Abstract

Since 1996, several studies characterizing the association between primary immunodeficiencies and susceptibility to infections with environmental and non-pathogenic mycobacteria such as the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus of Calmette Guérin strain) as well as disseminated infections by Salmonella spp. have been conducted. These conditions, grouped in the so-called Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases, include a primary immunodeficiency caused by mutations in 7 autosomal genes (IFNGR1, IFNGR2, IL12B, IL12BR1, STAT1, ISG15, and IRF8) and an X-linked gene (NEMO). This syndrome presents a high degree of allelic heterogeneity and variable penetrance. This review focuses on the analysis of the first reported cases of these diseases, as well as on the molecular findings involved in each of them.

Introduction

Type I cytokines (interferon [IFN]-γ gamma, IL-12, IL-18, IL-23, and IL-17) are very important molecules in the control of infections by intracellular micro-organisms such as Salmonella spp. and mycobacteria. It has been found that defects in the production or signaling of type I cytokines predispose people to suffer infections from weakly pathogenic environmental mycobacteria, or Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus of Calmette Guérin (BCG), when they have been vaccinated. The association between susceptibility to infection and type I cytokine defects was first described by Kamijo, who inoculated IFN-γ receptor-deficient mice with BCG. They noticed the inability of these mice to produce tumoral necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1α, and IL-6 after the infection. In addition, these mice did not develop well-defined granulomas and were unable to kill mycobacteria (Kamijo and others 1993).

Immunological Mechanisms Involved in the Control of Mycobacterial Infections

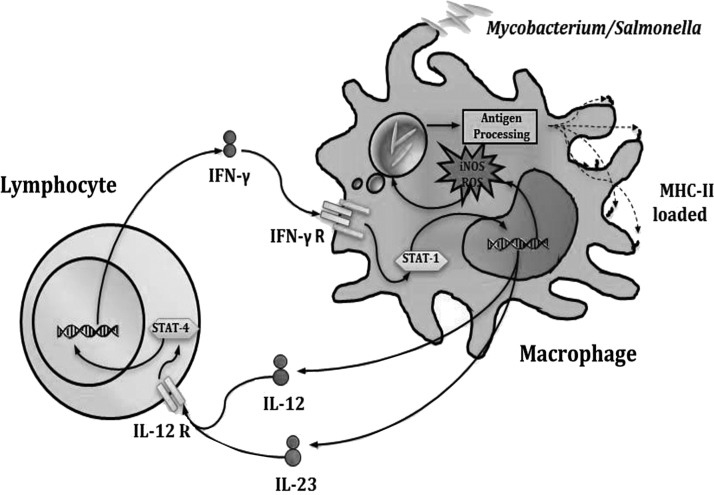

Mycobacteria, similar to other intracellular pathogens, live and multiply within macrophages (Tufariello and others 2003). Once they have been internalized, these intracellular pathogens evade the mechanisms of the phagocytes, thus avoiding their elimination (Golby and others 2007; Djelouadji and others 2008). However, macrophages are able to recognize molecules of these micro-organisms and are thereby activated. Activation occurs when macrophages recognize mycobacterial (Hava and others 2008) Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns through their Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Reiling and others 2001; Sweet and others 2008), triggering cytokine production (Bafica and others 2005; Means and others 1999). Cytokine networks play a crucial role in inducing inflammation and clearing infection (Serbina and Flynn 1999). TFN-α is the first cytokine that is secreted by macrophages, and it plays a key role in granuloma formation and, along with IL-1β, limits bacterial growth (Cooper and Khader 2008). However, IL-12 secretion has a crucial role in host defense against this intracellular pathogen. Its critical role resides in the induction of IFN-γ production by T cells and represents the junction between innate and adaptative immunity (Kaufmann 2002). IL-12 produced after endocytosis of mycobacteria induces activation and differentiation of T cells into T-helper 1 subpopulations and CD8+, which, in turn, secrete IFN-γ (Serbina and Flynn 2001). Thus, the macrophages are activated to eliminate the pathogen, and these interactions lead to further differentiation of the macrophages to the M1 phenotype (Flynn and Chan 2001). Therefore, the communication between innate and adaptive immunity, mediated by IFN-γ and IL-12, plays a very important role in the control of infections by mycobacteria and other intracellular bacteria such as Salmonella (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Immune response against mycobacteria and salmonella. T lymphocytes co-operates through interferon (IFN)-γ secretion, which activates the anti-microbial mechanisms in infected macrophages.

Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Diseases

Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases (MSMDs) is a rare congenital syndrome, which was first reported in 1964 in families with cases of disseminated atypical mycobacteriosis (Engbaek 1964). The condition is defined as a disease with severe clinical features, disseminated or recurrent infection by environmental mycobacteria, and, in some cases, a severe co-infection with Salmonella non-typhi. Salmonella infection in the absence of co-infection with mycobacteria has also been reported (Casanova and Abel 2002).

Since the first cases reported were of patients who presented infection with BCG or environmental mycobacteria, the condition was named MSMD (Picard and others 2006). However, this name is rather misleading, because there are cases with no mycobacterial infection. Instead, other types of intracellular pathogens (eg, Nocardia and Paracoccidioidomyces) have been reported (Zerbe and Holland 2005). Therefore, the name “inborn defects of the IL-12/IFN-γ axis” seems more appropriate (Al-Muhsen and Casanova 2008).

The etiological cause of the infection is a micro-organism; however, mutations in genes encoding any of the molecules involved in the IL-12/IFN-γ axis could be responsible for deficiencies in clearing infections (Reichenbach and others; Zhan and others 2008). To date, several mutations have been described in 7 autosomal genes (IFNGR1, IFNGR2, IL12B, IL12RB1, STAT1, ISG15, and IRF8) and an X-linked gene (NEMO), all of which are involved in MSMD (Bustamante and others 2007). This syndrome shows high allelic heterogeneity, and IL-12 receptor defects are the main cause of this condition (40%), followed by defects in the subunit 1 of IFN-γ receptor (39%). Defects in other molecules (ie, IL-12 p40, STAT1, IFN-γR2, ISG15, IRF8, and NEMO) also contribute to this condition.

IFN-γ

IFN-γ, also known as a type II IFN, is a pleiotropic cytokine that is produced by T and NK cells. Its primary role is to stimulate, within the macrophage, the transcription of class II major histocompatibility genes, costimulatory molecules (eg, CD80), enzymes involved in the production of microbicidic substances (eg, nitric oxide synthase) (Weiss and others 1992), and the p35 subunit of IL-12 (Stark and others 1998). Nairz showed that IFN-γ is not only involved in the induction of the mechanisms described earlier, but also modifies the homeostasis of iron in macrophages to restrict the acquisition of this metal by the bacteria (Janakiraman and Slauch 2000; Nairz and others 2008). This is possible because IFN-γ reduces the expression of transferrin receptor 1 and increases the expression ferroportin 1 (an iron-exporting protein) (Byrd and Horwitz 1989; Oexle and others 2003).

IL-12

IL-12 is a 70-kDa glycoprotein that is composed of 2 subunits of 35 kDa (p35 or IL-12A) and 40 kDa (p40 or IL-12B), which are linked by disulfide bridges. The p35 subunit has a globular domain of 4 alpha helices, while the p40 subunit contains an Ig domain, which is shared with IL-23 (Trinchieri 2003). IL-12 is synthesized by a macrophage that is infected with intracellular bacteria and viruses and/or in response to microbial components such as LPS. Its primary role is the stimulation of the synthesis of IFN-γ by T cells and NK cells, which, in turn, activate macrophages so they can destroy intracellular micro-organisms (Cooper and others 2007).

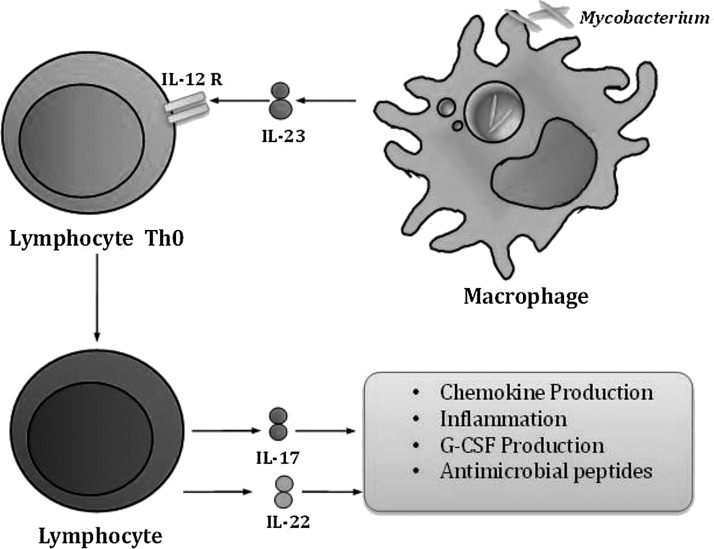

IL-17/IL-23

The activation of dendritic cells (DC) by mycobacteria induces the secretion of IL-12 and IL-23. CD4+ T cells exposed to IL-23 differentiate into TH17 cells in response to mycobacterial infection (Awasthi and Kuchroo 2009) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

IL-17 participation in mycobacterial infection. Mycobacterial infection activates IL-23 secretion by infected macrophages. This cytokine regulates T-lymphocyte differentiation to TH17 population, which co-operates to control infection through IL-17 secretion.

IL-23, in the absence of the IL-12 p70, also induces the secretion of IFN-γ in TH cells, as has been shown in mice deficient of the p35 subunit (MacLennan 2004). However, as demonstrated in p40-deficient mice, the absence of the p40, a subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23, prevents the production of IFN-γ induced by these mechanisms (Khader and Cooper 2008).

γδ T cells are a primary source of IL-17 production in murine models of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. In one of these models, which involved the intratracheal inoculation of BCG, the mRNA for IL-17 was detected only 1 day after infection. In mice deficient of the gene for IL-17, induction of chemokines and the early accumulation of neutrophils is reduced (Curtis and Way 2009). These data indicate the involvement of other soluble mediators that are different from those involved in the IL-12/IFN-γ axis. The molecules and mechanisms involved in the control and elimination of mycobacteria and Salmonella are, thus, becoming clearer.

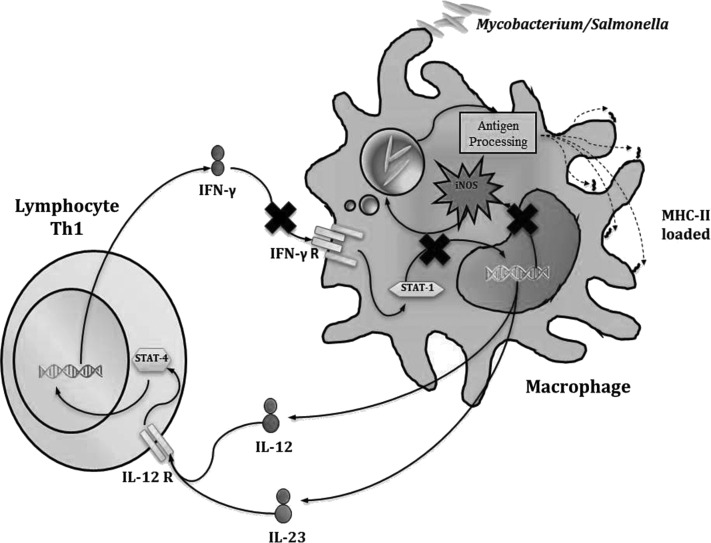

IFN-γR1

The IFN-γ receptor is a heterodimer that is composed of the R1 and R2 subunits. It is mainly expressed in myeloid and lymphoid cells. The homodimer of IFN-γ binds to subunit 1 of the receptor, which, in turn, recruits subunit 2 and starts the signaling via Jak/signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT-1) (Stark and others 1998) (Fig. 3). Jouanguy reported 2 cases of disseminated infections caused by the M. bovis BCG strain. The first was a girl (a daughter of Tunisian parents who were first cousins to each other) who was vaccinated with BCG-Pasteur when she was 1-month old. A month later, mycobacteria were isolated from her lungs and bone marrow. Considering that rare cases of infection with BCG are associated with high rates of consanguinity (30%), familial inheritance (17%), and similar distribution with respect to gender, the existence of a new primary immunodeficiency with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern was proposed (Jouanguy and others 1996). A previous work reported that IFN-Receptor-1-deficient mice were highly susceptible to infection with BCG (Kamijo and others 1993). The formation of granulomas in these mice is defective. With this background, the genes encoding IFN-γ and the IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR1) were analyzed. In addition, mutations in genes that encode TNF-α and TNF-αR1 were studied in children with idiopathic fatal infection by BCG. The results of these analyses showed the existence of a mutation, which resulted in the elimination of nucleotide 131 (C) in the exon 2 of the gene IFNGR1 and the formation of a premature stop codon (Jouanguy and others 1996). The mutation is located in the region that encodes a portion of the extracellular domain of the receptor (N-terminus).

FIG. 3.

Defective response to IFN-γ. Defects in IFN-γR1, IFN-γR2, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) result in unresponsiveness to IFN-γ and an inability to activate the anti-microbial mechanisms in macrophages.

Then, a second group of patients was described (Newport and others 1996). This group consisted of 4 children from Malta who presented a disseminated, atypical mycobacterial infection. Each child was infected with a different species of mycobacteria (M. kumamotonense, M. chelonei, and 2 strains of M. avium). This suggested a defect in their immunity, because these mycobacteria are weakly virulent. In addition, one of the children also acquired Salmonella infection. These studies led to the identification of a different mutation, which consists of a replacement located at position 395 (A for C). This mutation results in a premature stop codon in the sequence of IFNGR1. This generates a receptor that lacks the transmembrane and intracellular domains, and, as a consequence, is absent on the membrane. Both cases result in a complete deficiency of the subunit R1.

Jouanguy described a new mutation in the gene encoding IFN-γR1, which was detected in 2 Portuguese children from consanguineous parents. The older child was vaccinated with BCG when he was 1-month old and rapidly developed a disseminated infection. His younger sister was not inoculated with BCG, but was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of 3. Unlike the 2 previous cases, in which the receptor was absent, the expression of IFN-γR1 was detected on the surface of the cells. A new mutation was found in exon 3 of the gene, which is a replacement of the nucleotide located at position 260 (T/C), which led to a change in the amino acid isoleucine (I) by threonine (T) and altered the structure and function of the receptor. Since the mutation did not affect the expression of the receptor on the membrane, it was determined to be partially deficient in IFN-γR1. The receptor with the I87T mutation could be functional at high concentrations of IFN-γ (Jouanguy and others 1997).

Jouanguy found the deletion of 4 nucleotides from position 818 (818del4). They analyzed 2 unrelated families that had several cases of infections caused by BCG and M. avium over 3 generations of family members. The expression of the receptor by flow cytometry showed higher mean fluorescence intensity when compared with the control. Nevertheless, these cells were unable to respond to the IFN-γ stimulus. In both the families, all individuals were found to be carriers of allele 818del4 located in the region encoding the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor generating a premature stop codon. In heterozygous individuals for the allele, there were a greater proportion of truncated membrane receptors with regard to the functional receptors (Jouanguy and others 1999).

Okada reported the characterization of a mutation in a Japanese 12-year-old girl, who was vaccinated with BCG at 4 months of age. The patient developed regional lymph node inflammation 2 months after administration of the vaccine. The diagnosis was lymphadenitis due to BCG. Molecular analysis showed a dominant mutation in the IFNGR1 gene. The mutation is a deletion of 4 nucleotides from the nucleotide at 774 (774del4), resulting in generation of a premature stop codon. The mutation affects the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor, although it does not affect its presence on the cell surface (Okada and others 2007).

IFN-γR2

This subunit is expressed constitutively in monocytes and DCs, although at levels below subunit 1. Both subunits are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and N-glycosylated in its transition from the ER to the Golgi apparatus (Stark and others 1998).

After the full characterization of IFNGR1 mutations, Holland described a case of infection by mycobacteria that was linked to the alteration of the other subunit of the IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR2) which was responsible for signaling (Fig. 3).

This genetic alteration appeared in a child who was not vaccinated with BCG, and developed a disseminated infection caused by M. fortuitum and M. avium at age 2. The sequence of DNA corresponding to the subunit R2 showed a homozygous elimination of the 278 and 279 nucleotides. This change led to a shift in the reading frame and a premature stop codon (TGA) at nucleotides 282, 283, and 284. The deletion and the premature stop codon are located in exon III, which corresponds to the extracellular portion of the protein (Dorman and Holland 1998). Analysis by flow cytometry showed a normal distribution of the subunit R1, but a total absence of the subunit R2. Two, new mutations in IFNGR2 were described by Vogt. Both led to a complete deficiency, which was detected in 4 unrelated children. Patient 1 (P1) had an infection with M. avium; patient 2 (P2) had an infection with BCG; and patients 3 (P3) and 4 (P4) had infections with M. fortuitum. The mutation found in P1 consisted of an elimination of nucleotides 663–689 (663del27), which led to the loss of amino acids 222–230 in the protein. These changes affected its conformation, and, consequently, there was no binding to subunit 1. Patients 2, 3, and 4 were homozygous for a missense mutation (a change in nucleotides at position 503 C503A generating the codon ACC/AAC). This mutation generates a change in the amino acid threonine by asparagine at position 168 (T168N). This modification in the sequence of the amino acids, which gives rise to a new site of N-glycosylation and prevents the recruitment of subunit 2 by subunit 1, disrupts signaling (Vogt and others 2005). In another family, Döffinger reported a child with disseminated infection by BCG, a change in C for T in position 340, which generated a modification of amino-acid residue 114 (R114C). The phenotype of this defect was not very serious, as the protein was expressed on the membrane and the response to IFN-γ was diminished, but was restored by increasing the concentration of therapeutic IFN-γ (Döffinger and others 2000). Another mutation in this gene was detected by Rosenzweig, which resulted in the elimination of G in position 791 (791delG) and generated a dominant negative effect in heterozygous cells. The case reported by this group consisted of a 15-month-old girl whose parents were consanguineous. She was vaccinated with BCG when she was 3 weeks old and developed a cervical lymphadenitis with the presence of alcohol-acid-resistant bacilli, which later developed into hepatomegaly and osteomyelitis in the right femur. Functional analysis showed a lack of phosphorylation of STAT1 after activation with IFN-γ, and the molecular analysis showed the absence of 2 guanines in positions 791–792. This mutation is located in the region that encodes the transmembrane domain and generates a premature stop codon, which translates into a protein anchored to the membrane but without cytoplasmic domain (Rosenzweig and others 2004). The parents of the patient were heterozygous for the allele 791delG. In vitro, their cells showed a reduction in the phosphorylation of STAT1 after stimulation with IFN-γ. Analysis of the distribution of IFN-γR2 showed a greater proportion of truncated receptors, which suggests a dominant negative effect by this allele.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1

The signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) is critical for the activation of genes induced by IFN-γ (Fig. 3). The homodimer of STAT1 is called Gamma Activator Factor, and this form moves to the nucleus to bind to discrete regulatory sequences called Gamma-Activated Sequence (GAS). The STAT1 gene is composed of 25 exons and encodes a protein with 4 domains: (1) a domain homologous to Scr 2 (SH2), which interacts with subunit 1 of the IFN-γ receptor; (2) the DNA-binding domain (DNA-B); (3) the segment of Tail (TS); and (4) the transactivator domain (Stark and others 1998).

Dupuis investigated alterations in the signaling of the receptor of IFN-γ. They described the case of a 33-year-old French woman, who developed a disseminated infection by BCG in her infancy and continued to suffer from recurrent infections of the viral type. IFN-mediated signaling and its receptor were evaluated by examining activation levels of IFN-γ-dependent genes. A heterozygous substitution (T/C) in nucleotide 2116, which resulted in a replacement of serine by leucine at residue 706 (L706S), was identified in the sequence of STAT1 (Dupuis and others 2001). The defect in STAT1 was the absence of tyrosine phosphorylation at residue 701. Therefore, the homodimer could not be formed, because of which it could not relocate to the nucleolus to perform its function.

Chapgier found 2 mutations in STAT1, which were characterized in 2 non-related children. The first consisted of a nucleotide substitution (G/C) at position 958 of exon 11. This mutation caused a change in glutamic acid by glutamine at position 320 (E320Q). Glutamic acid forms an ionic bond with the residues histidine and lysine, which forms a loop that enables STAT1 to interact with the grooves of the DNA. The second child showed a heterozygous substitution at position 1389 (G by T) in exon 17. The result was a change of glutamine by histidine at position 463 (Q463H) (Chapgier and others 2006). Glutamine binds with the nitrogenous bases, while histidine binds with the phosphates on the outside of the molecule where it avoids the interaction with nitrogenous bases.

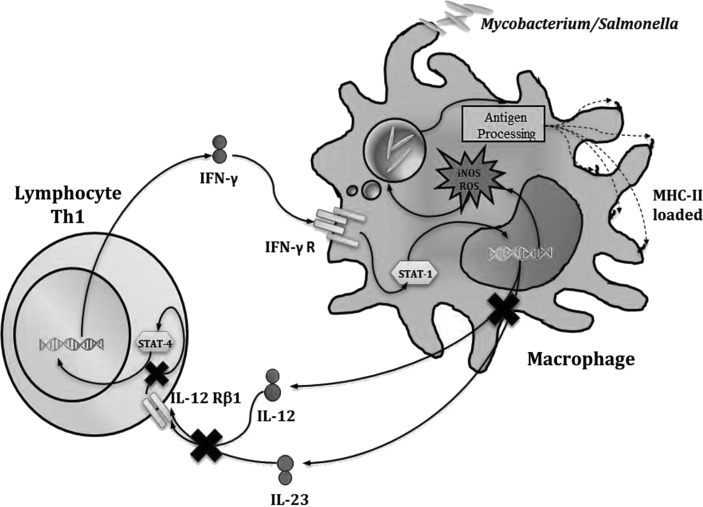

IL12-p40

As previously mentioned, the mature and functional form of IL-12 is a heterodimer composed of the subunits p40 (which is shared with IL-23) and p35. However, it is proposed that the p40 subunit can form a homodimer with activity in the control of intracellular pathogens. Twenty patients have been identified in the last 10 years with 5 different mutations, of which only 4 have been published (Trinchieri 2003). All mutations are recessive and generate a complete deficiency in IL-12 p40 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Defective response to IL-12. Defects in IL-12p40 and IL-12Rβ1 impair IFN-γ production by T lymphocytes.

The first case of a defect in this molecule was of a girl who was immunized at birth with BCG. Three months later, the patient developed tuberculosis with well-defined clinical features. At 3.5 months of age, the patient also developed severe gastroenteritis with bloody diarrhea caused by Salmonella enteritidis. Through molecular analysis of the genes encoding subunits p40 and p35 of lL-12, a deletion in the gene for the p40 subunit of 373 nucleotides between positions 482 and 854 was found (482+82_856-854del). The gene for the p40 subunit consists of 7 exons. Thus, the elimination of the 4.6 kb includes exons 4 and 5. This deletion results in a protein of 184 amino acids instead of the 307-amino-acid native protein (Altare and others 1998).

The second mutation has been identified in 3 patients from Tunisia, who had a deletion of 8 nucleotides from nucleotide 278 (278del8). This mutation occurs in exon 3 and results in a premature stop codon. No detectable levels of IL-12 p40 and IL-12 p70 were found in these patients (Elloumi-Zghal and others 2002). The third mutation was detected in an Arabian family, and it consists of addition of an A at position 315 (315_316insA). This mutation results in the loss of 223 of the original 328 amino acids and in the addition of 9 new C-terminal amino acids. The encoded protein lacks all the amino acids that are essential for p40 dimerization with p35 (Picard and others 2002). In an Iranian patient, a deletion of 2 nucleotides at position 526 (526del2) was detected. This deletion leads to a premature stop codon and no detectable protein (Mansouri and others 2005). However, it has been found that the haplotypes 482+82_856-854del and 315insA are highly conserved in that population. Population-based studies have tracked these and have shown that the first haplotype originated in the Indian subcontinent 700 years ago, while the second haplotype originated 1,100 years ago in the Arabic peninsula (Picard and others 2002).

Another interesting relationship relates to disseminated infections by Salmonella and defects in IL-12 p40 and its receptor (De Jong and others 1998). In more than half of the reported cases, there was co-infection of mycobacteria and Salmonella, suggesting a significant participation of IL-12 in the control of these 2 bacteria (MacLennan and others 2004). In contrast, the relationship between the susceptibility to co-infection of mycobacteria and Salmonella with defects in the signaling pathway of IFN-γ was ∼6% of the reported cases (Filipe-Santos and others 2006).

IL-12Rβ1

The IL-12 receptor is composed of 2 subunits: IL-12Rβ1 and IL-12Rβ2. It is expressed by T and NK cells. Subunit 1 is expressed constitutively, while subunit 2 is expressed only after the activation of the cells. The expression of both subunits is crucial for achieving a high-affinity interaction with the cytokine (Trinchieri 2003). The receptor signals through the Janus protein kinase 2 (Jak2) and Tyk2, which recruit and phosphorylate monomers of the STAT4 protein (Fig. 4). The phosphorylated monomers form a homodimer, which moves to the nucleus and acts as a transcription activator. The IL12RB1 gene consists of 17 exons, which encode for 662 amino acids with a molecular weight of 100 kDa.

Altare described the deficiency in the IL-12 receptor and its participation in MSDM. Four unrelated patients who had disseminated BCG infection were included in this study; 2 of them presented with symptoms. In addition, infections were caused by Salmonella non-typhi. In this work, they investigated mutations in the subunits of the receptor for IL-12, finding a replacement (A/T) in position 913 of the gene that encodes the IL-12Rβ1 subunit (Altare and others 1998). As in previous cases, the patients were homozygous for this mutation, which was inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. However, the patients responded adequately to treatment with IFN-γ.

To date, defects in this molecule are the main etiological cause of MSMD. All reported mutations cause a complete loss of function of the receptor (Fieschi and others 2004).

Susceptibility generated by this genetic condition had only been reported in infections by atypical or weakly virulent mycobacteria and Salmonella (Sanal and others 2006). However, in 2005, Moraes-Vasconcelos reported a 24-year-old man of Portuguese ancestry, who was vaccinated at birth with BCG and was transferred to the hospital at 7 months, owing to cervical adenopathy caused by M. bovis BCG. At the age of 6, he suffered from a disseminated infection by Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium, which caused multiple lymphadenitis, arthritis in the right side of the hip, and osteomyelitis in the right femur. At age 20, he presented with a persistent fever, abdominal pain, disseminated lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. An abdominal lymph node biopsy revealed an acute form of infection by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Moraes-Vasconcelos and others 2005). A missense mutation was found in the gene for IL-12Rβ1, in which the phenylalanine at residue 77 is changed to leucine. The pattern of inheritance is recessive, and there is no presence of the receptor on the surface of the cell.

Similar to patients with defects in the IL-12 p40 subunit, more than half of the patients diagnosed with defects in the IL12Rβ1 subunit presented with Salmonella infections. Despite the severity of the defects at this level, the prognosis is encouraging because only 17% of patients have died. The surviving patients have been under continuous treatment with antibiotics and an IFN-γ recombinant. With this regime, their conditions have improved and they have survived into adulthood (Filipe-Santos and others 2006).

The penetrance of the defects in IL12RB1 is around 40% (Fieschi and others 2003). A 2004 study carried out by Remus included 101 families, with at least 1 case of active pulmonary tuberculosis, and 78 healthy individuals showed the presence of 19 point mutations (Remus and others 2004). Nine of the mutations had been previously described and the other 10 were unknown. Within these mutations, 13 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were detected. The study included one population, which was divided into 2 ethnic groups: Arabs and Moroccans. These SNPs may be used as markers for population studies of the association of these polymorphisms and susceptibility pulmonary tuberculosis.

In a more recent study, Yancoski tracked the haplotype 1623_1624delinsTT in the gene IL12RB1. This haplotype was detected in 5 Argentinian families of European descent. The analysis estimated that this genetic variation could be traced back 475 years (Yancoski and others 2009). This time corresponds to the beginning of the colonization of the Americas by the Europeans. This allows for the speculation that some genetic variants in this gene have both an ethnic and ancestral component.

In 2010, Pedraza reported a Mexican patient with a mutation in IL12RB1, but with a spectrum of infections other than those already reported. The patient presented with BCGitis subsequent to the administration of the BCG vaccine, continuing with disseminated salmonellosis (Pedraza and others 2010). Both infections gave way after treatment with antibiotics. Subsequently, the patient developed meningitis caused by Candida albicans, which was resolved with appropriate treatment. At the end of her illness, she presented sepsis caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. The mutation found in this patient generated a premature stop codon, and, therefore, a truncated IL12BR1 was unable to reach the cell surface (Pedraza and others 2010). The interesting feature here is the infection by K. pneumoniae, which was again reported in 2 cases with a defect in IL-12Rβ1 by Casanova and others and M. Levin (personal communication cited by Pedraza S.). However, it has been reported that the subunit β1 is essential for the control of infection by K. pneumoniae and, because it is the subunit shared by the IL-23 receptor, is responsible for the maintenance of the population of TH17 cells. This population is a major producer of IL-17 and IL-22, which have been reported as key cytokines in the control of disseminated infections by K. penumoniae in a murine model. This provides new evidence of the convergence of both TH1/TH17 and their importance in the control of different infections (Curtis and Way 2009).

NEMO

NEMO encodes the essential modulator of nuclear factor κB (NFκB). Consisting of 10 exons, this gene is located on chromosome X. Several families of receptors signaling through NFκB and NEMO activation are involved in the cellular processes of differentiation, activation, proliferation, and death. NEMO has the following structure: motifs of coiled coil (CC1 and CC2), a leucine zipper domain (LZ), and a zinc finger domain. Amorphic mutations in NEMO (mutations that prevent the functionality of the allele) turn out to be lethal in utero in male fetuses. Hypomorphic mutations (in these, it reduces, but does not eliminate, the expression of the gene or the activity of the gene product) are associated with X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency (Filipe-Santos and others 2006).

These pathologies are the least frequent causes of MSMD. Infections by mycobacteria in X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency patients have been widely documented. In the cells of patients with defects in NEMO, there is a poor production of IFN-γ and IL-12 after stimulation with PHA or agonistic anti-CD3 antibodies. E315 and R319 amino acids are structurally similar and form highly conserved salt bridges within the domain of the LZ of NEMO, suggesting that mutations in these amino acids can disrupt the local plasticity of the structure of LZ interfering in NFκB signaling.

Mycobacterial infections have been identified in 6 of the characterized patients, while the remaining patient presented with a disseminated infection by Haemophilus influenzae b. This infection suggests that mutations in NEMO are not exclusively associated with susceptibility to mycobacteria. The absence of other infections in these patients, however, indicates the correct activation of NFκB in other pathways (TLR, IL-1β). The most common infection is M. avium (although 1 of the patients had a co-infection with M. tuberculosis), implying NEMO in tuberculosis. This observation is interesting due to the high incidence of tuberculosis in men compared with women (Filipe-Santos and others 2006).

Orange reported a 17-year-old patient without ectodermal abnormalities but with H. influenzae and M. bovis infections. He harbored a de novo G-to-A substitution at position 1056 of the NEMO gene, 1 nucleotide before the exon 9-splice site generating an mRNA without an exon 9 sequence. This variant generates an aberrant protein, which lacks the LZ but does not affect the total level of the NEMO protein (Orange and others 2004). The absence of ectodermal dysplasia in this patient suggests that the function of the LZ domain in the normal development of the ectoderm is dispensable but its participation in immunologically relevant signals is significant.

Later, Sebban-Benin characterized a 12-year-old girl who developed incontinentia pigmenti. She carried a heterozygous X-linked substitution at position 967 (G967C) that generated an amino-acid change at position 323 (A323P). This site is critical for TRAF6-dependent polyubiquitination of NEMO and subsequent NFκB activation (Sebban-Benin and others 2007).

IFN regulatory factor 8

IFN regulatory factor 8 (IRF8), otherwise known as IFN consensus sequence-binding protein, is a member of the IRF family of transcription factors that is induced by IFNs in a variety of cell types. IRF8 is induced by IFN-γ in macrophages and T cells, with induction mediated by a GAS element in the IRF8 promoter. The family is characterized by a DNA-binding domain in the N-terminal half of the proteins and an IRF association domain in the C-terminus that is responsible for heterodimerization with other transcription factors (Wang and Morse 2009).

A larger number of studies have demonstrated that IRF8 plays critical roles in the differentiation of myeloid cells, promoting monocyte compared with granulocyte differentiation. It is also a crucial controller of many aspects of DC differentiation and function, thereby playing an essential role in the establishment of innate immunity. However, in the last several years, it has been shown that IRF8 is expressed at relatively low levels in peripheral follicular B cells and at high levels in germinal center (GC) B cells of both mice and humans. In GC, IRF8 modulates the expression of BCL6 and AID (Wang and Morse 2009).

Acting in heterodimeric complexes with other members of the IRF family, IRF8 also controls the transcriptional response of mature myeloid cells to IFNs and TLR agonists. In this response, IRF8 binds to and transactivates the promoters of IL12B and NOS2, which encode for inducible nitric oxide synthase. Mice with mutant Irf8 are susceptible to infection with macrophagic pathogens and are hypersusceptible to M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis infections.

Hambleton and coworkers reported the first patients with MSMD related to mutations in IRF8. They found 2 alleles in 3 unrelated kindred. The first patient was a 10-week-old infant with no monocytes and DCs. This patient harbored a homozygous missense variant that was predicted to cause the substitution of glutamic acid for lysine at position 108 (K108E). Both parents were heterozygous for K108E, and an unaffected sibling lacked the variant allele (Hambleton and others 2011). Most importantly, amino acid position 108 is within the DNA-binding domain of IRF8. The lysine residue is invariant in the IRF8 orthologs and is highly conserved among human IRF family members. Moreover, K108 is localized in a short β strand that runs parallel to the major DNA-binding α helix, suggesting that it makes a critical hydrogen bond with the DNA sugar backbone which facilitates IRF8 docking onto DNA. Therefore, the replacement of a positively charged amino acid (lysine) by one that is negatively charged (glutamic acid) at position 108 would prevent the formation of a hydrogen bond and cause local repulsion of the supporting IRF8 β strand away from DNA, thus allowing a water molecule to fill the space.

Another 2 unrelated kindred with Italian ancestry, but living in Brazil and Chile, were each found to carry the same de novo heterozygous mutation that was predicted to cause the threonine-to-alanine substitution at position 80 (T80A) of IRF8. Amino acid position 80 of IRF8 is within the DNA-binding domain. The threonine residue is strictly conserved across IRF8 orthologs and human paralogous genes. T80 is in the DNA-binding α helix of IRF8 that fits into the major groove, with its side chain directed toward the DNA bases. T80A alters the hydrophobic interface between the protein and DNA and possibly modulates the DNA-binding specificity of IRF8. Alanine has a smaller side chain than threonine, which may allow the entry of a water molecule at the DNA-IRF8 interface (Hambleton and others 2011).

ISG15

Ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 is a 15-kDa protein that is synthesized in many cell types and secreted from human monocytes and lymphocytes. Similar to ubiquitin, ISG15 is conjugated to numerous cellular proteins via isopeptide bonds. This ISG15 conjugation (ISGylation) utilizes the ubiquitin enzyme E1 ligase (UBE1L) as the E1 enzyme, UbcH8 as the E2 enzyme, and some ubiquitin E3 ligases (eg, EFP and HERC5) as the E3 enzyme. ISG15 is strongly induced by type I IFNs. Viral infection also strongly induces ISG15 and a number of proteins that are involved in antiviral signaling pathways, including RIG-I, MDA-5, Mx1, PKR, STAT1, and JAK1, which have been identified as target proteins for ISGylation. However, human monocytes and lymphocytes have been shown to secrete the mature form of ISG15. ISG15 secretion has been detected after treatment with IFN-α/β and free ISG15 has been shown to induce the secretion of IFN-γ by NK cells and T cells (Jeon and others 2010).

Recently, Bogunovic reported the first defect in ISG15 related to MSMD. They described 2 unrelated kindred, which presented with 2 homozygous mutations. The first mutation was found in a 15-year-old girl from Turkey and consisted of a nonsense mutation in exon 2 at position c.379G>T. This generated a premature stop codon and a truncated protein (E127×). The second mutation was characterized in a 12-year-old boy from Iran and his 15-year-old brother. This consisted of a frameshift insertion in ISG15 (c.336_337insG), and this mutation did not result in a premature stop codon (L114fs). Instead, it led to the production of a protein consisting of a 187-amino-acid length rather than 165. Both alleles led to a loss of expression and a loss of function (Bogunovic and others 2012). Three patients did not present with susceptibility to viral infections, similar to the reports of the trait in ISG15−/− mice. Nevertheless, these patients showed impairment in IFN-γ production in response to BCG and IL-12, displaying a similar phenotype of patients with inborn IL-12 p40 and IL-12Rβ1 deficiency. A lack of IFN-γ production was restored in addition to human recombinant ISG15. This showed the importance of IFN-γ secretion dependence on ISG15 solubility, which was not dependent on ISGylation. They demonstrated that NK cells were the most responsive and, therefore, the main type of cells affected in these patients.

Concluding Remarks

MSMD is defined as a genetic predisposition to infection by weakly pathogenic BCG and some environmental nontuberculoid mycobacteria. Its clinical features range from local recurrent to disseminated forms of the nonpathogenic mycobacterial infections, and these clinical variations are influenced by type of molecular defect observed in the IFN-γ/IL-12 axis. In some cases, however, the syndrome segregates as autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or X-linked. Mutations in 7 genes involved in this disease have been described: subunits 1 and 2 of IFN-γ receptor (IFNGR1, IFNGR2); STAT1; subunit p40 of IL-12 (IL12B); the receptor β1 of IL-12 (IL12RB1); ubiquitin-like protein ISG15 (ISG15); and IRF8; all these were involved in the circuit of IL-12/IFN-γ (Table 1). Recently, mutations in the modulator of NFκB (NEMO), which is an X-linked defect, have been described. The mutations affect the NEMO LZ domain, which precludes the activity of NFκB and, therefore, prevents transcription of IL-12 and other genes activated by the IFN-γ. However, it does not affect ectodermal development.

Table 1.

Current List of Defects Found in the 8 Genes Involved in the Etiology of MSMD

| Gene | Inheritance | Defect |

|---|---|---|

| IFN-γR1 | AR | Complete |

| AR | Complete | |

| AD | Partial | |

| AR | Partial | |

| IFN-γR2 | AR | Complete |

| AR | Complete | |

| AR | Partial | |

| Stat-1 | AD | Partial |

| AD | Partial | |

| IL-12B | AR | Complete |

| IL12Rβ1 | AR | Complete |

| AR | Complete | |

| AR | Partial | |

| NEMO | X-L | Partial |

| ISG15 | AR | Complete |

| IRF8 | AR | Complete |

| AD | Complete |

AR, autosomal recessive inheritance pattern; AD, autosomal dominant inheritance pattern; X-L, X-linked inheritance pattern; MSMD, Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease.

The genetic and cellular analysis of this disease has allowed a broader vision about the mechanisms and the clinical, genetic, and immunological implications involved in the control of tuberculosis. On the other hand, the discovery of these defects has provided a more effective treatment for patients and, therefore, a better prognosis based on the type of genetic defect that they suffer from, as it has been demonstrated by the application of recombinant IFN-γ in those patients with defects in IL-12 p40 or its receptor. In those diseases presenting a complete defect, genetic counseling is presented to the patients and their families, thanks to a better understanding of the magnitude of the problem and the etiology of the disease.

As has been mentioned, polymorphisms in IL12RB1 and NEMO can influence susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. Studies demonstrating this association have found variations in the LZ domain of NEMO, which do not generate anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia but may participate in susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis. However, the mechanisms correlating to the IL-12/IFN-γ axis with variants of NEMO are not yet clear.

Finally, the description of this syndrome has allowed a better diagnosis for patients whose prognosis, some years ago, was not encouraging. These studies have also allowed the implementation of new treatments to cure, or at least to alleviate, the disease in the most satisfactory manner. Therefore, clinicians have extended the panorama of possibilities to understand and treat persistent or rare infections by mycobacteria and Salmonella non-typhi.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología del Distrito Federal (ICyTDF) (Grant PICSA12-157) and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) (Grant 153733). NRA is supported by doctoral scholarship 456878 from CONACyT. The authors acknowledge José Luis Maravillas-Montero for his help in elaborating the figures and Héctor Romero-Ramírez for technical assistance rendered.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Al-Muhsen SA, Casanova JL. 2008. The genetic heterogeneity of mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122(6):1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altare F, Durandy A, Lammas D, Emile JF, Lamhamedi S, Le Deist F, Drysdale P, Jouanguy E, Döffinger R, Bernaudin F, Jeppsson O, Gollob JA, Meinl E, Segal AW, Fischer A, Kumararatne D, Casanova JL. 1998. Impairment of mycobacterial immunity in human interleukin-12 receptor deficiency. Science 280:1432–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altare F, Lammas D, Revy P, Jouanguy E, Döffinger R, Lamhamedi S, Drysdale P, Scheel-Toellner D, Girdlestone J, Darbyshire P, Wadhwa M, Dockrell F, Salmon M, Fischer A, Durandy A, Casanova JL, Kumararatne DS. 1998. Inherited interleukin 12 deficiency in a child with bacilli Calmette-Guérin and Salmonella enteritidis disseminated infection. J Clin Invest 102:2035–2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. 2009. TH17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int Immunol 21(5):489–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafica A, Scanga CA, Feng CG, Leifer C, Chever A, Sher A. 2005. TLR9 regulates Th1 responses and cooperates with TLR2 in mediating optimal resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med 202:1715–1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogunovic D, Byunn M, Durfee LA, Abhyankar A, Sanal O, Mansouri D, Salem S, Radovanovic I, Grant AV, Adimi P, Mansouri N, Okada S, Bryant VL, Kong XF, Kreins A, Moncada Velez M, Boisson B, Khalizadeh S, Ozcelik U, Darazam IA, Schoggins JW, Rice CM, Al-Muhsen S, Behr M, Vogt G, Puel A, Bustamante J, Gros P, Huibregtse JM, Abel L, Boisson-Dupuis S, Casanova JL. 2012. Mycobacterial disease and impaired IFN-γ immunity in humans with inherited ISG15 deficiency. Science 10(1126):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante J, Picard C, Fieschi C, Filipe-Santos O, Feinberg J, Perrone C, Chapgier A, de Beaucoudrey L, Vogt G, Sanlaville D, Lemainque A, Emile JF, Abel L, Casanova JL. 2007. A novel X-linked recessive form of Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease. J Med Genet 44:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd TF, Horwitz MA. 1989. Interferon gamma-activated human monocytes downregulate transferrin receptors and inhibit the intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila by limiting the availability of iron. J Clin Invest 83:1457–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova JL, Abel L. 2002. Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Ann Rev Immunol 20:581–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapgier A, Boisson-Dupuis S, Jouanguy E, Vogt G, Feinberg J, Pochnicka-Chalufour A, Casrouge A, Yang Kun , Soudais C, Fieschi C, Filipe-Santos O, Bustamante J, Picard C, de Beaucoudrey L, Emile JF, Arkright PD, Schreiber RD, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Rösen-Wolff A, Magdorf K, Roesler J, Casanova JL. 2006. Novel STAT1 alleles in otherwise healthy patients with mycobacterial disease. PLoS Genet 2:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AM, Khader SA. 2008. The role of cytokines in the initiation, expansion, and control of cellular immunity to tuberculosis. Immun Rev 226:191–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AM, Solache A, Khader SA. 2007. Interleukin-12 and tuberculosis: an old story revisited. Curr Opin Immunol 19(4):441–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MM, Way SS. 2009. Interleukin-17 in host defense against bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal pathogens. Immunology 126:177–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong R, Altare F, Haagen IA, Elferink DG, Boer T, van Breda Vriesman PJ, Kabel PJ, Draaisma JM, van Dissel JT, Kroon FP, Casanova JL, Ottenhoff TH. 1998. Severe mycobacterial and Salmonella infections in interleukin-12 receptor-deficient patients. Science 280:1435–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djelouadji Z, Raoult D, Daffe M, Drancourt M. 2008. A single-step sequencing method for the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex species. Plos Neg Trop Dis 2(6):e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman SE, Holland SM. 1998. Mutation in the signal-transducing chain of the interferon gamma receptor and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. J Clin Invest 101:2364–2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis S, Dargemont C, Fieschi C, Thomassin N, Rosenzweig S, Harris J, Hollan SM, Schereiber RD, Casanova JL. 2001. Impairment of mycobacterial but not viral immunity by a germline human STAT1 mutation. Science 293:300–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döffinger R, Jouanguy E, Dupuis S, Fondanéche MC, Stephan JL, Emile JF, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Altare F, Pallier A, Barcenas-Morales G, Meinl E, Krause C, Pestka S, Schreiber RD, Novelli F, Casanova JL. 2000. Partial interferon gamma receptor signalling chain deficiency in a patient with bacille Calmette-Guérin and Mycobacterium abscessus infection. J Infect Dis 181:379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elloumi-Zghal H, Barbouche MR, Chemli J, Bejaoui M, Harbi A, Snoussi N, Abdelhak S, Dellagi K. 2002. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity of inherited autosomal recessive susceptibility to disseminated Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin infection. J Infect Dis 185:1468–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engbaek HC. 1964. Three cases in the same family of fatal infection M. avium. Acta Tuberc Pneumol Scand 45:105–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieschi C, Bosticardo M, de Beaucodrey L, Boisson-Dupuis S, Feinberg J, Santos OP, Bustamante J, Levy J, Candotti F, Casanova JL. 2004. A novel form of complete IL-12/IL-23 receptor β1 deficiency with cell surface-expressed nonfunctional receptors. Immumobiol 104(7):2095–2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieschi C, Dupuis S, Catherinot E, Feinberg J, Bustamante J, Breiman A, Altare F, Baretto R, Le Deist F, Kayal S, Koch H, Richter D, Brezina M, Aksu G, Wood P, Al-Jumaah S, Raspall M, Da Silva Duarte AJ, Tuerlinckx D, Virelizier JL, Fischer A, Enright A, Bernhöft J, Cleary AM, Vermylen C, Rodríguez-Gallego C, Davies G, Büttlers-Sawatzki R, Siegrist CA, Ehlayel MS, Novelli V, Haas WH, Levy J, Freihorst J, Al-Hajjar S, Nadal D, De Moraes-Vasconcelos D, Jeppsson O, Kutukculer N, Frecerova K, Caragol I, Lammas D, Kumararatne DS, Abel L, Casanova JL. 2003. Low penetrance, broad resistance, and favorable outcome of interleukin 12 receptor β1 deficiency: medical and immunological implications. J Exp Med 197(4):527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipe-Santos O, Bustamante J, Chapgier A, Vogt G, de Beaucoudrey L, Feinberg J, Jouanguy E, Boisson-Dupuis S, Fieschi C, Picard C, Casanova JL. 2006. Inborn errors of IL-12/23 and IFN-γ mediated immunity: molecular, cellular, and clinical features. Semin Immunol 18:347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL, Chan J. 2001. Tuberculosis: latency and reactivation. Infect Immun 69:4195–4201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golby P, Hatch AK, Bacon J, Cooney R, Riley P, Allnut J, Hinds J, Nunez J, Marsh PD, Hewinson RG, Gordon SV. 2007. Comparative transcriptomics reveals key gene expression differences between the human and bovine pathogens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Microbiology 153:3323–3336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton S, Salem S, Bustamante J, Bigley V, Boisson-Dupuis S, Azevedo J, Fortin A, Haniffa M, Ceron-Gutierrez L, Bacon CM, Menon G, Trouillet C, McDonald D, Carey P, Ginhoux F, Alsina L, Zumwalt TJ, Kong XF, Kumararatne D, Butler K, Bubeau M, Feinberg J, Al-Muhsen S, Cant A, Abel L, Chaussabel D, Doffinger R, Talenski E, Grumach A, Duarte A, Abarca K, Moraes-Vasconcelos D, Burk D, Berghuis A, Geissmann F, Collin M, Casanova JL, Gros P. 2011. IRF8 mutations and human dendritic-cell immunodeciency. N Engl Med 365:127–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hava LD, van der Wel N, Cohen N, Dascher CC, Houben D, León L, Agarwal S, Sugita M, van Zon M, Kent SC, Shams H, Peters PJ, Brenner MB. 2008. Evasion of peptide, but not lipid antigen presentation, through pathogen-induced dendritic cell maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:11281–11286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janakiraman A, Slauch JM. 2000. The putative iron transport system SitABCD encoded on SPI1 is required for full virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 35:1146–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon YJ, Yoo HM, Chung CH. 2010. ISG15 and immune disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802(5):485–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouanguy E, Altare F, Lamhamedi S, Revy P, Emile JF, Newport M, Levin M, Blanche S, Seboun E, Fischer A, Casanova JL. 1996. Interferon-gamma-receptor deficiency in an infant with fatal bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. N Engl J Med 335:1956–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Altare F, Fondanéche MC, Tuerlincx D, Blanche S, Emile JF, Gaillard JL, Schreiber R, Levin M, Fischer A, Hivroz C, Casanova JL. 1997. Partial interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency in a child with tuberculoid bacillus Calmette-Guerin infection and a sibling with clinical tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 100:2658–2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Lammas D, Dorman SE, Fondanèche MC, Dupuis S, Döffinger R, Altare F, Girdlestone J, Emile JF, Ducoulombier H, Edgar D, Clarke J, Oxelius VA, Brai M, Novelli V, Heyne K, Fischer A, Holland SM, Kumararatne DS, Schreiber RD, Casanova JL. 1999. A human IFNGR1 small deletion hotspot associated with dominant susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. Nat Genet 21:370–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo R, Le J, Shapiro D, Havell EA, Huang S, Aquet M, Bosland M, Vilcek J. 1993. Mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor have profoundly altered responsesnto infection with bacillus Calmette-Guérin and subsequent changes with lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med 178:14.35–14.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann SHE. 2002. Protection against tuberculosis: cytokines, T cells, and macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 61:54–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khader SA, Cooper AM. 2008. IL-23 and IL-17 in tuberculosis. Cytokine 41:79–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan C, Fieschi C, Lammas DA, Picard C, Dorman SE, Sanal O, Mac Lennan JM, Holland SM, Ottenhoff TH, Casanova JL, Kumararatne DS. 2004. Interleukin 12 and interleukin 23 are key cytokines for immunity against Salmonella in humans. J Infect Dis 190:1755–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri D, Adimi P, Mirsaeidi M, Mansouri N, Khalilzadeh S, Masjedi MR, Adimi P, Tabarsi A, Naderi M, Filipe-Santos O, Vogt G, de Beaucoudrey L, Bustamante J, Chapgier A, Feinberg J, Velayati AA, Casanova JL. 2005. Inherited disorders of the IL-12-IFN-gamma axis in patients with disseminated BCG infection. Eur J Pediatr 164:753–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means TK, Wang S, Lien E, Yoshimura A, Golenbock DT, Fenton MJ. 1999. Human toll-like receptors mediate cellular activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 99:3920–3927 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes-Vasconcelos D, Grumach AS, Yamaguti A, Andrade ME, Fieschi C, de Beaucoudrey L, Casanova JL, Duarte AJ. 2005. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis disseminated disease in a patient with inherited deficiency in the beta1 subunit of the interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23 receptor. Clin Infect Dis 41:e31–e37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz M, Fritsche G, Brunner P, Talasz H, Hantke K, Weiss G. 2008. Interferon-γ limits the availability of iron for intramacrophage Salmonella typhimurium. Eur J Immunol 38:1923–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport MJ, Huxley CM, Huston S, Hawrylowicz CM, Oostra BA, Williamson R, Levin M. 1996. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Engl J Med 335:1941–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oexle H, Kaser A, Most J, Bellmann-Weiler R, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Weiss G. 2003. Pathways for the regulation of interferon-gamma-inducible genes by iron in human monocytic cells. J Leukoc Biol 74:287–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Ishikawa N, Shirao K, Kawaguchi H, Tsumura M, Ohno Y, Yasunanga S, Ohtsubo M, Takihara Y, Kobayashi M. 2007. The novel IFNGR1 mutation 774del4 produces a truncated for of interferon-γ receptor1 and has a dominant negative effect on interferon-γ signal transduction. J Med Genet 44:485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange JS, Levy O, Brodeur SR, Krzewski K, Roy RM, Niemela JE, Fleisher TA, Bonilla FA, Geha RS. 2004. Human nuclear factor kappa B essential modulator mutation canresult in immunodeficiency without ectodermal dysplasia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114:650–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza S, Lezana JL, Samarina A, Aldana R, Herrera MT, Boisson-Dupuis S, Bustamante J, Pages P, Casanova JL, Picard C. 2010. Clinical disease caused by Klebsiella in 2 unrelated patients with interleukin 12 receptor β1 deficiency. Pediatrics 126:e971–e976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza-Sanchez S, Herrera-Barrios MT, Aldana-Vergara R, Neumann-Ordoñez M, Gonzalez-Hernandez Y, Sada-Díaz E, de Beaucoudrey L, Casanova JL, Torres-Rojas M. 2010. Bacille Calmette-Guérin infection and disease with fatal outcome associated with a point mutation in the interleukin-12/interleukin-23 receptor beta-1 chain in two Mexican families. Int J Infect Dis 14:256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C, Casanova J, Abel L. 2006. Mendelian traits that confer predisposition or resistance to specific infections in humans. Curr Opin Immunol 18:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C, Fieschi C, Altare F, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hajjar S, Feinberg J, Dupuis S, Soudais C, Al-Mohsen IZ, Génin E, Lammas D, Kumararatne DS, Leclerc T, Rafii A, Frayha H, Murugasu B, Wah LB, Sinniah R, Loubser M, Okamoto E, Al-Ghonaium A, Tufenkeji H, Abel L, Casanova JL. 2002. Inherited interleukin-12 deficiency: IL12B genotype and clinical phenotype of 13 patients from six kindreds. Am J Hum Genet 70:336–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach J, Rosenzweig S, Doffinger R, Dupuis S, Holland SM, Casanova JL. 2001. Mycobacterial diseases in primary immunodeficiencies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 1:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiling N, lscher CH, Fehrenbach A, Kröger S, Kirsching CJ, Goyert S, Ehlers S. 2001. Cutting edge: toll-like receptor (TLR)2- and TLR4-mediated pathogen recognition in resistance to airborne infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 2:3480–3484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remus N, El Baghdadi J, Fieschi C, Feinberg J, Quintin T, Chentoufi M, Schurr E, Benslimane A, Casanova JL, Abel L. 2004. Association of IL12RB1 polymorphisms with pulmonary tuberculosis in adults in Morocco. J Infect Dis 190(3):580–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig SD, Dorman SE, Uzel G, Shaw S, Scurlock A, Brown MR, Buckley RH, Holland SM. 2004. A novel mutation in IFN-gamma receptor 2 with dominant negative activity: biological consequences of homozygous and heterozygous states. J Immunol 173:4000–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanal O, Turul T, De Boer T, Van de Vosse E, Yalcin I, Tezcan I, Sun C, Memis L, Ottenhoff TH, Ersoy F. 2006. Presentation of interleukin-12/-23 receptor beta1 deficiency with various clinical symptoms of Salmonella infections. J Clin Immunol 26:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebban-Benin , Pescatore A, Fusco F, Pascuale V, Gautheron J, Yamaoka S, Moncla A, Valeria Ursini M, Courtois G. 2007. Identification of TRAF6-dependent NEMO polyubiquitination ites through analysis of a new NEMO mutation causing incontinentia pigmenti. Hum Mol Genet 16:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbina NV, Flynn JL. 1999. Early emergence of CD81 T cells primed for production of type 1 cytokines in the lungs of mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice. Infect Immun 67:3980–3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbina NV, Flynn JL. 2001. CD8 T cells participate in the memory immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 69:4320–4328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BRG, Silverman RH, Schereiber RD. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem 67:227–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet L, Zhang W, Torres-Fewell H. 2008. Mycobacterium avium glycolipids require specific acetylation and methylation patterns for signaling through TLR2. J Biol Chem 283:33221–33231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinchieri G. 2003. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptative immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 3:133–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufariello J, Chan J, Flynn J. 2003. Latent tuberculosis: mechanisms of host and bacillus that contribute to persistent infection. Infect Dis 3:578–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt G, Chapgier A, Yang K, Chuzhanova N, Feinberg J, Fieschi C, Boisson-Dupuis S, Alcais A, Filipe-Santos O, Bustamante J, de Beaucoudrey L, Al-Mohsen I, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Ghonaium A, Adimi P, Mirsaeidi M, Khalilzadeh S, Rosenzweig S, de la calle Martin O, Bauer TR, Puck JM, Ochs HD, Furthner D, Engelhorn C, Belohradsky B, Mansouri D, Holland SM, Schreiber RD, Abel L, Cooper DN, Soudais C, Casanova JL. 2005. Gains of glycosylation comprise an unexpectedly large group of pathogenic mutations. Nat Genet 37(7):692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Morse H. 2009. IRF8 regulates myeloid and B lymphoid lineage diversification. Immunol Res 43(1–3):109–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Wachter H. 1992. Iron modulates interferon-gamma effects in the human myelomonocytic cell line THP-1. Exp Hematol 20:605–610 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancoski J, Rocco C, Bernasconi A, Oleastro M, Bezrodnik L, Vrátnica C, Haerynck F, Rosenzweig SD. 2009. A 475 years-old founder effect involving IL12RB1: a high prevalent mutation conferring Mendelian susceptibility to micobacterial diseases in European descendants. Infect Genet Evol 9:574–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbe CS, Holland SM. 2005. Disseminated histoplasmosis in persons with interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency. Clin Infect Dis 41:e38–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan SY, Bustamante J, von Bernuth H, Casanova JL. 2008. From infectious diseases to primary immunodeficiencies. Immun Aller 28:235–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]