Abstract

Feed-forward inhibition from molecular layer interneurons onto granule cells (GCs) in the dentate gyrus is thought to have major effects regulating entorhinal–hippocampal interactions, but the precise identity, properties, and functional connectivity of the GABAergic cells in the molecular layer are not well understood. We used single and paired intracellular patch clamp recordings from post-hoc-identified cells in acute rat hippocampal slices and identified a subpopulation of molecular layer interneurons that expressed immunocytochemical markers present in members of the neurogliaform cell (NGFC) class. Single NGFCs displayed small dendritic trees, and their characteristically dense axonal arborizations covered significant portions of the outer and middle one-thirds of the molecular layer, with frequent axonal projections across the fissure into the CA1 and subicular regions. Typical NGFCs exhibited a late firing pattern with a ramp in membrane potential prior to firing action potentials, and single spikes in NGFCs evoked biphasic, prolonged GABAA and GABAB postsynaptic responses in GCs. In addition to providing dendritic GABAergic inputs to GCs, NGFCs also formed chemical synapses and gap junctions with various molecular layer interneurons, including other NGFCs. NGFCs received low-frequency spontaneous synaptic events, and stimulation of perforant path fibers revealed direct, facilitating synaptic inputs from the entorhinal cortex. Taken together, these results indicate that NGFCs form an integral part of the local molecular layer microcircuitry generating feed-forward inhibition and provide a direct GABAergic pathway linking the dentate gyrus to the CA1 and subicular regions through the hippocampal fissure

INDEXING TERMS: hippocampus, GABA, gap junction, perforant path, interneuron

The dentate gyrus is a region uniquely situated to control the effects of incoming cortical inputs on the hippocampus. The perforant path, formed by cells of layer II in the entorhinal cortex, constitutes the main input to the dentate gyrus (Steward, 1976; Varga et al., 2010). Although significant excitatory input arrives at the dentate through the perforant path, few granule cells (GCs) will fire to pass along this input to the CA3 region. This is due to the relatively low excitability of GCs, which is subserved both by the intrinsic properties of the GCs and also by the local GABAergic microcircuits within the dentate (Fricke and Prince, 1984; Mody et al., 1992a,b; Scharfman, 1992; Staley et al., 1992; Williamson et al., 1993; Coulter, 1999; Nusser and Mody, 2002; Pathak et al., 2007). The normal entorhinal–hippocampal circuit is involved in performing pattern separation and in spatial information encoding (Leutgeb et al., 2007; Moser et al., 2008), and, for both of these functions, the sparse firing of GCs is important.

Furthermore, the low excitability of dentate GCs has led to the region being referred to as the “dentate gate,” preventing overexcitation of the CA regions of the hippocampus under normal conditions (Andersen et al., 1966; Heinemann et al., 1992; Lothman et al., 1992; Behr et al., 1998; Hsu, 2007; Pathak et al., 2007) and possibly playing an important role in pathological conditions such as epilepsy, in which the gate function can transiently break down, allowing excessive excitation to reach the recurrent network of the CA regions (Heinemann et al., 1992; Lothman et al., 1992; Mody et al., 1992b; Sloviter and Brisman, 1995; Behr et al., 1998; Coulter, 1999; Ang et al., 2006; Hsu, 2007; Pathak et al., 2007). Thus, understanding the normal function of the dentate is crucial to understanding pathological conditions.

In the hilus and granule cell layers of the dentate gyrus, the microcircuits involving GABAergic interneurons and GCs have been explored, and both feed-forward and feedback interneurons onto GCs have been described (Buzsaki, 1984; Seress and Ribak, 1984; Sloviter, 1991; Freund and Buzsaki, 1996; Penttonen et al., 1997; Kraushaar and Jonas, 2000; Alle et al., 2001). However, although careful descriptions of individual molecular layer interneurons exist (Seress and Ribak, 1983; Soriano and Frotscher, 1989; Halasy and Somogyi, 1993; Han et al., 1993; Freund and Buzsaki, 1996; Chittajallu et al., 2007; Capogna, 2011), the precise identities of interneurons performing feed-forward roles in this layer have yet to be delineated. Because of the anatomical proximity of molecular layer interneurons to incoming perforant path input, feed-forward interneurons in the molecular layer would be expected to contribute to the sparse firing observed in dentate GCs. This role may be crucial in proper circuit function. Indeed, feed-forward inhibition has recently been shown to have dramatic computational effects on network dynamics (Ferrante et al., 2009).

For the molecular layer, we found that a subpopulation of interneurons was positive for markers matching the profile of cells belonging to the neurogliaform cell (NGFC) family, comprising NGFCs [originally described by Cajal as arachniform cells (Ramón y Cajal, 1999)] and ivy cells, which possess unique properties that have recently been described for the neocortex and CA3 and CA1 regions (Deller and Leranth, 1990; Vida et al., 1998; Tamas et al., 2003; Price et al., 2005, 2008; Simon et al., 2005; Houser, 2007; Olah et al., 2007; Szabadics et al., 2007, 2010; Elfant et al., 2008; Szabadics and Soltesz, 2009; Karayannis et al., 2010). Interneurons of the NGFC family release GABA from many sites into the extracellular space and can activate even extrasynaptic GABA receptors with a single action potential. This has led to the suggestion that cells of the NGFC family exhibit a unique type of neurotransmission separate from synaptic or electrical coupling—volume transmission (Olah et al., 2009; Capogna & Pearce, 2011). NGFCs induce both a slow GABAA-mediated as well as delayed and prolonged GABAB-mediated current, resulting in a large charge transfer upon stimulation (Tamas et al., 2003; Szabadics et al., 2007). Such properties enable these cells to mediate slow but long-lasting, powerful control of their targets. Additionally, whereas most interneurons form electrical synapses only with other cells of the same type, NGFCs are known to form promiscuous gap junctions with other interneuronal types, perhaps enabling them to coordinate the activity of diverse players in local inhibitory microcircuits (Simon et al., 2005; Zsiros and Maccaferri, 2005, 2008; Olah et al., 2007). A feed-forward interneuron with the unique features of the NGFC in the molecular layer would be well-suited to play a role in maintaining strict control of GC excitability.

The diversity of molecular layer interneurons, particularly insofar as these cells may correspond to known cell types, has not been fully explored, and here we identify and characterize NGFCs as a specific interneuronal subtype present in the dentate molecular layer. Defining such specific microcircuitry in this region will aid in understanding the normal dentate and how and why it may change in pathological conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and female adolescent (3–5 weeks postnatal) Wistar rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were deeply anesthetized with isofluorane for acute hippocampal slice electrophysiology and subsequent immunocytochemistry. All experimental protocols involving animals were reviewed and approved by the UC Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Electrophysiology

Cells were recorded from acute horizontal hippocampal slices (350 µm) from the ventral hippocampal formation prepared in ice-cold sucrose solution (containing in mM: 85 NaCl, 75 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 25 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 4 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 24 NaHCO3), incubated for 1 hour at 32°C, and stored at room temperature until recording in ACSF (containing in mM: 126 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose). Slices were visualized using an Eclipse FN-1 (Nikon) microscope with infrared (750 nm) Nomarski differential interference contrast optics (Nikon 40XNIR Apo N2 NA0.8W WD3.5 objective with ×1.5 magnification lens) and recorded at 36°C ± 0.5°C. Unless otherwise specified, whole-cell somatic recordings were made using 3–5 MΩ borosilicate glass pipettes filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM): 90 K-gluconate, 1.8 NaCl, 1.7 MgCl2, 27.4 KCl, 0.05 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgATP, 0.4 Na2GTP, 10 phosphocreatine, and 8 biocytin (pH 7.25, 270–290 mOsm). Recordings were made and controlled using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA), and Clampex software (version 9.2; Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA).

Drug application

Drugs were obtained from Tocris (Ellisville, MO), dissolved in ACSF, and bath applied at the following concentrations: 10 µM D-APV, 5 µM NBQX, 50 nM CGP55845, 5 µM gabazine (SR95531).

Intrinsic properties

Recordings were used only from cells originally patched and recorded in normal ACSF and confirmed as NGFCs by both firing pattern and axonal morphology (see below). Input resistance was calculated from the steady-state voltage change induced by the last 300 msec of a small (−20 pA) 1-second hyperpolarizing current step. Sag was measured by comparing the negative voltage peak during the first 100 msec of a −100 pA 1-second hyperpolarizing pulse with the steady-state voltage during the last 300 msec of the same pulse. Membrane time constant was measured from the best fit single exponential curve of the voltage response to the beginning of a −100-pA step. Action potential properties were determined for the first three spikes elicited in a cell and averaged.

Paired recordings

Presynaptic interneurons were held near −60 mV in current clamp. One or two short [2-msec duration; 2.5-msec interstimulus interval (ISI)] current pulses were delivered to evoke single or dual action potentials. Postsynaptic cells were held in voltage clamp. To establish whole-cell recordings for pairs, an extracellular solution with low Ca2+ concentration (0.15 mM) was typically used to patch the NGFC to avoid overexcitation during patch formation (Tamas et al., 2003); once the preparation was stable, whole-cell recording was achieved in the NGFC and the presumed postsynaptic cell, and the perfusate was switched to ACSF containing normal extracellular [Ca2+] to test for connections between the cells. Sweeps from individual experiments were averaged, and analyses of kinetics were performed from averaged traces. Amplitude, 10–90% rise time, and decay time constant were measured for GABAA at −90 mV, where GABAB is close to its reversal potential. For GABAB kinetics, current response in the GABAB antagonist CGP55845 was normalized by the GABAA peak in normal ACSF with the postsynaptic cell at −50 mV and subtracted to give an approximation of the GABAB component alone. Additionally, a measure of the magnitude of the GABAB response was given by the area under the GABAB portion of the curve. The current recorded in whole-cell voltage clamp mode in the postsynaptic cell was expressed as a percentage of the hyperpolarizing current injected into the presynaptic cell to generate the average coupling coefficient of electrically coupled interneurons.

Field stimulation and spontaneous postsynaptic current measurements

Constant-current stimuli (10 µsec) were applied at 0.1 Hz through a bipolar 90-µm tungsten stimulating electrode placed in the subiculum within 100 µm of the hippocampal fissure. A stimulus isolator (WPI A360D) was used to gradually increase the stimulus strength until a stable response could be observed. To ensure that only monosynaptic responses were considered, data were rejected if the latency between stimulation and response was greater than 3 msec. Paired pulses were delivered at ISIs of 50, 100, 150, or 200 msec. Once a stable amplitude inward current had been established in control conditions, evoked responses were recorded in ACSF with sequential and additive washes in of gabazine and CGP55845 together, D-APV, and finally NBQX; in each case, at least 15 sweeps after wash-in were averaged, and changes in current amplitude were normalized to amplitude in normal ACSF. In a subset of field stimulation experiments, NBQX was washed out until the inward current reappeared (10–20 minutes). The responses elicited by paired perforant path stimulations were normalized to the amplitude of the first peak, and paired-pulse ratio was expressed as a ratio of second:first peak amplitude.

Spontaneous postsynaptic current (sPSC) frequencies in NGFCs and GCs were determined from 1-minute-long data segments in normal ACSF. Analysis of sPSCs was performed using the MiniAnalysis program (version 6.0.7; Synatptosoft) with visual inspection of detected events. For sIPSC analysis, cells were patched using a CsClbased internal solution (containing, in mM: 40 CsCl, 90 K-gluconate, 1.8 NaCl, 1.7 MgCl2, 3.5 KCl, 0.05 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 MgATP, 0.4 Na2GTP, 10 phosphocreatine, 8 biocytin, pH 7.2, 270–290 mOsm) in ACSF containing D-APV and NBQX.

Cell identification

NGFCs were positively identified based on firing properties, synaptic characteristics, and axonal morphologies. In cases of individual NGFCs, a late-spiking firing pattern with hyperpolarized (near −75 mV) RMP, a relatively fast time constant, and little to no sag during hyperpolarizing pulses were suggestive of NGFC identity; however, all neurons were recovered with diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining (see below), and the axon was inspected for the characteristic dense arborization and frequent en passant boutons. Cells were discarded if the axon could not be inspected. In the case of paired recordings between NGFCs and GCs, NGFCs were included without DAB axon recovery only if they elicited a GABAB current in the postsynaptic cell with a single presynaptic spike, because this property is unique to cells of the NGFC family (Tamas et al., 2003). GCs were identified by their distinct firing pattern and location in the granule cell layer. Parvalbumin (PV)-expressing basket cells (PVBCs) were identified by their fast spiking firing pattern, PV immunocytochemistry, and basket cell axonal morphology in the granule cell layer by DAB.

Immunocytochemistry and morphology

Slices were immediately fixed postrecording in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% picric acid for 24–48 hours at 4°C and were resectioned at 60 or 100 µm. For 60-µm sections, primary antibodies were used at 1:1,000 concentration: PV (polyclonal rabbit antibody; Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland), neuropeptide Y (NPY; polyclonal rabbit antibody; Bachem, Torrance, CA), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS; polyclonal rabbit antibody; Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), COUP TFII (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2; monoclonal anti-human mouse antibody clone H7147; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and reelin (monoclonal a.a. 164–496 mouse antibody clone G10; Millipore, Bedford, MA). Slices were incubated overnight in TBS buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and 2% normal goat serum. Immunoreactions were revealed using Alexa-488 or Alexa-594-conjugated secondary goat antibodies against rabbit or mouse, and biocytin was revealed using Alexa-350-conjugated streptavidin. All sections were processed (with or without immunocytochemistry) to reveal the fine details of morphology using a conventional DAB staining method. Briefly, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 1% H2O2, and slices were incubated with ABC (avidin-bio-tin complex) reagent (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 0.1% Triton X-100. The reaction was developed with DAB and NiCl2 for 8–15 minutes and stopped with H2O2 solution. Sections were dehydrated and mounted. Cells were visualized with conventional transmitted light microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop 2). Camera Lucida drawings were made from either a single, representative 100-µm section or reconstructed from serial 60-µm sections using a ×100 oil immersion objective. Interbouton distances were measured by light microscopy in six different fields of view (each 87 × 65 µm) per cell from seven different confirmed NGFCs.

Statistical analysis

Average values are expressed as mean ± SEM. All wash-in experiments and paired-pulse amplitudes were compared by two-tailed paired t-tests. All experiments comparing groups of different cells were compared by two-tailed unpaired t-tests.

Antibody characterization

For all antibodies used in this study, the pattern of expression in hippocampal slices was compared with previously published results as cited in Table 1 and detailed below and was consistent with these expression patterns.

TABLE 1.

Antibody Characterization

| Name | Structure of immunogen | Manufacturer and catalog No. | Species | Clonality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COUP TFII | Human COUP TFII amino acids 43–64 | Invitrogen; PP-clone H7147-00 | Mouse | Monoclonal |

| nNOS | Recombinant human nNOS amino acids 1422–1433 | Cayman; 160870 | Rabbit | Polyclonal |

| NPY | Antigen sequence: H-YPSKPDNPGEDAPA EDMARYYSAKRHY INLITRQRY-NH2 | Bachem; T-4070.0050 | Rabbit | Polyclonal |

| PV | Rat muscle PV | Swant; PV-28 | Rabbit | Polyclonal |

| reelin | Recombinant reelin amino acids 164–496 | Millipore; AB5364 clone G10 | Mouse | Monoclonal |

Specificity data

Coup-TFII

The antibody was tested in a knockout (KO) mouse (Qin et al., 2007); in this paper, embryonic, P0, P7, and P21 cerebellum sections of COUP-TFII conditional knockout mice [generated by Cre recombination of a COUP-TFII gene flanked by Flox sites (F/F), with Cre expression driven by the neuron-specific enolase (NSE) promoter] were compared with the null mutant, and knockout (KO) animals did not express COUP-TFII. Additionally, the expression pattern in hippocampus was similar to published hippocampal expression patterns (Fuentealba et al., 2010).

nNOS

The antibody was tested in a KO mouse with targeted disruption of nNOS exon 2 in heart tissue, where no staining was observed in the KO (Dawson et al., 2005). Labeling pattern in the hippocampus was also similar to that seen with other nNOS antibodies (Fuentealba et al., 2008; Tricoire et al., 2010).

NPY

The antibody was tested by the manufacturer and in addition was tested in a tetracycline-driven conditional KO mouse in which levels of mRNA and protein were reduced to <15% of control animals’ levels of mRNA and protein after 9 weeks of doxycycline treatment, and the antibody staining of the brain was comparably reduced at that time point (Ste. Marie et al., 2005). The expression pattern of NPY was also similar to published literature on NPY expression in the hippocampus (Deller and Leranth, 1990; Karagiannis et al., 2009; Tricoire et al., 2010).

PV

The antibody was tested by Western blot in normal and KO mice by using tissue from three different muscle groups (panniculus carnosus, extensor digitorum longus, and abdominal muscles), revealing a single band representing PV on Western blot with this antibody (Schwaller et al., 1999). Additionally, the expression pattern matched published data on PV-expressing neurons in the hippocampus (Kosaka et al., 1987).

Reelin

This antibody was tested by ELISA and Western blot against different epitopes of the reelin protein. This antibody recognized the H epitope near the N terminus of the protein (de Bergeyck et al., 1998). Additionally, it was tested and showed no staining in the reeler mouse, a mouse with a large mutation within the reelin protein, and was also tested in the Orleans reeler mouse, which has a different C terminal frameshift mutation but a normal N terminus, in which staining was present (de Bergeyck et al., 1997). Furthermore, the expression pattern of this antibody was consistent with published hippocampal expression patterns of reelin (Pesold et al., 1998).

RESULTS

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings of NGFCs were made in 57 acute slices from 42 animals, yielding a total of 60 confirmed recorded NGFCs in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus to be used for this study. During recording, putative NGFCs were identified by firing pattern and filled with biocytin for post hoc identification. All 60 cells were confirmed either by axonal morphology or, for a subset (n = 2) of NGFC–GC pairs, by ability to elicit a GABAB response with a single action potential (see Materials and Methods).

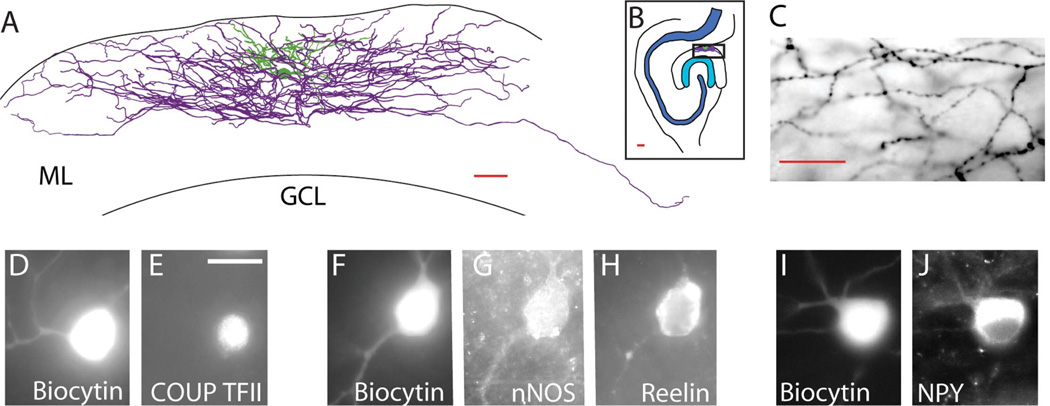

Single-cell characteristics of dentate gyrus NGFCs

Dentate NGFCs had a typical, very dense arborization that could be appreciated in 100-µm representative sections of recorded slices (Fig. 1A; location of cell in horizontal slice shown in Fig. 1B) with frequent (average interbouton distance 2.3 ± 0.08 µm; n = 1,930 interbouton intervals from 42 fields of view from seven cells) en passant boutons (Fig. 1C). Filled NGFCs in the dentate contained a number of markers typical of NGFCs in other brain areas, including COUP TFII (n = 16 of 19 tested cells; Fig. 1D,E), nNOS (n = 12 of 16 tested cells; Fig. 1F,G), reelin (n = 10 of 10 tested cells; Fig. 1F,H), and NPY (n = 9 of 31 tested cells; Fig. 1I,J). Note that these numbers likely underestimate the true presence of cellular markers in this population, because, although a positive immunoreaction is conclusive, intracellular recording allows both dilution of intracellular markers by pipette solution and leakage of cellular contents from the disrupted membrane after the withdrawal of the pipette, which can lead to a false negative, particularly for weakly staining cytoplasmic markers such as NPY.

Figure 1.

Characteristic morphologies and immunocytochemical profiles of NGFCs in the dentate. A: Camera lucida drawing from a representative 100-µm section of a dentate NGFC. B: Position of the cell shown in A within the horizontal hippocampal section. ML, molecular layer; GCL, granule cell layer. C: Light microscopic view (×100) of the characteristic axonal arborization of the cell shown in A showing multiple axonal branches passing through a single plane of focus and frequent, small en passant boutons. D–J: Recorded and confirmed NGFCs in the dentate filled with biocytin (×100) express a variety of NGFC markers, including COUP TFII (D,E), nNOS (F,G), and reelin (G), and NPY (H–J). Each image represents a single fluorescent channel, with biocytin indicating the recorded cell (D,F,I) and the adjacent panels indicating individual antibody labeling in the same plane of focus (E,G,H,J). The brightness and contrast of these images were digitally adjusted to provide maximal visualization of the markers. Scale bars = 20 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

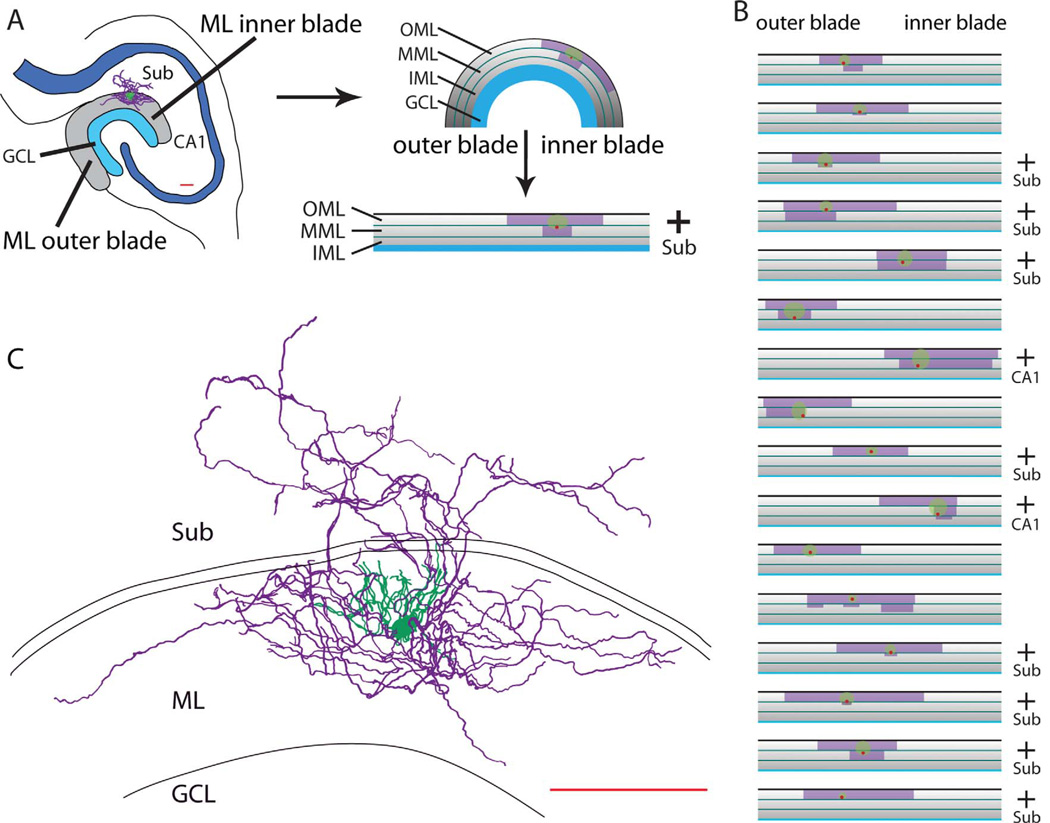

Among 11 NGFCs in which the origin of the axon within the dense axonal cloud could be determined with particular clarity, five originated from a dendrite and six originated from the cell body. The axon of dentate NGFCs typically spanned hundreds of micrometers along the outer border of the dentate gyrus, primarily in the middle and outer molecular layers but occasionally passing into the inner molecular layer. In 11 of 17 cells that had axons and dendrites that could be especially well visualized after DAB processing, the axon, but not the dendrite, extended into the subicular and CA1 regions (Fig. 2A–C). In contrast, GC dendrites never extended across the hippocampal fissure to the subiculum or to the CA1 region. To summarize the location of NGFCs and the extent of their axons and dendrites in horizontal sections, the same 17 cells were examined under the light microscope and their axonal and dendritic arborizations plotted onto a flattened representation of the layers of the dentate gyrus molecular layer (Fig. 2A,B). Axonal arbors of NGFCs on average covered 37.7% ± 1.8% of the total length (1,122.9 ± 62.4 µm) of the molecular layer in horizontal sections, as measured from inner to outer leaflet parallel to the granule cell layer. Cell bodies of NGFCs were located in middle (n = 8) and outer (n = 9) molecular layers. Compared with the extensive axonal cloud, dendritic fields were small, extending only tens of micrometers from the cell body within the middle and outer molecular layers, only occasionally extending into the inner molecular layer and never extending into the granule cell layer or across the hippocampal fissure.

Figure 2.

Extent of dentate NGFCs within and beyond the molecular layer. A: Example of a subiculum-projecting NGFC (reconstructed in C), in which the locations of the soma, dendritic tree, and axonal arbor were measured and plotted onto an arc of the molecular layer (ML). The arc was flattened and divided into outer (O; top), middle (M), and inner (I; bottom) layers to produce an overview map of single NGFCs: locations of cell bodies (red dots; n = 8 in MML, n = 9 in OML), dendritic fields (green circles), and axonal clouds (purple boxes). Sub, subiculum; GCL, granule cell layer. The presence of axons within the subiculum is indicated by a plus sign to the right of the map. B: Plots of 16 additional NGFCs in the dentate, constructed as shown in A. The axonal arbors covered, on average, 37.7% ± 7.5% of the total length of the molecular layer, which was, on average, 1, 122.9 ± 3.9 µm in length. Note that 11 of the 17 measured cells had axons projecting across the hippocampal fissure into the subiculum or CA1 regions (indicated by a plus sign to the right of the map). C: Camera lucida reconstruction of the subiculum-projecting NGFC mapped in A. Soma and dendrites are in green, axon in purple. Scale bars = 100 µm.

Intrinsic properties were analyzed in a subset of recorded neurons (n = 21) that originally had been patched and recorded in normal ACSF solution and had a stable resting membrane potential in current clamp with no current injection. Intrinsic properties were comparable to those seen in other brain areas and species (Povysheva et al., 2007; Tricoire et al., 2010). NGFCs had a characteristically late firing pattern, often exhibiting a ramp in membrane potential prior to firing action potentials (Fig. 3A, top trace), a resting membrane potential of −75.6 ± 0.9 mV, a threshold of −30 ± 1 mV, an input resistance of 147 ± 8 MΩ, a membrane time constant of 6.81 ± 0.36 msec, and essentially no sag (0.17 ± 0.10 mV) in response to a −100 pA hyperpolarizing step. Because there was no sag, the measurement of the membrane time constant in response to a −100 pA pulse was not complicated by this parameter.

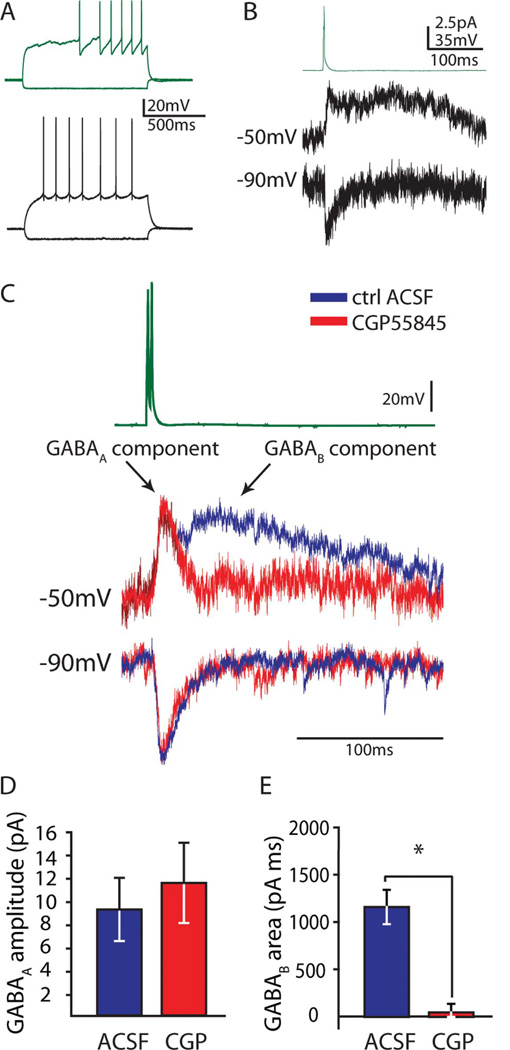

Figure 3.

NGFC output to GCs. A: Characteristic firing patterns of a dentate NGFC (top traces) and GC (bottom traces) showing the NGFC’s slight depolarizing ramp with late firing and unique afterhyperpolarization shape. B: Average postsynaptic current responses in granule cells voltage clamped at −50 mV (middle trace, n = 9 pairs) or −90 mV (bottom trace, n = 7 pairs) following a single action potential in presynaptic NGFCs (top trace). Note that the early ionotropic GABAA component is outward at −50 mV and inward at −90 mV and that the slow metabotropic GABAB component is not visible at −90 mV, close to its reversal potential. C: The late GABAB component can be abolished by the GABAB antagonist CGP55845, as demonstrated in averaged traces (n = 3 pairs), normalized to control GABAA peak (traces organized as in B). D,E: The GABAB antagonist CGP55845 has no effect on the amplitude of GABAA currents (P = 0.16), but the GABAB component of the postsynaptic response (measured as area under the GABAB curve after the GABAA response has returned to baseline) is abolished by the CGP55845 (*P = 0.02). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

NGFC output to GCs

Among 59 paired recordings of molecular layer interneurons with late-spiking firing patterns and GCs, 32 were connected (54%) and 14 connected pairs were confirmed as NGFCs (see Materials and Methods); 11 of the 14 connected NGFC pairs could be observed with a single presynaptic action potential. No GC to NGFC connections were observed in any of the 59 paired recordings.

Paired recordings between NGFCs in the molecular layer and GCs demonstrated characteristic biphasic postsynaptic responses consisting of two components, an early GABAA mediated response and a late-appearing prolonged GABAB component (Fig. 3B; n = 9 used for analysis, n = 2 identified only by GABAB component). These two components could be separated in two ways, by reversal potential and pharmacologically. The early ionotropic GABAA component was outward at −50 mV and inward at −90 mV (Fig. 3B,C). The GABAB component, mediated by a metabotropic and therefore slower K+ current, appeared as a late prolonged outward current at −50 mV but not at −90 mV, close to its reversal potential.

This late GABAB component, but not the early GABAA component, could also be blocked by the specific GABAB antagonist CGP55845 (Fig. 3C–E; n = 4).

The late component of the postsynaptic current response was examined with the postsynaptic GC held in voltage clamp at −50 mV. At this potential, both the GABAA and GABAB currents were outward in nature. Because single action potentials in dentate NGFCs generated very-small-amplitude responses in GCs, we used two action potentials in quick succession (2.5-msec ISI) to generate larger responses that could be examined more easily for quantification of the effects of CGP. The increase in GABAA amplitude and the area of the GABAB component were compared by the ratio of the response to two action potentials vs. one action potential (2AP:1AP ratio) in NGFC to GC pairs. The 2AP:1AP ratio for GABAA current amplitude was 2.4 ± 0.5 (n = 7; P = 0.03) and for the area under the GABAB current was 2.6 ± 0.5 (n = 7; P < 0.01), demonstrating that both components exhibit significant facilitation with 2APs. This facilitation allowed us to investigate the nature of the late component of the biphasic response more easily. To confirm that the GABAB receptor was responsible for the late component, two action potentials were used to elicit a large response, and the area under the GABAB curve from the end of the GABAA response to the end of the GABAB response was compared before and after wash-in of the GABAB antagonist CGP55845. In these experiments, the late component was abolished by CGP55845 (n = 4; late component area in ACSF 1,143.6 ± 178.4 pAms, in CGP55845 49.5 ± 89.7 pAms; P = 0.02), demonstrating that the late component was, indeed, mediated by GABAB receptors. In a subset of cases in which a clear GABAB response was elicited with a single action potential (Fig. 3B; n = 3), CGP55845 was used to estimate the kinetics of the GABAB current. To do so, the remaining average GABAA response to a single NGFC action potential in the presence of CGP55845 was subtracted from the average biphasic GABAA- and GABAB-mediated response in normal ACSF to generate an estimate of unitary GABAB current alone (10–90% rise time 71.5 ± 6.8 msec, decay from peak to 50% amplitude 94.3 ± 8.6 msec, amplitude 8.99 ± 1.14 pA, area under GABAB curve 963.1 ± 241.5 pAms). Note that, for CGP55845, the kinetics of the GABAA responses to 1AP were not significantly changed between control and CGP as measured at −90 mV (n = 3; 10–90% rise time in ACSF 4.2 ± 0.6 msec, in CGP 6.9 ± 2.5 msec, P = 0.34; decay tau in ACSF 19.0 ± 7.0 msec, in CGP55845 16.2 ± 10.1 msec, P = 0.46) or at −50 mV (n = 3; 10–90% rise time in ACSF 11.6 ± 4.2 msec; in CGP55845 11.6 ± 4.0 msec; P = 0.98).

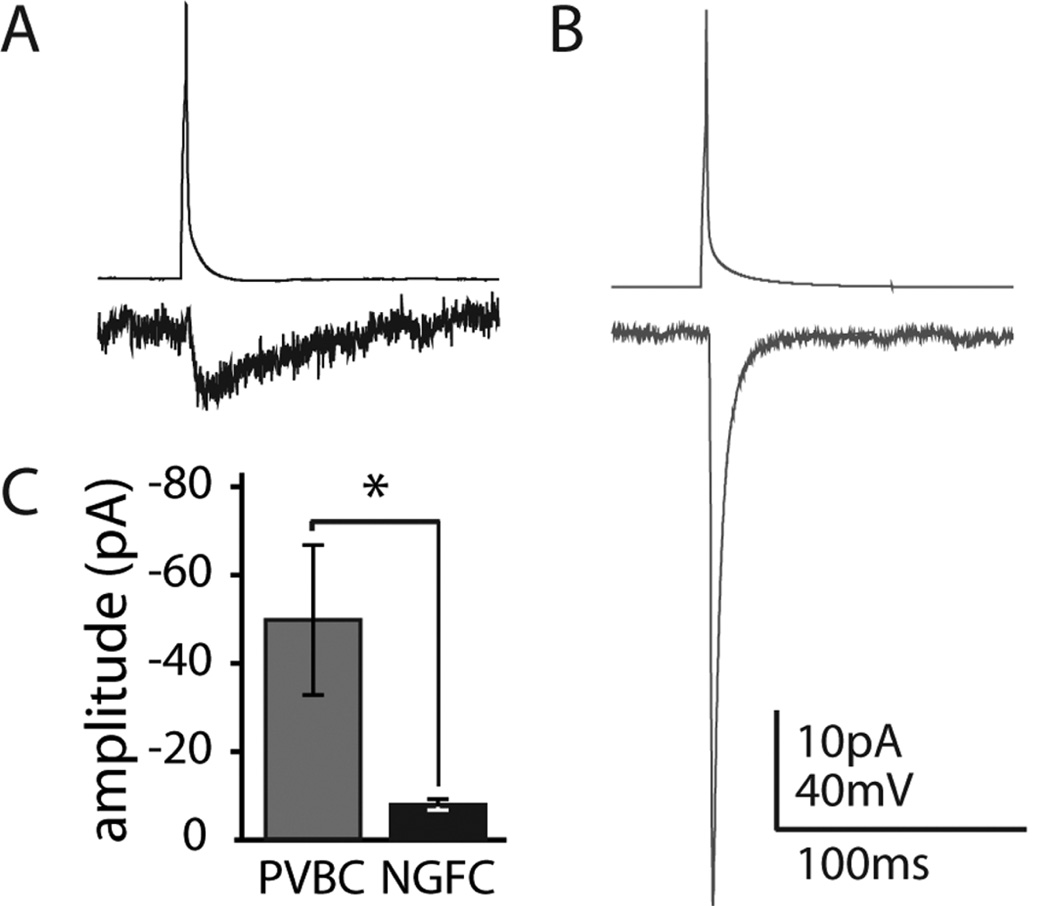

Unitary GABAA kinetics were measured by using one presynaptic action potential with the postsynaptic GC held in voltage clamp at −90 mV. Responses generated by NGFCs (Fig. 4A) were characteristically slower (n = 7; NGFCs 10–90% rise time 5.8 ± 1.1 msec, decay time constant 14.7 ± 3.6 msec) and much smaller in amplitude (NGFC amplitude −8.01 ± 1.22 pA) than responses generated by PV-positive fast spiking basket cell (PVBC) to granule cell connections (Fig. 4B; n = 5 PVBCs; 10– 90% rise time 0.99 ± 0.12 msec, decay time constant 4.1 ± 0.7 msec, amplitude −46.12 ± 15.41 pA). However, although the amplitude of the unitary response to PVBCs at the soma was more than 475% greater than the NGFC response (Fig. 4C; P = 0.01), the overall charge transfer of the PVBC response was comparable to the NGFC response (area under IPSC curve for PVBCs −237.5 ± 81.2 pAms, for NGFCs −140.1 ± 29.4 pAms; P = 0.23), underscoring the importance of the prolonged nature of the inhibition generated by NGFCs.

Figure 4.

NGFC vs. PVBC responses in GCs. Average currents in GCs held in voltage clamp at −90 mV (bottom traces) elicited by a single action potential (top traces) in NGFCs (n = 7 pairs; A) or PVBCs (n = 5 pairs; B) demonstrate the significant difference in the amplitude of the responses measured at the GC soma (*P = 0.01; C). Note that, because of the prolonged nature of the response to NGFCs, the inhibitory charge transfer, as measured by the area under the response at −90 mV, is comparable (see text; P = 0.30).

Inputs to dentate NGFCs

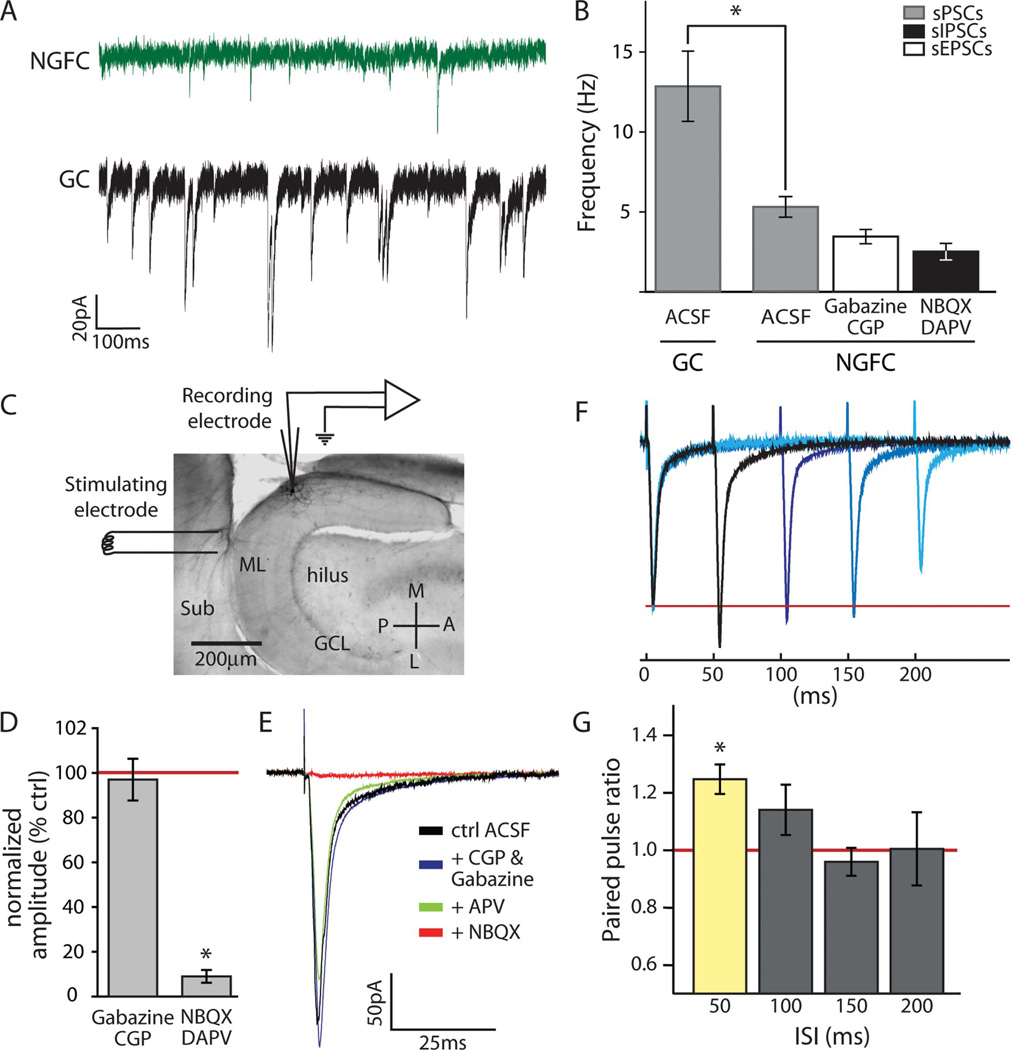

Fewer spontaneous events were observed in NGFCs (5.3 ± 0.6 Hz; n = 6) held in voltage clamp at −80 mV in control ACSF compared with dentate granule cells (Fig. 5A,B; 12.9 ± 2.2 Hz; n = 6; P < 0.01), which is consistent with their smaller dendritic fields. When the GABA receptor antagonists gabazine and CGP55845 were washed into the bath, the spontaneous event frequency in NGFCs was reduced by 31.9% ± 7.8% (P = 0.02), revealing an sEPSC frequency in these cells of 3.6 ± 0.5 Hz. To examine specifically the rates of sIPSCs in NGFCs compared with GCs, a CsCl-based internal solution with a high [Cl−] was used in conjunction with the glutamate receptor antagonists D-APV and NBQX. Under these conditions, the rate of sIPSCs in NGFCs was 2.6 ± 0.5 Hz (n = 4), still significantly less than sIPSC frequency in GCs (9.1 ± 1.9 Hz; n = 8; P = 0.04).

Figure 5.

Inputs to dentate NGFCs. A: Example traces of sPSCs in an NGFC (top trace) and a GC (bottom trace). B: Quantification of sPSCs in GCs (n = 6) and NGFCs (n = 6), demonstrating that NGFCs receive significantly fewer spontaneous inputs than GCs (*P < 0.01). sPSCs were further separated into excitatory (EPSC; n = 6; 3.6 ± 0.5 Hz) and inhibitory (IPSC; n = 4; 2.6 ± 0.5 Hz) events using the GABA antagonists CGP55845 and gabazine or the glutamate receptor antagonists NBQX and D-APV, respectively. C: Experimental setup for field stimulation experiments. A stimulating electrode was placed on the subicular side (Sub) of the hippocampal fissure to stimulate the perforant path, and a patch pipette was used to record responses in molecular layer (ML) NGFCs. GCL, granule cell layer; P, posterior; A, anterior; M, medial; L, lateral. D,E: An inward current mediated primarily by AMPA channels was observed in NGFCs in response to perforant path stimulation. Specific antagonists were bath applied sequentially, beginning with GABA antagonists CGP55845 and gabazine, followed by the NMDA antagonist D-APV, and finally by the AMPA antagonist NBQX. Quantification (D) and an example (E) of wash-in data are presented. D: Quantified data were normalized to response amplitudes in normal ACSF. Perforant path input was not blocked by GABA antagonists (CGP55845 and gabazine; n = 8; P = 0.49) but was abolished by glutamate antagonists (NBQX and D-APV; n = 10; *P < 0.01). E: In the example traces, the stimulation artifact (truncated) is followed by an inward current that persisted in GABA and NMDA antagonists but was abolished by the AMPA antagonist NBQX. F,G: Perforant path input exhibits facilitation at 50 msec, but not longer interstimulus intervals (ISIs). Paired-pulse ratio was expressed as the second peak:first peak amplitude. F: Example traces are averaged responses in a single NGFC to paired pulses of varying ISIs (overlaid). G: Quantification of paired perforant path stimulation reveals a significant facilitation at 50 msec ISI (n = 5; *P < 0.01) but not at 100 (n = 5, P = 0.17), 150 (n = 5, P = 0.54), or 200 msec (n = 5; P = 0.93) ISIs. Scale bar = 200 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

To examine specific inputs to NGFCs, field stimulation of perforant path fibers on the subicular side of the hippocampal fissure was performed (Fig. 5C). Perforant path stimulation induced an inward current in dentate NGFCs held in voltage clamp at −75 mV (Fig. 5D,E; n = 11). This current was not blocked by sequential wash-in of the GABA antagonists gabazine and CGP55845 (P = 0.49) nor the NMDA antagonist D-APV (P = 0.09) but was abolished by the AMPA antagonist NBQX (Fig. 5D,E; P < 0.01; amplitudes, normalized to amplitude in normal ACSF, in gabazine and CGP55845 97.0% ± 9.3%, n = 8; in GABA antagonists + D-APV 71.1% ± 13.2%, n = 4; in GABA antagonists + D-APV + NBQX 9.0% ± 2.9%, n = 10). In a subset of the experiments (n = 3), partial washout of NBQX was performed to ensure that perforant path evoked responses would reappear (washout required −15 minutes). Paired-pulse stimulation of the perforant path resulted in facilitation with a 50-msec ISI (Fig. 5F,G; n = 5; PP ratio = 1.26 ± 0.05; P < 0.01) but not at longer ISIs (Fig. 5F,G; PP ratio at 100 msec = 1.15 ± 0.09, P = 0.17; 150 msec = 0.97 ± 0.05, P = 0.54; 200 msec = 1.01 ± 0.13, P = 0.93).

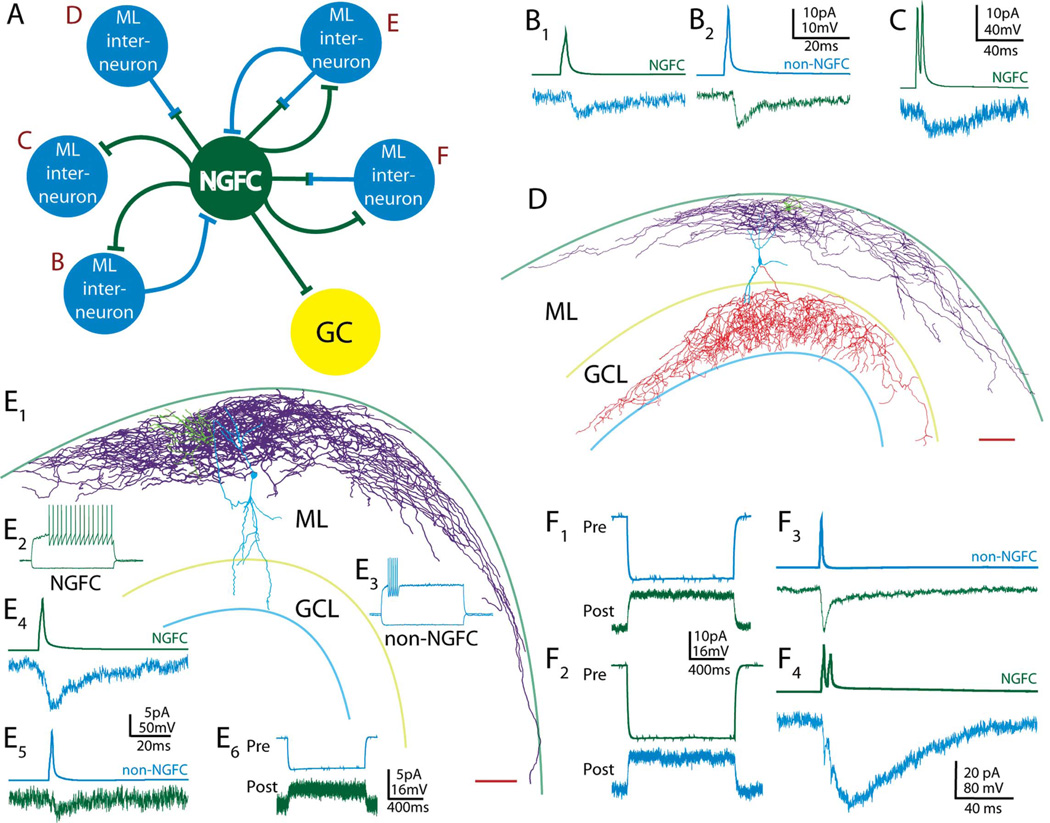

NGFCs form diverse synapses with diverse cells

Finally, we investigated the local microcircuits in which NGFCs participate within the molecular layer. For all interneuronal connections, at least one cell of the pair was recovered and identified as an NGFC by using axonal morphology. NGFCs form both chemical and electrical connections with other interneurons, so we tested pairs for each type of connection. Chemical synaptic connections had longer durations and delays to peak of >3 msec, whereas electrical connections had shorter durations, had delays to peak of < 3 msec, and could also be observed by injecting a hyperpolarizing current into the presynaptic cell, resulting in an outward current in the postsynaptic cell. Among the recorded confirmed NGFC to interneuronal pairs, 11 of 14 (79%) were connected. All possible two-cell connection motifs were observed (Fig. 6A), including synaptic only (Fig. 6B,C; n = 3), electrical only (Fig. 6D; n = 4), and both synaptic and electrical (Fig. 6E,F; n = 4). NGFCs were repeatedly observed to form electrical synapses with other types of molecular layer interneurons (n = 6), which were confirmed as non-NGFCs by firing pattern and/or morphology (Fig. 6C,D). The electrical coupling coefficient (the percentage of the current injected at the presynaptic soma that could be observed as an outward current at the postsynaptic soma) in these pairs was 3.85% ± 0.89% on average [comparable to coupling coefficients observed in animals of similar ages in various brain areas and cell types (Amitai et al., 2002; Meyer et al., 2002; Price et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2005)]. Among the 11 total pairs, both neurons could be positively identified as either NGFCs or non-NGFCs in nine pairs; two pairs were between two NGFCs, and seven pairs were between NGFCs and non-NGFCs. Some examples and a summary of the diversity of connectivity of dentate NGFCs observed in these experiments are given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Specific examples of the diverse interneuronal connections of NGFCs. A: Several different connectivity motifs were observed between NGFCs and other molecular layer (ML) interneurons, either other NGFCs or non-NGFCs. In each case, at least one cell of the pair (in each case, shown in dark green) could be positively identified as an NGFC. Each observed motif is lettered B–F, and B–F represent examples corresponding to these letters. The numbers of observations of each motif were as follows: B, n = 2; C, n = 1; D, n = 4; E, n = 1; F, n = 3. B: Bidirectional synaptic connection from NGFC to non-NGFC (B1) and non-NGFC to NGFC (B2). C: Unidirectional NGFC to molecular layer interneuron synaptic connection. D: Camera lucida reconstruction of an electrically connected NGFC to non-NGFC pair (0.6% coupling coefficient, electrophysiology not shown), demonstrating heterologous electrical coupling between two distinct cell types. NGFC soma and dendrites are in green, NGFC axon in purple, non-NGFC soma and dendrites in blue, and non-NGFC axon in red. Reference lines represent the outer edge of the molecular layer and the borders of the granule cell layer (GCL). E: Camera lucida reconstruction (E1) and electrophysiology (E2–6) from an electrically and synaptically connected NGFC to non-NGFC pair (color scheme and scale bar as in D, non-NGFC axon not recovered). Electrophysiology: firing pattern of NGFC (E2; dark green, left) and non-NGFC (E3; light blue, right); NGFC (green; E4) to non-NGFC (blue) chemical synaptic connection; non-NGFC to NGFC chemical synaptic connection (E5) and electrical connection (E6); electrical connections revealed by injecting a −100-pA hyperpolarizing current into one presynaptic (Pre) cell (top, blue) and observing an outward current in a postsynaptic (Post) cell (bottom) held in voltage clamp at −75 mV. Electrical coupling coefficient for this pair was 2.3% (see text). F: Example of a NGFC to non-NGFC pair with an electrical coupling coefficient of 7.8% and a unidirectional chemical synaptic connection. The electrical connection was revealed bidirectionally (F1,2) as described for E. For chemical synaptic connections (F3,4) single or dual action potentials were elicited in the presynaptic cell (upper traces), eliciting (lower traces) an electrically mediated response in the postsynaptic NGFC (F3; green), and both an electrically and chemical synaptically mediated current in the postsynaptic non-NGFC (F4; blue). Note that, in this pair, the difference between electrical and chemical synaptic currents can be clearly seen as two nearly instant peaks representing the electrical connection riding on the rise of the delayed, larger amplitude chemical synaptic current. Scale bars = 100 µm.

DISCUSSION

Cells of the NGFC family (including both NGFCs and ivy cells) have emerged as major players in the microcircuitry of many brain areas, providing a unique type of slow but powerful inhibition and forming connections with numerous and diverse neuronal types. Estimates suggest that nearly 40% of interneurons in the hippocampus are NPY-and nNOS-positive cells that are likely a part of this family (Fuentealba et al., 2008). Neurogliaform family cells have been hypothesized to play important roles in modulating spike timing, neuronal synchrony, generation of oscillations, strength of feedforward inhibition, tonic inhibition, and perhaps even neurovascular control through release of NO (Tamas et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2005; Zsiros et al., 2007; Fuentealba et al., 2008; Price et al., 2008; Olah et al., 2009; Karayannis et al., 2010).

Here we have described NGFCs in the dentate gyrus for the first time. We have characterized their intrinsic properties, including their hyperpolarized membrane potential and characteristic late spiking firing pattern. The anatomical data revealed NGFC axons that covered a wide area of the middle and outer molecular layers, even extending into other brain areas such as subiculum and CA1 (similar to Ceranik et al., 1997), suggesting that these cells may have a role in coordinating activity of other cells within large sections of the dentate gyrus, and even between regions, providing direct GABAergic links between the dentate gyrus and the CA1 and subicular regions. Because of the heterogeneous nature of their synaptic partners, and because of their putative “volume transmission” in which any dendrite passing through the uniquely dense NGFC axonal cloud should receive NGFC input, we expect that NGFCs would be likely to synapse onto a variety of cell types with dendrites passing within their axonal clouds, both in the dentate molecular layer and in the CA1 and subicular regions. In addition, we confirmed the presence of several molecular markers of NGFCs in our recorded cells: NPY, COUP-TFII, nNOS, and reelin. We examined the output of molecular layer NGFCs to GCs and observed that the responses were mediated by both GABAA and GABAB currents, with the former being slower and smaller in amplitude but with charge transfer comparable to GABAA responses evoked by PVBCs. We noted that NGFCs receive low-frequency spontaneous events composed of both excitatory and inhibitory PSCs and that they receive input from the entorhinal cortex through the perforant path. Finally, we observed a number of types of electrical and chemical connectivity motifs between NGFCs and other molecular layer interneurons.

Identification of dentate NGFCs

The rigorous identification of interneuronal cell types requires that many factors be taken into account, including firing pattern, molecular markers, synaptic properties, and morphology. NGFCs present a particular challenge because few of these characteristics alone are definitive. NGFCs characteristically exhibit a late-spiking firing pattern, often with a ramp in membrane potential just before firing, a relatively fast time constant, and no sag. Although no sag is apparent in NGFCs of other brain areas of rats, human (Olah et al., 2007), and monkey (Povysheva et al., 2007), NGFCs do have a sag. Although firing pattern was useful in identifying candidate NGFCs for post hoc identification, it was insufficient to identify NGFCs positively. Thus, firing pattern was used only to select cells for further investigation.

Molecular markers are often helpful in confirming interneuronal cell types (for example, basket cells can be discretely segregated into PV+ and CCK+ subgroups, making such markers extremely useful for identification). As in other brain areas, we found that NGFCs in the dentate do express certain molecular markers, including NPY, nNOS, COUP TFII, and reelin [other known markers include α-actinin, GABAAα1, and GABAAδ (Deller and Leranth, 1990; Ratzliff and Soltesz, 2001; Price et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2005; Karagiannis et al., 2009; Olah et al., 2009; Fuentealba et al., 2010; Tricoire et al., 2010)]. However, no single one of these markers appears to be expressed by every NGFC, nor is any one of the markers specific to NGFCs alone (Nusser et al., 1995; Fuentealba et al., 2008; Karagiannis et al., 2009; Tricoire et al., 2010), making it difficult to identify NGFCs on an individual basis by using markers alone.

NGFC family cells have a unique ability to elicit a biphasic postsynaptic response consisting of both GABAA and GABAB currents with a single presynaptic action potential. Based on this synaptic property, a robust GABAB response to a single presynaptic action potential can be used to identify cells of the NGFC family positively. Indeed, we used this property on some (n = 2) occasions to identify NGFCs (see below). However, methods requiring paired recordings are generally impractical for identifying single NGFCs.

Filled NGFCs could be identified by recovering a sufficient portion of the axonal arbor to confirm the characteristic density and frequent boutons. Because this was the most straightforward confirmation available, all single-cell recordings of putative NGFCs were identified post hoc in this manner. Such morphological assessment requires high-quality filling, recovery, and DAB staining of these cells, making cell identification one difficult aspect of working with this cell type in the dentate. Investigators wishing to study dentate NGFCs can identify them post hoc primarily by their dense axons (multiple separate branches of axon crossing a single plane of focus) with frequent (2–3-µm interbouton interval) boutons and small (tens of micrometers from the cell body) dendritic arbors. Secondary characteristics that can be used to support the identification of NGFCs include a late-spiking firing pattern; molecular markers such as NPY, nNOS, COUP-TFII, reelin, GABAAα2, GABAAδ, and α-actinin; and slow GABAA and GABAB responses evoked by single presynaptic spikes.

Paired recordings of dentate NGFCs

The synaptic properties of NGFCs presented a second challenge to performing detailed studies. Because neurotransmission from NGFCs fatigues quickly in vitro with repeated stimulation (Tamas et al., 2003), cells for paired recordings were typically patched in a low-Ca2+ ACSF to prevent the release of vesicles from NGFCs until electrical control of the membrane potential could be achieved (see also Szabadics et al., 2007). Under conditions of low Ca2+, the firing patterns of cells are altered and are thus less reliable indicators of putative NGFCs for paired recordings. Additionally, wash-in of normal ACSF (10 minutes) was required before a connection could be tested, so paired recordings had to be extremely stable. Once a connection had been established, NGFCs were stimulated to fire an action potential only once every minute, again to prevent fatigue of the connection, limiting the data acquired for each pair. If, during paired recording, many action potentials were elicited in quick succession, the postsynaptic response gradually decreased in amplitude and recovered only after tens of minutes. Despite the challenges involved in rigorously identifying and making paired recordings from dentate NGFCs, we were able to record an ample number of both individual cells and pairs for analysis.

Relationship of NGFCs to “MOPP cells”

Existing information on molecular layer interneurons has included basket cells, axo-axonic cells, and even migrating developing interneurons, all with different axonal and dendritic morphologies (Ribak and Seress, 1983; Han et al., 1993; Freund and Buzsaki, 1996; Morozov et al., 2006; Amaral et al., 2007; Houser, 2007). However, reference to the MOPP (molecular layer perforant path associated) cell, a cell type first described by Han et al. and Halasy and Somogyi, both in 1993, whose axons and dendrites are located in the molecular layer, appears often in the literature. Descriptions of molecular layer cell morphologies have varied, including the cells that qualify as MOPP cells (Ribak and Seress, 1983; Seress and Ribak, 1983; Soriano and Frotscher, 1989, 1993; Halasy and Somogyi, 1993; Frotscher et al., 1994; Deller et al., 1996; Morozov et al., 2006; Amaral et al., 2007; Chittajallu et al., 2007). Indeed, NGFCs are molecular layer interneurons whose axons terminate in the same region as the perforant path, qualifying them as MOPP cells, and observations that some molecular layer interneurons share properties with certain stratum lacunosum-moleculare interneurons in CA1 (Khazipov et al., 1995; Nusser et al., 1995; Vida et al., 1998; Price et al., 2005), later determined to be NGFCs, suggest that at least some previously described MOPP cells might have included NGFCs. Additionally, previous reports of subiculumprojecting outer molecular layer interneurons (Ceranik et al., 1997) may in certain cases describe dentate NGFCs. However, non-NGFCs fitting the description of MOPP cells were also observed during this study, indicating that not all MOPP cells are NGFCs (Supp. Info. Fig. 1; Halasy and Somogyi, 1993). We suggest that the term MOPP cell be considered a broad category into which a number of specific interneuronal subpopulations in the molecular layer, including NGFCs, belong.

Additional reference has been made to GABAergic cells with cell bodies in and around the GC layer, extensive axonal arborization in the molecular layer. and innervation of granule cell dendrites (MOLAX cells; Soriano and Frotscher, 1993). In most cases, descriptions of MOLAX cells are not consistent with the NGFCs described in this study (Soriano and Frotscher, 1993; Frotscher et al., 1994; Deller et al., 1996).

Inputs to and feed-forward inhibitory role of dentate NGFCs

To understand how these cells work in the context of normal dentate circuitry, we wanted to gain some understanding of not only the targets of NGFC axons but also the nature of their inputs. Perforant path (PP) stimulation of NGFCs revealed that they do, indeed, receive input from entorhinal cortex, and paired recordings of NGFC to GC connections further revealed that these interneurons can perform feed-forward inhibition. The fact that PP inputs were facilitating at short (50 msec) but not longer ISIs suggests that NGFCs may be more involved in situations in which the rate of input to the dentate is increased, a property that could be important in regulating overall excitation or in coordinating timing among cell groups. However, more investigation will be required to determine how these cells respond to PP inputs in the intact entorhinal–hippocampal circuit in vivo. NGFC stimulation elicited both a slow GABAA as well as a late GABAB component in GCs, yielding a large inhibitory charge transfer with even a single action potential. Indeed, although the amplitude of PVBC-evoked events was more than six times greater than events evoked by NGFCs, the inhibitory charge transfer of the NGFC-evoked events was still comparable to that of PVBC-evoked events, underscoring the distinct and potentially important inhibitory role of the slow events evoked by NGFCs. The small size of the response to NGFCs measured at the soma of GCs may also be due in part to strong dendritic filtering owing to the cable properties of GC dendrites (Soltesz et al., 1995; Schmidt-Hieber et al., 2007), indicating that the response is likely more robust in the GC dendrite. The location of NGFC axons in the same dendritic compartment in which PP input also terminates suggests that these cells play a more important role in dendritic information processing than at the soma. Thus, NGFCs may help to establish or maintain the low excitability of GCs by interacting directly with sources of incoming excitation. Although the presence of GABAB currents in GCs in response to repeated PP stimulation has been observed (e.g., by Piguet, 1993), and GABAB receptors are prominent in dentate GCs (Kulik et al., 2003), future investigations into the dynamics of the PP→NGFC→GC pathway will likely require PP stimulation of connected NGFC–GC paired recordings as well as dendritic recordings from GCs in which the filtering of NGFC inputs would be minimized.

Spontaneous events in NGFCs were infrequent compared with those in GCs, a finding that is consistent with their smaller dendritic arbors. Among these spontaneous inputs, NGFCs receive similar sEPSC and sIPSC frequencies. Compared with NGFCs, GCs receive much more frequent sIPSCs. Our findings are consistent with the numerous local inhibitory inputs to GCs (Acsady et al., 1998; Buckmaster and Dudek, 1999). However, both NGFCs and GCs receive PP inputs in the intact brain. Therefore, further studies will be necessary to understand exactly how incoming PP excitation of NGFCs and GCs may interact with events originating locally.

Molecular layer microcircuits

Paired recordings between NGFCs and other molecular layer interneurons allowed us to make more specific observations about the local connectivity of NGFCs in this region. The two-cell motifs that we observed involving dentate NGFCs are particularly fascinating when considering what the role of these cells might be in the function of the dentate. Not only do NGFCs inhibit other inhibitory neurons with chemical synapses, but they have electrical connections to other types of inhibitory interneurons, sometimes even concurrently. The effect of having both electrical and chemical synaptic connections with other interneurons is not clear. Gap junctions may serve to excite or inhibit nearby neurons or may act as low-pass filters between cells and on incoming inputs (Mitchell and Silver, 2003; Zsiros et al., 2007). The diverse connectivity of these cells as demonstrated by the existence of all potential two-cell motifs might have a complex, major role in coordinating activity among molecular layer interneurons.

In the dentate, the NGFC represents a unique type of feed-forward inhibitory interneuron, receiving PP input and subsequently inhibiting granule cells with biphasic, slow inhibitory currents. Additionally, NGFCs have both gap junction connections and inhibitory chemical synapses with other molecular layer interneurons, both NGFCs and non-NGFCs. Because of the seemingly opposing roles of these two types of connections, NGFCs would be well suited for inclusion in future computational studies of the dentate (Santhakumar et al., 2005; Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen et al., 2007; Morgan and Soltesz, 2008; Ferrante et al., 2009) to help elucidate their functional significance. In addition to their unique connectivity, the extensive nature of NGFC axons within the molecular layer coupled with the postulated “volume transmission” from these axons (Olah et al., 2009; Capogna & Pearce, 2011) indicates that dentate NGFCs could broadly modulate the overall activity of the dentate and tune outputs of other interneuronal classes. These cells could also play important roles in pathological states. In addition, although the number of hilar interneurons is preferentially diminished in epilepsy and after head injury, molecular layer interneurons are not lost (Buckmaster and Jongen-Relo, 1999; Ratzliff and Soltesz, 2001), although some changes in properties have been noted (Peng et al., 2004). In the context of effects on GC excitability, both the loss of feedback inhibition from hilar interneurons and the continued inhibition of other interneurons by NGFCs could actually contribute to dentate gate breakdown in hyperexcitable states. Computational methods will prove invaluable for understanding what role NGFCs could play in dentate gyrus microcircuits under pathological conditions (Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen et al., 2007; Morgan and Soltesz, 2008). Dentate NGFCs are poised at the boundary between incoming cortical input and GC output, where their intrinsic and connective properties make them unique components of the microcircuitry modulating entorhinal–hippocampal interactions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rose Zhu and Dóra Hegedüs for expert technical assistance and general encouragement, Dr. Csaba Varga for advice on antibodies, and Dr. Stephen Ross for the generous loan of a Nikon FN-1 Eclipse microscope.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: NS35915; Grant sponsors: UC Irvine medical scientist training program (to C.A.); George E. Hewitt Foundation for Medical Research (to J.S.).

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

LITERATURE CITED

- Acsady L, Kamondi A, Sik A, Freund T, Buzsaki G. GABAergic cells are the major postsynaptic targets of mossy fibers in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3386–3403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Jonas P, Geiger JR. PTP and LTP at a hippocampal mossy fiber-interneuron synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14708–14713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251610898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Scharfman HE, Lavenex P. The dentate gyrus: fundamental neuroanatomical organization (dentate gyrus for dummies) Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:3–22. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitai Y, Gibson JR, Beierlein M, Patrick SL, Ho AM, Connors BW, Golomb D. The spatial dimensions of electrically coupled networks of interneurons in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4142–4152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-04142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Holmqvist B, Voorhoeve PE. Entorhinal activation of dentate granule cells. Acta Physiol Scand. 1966;66:448–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1966.tb03223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang CW, Carlson GC, Coulter DA. Massive and specific dysregulation of direct cortical input to the hippocampus in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11850–11856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2354-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr J, Lyson KJ, Mody I. Enhanced propagation of epileptiform activity through the kindled dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1726–1732. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Dudek FE. In vivo intracellular analysis of granule cell axon reorganization in epileptic rats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:712–721. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster PS, Jongen-Relo AL. Highly specific neuron loss preserves lateral inhibitory circuits in the dentate gyrus of kainate-induced epileptic rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9519–9529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09519.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Feed-forward inhibition in the hippocampal formation. Prog Neurobiol. 1984;22:131–153. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(84)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M. Neurogliaform cells and other interneurons of stratum lacunosum moleculare gate entorhinal-hippocampal dialogue. J Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Pearce RA. GABAA, slow: causes and consequences. Trends in Neurosciences. 2011;34(2):101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceranik K, Bender R, Geiger JR, Monyer H, Jonas P, Frotscher M, Lubke J. A novel type of GABAergic interneuron connecting the input and the output regions of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5380–5394. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05380.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittajallu R, Kunze A, Mangin JM, Gallo V. Differential synaptic integration of interneurons in the outer and inner molecular layers of the developing dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8219–8225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2476-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA. Chronic epileptogenic cellular alterations in the limbic system after status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999;40(Suppl 1):S23–S33. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00875.x. discussion S40-S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D, Lygate CA, Zhang MH, Hulbert K, Neubauer S, Casadei B. nNOS gene deletion exacerbates pathological left ventricular remodeling and functional deterioration after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:3729–3737. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bergeyck V, Nakajima K, Lambert de Rouvroit C, Naerhuyzen B, Goffinet AM, Miyata T, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K. A truncated Reelin protein is produced but not secreted in the “Orleans” reeler mutation (Reln[rl-Orl]) Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;50:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bergeyck V, Naerhuyzen B, Goffinet AM, Lambert de Rouvroit C. A panel of monoclonal antibodies against reelin, the extracellular matrix protein defective in reeler mutant mice. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;82:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T, Leranth C. Synaptic connections of neuropeptide Y (NPY) immunoreactive neurons in the hilar area of the rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;300:433–447. doi: 10.1002/cne.903000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deller T, Nitsch R, Frotscher M. Heterogeneity of the commissural projection to the rat dentate gyrus: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin tracing study. Neuroscience. 1996;75:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen J, Santhakumar V, Morgan RJ, Huerta R, Tsimring L, Soltesz I. Topological determinants of epileptogenesis in large-scale structural and functional models of the dentate gyrus derived from experimental data. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1566–1587. doi: 10.1152/jn.00950.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfant D, Pal BZ, Emptage N, Capogna M. Specific inhibitory synapses shift the balance from feedforward to feedback inhibition of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.06001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante M, Migliore M, Ascoli GA. Feed-forward inhibition as a buffer of the neuronal input–output relation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18004–18009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904784106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke RA, Prince DA. Electrophysiology of dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:195–209. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M, Soriano E, Misgeld U. Divergence of hippocampal mossy fibers. Synapse. 1994;16:148–160. doi: 10.1002/syn.890160208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Begum R, Capogna M, Jinno S, Marton LF, Csicsvari J, Thomson A, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Ivy cells: a population of nitric-oxide-producing, slow-spiking GABAergic neurons and their involvement in hippocampal network activity. Neuron. 2008;57:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Klausberger T, Karayannis T, Suen WY, Huck J, Tomioka R, Rockland K, Capogna M, Studer M, Morales M, Somogyi P. Expression of COUP-TFII nuclear receptor in restricted GABAergic neuronal populations in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1595–1609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4199-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasy K, Somogyi P. Subdivisions in the multiple GABAergic innervation of granule cells in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:411–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZS, Buhl EH, Lorinczi Z, Somogyi P. A high degree of spatial selectivity in the axonal and dendritic domains of physiologically identified local-circuit neurons in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:395–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Beck H, Dreier JP, Ficker E, Stabel J, Zhang CL. The dentate gyrus as a regulated gate for the propagation of epileptiform activity. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;7:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR. Interneurons of the dentate gyrus: an overview of cell types, terminal fields and neurochemical identity. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:217–232. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D. The dentate gyrus as a filter or gate: a look back and a look ahead. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:601–613. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis A, Gallopin T, David C, Battaglia D, Geoffroy H, Rossier J, Hillman EM, Staiger JF, Cauli B. Classification of NPY-expressing neocortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3642–3659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0058-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayannis T, Elfant D, Huera-Ocampo I, Teki S, Scott RS, Rusakov DA, Jones MV, Capogna M. Slow GABA transient and receptor desensitization shape synaptic responses evoked by hippocampal neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9898–9909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5883-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R, Congar P, Ben-Ari Y. Hippocampal CA1 lacunosum-moleculare interneurons: modulation of monosynaptic GABAergic IPSCs by presynaptic GABAB receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2126–2137. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Katsumaru H, Hama K, Wu JY, Heizmann CW. GABAergic neurons containing the Ca2+-binding protein parvalbumin in the rat hippocampus and dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 1987;419:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraushaar U, Jonas P. Efficacy and stability of quantal GABA release at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5594–5607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05594.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik A, Vida I, Lujan R, Haas CA, Lopez-Bendito G, Shigemoto R, Frotscher M. Subcellular localization of metabotropic GABAB receptor subunits GABAB1a/b and GABAB2 in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11026–11035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11026.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb JK, Leutgeb S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Pattern separation in the dentate gyrus and CA3 of the hippocampus. Science. 2007;315:961–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Stringer JL, Bertram EH. The dentate gyrus as a control point for seizures in the hippocampus and beyond. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;7:301–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AH, Katona I, Blatow M, Rozov A, Monyer H. In vivo labeling of parvalbumin-positive interneurons and analysis of electrical coupling in identified neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7055–7064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07055.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Silver RA. Shunting inhibition modulates neuronal gain during synaptic excitation. Neuron. 2003;38:433–445. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Kohr G, Otis TS, Staley KJ. The electrophysiology of dentate gyrus granule cells in whole-cell recordings. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992a;7:159–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Otis TS, Staley KJ, Kohr G. The balance between excitation and inhibition in dentate granule cells and its role in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992b;9:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RJ, Soltesz I. Nonrandom connectivity of the epileptic dentate gyrus predicts a major role for neuronal hubs in seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6179–6184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801372105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov YM, Ayoub AE, Rakic P. Translocation of synaptically connected interneurons across the dentate gyrus of the early postnatal rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5017–5027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0272-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser EI, Kropff E, Moser MB. Place cells, grid cells, and the brain’s spatial representation system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Mody I. Selective modulation of tonic and phasic inhibitions in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2624–2628. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Baude A, Richards JG, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. Immunocytochemical localization of the alpha 1 and beta 2/3 subunits of the GABAA receptor in relation to specific GABAergic synapses in the dentate yrus. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:630–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah S, Komlosi G, Szabadics J, Varga C, Toth E, Barzo P, Tamas G. Output of neurogliaform cells to various neuron types in the human and rat cerebral cortex. Front Neural Circuits. 2007;1:4. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.004.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah S, Fule M, Komlosi G, Varga C, Baldi R, Barzo P, Tamas G. Regulation of cortical microcircuits by unitary GABA-mediated volume transmission. Nature. 2009;461:1278–1281. doi: 10.1038/nature08503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak HR, Weissinger F, Terunuma M, Carlson GC, Hsu FC, Moss SJ, Coulter DA. Disrupted dentate granule cell chloride regulation enhances synaptic excitability during development of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14012–14022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Huang CS, Stell BM, Mody I, Houser CR. Altered expression of the delta subunit of the GABAA receptor in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8629–8639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttonen M, Kamondi A, Sik A, Acsady L, Buzsaki G. Feed-forward and feed-back activation of the dentate gyrus in vivo during dentate spikes and sharp wave bursts. Hippocampus. 1997;7:437–450. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:4<437::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, Uzunov DP, Costa E, Guidotti A, Caruncho HJ. Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3221–3226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet P. GABAA- and GABAB-mediated inhibition in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Epilepsy Res. 1993;16:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(93)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povysheva NV, Zaitsev AV, Kroner S, Krimer OA, Rotaru DC, Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA, Krimer LS. Electrophysiological differences between neurogliaform cells from monkey and rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1030–1039. doi: 10.1152/jn.00794.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Cauli B, Kovacs ER, Kulik A, Lambolez B, Shigemoto R, Capogna M. Neurogliaform neurons form a novel inhibitory network in the hippocampal CA1 area. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6775–6786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Scott R, Rusakov DA, Capogna M. GABAB receptor modulation of feedforward inhibition through hippocampal neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6974–6982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4673-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Suh JM, Kim BJ, Yu CT, Tanaka T, Kodama T, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. The expression pattern of nuclear receptors during cerebellar development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:810–820. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y, Cajal S. Texture of the nervous system of man and the vertebrates. Barcelona: Spring-Verlag/Wein: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzliff AD, Soltesz I. Differential immunoreactivity for alpha-actinin-2, an N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor/actin binding protein, in hippocampal interneurons. Neuroscience. 2001;103:337–349. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribak CE, Seress L. Five types of basket cell in the hippocampal dentate gyrus: a combined Golgi and electron microscopic study. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:577–597. doi: 10.1007/BF01181525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhakumar V, Aradi I, Soltesz I. Role of mossy fiber sprouting and mossy cell loss in hyperexcitability: a network model of the dentate gyrus incorporating cell types and axonal topography. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:437–453. doi: 10.1152/jn.00777.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE. Differentiation of rat dentate neurons by morphology and electrophysiology in hippocampal slices: granule cells, spiny hilar cells and aspiny “fast-spiking” cells. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;7:93–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Subthres-hold dendritic signal processing and coincidence detection in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8430–8441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1787-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller B, Dick J, Dhoot G, Carroll S, Vrbova G, Nicotera P, Pette D, Wyss A, Bluethmann H, Hunziker W, Celio MR. Prolonged contraction–relaxation cycle of fast-twitch muscles in parvalbumin knockout mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C395–C403. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.2.C395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seress L, Ribak CE. GABAergic cells in the dentategyrus appear to be local circuit and projection neurons. Exp Brain Res. 1983;50:173–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00239181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seress L, Ribak CE. Direct commissural connections to the basket cells of the hippocampal dentate gyrus: anatomical evidence for feed-forward inhibition. J Neurocytol. 1984;13:215–225. doi: 10.1007/BF01148116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A, Olah S, Molnar G, Szabadics J, Tamas G. Gap-junctional coupling between neurogliaform cells and various interneuron types in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6278–6285. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1431-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS. Feedforward and feedback inhibition of hippocampal principal cell activity evoked by perforant path stimulation: GABA-mediated mechanisms that regulate excitability in vivo. Hippocampus. 1991;1:31–40. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS, Brisman JL. Lateral inhibition and granule cell synchrony in the rat hippocampal dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:811–820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00811.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I, Smetters DK, Mody I. Tonic inhibition originates from synapses close to the soma. Neuron. 1995;14:1273–1283. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano E, Frotscher M. A GABAergic axo-axonic cell in the fascia dentata controls the main excitatory hippocampal pathway. Brain Res. 1989;503:170–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano E, Frotscher M. GABAergic innervation of the rat fascia dentata: a novel type of interneuron in the granule cell layer with extensive axonal arborization in the molecular layer. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334:385–396. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Otis TS, Mody I. Membrane properties of dentate gyrus granule cells: comparison of sharp microelectrode and whole-cell recordings. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1346–1358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ste. Marie L, Luquet S, Cole TB, Palmiter RD. Modulation of neuropeptide Y expression in adult mice does not affect feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18632–18637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O. Topographic organization of the projections from the entorhinal area to the hippocampal formation of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1976;167:285–314. doi: 10.1002/cne.901670303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics J, Soltesz I. Functional specificity of mossy fiber innervation of GABAergic cells in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4239–4251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5390-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics J, Tamas G, Soltesz I. Different transmitter transients underlie presynaptic cell type specificity of GABAA,slow and GABAA,fast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14831–14836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]