3′ UTR of CTCF (Thermo Scientific V3THS_409881). To produce GST-tagged truncated CTCF proteins in E. coli, a series of human CTCF cDNAs were PCR-amplified and cloned into pGEX6-P1.

Native RIP

Nuclear extracts were obtained using an established protocol (Dignam et al. 1983) with minor modifications to minimize RNase activity. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and then with buffer A (10 mM Tris at pH 7.9 at 4°C, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, protease inhibitors, phosphatase inhibitors) and lysed in buffer A with 0.2% IGEPAL CA-630 for 5 min on ice. Nuclei were isolated by centrifugation at 2500g for 5 min and lysed in buffer C (20 mM Tris at pH 7.9 at 4°C, 25% glycerol, 400 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EDTA, 0.4 U/μL murine RNase inhibitor, protease inhibitors, phosphatase inhibitors) for 30 min at 4°C. Lysates were cleared at 20,000g for 30 min. For immunoprecipitation, lysates were diluted to 1 mg/mL in RIP buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.9 at 4°C, 200 mM KCl, 0.05% IGEPAL CA-630, 10 mM EDTA), cleared by centrifugation at 20,000g for 10 min, and incubated with a predetermined, depleting amount of antibody for 3 h at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were recovered as follows. Five microliters of protein G-coupled Dynabeads (Invitrogen) was added per microgram of antibody used and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed in RIP-W buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.9 at 4°C, 200 mM KCl, 0.05% IGEPAL CA-630, 1 mM MgCl2) twice and incubated with 2 U of TURBO DNase (Ambion) in 20 μL of RIP-W buffer for 10 min at room temperature to eliminate potential bridging effects of protein–DNA and RNA–DNA interactions. After two additional washes in RIP-W buffer, RNA was eluted and purified with TRIzol (Invitrogen), and the residual DNA was removed with an additional TURBO DNase treatment.

PAR-CLIP and PAR-CLIP-seq (PAR-CLIP combined with deep sequencing)

PAR-CLIP was performed as described with some modifications (Kaneko et al. 2014). Briefly, U2OS cells were grown under standard conditions and pulsed with 400 μM 4-SU (Sigma) for 16–24 h. After washing the plates with PBS, cells were cross-linked with 400 mJ/cm2 UVA (365 nm) using a Stratalinker UV cross-linker (Stratagene). Whole nuclear lysates (WNLs) were obtained by fractionating cytoplasm and nuclei by a standard method (Dignam et al. 1983), and nuclei were then incubated for 10 min at 37°C in an appropriate volume of CLIP buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 2% lauryldimethylbetaine) supplemented with protease inhibitors, 20 U/mL Turbo DNase (Life technologies), and 200 U/mL murine RNase inhibitor (New England Biolabs). After clearing the lysate by centrifugation, immunoprecipitations were carried out using 200 μg of WNLs, appropriate antibody, and protein G-coupled Dynabeads (Life Technologies) in the same CLIP buffer overnight at 4°C, after which, when required, the extracts were treated with various concentrations of RNase A+T1 cocktail (Ambion) for 5 min at 37°C. Contaminating DNA was removed by treating the beads with Turbo DNase (2 U in 20 μL). Cross-linked RNA was labeled by successive incubation with 5 U of Antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolabs) and 5 U of T4 PNK (New England Biolabs) in the presence of 10 μCi [γ-32P] ATP (PerkinElmer). Labeled material was resolved on 8% Bis-Tris gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and visualized by autoradiography.

For PAR-CLIP-seq experiments, 1 mg of WNLs was employed. 3′-blocked DNA adapter (100 pmol/μL) was ligated to the RNA after dephosphorylation and before 5′-32P end-labeling by incubation of the beads with T4 RNA ligase 1 (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 25°C. Labeled material was resolved on 8% Bis-Tris gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and visualized by autoradiography. The band of interest was excised, and RNA was eluted from the membrane by treatment with 4 mg/mL proteinase K (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C and then with proteinase K in the presence of 3.5 M urea for 30 min at 55°C. After phenol/chloroform extraction, custom-designed 5′ RNA adapters were ligated, the products were size-selected on polyacrylamide gels, and libraries were amplified and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing system.

For the initial PAR-CLIP-seq mapping, we clipped adapter sequences from PAR-CLIP reads and kept those >17 nt. The resulting reads were collapsed to remove duplicate sequences with the FASTX toolkit and then mapped with Bowtie –v2 –m40 –best –strata to the hg19 assembly. Two separate replicates were pooled and then processed with an arbitrary cutoff of five unique reads. The repetitive elements listed by RepeatMasker (as downloaded from the University of California at Santa Cruz Genome Browser Web site on November 1, 2013) were discarded, leaving 17,201 genes. The list of these genes can be found in Supplemental Table S1, and additional sequencing information can be found in Supplemental Table S2. Annotation-based analysis was performed using the ENSEMBL database.

Sequencing data

All sequencing data have been deposited to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus as SuperSeries GSE53554

In vitro binding assays

RNA probes were synthesized from template DNA. Binding assays were carried out in the presence of GST-tagged versions of FL CTCF or its deletion mutants (100 pmol) and Wrap53 cRNA in 100 μL of binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1.5 mM MgSO4). A master mix was prepared to ensure equal loading of RNA for all samples, and the reaction mixture was then incubated for 10 min at 4°C. GST beads were then added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. CTCF–RNA complexes were pulled down using GST beads, washed twice with binding buffer, and divided in half for protein and RNA analysis. Protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by SYPRO Red staining. RNA was purified using TRIzol (Invitrogen), separated by urea 8M-PAGE, and detected by SYBR Gold staining.

Dimer assays

A master mix was prepared with GST-tagged proteins (100 pmol) and 300 μg of NE in 300 μL of binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1.5 mM MgSO4) and then divided into three aliquots: no treatment, RNase A treatment (1 μg; Ambion), and Turbo DNase treatment (5 U). The reaction mixture was then incubated for 1 h at 4°C. GST beads were then added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. CTCF complexes were pulled down using GST beads, washed twice with binding buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, stained with Ponceau Red, and then blotted using antibody against HA.

Cell culture

Inducible U2OS cells expressing human CTCF and CTCFΔ576–614 were generated by transfecting pTRIPZ-shCTCF and the relevant pINTA-N3 constructs (described above) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) followed by selection with 50 μg/mL Zeocin (Invitrogen). Cells were treated with doxycycline for 72 h at a concentration calibrated to allow reduction of the endogenous protein levels and give rise to levels of CTCF and CTCFΔ576–614 similar to that of untreated cells.

Gel filtration chromatography

Recombinant CTCF or RBRs were loaded onto a Superose 6 PC 3.2/30 (GE Life Sciences) 2.4-mL sizing column with or without Wrap53 RNA and fractionated.

EMSA

Recombinant protein was incubated at room temperature with increasing concentrations of competitors prior to adding the RNA probe. RNA probe was then added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in 15 μL of binding buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) at 4°C, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnSO4, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Tween-20, 8 U of RNase inhibitor (New England Biolabs), and 1 μg of yeast transfer RNA (tRNA). Samples were resolved at 4°C by 0.5× TGE and 4% PAGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. L. Vales for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Pedro P. Rocha, Ramya Raviram, and Dr. Jane Skok for discussion and advice. We also thank the Genome Technology Center at New York University for help with sequencing. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH) (GM-64844 and R37-37120) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to D.R., and the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (IN209403 and IN203811) and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, México (CONACyT; 42653-Q and 128464) to F.R.-T. R.S.-M. was supported by a PhD and an international research stay fellowship from CONACyT (213029). E.G.-B was supported by a PhD fellowship from CONACyT and Dirección General de Estudios de Posgrado-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (DGEP; 207989). R.B. was supported by a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation post-doctoral fellowship and the Helen L. and Martin S. Kimmel Center for Stem Cell Biology post-doctoral fellow award. V.N. is supported by an NIH training grant from the Graduate Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology (T32 GM007238). Additional support was provided by the PhD Graduate Program “Doctorado en Ciencias Bioquímicas” to the Instituto de Fisiología Celular and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.236869.113.

References

- Barkess G, West AG 2012. Chromatin insulator elements: establishing barriers to set heterochromatin boundaries. Epigenomics 4: 67–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RS 2005. Zinc finger proteins: getting a grip on RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol 15: 94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Tian Y, Shu W, Bo X, Wang S 2012. Comprehensive identification and annotation of cell type-specific and ubiquitous CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. PLoS ONE 7: e41374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa-Velázquez De IA, Rincón-Arano H, Benítez-Bribiesca L, Recillas-Targa F 2007. Epigenetic regulation of the human retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene promoter by CTCF. Cancer Res 67: 2577–2585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res 11: 1475–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova G, Fagerlie S, Klenova E 1996. An exceptionally conserved transcriptional repressor, CTCF, employs different combinations of zinc fingers to bind diverged promoter sequences of avian and mammalian c-myc oncogenes. Mol Cell Biol 16: 2802–2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landgraf P, Ludwig J, Rice A, Ojo T, Lin C, Holoch D, Lim C, Tuschl T 2008. Identification of microRNAs and other small regulatory RNAs using cDNA library sequencing. Methods 44: 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handoko L, Xu H, Li G, Ngan CY, Chew E, Schnapp M, Lee CWH, Ye C, Ping JLH, Mulawadi F, et al. 2011. CTCF-mediated functional chromatin interactome in pluripotent cells. Nat Genet 43: 630–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda SJB, de Laat W 2013. CTCF: the protein, the binding partners, the binding sites and their chromatin loops. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368: 20120369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huthoff H, Autore F, Gallois-Montbrun S, Fraternali F, Malim MH 2009. RNA-dependent oligomerization of APOBEC3G is required for restriction of HIV-1. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Bonasio R, Saldaña-Meyer R, Yoshida T, Son J, Nishino K, Umezawa A, Reinberg D 2014. Interactions between JARID2 and noncoding RNAs regulate PRC2 recruitment to chromatin. Mol Cell 53: 290–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenova EM, Chernukhin IV, El-Kady A, Lee RE, Pugacheva EM, Loukinov DI, Goodwin GH, Delgado D, Filippova GN, Leon J, et al. 2001. Functional phosphorylation sites in the C-terminal region of the multivalent multifunctional transcriptional factor CTCF. Mol Cell Biol 21: 2221–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanenkov VV, Nicolas RH, Plumb MA, Wright CA, Goodwin GH 1986. Sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins which interact with (G + C)-rich sequences flanking the chicken c-myc gene. Eur J Biochem 159: 181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanenkov VV, Nicolas RH, Adler VV, Paterson H, Klenova EM, Polotskaja AV, Goodwin GH 1990. A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′-flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene 5: 1743–1753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Searles MA, Klug A 2003. Crystal structure of a zinc-finger–RNA complex reveals two modes of molecular recognition. Nature 426: 96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi S, Henriksson S, Corcoran M, Méndez-Vidal C, Wiman KG, Farnebo M 2009. Wrap53, a natural p53 antisense transcript required for p53 induction upon DNA damage. Mol Cell 33: 462–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi S, Henriksson S, Weibrecht I, Smith S, Söderberg O, Strömblad S, Wiman KG, Farnebo M 2010. WRAP53 is essential for Cajal body formation and for targeting the survival of motor neuron complex to Cajal bodies. PLoS Biol 8: e1000521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Pantoja C, Miñán AF, Valdes-Quezada C, Moltó E, Matesanz F, Bogdanović O, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Domínguez O, Taher L, et al. 2011. Genome-wide CTCF distribution in vertebrates defines equivalent sites that aid the identification of disease-associated genes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 708–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mili S, Steitz JA 2004. Evidence for reassociation of RNA-binding proteins after cell lysis: implications for the interpretation of immunoprecipitation analyses. RNA 10: 1692–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi H, Kwon K-RK, Resch W, Vian L, Dose M, Stavreva D, Hakim O, Pruett N, Nelson S, Yamane A, et al. 2013. A genome-wide map of CTCF multivalency redefines the CTCF code. Cell Rep 3: 1678–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R 2001. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet 17: 520–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Corces VG 2009. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell 137: 1194–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins JE, Sauria MEG, Sanyal A, Gerasimova TI, Lajoie BR, Bell JSK, Ong C-T, Hookway TA, Guo C, Sun Y, et al. 2013. Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell 153: 1281–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley KJ, Yario TA, Steitz JA 2012. Association of Argonaute proteins and microRNAs can occur after cell lysis. RNA 18: 1581–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña-Meyer R, Recillas-Targa F 2011. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Epigenetics 6: 1068–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G, Dekker J 2012. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature 489: 109–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles MA, Lu D, Klug A 2000. The role of the central zinc fingers of transcription factor IIIA in binding to 5 S RNA. J Mol Biol 301: 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Reyes E, Recillas-Targa F 2010. Epigenetic regulation of the human p53 gene promoter by the CTCF transcription factor in transformed cell lines. Oncogene 29: 2217–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, del Rosario BC, Szanto A, Ogawa Y, Jeon Y, Lee JT 2013. Jpx RNA activates Xist by Evicting CTCF. Cell 153: 1537–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki HI, Yamagata K, Sugimoto K, Iwamoto T, Kato S, Miyazono K 2009. Modulation of microRNA processing by p53. Nature 460: 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terribilini M, Sander JD, Lee J-H, Zaback P, Jernigan RL, Honavar V, Dobbs D 2007. RNABindR: a server for analyzing and predicting RNA-binding sites in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadez-Graham V, Razin SV, Recillas-Targa F 2004. CTCF-dependent enhancer blockers at the upstream region of the chicken α-globin gene domain. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1354–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Prives C 2009. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell 137: 413–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Wallace J, Felsenfeld G 2011. Specific sites in the C terminus of CTCF interact with the SA2 subunit of the cohesin complex and are required for cohesin-dependent insulation activity. Mol Cell Biol 31: 2174–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Brick K, Evrard Y, Xiao T, Camerini-Otero RD, Felsenfeld G 2010. Mediation of CTCF transcriptional insulation by DEAD-box RNA-binding protein p68 and steroid receptor RNA activator SRA. Genes Dev 24: 2543–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G 2004. CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol Cell 13: 291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatanova J, Caiafa P 2009. CTCF and its protein partners: divide and rule? J Cell Sci 122: 1275–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]